Aldose: Difference between revisions

→Stereochemistry: More rewording for clarity. Not a stub anymore. |

Tom.Reding (talk | contribs) m +{{Authority control}} (1 ID from Wikidata); WP:GenFixes & cleanup on |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Class of monosaccharides}} |

|||

An '''aldose''' is a [[monosaccharide]] (a simple sugar) with a carbon backbone chain with a [[carbonyl group]] on the endmost carbon atom, making it an [[aldehyde]], and [[Hydroxy group|hydroxyl groups]] connected to all the other carbon atoms. Aldoses can be distinguished from [[ |

An '''aldose''' is a [[monosaccharide]] (a simple sugar) with a carbon backbone chain with a [[carbonyl group]] on the endmost carbon atom, making it an [[aldehyde]], and [[Hydroxy group|hydroxyl groups]] connected to all the other carbon atoms. Aldoses can be distinguished from [[ketose]]s, which have the carbonyl group away from the end of the molecule, and are therefore [[ketone]]s. |

||

==Structure== |

==Structure== |

||

[[File:D-Glyceraldehyde 2D Fischer.svg|thumb|140px|[[Fischer projection]] of {{ |

[[File:D-Glyceraldehyde 2D Fischer.svg|thumb|140px|[[Fischer projection]] of {{sc|D}}-[[glyceraldehyde]]]] |

||

Like most carbohydrates, simple aldoses have the general [[chemical formula]] C<sub>''n''</sub>(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>''n''</sub>. Because [[formaldehyde]] (n=1) and [[glycolaldehyde]] (n=2) are not generally considered to be carbohydrates,<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |

Like most carbohydrates, simple aldoses have the general [[chemical formula]] C<sub>''n''</sub>(H<sub>2</sub>O)<sub>''n''</sub>. Because [[formaldehyde]] (n=1) and [[glycolaldehyde]] (n=2) are not generally considered to be carbohydrates,<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Biochemistry|last=Mathews|first=Christopher K.|date=2000|publisher=Benjamin Cummings|others=Van Holde, K. E. (Kensal Edward), 1928-, Ahern, Kevin G.|isbn=0805330666|edition=3rd|location=San Francisco, Calif.|pages=280–293|oclc=42290721}}</ref> the simplest possible aldose is the [[triose]] [[glyceraldehyde]], which only contains three [[carbon]] [[atom]]s.<ref>{{cite book| last=Berg| first=J.M.| edition=6th| title=Biochemistry| year=2006| publisher=W. H. Freeman and Company| location=New York}}</ref> |

||

Because they have at least one asymmetric |

Because they have at least one asymmetric carbon center, all aldoses exhibit [[stereoisomerism]]. Aldoses can exist in either a {{sc|D}}- form or {{sc|L}}- form. The determination is made based on the chirality of the asymmetric carbon furthest from the aldehyde end, namely the second-last carbon in the chain. Aldoses with alcohol groups on the right of the [[Fischer projection]] are {{sc|D}}-aldoses, and those with alcohols on the left are {{sc|L}}-aldoses. {{sc|D}}-aldoses are more common than {{sc|L}}-aldoses in nature.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

Examples of aldoses include [[glyceraldehyde]], [[erythrose]], [[ribose]], [[glucose]] and [[galactose]]. |

Examples of aldoses include [[glyceraldehyde]], [[erythrose]], [[ribose]], [[glucose]] and [[galactose]]. Ketoses and aldoses can be chemically differentiated through [[Seliwanoff's test]], where the sample is heated with acid and [[resorcinol]].<ref>{{cite web| title=Seliwanoff's Test| publisher=Harper College| access-date=2011-07-10| url=http://www.harpercollege.edu/tm-ps/chm/100/dgodambe/thedisk/carbo/seli/seli.htm| archive-date=2017-12-16| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171216032307/http://www.harpercollege.edu/tm-ps/chm/100/dgodambe/thedisk/carbo/seli/seli.htm| url-status=dead}}</ref> The test relies on the [[dehydration reaction]] which occurs more quickly in ketoses, so that while aldoses react slowly, producing a light pink color, ketoses react more quickly and strongly to produce a dark red color. |

||

Aldoses can [[isomer]]ize to ketoses through the [[Lobry-de Bruyn-van Ekenstein transformation]]. |

Aldoses can [[isomer]]ize to ketoses through the [[Lobry-de Bruyn-van Ekenstein transformation]]. |

||

==Nomenclature and common aldoses== |

==Nomenclature and common aldoses== |

||

[[File:Family tree aldoses.svg|thumbnail|400px|Family tree of aldoses: (1) {{ |

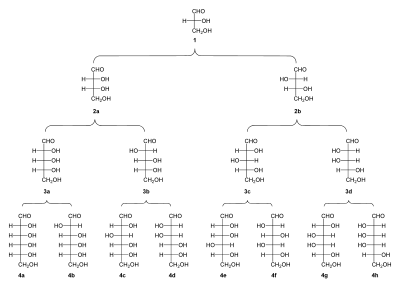

[[File:Family tree aldoses.svg|thumbnail|400px|Family tree of aldoses: (1) {{sc|D}}-(+)-glyceraldehyde; (2a) {{sc|D}}-(−)-erythrose; (2b) {{sc|D}}-(−)-threose; (3a) {{sc|D}}-(−)-ribose; (3b) {{sc|D}}-(−)-arabinose; (3c) {{sc|D}}-(+)-xylose; (3d) {{sc|D}}-(−)-lyxose; (4a) {{sc|D}}-(+)-allose; (4b) {{sc|D}}-(+)-altrose; (4c) {{sc|D}}-(+)-glucose; (4d) {{sc|D}}-(+)-mannose; (4e) {{sc|D}}-(−)-gulose; (4f) {{sc|D}}-(−)-idose; (4g) {{sc|D}}-(+)-galactose; (4h) {{sc|D}}-(+)-talose]]Aldoses are differentiated by the number of carbon atoms in the main chain. The minimum number of carbon atoms in a backbone needed to form a molecule that is still considered a carbohydrate is 3, and carbohydrates with three carbon atoms are called trioses. The only aldotriose is [[glyceraldehyde]], which has one chiral stereocenter with 2 possible enantiomers, {{sc|D}}- and {{sc|L}}-glyceraldehyde. |

||

Some common aldoses are: |

Some common aldoses are: |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

*[[Tetrose]]s: [[erythrose]], [[threose]] |

*[[Tetrose]]s: [[erythrose]], [[threose]] |

||

*[[Pentose]]s: [[ribose]], [[arabinose]], [[xylose]], [[lyxose]] |

*[[Pentose]]s: [[ribose]], [[arabinose]], [[xylose]], [[lyxose]] |

||

*[[Hexose |

*[[Hexose]]s: [[glucose]] |

||

The most commonly discussed category of aldoses are those with |

The most commonly discussed category of aldoses are those with six carbon atoms, [[aldohexose]]s. Some aldohexoses that are widely called by common names are:<ref>{{Cite book|title=Organic Chemistry|last=Solomons|first=T.W. Graham|publisher=John Wiley & Sons Inc.|year=2008|pages=1044}}</ref> |

||

* D-(+)-[[Allose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Allose]] |

||

* D-(+)-[[Altrose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Altrose]] |

||

* D-(+)-[[Glucose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Glucose]] |

||

* D-(+)-[[Mannose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Mannose]] |

||

* D-( |

* {{sc|D}}-(−)-[[Gulose]] |

||

* D-(+)-[[Idose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Idose]] |

||

* D-(+)-[[Galactose]] |

* {{sc|D}}-(+)-[[Galactose]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== Stereochemistry == |

== Stereochemistry == |

||

Aldoses are commonly referred to by names specific to one stereoisomer of the compound. This distinction is especially vital in |

Aldoses are commonly referred to by names specific to one stereoisomer of the compound. This distinction is especially vital in biochemistry, as many systems can only use one enantiomer of the carbohydrate and not the other. However, aldoses are not locked into any one conformation: they can and do fluctuate between different forms. |

||

Aldoses can [[ |

Aldoses can [[tautomer]]ize to ketoses in a dynamic process with an [[enol]] intermediate (more specifically, an enediol).<ref name=":0" /> This process is reversible, so aldoses and ketoses can be thought of as being in equilibrium with each other. However, aldehydes and ketones are almost always more stable than the corresponding enol forms, so the aldo- and keto- forms normally predominate. This process, with its enol intermediate, also allows stereoisomerization. Basic solutions accelerate the interconversion of isomers. |

||

Carbohydrates with more than |

Carbohydrates with more than four carbon atoms exist in an equilibrium between the closed ring, or cyclic form, and the open-chain form. Cyclic aldoses are usually drawn as [[Haworth projection]]s, and open chain forms are commonly drawn as [[Fischer projection]]s, both of which represent important stereochemical information about the forms they depict.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

{{Carbohydrates}} |

{{Carbohydrates}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Aldoses| ]] |

[[Category:Aldoses| ]] |

||

[[Category:Aldols]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 16:35, 22 October 2023

An aldose is a monosaccharide (a simple sugar) with a carbon backbone chain with a carbonyl group on the endmost carbon atom, making it an aldehyde, and hydroxyl groups connected to all the other carbon atoms. Aldoses can be distinguished from ketoses, which have the carbonyl group away from the end of the molecule, and are therefore ketones.

Structure

[edit]

Like most carbohydrates, simple aldoses have the general chemical formula Cn(H2O)n. Because formaldehyde (n=1) and glycolaldehyde (n=2) are not generally considered to be carbohydrates,[1] the simplest possible aldose is the triose glyceraldehyde, which only contains three carbon atoms.[2]

Because they have at least one asymmetric carbon center, all aldoses exhibit stereoisomerism. Aldoses can exist in either a D- form or L- form. The determination is made based on the chirality of the asymmetric carbon furthest from the aldehyde end, namely the second-last carbon in the chain. Aldoses with alcohol groups on the right of the Fischer projection are D-aldoses, and those with alcohols on the left are L-aldoses. D-aldoses are more common than L-aldoses in nature.[1]

Examples of aldoses include glyceraldehyde, erythrose, ribose, glucose and galactose. Ketoses and aldoses can be chemically differentiated through Seliwanoff's test, where the sample is heated with acid and resorcinol.[3] The test relies on the dehydration reaction which occurs more quickly in ketoses, so that while aldoses react slowly, producing a light pink color, ketoses react more quickly and strongly to produce a dark red color.

Aldoses can isomerize to ketoses through the Lobry-de Bruyn-van Ekenstein transformation.

Nomenclature and common aldoses

[edit]

Aldoses are differentiated by the number of carbon atoms in the main chain. The minimum number of carbon atoms in a backbone needed to form a molecule that is still considered a carbohydrate is 3, and carbohydrates with three carbon atoms are called trioses. The only aldotriose is glyceraldehyde, which has one chiral stereocenter with 2 possible enantiomers, D- and L-glyceraldehyde.

Some common aldoses are:

- Triose: glyceraldehyde

- Tetroses: erythrose, threose

- Pentoses: ribose, arabinose, xylose, lyxose

- Hexoses: glucose

The most commonly discussed category of aldoses are those with six carbon atoms, aldohexoses. Some aldohexoses that are widely called by common names are:[4]

- D-(+)-Allose

- D-(+)-Altrose

- D-(+)-Glucose

- D-(+)-Mannose

- D-(−)-Gulose

- D-(+)-Idose

- D-(+)-Galactose

- D-(+)-Talose

Stereochemistry

[edit]Aldoses are commonly referred to by names specific to one stereoisomer of the compound. This distinction is especially vital in biochemistry, as many systems can only use one enantiomer of the carbohydrate and not the other. However, aldoses are not locked into any one conformation: they can and do fluctuate between different forms.

Aldoses can tautomerize to ketoses in a dynamic process with an enol intermediate (more specifically, an enediol).[1] This process is reversible, so aldoses and ketoses can be thought of as being in equilibrium with each other. However, aldehydes and ketones are almost always more stable than the corresponding enol forms, so the aldo- and keto- forms normally predominate. This process, with its enol intermediate, also allows stereoisomerization. Basic solutions accelerate the interconversion of isomers.

Carbohydrates with more than four carbon atoms exist in an equilibrium between the closed ring, or cyclic form, and the open-chain form. Cyclic aldoses are usually drawn as Haworth projections, and open chain forms are commonly drawn as Fischer projections, both of which represent important stereochemical information about the forms they depict.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mathews, Christopher K. (2000). Biochemistry. Van Holde, K. E. (Kensal Edward), 1928-, Ahern, Kevin G. (3rd ed.). San Francisco, Calif.: Benjamin Cummings. pp. 280–293. ISBN 0805330666. OCLC 42290721.

- ^ Berg, J.M. (2006). Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

- ^ "Seliwanoff's Test". Harper College. Archived from the original on 2017-12-16. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ^ Solomons, T.W. Graham (2008). Organic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons Inc. p. 1044.