Portland Rum Riot: Difference between revisions

Iridescent (talk | contribs) m →History: Typo fixing, typo(s) fixed: May of 1855 → May 1855 using AWB |

removed Category:Irish-American culture in Maine; added Category:Irish-American culture in Portland, Maine using HotCat |

||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{more footnotes|date=June 2013}} |

|||

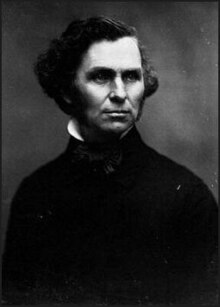

[[File:NSDow2.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Mayor Neal Dow]] |

[[File:NSDow2.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Mayor Neal Dow]] |

||

[[File:Old Portland City Hall.jpg|thumb|Portland's City Hall, site of the rum riot]] |

[[File:Old Portland City Hall.jpg|thumb|Portland's City Hall, site of the rum riot, in 1886]] |

||

The '''Portland Rum Riot''', also called the '''Maine Law Riot''', was a brief but violent period of civil unrest that occurred in [[Portland, Maine]] on June 2, 1855, in response to the [[Maine law]] which prohibited the sale and manufacture of [[alcohol]] in the state from 1851. |

The '''Portland Rum Riot''', also called the '''Maine Law Riot''', and the '''June Riot''' by [[Neal Dow]], was a brief but violent period of civil unrest that occurred in [[Portland, Maine]] on June 2, 1855, in response to the [[Maine law]] which prohibited the sale and manufacture of [[alcohol (drug)|alcohol]] in the state from 1851.<ref name="Danver2011">{{cite book |last1=Danver |first1=Steven L. |title=Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia |date=2011 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |location=Santa Barbara, Calif. |isbn=978-1-59884-222-7 |pages=365–367 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eSncBZ9E14UC |language=en}}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The [[Maine law]] of 1851 outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state of Maine, except for medicinal and mechanical purposes. In May 1855, rumors began to spread that Portland Mayor [[Neal Dow]] |

The [[Maine law]] of 1851 outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state of Maine, except for medicinal and mechanical purposes. In May 1855, rumors began to spread that Portland Mayor [[Neal Dow]], an outspoken [[prohibition|prohibitionist]] also known as the "Napoleon of Temperance", was keeping a large supply of alcohol in the city. As mayor, Dow had authorized a shipment of $1,600 worth of "medicinal and mechanical alcohol" that was being stored in the city vaults for distribution to [[pharmacists]] and [[physician|doctors]] (as was authorized under the Maine law), but this detail was not widely reported. To further complicate matters, Dow and the city alderman<!--aldermen?--> began a vocal battle over the shipment because they had not authorized the expenditure.<ref>Portland (Me.) Advertiser, June 5, 1855, p. 2.</ref> |

||

Portland’s large [[Irish Americans|Irish immigrant]] population were particularly vocal critics of the Maine Law, seeing it as thinly veiled racist attack on their culture. They already disliked and distrusted Dow, and this incident made him appear to be a [[hypocrite]]. The Maine law that Dow had sponsored had a mechanism whereby any three voters could apply for a search warrant if they suspected someone was selling liquor illegally. Three men did appear before a judge, who was compelled to issue a search warrant. |

Portland’s large [[Irish Americans|Irish immigrant]] population were particularly vocal critics of the Maine Law, seeing it as thinly veiled racist attack on their culture. They already disliked and distrusted Dow, and this incident made him appear to be a [[hypocrite]].{{cn|date=October 2023}} The Maine law that Dow had sponsored had a mechanism whereby any three voters could apply for a search warrant if they suspected someone was selling liquor illegally. Three men did appear before a judge, who was compelled to issue a search warrant.<ref name="Danver2011"/> |

||

On the afternoon of June 2, a crowd began to gather outside the building where the spirits were being held. The crowd numbered about 200 by 5:00 p.m. and grew larger and more agitated as the day progressed as it became evident that the police had no immediate plans to seize or destroy the liquor. Separate contemporary accounts place the [[crowd size estimation|crowd's size]] between 1,000 and 3,000 by evening (out of a city population of about 21,000). As the crowd became larger, rock throwing and shoving began. |

On the afternoon of June 2, a crowd began to gather outside the building where the spirits were being held. The crowd numbered about 200 by 5:00 p.m. and grew larger and more agitated as the day progressed as it became evident that the police had no immediate plans to seize or destroy the liquor. Separate contemporary accounts place the [[crowd size estimation|crowd's size]] between 1,000 and 3,000 by evening (out of a city population of about 21,000). As the crowd became larger, rock throwing and shoving began.<ref name="Danver2011"/> |

||

Police were unable to deal with the growing mob, and Dow called out the [[militia]]. The exact details of the climax of the riot have been hotly debated. What is known is that after ordering the protesters to disperse, the militia detachment fired into the crowd on Dow's orders. One man, John Robbins, an immigrant and mate of a Maine sailing vessel from [[Deer Isle, Maine|Deer Isle]], was killed, and seven others were wounded.{{Citation needed|date = March 2017}} |

Police were unable to deal with the growing mob, and Dow called out the [[militia]]. The exact details of the climax of the riot have been hotly debated. What is known is that after ordering the protesters to disperse, the militia detachment fired into the crowd on Dow's orders. One man, John Robbins, an immigrant and mate of a Maine sailing vessel from [[Deer Isle, Maine|Deer Isle]], was killed, and seven others were wounded.{{Citation needed|date = March 2017}} |

||

The crowd was dispersed, but Dow was widely criticized for his heavy-handed tactics during the incident. |

The crowd was dispersed, but Dow was widely criticized for his heavy-handed tactics during the incident.<ref name="Danver2011"/> |

||

In a twist of irony, Dow was later prosecuted for violation of the Maine Law for improperly acquiring the alcohol. The prosecutor was former U.S. Attorney General [[Nathan Clifford]], and the defense attorney was later U.S. Senator and Secretary of the Treasury [[William P. Fessenden]]. Dow was acquitted, but the event was a major contributing factor to the repeal of the Maine law in 1856. |

In a twist of irony, Dow was later prosecuted for violation of the Maine Law for improperly acquiring the alcohol. The prosecutor was former U.S. Attorney General [[Nathan Clifford]], and the defense attorney was later U.S. Senator and Secretary of the Treasury [[William P. Fessenden]]. Fessenden was also a member of the Maine Temperance Union. Dow was acquitted, but the event was a major contributing factor to the repeal of the Maine law in 1856.<ref name="Danver2011"/> |

||

==Commemorations== |

==Commemorations== |

||

| Line 24: | Line 23: | ||

* {{cite book |last=Rolde |first=Neal |title=Maine: A Narrative History |year=1990 |publisher=Harpswell Press |location=Gardiner, ME |isbn=0-88448-069-0 |page=178 }} |

* {{cite book |last=Rolde |first=Neal |title=Maine: A Narrative History |year=1990 |publisher=Harpswell Press |location=Gardiner, ME |isbn=0-88448-069-0 |page=178 }} |

||

* {{cite news|last1=Bouchard|first1=Kelley|title=When Maine went dry|url=http://www.pressherald.com/2011/10/02/when-maine-went-dry_2011-10-02/|accessdate=4 January 2016|publisher=Portland Press Herald|date=2 October 2011}} |

* {{cite news|last1=Bouchard|first1=Kelley|title=When Maine went dry|url=http://www.pressherald.com/2011/10/02/when-maine-went-dry_2011-10-02/|accessdate=4 January 2016|publisher=Portland Press Herald|date=2 October 2011}} |

||

{{Riots in the United States (1607–1865)}} |

|||

[[Category:1855 in Maine]] |

[[Category:1855 in Maine]] |

||

[[Category:19th century in Portland, Maine]] |

[[Category:19th century in Portland, Maine]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Discrimination in Maine]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Irish-American culture in Portland, Maine]] |

||

[[Category:Temperance movement in Maine]] |

|||

[[Category:1855 riots]] |

[[Category:1855 riots]] |

||

[[Category:Riots and civil disorder in Maine]] |

[[Category:Riots and civil disorder in Maine]] |

||

[[Category:June 1855 events]] |

[[Category:June 1855 events]] |

||

[[Category:Neal Dow]] |

|||

[[Category:Political riots in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:19th-century political riots]] |

|||

[[Category:1850s political events]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 15:39, 22 January 2024

The Portland Rum Riot, also called the Maine Law Riot, and the June Riot by Neal Dow, was a brief but violent period of civil unrest that occurred in Portland, Maine on June 2, 1855, in response to the Maine law which prohibited the sale and manufacture of alcohol in the state from 1851.[1]

History

[edit]The Maine law of 1851 outlawed the manufacture and sale of alcohol in the state of Maine, except for medicinal and mechanical purposes. In May 1855, rumors began to spread that Portland Mayor Neal Dow, an outspoken prohibitionist also known as the "Napoleon of Temperance", was keeping a large supply of alcohol in the city. As mayor, Dow had authorized a shipment of $1,600 worth of "medicinal and mechanical alcohol" that was being stored in the city vaults for distribution to pharmacists and doctors (as was authorized under the Maine law), but this detail was not widely reported. To further complicate matters, Dow and the city alderman began a vocal battle over the shipment because they had not authorized the expenditure.[2]

Portland’s large Irish immigrant population were particularly vocal critics of the Maine Law, seeing it as thinly veiled racist attack on their culture. They already disliked and distrusted Dow, and this incident made him appear to be a hypocrite.[citation needed] The Maine law that Dow had sponsored had a mechanism whereby any three voters could apply for a search warrant if they suspected someone was selling liquor illegally. Three men did appear before a judge, who was compelled to issue a search warrant.[1]

On the afternoon of June 2, a crowd began to gather outside the building where the spirits were being held. The crowd numbered about 200 by 5:00 p.m. and grew larger and more agitated as the day progressed as it became evident that the police had no immediate plans to seize or destroy the liquor. Separate contemporary accounts place the crowd's size between 1,000 and 3,000 by evening (out of a city population of about 21,000). As the crowd became larger, rock throwing and shoving began.[1]

Police were unable to deal with the growing mob, and Dow called out the militia. The exact details of the climax of the riot have been hotly debated. What is known is that after ordering the protesters to disperse, the militia detachment fired into the crowd on Dow's orders. One man, John Robbins, an immigrant and mate of a Maine sailing vessel from Deer Isle, was killed, and seven others were wounded.[citation needed]

The crowd was dispersed, but Dow was widely criticized for his heavy-handed tactics during the incident.[1]

In a twist of irony, Dow was later prosecuted for violation of the Maine Law for improperly acquiring the alcohol. The prosecutor was former U.S. Attorney General Nathan Clifford, and the defense attorney was later U.S. Senator and Secretary of the Treasury William P. Fessenden. Fessenden was also a member of the Maine Temperance Union. Dow was acquitted, but the event was a major contributing factor to the repeal of the Maine law in 1856.[1]

Commemorations

[edit]The 160th anniversary of the Rum Riot was observed in a 2015 ceremony. The ceremony was held indoors because of rain.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Danver, Steven L. (2011). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 365–367. ISBN 978-1-59884-222-7.

- ^ Portland (Me.) Advertiser, June 5, 1855, p. 2.

- ^ Bouchard, Kelley (1 June 2015). "Commemoration of Portland Rum Riot moved indoors to City Hall". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Rolde, Neal (1990). Maine: A Narrative History. Gardiner, ME: Harpswell Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-88448-069-0.

- Bouchard, Kelley (2 October 2011). "When Maine went dry". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved 4 January 2016.