Euryapsida: Difference between revisions

The group known as "Euryapsids" is not a true taxaomic group. They DO NOT include Placodonts or Plesiosaurs which are members of the wider taxonomic group "Sauropterygia". Please see Storrs 1993, Motani 2009, etc for confirmation of this. |

+ {{Sauropsida}} |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

__NOTOC__ |

|||

{{NOTOC}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{refimprove|date=July 2011}} |

|||

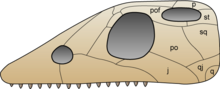

'''Euryapsida''' is a [[polyphyletic]] (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of [[Sauropsida|sauropsids]] that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the [[orbit (anatomy)|orbit]], under which the post-orbital and squamosal bones articulate. They are different from [[Synapsida]], which also have a single opening behind the orbit, by the placement of the fenestra. In synapsids, this opening is below the articulation of the post-orbital and squamosal bones. It is now commonly believed that euryapsids (particularly [[sauropterygia]]ns) are in fact [[diapsid]]s (which have two fenestrae behind the orbit) that lost the lower temporal fenestra. Euryapsids are usually considered entirely extinct, although [[turtle]]s might be part of the sauropterygian clade<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lee |first=M. S. Y. |date=2013 |title=Turtle origins: insights from phylogenetic retrofitting and molecular scaffolds |journal=Journal of Evolutionary Biology |language=en |volume=26 |issue=12 |pages=2729–2738 |doi=10.1111/jeb.12268|doi-access=free |pmid=24256520 }}</ref> while other authors disagree.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last1=Simões |first1=Tiago R. |last2=Kammerer |first2=Christian F. |last3=Caldwell |first3=Michael W. |last4=Pierce |first4=Stephanie E. |date=2022-08-19 |title=Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles |journal=Science Advances |language=en |volume=8 |issue=33 |pages=eabq1898 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.abq1898 |issn=2375-2548 |pmc=9390993 |pmid=35984885|bibcode=2022SciA....8.1898S }}</ref> Euryapsida may also be a synonym of Sauropterygia ''sensu lato''.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Rieppel |first=Olivier |date=1989-01-04 |title=A new pachypleurosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio, Switzerland |url=https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.1989.0001 |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences |language=en |volume=323 |issue=1212 |pages=1–73 |doi=10.1098/rstb.1989.0001 |issn=0080-4622}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

'''Euryapsida''' is a [[polyphyletic]] (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of [[reptile]]s that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the [[orbit (anatomy)|orbit]], under which the post-orbital and squamosal bones articulate. They are different from [[Synapsida]], which also have a single opening behind the orbit, by the placement of the fenestra. In synapsids, this opening is below the articulation of the post-orbital and squamosal bones. It is now commonly believed that euryapsids are in fact [[diapsid]]s (which have two fenestrae behind the orbit) that lost the lower temporal fenestra. There are no surviving descendants of the euryapsids. |

|||

The [[ichthyosaur]]ian skull is sometimes described as having a ''metapsid'' (or ''parapsid'') condition instead of a truly euryapsid one. In ichthyosaurs, the squamosal bone is never part of the fenestra's margin.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Maisch |first=M. |date=2010 |title=Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art |journal=Palaeodiversity |volume=3 |pages=151–214|s2cid=87979321 |language=en}}</ref> Parapsida was originally a taxon consisting of ichthyosaurs, squamates, protorosaurs, araeoscelidans and [[Pleurosauridae|pleurosaurs]].<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

The term Enaliosauria was once used for ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs combined as well.<ref>http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/enaliosauria</ref> |

|||

Historically, a variety of reptiles with upper fenestrae, either alone or with a lower emargination, have been considered euryapsid or parapsid, and to have had their patterns of fenestration originate separately from those of diapsids. This includes [[araeoscelida]]ns, [[mesosaur]]s, [[squamate]]s, [[pleurosaurid]]s,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Williston |first=Samuel Wendell |title=Osteology of the Reptiles |year=1925}}</ref> [[weigeltisaurid]]s, [[protorosaur]]s, and [[trilophosaur]]s.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Romer |first=Alfred Sherwood |title=Osteology of the Reptiles |year=1956}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Romer |first=Alfred Sherwood |title=Vertebrate Paleontology |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=1966 |edition=3rd |location=Chicago |language=en}}</ref> With the exception of mesosaurs, which only have the lower temporal opening, all of these are universally agreed to be diapsids which either secondarily closed the lower opening (araeoscelids, trilophosaurs) or lost the lower bar (squamates, pleurosaurs, protorosaurs). |

|||

[[Image:Ichthyosaur Drawing.jpg|thumb|[[Ichthyosaur]]]] |

|||

Examples are: |

|||

*[[Ichthyosaur]]s |

|||

Euryapsida was proposed by [[Edwin H. Colbert]] as a substitute for the earlier term '''Synaptosauria''', originally created by [[Edward Drinker Cope|Edward D. Cope]] for a taxon including sauropterygians, turtles and rhynchocephalians. [[Georg Baur|Baur]] removed the rhynchocephalians from Synaptosauria and [[Samuel Wendell Williston|Williston]] later resurrected the taxon, including only Sauropterygia ([[Nothosaur]]ia and [[Plesiosaur]]ia) and [[Placodontia]] in it.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

The group no longer contains: |

|||

*[[Sauropteryia]]ns |

|||

[[Image:Skull parapsida 1.png|thumb|right|A parapsid skull.]] |

|||

The terms '''Enaliosauria''' and '''Halisauria''' have also been used for a taxon including ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Enaliosauria|title=Enaliosauria|dictionary=Merriam-Webster|access-date=22 December 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Haeckel |first=Ernst |title=Die systematische Phylogenie (Dritter Theil/Systematische Phylogenie der Wirbelthiere (Vertebrata)) |publisher=Georg Reimer |year=1895 |volume=3}}</ref> |

|||

Some 21st century studies have found that ichthyosaurs, [[Thalattosauria|thalattosaurs]] and sauropterygians were close relatives, either as [[Archosauromorpha|stem-archosaurs]]<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wolniewicz |first1=Andrzej S |last2=Shen |first2=Yuefeng |last3=Li |first3=Qiang |last4=Sun |first4=Yuanyuan |last5=Qiao |first5=Yu |last6=Chen |first6=Yajie |last7=Hu |first7=Yi-Wei |last8=Liu |first8=Jun |date=2023-08-08 |editor-last=Ibrahim |editor-first=Nizar |editor2-last=Perry |editor2-first=George H |editor3-last=Benton |editor3-first=Michael |title=An armoured marine reptile from the Early Triassic of South China and its phylogenetic and evolutionary implications |journal=eLife |volume=12 |pages=e83163 |doi=10.7554/eLife.83163 |doi-access=free |issn=2050-084X |pmc=10499374 |pmid=37551884}}</ref> or as stem-saurians.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Neenan |first1=James M. |last2=Klein |first2=Nicole |last3=Scheyer |first3=Torsten M. |date=2013-03-27 |title=European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms2633 |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=1621 |doi=10.1038/ncomms2633 |pmid=23535642 |bibcode=2013NatCo...4.1621N |issn=2041-1723}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Jiang |first1=Baoyu |last2=He |first2=Yiming |last3=Elsler |first3=Armin |last4=Wang |first4=Shengyu |last5=Keating |first5=Joseph N. |last6=Song |first6=Junyi |last7=Kearns |first7=Stuart L. |last8=Benton |first8=Michael J. |date=2023 |title=Extended embryo retention and viviparity in the first amniotes |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |language=en |volume=7 |issue=7 |pages=1131–1140 |doi=10.1038/s41559-023-02074-0 |issn=2397-334X |pmc=10333127 |pmid=37308704|bibcode=2023NatEE...7.1131J }}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 20: | Line 21: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

{{Sauropsida|N.}} |

|||

[[Category:Polyphyletic groups]] |

|||

[[Category:Prehistoric marine reptiles]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric marine reptiles]] |

||

[[Category:Prehistoric reptile taxonomy]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric reptile taxonomy]] |

||

{{paleo-reptile-stub}} |

{{paleo-reptile-stub}} |

||

Latest revision as of 01:07, 22 February 2024

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bones articulate. They are different from Synapsida, which also have a single opening behind the orbit, by the placement of the fenestra. In synapsids, this opening is below the articulation of the post-orbital and squamosal bones. It is now commonly believed that euryapsids (particularly sauropterygians) are in fact diapsids (which have two fenestrae behind the orbit) that lost the lower temporal fenestra. Euryapsids are usually considered entirely extinct, although turtles might be part of the sauropterygian clade[1] while other authors disagree.[2] Euryapsida may also be a synonym of Sauropterygia sensu lato.[3]

The ichthyosaurian skull is sometimes described as having a metapsid (or parapsid) condition instead of a truly euryapsid one. In ichthyosaurs, the squamosal bone is never part of the fenestra's margin.[4] Parapsida was originally a taxon consisting of ichthyosaurs, squamates, protorosaurs, araeoscelidans and pleurosaurs.[3]

Historically, a variety of reptiles with upper fenestrae, either alone or with a lower emargination, have been considered euryapsid or parapsid, and to have had their patterns of fenestration originate separately from those of diapsids. This includes araeoscelidans, mesosaurs, squamates, pleurosaurids,[5] weigeltisaurids, protorosaurs, and trilophosaurs.[6][7] With the exception of mesosaurs, which only have the lower temporal opening, all of these are universally agreed to be diapsids which either secondarily closed the lower opening (araeoscelids, trilophosaurs) or lost the lower bar (squamates, pleurosaurs, protorosaurs).

Euryapsida was proposed by Edwin H. Colbert as a substitute for the earlier term Synaptosauria, originally created by Edward D. Cope for a taxon including sauropterygians, turtles and rhynchocephalians. Baur removed the rhynchocephalians from Synaptosauria and Williston later resurrected the taxon, including only Sauropterygia (Nothosauria and Plesiosauria) and Placodontia in it.[3]

The terms Enaliosauria and Halisauria have also been used for a taxon including ichthyosaurs and sauropterygians.[8][9]

Some 21st century studies have found that ichthyosaurs, thalattosaurs and sauropterygians were close relatives, either as stem-archosaurs[2][10] or as stem-saurians.[11][12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lee, M. S. Y. (2013). "Turtle origins: insights from phylogenetic retrofitting and molecular scaffolds". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26 (12): 2729–2738. doi:10.1111/jeb.12268. PMID 24256520.

- ^ a b Simões, Tiago R.; Kammerer, Christian F.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Pierce, Stephanie E. (2022-08-19). "Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles". Science Advances. 8 (33): eabq1898. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.1898S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq1898. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 9390993. PMID 35984885.

- ^ a b c Rieppel, Olivier (1989-01-04). "A new pachypleurosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of Monte San Giorgio, Switzerland". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences. 323 (1212): 1–73. doi:10.1098/rstb.1989.0001. ISSN 0080-4622.

- ^ Maisch, M. (2010). "Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art". Palaeodiversity. 3: 151–214. S2CID 87979321.

- ^ Williston, Samuel Wendell (1925). Osteology of the Reptiles.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood (1956). Osteology of the Reptiles.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood (1966). Vertebrate Paleontology (3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ "Enaliosauria". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1895). Die systematische Phylogenie (Dritter Theil/Systematische Phylogenie der Wirbelthiere (Vertebrata)). Vol. 3. Georg Reimer.

- ^ Wolniewicz, Andrzej S; Shen, Yuefeng; Li, Qiang; Sun, Yuanyuan; Qiao, Yu; Chen, Yajie; Hu, Yi-Wei; Liu, Jun (2023-08-08). Ibrahim, Nizar; Perry, George H; Benton, Michael (eds.). "An armoured marine reptile from the Early Triassic of South China and its phylogenetic and evolutionary implications". eLife. 12: e83163. doi:10.7554/eLife.83163. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 10499374. PMID 37551884.

- ^ Neenan, James M.; Klein, Nicole; Scheyer, Torsten M. (2013-03-27). "European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia". Nature Communications. 4 (1): 1621. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1621N. doi:10.1038/ncomms2633. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 23535642.

- ^ Jiang, Baoyu; He, Yiming; Elsler, Armin; Wang, Shengyu; Keating, Joseph N.; Song, Junyi; Kearns, Stuart L.; Benton, Michael J. (2023). "Extended embryo retention and viviparity in the first amniotes". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 7 (7): 1131–1140. Bibcode:2023NatEE...7.1131J. doi:10.1038/s41559-023-02074-0. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 10333127. PMID 37308704.