Three Hundred Years Hence: Difference between revisions

Tassedethe (talk | contribs) m v2.02 - Repaired 1 link to disambiguation page - (You can help) - Mary Griffith |

wikisource links |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|1836 novel by Mary Griffith}} |

|||

{{Infobox book |

{{Infobox book |

||

| name = Three Hundred Years Hence |

| name = Three Hundred Years Hence |

||

| Line 21: | Line 22: | ||

| preceded_by = |

| preceded_by = |

||

| followed_by = |

| followed_by = |

||

| wikisource = Three Hundred Years Hence |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

The novel concerns a hero who falls into a deep sleep and awakens in the Utopian states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. |

The novel concerns a hero who falls into a deep sleep and awakens in the Utopian states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. |

||

==Influences and successors== |

|||

==Successors== |

|||

Writers of utopian fiction generally need to set their imagined societies either in a remote place (as in Sir [[Thomas More]]'s original ''[[Utopia (book)|Utopia]]'' and many imitators), or in a different time. Griffith was the earliest American writer to project her protagonist into the future to encounter a vastly improved social order. Many successors would follow her example; most famously, [[Edward Bellamy]] used the same trick in his ''[[Looking Backward]]'' (1888), as did many of the writers who produced [[List of sequels to Looking Backward|sequels and responses]] to his work. The same tactic is exploited in John Macnie's ''[[The Diothas]]'' (1883), [[William Henry Hudson|W. H. Hudson]]'s ''[[A Crystal Age]]'' (1887), Elizabeth Corbett's ''[[New Amazonia]]'' (1889), Bradford Peck's ''[[The World a Department Store]]'' (1900), [[Charlotte Perkins Gilman]]'s ''[[Moving the Mountain (novel)|Moving the Mountain]]'' (1911), and other works. |

Writers of utopian fiction generally need to set their imagined societies either in a remote place (as in Sir [[Thomas More]]'s original ''[[Utopia (More book)|Utopia]]'' and many imitators), or in a different time. Griffith's story was likely inspired by ''[[Memoirs of the Year 2500]]'' by French writer [[Louis-Sébastien Mercier]].<ref name="DarlingWalker2019">{{cite book|author1=Elizabeth Darling|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DDOoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT103|title=Suffragette City: Women, Politics, and the Built Environment|author2=Nathaniel Robert Walker|date=8 August 2019|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-1-351-33391-7|page=103}}</ref> Griffith was however the earliest American writer to project her protagonist into the future to encounter a vastly improved social order. Many successors would follow her example; most famously, [[Edward Bellamy]] used the same trick in his ''[[Looking Backward]]'' (1888), as did many of the writers who produced [[List of sequels to Looking Backward|sequels and responses]] to his work. The same tactic is exploited in John Macnie's ''[[The Diothas]]'' (1883), [[William Henry Hudson|W. H. Hudson]]'s ''[[A Crystal Age]]'' (1887), Elizabeth Corbett's ''[[New Amazonia]]'' (1889), Bradford Peck's ''[[The World a Department Store]]'' (1900), [[Charlotte Perkins Gilman]]'s ''[[Moving the Mountain (novel)|Moving the Mountain]]'' (1911), and other works. |

||

Another, later book, published in 1881 by [[William Delisle Hay]], was given the same title (''Three Hundred Years Hence or A Voice From Posterity''), probably in ignorance of Griffith's earlier but then-obscure work. |

Another, later book, published in 1881 by [[William Delisle Hay]], was given the same title (''Three Hundred Years Hence or A Voice From Posterity''), probably in ignorance of Griffith's earlier but then-obscure work. |

||

| Line 53: | Line 55: | ||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

== |

==Further reading== |

||

*{{cite book | last=Chalker | first=Jack L. | authorlink=Jack L. Chalker |author2=Mark Owings | title=The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923-1998 | location=Westminster, MD and Baltimore | publisher=Mirage Press, Ltd.| pages=530 | year=1998}} |

*{{cite book | last=Chalker | first=Jack L. | authorlink=Jack L. Chalker |author2=Mark Owings | title=The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923-1998 | location=Westminster, MD and Baltimore | publisher=Mirage Press, Ltd.| pages=530 | year=1998}} |

||

*{{cite book | last=Tuck | first=Donald H. | authorlink=Donald H. Tuck | title=The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy | location=Chicago | publisher=[[Advent (publisher)|Advent]] | pages=11 | year=1978|isbn=0-911682-20-1}} |

*{{cite book | last=Tuck | first=Donald H. | authorlink=Donald H. Tuck | title=The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy | location=Chicago | publisher=[[Advent (publisher)|Advent]] | pages=11 | year=1978|isbn=0-911682-20-1}} |

||

{{wikisource}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 62: | Line 65: | ||

[[Category:American science fiction novels]] |

[[Category:American science fiction novels]] |

||

[[Category:Utopian novels]] |

[[Category:Utopian novels]] |

||

{{US-novel-stub}} |

|||

{{1830s-novel-stub}} |

|||

Latest revision as of 11:26, 25 March 2024

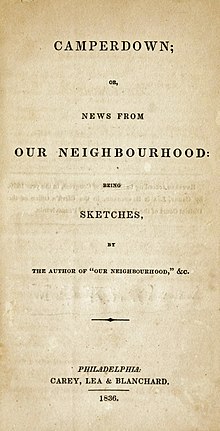

First edition title page | |

| Author | Mary Griffith |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Utopian Science fiction novel |

| Publisher | Prime Press |

Publication date | 1836 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 131 |

| ISBN | 978-1514738016 |

| OCLC | 3253783 |

| Text | Three Hundred Years Hence at Wikisource |

Three Hundred Years Hence is a utopian science fiction novel by author Mary Griffith, published in 1836. It is the first known utopian novel written by an American woman.[1] The novel was originally published in 1836 as part of Griffith's collection, Camperdown, or News from Our Neighborhood, and later published by Prime Press in 1950 in an edition of 300 copies.

Plot introduction

[edit]The novel concerns a hero who falls into a deep sleep and awakens in the Utopian states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York.

Influences and successors

[edit]Writers of utopian fiction generally need to set their imagined societies either in a remote place (as in Sir Thomas More's original Utopia and many imitators), or in a different time. Griffith's story was likely inspired by Memoirs of the Year 2500 by French writer Louis-Sébastien Mercier.[2] Griffith was however the earliest American writer to project her protagonist into the future to encounter a vastly improved social order. Many successors would follow her example; most famously, Edward Bellamy used the same trick in his Looking Backward (1888), as did many of the writers who produced sequels and responses to his work. The same tactic is exploited in John Macnie's The Diothas (1883), W. H. Hudson's A Crystal Age (1887), Elizabeth Corbett's New Amazonia (1889), Bradford Peck's The World a Department Store (1900), Charlotte Perkins Gilman's Moving the Mountain (1911), and other works.

Another, later book, published in 1881 by William Delisle Hay, was given the same title (Three Hundred Years Hence or A Voice From Posterity), probably in ignorance of Griffith's earlier but then-obscure work.

Critical reception

[edit]Reviewing the 1950 edition, Boucher and McComas characterized the novel as "an odd and delightful item of 1836 dealing with a strongly feminist future.".[3]

Publication history

[edit]- 1836, US, Carey, Lea & Blanchard OCLC 12851342, Pub date 1836, Hardback, included in Camperdown, or News from Our Neighborhood

- 1950, US, Prime Press OCLC 3253783, Pub date 1950, Hardback, first separate publication

- 1975, US, Gregg Press ISBN 0-8398-2303-7, Pub date 1975, Hardback

Notes

[edit]- ^ Suksang, Duangrudi (2000-01-01). "Mary Griffith's Pioneering Vision: Three Hundred Years Hence". Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ Elizabeth Darling; Nathaniel Robert Walker (8 August 2019). Suffragette City: Women, Politics, and the Built Environment. Taylor & Francis. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-351-33391-7.

- ^ "Recommended Reading," F&SF, December 1950, p.104

Further reading

[edit]- Chalker, Jack L.; Mark Owings (1998). The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923-1998. Westminster, MD and Baltimore: Mirage Press, Ltd. p. 530.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1978). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. p. 11. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.