Halogenation: Difference between revisions

"In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction which introduces of one or more halogens into a chemical compound." Removed OF Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| (92 intermediate revisions by 24 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Chemical reaction which adds one or more halogen elements to a compound}} |

|||

{{redirect|Fluorination|the addition of fluoride to drinking water|Water fluoridation}} |

{{redirect|Fluorination|the addition of fluoride to drinking water|Water fluoridation}} |

||

{{for|the addition of chlorine, hypochlorite, etc. to drinking water|Water chlorination}} |

{{for|the addition of chlorine, hypochlorite, etc. to drinking water|Water chlorination}} |

||

In [[chemistry]], '''halogenation''' is a [[chemical reaction]] which introduces one or more [[halogen]]s into a [[chemical compound]]. [[Halide]]-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of [[polymers]], [[drugs]].<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1002/9780470771723.ch3|chapter=Formation of Carbon-Halogen Bonds|title=Halides, Pseudo-Halides and Azides: Part 2 (1983)|year=1983|last1=Hudlicky|first1=Milos|last2=Hudlicky|first2=Tomas|pages=1021–1172|isbn=9780470771723|editor1=S. Patai|editor2=Z. Rappoport|series=PATAI's Chemistry of Functional Groups}}</ref> This kind of conversion is in fact so common that a comprehensive overview is challenging. This article mainly deals with halogenation using elemental halogens ({{chem2|[[Fluorine|F2]], [[Chlorine|Cl2]], [[Bromine|Br2]], [[Iodine|I2]]}}). Halides are also commonly introduced using salts of the halides and halogen acids.{{cln|reason=What on this Earth is "halogen acids"???|date=July 2023}} Many specialized [[reagent]]s exist for and introducing halogens into diverse [[Substrate (chemistry)|substrates]], e.g. [[thionyl chloride]]. |

|||

'''Halogenation''' is a [[chemical reaction]] that involves the addition of one or more [[halogen]]s to a compound or material. The pathway and [[stoichiometry]] of halogenation depends on the structural features and functional groups of the organic substrate, as well as on the specific halogen. Inorganic compounds such as metals also undergo halogenation. |

|||

==Organic chemistry== |

==Organic chemistry== |

||

| ⚫ | Several pathways exist for the halogenation of organic compounds, including [[free radical halogenation]], [[ketone halogenation]], [[electrophilic halogenation]], and [[halogen addition reaction]]. The nature of the [[Substrate (chemistry)|substrate]] determines the pathway. The facility of halogenation is influenced by the halogen. [[Fluorine]] and [[chlorine]] are more [[electrophilic]] and are more aggressive halogenating agents. [[Bromine]] is a weaker halogenating agent than both fluorine and chlorine, while [[iodine]] is the least reactive of them all. The facility of [[dehydrohalogenation]] follows the reverse trend: iodine is most easily removed from organic compounds, and [[organofluorine]] compounds are highly stable. |

||

=== |

===Free radical halogenation === |

||

Halogenation of [[saturated hydrocarbon]]s is a [[substitution reaction]]. The reaction typically involves [[free radical]] pathways. The [[regiochemistry]] of the halogenation of [[alkanes]] is largely determined by the relative weakness of the [[Carbon–hydrogen bond|C–H bonds]]. This trend is reflected by the faster reaction at [[Tertiary (chemistry)|tertiary]] and [[Secondary (chemistry)|secondary]] positions. |

|||

Several pathways exist for the halogenation of organic compounds, including [[free radical halogenation]], [[ketone halogenation]], [[electrophilic halogenation]], and [[halogen addition reaction]]. The structure of the substrate is one factor that determines the pathway. |

|||

Free radical chlorination is used for the industrial production of some [[solvents]]:<ref name=Ullmann>{{Ullmann|doi=10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:{{chem2|CH4 + Cl2 → CH3Cl + HCl}} |

|||

Saturated hydrocarbons typically do not add halogens but undergo free radical halogenation, involving substitution of hydrogen atoms by halogen. The regiochemistry of the halogenation of alkanes is usually determined by the relative weakness of the available C–H bonds. The preference for reaction at tertiary and secondary positions results from greater stability of the corresponding free radicals and the transition state leading to them. Free radical halogenation is used for the industrial production of chlorinated methanes:<ref name=Ullmann>M. Rossberg et al. “Chlorinated Hydrocarbons” in ''Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry'' 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. {{DOI|10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2}}</ref> |

|||

:CH<sub>4</sub> + Cl<sub>2</sub> → CH<sub>3</sub>Cl + HCl |

|||

Rearrangement often accompany such free radical reactions. |

|||

| ⚫ | Naturally-occurring [[organobromine compound]]s are usually produced by free radical pathway [[catalyzed]] by the [[enzyme]] [[bromoperoxidase]]. The reaction requires [[bromide]] in combination with [[oxygen]] as an [[oxidant]]. The [[oceans]] are estimated to release 1–2 [[million]] tons of [[bromoform]] and 56,000 tons of [[bromomethane]] annually.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1039/a900201d|title=The diversity of naturally occurring organobromine compounds|year=1999|last1=Gribble|first1=Gordon W.|journal=Chemical Society Reviews|volume=28|issue=5|pages=335–346}}</ref>{{cln|reason=Which ton??? Short ton, long ton or metric ton???|date=July 2023}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

:RCH=CHR′ + X<sub>2</sub> → RCHX–CHXR′ |

|||

| ⚫ | The addition of halogens to alkenes proceeds via intermediate [[halonium ion]]s. In special cases, such intermediates have been isolated.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = [[Chem. Commun.]] | year = 1998 | pages = 927–928 | doi = 10.1039/a709063c | title = X-Ray structure of bridged 2,2′-bi(adamant-2-ylidene) chloronium cation and comparison of its reactivity with a singly bonded chloroarenium cation |author1=T. Mori |author2=R. Rathore | issue = 8 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[iodoform reaction]], which involves degradation of [[methyl ketone]]s, proceeds by the free radical iodination. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Aromatic compounds are subject to electrophilic halogenation:<ref>Illustrative procedure for chlorination of an aromatic compound: {{OrgSynth|author=Edward R. Atkinson, Donald M. Murphy, and James E. Lufkin |year=1951|title=''dl''-4,4′,6,6′-Tetrachlorodiphenic Acid|collvol=4| collvolpages=872|prep=CV4P0872}}</ref> |

|||

:RC<sub>6</sub>H<sub>5</sub> + X<sub>2</sub> → HX + RC<sub>6</sub>H<sub>4</sub>X |

|||

This reaction works only for chlorine and bromine and is carried in the presence of a Lewis acid such as FeX<sub>3</sub> (laboratory method). The role of the Lewis acid is to polarize the halogen-halogen bond, making the halogen molecule more electrophilic. Industrially, this is done by treating the aromatic compound with X<sub>2</sub> in the presence of iron metal. When the halogen is pumped into the reaction vessel, it reacts with iron, generating FeX<sub>3</sub> in catalytic amounts. The reaction mechanism can be represented as follows: |

|||

[[File:Arr.jpg|thumb|centre|Halogenation of benzene|500x400px]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Because of its extreme reactivity, fluorine ({{chem2|F2}}) represents a special category with respect to halogenation. Most organic compounds, saturated or otherwise, burn upon contact with {{chem2|F2}}, ultimately yielding [[carbon tetrafluoride]]. By contrast, the heavier halogens are far less reactive toward saturated hydrocarbons. |

|||

Highly specialised conditions and apparatus are required for fluorinations with elemental [[fluorine]]. Commonly, fluorination reagents are employed instead of {{chem2|F2}}. Such reagents include [[cobalt trifluoride]], [[chlorine trifluoride]], and [[iodine pentafluoride]].<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1002/14356007.a11_307 |chapter=Fluorine Compounds, Inorganic |title=Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry |date=2000 |last1=Aigueperse |first1=Jean |last2=Mollard |first2=Paul |last3=Devilliers |first3=Didier |last4=Chemla |first4=Marius |last5=Faron |first5=Robert |last6=Romano |first6=René |last7=Cuer |first7=Jean Pierre |isbn=3-527-30673-0 }}</ref> |

|||

For iodine, however, oxidising conditions must be used in order to perform iodination. Because iodination is a reversible process, the products have to be removed from the reaction medium in order to drive the reaction forward, see [[Le Chatelier's principle]]. This can be done by conducting the reaction in the presence of an oxidising agent that oxidises HI to I<sub>2</sub>, thus removing HI from the reaction and generating more iodine that can further react. The reaction steps involved in iodination are the following: |

|||

[[File:IODM.jpg|thumb|Iodination of benzene|400x400px]] |

|||

The method [[electrochemical fluorination]] is used commercially for the production of [[perfluorinated compound]]s. It generates small amounts of elemental fluorine [[in situ]] from [[hydrogen fluoride]]. The method avoids the hazards of handling fluorine gas. Many commercially important [[organic compounds]] are fluorinated using this technology. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:96. Адиција на хлор на етин.ogg|thumb|right|Double-addition of [[chlorine gas]] to [[ethyne]]]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:{{chem2|R\sCH\dCH\sR' + X2 → R\sCHX\sCHX\sR'}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:{{chem2|4 HCl + 2 CH2\dCH2 + O2 → 2 Cl\sCH2\sCH2\sCl + 2 H2O}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The addition of halogens to alkenes proceeds via [[Reaction intermediate|intermediate]] [[halonium ion]]s. In special cases, such intermediates have been isolated.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = [[Chem. Commun.]] | year = 1998 | pages = 927–928 | doi = 10.1039/a709063c | title = X-Ray structure of bridged 2,2′-bi(adamant-2-ylidene) chloronium cation and comparison of its reactivity with a singly bonded chloroarenium cation |author1=T. Mori |author2=R. Rathore | issue = 8 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Bromination is more [[chemical selectivity|selective]] than chlorination because the reaction is less [[exothermic]]. Illustrative of the bromination of an alkene is the route to the [[anesthetic]] [[halothane]] from [[trichloroethylene]]:<ref>''Synthesis of Essential Drugs'', Ruben Vardanyan, Victor Hruby; Elsevier 2005 {{ISBN|0-444-52166-6}}</ref> |

||

Another method to obtain aromatic iodides is [[Sandmeyer reaction]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Iodination and bromination can be effected by the addition of [[iodine]] and [[bromine]] to alkenes. The reaction, which conveniently proceeds with the discharge of the color of {{chem2|I2 and Br2}}, is the basis of the [[analytical method]]. The [[iodine number]] and [[bromine number]] are measures of the [[degree of unsaturation]] for [[fat]]s and other organic compounds. |

|||

====Other halogenation methods==== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:RCO<sub>2</sub>Ag + Br<sub>2</sub> → RBr + CO<sub>2</sub> + AgBr |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[Sandmeyer reaction]] is used to give aryl halides from [[diazonium salt]]s, which are obtained from [[aniline]]s. |

|||

{{main|Aryl halide}} |

|||

[[Aromatic compound]]s are subject to [[electrophilic halogenation]]: |

|||

:{{chem2|R\sC6H5 + X2 → HX + R\sC6H4\sX}} |

|||

This kind of reaction typically works well for [[chlorine]] and [[bromine]]. Often a [[Lewis acid]]ic [[catalyst]] is used, such as [[ferric chloride]].<ref name=PhCl>{{cite book |doi=10.1002/14356007.o06_o03 |chapter=Chlorinated Benzenes and Other Nucleus-Chlorinated Aromatic Hydrocarbons |title=Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry |year=2011 |last1=Beck |first1=Uwe |last2=Löser |first2=Eckhard |isbn=978-3527306732 }}</ref> Many detailed procedures are available.<ref>Organic chemistry by Jonathan Clayden, Nick Grieves, Stuart Warren, Oxford University Press</ref><ref>{{OrgSynth|author=Edward R. Atkinson, Donald M. Murphy, and James E. Lufkin |year=1951|title=''dl''-4,4′,6,6′-Tetrachlorodiphenic Acid|volume=31| page=96|doi=10.15227/orgsyn.031.0096}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

In the [[Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky halogenation]], carboxylic acids are alpha-halogenated. |

|||

| ⚫ | In the [[Hunsdiecker reaction]], [[carboxylic acids]] are converted to [[organic halide]], whose [[carbon chain]] is shortened by one [[carbon]] atom with respect to the carbon chain of the particular carboxylic acid. The carboxylic acid is first converted to its [[silver]] salt, which is then oxidized with [[halogen]]: |

||

:{{chem2|R\sCOO−Ag+ + [[Bromine|Br2]] → R\sBr + [[carbon dioxide|CO2]] + [[Silver bromide|Ag+Br−]]}} |

|||

:{{chem2|[[Silver acetate|CH3\sCOO−Ag+]] + Br2 → [[Bromomethane|CH3\sBr]] + CO2 + Ag+Br−}} |

|||

Many [[organometallic compound]]s react with halogens to give the organic halide: |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

:{{chem2|RM + X2 → RX + MX}} |

|||

:2 HCl + CH<sub>2</sub>=CH<sub>2</sub> + {{1/2}} O<sub>2</sub> → ClCH<sub>2</sub>CH<sub>2</sub>Cl + H<sub>2</sub>O |

|||

:{{chem2|[[n-Butyllithium|CH3CH2CH2CH2Li]] + [[Chlorine|Cl2]] → [[1-chlorobutane|CH3CH2CH2CH2Cl]] + [[Lithium chloride|LiCl]]}} |

|||

=== Halogenation by halogen type === |

|||

| ⚫ | The facility of halogenation is influenced by the halogen. [[Fluorine]] and [[chlorine]] are more [[electrophilic]] and are more aggressive halogenating agents. [[Bromine]] is a weaker halogenating agent than both fluorine and chlorine, while [[iodine]] is the least reactive of them all. The facility of dehydrohalogenation follows the reverse trend: iodine is most easily removed from organic compounds, and organofluorine compounds are highly stable. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Organic compounds, saturated and unsaturated alike, react readily, usually explosively, with fluorine. Fluorination with elemental fluorine (F<sub>2</sub>) requires highly specialised conditions and apparatus. Many commercially important organic compounds are fluorinated electrochemically using [[hydrogen fluoride]] as the source of fluorine. The method is called [[electrochemical fluorination]]. Aside from F<sub>2</sub> and its electrochemically generated equivalent, a variety of fluorinating [[reagent]]s are known such as [[xenon difluoride]] and [[cobalt(III) fluoride]]. |

|||

==== Chlorination ==== |

|||

:See also: [[Photochlorination]] |

|||

Chlorination is generally highly [[exothermic]]. Both saturated and unsaturated compounds react directly with chlorine, the former usually requiring UV light to initiate [[homolysis (chemistry)|homolysis]] of chlorine. Chlorination is conducted on a large scale industrially; major processes include routes to [[1,2-dichloroethane]] (a precursor to [[PVC]]), as well as various chlorinated ethanes, as solvents. |

|||

====Bromination==== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

====Iodination==== |

|||

Iodine is the least reactive halogen and is reluctant to react with most organic compounds. The addition of iodine to alkenes is the basis of the analytical method called the [[iodine number]], a measure of the degree of unsaturation for [[fat]]s. The [[iodoform reaction]] involves degradation of methyl ketones. |

|||

==Inorganic chemistry== |

==Inorganic chemistry== |

||

All elements aside from argon, neon, and helium form fluorides by direct reaction with [[fluorine]]. Chlorine is slightly more selective, but still reacts with most metals and heavier nonmetals. Following the usual trend, bromine is less reactive and iodine least of all. Of the many reactions possible, illustrative is the formation of [[gold(III) chloride]] by the chlorination of [[gold]]. The chlorination of metals is usually not very important industrially since the chlorides are more easily made from the oxides and |

All [[Chemical element|elements]] aside from [[argon]], [[neon]], and [[helium]] form [[fluorides]] by direct reaction with [[fluorine]]. [[Chlorine]] is slightly more selective, but still reacts with most [[metals]] and heavier [[nonmetals]]. Following the usual trend, [[bromine]] is less [[Reactivity (chemistry)|reactive]] and [[iodine]] least of all. Of the many reactions possible, illustrative is the formation of [[gold(III) chloride]] by the chlorination of [[gold]]. The chlorination of metals is usually not very important industrially since the [[chlorides]] are more easily made from the [[oxides]] and [[hydrogen chloride]]. Where chlorination of [[inorganic compounds]] is practiced on a relatively large scale is for the production of [[phosphorus trichloride]] and [[disulfur dichloride]].<ref>{{Greenwood&Earnshaw2nd}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Latest revision as of 15:24, 12 June 2024

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction which introduces one or more halogens into a chemical compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polymers, drugs.[1] This kind of conversion is in fact so common that a comprehensive overview is challenging. This article mainly deals with halogenation using elemental halogens (F2, Cl2, Br2, I2). Halides are also commonly introduced using salts of the halides and halogen acids.[clarification needed] Many specialized reagents exist for and introducing halogens into diverse substrates, e.g. thionyl chloride.

Organic chemistry

[edit]Several pathways exist for the halogenation of organic compounds, including free radical halogenation, ketone halogenation, electrophilic halogenation, and halogen addition reaction. The nature of the substrate determines the pathway. The facility of halogenation is influenced by the halogen. Fluorine and chlorine are more electrophilic and are more aggressive halogenating agents. Bromine is a weaker halogenating agent than both fluorine and chlorine, while iodine is the least reactive of them all. The facility of dehydrohalogenation follows the reverse trend: iodine is most easily removed from organic compounds, and organofluorine compounds are highly stable.

Free radical halogenation

[edit]Halogenation of saturated hydrocarbons is a substitution reaction. The reaction typically involves free radical pathways. The regiochemistry of the halogenation of alkanes is largely determined by the relative weakness of the C–H bonds. This trend is reflected by the faster reaction at tertiary and secondary positions.

Free radical chlorination is used for the industrial production of some solvents:[2]

- CH4 + Cl2 → CH3Cl + HCl

Naturally-occurring organobromine compounds are usually produced by free radical pathway catalyzed by the enzyme bromoperoxidase. The reaction requires bromide in combination with oxygen as an oxidant. The oceans are estimated to release 1–2 million tons of bromoform and 56,000 tons of bromomethane annually.[3][clarification needed]

The iodoform reaction, which involves degradation of methyl ketones, proceeds by the free radical iodination.

Fluorination

[edit]Because of its extreme reactivity, fluorine (F2) represents a special category with respect to halogenation. Most organic compounds, saturated or otherwise, burn upon contact with F2, ultimately yielding carbon tetrafluoride. By contrast, the heavier halogens are far less reactive toward saturated hydrocarbons.

Highly specialised conditions and apparatus are required for fluorinations with elemental fluorine. Commonly, fluorination reagents are employed instead of F2. Such reagents include cobalt trifluoride, chlorine trifluoride, and iodine pentafluoride.[4]

The method electrochemical fluorination is used commercially for the production of perfluorinated compounds. It generates small amounts of elemental fluorine in situ from hydrogen fluoride. The method avoids the hazards of handling fluorine gas. Many commercially important organic compounds are fluorinated using this technology.

Addition of halogens to alkenes and alkynes

[edit]Unsaturated compounds, especially alkenes and alkynes, add halogens:

- R−CH=CH−R' + X2 → R−CHX−CHX−R'

In oxychlorination, the combination of hydrogen chloride and oxygen serves as the equivalent of chlorine, as illustrated by this route to 1,2-dichloroethane:

- 4 HCl + 2 CH2=CH2 + O2 → 2 Cl−CH2−CH2−Cl + 2 H2O

The addition of halogens to alkenes proceeds via intermediate halonium ions. In special cases, such intermediates have been isolated.[5]

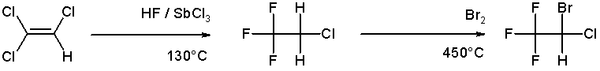

Bromination is more selective than chlorination because the reaction is less exothermic. Illustrative of the bromination of an alkene is the route to the anesthetic halothane from trichloroethylene:[6]

Iodination and bromination can be effected by the addition of iodine and bromine to alkenes. The reaction, which conveniently proceeds with the discharge of the color of I2 and Br2, is the basis of the analytical method. The iodine number and bromine number are measures of the degree of unsaturation for fats and other organic compounds.

Halogenation of aromatic compounds

[edit]Aromatic compounds are subject to electrophilic halogenation:

- R−C6H5 + X2 → HX + R−C6H4−X

This kind of reaction typically works well for chlorine and bromine. Often a Lewis acidic catalyst is used, such as ferric chloride.[7] Many detailed procedures are available.[8][9] Because fluorine is so reactive, other methods, such as the Balz–Schiemann reaction, are used to prepare fluorinated aromatic compounds.

Other halogenation methods

[edit]In the Hunsdiecker reaction, carboxylic acids are converted to organic halide, whose carbon chain is shortened by one carbon atom with respect to the carbon chain of the particular carboxylic acid. The carboxylic acid is first converted to its silver salt, which is then oxidized with halogen:

- R−COO−Ag+ + Br2 → R−Br + CO2 + Ag+Br−

- CH3−COO−Ag+ + Br2 → CH3−Br + CO2 + Ag+Br−

Many organometallic compounds react with halogens to give the organic halide:

- RM + X2 → RX + MX

- CH3CH2CH2CH2Li + Cl2 → CH3CH2CH2CH2Cl + LiCl

Inorganic chemistry

[edit]All elements aside from argon, neon, and helium form fluorides by direct reaction with fluorine. Chlorine is slightly more selective, but still reacts with most metals and heavier nonmetals. Following the usual trend, bromine is less reactive and iodine least of all. Of the many reactions possible, illustrative is the formation of gold(III) chloride by the chlorination of gold. The chlorination of metals is usually not very important industrially since the chlorides are more easily made from the oxides and hydrogen chloride. Where chlorination of inorganic compounds is practiced on a relatively large scale is for the production of phosphorus trichloride and disulfur dichloride.[10]

See also

[edit]- Dehalogenation

- Haloalkane (Alkyl halide)

- Halogenoarene (Aryl halide)

- Free radical halogenation

- Haloketone

- Electrophilic substitution

References

[edit]- ^ Hudlicky, Milos; Hudlicky, Tomas (1983). "Formation of Carbon-Halogen Bonds". In S. Patai; Z. Rappoport (eds.). Halides, Pseudo-Halides and Azides: Part 2 (1983). PATAI's Chemistry of Functional Groups. pp. 1021–1172. doi:10.1002/9780470771723.ch3. ISBN 9780470771723.

- ^ Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_233.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Gribble, Gordon W. (1999). "The diversity of naturally occurring organobromine compounds". Chemical Society Reviews. 28 (5): 335–346. doi:10.1039/a900201d.

- ^ Aigueperse, Jean; Mollard, Paul; Devilliers, Didier; Chemla, Marius; Faron, Robert; Romano, René; Cuer, Jean Pierre (2000). "Fluorine Compounds, Inorganic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_307. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ T. Mori; R. Rathore (1998). "X-Ray structure of bridged 2,2′-bi(adamant-2-ylidene) chloronium cation and comparison of its reactivity with a singly bonded chloroarenium cation". Chem. Commun. (8): 927–928. doi:10.1039/a709063c.

- ^ Synthesis of Essential Drugs, Ruben Vardanyan, Victor Hruby; Elsevier 2005 ISBN 0-444-52166-6

- ^ Beck, Uwe; Löser, Eckhard (2011). "Chlorinated Benzenes and Other Nucleus-Chlorinated Aromatic Hydrocarbons". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.o06_o03. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Organic chemistry by Jonathan Clayden, Nick Grieves, Stuart Warren, Oxford University Press

- ^ Edward R. Atkinson, Donald M. Murphy, and James E. Lufkin (1951). "dl-4,4′,6,6′-Tetrachlorodiphenic Acid". Organic Syntheses. 31: 96. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.031.0096

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.