Jakub Arbes: Difference between revisions

removed Category:People from Prague; added Category:Writers from Prague using HotCat |

m date format audit, link maintenance, minor formatting |

||

| (37 intermediate revisions by 25 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Czech writer of prose narratives}} |

|||

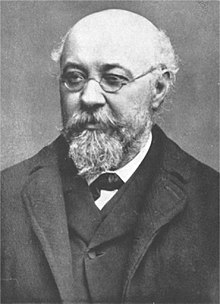

[[File:Jakub Arbes 1884 Mara.png|thumb|Jakub Arbes (1884)]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2024}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Infobox writer |

|||

| name = Jakub Arbes |

|||

| image = Jakub Arbes.jpg |

|||

| imagesize = |

|||

| caption = Jakub Arbes (1884) |

|||

| pseudonym = |

|||

| birth_name = |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1840|6|12}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Prague]], Austrian Empire |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1914|4|8|1840|6|12}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Prague]], Austria-Hungary |

|||

| resting_place = [[Smíchov|Praha-Smíchov]] |

|||

| occupation = Writer and journalist |

|||

| language = [[Czech language|Czech]] |

|||

| nationality = [[Czechs|Czech]] |

|||

| period = |

|||

| genre = |

|||

| subject = |

|||

| movement = |

|||

| notableworks = |

|||

| partner = Josefina Rabochová |

|||

| children = |

|||

| relatives = |

|||

| influences = |

|||

| influenced = |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| signature = Signatura Arbes.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== Life and Politics == |

== Life and Politics == |

||

A native of |

A native of Smíchov in Prague, Arbes studied under [[Jan Neruda]], for whom he had a lifelong admiration, and later he studied Philosophy and Literature at [[Prague Polytechnic]]. In 1867, he began his career in journalism as editor of ''Vesna Kutnohorská'', and from 1868 to 1877, as the chief editor of the National Press. Arbes was also an editor of political magazines ''Hlas'' (The Voice) and ''Politiks'' (Politics), and a sympathizer of the ''[[Májovci]]'' literary group. During this time, Arbes was persecuted and spent 15 months in the Czech Lipa prison, for leading opposition to the ruling [[Austro-Hungarian Empire]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Slovník českých spisovatelů |editor-first1=Věra |editor-last1=Menclová |editor-first2=Václav |editor-last2=Vaněk |year=2005 |publisher=Libri |location=[[Prague]] |isbn=80-7277-179-5 |page=52 |language=cs}}</ref> He left Prague soon after, spending time in Paris and the South of France as part of the intellectual community there. In France, he was an associate of other "Bohemian Parisiens" such as [[Paul Alexis]], [[Luděk Marold]], [[Guy de Maupassant]], [[Viktor Oliva]], and [[Karel Vítězslav Mašek]], as well as the French writer [[Émile François Zola]]. |

||

== Writer == |

== Writer == |

||

Arbes |

Arbes worked with contemporary writers including [[Jiří Karásek ze Lvovic]], [[Josef Svatopluk Machar]] and his mentor [[Jan Neruda]], and was influenced by the English-language writers [[Lord Byron]] and [[Edgar Allan Poe]]. He translated many of Poe's writings into French and Czech, and named his son Edgar. Arbes was also strongly influenced by [[Émile Zola]]'s theory of the experimental novel.<ref name="culik"/> Arbes wrote about the urban working classes and promoted his ideas of utopian socialism.<ref name="culik"/> His work incorporates the themes of moral justice, [[free-thinker|free thinking]] and [[rationalism]],<ref name="culik"/> and also featured autobiographical elements.<ref name="culik"/> His characters were often creative and rebellious free-thinkers, whose intellectual abilities made them independent, but were eventually destroyed by non-conformism.<ref name="culik"/> |

||

His most well-known works are his "romanettoes", written in the 1860s and the 1870s, predecessors of the modern detective story. They are mostly set in Central Europe, and they usually feature a gothic mystery, which is resolved by logical reasoning. Arbes's "romanettoes" introduced technical knowledge and scientific reasoning into modern literature.<ref name="culik">{{cite web|url=http://www.arts.gla.ac.uk/Slavonic/Cz_novel.html |title=The Czech Noval |first=Jan |last=Čulík |author-link=Jan Čulík |access-date=1 May 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120124015743/http://www.arts.gla.ac.uk/Slavonic/Cz_novel.html |archive-date=24 January 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

== Newton's Brain == |

=== ''Newton's Brain'' === |

||

Among Arbes's most influential works was 'Newton's |

Among Arbes's most influential works was ''Newton's Brain'' (1877). In this story, two ideas coincide: the brain of the genius and trickster, apparently dies at the [[Battle of Königgrätz]] in the [[Austro-Prussian War]] of 1866. However, he has not died and instead is able to procure a replacement for his injured brain, which is the brain of [[Isaac Newton]]. Subsequently, he uses Newton's knowledge of the laws of nature to overcome them, using a strange device to travel faster than the speed of light, and also to photograph the past. In the end, the narrator's friend discloses to the audience that this device is human imagination. However, it is a very precise instrument and can be used to reconstruct the truth of history, in this case the Battle of Königgrätz. ''Newton's Brain'' was published 18 years before [[H. G. Wells]]'s ''[[The Time Machine]]'', and has been considered a strong influence on Wells. [[Émile Zola|Zola]] wrote that Arbes "is not a poet, not an artist, but rather a writer, and one of considerable stature, by which I mean an intellectual experimenter, a mind of a certain intellectual partiality and from a specific social background, an author with a socially critical and ameliorative tendency, and an educator rather than a discoverer in spheres of soul and form".<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2W-QMbKoHMoC&q=jakub+arbes+wellsl&pg=PA169|title=The Reception of H.G. Wells in Europe|first1=Patrick|last1=Parrinder|first2=John S.|last2=Partington|date=12 July 2005|publisher=Bloomsbury Academic|isbn=9780826462534|via=Google Books}}</ref> |

||

== Legacy == |

== Legacy == |

||

A public square in central Prague is named in his honour, as well as several other squares and streets in Czech cities. |

|||

== Works == |

== Works == |

||

{{Wikisource author}} |

|||

=== Romanettos === |

=== Romanettos === |

||

| Line 23: | Line 56: | ||

*''Zázračná madona'' (1875) |

*''Zázračná madona'' (1875) |

||

*''Ukřižovaná'' (1876) |

*''Ukřižovaná'' (1876) |

||

*''Newtonův mozek'' |

*''Newtonův mozek'' [[''Newton's Brain'']] (1877) |

||

**''Newton's Brain'', trans. Josef Jiří Král, 1892; newly edited, Sublunary Editions, 2021 |

|||

*''Akrobati'' (1878) |

*''Akrobati'' (1878) |

||

*''Zborcené harfy tón'' (1885–1886) |

*''Zborcené harfy tón'' (1885–1886) |

||

| Line 53: | Line 87: | ||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons |

{{Commons}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Wikisource|Author:Jakub Arbes}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Jakub Arbes}} |

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Jakub Arbes}} |

||

| Line 60: | Line 96: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arbes, Jakub}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Arbes, Jakub}} |

||

[[Category:Czech male |

[[Category:Czech male journalists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Novelists from Austria-Hungary]] |

||

[[Category:Journalists from Austria-Hungary]] |

|||

[[Category:1840 births]] |

[[Category:1840 births]] |

||

[[Category:1914 deaths]] |

[[Category:1914 deaths]] |

||

Latest revision as of 23:41, 29 June 2024

Jakub Arbes | |

|---|---|

Jakub Arbes (1884) | |

| Born | 12 June 1840 Prague, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 8 April 1914 (aged 73) Prague, Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | Praha-Smíchov |

| Occupation | Writer and journalist |

| Language | Czech |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Partner | Josefina Rabochová |

| Signature | |

| |

Jakub Arbes (12 June 1840, in Prague (Smíchov) – 8 April 1914) was a Czech writer and intellectual. He is best known as the creator of the literary genre called romanetto and spent much of his professional life in France.

Life and Politics

[edit]A native of Smíchov in Prague, Arbes studied under Jan Neruda, for whom he had a lifelong admiration, and later he studied Philosophy and Literature at Prague Polytechnic. In 1867, he began his career in journalism as editor of Vesna Kutnohorská, and from 1868 to 1877, as the chief editor of the National Press. Arbes was also an editor of political magazines Hlas (The Voice) and Politiks (Politics), and a sympathizer of the Májovci literary group. During this time, Arbes was persecuted and spent 15 months in the Czech Lipa prison, for leading opposition to the ruling Austro-Hungarian Empire.[1] He left Prague soon after, spending time in Paris and the South of France as part of the intellectual community there. In France, he was an associate of other "Bohemian Parisiens" such as Paul Alexis, Luděk Marold, Guy de Maupassant, Viktor Oliva, and Karel Vítězslav Mašek, as well as the French writer Émile François Zola.

Writer

[edit]Arbes worked with contemporary writers including Jiří Karásek ze Lvovic, Josef Svatopluk Machar and his mentor Jan Neruda, and was influenced by the English-language writers Lord Byron and Edgar Allan Poe. He translated many of Poe's writings into French and Czech, and named his son Edgar. Arbes was also strongly influenced by Émile Zola's theory of the experimental novel.[2] Arbes wrote about the urban working classes and promoted his ideas of utopian socialism.[2] His work incorporates the themes of moral justice, free thinking and rationalism,[2] and also featured autobiographical elements.[2] His characters were often creative and rebellious free-thinkers, whose intellectual abilities made them independent, but were eventually destroyed by non-conformism.[2]

His most well-known works are his "romanettoes", written in the 1860s and the 1870s, predecessors of the modern detective story. They are mostly set in Central Europe, and they usually feature a gothic mystery, which is resolved by logical reasoning. Arbes's "romanettoes" introduced technical knowledge and scientific reasoning into modern literature.[2]

Newton's Brain

[edit]Among Arbes's most influential works was Newton's Brain (1877). In this story, two ideas coincide: the brain of the genius and trickster, apparently dies at the Battle of Königgrätz in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. However, he has not died and instead is able to procure a replacement for his injured brain, which is the brain of Isaac Newton. Subsequently, he uses Newton's knowledge of the laws of nature to overcome them, using a strange device to travel faster than the speed of light, and also to photograph the past. In the end, the narrator's friend discloses to the audience that this device is human imagination. However, it is a very precise instrument and can be used to reconstruct the truth of history, in this case the Battle of Königgrätz. Newton's Brain was published 18 years before H. G. Wells's The Time Machine, and has been considered a strong influence on Wells. Zola wrote that Arbes "is not a poet, not an artist, but rather a writer, and one of considerable stature, by which I mean an intellectual experimenter, a mind of a certain intellectual partiality and from a specific social background, an author with a socially critical and ameliorative tendency, and an educator rather than a discoverer in spheres of soul and form".[3]

Legacy

[edit]A public square in central Prague is named in his honour, as well as several other squares and streets in Czech cities.

Works

[edit]Romanettos

[edit]- Ďábel na skřipci (1865)

- Elegie o černých očích (1865–1867)

- Svatý Xaverius (1873)

- Sivooký démon (1873)

- Zázračná madona (1875)

- Ukřižovaná (1876)

- Newtonův mozek ''Newton's Brain'' (1877)

- Newton's Brain, trans. Josef Jiří Král, 1892; newly edited, Sublunary Editions, 2021

- Akrobati (1878)

- Zborcené harfy tón (1885–1886)

- Lotr Gólo (1886)

- Duhový bod nad hlavou (1889)

- Duhokřídlá Psýché (1891)

- Kandidáti existence

- Etiopská lilie

Novels

[edit]- Moderní upíři

- Štrajchpudlíci

- Mesiáš

- Anděl míru

- Kandidáti existence

- Český Paganini

- Záhadné povahy

- Z duševní dílny básníků

Journalism

[edit]- Epizody

- Pláč koruny české neboli Nová persekuce

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Menclová, Věra; Vaněk, Václav, eds. (2005). Slovník českých spisovatelů (in Czech). Prague: Libri. p. 52. ISBN 80-7277-179-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Čulík, Jan. "The Czech Noval". Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick; Partington, John S. (12 July 2005). The Reception of H.G. Wells in Europe. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9780826462534 – via Google Books.