Christmas in the American Civil War: Difference between revisions

→Celebrating: Correct title to avoid redirect |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|none}} <!-- This short description is INTENTIONALLY "none" - please see WP:SDNONE before you consider changing it! --> |

|||

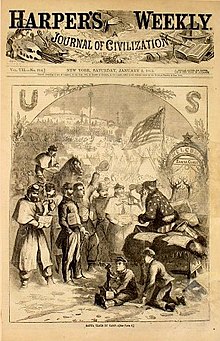

[[File:1863 harpers.jpg|thumb|Santa Claus distributes gifts to Union troops in [[Thomas Nast|Nast]]'s first Santa Claus [[cartoon]], (1863)]] |

[[File:1863 harpers.jpg|thumb|Santa Claus distributes gifts to Union troops in [[Thomas Nast|Nast]]'s first Santa Claus [[cartoon]], (1863)]] |

||

'''Christmas in the |

'''The process of Christmas''' becoming a national holiday in the U.S. began when Representative Burton Chauncey Cook of Illinois introduced a bill in the U.S. Congress after the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). It passed in both houses of Congress, and President Ulysses S. Grant signed it on June 28, 1870. During the Civil War, Christmas was celebrated in the [[Confederate States of America]] (the South). However, people doing non-religious celebrations were frowned upon and actually fined in Massachusetts. It was also seen as an unnecessary expense. It was thought to be a day of prayer and fasting by the Puritans and Lutherans. The day did not become an official holiday until five years after the war ended. The war continued to rage on Christmas, and skirmishes occurred throughout the countryside. Celebrations for both troops and civilians saw significant alteration. [[propaganda|Propagandists]], such as [[Thomas Nast]], used wartime Christmases to reflect their beliefs during the war. |

||

The day did not become an official holiday until five years after the war ended. The war continued to rage on Christmas and skirmishes occurred throughout the countryside. Celebrations for both troops and civilians saw significant alteration. [[propaganda|Propagandists]], such as [[Thomas Nast]], used wartime Christmases to reflect their beliefs. In 1870, Christmas became an official Federal holiday when President [[Ulysses S. Grant]] made it so in an attempt to unite north and south. |

|||

==War activities== |

==War activities== |

||

On the first Christmas Day during the war, Lincoln hosted a Christmas party during the evening; earlier that day, he spent many hours |

On the first Christmas Day during the war, Lincoln hosted a Christmas party during the evening; earlier that day, he spent many hours explaining the capture of Confederate representatives to [[Great Britain]] and [[France]], [[John Slidell]] and [[James Murray Mason]] (the [[Trent Affair]]).<ref name="Long p.151">Long p.151</ref> |

||

[[File:A&TLincoln.jpg|thumb|left|U.S. President [[Abraham Lincoln]] and his son [[Tad Lincoln|Thomas "Tad" Lincoln]]]] |

[[File:A&TLincoln.jpg|thumb|left|U.S. President [[Abraham Lincoln]] and his son [[Tad Lincoln|Thomas "Tad" Lincoln]]]] |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

In 1862, the Lincolns visited injured soldiers at the various hospitals.<ref name="Long p.301">Long p.301</ref> Many Union soldiers in 1863 received gifts "From [[Tad Lincoln]]", as Tad had been deeply moved by the plight of Union soldiers when he was taken by his father to see them. The gifts were mostly books and clothing.<ref>[https://www.hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/WHChristmas/lincoln/index.html Toy Soldier Tree] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171006194724/https://hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/WHChristmas/lincoln/index.html |date=2017-10-06 }} [[Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum]]</ref> The most famous Christmas gift Lincoln ever received came on December 22, 1864, when [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] announced the capture of [[Savannah, Georgia|Savannah]], Georgia.<ref name="Long p.615">Long p.615</ref> |

In 1862, the Lincolns visited injured soldiers at the various hospitals.<ref name="Long p.301">Long p.301</ref> Many Union soldiers in 1863 received gifts "From [[Tad Lincoln]]", as Tad had been deeply moved by the plight of Union soldiers when he was taken by his father to see them. The gifts were mostly books and clothing.<ref>[https://www.hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/WHChristmas/lincoln/index.html Toy Soldier Tree] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171006194724/https://hoover.archives.gov/exhibits/WHChristmas/lincoln/index.html |date=2017-10-06 }} [[Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum]]</ref> The most famous Christmas gift Lincoln ever received came on December 22, 1864, when [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] announced the capture of [[Savannah, Georgia|Savannah]], Georgia.<ref name="Long p.615">Long p.615</ref> |

||

Military exercises also took place on December 25. In 1861, a blockade runner was caught by the Union navy, and there were two skirmishes in Virginia and Maryland.<ref name="Long p.151"/> In 1862, there were several skirmishes, and Confederate general [[John Hunt Morgan]] engaged in his famous [[Morgan's Christmas Raid|Christmas Raid]] in Kentucky. On that day, Morgan's men destroyed everything they could of the improvements that the [[Louisville & Nashville Railroad]] had made along 35 miles of track from [[Bacon Creek (Kentucky)|Bacon Creek]] to [[Lebanon Junction, Kentucky|Lebanon Junction]].<ref name="Long p.301"/><ref>Herr p.37</ref> |

Military exercises also took place on December 25. In 1861, a blockade runner was caught by the Union navy, and there were two skirmishes in Virginia and Maryland.<ref name="Long p.151"/> In 1862, there were several skirmishes, and Confederate general [[John Hunt Morgan]] engaged in his famous [[Morgan's Christmas Raid|Christmas Raid]] in Kentucky. On that day, Morgan's men destroyed everything they could of the improvements that the [[Louisville & Nashville Railroad]] had made along 35 miles of track from [[Bacon Creek (Kentucky)|Bacon Creek]] to [[Lebanon Junction, Kentucky|Lebanon Junction]].<ref name="Long p.301"/><ref>Herr p.37</ref> There was also a military execution for desertion that the soldiers were forced to witness.<ref name="oha.alexandriava.gov">[http://oha.alexandriava.gov/fortward/special-sections/christmas/ "Ought it not be a Merry Christmas?"] Fort Ward Museum</ref> In 1863, Union forces destroyed [[Salt in the American Civil War|Confederate salt works]] at [[Bear Inlet, North Carolina|Bear Inlet]], North Carolina and, in South Carolina, there were skirmishes between the Union navy and Confederate artillery on the [[Stono River]] and near [[Charleston, South Carolina|Charleston]].<ref>Long p.449</ref> In 1864, the Confederates fiercely repelled the Federal assault of sixty warships on [[Fort Fisher]] and several skirmishes were fought in the western theater of the war.<ref name="Long p.615"/> |

||

==Celebrating== |

==Celebrating== |

||

[[File:Greeting Card Christmas c1860.jpg|thumb|A silk Christmas card, ca. 1860]] |

[[File:Greeting Card Christmas c1860.jpg|thumb|A silk Christmas card, ca. 1860]] |

||

Soldiers not actively campaigning celebrated Christmas in several ways. Union soldiers would use [[salt pork]] and [[hardtack]] to decorate [[Christmas tree]]s.<ref>[http://civilwarstudies.org/articles/Vol_4/xmas2001.htm Christmas North and South] CivilWarStudies.org</ref> |

Soldiers not actively campaigning celebrated Christmas in several ways. Union soldiers would use [[salt pork]] and [[hardtack]] to decorate [[Christmas tree]]s.<ref>[http://civilwarstudies.org/articles/Vol_4/xmas2001.htm Christmas North and South] CivilWarStudies.org</ref> Others were treated to special meals; a captain from Massachusetts treated his soldiers to foods such as turkey, [[oyster]]s, pies, and apples.<ref name="oha.alexandriava.gov"/> However, many soldiers received no special treats or privileges. In one incident on December 25, 1864, 90 Union soldiers from [[Michigan]], led by their captain, dispensed "food and supplies" to poor Georgians, with the [[mule]]s pulling the carts decorated to resemble [[reindeer]] by having tree branches tied to their heads.<ref name="oha.alexandriava.gov"/> In some units, celebrating Christmas was not allowed. On December 25, 1862, soldiers of one unit were punished for celebratory gunfire for the holiday, when actually the gunfire was for a funeral salute.<ref name="oha.alexandriava.gov"/> |

||

Carols, hymns, and seasonal songs were sung during the period, with some, such as "[[Deck the Halls]]", "[[Oh Come All Ye Faithful]]", and [[Felix Mendelssohn|Mendelssohn]]'s "[[Hark, the Herald Angels Sing]]" (1840), still sung today. American musical contributions to the season include "[[It Came Upon the Midnight Clear]]" (1850), "[[Jingle Bells]]" (1857), "[[We Three Kings of Orient Are]]" (1857) and "[[Up on the Housetop]]" (1860). Although popular in Europe at the time, [[Christmas card]]s were scarce in the United States, and would not enjoy widespread use until the 1870s.<ref>Collins, p.56</ref> |

Carols, hymns, and seasonal songs were sung during the period, with some, such as "[[Deck the Halls]]", "[[Oh Come All Ye Faithful]]", and [[Felix Mendelssohn|Mendelssohn]]'s "[[Hark, the Herald Angels Sing]]" (1840), still sung today. American musical contributions to the season include "[[It Came Upon the Midnight Clear]]" (1850), "[[Jingle Bells]]" (1857), "[[We Three Kings of Orient Are]]" (1857) and "[[Up on the Housetop]]" (1860). Although popular in Europe at the time, [[Christmas card]]s were scarce in the United States, and would not enjoy widespread use until the 1870s.<ref>Collins, p.56</ref> |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

[[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow]] wrote his pacifist poem, "Christmas Bells" on Christmas Day 1864<ref name="Gale">{{cite book | last=Gale | first=Robert L. | title=A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion | location=Westport, Connecticut | publisher=Greenwood Press | year=2003 | page=28 | isbn=0-313-32350-X}}</ref> at the news of his son Lieutenant Charles Appleton Longfellow having suffered severe wounds in November during the Mine Run Campaign. The poem was set to the tune "Waltham" by John Baptiste Calkin sometime after 1872 and has since been received into the established library of Christmas carols as "[[I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day]]". The carol version does not include two stanzas from the original poem that focused on the war.<ref>Griffin, Pam. [http://www.thedestinlog.com/articles/songs_7358___article.html/christmas_culture.html The songs of Christmas spread the real meaning of season] ''The Destin Log'', December 18, 2008</ref><ref>Studwell pp.166-7</ref> |

[[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow]] wrote his pacifist poem, "Christmas Bells" on Christmas Day 1864<ref name="Gale">{{cite book | last=Gale | first=Robert L. | title=A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion | location=Westport, Connecticut | publisher=Greenwood Press | year=2003 | page=28 | isbn=0-313-32350-X}}</ref> at the news of his son Lieutenant Charles Appleton Longfellow having suffered severe wounds in November during the Mine Run Campaign. The poem was set to the tune "Waltham" by John Baptiste Calkin sometime after 1872 and has since been received into the established library of Christmas carols as "[[I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day]]". The carol version does not include two stanzas from the original poem that focused on the war.<ref>Griffin, Pam. [http://www.thedestinlog.com/articles/songs_7358___article.html/christmas_culture.html The songs of Christmas spread the real meaning of season] ''The Destin Log'', December 18, 2008</ref><ref>Studwell pp.166-7</ref> |

||

For children, Christmas was altered during the war. Presents were fewer, especially in the devastated South. In ''We Were Marching on Christmas Day'', author Kevin Rawlings notes that some southern children worried about the Union blockade, and one little girl, [[Sallie Brock Putnam]], plotted the course Santa Claus would have to take to avoid it. Sometimes fathers on both sides were allowed [[furlough]], and children were said to react to their fathers as if seeing "near strangers".<ref name="Marten p.120">Marten p.120</ref> |

For children, Christmas was altered during the war. Presents were fewer, especially in the devastated South. In ''We Were Marching on Christmas Day'', author Kevin Rawlings notes that some southern children worried about the Union blockade, and one little girl, [[Sallie Brock Putnam]], plotted the course Santa Claus would have to take to avoid it. Sometimes fathers on both sides were allowed [[furlough]], and children were said to react to their fathers as if seeing "near strangers".<ref name="Marten p.120">Marten p.120</ref> Excuses for a lack of Santa included Yankees having shot him.<ref name="Marten p.120" /> |

||

==Nast cartoons and other propaganda== |

==Nast cartoons and other propaganda== |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

[[Thomas Nast]], who used his editorial cartoons to issue Union propaganda,<ref>Lively, James. '''Propaganda Techniques of Civil War Cartoonists''' ''The Public Opinion Quarterly'', Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring, 1942)</ref> made several illustrations reflecting the war. |

[[Thomas Nast]], who used his editorial cartoons to issue Union propaganda,<ref>Lively, James. '''Propaganda Techniques of Civil War Cartoonists''' ''The Public Opinion Quarterly'', Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring, 1942)</ref> made several illustrations reflecting the war. |

||

The one for Christmas Eve 1862, which ran in the January 1863 issue of [[Harper's Weekly]] shows a wife on one side praying though a window in one circle, and in another circle shows her husband on the battlefield, also in prayer.<ref>[http://www.sonofthesouth.net/Civil_War_Christmas.htm Thomas Nast's Original "Civil War Christmas" Print] Sonofthesouth.net</ref> |

The one for Christmas Eve 1862, which ran in the January 1863 issue of [[Harper's Weekly]] shows a wife on one side praying though a window in one circle, and in another circle shows her husband on the battlefield, also in prayer.<ref>[http://www.sonofthesouth.net/Civil_War_Christmas.htm Thomas Nast's Original "Civil War Christmas" Print] Sonofthesouth.net</ref> The same issue's cover started how Santa Claus would be perceived by future Americans, as a white-bearded Santa hands such gifts as socks to Union soldiers, while also holding a [[Jefferson Davis]] dancing puppet with a rope tied around its neck to imply his execution.<ref>[http://www.sonofthesouth.net/Original_Santa_Claus_.htm Thomas Nast's Original Civil War "Santa Claus In Camp" Print] Sonofthesouth.net</ref> The Christmas 1863 issue showed the couple back together.<ref>[http://www.historynet.com/christmas-in-the-civil-war-december-1998-civil-war-times-feature.htm/2 Christmas in the Civil War] Historynet.com</ref> |

||

[[File:Thomas Nast illustration of Abraham Lincoln welcoming Confederates to Christmas dinner, Christmas 1864.jpg|thumb|left|Lincoln welcomes Confederate soldiers (Nast, 1864)]] |

[[File:Thomas Nast illustration of Abraham Lincoln welcoming Confederates to Christmas dinner, Christmas 1864.jpg|thumb|left|Lincoln welcomes Confederate soldiers (Nast, 1864)]] |

||

The Nast Christmas cartoon for 1864 was a more conciliatory piece, showing Lincoln inviting Confederate soldiers into a warm lodge hall full of merriment.<ref>[http://www.sonofthesouth.net/nast_Union_Christmas.htm Thomas Nast's Original "The Union Christmas" Civil War Print] Sonofthesouth.net</ref> |

The Nast Christmas cartoon for 1864 was a more conciliatory piece, showing Lincoln inviting Confederate soldiers into a warm lodge hall full of merriment.<ref>[http://www.sonofthesouth.net/nast_Union_Christmas.htm Thomas Nast's Original "The Union Christmas" Civil War Print] Sonofthesouth.net</ref> Lincoln called Nast's use of Santa Claus "the best recruiting sergeant the North ever had".<ref name="oha.alexandriava.gov"/> |

||

Nast was not the only one to use Christmas as a propaganda tool. On the Union side, ''[[The New York Herald]]'' also engaged in propaganda. One illustration published in the paper included [[Santa Claus]] fuming that he could not reach southern children, due to the northern blockade.<ref name="Marten p.120"/> |

Nast was not the only one to use Christmas as a propaganda tool. On the Union side, ''[[The New York Herald]]'' also engaged in propaganda. One illustration published in the paper included [[Santa Claus]] fuming that he could not reach southern children, due to the northern blockade.<ref name="Marten p.120"/> On the Confederate side, ''The Richmond Examiner'' described Santa to its young readers as "a [[Dutch (ethnic group)|Dutch]] toy monger" who was a New York/New England "scrub" and Hottentot that had nothing to do with traditional [[Virginia]]n celebrations of Christmas.<ref name="Marten p.120"/> |

||

Even through the war was over, Nast had a drawing in the Christmas 1865 issue of Harper's Weekly depicting the heads of several Confederate generals at [[Ulysses S. Grant]]'s feet in an image that centered on Santa.<ref>[http://www.historynet.com/christmas-in-the-civil-war-december-1998-civil-war-times-feature.htm/5 Christmas in the Civil War] Historynet.com</ref> |

Even through the war was over, Nast had a drawing in the Christmas 1865 issue of Harper's Weekly depicting the heads of several Confederate generals at [[Ulysses S. Grant]]'s feet in an image that centered on Santa.<ref>[http://www.historynet.com/christmas-in-the-civil-war-december-1998-civil-war-times-feature.htm/5 Christmas in the Civil War] Historynet.com</ref> After the war Nast purposely made the [[North Pole]] the home of Saint Nick so that no one else could use him for nationalistic propaganda like Nast himself did.<ref>[http://www.historynet.com/christmas-in-the-civil-war-december-1998-civil-war-times-feature.htm Christmas in the Civil War] Historynet.com</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| author = Herr, Kincaid A. |

| author = Herr, Kincaid A. |

||

| title = |

| title = The Louisville & Nashville Railroad, 1850–1963 |

||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| publisher = University Press of Kentucky |

| publisher = University Press of Kentucky |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| author = Long, E.B. |

| author = Long, E.B. |

||

| title = |

| title = The Civil War day by day; an almanac, 1861–1865 |

||

| url = https://archive.org/details/civilwardaybyday00eblo |

| url = https://archive.org/details/civilwardaybyday00eblo |

||

| url-access = registration |

| url-access = registration |

||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| author = Marten, James |

| author = Marten, James |

||

| title = |

| title = The Children's Civil War |

||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| publisher = University of North Carolina Press |

| publisher = University of North Carolina Press |

||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| author = Rawlings, Kevin |

| author = Rawlings, Kevin |

||

| title = |

| title = We Were Marching on Christmas Day |

||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| publisher = Toomey Pr |

| publisher = Toomey Pr |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

*{{cite book |

*{{cite book |

||

| author = Studwell, William Emmett |

| author = Studwell, William Emmett |

||

| title = |

| title = The Christmas Carol Reader |

||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| publisher = Haworth Press |

| publisher = Haworth Press |

||

Latest revision as of 14:53, 31 July 2024

The process of Christmas becoming a national holiday in the U.S. began when Representative Burton Chauncey Cook of Illinois introduced a bill in the U.S. Congress after the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). It passed in both houses of Congress, and President Ulysses S. Grant signed it on June 28, 1870. During the Civil War, Christmas was celebrated in the Confederate States of America (the South). However, people doing non-religious celebrations were frowned upon and actually fined in Massachusetts. It was also seen as an unnecessary expense. It was thought to be a day of prayer and fasting by the Puritans and Lutherans. The day did not become an official holiday until five years after the war ended. The war continued to rage on Christmas, and skirmishes occurred throughout the countryside. Celebrations for both troops and civilians saw significant alteration. Propagandists, such as Thomas Nast, used wartime Christmases to reflect their beliefs during the war.

War activities

[edit]On the first Christmas Day during the war, Lincoln hosted a Christmas party during the evening; earlier that day, he spent many hours explaining the capture of Confederate representatives to Great Britain and France, John Slidell and James Murray Mason (the Trent Affair).[1]

In 1862, the Lincolns visited injured soldiers at the various hospitals.[2] Many Union soldiers in 1863 received gifts "From Tad Lincoln", as Tad had been deeply moved by the plight of Union soldiers when he was taken by his father to see them. The gifts were mostly books and clothing.[3] The most famous Christmas gift Lincoln ever received came on December 22, 1864, when William Tecumseh Sherman announced the capture of Savannah, Georgia.[4]

Military exercises also took place on December 25. In 1861, a blockade runner was caught by the Union navy, and there were two skirmishes in Virginia and Maryland.[1] In 1862, there were several skirmishes, and Confederate general John Hunt Morgan engaged in his famous Christmas Raid in Kentucky. On that day, Morgan's men destroyed everything they could of the improvements that the Louisville & Nashville Railroad had made along 35 miles of track from Bacon Creek to Lebanon Junction.[2][5] There was also a military execution for desertion that the soldiers were forced to witness.[6] In 1863, Union forces destroyed Confederate salt works at Bear Inlet, North Carolina and, in South Carolina, there were skirmishes between the Union navy and Confederate artillery on the Stono River and near Charleston.[7] In 1864, the Confederates fiercely repelled the Federal assault of sixty warships on Fort Fisher and several skirmishes were fought in the western theater of the war.[4]

Celebrating

[edit]

Soldiers not actively campaigning celebrated Christmas in several ways. Union soldiers would use salt pork and hardtack to decorate Christmas trees.[8] Others were treated to special meals; a captain from Massachusetts treated his soldiers to foods such as turkey, oysters, pies, and apples.[6] However, many soldiers received no special treats or privileges. In one incident on December 25, 1864, 90 Union soldiers from Michigan, led by their captain, dispensed "food and supplies" to poor Georgians, with the mules pulling the carts decorated to resemble reindeer by having tree branches tied to their heads.[6] In some units, celebrating Christmas was not allowed. On December 25, 1862, soldiers of one unit were punished for celebratory gunfire for the holiday, when actually the gunfire was for a funeral salute.[6]

Carols, hymns, and seasonal songs were sung during the period, with some, such as "Deck the Halls", "Oh Come All Ye Faithful", and Mendelssohn's "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing" (1840), still sung today. American musical contributions to the season include "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear" (1850), "Jingle Bells" (1857), "We Three Kings of Orient Are" (1857) and "Up on the Housetop" (1860). Although popular in Europe at the time, Christmas cards were scarce in the United States, and would not enjoy widespread use until the 1870s.[9]

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote his pacifist poem, "Christmas Bells" on Christmas Day 1864[10] at the news of his son Lieutenant Charles Appleton Longfellow having suffered severe wounds in November during the Mine Run Campaign. The poem was set to the tune "Waltham" by John Baptiste Calkin sometime after 1872 and has since been received into the established library of Christmas carols as "I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day". The carol version does not include two stanzas from the original poem that focused on the war.[11][12]

For children, Christmas was altered during the war. Presents were fewer, especially in the devastated South. In We Were Marching on Christmas Day, author Kevin Rawlings notes that some southern children worried about the Union blockade, and one little girl, Sallie Brock Putnam, plotted the course Santa Claus would have to take to avoid it. Sometimes fathers on both sides were allowed furlough, and children were said to react to their fathers as if seeing "near strangers".[13] Excuses for a lack of Santa included Yankees having shot him.[13]

Nast cartoons and other propaganda

[edit]

Thomas Nast, who used his editorial cartoons to issue Union propaganda,[14] made several illustrations reflecting the war.

The one for Christmas Eve 1862, which ran in the January 1863 issue of Harper's Weekly shows a wife on one side praying though a window in one circle, and in another circle shows her husband on the battlefield, also in prayer.[15] The same issue's cover started how Santa Claus would be perceived by future Americans, as a white-bearded Santa hands such gifts as socks to Union soldiers, while also holding a Jefferson Davis dancing puppet with a rope tied around its neck to imply his execution.[16] The Christmas 1863 issue showed the couple back together.[17]

The Nast Christmas cartoon for 1864 was a more conciliatory piece, showing Lincoln inviting Confederate soldiers into a warm lodge hall full of merriment.[18] Lincoln called Nast's use of Santa Claus "the best recruiting sergeant the North ever had".[6]

Nast was not the only one to use Christmas as a propaganda tool. On the Union side, The New York Herald also engaged in propaganda. One illustration published in the paper included Santa Claus fuming that he could not reach southern children, due to the northern blockade.[13] On the Confederate side, The Richmond Examiner described Santa to its young readers as "a Dutch toy monger" who was a New York/New England "scrub" and Hottentot that had nothing to do with traditional Virginian celebrations of Christmas.[13]

Even through the war was over, Nast had a drawing in the Christmas 1865 issue of Harper's Weekly depicting the heads of several Confederate generals at Ulysses S. Grant's feet in an image that centered on Santa.[19] After the war Nast purposely made the North Pole the home of Saint Nick so that no one else could use him for nationalistic propaganda like Nast himself did.[20]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Long p.151

- ^ a b Long p.301

- ^ Toy Soldier Tree Archived 2017-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum

- ^ a b Long p.615

- ^ Herr p.37

- ^ a b c d e "Ought it not be a Merry Christmas?" Fort Ward Museum

- ^ Long p.449

- ^ Christmas North and South CivilWarStudies.org

- ^ Collins, p.56

- ^ Gale, Robert L. (2003). A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-313-32350-X.

- ^ Griffin, Pam. The songs of Christmas spread the real meaning of season The Destin Log, December 18, 2008

- ^ Studwell pp.166-7

- ^ a b c d Marten p.120

- ^ Lively, James. Propaganda Techniques of Civil War Cartoonists The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring, 1942)

- ^ Thomas Nast's Original "Civil War Christmas" Print Sonofthesouth.net

- ^ Thomas Nast's Original Civil War "Santa Claus In Camp" Print Sonofthesouth.net

- ^ Christmas in the Civil War Historynet.com

- ^ Thomas Nast's Original "The Union Christmas" Civil War Print Sonofthesouth.net

- ^ Christmas in the Civil War Historynet.com

- ^ Christmas in the Civil War Historynet.com

References

[edit]- Collins, Ace (2003). Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Zondervan. ISBN 0-310-24880-9.

- Herr, Kincaid A. (2000). The Louisville & Nashville Railroad, 1850–1963. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2184-1.

- Long, E.B. (1971). The Civil War day by day; an almanac, 1861–1865. Doubleday. ISBN 0-306-80255-4.

- Marten, James (2000). The Children's Civil War. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4904-9.

- Rawlings, Kevin (1997). We Were Marching on Christmas Day. Toomey Pr. ISBN 0-9612670-6-2.

- Studwell, William Emmett (1995). The Christmas Carol Reader. Haworth Press. ISBN 1-56023-872-0.