Force field (physics): Difference between revisions

m Bot: link specificity and minor changes |

No edit summary Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

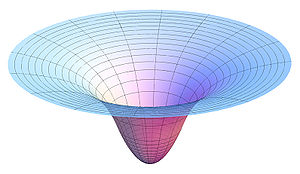

[[Image:GravityPotential.jpg|thumb|300px|Plot of a two-dimensional slice of the gravitational potential in and around a uniform spherical body. The [[inflection point]]s of the cross-section are at the surface of the body.]] |

[[Image:GravityPotential.jpg|thumb|300px|Plot of a two-dimensional slice of the gravitational potential in and around a uniform spherical body. The [[inflection point]]s of the cross-section are at the surface of the body.]] |

||

In [[physics]] a '''force field''' is a [[vector field]] |

In [[physics]], a '''force field''' is a [[vector field]] corresponding with a [[non-contact force]] acting on a particle at various positions in [[space]]. Specifically, a force field is a vector field <math>\mathbf F</math>, where <math>\mathbf F(\mathbf r)</math> is the force that a particle would feel if it were at the position <math>\mathbf r</math>.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=akbi_iLSMa4C&pg=PA211 Mathematical methods in chemical engineering, by V. G. Jenson and G. V. Jeffreys, p211]</ref> |

||

==Examples== |

==Examples== |

||

*[[Gravity]] is the force of attraction between two objects. A gravitational force field models this influence that a massive body (or more generally, any quantity of [[Mass–energy equivalence|energy]]) extends into the space around itself.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*A gravitational force field is a model used to explain the influence that a massive body extends into the space around itself, producing a force on another massive body.,<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|title=General relativity from A to B |

|title=General relativity from A to B |

||

|first1=Robert |

|first1=Robert |

||

| Line 17: | Line 15: | ||

|isbn=0-226-28864-1 |

|isbn=0-226-28864-1 |

||

|page=181 |

|page=181 |

||

| ⚫ | |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UkxPpqHs0RkC&pg=PA181}}, [https://books.google.com/books?id=UkxPpqHs0RkC&pg=PA181 Chapter 7, page 181] </ref> In [[Newtonian gravity]], a particle of mass ''M'' creates a [[gravitational field]] <math>\mathbf g=\frac{-G M}{r^2}\hat\mathbf r</math>, where the radial [[unit vector]] <math>\hat\mathbf r</math> points away from the particle. The gravitational force experienced by a particle of light mass ''m'', close to the surface of [[Earth]] is given by <math>\mathbf F = m \mathbf g</math>, where ''g'' is [[Earth's gravity]].<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=LiRLJf2m_dwC&pg=PA288 Vector calculus, by Marsden and Tromba, p288]</ref><ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=bCP68dm49OkC&pg=PA104 Engineering mechanics, by Kumar, p104]</ref> |

||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UkxPpqHs0RkC&pg=PA181}}, [https://books.google.com/books?id=UkxPpqHs0RkC&pg=PA181 Chapter 7, page 181] </ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*In a [[magnetic field]] <math>\mathbf B</math>, a point charge moving through it experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the direction of the field, following the relation: <math>\mathbf F = q\mathbf v\times\mathbf B</math>. |

|||

== Work == |

== Work == |

||

As a particle moves through a force field along a path ''C'', the [[Work (physics)|work]] done by the force is a [[line integral]] |

Work is dependent on the displacement as well as the force acting on an object. As a particle moves through a force field along a path ''C'', the [[Work (physics)|work]] done by the force is a [[line integral]]: |

||

:<math> W = \int_C \ |

:<math> W = \int_C \mathbf F \cdot d\mathbf r</math> |

||

This value is independent of the [[velocity]][[Momentum|/momentum]] that the particle travels along the path. |

This value is independent of the [[velocity]][[Momentum|/momentum]] that the particle travels along the path. |

||

=== Conservative force field === |

=== Conservative force field === |

||

For a [[conservative force|conservative force field]], it is also independent of the path itself, depending only on the starting and ending points. Therefore, |

For a [[conservative force|conservative force field]], it is also independent of the path itself, depending only on the starting and ending points. Therefore, the work for an object travelling in a closed path is zero, since its starting and ending points are the same: |

||

:<math> \oint_C \ |

:<math> \oint_C \mathbf F \cdot d\mathbf r = 0</math> |

||

If the field is conservative, the work done can be more easily evaluated by realizing that a conservative vector field can be written as the gradient of some scalar potential function: |

If the field is conservative, the work done can be more easily evaluated by realizing that a conservative vector field can be written as the gradient of some scalar potential function: |

||

:<math> \ |

:<math> \mathbf F = -\nabla \phi</math> |

||

The work done is then simply the difference in the value of this potential in the starting and end points of the path. If these points are given by ''x'' = ''a'' and ''x'' = ''b'', respectively: |

The work done is then simply the difference in the value of this potential in the starting and end points of the path. If these points are given by ''x'' = ''a'' and ''x'' = ''b'', respectively: |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Classical mechanics]] |

|||

* [[Field line]] |

* [[Field line]] |

||

* [[Force]] |

* [[Force]] |

||

* [[Work (physics)|Mechanical work]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 48: | Line 50: | ||

* [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/301/lectures/node59.html Conservative and non-conservative force-fields], [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/301/lectures/lectures.html Classical Mechanics], University of Texas at Austin |

* [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/301/lectures/node59.html Conservative and non-conservative force-fields], [http://farside.ph.utexas.edu/teaching/301/lectures/lectures.html Classical Mechanics], University of Texas at Austin |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Force Field (Physics)}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Classicalmechanics-stub}} |

|||

{{Electromagnetism-stub}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Latest revision as of 08:19, 14 August 2024

In physics, a force field is a vector field corresponding with a non-contact force acting on a particle at various positions in space. Specifically, a force field is a vector field , where is the force that a particle would feel if it were at the position .[1]

Examples

[edit]- Gravity is the force of attraction between two objects. A gravitational force field models this influence that a massive body (or more generally, any quantity of energy) extends into the space around itself.[2] In Newtonian gravity, a particle of mass M creates a gravitational field , where the radial unit vector points away from the particle. The gravitational force experienced by a particle of light mass m, close to the surface of Earth is given by , where g is Earth's gravity.[3][4]

- An electric field exerts a force on a point charge q, given by .[5]

- In a magnetic field , a point charge moving through it experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the direction of the field, following the relation: .

Work

[edit]Work is dependent on the displacement as well as the force acting on an object. As a particle moves through a force field along a path C, the work done by the force is a line integral:

This value is independent of the velocity/momentum that the particle travels along the path.

Conservative force field

[edit]For a conservative force field, it is also independent of the path itself, depending only on the starting and ending points. Therefore, the work for an object travelling in a closed path is zero, since its starting and ending points are the same:

If the field is conservative, the work done can be more easily evaluated by realizing that a conservative vector field can be written as the gradient of some scalar potential function:

The work done is then simply the difference in the value of this potential in the starting and end points of the path. If these points are given by x = a and x = b, respectively:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mathematical methods in chemical engineering, by V. G. Jenson and G. V. Jeffreys, p211

- ^ Geroch, Robert (1981). General relativity from A to B. University of Chicago Press. p. 181. ISBN 0-226-28864-1., Chapter 7, page 181

- ^ Vector calculus, by Marsden and Tromba, p288

- ^ Engineering mechanics, by Kumar, p104

- ^ Calculus: Early Transcendental Functions, by Larson, Hostetler, Edwards, p1055

External links

[edit]- Conservative and non-conservative force-fields, Classical Mechanics, University of Texas at Austin