Principles of Model Checking: Difference between revisions

create; meets WP:NBOOK#1 |

m Disambiguating links to Deadlock (link changed to Deadlock (computer science)) using DisamAssist. |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Infobox book |

{{Infobox book |

||

| name = Principles of Model Checking |

| name = Principles of Model Checking |

||

| image = |

| image = Principles of Model Checking.jpg |

||

| alt = |

| alt = Principles of Model Checking |

||

| caption = |

| caption = Front cover |

||

| author = [[Christel Baier]] and [[Joost-Pieter Katoen]] |

| author = [[Christel Baier]] and [[Joost-Pieter Katoen]] |

||

| subject = [[Model checking]] |

| subject = [[Model checking]] |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

[[File: |

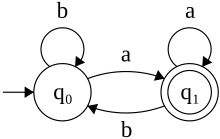

[[File:2-state Buchi automaton.svg|thumb|alt=Buchi automaton|An example [[transition system]] used to model a process]] |

||

The introduction and first chapter outline the field of [[model checking]]: a model of a machine or process can be analysed to see if desirable properties hold. For instance, a [[vending machine]] might satisfy the property "the balance can never fall below €0,00". A video game might enforce the rule "if the player has 0 lives then the game ends in a loss". Both the vending machine and video game can be modelled as [[transition system]]s. Model checking is the process of describing such requirements in mathematical language, and automating proofs that the model satisfies the requirements, or discovery of [[counterexample]]s if the model is faulty. |

The introduction and first chapter outline the field of [[model checking]]: a model of a machine or process can be analysed to see if desirable properties hold. For instance, a [[vending machine]] might satisfy the property "the balance can never fall below €0,00". A video game might enforce the rule "if the player has 0 lives then the game ends in a loss". Both the vending machine and video game can be modelled as [[transition system]]s. Model checking is the process of describing such requirements in mathematical language, and automating proofs that the model satisfies the requirements, or discovery of [[counterexample]]s if the model is faulty. |

||

The second chapter focuses on creating an appropriate model for [[concurrency (computer science)|concurrent systems]], where multiple parts of an [[algorithm]] (set of instructions) can be carried out simultaneously by different machines or parts of a machine. |

The second chapter focuses on creating an appropriate model for [[concurrency (computer science)|concurrent systems]], where multiple parts of an [[algorithm]] (set of instructions) can be carried out simultaneously by different machines or parts of a machine. |

||

Chapters 3 explores types of rules that a transition system may satisfy: [[linear time properties]]. A [[safety property]], such as "no [[deadlock]] states are possible", is of the form "an undesirable outcome can never occur". A [[liveness]] property, such as "a shared resource will always eventually be made available to a component that requests it", is of the form "a desirable outcome will eventually happen". Fairness properties such as "a traffic light never stops changing colour" can be used as [[precondition]]s i.e. assumptions from which other properties can be deduced. |

Chapters 3 explores types of rules that a transition system may satisfy: [[linear time properties]]. A [[safety property]], such as "no [[Deadlock (computer science)|deadlock]] states are possible", is of the form "an undesirable outcome can never occur". A [[liveness]] property, such as "a shared resource will always eventually be made available to a component that requests it", is of the form "a desirable outcome will eventually happen". Fairness properties such as "a traffic light never stops changing colour" can be used as [[precondition]]s i.e. assumptions from which other properties can be deduced. |

||

The fourth chapter is about [[regular language|regular]] and [[Omega-regular language|ω-regular]] language properties, and theoretical machines such as [[Büchi automata]] that model the languages. It gives model |

The fourth chapter is about [[regular language|regular]] and [[Omega-regular language|ω-regular]] language properties, and theoretical machines such as [[Büchi automata]] that model the languages. It gives model-checking algorithms to verify properties or find counterexamples. |

||

The fifth and sixth chapters explore [[linear temporal logic]] (LTL) and [[computation tree logic]] (CTL), two classes of formula that express properties. LTL encodes requirements about paths through a system, such as "every [[Monopoly (game)|Monopoly]] player passes 'Go' infinitely often"; CTL encodes requirements about states in a system, such as "from any position, all players can eventually land on 'Go'". [[CTL*]] formulae, which combine the two grammars, are also defined. Algorithms for model |

The fifth and sixth chapters explore [[linear temporal logic]] (LTL) and [[computation tree logic]] (CTL), two classes of formula that express properties. LTL encodes requirements about paths through a system, such as "every [[Monopoly (game)|Monopoly]] player passes 'Go' infinitely often"; CTL encodes requirements about states in a system, such as "from any position, all players can eventually land on 'Go'". [[CTL*]] formulae, which combine the two grammars, are also defined. Algorithms for model-checking formulae in these logics are given. |

||

The seventh chapter explores formal ways to compare transition systems, such as [[bisimulation]]; the eighth is about [[partial order reduction]]s that aim to reduce the computation required to verify properties of a model. The ninth and tenth chapters are about extensions to the logics and automata previously considered, including through addition of a clock speed ([[timed automata]]) or probabilities ([[probabilistic automata]], based on [[Markov chain]]s). |

The seventh chapter explores formal ways to compare transition systems, such as [[bisimulation]]; the eighth is about [[partial order reduction]]s that aim to reduce the computation required to verify properties of a model. The ninth and tenth chapters are about extensions to the logics and automata previously considered, including through addition of a clock speed ([[timed automata]]) or probabilities ([[probabilistic automata]], based on [[Markov chain]]s). |

||

==Reception== |

==Reception== |

||

François Laroussinie, writing in ''[[The Computer Journal]]'', recommended the book to researchers, lecturers, students and engineers, calling the book "impressive". Laroussinie found the textbook comprehensive and accessibly written, with a good number of examples, exercises and motivating ideas for key concepts. With a "unified framework", the first seven chapters cover classical theory and the last three chapters cover extensions of model checking.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Principles of Model Checking (Review)|journal=[[The Computer Journal]]|last=Laroussinie|first=François|year=2010|volume=53|issue=5| |

François Laroussinie, writing in ''[[The Computer Journal]]'', recommended the book to researchers, lecturers, students and engineers, calling the book "impressive". Laroussinie found the textbook comprehensive and accessibly written, with a good number of examples, exercises and motivating ideas for key concepts. With a "unified framework", the first seven chapters cover classical theory and the last three chapters cover extensions of model checking.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Principles of Model Checking (Review)|journal=[[The Computer Journal]]|last=Laroussinie|first=François|year=2010|volume=53|issue=5|pages=615–616|doi=10.1093/comjnl/bxp025}}</ref> |

||

In ''[[ACM Computing Reviews]]'', Gabriel Ciobanu believed the textbook could be used in advanced undergraduate or graduate courses, and would be useful to researchers. Ciobanu praised the "clear and intuitive" presentation and said it "should be appreciated for its pedagogical approach to covering basic concepts, deep theoretical results, and advanced topics in model checking research".<ref name="ACM">{{cite journal|title=Principles of Model Checking (Review)|journal=[[ACM Computing Reviews]]|url=https://www.computingreviews.com/review/review_review.cfm?review_id=136406|last=Ciobanu|first=Gabriel|date=8 January 2009}}</ref> |

In ''[[ACM Computing Reviews]]'', Gabriel Ciobanu believed the textbook could be used in advanced undergraduate or graduate courses, and would be useful to researchers. Ciobanu praised the "clear and intuitive" presentation and said it "should be appreciated for its pedagogical approach to covering basic concepts, deep theoretical results, and advanced topics in model checking research".<ref name="ACM">{{cite journal|title=Principles of Model Checking (Review)|journal=[[ACM Computing Reviews]]|url=https://www.computingreviews.com/review/review_review.cfm?review_id=136406|last=Ciobanu|first=Gabriel|date=8 January 2009}}</ref> |

||

In 2014, the book was one of the five most-cited academic texts monitored by the [[Book Citation Index]] (BKCI).<ref>{{cite journal|title=Can Amazon.com Reviews Help to Assess the Wider Impacts of Books?|journal=[[Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology]]| |

In 2014, the book was one of the five most-cited academic texts monitored by the [[Book Citation Index]] (BKCI).<ref>{{cite journal|title=Can Amazon.com Reviews Help to Assess the Wider Impacts of Books?|journal=[[Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology]]|last1=Kousha|first1=Kayvan|last2=Thelwall|first2=Mike|date=1 March 2016|page=580}}</ref> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

*{{citation|last=Lange|first=Martin|title=none|journal=[[MathSciNet]]|year=2010|mr=2493187}} |

*{{citation|last=Lange|first=Martin|title=none|journal=[[MathSciNet]]|year=2010|mr=2493187}} |

||

==External links== |

|||

* [https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262026499/principles-of-model-checking/ Official website] |

|||

[[Category:2008 non-fiction books]] |

[[Category:2008 non-fiction books]] |

||

[[Category:Computer science |

[[Category:Computer science textbooks]] |

||

[[Category:Textbooks]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 21:30, 20 August 2024

Front cover | |

| Author | Christel Baier and Joost-Pieter Katoen |

|---|---|

| Subject | Model checking |

| Publisher | MIT Press |

Publication date | 25 April 2008 |

| Pages | 975 |

| ISBN | 9780262026499 |

Principles of Model Checking is a textbook on model checking, an area of computer science that automates the problem of determining if a machine meets specification requirements. It was written by Christel Baier and Joost-Pieter Katoen, and published in 2008 by MIT Press.

Synopsis

[edit]

The introduction and first chapter outline the field of model checking: a model of a machine or process can be analysed to see if desirable properties hold. For instance, a vending machine might satisfy the property "the balance can never fall below €0,00". A video game might enforce the rule "if the player has 0 lives then the game ends in a loss". Both the vending machine and video game can be modelled as transition systems. Model checking is the process of describing such requirements in mathematical language, and automating proofs that the model satisfies the requirements, or discovery of counterexamples if the model is faulty.

The second chapter focuses on creating an appropriate model for concurrent systems, where multiple parts of an algorithm (set of instructions) can be carried out simultaneously by different machines or parts of a machine.

Chapters 3 explores types of rules that a transition system may satisfy: linear time properties. A safety property, such as "no deadlock states are possible", is of the form "an undesirable outcome can never occur". A liveness property, such as "a shared resource will always eventually be made available to a component that requests it", is of the form "a desirable outcome will eventually happen". Fairness properties such as "a traffic light never stops changing colour" can be used as preconditions i.e. assumptions from which other properties can be deduced.

The fourth chapter is about regular and ω-regular language properties, and theoretical machines such as Büchi automata that model the languages. It gives model-checking algorithms to verify properties or find counterexamples.

The fifth and sixth chapters explore linear temporal logic (LTL) and computation tree logic (CTL), two classes of formula that express properties. LTL encodes requirements about paths through a system, such as "every Monopoly player passes 'Go' infinitely often"; CTL encodes requirements about states in a system, such as "from any position, all players can eventually land on 'Go'". CTL* formulae, which combine the two grammars, are also defined. Algorithms for model-checking formulae in these logics are given.

The seventh chapter explores formal ways to compare transition systems, such as bisimulation; the eighth is about partial order reductions that aim to reduce the computation required to verify properties of a model. The ninth and tenth chapters are about extensions to the logics and automata previously considered, including through addition of a clock speed (timed automata) or probabilities (probabilistic automata, based on Markov chains).

Reception

[edit]François Laroussinie, writing in The Computer Journal, recommended the book to researchers, lecturers, students and engineers, calling the book "impressive". Laroussinie found the textbook comprehensive and accessibly written, with a good number of examples, exercises and motivating ideas for key concepts. With a "unified framework", the first seven chapters cover classical theory and the last three chapters cover extensions of model checking.[1]

In ACM Computing Reviews, Gabriel Ciobanu believed the textbook could be used in advanced undergraduate or graduate courses, and would be useful to researchers. Ciobanu praised the "clear and intuitive" presentation and said it "should be appreciated for its pedagogical approach to covering basic concepts, deep theoretical results, and advanced topics in model checking research".[2]

In 2014, the book was one of the five most-cited academic texts monitored by the Book Citation Index (BKCI).[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Laroussinie, François (2010). "Principles of Model Checking (Review)". The Computer Journal. 53 (5): 615–616. doi:10.1093/comjnl/bxp025.

- ^ Ciobanu, Gabriel (8 January 2009). "Principles of Model Checking (Review)". ACM Computing Reviews.

- ^ Kousha, Kayvan; Thelwall, Mike (1 March 2016). "Can Amazon.com Reviews Help to Assess the Wider Impacts of Books?". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology: 580.

Further reading

[edit]- Lange, Martin (2010), MathSciNet, MR 2493187

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)