Gallium monoiodide: Difference between revisions

→Synthesis: wikipedia isn't a manual |

stoopid jittery mouse. Sorry about that misclick! Undid revision 1241600445 by DMacks (talk) |

||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{research paper|date=November 2023}} |

|||

{{Chembox |

{{Chembox |

||

<!-- Images --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ImageFile = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ImageSize = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ImageAlt = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<!-- Names --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| IUPACName = |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| |

| OtherNames = |

||

<!-- Sections --> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| SMILES = [Ga]I |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| Section2 = {{Chembox Properties |

|||

| Formula = GaI |

|||

| MolarMass = 196.63 g/mol |

|||

| Appearance = Pale green solid |

|||

| Density = |

|||

| MeltingPt = |

|||

| BoilingPt = |

|||

| Solubility = Hydrolysis |

|||

}} |

|||

| Section3 = {{Chembox Hazards |

|||

| MainHazards = |

|||

| FlashPt = |

|||

| AutoignitionPt = |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Gallium monoiodide''' |

'''Gallium monoiodide''' is an inorganic [[gallium]] compound with the formula '''GaI''' or Ga<sub>4</sub>I<sub>4</sub>. It is a pale green solid and mixed valent gallium compound, which can contain gallium in the 0, +1, +2, and +3 oxidation states. It is used as a pathway for many gallium-based products. Unlike the [[Gallium halides|gallium(I) halides]] first crystallographically characterized,<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last1=Dohmeier|first1=Carsten|last2=Loos|first2=Dagmar|last3=Schnöckel|first3=Hansgeorg|date=1996|title=Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Compounds: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactions|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/anie.199601291|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English|language=en|volume=35|issue=2|pages=129–149|doi=10.1002/anie.199601291|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> gallium monoiodide has a more facile synthesis allowing a synthetic route to many low-valent gallium compounds. |

||

== |

==Synthesis== |

||

[[ |

In 1990, [[Malcolm Green (chemist)|Malcolm Green]] synthesized gallium monoiodide by the [[Sonication|ultrasonication]] of liquid gallium metal with [[iodine]] in [[toluene]] yielding a pale green powder referred to as gallium monoiodide.<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal|last1=Green|first1=Malcolm L. H.|last2=Mountford|first2=Philip|last3=Smout|first3=Geoffrey J.|last4=Speel|first4=S. Robert|date=1990-01-01|title=New synthetic pathways into the organometallic chemistry of gallium|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277538700868096|journal=Polyhedron|language=en|volume=9|issue=22|pages=2763–2765|doi=10.1016/S0277-5387(00)86809-6|issn=0277-5387}}</ref> The chemical composition of gallium monoiodide was not determined until the early to mid-2010s despite its simple synthesis. |

||

In 2012, the pale green |

In 2012, the pale green gallium monoiodide was determined to be a combination of gallium metal and [[gallium(I,III) iodide]], having the chemical composition [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>].<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last1=Widdifield|first1=Cory M.|last2=Jurca|first2=Titel|last3=Richeson|first3=Darrin S.|last4=Bryce|first4=David L.|date=2012-03-16|title=Using 69/71Ga solid-state NMR and 127I NQR as probes to elucidate the composition of "GaI"|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277538712000101|journal=Polyhedron|language=en|volume=35|issue=1|pages=96–100|doi=10.1016/j.poly.2012.01.003|issn=0277-5387}}</ref> However, in 2014, it was found that the incomplete reaction of gallium metal with iodine yielded gallium monoiodide with this chemical composition. Gallium monoiodide synthesized with longer reaction times for complete reaction had a different chemical composition [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>].<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last1=Malbrecht|first1=Brian J.|last2=Dube|first2=Jonathan W.|last3=Willans|first3=Mathew J.|last4=Ragogna|first4=Paul J.|date=2014-09-15|title=Addressing the Chemical Sorcery of "GaI": Benefits of Solid-State Analysis Aiding in the Synthesis of P→Ga Coordination Compounds|url=https://doi.org/10.1021/ic501139w|journal=Inorganic Chemistry|volume=53|issue=18|pages=9644–9656|doi=10.1021/ic501139w|pmid=25184621|issn=0020-1669}}</ref> |

||

The resultant gallium monoiodide is highly air sensitive, but stable under inert atmosphere conditions for up to a year at -35 ˚C.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

== |

==Characterization== |

||

When gallium monoiodide was first produced, it was proposed that gallium monoiodide is a combination of gallium metal, Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>3</sub> and Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>4</sub> based on the characteristic [[Raman spectroscopy|Raman spectra]] of these constituents.<ref name=":3">{{Cite journal|last1=Wilkinson|first1=M.|last2=Worrall|first2=I. J.|date=1975-07-01|title=Synthesis of alkylgallium diiodides|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022328X00941421|journal=Journal of Organometallic Chemistry|language=en|volume=93|issue=1|pages=39–42|doi=10.1016/S0022-328X(00)94142-1|issn=0022-328X}}</ref> |

|||

This hypothesis was confirmed as two variants of gallium monoiodide were determined to have the chemical compositions [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>], simplified as Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>4</sub>·2Ga, and [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>], simplified as Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>3</sub>·Ga.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | When the incompletely reacted product was probed by [[NMR spectroscopy]], it showed the presence gallium metal.<ref name=":1" /> When probed by <sup>127</sup>I [[Nuclear quadrupole resonance|NQR]],<ref name=":4" /> it showed the presence of Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>4</sub> and further confirms the [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] assignment.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Okuda|first1=Tsutomu|last2=Hamamoto|first2=Hiroshi|last3=Ishihara|first3=Hideta|last4=Negita|first4=Hisao|date=1985-09-01|title=79Br and 127I Nuclear Quadrupole Resonance of Mixed Valency Compounds Ga2X4(X=Br, I)|journal=Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan|volume=58|issue=9|pages=2731–2732|doi=10.1246/bcsj.58.2731|issn=0009-2673|doi-access=free}}</ref> Raman spectroscopy has also confirmed this composition assignment.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5">{{Cite journal|last1=Beamish|first1=J. C.|last2=Wilkinson|first2=M.|last3=Worrall|first3=I. J.|date=1978-07-01|title=Facile synthesis of the lower valent halides of gallium, Ga2X4 (X = chloride, bromide, iodide) and tetragallium hexaiodide|url=https://doi.org/10.1021/ic50185a069|journal=Inorganic Chemistry|volume=17|issue=7|pages=2026–2027|doi=10.1021/ic50185a069|issn=0020-1669}}</ref> All of the evidence from other spectroscopic methods, and [[Powder diffraction|power x-ray diffraction]] patterns, validates the assignment of [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] for the incompletely reacted gallium monoiodide variant. |

||

=== [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] === |

|||

| ⚫ | When |

||

| ⚫ | When the completely reacted product was probed by <sup>127</sup>I NQR, it showed the presence of Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>3</sub>.<ref name=":4" /> Raman spectroscopy has also confirmed this assignment, as it aligned with those from a Ga<sub>4</sub>I<sub>6</sub> reference.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /> Finally, power x-ray diffraction supports that this gallium monoiodide variant matches that of characteristic Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>3,</sub> which is different from that of GaI<sub>2</sub>.<ref name=":4" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | When probed by <sup>127</sup>I NQR, |

||

| ⚫ | |||

=== <sup>69/71</sup>Ga SSNMR of "GaI" === |

|||

There have been some conflicting reports in interpreting the <sup>69/71</sup>Ga [[Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance|solid-state NMR]] spectra of the two "GaI" variants. One interpretation is that a signal at δ<sub>iso</sub> = -424(5) ppm with a non-zero QI tensor is characteristic of a distorted tetrahedral [GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] constituent.<ref name=":1" /> Thus, this spectra would defend a [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] assignment. However, another finding shows that this signal at δ<sub>iso</sub> = -425(3) is seen in conjunction with another peak at δ<sub>iso</sub> = 15(5) ppm. In this case, the peak at δ<sub>iso</sub> = -425(3) could correspond to Ga<sup>+</sup> as seen within GaI<sub>2</sub>, and δ<sub>iso</sub> = 15(5) ppm could correspond to [Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>].<ref name=":4" /> Thus, this spectra could also defend a [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>] assignment. These differing interpretations suggest that <sup>69/71</sup>Ga solid-state NMR alone will not be able to conclusively assign a specific chemical composition to a "GaI" variant. <sup>69/71</sup>Ga solid-state NMR should be analyzed in conjunction with other spectroscopic measurements to make these assignments robust. |

|||

==Reactions and derivatives== |

|||

It is important to note that because [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>][GaI<sub>4</sub><sup>−</sup>] can convert to [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>] over time<ref name=":4" /> the chemical composition of "GaI" should be verified for products that can only be accessed with one "GaI" variant. |

|||

| ⚫ | Gallium monoiodide is used as a precursor for a variety of reactions, acting as a [[lewis acid]] and a [[reducing agent]]. Early-on, gallium monoiodide was shown to produce alkylgallium diiodides via oxidative addition by reacting liquid gallium metal and iodine in the presence of an alkyl iodide.<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":6">{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Jones|first2=Cameron|date=2005-04-11|title="GaI": A versatile reagent for the synthetic chemist|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2005/dt/b501310k|journal=Dalton Transactions|language=en|issue=8|pages=1341–1348|doi=10.1039/B501310K|pmid=15824768|hdl=2262/69572|issn=1477-9234|hdl-access=free}}</ref> Since then, other [[Organogallium chemistry|organogallium complexes]] have been synthesized, as well as [[Lewis acids and bases|Lewis base]] adducts and gallium based clusters.<ref name=":6" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== Reactivity == |

|||

| ⚫ | [[File:GaI Lewis base adduct.png|thumb|Reaction pathways of various gallium monoiodide Lewis base adducts. Reactions were conducted in toluene at - 78 ˚C.<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Bettentrup|first2=Helga|last3=Jones|first3=Cameron|date=2003|title=The Reactivity of Primary and Secondary Amines, Secondary Phosphanes and N-Heterocyclic Carbenes towards Group-13 Metal(I) Halides|url=https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejic.200300068|journal=European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry|language=en|volume=2003|issue=13|pages=2446–2451|doi=10.1002/ejic.200300068|issn=1099-0682}}</ref> (L = phosphines, ethers, amines).<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":7" />]] |

||

| ⚫ | Gallium monoiodide reacts with various monodentate [[Lewis acids and bases|Lewis bases]] to form Ga(II), Ga(III), or mixed valent compounds, as well as gallium-based dimers and trimers. For example, gallium monoiodide can react with primary, secondary, and tertiary [[amines]], secondary or tertiary [[phosphines]] or [[ethers]] to form Ga(II)-Ga(II) dimers.<ref name=":2" /><ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8">{{Cite journal|last1=Schnepf|first1=Andreas|last2=Doriat|first2=Clemens|date=1997-01-01|title=A simple synthesis for donor-stabilized Ga2I4 and Ga3I5 species and the X-ray crystal structure of Ga3I5·3PEt3|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/1997/cc/a703776g|journal=Chemical Communications|language=en|issue=21|pages=2111–2112|doi=10.1039/A703776G|issn=1364-548X}}</ref> Gallium monoiodide can also react with [[triphenylphosphine]] (PPh<sub>3</sub>) to form Ga(III)I<sub>3</sub>PPh<sub>3</sub>.<ref name=":2" /> It also reacts with the less sterically hindered [[triethylphosphine]] (PEt<sub>3</sub>) to form a Ga(II)-Ga(I)-Ga(II) mixed valent complex with datively coordinated PEt<sub>3</sub> ligands.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8" /> These reactions are believed to be a [[disproportionation]], as gallium metal is produced in these reactions.<ref name=":7" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Gallium monoiodide reacts with [[triphenylstibine]] to produce an SbPh<sub>3</sub> fragment datively bonded to a GaPhI<sub>2</sub> fragment.<ref name=":9">{{Cite journal|last1=Cameron Jones|last2=Christian Schulten|last3=Andreas Stasch|date=2005-04-01|title=[Gal2Ph(SbPh3)]: A Rare Tertiary Stibane-Gallium Complex Formed via a Reductive Sb-C Bond Cleavage Reaction|journal=Main Group Metal Chemistry|language=en|volume=28|issue=2|pages=89–92|doi=10.1515/MGMC.2005.28.2.89|s2cid=101459028|issn=0792-1241|doi-access=free}}</ref> The difference in reactivity between PPh<sub>3</sub> and SbPh<sub>3</sub>, a heavy atom analogue of PPh<sub>3</sub>, can be attributed to a weaker Sb-C bond, allowing for transfer of a phenyl group from antimony to gallium. This suggests that gallium monoiodide can be used as a reducing agent as well.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":9" /> |

||

While there is some discrepancy with how these different "GaI" variants are obtained (i.e. length of reaction, temperature of reaction, time of degradation), the fact that two different "GaI" variants can be accessed provides some insight into how such a wide range of reactivities can be accessed via "GaI". |

|||

[[File:SbPh3 datively bonded to GaPhI2.png|center|250px]] |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Persistent carbene|N-heterocyclic carbenes]] reacts with gallium monoiodide to form a complex with a sterically hindered [[isopropyl]] ligand.<ref name=":7" /> However, gallium monoiodide reacts with [[Diimine#1,2-Diimines|diazabutadienes]] and subsequent reduction by [[potassium]] metal to form Ga analogs of N-heterocyclic carbenes.<ref name=":6" /> Other Ga-based carbenes can be produced from gallium monoiodide precursor using Li([[NacNac]]).<ref name=":6" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Gallium monoiodide reacts with multidentate Lewis bases, such as [[bipyridine]], phenyl-terpyridine, and bis(imino)pyridine ligands to form Ga(III) complexes.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":10">{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Jones|first2=Cameron|last3=Kloth|first3=Marc|last4=Mills|first4=David P.|date=2004-02-03|title=The reactivity of gallium(I) and indium(I) halides towards bipyridines, terpyridines, imino-substituted pyridines and bis(imino)acenaphthenes|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2004/nj/b310592j|journal=New Journal of Chemistry|language=en|volume=28|issue=2|pages=207–213|doi=10.1039/B310592J|issn=1369-9261}}</ref> Crystallographically, the bipyridine derivative has a distorted octahedral geometry, with a Ga–N bond length of 2.063 Å. The phenyl-terpyridine derivative adopts a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry where the two equatorial Ga–N bonds (as drawn) are longer than the axial Ga-N bond, with 2.104 Å and 2.007(5) Å, respectively. The average Ga-N bond length (2.071 Å) is similar to that of a neutral GaCl<sub>3</sub>(terpy) Lewis base adduct (2.086 Å).<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Beran|first1=G.|last2=Carty|first2=A. J.|last3=Patel|first3=H. A.|last4=Palenik|first4=Gus J.|date=1970-01-01|title=A trans-effect in gallium complexes: the crystal structure of trichloro-(2,2′,2"-terpyridyl)gallium(III)|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/1970/c2/c29700000222|journal=Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications|language=en|issue=4|pages=222–223|doi=10.1039/C29700000222|issn=0577-6171}}</ref> The bis(imino)pyridine derivative has a distorted square-based pyramidal geometry. Like for the phenyl-terpyridine derivative, the equatorial imino Ga-N bonds (2.203 Å) are longer than the axial pyridyl Ga-N bond (2.014(7) A˚).<ref name=":10" /> Despite these similar reactivities and bond characteristics, when gallium monoiodide was reacted with imino-substituted pyridines (RN=C(H)Py), unique reactivity was observed. Reductive coupling of the imino-substituted pyridines formed diamido-digallium(III) complexes.<ref name=":10" /> These reactions display the ability of gallium monoiodides to form new [[Carbon–carbon bond|C-C bonds]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[File:GaI polydentate Lewis base adduct.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Reaction pathways with gallium monoiodide and polydentate Lewis bases form Ga(III) salts (R = Ar, Bu<sup>t</sup>; Ar = C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>3</sub>Pr<sup>i</sup><sub>2</sub>-2,6; Py = 2-pyridyl). Reactions were conducted in toluene at - 78 ˚C. Only the bis(imino)pyridine derivative was reacted at 25 ˚C. All complexes have been crystallographically characterized.<ref name=":10" />]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Gallium monoiodide can also be used as a precursor to form gallium-based heterocycles. Reactions with [[Diimine#1,2-Diimines|diazabutadienes]], {RN=C(H)}<sub>2</sub>, forms monomers or dimers based on the substituents on the diazabutadienes. More sterically hindered substituents such as [[tert-butyl]] have resulted in the formation of gallium(II) dimers, whereas reactions with alkyl or aryl substituted diazabutadienes have formed Ga(III) monomers.<ref name=":6" /> Gallium monoiodide can be reacted with phenyl-substituted 1,4-diazabuta-1,3-dienes to form a gallium heterocycle with a diazabutadiene monoanion.<ref name=":18">{{Cite journal|last1=Pott|first1=Thomas|last2=Jutzi|first2=Peter|last3=Kaim|first3=Wolfgang|last4=Schoeller|first4=Wolfgang W.|last5=Neumann|first5=Beate|last6=Stammler|first6=Anja|last7=Stammler|first7=Hans-Georg|last8=Wanner|first8=Matthias|date=July 2002|title=Reactivity of "GaI" TowardN-Substituted 1,4-Diazabuta-1,3-dienes: Synthesis and Characterization of Gallium Heterocycles Containing Paramagnetic Diazabutadiene Monoanions|url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/om0200510|journal=Organometallics|volume=21|issue=15|pages=3169–3172|doi=10.1021/om0200510|issn=0276-7333}}</ref> [[Electron paramagnetic resonance|EPR spectroscopy]] has revealed that the diazabutadiene fragment is a [[Paramagnetism|paramagnetic]] monoanionic species rather than an ene-diamido dianion or a neutral ligand.<ref name=":18" /> Thus, gallium monoiodide undergoes a [[disproportionation]] reaction to form a gallium(III) complex with deposition of a gallium metal.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":18" /> Upon further reaction with a 1,4-dilithiated diazabutadiene, this gallium heterocycle forms a new complex with the diazabutadiene monoanion fragment datively bonded to the gallium center and an ene-diamido dianion covalently bonded to the Ga center.<ref name=":18" /> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:GaI Lewis base adduct.png|thumb|Reaction pathways of various |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Ga heterocycles.png|center|thumb|600x600px|Ga heterocycles formed from the reaction of gallium monoiodide with 1,4-diazabuta-1,3-dienes. R = 2,6-dimethylphenyl; 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl; 2,6-diisopropylphenyl. For the 1,4-dilithiated diazabutadiene reagent, R = 2,6-dimethylphenyl.<ref name=":18" />]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | One very important reactivity of this gallium(III) heterocycle is its ability to access gallium analogues of [[Persistent carbene|N-heterocyclic carbenes]] upon reduction with potassium metal.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Farley|first2=Robert D.|last3=Jones|first3=Cameron|last4=Kloth|first4=Marc|last5=Murphy|first5=Damien M.|date=2002-10-03|title=The reactivity of diazabutadienes toward low oxidation state Group 13 iodides and the synthesis of a new gallium(I) carbene analogue|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2002/dt/b206605j|journal=Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions|language=en|issue=20|pages=3844–3850|doi=10.1039/B206605J|issn=1364-5447}}</ref> Although a gallium analogue of [[Persistent carbene|N-heterocyclic carbenes]] had been synthesized previously,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Schmidt|first1=Eva S.|last2=Jockisch|first2=Alexander|last3=Schmidbaur|first3=Hubert|date=1999-10-01|title=A Carbene Analogue with Low-Valent Gallium as a Heteroatom in a quasi-Aromatic Imidazolate Anion|url=https://doi.org/10.1021/ja9928780|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|volume=121|issue=41|pages=9758–9759|doi=10.1021/ja9928780|issn=0002-7863}}</ref> having access to heavier analogues of N-heterocylic carbenes from a synthetically more facile gallium monoiodide route has opened new avenues in coordination chemistry, such as access to new Ga-M bonds.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Jones|first2=Cameron|last3=Mills|first3=David P.|last4=Murphy|first4=Damien M.|last5=Hey-Hawkins|first5=Evamarie|last6=Wolf|first6=Robert|date=2006-12-14|title=The reactivity of gallium-(I), -(II) and -(III) heterocycles towards Group 15 substrates: attempts to prepare gallium–terminal pnictinidene complexes|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2006/dt/b511451a|journal=Dalton Transactions|language=en|issue=1|pages=64–72|doi=10.1039/B511451A|pmid=16357962|issn=1477-9234}}</ref><ref name=":19">{{Cite journal|last1=Baker|first1=Robert J.|last2=Jones|first2=Cameron|date=2005-09-01|title=The coordination chemistry and reactivity of group 13 metal(I) heterocycles|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010854504003261|journal=Coordination Chemistry Reviews|series=36th International Conference on Coordination Chemistry, Merida, Mexico, July 2004|language=en|volume=249|issue=17|pages=1857–1869|doi=10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.016|issn=0010-8545}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Jones|first1=Cameron|last2=Rose|first2=Richard P.|last3=Stasch|first3=Andreas|date=2007-07-10|title=Synthesis and characterisation of zinc gallyl complexes: First structural elucidations of Zn–Ga bonds|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2007/dt/b706402k|journal=Dalton Transactions|language=en|issue=28|pages=2997–2999|doi=10.1039/B706402K|pmid=17622416|issn=1477-9234}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:SbPh3 datively bonded to GaPhI2.png|center|thumb|Reaction of "GaI" and SbPh<sub>3</sub> yields a complex with the SbPh<sub>3</sub> ligand datively bonded to GaPhI<sub>2</sub>. Image adapted from Baker and coworkers.<ref name=":6" />]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[File:GaI polydentate Lewis base adduct.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Reaction pathways with |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[File:Ga heterocycles.png|center|thumb|600x600px|Ga heterocycles formed from the reaction of |

||

| ⚫ | One very important reactivity of this |

||

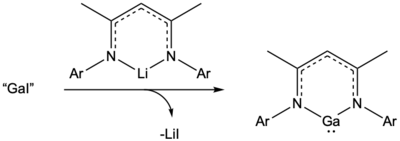

Gallium monoiodide can also be used to access six-membered gallium(I) heterocycles that have parallels to gallium analogues of N-heterocyclic carbenes. These neutral gallium(I) heterocycles can be synthesized by reacting gallium monoiodide and Li[nacnac].<ref name=":19" /><ref name=":20">{{Cite journal|last1=Hardman|first1=Ned J.|last2=Eichler|first2=Barrett E.|last3=Power|first3=Philip P.|date=2000-01-01|title=Synthesis and characterization of the monomer Ga{(NDippCMe)2CH} (Dipp = C6H3Pri2-2,6): a low valent gallium(I) carbene analogue|url=https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2000/cc/b005686n|journal=Chemical Communications|language=en|issue=20|pages=1991–1992|doi=10.1039/B005686N|issn=1364-548X}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Ga 6-member NHC new.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Reaction of |

[[File:Ga 6-member NHC new.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Reaction of gallium monoiodide (slurry) and Li[nacnac] in a dry ice/acetone bath to access a gallium(I) heterocycle. Excess potassium metal can be added to circumvent a Ga(II) derivative of the six-member gallium(I) heterocycle.<ref name=":20" /> Ar = Dipp.<ref name=":19" />]] |

||

===Cyclopentadienyl complexes=== |

|||

=== GaCp and GaCp* === |

|||

Gallium monoiodide can easily be converted to half-sandwich complexes, (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and cyclopentadienylgallium.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Loos|first1=Dagmar|last2=Baum|first2=Elke|last3=Ecker|first3=Achim|last4=Schnöckel|first4=Hansgeorg|last5=Downs|first5=Anthony J.|date=1997|title=Hexameric Aggregates in Crystalline (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) at 200 K|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/anie.199708601|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English|volume=36|issue=8|pages=860–862|doi=10.1002/anie.199708601|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) can be easily produced by reacting gallium monoiodide with a potassium salt of the desired ligand under toluene to avoid side products.<ref name=":14">{{Cite journal|last1=Jutzi|first1=Peter|last2=Schebaum|first2=Lars Oliver|date=2002-07-15|title=A novel synthetic route to pentaalkylcyclopentadienylgallium(I) compounds|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022328X02014298|journal=Journal of Organometallic Chemistry|language=en|volume=654|issue=1|pages=176–179|doi=10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01429-8|issn=0022-328X}}</ref><ref name=":6" /> |

|||

Cyclopentadienylgallium, which is less sterically hindered than (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), can also be accessed using a gallium monoiodide. This ligand can be synthesized with a [[Salt metathesis reaction|metathesis reaction]] of NaCp with gallium monoiodide.<ref name=":15">{{Cite journal|last1=Schenk|first1=Christian|last2=Köppe|first2=Ralf|last3=Schnöckel|first3=Hansgeorg|last4=Schnepf|first4=Andreas|date=2011|title=A Convenient Synthesis of Cyclopentadienylgallium – The Awakening of a Sleeping Beauty in Organometallic Chemistry|url=https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejic.201100672|journal=European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry|language=en|volume=2011|issue=25|pages=3681–3685|doi=10.1002/ejic.201100672|issn=1099-0682}}</ref> This cyclopentadienylgallium ligand has been used to access a GaCp<sub>2</sub>I complex with datively bonded cyclopentadienylgallium. This complex showcases an uncommon donor-acceptor Ga-Ga bond. Cyclopentadienylgallium can also be used to access a Lewis acid [[Tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane|B(C<sub>6</sub>F<sub>5</sub>)<sub>3</sub>]] complex with a datively bonded cyclopentadienylgallium ligand.<ref name=":15" /> For both of these two complexes, the (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) analogues have been synthesized and [[x-ray crystallography]] has supported that, as expected, (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) is a slightly stronger donor than cyclopentadienylgallium. |

|||

[[File:GaCp Chromium complex.png|thumb|GaCp reacts with Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>(cyclooctene) to form a new CpGa–Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>. The GaCp* analogue can also be accessed |

[[File:GaCp Chromium complex.png|thumb|GaCp reacts with Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>(cyclooctene) to form a new CpGa–Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>. The GaCp* analogue can also be accessed.<ref name=":16"/>]] |

||

Like |

Like (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), cyclopentadienylgallium can also coordinate to transition metal complexes such as Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>(cyclooctene) or Co<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>8</sub> to yield CpGa–Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub> or (thf)GaCp{Co(CO)<sub>4</sub>}<sub>2</sub>.<ref name=":16">{{Cite journal|last1=Naglav|first1=Dominik|last2=Tobey|first2=Briac|last3=Schnepf|first3=Andreas|date=2013|title=Application of GaCp as a Ligand in Coordination Chemistry: Similarities and Differences to GaCp*|url=https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejic.201300401|journal=European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry|language=en|volume=2013|issue=24|pages=4146–4149|doi=10.1002/ejic.201300401|issn=1099-0682}}</ref> For CpGa–Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>, the Ga-Cr bond length (239.6 pm) is similar to that for a (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) analogue (240.5 pm). For this complex, the [[trans effect]] is also observed, where the Cr-CO bond trans to the cyclopentadienylgallium ligand is contracted (186 pm) relative to the cis Cr-CO bonds (189.5 pm). While cyclopentadienylgallium can act as a terminal ligand similar to (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), it was determined that cyclopentadienylgallium analogues react faster than their (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) counterparts. This can be attributed to the lower steric bulk of cyclopentadienylgallium.<ref name=":16" /> |

||

Unlike reactivity with Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>(cyclooctene), reactivities of |

Unlike reactivity with Cr(CO)<sub>5</sub>(cyclooctene), reactivities of (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and cyclopentadienylgallium with Co<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>8</sub> diverge significantly.<ref name=":16" /> [[Dicobalt octacarbonyl]], or Co<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>8</sub>, exists in various isomeric states. One such isomer contains two bridging CO ligands. When (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) reacts with Co<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>8</sub>, two equivalents of CO gas are released, forming (CO)<sub>3</sub>Co[''μ''<sub>2</sub>-(''η''<sub>5</sub>-GaCp*)]<sub>2</sub>-Co(CO)<sub>3</sub>. This is a derivative of the [[dicobalt octacarbonyl]] complex where the bridging CO moieties are replaced by bridging (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) moieties.<ref name=":17">{{Cite journal|last1=Jutzi|first1=Peter|last2=Neumann|first2=Beate|last3=Reumann|first3=Guido|last4=Stammler|first4=Hans-Georg|date=1998-03-01|title=Pentamethylcyclopentadienylgallium (Cp*Ga): Alternative Synthesis and Application as a Terminal and Bridging Ligand in the Chemistry of Chromium, Iron, Cobalt, and Nickel|url=https://doi.org/10.1021/om970913a|journal=Organometallics|volume=17|issue=7|pages=1305–1314|doi=10.1021/om970913a|issn=0276-7333}}</ref> On the other hand, cyclopentadienylgallium enables oxidative addition to Co<sub>2</sub>(CO)<sub>8</sub> to form (thf)GaCp{Co(CO)<sub>4</sub>}<sub>2</sub>, where gallium has sigma interactions to two Co(CO)<sub>4</sub> units. The average Ga–Co bond length is 248.5 pm and gallium is in a formally +3 [[oxidation state]] in this new complex.<ref name=":17" /> Overall, straightforward synthesis of cyclopentadienylgallium from a gallium monoiodide precursor has many merits in expanding the scope of transition metal chemistry with lower valent species. |

||

=== |

===Gallium clusters=== |

||

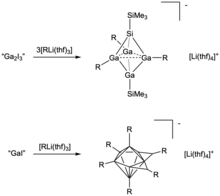

[[File:Ga clusters.png|thumb|Examples of Ga clusters synthesized from variants of |

[[File:Ga clusters.png|thumb|Examples of Ga clusters synthesized from variants of gallium monoiodide starting materials. R = Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>. For the [Ga<sub>9</sub>{Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>}<sub>6</sub><nowiki>]</nowiki><sup>−</sup> cluster, the polyhedral vertices are all Ga. Reactions were conducted in toluene at -78 ˚C.]] |

||

A variety of gallium clusters have also been synthesized from |

A variety of gallium clusters have also been synthesized from gallium monoiodide.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Schnepf|first1=Andreas|last2=Schnöckel|first2=Hansgeorg|date=2002|title=Metalloid Aluminum and Gallium Clusters: Element Modifications on the Molecular Scale?|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/1521-3773%2820021004%2941%3A19%3C3532%3A%3AAID-ANIE3532%3E3.0.CO%3B2-4|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition|language=en|volume=41|issue=19|pages=3532–3554|doi=10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3532::AID-ANIE3532>3.0.CO;2-4|pmid=12370894|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> These clusters have often been isolated as salts with bulky [[silyl]] or [[germyl]] anions, such as [Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>]<sup>−</sup>.<ref name=":6" /> An example of an isolated gallium cluster is [Ga<sub>9</sub>{Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>}<sub>6</sub>]<sup>−</sup>, which has a pentagonal bipyramidal polyhedral structure. It is synthesized by reacting gallium monoiodide with Li(thf)<sub>3</sub>Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub> in toluene at -78 ˚C.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":11">{{Cite journal|last1=Köstler|first1=Wolfgang|last2=Linti|first2=Gerald|date=1997|title=Synthesis and Structure of a Tetragallane [R4Ga4I3]− and a Polyhedral Nonagallane [R6Ga9]|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/anie.199726441|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English|volume=36|issue=23|pages=2644–2646|doi=10.1002/anie.199726441|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> This reaction has been shown to access a wide array of products, which may be attributed to the wide range of gallium monoiodide compositions that have been subsequently probed. Of these products, [Ga<sub>9</sub>{Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>}<sub>6</sub>]<sup>−</sup> is especially unique because Ga was found to have a very low average oxidation state (0.56) and also because this cluster has fewer R substituents than polyhedron vertices.<ref name=":11" /> Other clusters that been isolated via similar reaction pathways include [Ga<sub>10</sub>{Si(SiMe<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub>}<sub>6</sub>], which is a conjuncto-[[Polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory|polyhedral cluster]], and a closo-silatetragallane anion, which contains three 2-electron-2-center and three [[Three-center two-electron bond|2-electron-3-center bonds]].<ref name=":6" /><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Kehrwald|first1=Michael|last2=Köstler|first2=Wolfgang|last3=Rodig|first3=Alexander|last4=Linti|first4=Gerald|last5=Blank|first5=Thomas|last6=Wiberg|first6=Nils|date=2001-03-01|title=Ga10[Si(SiMe3)3]6, [Ga10(SitBu3)6]-, and [Ga13(SitBu3)6]-Syntheses and Structural Characterization of Novel Gallium Cluster Compounds|url=https://doi.org/10.1021/om000703p|journal=Organometallics|volume=20|issue=5|pages=860–867|doi=10.1021/om000703p|issn=0276-7333}}</ref><ref name=":12">{{Cite journal|last1=Linti|first1=Gerald|last2=Köstler|first2=Wolfgang|last3=Piotrowski|first3=Holger|last4=Rodig|first4=Alexander|date=1998|title=A Silatetragallane—Classical Heterobicyclopentane or closo-Polyhedron?|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/%28SICI%291521-3773%2819980904%2937%3A16%3C2209%3A%3AAID-ANIE2209%3E3.0.CO%3B2-3|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition|language=en|volume=37|issue=16|pages=2209–2211|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2209::AID-ANIE2209>3.0.CO;2-3|pmid=29711437|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> Interestingly, this latter species can only be synthesized when sub-stoichiometric quantities of I<sub>2</sub> are utilized to access a "Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>3</sub>" intermediate species.<ref name=":12" /> This is equivalent to reacting liquid gallium metal and iodine to pre-completion, which, as explained above, accesses the [Ga<sup>0</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sup>+</sup>]<sub>2</sub>[Ga<sub>2</sub>I<sub>6</sub><sup>2-</sup>] variant of gallium monoiodide. This highlights the versatility of the gallium monoiodide precursor in accessing a wide range of gallium-based complexes. |

||

[[File:Co GaI.png|thumb|Reaction of a diaryl Co(II) precursor with |

[[File:Co GaI.png|thumb|Reaction of a diaryl Co(II) precursor with gallium monoiodide yields a nido-type Co-GaI cluster. Ellipsoids set at 50% probability. Grey = carbon, blue = cobalt, pink = gallium, and magenta = iodine. Hydrogens not depicted. Image recreated using .cif file (deposited to The Cambridge Structural Database).<ref name=":21">{{Cite journal|last1=Blundell|first1=Toby J.|last2=Taylor|first2=Laurence J.|last3=Valentine|first3=Andrew J.|last4=Lewis|first4=William|last5=Blake|first5=Alexander J.|last6=McMaster|first6=Jonathan|last7=Kays|first7=Deborah L.|date=2020-07-21|title=A transition metal–gallium cluster formed via insertion of "GaI"|journal=Chemical Communications|language=en|volume=56|issue=58|pages=8139–8142|doi=10.1039/D0CC03559A|pmid=32691803|issn=1364-548X|doi-access=free}}</ref>]] |

||

Gallium monoiodide can also form cluster-type compounds with transition metals precursors. One example is the reaction between gallium monoiodide and (2,6-Pmp<sub>2</sub>C<sub>6</sub>H<sub>3</sub>)<sub>2</sub>Co, (Pmp = C<sub>6</sub>Me<sub>5</sub>), which yields a nido-type cluster.<ref name=":21" /> This molecule is structurally similar to [[cubane]], where the corners are metal and bridging iodine atoms, with one corner removed. This is a particularly unique Co-GaI cluster due to its unusual geometry for transition metal compounds containing heavy group 13 atoms such as gallium. The [[Atoms in molecules|bond critical points]] and bond paths, as computed with [[Atoms in molecules|QTAIM]] analysis, support that while there are Co-Ga bonds, there are no Ga-Ga bonds.<ref name=":21" /> |

|||

[[File:Co GaI cluster.png|center|thumb|300x300px|Bond critical points and bond paths of a Co-GaI cluster. |

[[File:Co GaI cluster.png|center|thumb|300x300px|Bond critical points and bond paths of a Co-GaI cluster.<ref name=":21" /> using Multiwfn 3.8 software.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Lu|first1=Tian|last2=Chen|first2=Feiwu|date=2012|title=Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jcc.22885|journal=Journal of Computational Chemistry|language=en|volume=33|issue=5|pages=580–592|doi=10.1002/jcc.22885|pmid=22162017|s2cid=13508697|issn=1096-987X}}</ref>]] |

||

Finally, |

Finally, gallium monoiodide has been able to form clusters with heavy gold atoms by acting as a reducing reagent when combined with (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and triphenylphosphine-gold complexes(i.e. AuI(PPh<sub>3</sub>) or AuCl(PPh<sub>3</sub>)).<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":13">{{Cite journal|last1=Anandhi|first1=U.|last2=Sharp|first2=Paul R.|date=2004|title=A Gallium-Coated Gold Cluster|url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/anie.200461295|journal=Angewandte Chemie International Edition|volume=43|issue=45|pages=6128–6131|doi=10.1002/anie.200461295|pmid=15549757|issn=1521-3773}}</ref> This cluster contained the first crystallographically confirmed Ga-Au bonds, consisting of a Au<sub>3</sub> cluster ligated by Ga ligands. In addition, [[natural bond orbital|NBO analysis]] showed that the charge on the galliums within the (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) ligands were much higher than the charge on the Au atoms and the charge on the gallium atoms within the GaI<sub>2</sub> motifs. This suggests that non-bridging Ga-Au bonds are highly polarized, whereas the μ-bridging Ga-Au bonds are more non-polar covalent in character.<ref name=":13" />[[File:Ga-Au cluster.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Ga-Au cluster formed by dropwise addition of LAuX to a mixture of GaCp*/"GaI" (excess) in dichloromethane.<ref name=":13" />]] |

||

== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Gallium(III) iodide]] |

* [[Gallium(III) iodide]] |

||

* [[Persistent carbene]] |

* [[Persistent carbene]] |

||

== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

Latest revision as of 03:33, 22 August 2024

This article is written like a research paper or scientific journal. (November 2023) |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| GaI | |

| Molar mass | 196.63 g/mol |

| Appearance | Pale green solid |

| Hydrolysis | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Gallium monoiodide is an inorganic gallium compound with the formula GaI or Ga4I4. It is a pale green solid and mixed valent gallium compound, which can contain gallium in the 0, +1, +2, and +3 oxidation states. It is used as a pathway for many gallium-based products. Unlike the gallium(I) halides first crystallographically characterized,[1] gallium monoiodide has a more facile synthesis allowing a synthetic route to many low-valent gallium compounds.

Synthesis

[edit]In 1990, Malcolm Green synthesized gallium monoiodide by the ultrasonication of liquid gallium metal with iodine in toluene yielding a pale green powder referred to as gallium monoiodide.[2] The chemical composition of gallium monoiodide was not determined until the early to mid-2010s despite its simple synthesis.

In 2012, the pale green gallium monoiodide was determined to be a combination of gallium metal and gallium(I,III) iodide, having the chemical composition [Ga0]2[Ga+][GaI4−].[3] However, in 2014, it was found that the incomplete reaction of gallium metal with iodine yielded gallium monoiodide with this chemical composition. Gallium monoiodide synthesized with longer reaction times for complete reaction had a different chemical composition [Ga0]2[Ga+]2[Ga2I62-].[4]

The resultant gallium monoiodide is highly air sensitive, but stable under inert atmosphere conditions for up to a year at -35 ˚C.[4]

Characterization

[edit]When gallium monoiodide was first produced, it was proposed that gallium monoiodide is a combination of gallium metal, Ga2I3 and Ga2I4 based on the characteristic Raman spectra of these constituents.[5] This hypothesis was confirmed as two variants of gallium monoiodide were determined to have the chemical compositions [Ga0]2[Ga+][GaI4−], simplified as Ga2I4·2Ga, and [Ga0]2[Ga+]2[Ga2I62-], simplified as Ga2I3·Ga.[4][3]

When the incompletely reacted product was probed by NMR spectroscopy, it showed the presence gallium metal.[3] When probed by 127I NQR,[4] it showed the presence of Ga2I4 and further confirms the [Ga0]2[Ga+][GaI4−] assignment.[6] Raman spectroscopy has also confirmed this composition assignment.[4][7] All of the evidence from other spectroscopic methods, and power x-ray diffraction patterns, validates the assignment of [Ga0]2[Ga+][GaI4−] for the incompletely reacted gallium monoiodide variant.

When the completely reacted product was probed by 127I NQR, it showed the presence of Ga2I3.[4] Raman spectroscopy has also confirmed this assignment, as it aligned with those from a Ga4I6 reference.[4][7] Finally, power x-ray diffraction supports that this gallium monoiodide variant matches that of characteristic Ga2I3, which is different from that of GaI2.[4]

[Ga0]2[Ga+][GaI4−] converts to [Ga0]2[Ga+]2[Ga2I62-] over time.[4]

Reactions and derivatives

[edit]Gallium monoiodide is used as a precursor for a variety of reactions, acting as a lewis acid and a reducing agent. Early-on, gallium monoiodide was shown to produce alkylgallium diiodides via oxidative addition by reacting liquid gallium metal and iodine in the presence of an alkyl iodide.[1][2][8] Since then, other organogallium complexes have been synthesized, as well as Lewis base adducts and gallium based clusters.[8]

Gallium Lewis base adducts

[edit]

Gallium monoiodide reacts with various monodentate Lewis bases to form Ga(II), Ga(III), or mixed valent compounds, as well as gallium-based dimers and trimers. For example, gallium monoiodide can react with primary, secondary, and tertiary amines, secondary or tertiary phosphines or ethers to form Ga(II)-Ga(II) dimers.[2][8][10] Gallium monoiodide can also react with triphenylphosphine (PPh3) to form Ga(III)I3PPh3.[2] It also reacts with the less sterically hindered triethylphosphine (PEt3) to form a Ga(II)-Ga(I)-Ga(II) mixed valent complex with datively coordinated PEt3 ligands.[8][10] These reactions are believed to be a disproportionation, as gallium metal is produced in these reactions.[9]

Gallium monoiodide reacts with triphenylstibine to produce an SbPh3 fragment datively bonded to a GaPhI2 fragment.[11] The difference in reactivity between PPh3 and SbPh3, a heavy atom analogue of PPh3, can be attributed to a weaker Sb-C bond, allowing for transfer of a phenyl group from antimony to gallium. This suggests that gallium monoiodide can be used as a reducing agent as well.[8][11]

N-heterocyclic carbenes reacts with gallium monoiodide to form a complex with a sterically hindered isopropyl ligand.[9] However, gallium monoiodide reacts with diazabutadienes and subsequent reduction by potassium metal to form Ga analogs of N-heterocyclic carbenes.[8] Other Ga-based carbenes can be produced from gallium monoiodide precursor using Li(NacNac).[8]

Gallium monoiodide reacts with multidentate Lewis bases, such as bipyridine, phenyl-terpyridine, and bis(imino)pyridine ligands to form Ga(III) complexes.[8][12] Crystallographically, the bipyridine derivative has a distorted octahedral geometry, with a Ga–N bond length of 2.063 Å. The phenyl-terpyridine derivative adopts a distorted trigonal bipyramidal geometry where the two equatorial Ga–N bonds (as drawn) are longer than the axial Ga-N bond, with 2.104 Å and 2.007(5) Å, respectively. The average Ga-N bond length (2.071 Å) is similar to that of a neutral GaCl3(terpy) Lewis base adduct (2.086 Å).[13] The bis(imino)pyridine derivative has a distorted square-based pyramidal geometry. Like for the phenyl-terpyridine derivative, the equatorial imino Ga-N bonds (2.203 Å) are longer than the axial pyridyl Ga-N bond (2.014(7) A˚).[12] Despite these similar reactivities and bond characteristics, when gallium monoiodide was reacted with imino-substituted pyridines (RN=C(H)Py), unique reactivity was observed. Reductive coupling of the imino-substituted pyridines formed diamido-digallium(III) complexes.[12] These reactions display the ability of gallium monoiodides to form new C-C bonds.

Gallium heterocycles

[edit]Gallium monoiodide can also be used as a precursor to form gallium-based heterocycles. Reactions with diazabutadienes, {RN=C(H)}2, forms monomers or dimers based on the substituents on the diazabutadienes. More sterically hindered substituents such as tert-butyl have resulted in the formation of gallium(II) dimers, whereas reactions with alkyl or aryl substituted diazabutadienes have formed Ga(III) monomers.[8] Gallium monoiodide can be reacted with phenyl-substituted 1,4-diazabuta-1,3-dienes to form a gallium heterocycle with a diazabutadiene monoanion.[14] EPR spectroscopy has revealed that the diazabutadiene fragment is a paramagnetic monoanionic species rather than an ene-diamido dianion or a neutral ligand.[14] Thus, gallium monoiodide undergoes a disproportionation reaction to form a gallium(III) complex with deposition of a gallium metal.[8][14] Upon further reaction with a 1,4-dilithiated diazabutadiene, this gallium heterocycle forms a new complex with the diazabutadiene monoanion fragment datively bonded to the gallium center and an ene-diamido dianion covalently bonded to the Ga center.[14]

One very important reactivity of this gallium(III) heterocycle is its ability to access gallium analogues of N-heterocyclic carbenes upon reduction with potassium metal.[15] Although a gallium analogue of N-heterocyclic carbenes had been synthesized previously,[16] having access to heavier analogues of N-heterocylic carbenes from a synthetically more facile gallium monoiodide route has opened new avenues in coordination chemistry, such as access to new Ga-M bonds.[17][18][19]

Gallium monoiodide can also be used to access six-membered gallium(I) heterocycles that have parallels to gallium analogues of N-heterocyclic carbenes. These neutral gallium(I) heterocycles can be synthesized by reacting gallium monoiodide and Li[nacnac].[18][20]

Cyclopentadienyl complexes

[edit]Gallium monoiodide can easily be converted to half-sandwich complexes, (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and cyclopentadienylgallium.[21] (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) can be easily produced by reacting gallium monoiodide with a potassium salt of the desired ligand under toluene to avoid side products.[22][8]

Cyclopentadienylgallium, which is less sterically hindered than (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), can also be accessed using a gallium monoiodide. This ligand can be synthesized with a metathesis reaction of NaCp with gallium monoiodide.[23] This cyclopentadienylgallium ligand has been used to access a GaCp2I complex with datively bonded cyclopentadienylgallium. This complex showcases an uncommon donor-acceptor Ga-Ga bond. Cyclopentadienylgallium can also be used to access a Lewis acid B(C6F5)3 complex with a datively bonded cyclopentadienylgallium ligand.[23] For both of these two complexes, the (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) analogues have been synthesized and x-ray crystallography has supported that, as expected, (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) is a slightly stronger donor than cyclopentadienylgallium.

Like (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), cyclopentadienylgallium can also coordinate to transition metal complexes such as Cr(CO)5(cyclooctene) or Co2(CO)8 to yield CpGa–Cr(CO)5 or (thf)GaCp{Co(CO)4}2.[24] For CpGa–Cr(CO)5, the Ga-Cr bond length (239.6 pm) is similar to that for a (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) analogue (240.5 pm). For this complex, the trans effect is also observed, where the Cr-CO bond trans to the cyclopentadienylgallium ligand is contracted (186 pm) relative to the cis Cr-CO bonds (189.5 pm). While cyclopentadienylgallium can act as a terminal ligand similar to (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I), it was determined that cyclopentadienylgallium analogues react faster than their (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) counterparts. This can be attributed to the lower steric bulk of cyclopentadienylgallium.[24]

Unlike reactivity with Cr(CO)5(cyclooctene), reactivities of (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and cyclopentadienylgallium with Co2(CO)8 diverge significantly.[24] Dicobalt octacarbonyl, or Co2(CO)8, exists in various isomeric states. One such isomer contains two bridging CO ligands. When (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) reacts with Co2(CO)8, two equivalents of CO gas are released, forming (CO)3Co[μ2-(η5-GaCp*)]2-Co(CO)3. This is a derivative of the dicobalt octacarbonyl complex where the bridging CO moieties are replaced by bridging (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) moieties.[25] On the other hand, cyclopentadienylgallium enables oxidative addition to Co2(CO)8 to form (thf)GaCp{Co(CO)4}2, where gallium has sigma interactions to two Co(CO)4 units. The average Ga–Co bond length is 248.5 pm and gallium is in a formally +3 oxidation state in this new complex.[25] Overall, straightforward synthesis of cyclopentadienylgallium from a gallium monoiodide precursor has many merits in expanding the scope of transition metal chemistry with lower valent species.

Gallium clusters

[edit]

A variety of gallium clusters have also been synthesized from gallium monoiodide.[26] These clusters have often been isolated as salts with bulky silyl or germyl anions, such as [Si(SiMe3)3]−.[8] An example of an isolated gallium cluster is [Ga9{Si(SiMe3)3}6]−, which has a pentagonal bipyramidal polyhedral structure. It is synthesized by reacting gallium monoiodide with Li(thf)3Si(SiMe3)3 in toluene at -78 ˚C.[8][27] This reaction has been shown to access a wide array of products, which may be attributed to the wide range of gallium monoiodide compositions that have been subsequently probed. Of these products, [Ga9{Si(SiMe3)3}6]− is especially unique because Ga was found to have a very low average oxidation state (0.56) and also because this cluster has fewer R substituents than polyhedron vertices.[27] Other clusters that been isolated via similar reaction pathways include [Ga10{Si(SiMe3)3}6], which is a conjuncto-polyhedral cluster, and a closo-silatetragallane anion, which contains three 2-electron-2-center and three 2-electron-3-center bonds.[8][28][29] Interestingly, this latter species can only be synthesized when sub-stoichiometric quantities of I2 are utilized to access a "Ga2I3" intermediate species.[29] This is equivalent to reacting liquid gallium metal and iodine to pre-completion, which, as explained above, accesses the [Ga0]2[Ga+]2[Ga2I62-] variant of gallium monoiodide. This highlights the versatility of the gallium monoiodide precursor in accessing a wide range of gallium-based complexes.

Gallium monoiodide can also form cluster-type compounds with transition metals precursors. One example is the reaction between gallium monoiodide and (2,6-Pmp2C6H3)2Co, (Pmp = C6Me5), which yields a nido-type cluster.[30] This molecule is structurally similar to cubane, where the corners are metal and bridging iodine atoms, with one corner removed. This is a particularly unique Co-GaI cluster due to its unusual geometry for transition metal compounds containing heavy group 13 atoms such as gallium. The bond critical points and bond paths, as computed with QTAIM analysis, support that while there are Co-Ga bonds, there are no Ga-Ga bonds.[30]

Finally, gallium monoiodide has been able to form clusters with heavy gold atoms by acting as a reducing reagent when combined with (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) and triphenylphosphine-gold complexes(i.e. AuI(PPh3) or AuCl(PPh3)).[8][32] This cluster contained the first crystallographically confirmed Ga-Au bonds, consisting of a Au3 cluster ligated by Ga ligands. In addition, NBO analysis showed that the charge on the galliums within the (pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) ligands were much higher than the charge on the Au atoms and the charge on the gallium atoms within the GaI2 motifs. This suggests that non-bridging Ga-Au bonds are highly polarized, whereas the μ-bridging Ga-Au bonds are more non-polar covalent in character.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Dohmeier, Carsten; Loos, Dagmar; Schnöckel, Hansgeorg (1996). "Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Compounds: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 35 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1002/anie.199601291. ISSN 1521-3773.

- ^ a b c d Green, Malcolm L. H.; Mountford, Philip; Smout, Geoffrey J.; Speel, S. Robert (1990-01-01). "New synthetic pathways into the organometallic chemistry of gallium". Polyhedron. 9 (22): 2763–2765. doi:10.1016/S0277-5387(00)86809-6. ISSN 0277-5387.

- ^ a b c Widdifield, Cory M.; Jurca, Titel; Richeson, Darrin S.; Bryce, David L. (2012-03-16). "Using 69/71Ga solid-state NMR and 127I NQR as probes to elucidate the composition of "GaI"". Polyhedron. 35 (1): 96–100. doi:10.1016/j.poly.2012.01.003. ISSN 0277-5387.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Malbrecht, Brian J.; Dube, Jonathan W.; Willans, Mathew J.; Ragogna, Paul J. (2014-09-15). "Addressing the Chemical Sorcery of "GaI": Benefits of Solid-State Analysis Aiding in the Synthesis of P→Ga Coordination Compounds". Inorganic Chemistry. 53 (18): 9644–9656. doi:10.1021/ic501139w. ISSN 0020-1669. PMID 25184621.

- ^ Wilkinson, M.; Worrall, I. J. (1975-07-01). "Synthesis of alkylgallium diiodides". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 93 (1): 39–42. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)94142-1. ISSN 0022-328X.

- ^ Okuda, Tsutomu; Hamamoto, Hiroshi; Ishihara, Hideta; Negita, Hisao (1985-09-01). "79Br and 127I Nuclear Quadrupole Resonance of Mixed Valency Compounds Ga2X4(X=Br, I)". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 58 (9): 2731–2732. doi:10.1246/bcsj.58.2731. ISSN 0009-2673.

- ^ a b Beamish, J. C.; Wilkinson, M.; Worrall, I. J. (1978-07-01). "Facile synthesis of the lower valent halides of gallium, Ga2X4 (X = chloride, bromide, iodide) and tetragallium hexaiodide". Inorganic Chemistry. 17 (7): 2026–2027. doi:10.1021/ic50185a069. ISSN 0020-1669.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Baker, Robert J.; Jones, Cameron (2005-04-11). ""GaI": A versatile reagent for the synthetic chemist". Dalton Transactions (8): 1341–1348. doi:10.1039/B501310K. hdl:2262/69572. ISSN 1477-9234. PMID 15824768.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Robert J.; Bettentrup, Helga; Jones, Cameron (2003). "The Reactivity of Primary and Secondary Amines, Secondary Phosphanes and N-Heterocyclic Carbenes towards Group-13 Metal(I) Halides". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2003 (13): 2446–2451. doi:10.1002/ejic.200300068. ISSN 1099-0682.

- ^ a b Schnepf, Andreas; Doriat, Clemens (1997-01-01). "A simple synthesis for donor-stabilized Ga2I4 and Ga3I5 species and the X-ray crystal structure of Ga3I5·3PEt3". Chemical Communications (21): 2111–2112. doi:10.1039/A703776G. ISSN 1364-548X.

- ^ a b Cameron Jones; Christian Schulten; Andreas Stasch (2005-04-01). "[Gal2Ph(SbPh3)]: A Rare Tertiary Stibane-Gallium Complex Formed via a Reductive Sb-C Bond Cleavage Reaction". Main Group Metal Chemistry. 28 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1515/MGMC.2005.28.2.89. ISSN 0792-1241. S2CID 101459028.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Robert J.; Jones, Cameron; Kloth, Marc; Mills, David P. (2004-02-03). "The reactivity of gallium(I) and indium(I) halides towards bipyridines, terpyridines, imino-substituted pyridines and bis(imino)acenaphthenes". New Journal of Chemistry. 28 (2): 207–213. doi:10.1039/B310592J. ISSN 1369-9261.

- ^ Beran, G.; Carty, A. J.; Patel, H. A.; Palenik, Gus J. (1970-01-01). "A trans-effect in gallium complexes: the crystal structure of trichloro-(2,2′,2"-terpyridyl)gallium(III)". Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications (4): 222–223. doi:10.1039/C29700000222. ISSN 0577-6171.

- ^ a b c d e Pott, Thomas; Jutzi, Peter; Kaim, Wolfgang; Schoeller, Wolfgang W.; Neumann, Beate; Stammler, Anja; Stammler, Hans-Georg; Wanner, Matthias (July 2002). "Reactivity of "GaI" TowardN-Substituted 1,4-Diazabuta-1,3-dienes: Synthesis and Characterization of Gallium Heterocycles Containing Paramagnetic Diazabutadiene Monoanions". Organometallics. 21 (15): 3169–3172. doi:10.1021/om0200510. ISSN 0276-7333.

- ^ Baker, Robert J.; Farley, Robert D.; Jones, Cameron; Kloth, Marc; Murphy, Damien M. (2002-10-03). "The reactivity of diazabutadienes toward low oxidation state Group 13 iodides and the synthesis of a new gallium(I) carbene analogue". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (20): 3844–3850. doi:10.1039/B206605J. ISSN 1364-5447.

- ^ Schmidt, Eva S.; Jockisch, Alexander; Schmidbaur, Hubert (1999-10-01). "A Carbene Analogue with Low-Valent Gallium as a Heteroatom in a quasi-Aromatic Imidazolate Anion". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 121 (41): 9758–9759. doi:10.1021/ja9928780. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ Baker, Robert J.; Jones, Cameron; Mills, David P.; Murphy, Damien M.; Hey-Hawkins, Evamarie; Wolf, Robert (2006-12-14). "The reactivity of gallium-(I), -(II) and -(III) heterocycles towards Group 15 substrates: attempts to prepare gallium–terminal pnictinidene complexes". Dalton Transactions (1): 64–72. doi:10.1039/B511451A. ISSN 1477-9234. PMID 16357962.

- ^ a b c Baker, Robert J.; Jones, Cameron (2005-09-01). "The coordination chemistry and reactivity of group 13 metal(I) heterocycles". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 36th International Conference on Coordination Chemistry, Merida, Mexico, July 2004. 249 (17): 1857–1869. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.016. ISSN 0010-8545.

- ^ Jones, Cameron; Rose, Richard P.; Stasch, Andreas (2007-07-10). "Synthesis and characterisation of zinc gallyl complexes: First structural elucidations of Zn–Ga bonds". Dalton Transactions (28): 2997–2999. doi:10.1039/B706402K. ISSN 1477-9234. PMID 17622416.

- ^ a b Hardman, Ned J.; Eichler, Barrett E.; Power, Philip P. (2000-01-01). "Synthesis and characterization of the monomer Ga{(NDippCMe)2CH} (Dipp = C6H3Pri2-2,6): a low valent gallium(I) carbene analogue". Chemical Communications (20): 1991–1992. doi:10.1039/B005686N. ISSN 1364-548X.

- ^ Loos, Dagmar; Baum, Elke; Ecker, Achim; Schnöckel, Hansgeorg; Downs, Anthony J. (1997). "Hexameric Aggregates in Crystalline (Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl)gallium(I) at 200 K". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 36 (8): 860–862. doi:10.1002/anie.199708601. ISSN 1521-3773.

- ^ Jutzi, Peter; Schebaum, Lars Oliver (2002-07-15). "A novel synthetic route to pentaalkylcyclopentadienylgallium(I) compounds". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 654 (1): 176–179. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(02)01429-8. ISSN 0022-328X.

- ^ a b Schenk, Christian; Köppe, Ralf; Schnöckel, Hansgeorg; Schnepf, Andreas (2011). "A Convenient Synthesis of Cyclopentadienylgallium – The Awakening of a Sleeping Beauty in Organometallic Chemistry". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2011 (25): 3681–3685. doi:10.1002/ejic.201100672. ISSN 1099-0682.

- ^ a b c d Naglav, Dominik; Tobey, Briac; Schnepf, Andreas (2013). "Application of GaCp as a Ligand in Coordination Chemistry: Similarities and Differences to GaCp*". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2013 (24): 4146–4149. doi:10.1002/ejic.201300401. ISSN 1099-0682.

- ^ a b Jutzi, Peter; Neumann, Beate; Reumann, Guido; Stammler, Hans-Georg (1998-03-01). "Pentamethylcyclopentadienylgallium (Cp*Ga): Alternative Synthesis and Application as a Terminal and Bridging Ligand in the Chemistry of Chromium, Iron, Cobalt, and Nickel". Organometallics. 17 (7): 1305–1314. doi:10.1021/om970913a. ISSN 0276-7333.

- ^ Schnepf, Andreas; Schnöckel, Hansgeorg (2002). "Metalloid Aluminum and Gallium Clusters: Element Modifications on the Molecular Scale?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (19): 3532–3554. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3532::AID-ANIE3532>3.0.CO;2-4. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 12370894.

- ^ a b Köstler, Wolfgang; Linti, Gerald (1997). "Synthesis and Structure of a Tetragallane [R4Ga4I3]− and a Polyhedral Nonagallane [R6Ga9]". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 36 (23): 2644–2646. doi:10.1002/anie.199726441. ISSN 1521-3773.

- ^ Kehrwald, Michael; Köstler, Wolfgang; Rodig, Alexander; Linti, Gerald; Blank, Thomas; Wiberg, Nils (2001-03-01). "Ga10[Si(SiMe3)3]6, [Ga10(SitBu3)6]-, and [Ga13(SitBu3)6]-Syntheses and Structural Characterization of Novel Gallium Cluster Compounds". Organometallics. 20 (5): 860–867. doi:10.1021/om000703p. ISSN 0276-7333.

- ^ a b Linti, Gerald; Köstler, Wolfgang; Piotrowski, Holger; Rodig, Alexander (1998). "A Silatetragallane—Classical Heterobicyclopentane or closo-Polyhedron?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 37 (16): 2209–2211. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980904)37:16<2209::AID-ANIE2209>3.0.CO;2-3. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 29711437.

- ^ a b c d Blundell, Toby J.; Taylor, Laurence J.; Valentine, Andrew J.; Lewis, William; Blake, Alexander J.; McMaster, Jonathan; Kays, Deborah L. (2020-07-21). "A transition metal–gallium cluster formed via insertion of "GaI"". Chemical Communications. 56 (58): 8139–8142. doi:10.1039/D0CC03559A. ISSN 1364-548X. PMID 32691803.

- ^ Lu, Tian; Chen, Feiwu (2012). "Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 33 (5): 580–592. doi:10.1002/jcc.22885. ISSN 1096-987X. PMID 22162017. S2CID 13508697.

- ^ a b c Anandhi, U.; Sharp, Paul R. (2004). "A Gallium-Coated Gold Cluster". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (45): 6128–6131. doi:10.1002/anie.200461295. ISSN 1521-3773. PMID 15549757.