Linearized gravity: Difference between revisions

rm inconsistent reference to natural units; some language ce |

|||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 19 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Linear perturbations to solutions of nonlinear Einstein field equations}} |

|||

{{Expert needed|physics|date=February 2009}} |

|||

{{General relativity sidebar |equations}} |

{{General relativity sidebar |equations}} |

||

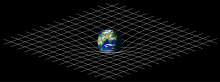

In the theory of [[general relativity]], '''linearized gravity''' is the application of [[perturbation theory]] to the [[Metric tensor (general relativity)|metric tensor]] that describes the geometry of [[spacetime]]. As a consequence, linearized gravity is an effective method for modeling the effects of gravity when the [[gravitational field]] is weak. The usage of linearized gravity is integral to the study of [[gravitational waves]] and weak-field [[gravitational lensing]]. |

|||

'''Linearized gravity''' is an approximation scheme in [[general relativity]] in which the [[nonlinear]] contributions from the [[spacetime]] [[Metric tensor (general relativity)|metric]] are ignored, simplifying the study of many problems while still producing useful approximate results. |

|||

== Weak-field approximation == |

|||

==The method== |

|||

The [[Einstein field equation]] (EFE) describing the geometry of [[spacetime]] is given as |

|||

In linearized gravity the [[metric tensor]], <math>g</math>, of spacetime is treated as a sum of an exact solution of [[Einstein's equations]] (often Minkowski spacetime) and a [[perturbation theory|perturbation]] <math>h</math>. |

|||

: <math>R_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2}Rg_{\mu\nu} = \kappa T_{\mu\nu}</math> |

|||

where <math>R_{\mu\nu}</math> is the [[Ricci tensor]], <math>R</math> is the [[Ricci scalar]], <math>T_{\mu\nu}</math> is the [[energy–momentum tensor]], <math>\kappa = 8 \pi G / c^4</math> is the [[Einstein gravitational constant]], and <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> is the [[spacetime]] [[metric tensor]] that represents the solutions of the equation. |

|||

Although succinct when written out using [[Einstein notation]], hidden within the Ricci tensor and Ricci scalar are exceptionally nonlinear dependencies on the metric tensor that render the prospect of finding [[Exact solutions in general relativity|exact solutions]] impractical in most systems. However, when describing systems for which the [[curvature]] of spacetime is small (meaning that terms in the EFE that are [[Quadratic function|quadratic]] in <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> do not significantly contribute to the equations of motion), one can model the solution of the field equations as being the [[Minkowski metric]]<ref group="note">This assumes that the background spacetime is flat. Perturbation theory applied in a spacetime that is already curved can work just as well when this term is replaced with the metric representing the curved background.</ref> <math>\eta_{\mu\nu}</math> plus a small perturbation term <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math>. In other words: |

|||

:<math>g \, =\eta+h</math> |

|||

: <math>g_{\mu\nu} = \eta_{\mu\nu} + h_{\mu\nu},\qquad |h_{\mu\nu}| \ll 1.</math> |

|||

In this regime, substituting the general metric <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> for this perturbative approximation results in a simplified expression for the Ricci tensor: |

|||

where <math>\eta</math> is the nondynamical background metric that is being perturbed about, and <math>h</math> represents the deviation of the true metric (<math>g</math>) from [[Minkowski spacetime|flat spacetime]]. |

|||

: <math>R_{\mu\nu} = \frac{1}{2}(\partial_\sigma\partial_\mu h^\sigma_\nu + \partial_\sigma\partial_\nu h^\sigma_\mu - \partial_\mu\partial_\nu h - \square h_{\mu\nu}),</math> |

|||

where <math>h = \eta^{\mu\nu}h_{\mu\nu}</math> is the [[Trace (linear algebra)|trace]] of the perturbation, <math>\partial_\mu</math> denotes the partial derivative with respect to the <math>x^\mu</math> coordinate of spacetime, and <math>\square = \eta^{\mu\nu} \partial_\mu \partial_\nu</math> is the [[d'Alembert operator]]. |

|||

Together with the Ricci scalar, |

|||

The perturbation is treated using the methods of [[perturbation theory]], "linearized" by ignoring all terms of order higher than one ([[Quadratic function|quadratic]] in <math>h</math>, [[Cubic function|cubic]] in <math>h</math> etc...) in the perturbation. |

|||

: <math>R = \eta_{\mu\nu}R^{\mu\nu} = \partial_\mu\partial_\nu h^{\mu\nu} - \square h,</math> |

|||

the left side of the field equation reduces to |

|||

: <math>R_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2}Rg_{\mu\nu} = \frac{1}{2}(\partial_\sigma\partial_\mu h^\sigma_\nu + \partial_\sigma\partial_\nu h^\sigma_\mu - \partial_\mu\partial_\nu h - \square h_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu}\partial_\rho\partial_\lambda h^{\rho\lambda} + \eta_{\mu\nu}\square h).</math> |

|||

and thus the EFE is reduced to a linear second order [[partial differential equation]] in terms of <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math>. |

|||

=== Gauge invariance === |

|||

==Applications== |

|||

The process of decomposing the general spacetime <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> into the Minkowski metric plus a perturbation term is not unique. This is due to that different choices for coordinates may give different forms for <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math>. In order to capture this phenomenon, the application of [[Gauge theory|gauge symmetry]] is introduced. |

|||

The [[Einstein field equation]]s (EFE), being nonlinear in the metric, are difficult to [[Exact solutions in general relativity|solve exactly]] and the above perturbation scheme allows linearized Einstein field equations to be obtained. These equations are linear in the metric, and the sum of two solutions of the linearized EFE is also a solution. The idea of 'ignoring the nonlinear part' is thus encapsulated in this linearization procedure. |

|||

Gauge symmetries are a mathematical device for describing a system that does not change when the underlying coordinate system is "shifted" by an infinitesimal amount. So although the perturbation metric <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math> is not consistently defined between different coordinate systems, the overall system which it describes ''is''. |

|||

The method is used to derive the Newtonian limit, including the first corrections, much like for a derivation of the existence of [[gravitational wave]]s that led, after [[Quantization (physics)|quantization]], to [[graviton]]s. This is why the conceptual approach of linearized gravity is the canonical one in [[particle physics]], [[string theory]], and more generally [[quantum field theory]] where classical (bosonic) fields are expressed as [[coherent state]]s of particles. |

|||

To capture this formally, the non-uniqueness of the perturbation <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math> is represented as being a consequence of the diverse collection of [[diffeomorphisms]] on spacetime that leave <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math> sufficiently small. Therefore, it is required that <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math> be defined in terms of a general set of diffeomorphisms, then select the subset of these that preserve the small scale that is required by the weak-field approximation. One may thus define <math>\phi</math> to denote an arbitrary diffeomorphism that maps the flat Minkowski spacetime to the more general spacetime represented by the metric <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math>. With this, the perturbation metric may be defined as the difference between the [[Pullback (differential geometry)|pullback]] of <math>g_{\mu\nu}</math> and the Minkowski metric: |

|||

This approximation is also known as the weak-field approximation as it is only valid if the perturbation ''h'' is very small. |

|||

: <math>h_{\mu\nu} = (\phi^*g)_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu}.</math> |

|||

The diffeomorphisms <math>\phi</math> may thus be chosen such that <math>|h_{\mu\nu}| \ll 1</math>. |

|||

Given then a vector field <math>\xi^\mu</math> defined on the flat background spacetime, an additional family of diffeomorphisms <math>\psi_\epsilon</math> may be defined as those generated by <math>\xi^\mu</math> and parameterized by <math>\epsilon > 0</math>. These new diffeomorphisms will be used to represent the coordinate transformations for "infinitesimal shifts" as discussed above. Together with <math>\phi</math>, a family of perturbations is given by |

|||

===Weak-field approximation=== |

|||

: <math>\begin{align} |

|||

In a weak-field approximation, the gauge symmetry is associated with [[diffeomorphism]]s with small "displacements" (diffeomorphisms with large displacements obviously violate the weak field approximation), which has the exact form (for infinitesimal transformations) |

|||

h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} &= [(\phi\circ\psi_\epsilon)^*g]_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu} \\ |

|||

&= [\psi^*_\epsilon(\phi^*g)]_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu} \\ |

|||

&= \psi^*_\epsilon(h + \eta)_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu} \\ |

|||

&= (\psi^*_\epsilon h)_{\mu\nu} + \epsilon\left[\frac{(\psi^*_\epsilon\eta)_{\mu\nu} - \eta_{\mu\nu}}{\epsilon}\right]. |

|||

\end{align}</math> |

|||

Therefore, in the limit <math>\epsilon\rightarrow 0</math>, |

|||

: <math>h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} = h_{\mu\nu} + \epsilon\mathcal{L}_\xi\eta_{\mu\nu}</math> |

|||

where <math>\mathcal{L}_\xi</math> is the [[Lie derivative]] along the vector field <math>\xi_\mu</math>. |

|||

The Lie derivative works out to yield the final ''gauge transformation'' of the perturbation metric <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math>: |

|||

:<math>\delta_{\vec{\xi}}h=\delta_{\vec{\xi}}g-\delta_{\vec{\xi}}\eta=\mathcal{L}_{\vec{\xi}}g=\mathcal{L}_{\vec{\xi}}\eta+\mathcal{L}_{\vec{\xi}}h= |

|||

: <math>h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} = h_{\mu\nu} + \epsilon(\partial_\mu\xi_\nu + \partial_\nu\xi_\mu),</math> |

|||

which precisely define the set of perturbation metrics that describe the same physical system. In other words, it characterizes the gauge symmetry of the linearized field equations. |

|||

=== Choice of gauge === |

|||

Where <math>\mathcal{L}</math> is the [[Lie derivative]] and we used the fact that η does not transform (by definition). Note that we are raising and lowering the indices with respect to η and not g and taking the [[covariant derivative]]s ([[Levi-Civita connection]]) with respect to η. This is the standard practice in linearized gravity. The way of thinking in linearized gravity is this: the background metric η is the metric and h is a field propagating over the spacetime with this metric. |

|||

By exploiting gauge invariance, certain properties of the perturbation metric can be guaranteed by choosing a suitable vector field <math>\xi^\mu</math>. |

|||

==== Transverse gauge ==== |

|||

In the weak field limit, this gauge transformation simplifies to |

|||

To study how the perturbation <math>h_{\mu\nu}</math> distorts measurements of length, it is useful to define the following spatial tensor: |

|||

: <math>s_{ij} = h_{ij} - \frac{1}{3}\delta^{kl}h_{kl}\delta_{ij}</math> |

|||

(Note that the indices span only spatial components: <math>i,j\in\{1,2,3\}</math>). Thus, by using <math>s_{ij}</math>, the spatial components of the perturbation can be decomposed as |

|||

: <math>h_{ij} = s_{ij} - \Psi\delta_{ij}</math> |

|||

where <math>\Psi = \frac{1}{3}\delta^{kl}h_{kl}</math>. |

|||

The tensor <math>s_{ij}</math> is, by construction, [[trace (linear algebra)|trace]]less and is referred to as the ''strain'' since it represents the amount by which the perturbation [[Gravitational wave#Effects of passing|stretches and contracts measurements of space]]. In the context of studying [[gravitational waves|gravitational radiation]], the strain is particularly useful when utilized with the ''transverse gauge.'' This gauge is defined by choosing the spatial components of <math>\xi^\mu</math> to satisfy the relation |

|||

:<math>\delta_{\vec{\xi}}h_{\mu\nu}\approx \left(\mathcal{L}_{\vec{\xi}}\eta\right)_{\mu\nu}=\xi_{\nu;\mu} + \xi_{\mu;\nu}</math> |

|||

: <math>\nabla^2\xi^j + \frac{1}{3}\partial_j\partial_i\xi^i = -\partial_i s^{ij},</math> |

|||

then choosing the time component <math>\xi^0</math> to satisfy |

|||

: <math>\nabla^2\xi^0 = \partial_i h_{0i} + \partial_0\partial_i\xi^i.</math> |

|||

After performing the gauge transformation using the formula in the previous section, the strain becomes spatially transverse: |

|||

The weak-field approximation is useful in finding the values of certain constants, for example in the [[Einstein field equations]] and in the [[Schwarzschild metric]]. |

|||

: <math>\partial_i s^{ij}_{(\epsilon)} = 0,</math> |

|||

with the additional property: |

|||

: <math>\partial_i h^{0i}_{(\epsilon)} = 0.</math> |

|||

==== Synchronous gauge ==== |

|||

== Linearized Einstein field equations== |

|||

The ''synchronous gauge'' simplifies the perturbation metric by requiring that the metric not distort measurements of time. More precisely, the synchronous gauge is chosen such that the non-spatial components of <math>h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu}</math> are zero, namely |

|||

The '''linearized Einstein field equations''' (linearized EFE) are an approximation to [[Einstein's field equations]] that is valid for a weak [[gravitational field]] and is used to simplify many problems in [[general relativity]] and to discuss the phenomena of [[gravitational radiation]]. The approximation can also be used to derive [[Newtonian gravity]] as the weak-field approximation of [[general relativity|Einsteinian gravity]]. |

|||

: <math>h^{(\epsilon)}_{0\nu} = 0.</math> |

|||

This can be achieved by requiring the time component of <math>\xi^\mu</math> to satisfy |

|||

: <math>\partial_0\xi^0 = -h_{00}</math> |

|||

and requiring the spatial components to satisfy |

|||

: <math>\partial_0\xi^i = \partial_i\xi^0 - h_{0i}.</math> |

|||

==== Harmonic gauge ==== |

|||

The equations are obtained by assuming the [[metric tensor (general relativity)|spacetime metric]] is only slightly different from some baseline metric (usually a [[Minkowski metric]]). Then the difference in the metrics can be considered as a field on the baseline metric, whose behaviour is approximated by a set of linear equations. |

|||

The ''[[Harmonic coordinate condition|harmonic gauge]]'' (also referred to as the ''Lorenz gauge''<ref group="note">Not to be confused with Lorentz.</ref>) is selected whenever it is necessary to reduce the linearized field equations as much as possible. This can be done if the condition |

|||

: <math>\partial_\mu h^\mu_\nu = \frac{1}{2}\partial_\nu h</math> |

|||

is true. To achieve this, <math>\xi_\mu</math> is required to satisfy the relation |

|||

: <math>\square\xi_\mu = -\partial_\nu h^\nu_\mu + \frac{1}{2}\partial_\mu h.</math> |

|||

Consequently, by using the harmonic gauge, the [[Einstein tensor]] <math>G_{\mu\nu} = R_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2}Rg_{\mu\nu}</math> reduces to |

|||

=== Derivation for the Minkowski metric === |

|||

: <math>G_{\mu\nu} = -\frac{1}{2}\square\left(h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2}h^{(\epsilon)}\eta_{\mu\nu}\right).</math> |

|||

Starting with the metric for a [[spacetime]] in the form |

|||

Therefore, by writing it in terms of a "trace-reversed" metric, <math>\bar{h}^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} = h^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} - \frac{1}{2}h^{(\epsilon)}\eta_{\mu\nu}</math>, the linearized field equations reduce to |

|||

: <math>\square \bar{h}^{(\epsilon)}_{\mu\nu} = -2\kappa T_{\mu\nu}.</math> |

|||

This can be solved exactly, to produce the [[wave equation|wave solutions]] that define [[gravitational wave|gravitational radiation]]. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

:<math>g_{ab} = \eta_{ab} + h_{ab}</math> |

|||

{{cols}} |

|||

* [[Correspondence principle]] |

|||

* [[Gravitoelectromagnetism]] |

|||

* [[Lanczos tensor]] |

|||

* [[Parameterized post-Newtonian formalism]] |

|||

* [[Post-Newtonian expansion]] |

|||

* [[Quasinormal mode]] |

|||

{{colend}} |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

where <math>\, \eta_{ab}</math> is the Minkowski metric and <math>\, h_{ab}</math> — sometimes written as <math>\epsilon \, \gamma_{ab}</math> — is the deviation of <math>\, g_{ab}</math> from it. <math>h</math> must be negligible compared to <math>\eta</math>: <math>\left| h_{\mu \nu} \right| \ll 1</math> (and similarly for all derivatives of <math>h</math>). Then one ignores all products of <math>h</math> (or its derivatives) with <math>h</math> or its derivatives (equivalent to ignoring all terms of higher order than 1 in <math>\epsilon</math>). It is further assumed in this approximation scheme that all indices of h and its derivatives are raised and lowered with <math>\eta</math>. |

|||

{{reflist|group="note"|2}} |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

The metric h is clearly symmetric, since g and η are. The consistency condition <math>g_{ab}g^{bc}=\delta_a{}^c</math> shows that |

|||

* {{cite book | author = Sean M. Carroll | title = Spacetime and Geometry, an Introduction to General Relativity | year = 2003 | publisher = Pearson | isbn = 978-0805387322}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

:<math>g^{ab} \, = \eta^{ab} - h^{ab}</math> |

|||

* {{wikiquote-inline}} |

|||

The [[Christoffel symbols]] can be calculated as |

|||

:<math>2 \Gamma ^a_{bc} = (h^a{}_{b,c}+h^a{}_{c,b}-h_{bc,}{}^a)</math> |

|||

where <math>h_{bc,}{}^a \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\ \eta^{ar} h_{bc,r}</math>, and this is used to calculate the [[Riemann tensor]]: |

|||

:<math>2R^a{}_{bcd} = 2(\Gamma^a_{bd,c}-\Gamma^a_{bc,d}) |

|||

= \eta^{ae} (h_{eb,dc}+h_{ed,bc}-h_{bd,ec} - h_{eb,cd}-h_{ec,bd}+h_{bc,ed}) =</math> |

|||

:<math> = \eta^{ae} (h_{ed,bc}-h_{bd,ec}-h_{ec,bd}+h_{bc,ed}) |

|||

= h^a_{d,bc} - h_{bd,}{}^ a{}_c + h_{bc,}{}^a{}_d - h^a{}_{c,bd}</math> |

|||

Using <math>R_{bd}= \delta ^c{}_a R^a{}_{bcd}</math> gives |

|||

:<math>2R_{bd}= h^r_{d,br} + h^r_{b,dr} -h_{,bd} - h_{bd, rs} \eta ^{rs}</math> |

|||

For the Ricci scalar we have<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.tapir.caltech.edu/~chirata/ph236/lec08.pdf|title=Lecture VIII: Linearized gravity |author=Christopher M. Hirata |date=November 5, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

: |

|||

:<math>R = R_{bd} \eta^{bd}= h^{a b}_{, a b} - \square h </math> |

|||

Then the linearized Einstein equations are |

|||

:<math> 8\pi T_{bd} \, = R_{bd} - R_{ac} \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd} / 2 </math> |

|||

or |

|||

:<math> 8\pi T_{bd} = (h^r_{d,br} + h^r_{b,dr} -h_{,bd} - h_{bd, r}{}^r - h^r_{s,r}{}^s \eta_{bd})/2 + ( h_{,a}{}^a \eta_{bd} + h_{ac, r}{}^r \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}) /4 </math> |

|||

Or, equivalently: |

|||

:<math> 8\pi (T_{bd} - T_{ac} \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}/2) \, = R_{bd} </math> |

|||

:<math> 16\pi (T_{bd} - T_{ac} \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}/2) \, = h^r_{d,br} + h^r_{b,dr} -h_{,bd} - h_{bd, rs} \eta ^{rs}</math> |

|||

== With a coordinate condition == |

|||

If one uses the Lorentz invariant [[harmonic coordinate condition]] |

|||

:<math> h_{\alpha \beta,\gamma} \eta^{\beta \gamma} = \frac12 h_{\beta \gamma,\alpha} \eta^{\beta \gamma} \,,</math> |

|||

then the last form above of the linearized Einstein equation simplifies to |

|||

:<math> 16\pi (T_{bd} - T_{ac} \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}/2) \, = \, - h_{bd, rs} \eta ^{rs} \,.</math> |

|||

To solve it, this can be rewritten as |

|||

:<math> \Delta h_{bd} = {-16\pi G \over c^4} (T_{bd} - T_{ac} \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}/2) + \frac{ \partial^2 h_{bd} }{ c^2 {\partial t}^2 } \,</math> |

|||

where ∆ is the [[Laplacian]] on a spatial slice. If the stress-energy changes slowly (velocities are low compared to ''c''), then this gives |

|||

:<math> h_{bd} (r) = \frac{-1}{4\pi} \int \left( {-16\pi G \over c^4} (T_{bd} (s) - T_{ac} (s) \eta^{ac} \eta_{bd}/2) + \frac{ \partial^2 h_{bd} (s) }{ c^2 {\partial t}^2 } \right) \frac{1}{\vert r-s \vert} d^3 s \,</math> |

|||

as a generalization of the Newtonian formula for [[gravitational potential]]. This is solved iteratively by first replacing the second time derivative by zero and then inserting the ''h'' so obtained repeatedly until convergence. |

|||

== Applications == |

|||

The linearized EFE are used primarily in the theory of [[gravitational radiation]], where the gravitational field far from the source is approximated by these equations. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

*[[Correspondence principle]] |

|||

*[[Gravitoelectromagnetism]] |

|||

*[[Lanczos tensor]] |

|||

*[[Parameterized post-Newtonian formalism]] |

|||

*[[Post-Newtonian expansion]] |

|||

*[[Quasinormal mode]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

* {{cite book | author=Stephani, Hans | title=General Relativity: An Introduction to the Theory of the Gravitational Field, | location=Cambridge | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1990 | isbn=0-521-37941-5}} |

|||

* {{cite book |author1=Adler, Ronald |author2=Bazin, Maurice' |author3=Schiffer, Menahem |lastauthoramp=yes| title=Introduction to General Relativity | location=New York | publisher=McGraw-Hill | year=1965 | isbn=0-07-000423-4}} |

|||

{{Theories of gravitation}} |

|||

{{Relativity}} |

{{Relativity}} |

||

Latest revision as of 12:52, 26 August 2024

| General relativity |

|---|

|

In the theory of general relativity, linearized gravity is the application of perturbation theory to the metric tensor that describes the geometry of spacetime. As a consequence, linearized gravity is an effective method for modeling the effects of gravity when the gravitational field is weak. The usage of linearized gravity is integral to the study of gravitational waves and weak-field gravitational lensing.

Weak-field approximation

[edit]The Einstein field equation (EFE) describing the geometry of spacetime is given as

where is the Ricci tensor, is the Ricci scalar, is the energy–momentum tensor, is the Einstein gravitational constant, and is the spacetime metric tensor that represents the solutions of the equation.

Although succinct when written out using Einstein notation, hidden within the Ricci tensor and Ricci scalar are exceptionally nonlinear dependencies on the metric tensor that render the prospect of finding exact solutions impractical in most systems. However, when describing systems for which the curvature of spacetime is small (meaning that terms in the EFE that are quadratic in do not significantly contribute to the equations of motion), one can model the solution of the field equations as being the Minkowski metric[note 1] plus a small perturbation term . In other words:

In this regime, substituting the general metric for this perturbative approximation results in a simplified expression for the Ricci tensor:

where is the trace of the perturbation, denotes the partial derivative with respect to the coordinate of spacetime, and is the d'Alembert operator.

Together with the Ricci scalar,

the left side of the field equation reduces to

and thus the EFE is reduced to a linear second order partial differential equation in terms of .

Gauge invariance

[edit]The process of decomposing the general spacetime into the Minkowski metric plus a perturbation term is not unique. This is due to that different choices for coordinates may give different forms for . In order to capture this phenomenon, the application of gauge symmetry is introduced.

Gauge symmetries are a mathematical device for describing a system that does not change when the underlying coordinate system is "shifted" by an infinitesimal amount. So although the perturbation metric is not consistently defined between different coordinate systems, the overall system which it describes is.

To capture this formally, the non-uniqueness of the perturbation is represented as being a consequence of the diverse collection of diffeomorphisms on spacetime that leave sufficiently small. Therefore, it is required that be defined in terms of a general set of diffeomorphisms, then select the subset of these that preserve the small scale that is required by the weak-field approximation. One may thus define to denote an arbitrary diffeomorphism that maps the flat Minkowski spacetime to the more general spacetime represented by the metric . With this, the perturbation metric may be defined as the difference between the pullback of and the Minkowski metric:

The diffeomorphisms may thus be chosen such that .

Given then a vector field defined on the flat background spacetime, an additional family of diffeomorphisms may be defined as those generated by and parameterized by . These new diffeomorphisms will be used to represent the coordinate transformations for "infinitesimal shifts" as discussed above. Together with , a family of perturbations is given by

Therefore, in the limit ,

where is the Lie derivative along the vector field .

The Lie derivative works out to yield the final gauge transformation of the perturbation metric :

which precisely define the set of perturbation metrics that describe the same physical system. In other words, it characterizes the gauge symmetry of the linearized field equations.

Choice of gauge

[edit]By exploiting gauge invariance, certain properties of the perturbation metric can be guaranteed by choosing a suitable vector field .

Transverse gauge

[edit]To study how the perturbation distorts measurements of length, it is useful to define the following spatial tensor:

(Note that the indices span only spatial components: ). Thus, by using , the spatial components of the perturbation can be decomposed as

where .

The tensor is, by construction, traceless and is referred to as the strain since it represents the amount by which the perturbation stretches and contracts measurements of space. In the context of studying gravitational radiation, the strain is particularly useful when utilized with the transverse gauge. This gauge is defined by choosing the spatial components of to satisfy the relation

then choosing the time component to satisfy

After performing the gauge transformation using the formula in the previous section, the strain becomes spatially transverse:

with the additional property:

Synchronous gauge

[edit]The synchronous gauge simplifies the perturbation metric by requiring that the metric not distort measurements of time. More precisely, the synchronous gauge is chosen such that the non-spatial components of are zero, namely

This can be achieved by requiring the time component of to satisfy

and requiring the spatial components to satisfy

Harmonic gauge

[edit]The harmonic gauge (also referred to as the Lorenz gauge[note 2]) is selected whenever it is necessary to reduce the linearized field equations as much as possible. This can be done if the condition

is true. To achieve this, is required to satisfy the relation

Consequently, by using the harmonic gauge, the Einstein tensor reduces to

Therefore, by writing it in terms of a "trace-reversed" metric, , the linearized field equations reduce to

This can be solved exactly, to produce the wave solutions that define gravitational radiation.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Sean M. Carroll (2003). Spacetime and Geometry, an Introduction to General Relativity. Pearson. ISBN 978-0805387322.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Linearized gravity at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Linearized gravity at Wikiquote

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}h_{\mu \nu }^{(\epsilon )}&=[(\phi \circ \psi _{\epsilon })^{*}g]_{\mu \nu }-\eta _{\mu \nu }\\&=[\psi _{\epsilon }^{*}(\phi ^{*}g)]_{\mu \nu }-\eta _{\mu \nu }\\&=\psi _{\epsilon }^{*}(h+\eta )_{\mu \nu }-\eta _{\mu \nu }\\&=(\psi _{\epsilon }^{*}h)_{\mu \nu }+\epsilon \left[{\frac {(\psi _{\epsilon }^{*}\eta )_{\mu \nu }-\eta _{\mu \nu }}{\epsilon }}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a05873bdab89d32bee0adeb30afde6baad0a2bbb)