The Knight of the Burning Pestle: Difference between revisions

KolbertBot (talk | contribs) m Bot: HTTP→HTTPS (v485) |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: date, website, title. Changed bare reference to CS1/2. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Grimes2 | #UCB_webform 709/1085 |

||

| (39 intermediate revisions by 27 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|1607 play by Francis Beaumont}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=September 2013}} |

{{EngvarB|date=September 2013}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2018}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2018}} |

||

[[ |

[[File:Knight of the Burning Pestle.jpg|thumb|right|Title page from a 1635 edition of ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle''.]] |

||

{{Italic title}} |

{{Italic title}} |

||

'''''The Knight of the Burning Pestle''''' is a play in five acts by [[Francis Beaumont]], first performed at [[Blackfriars Theatre]] in 1607<ref name="Whitted">{{cite journal|last1=Whitted|first1=Brent E.|title=Staging Exchange: Why "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" Flopped at Blackfriars in 1607|journal=Early Theatre|date=2012|volume=15|issue=2|pages=111–130|jstor=43499628}}</ref><ref name="Smith">{{cite journal|last1=Smith|first1=Joshua S.|title=Reading Between the Acts: Satire and the Interludes in The Knight of the Burning Pestle|journal=Studies in Philology|date=Summer 2012|volume=109|issue=4|pages=474–495|url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/481431/pdf| |

'''''The Knight of the Burning Pestle''''' is a play in five acts by [[Francis Beaumont]], first performed at [[Blackfriars Theatre]] in 1607<ref name="Whitted">{{cite journal|last1=Whitted|first1=Brent E.|title=Staging Exchange: Why "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" Flopped at Blackfriars in 1607|journal=Early Theatre|date=2012|volume=15|issue=2|pages=111–130|jstor=43499628}}</ref><ref name="Smith">{{cite journal|last1=Smith|first1=Joshua S.|title=Reading Between the Acts: Satire and the Interludes in The Knight of the Burning Pestle|journal=Studies in Philology|date=Summer 2012|volume=109|issue=4|pages=474–495|doi=10.1353/sip.2012.0027 |s2cid=162251374 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/481431/pdf|access-date=12 November 2017}}</ref><ref name="Billington">{{cite news|last1=Billington|first1=Michael|title=The Knight of the Burning Pestle review|url=https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/feb/27/the-knight-burning-pestle-adele-thomas-review|access-date=12 November 2017|work=The Guardian|date=27 February 2014}}</ref> and published in a [[book size|quarto]] in 1613.<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Patterson|editor1-first=Michael|title=The Oxford Dictionary of Plays|url=https://archive.org/details/oxforddictionary0000patt|url-access=registration|date=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|isbn=978-0-19-860417-4|page=[https://archive.org/details/oxforddictionary0000patt/page/224 224]}}</ref> It is the earliest whole [[parody]] (or [[pastiche]]) play in English. The play is a satire on [[romance (poetry)|chivalric romances]] in general, similar to ''[[Don Quixote]]'', and a parody of [[Thomas Heywood]]'s ''[[The Four Prentices of London]]'' and [[Thomas Dekker (poet)|Thomas Dekker]]'s ''[[The Shoemaker's Holiday]]''. It breaks the [[fourth wall]] from its outset. |

||

==Text== |

==Text== |

||

[[File:Francis-Beaumont.jpg|thumb|right|[[Francis Beaumont]], circa 1600]] |

[[File:Francis-Beaumont.jpg|thumb|right|[[Francis Beaumont]], circa 1600]] |

||

It is most likely that the play was written for the child actors at [[Blackfriars Theatre]], where [[John Marston (poet)|John Marston]] had previously had plays produced. In addition to the textual history testifying to a Blackfriars origin, there are multiple references within the text to Marston, to the actors as children (notably from the Citizen's Wife, who seems to recognise the actors from their school), and other indications that the performance took place in a house known for biting satire and sexual |

It is most likely that the play was written for the child actors at [[Blackfriars Theatre]], where [[John Marston (poet)|John Marston]] had previously had plays produced. In addition to the textual history testifying to a Blackfriars origin, there are multiple references within the text to Marston, to the actors as children (notably from the Citizen's Wife, who seems to recognise the actors from their school), and other indications that the performance took place in a house known for biting satire and sexual innuendo. Blackfriars specialised in satire, according to Andrew Gurr (quoted in Hattaway, ix), and Michael Hattaway suggests that the dissonance of the youth of the players and the gravity of their roles combined with the multiple internal references to holiday revels because the play had a [[Shrovetide]] or midsummer's day first production (Hattaway xxi and xiii). The play is certainly carnivalesque, but the date of the first performance is purely speculative. The second quarto publication came in 1635, with a third the same year. The play was omitted from the [[Beaumont and Fletcher folios|first Beaumont and Fletcher folio]] of 1647 but included in the second folio of 1679. The play was later widely thought to be the joint work of Beaumont and [[John Fletcher (playwright)|John Fletcher]].<ref>It was so credited in the London revivals of 1904, 1920, 1932, 1975 and 1981 detailed in the "Staging" section</ref> |

||

==Characters== |

==Characters== |

||

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

{{div col|colwidth=30em}} |

||

*Speaker of the Prologue |

* Speaker of the Prologue |

||

*A Citizen (George) |

* A Citizen (George) |

||

*His Wife (Nell) |

* His Wife (Nell) |

||

*Rafe, his Apprentice |

* Rafe, his Apprentice |

||

* |

* Boys |

||

*Venturewell, a Merchant |

* Venturewell, a Merchant |

||

* |

* Humphrey |

||

*Old Merrythought |

* Old Merrythought |

||

*Michael Merrythought, his son |

* Michael Merrythought, his son |

||

*Jasper Merrythought, another son |

* Jasper Merrythought, another son |

||

*Host of an Inn |

* Host of an Inn |

||

* |

* Tapster |

||

*Barber |

* Barber |

||

*Three Men, supposed captives |

* Three Men, supposed captives |

||

*Sergeant |

* Sergeant |

||

*William Hammerton |

* William Hammerton |

||

*George Greengoose |

* George Greengoose |

||

*Soldiers, and Attendants |

* Soldiers, and Attendants |

||

*Luce, Daughter of Venturewell |

* Luce, Daughter of Venturewell |

||

*Mistress Merrythought |

* Mistress Merrythought |

||

*Woman, supposed a captive |

* Woman, supposed a captive |

||

*Pompiona, Daughter of the King of Moldavia |

* Pompiona, Daughter of the King of Moldavia |

||

* Susan, Cobbler's maid in Milk Street |

|||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

Scene: London and the neighbouring Country, except Act IV Scene ii |

Scene: London and the neighbouring Country, except for Act IV Scene ii which is set in Moldavia. |

||

As a play called |

As a play called ''The London Merchant'' is about to be performed, a Citizen and his Wife 'in the audience' interrupt to complain that the play will misrepresent the middle-class citizens of the city. The Citizen, who identifies himself as a grocer, climbs onto the stage, bringing his Wife up to sit with him. They demand that the players put on a play of their own choosing and suggest that the Citizen's own apprentice, Rafe,<ref>In mid-20th century revivals the name was usually rendered as "Ralph": see "A Jacobean Romp", ''The Times'', 25 November 1920, p. 10 and "The Old Vic: 'The Knight Of The Burning Pestle'.", ''The Times'', 5 January 1932, p. 10</ref> should be given a part. Rafe demonstrates his dramatic skills by quoting Shakespeare, and a part is created for him as a [[knight errant]]. He refers to himself as a 'Grocer Errant' and has a burning [[pestle]] on his shield as a [[heraldic device]]. |

||

This meta- |

This meta-plot is intercut with the main plot of the interrupted play, ''The London Merchant,'' in which Jasper Merrythought, the merchant's apprentice, is in love with his master's daughter, Luce, and must elope with her to save her from marriage to Humphrey, a City man of fashion. Luce pretends to Humphrey that she has made an unusual vow: she will only marry a man who has the spirit to run away with her. She knows that Humphrey will immediately inform her father. She intends to fake an elopement with Humphrey, knowing that her father will allow this to happen, but then to drop him and meet up with Jasper. |

||

Meanwhile, Jasper's mother has decided to leave her husband Old Merrythought, who |

Meanwhile, Jasper's mother has decided to leave her husband, Old Merrythought, who has spent all his savings in drinking and partying. When Jasper seeks his mother's help, she rejects him in favour of his younger brother Michael. She tells Michael that she has jewellery that she can sell to live on while he learns a trade. They leave Merrythought, and lose themselves in a wood where she misplaces her jewellery. Jasper arrives to meet Luce and finds the jewels. Luce and Humphrey appear. Jasper, as planned, knocks over Humphrey and escapes with Luce. The Grocer Errant arrives, believing when he sees the distraught Mrs Merrythought that he has met a damsel in distress. He takes the Merrythoughts to an inn, expecting the host to accommodate them chivalrously without charge. When the host demands payment, the Grocer Errant is perplexed. The host tells him there are people in distress he must save from an evil barber named Barbaroso (a barber surgeon who is attempting cures on people with venereal diseases). He effects a daring rescue of Barbaroso's patients. |

||

The Citizen and his Wife demand more chivalric and exotic adventures for Rafe, |

The Citizen and his Wife demand more chivalric and exotic adventures for Rafe, and a scene is created in which the Grocer Errant must go to Moldavia where he meets a princess who falls in love with him. But he says that he has already plighted his troth to Susan, a cobbler's maid in Milk Street. The princess reluctantly lets him go, lamenting that she cannot come to England, as she has always dreamed of tasting English beer. |

||

Jasper tests Luce's love by pretending he intends to kill her because of the way her father has treated him. She is shocked, but declares her devotion to him. Humphrey and her father arrive with other men. They attack Jasper and drag Luce away. The merchant locks Luce in her room. Jasper feigns death and writes a letter to the merchant with a pretend dying apology for his behaviour. The coffin, with Jasper hiding within, is carried to the merchant's house, where Luce laments his demise. Jasper rises and explains his plan to save her from marriage to Humphrey: Luce is to take Jasper's place in the coffin while Jasper remains hidden in the house. When the merchant enters, Jasper pretends to be his [[Banquo|own ghost]] and scares the merchant into expelling Humphrey. A chastened Mrs Merrythought returns to her husband. Jasper reveals he is still alive. The merchant asks for Old Merrythought's forgiveness and consents to Jasper's match with Luce. |

|||

returns to her husband and by this point Luce has been delivered to the house in the coffin. Jasper appears and reveals he is still alive. Then the merchant also appears and asks for Old Merrythought's forgiveness. The merchant gives consent to Jasper's match with Luce. The Citizen and the Wife demand that Rafe's part of the drama should also have an appropriate ending, so Rafe is given a heroic chivalric dying scene, and everyone is satisfied. |

|||

The Citizen and his Wife demand that Rafe's part in the drama should also have an appropriate ending, and he is given a heroic death scene. Everyone is satisfied. |

|||

==Satire== |

==Satire== |

||

{{Unreferenced section|date=February 2023}} |

|||

The play hits a number of satirical and parodic points. The audience is satirised, with the interrupting grocer, but the domineering and demanding merchant class is also satirised in the main plot. Beaumont makes fun of the new demand for stories of the middle classes for the middle classes, even as he makes fun of that class's actual taste for an exoticism and a chivalry that is entirely hyperbolic. The Citizen and his Wife are bombastic, sure of themselves, and certain that their prosperity carries with it mercantile advantages (the ability to demand a different play for their admission fee than the one the actors have prepared). |

The play hits a number of satirical and parodic points. The audience is satirised, with the interrupting grocer, but the domineering and demanding merchant class is also satirised in the main plot. Beaumont makes fun of the new demand for stories of the middle classes for the middle classes, even as he makes fun of that class's actual taste for an exoticism and a chivalry that is entirely hyperbolic. The Citizen and his Wife are bombastic, sure of themselves, and certain that their prosperity carries with it mercantile advantages (the ability to demand a different play for their admission fee than the one the actors have prepared). |

||

| Line 55: | Line 60: | ||

==Staging== |

==Staging== |

||

{{Unreferenced section|date=February 2023}} |

|||

If written for Blackfriars, ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle'' would have initially been produced in a small private theatre, with minimal stage properties. However, the private theatres were first to introduce the practice of having audience members seated on the stage proper (according to Gurr, ''op cit.'' in Hattaway ix), which is a framing device for this play's action. Additionally, the higher cost of a private theatre (sixpence, compared to a penny at some public theatres) changed the composition of the audience and would have suggested a more critically aware (and demanding) crowd. The play makes use of several "interludes," which would have been spare entertainments between the acts (but which are integrated into the performance in this case), again emphasising the smallness and spareness of the initial staging (as interludes would have allowed for technicians to arrange the lights and scenery and to put actors in place). |

If written for Blackfriars, ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle'' would have initially been produced in a small private theatre, with minimal stage properties. However, the private theatres were first to introduce the practice of having audience members seated on the stage proper (according to Gurr, ''op cit.'' in Hattaway ix), which is a framing device for this play's action. Additionally, the higher cost of a private theatre (sixpence, compared to a penny at some public theatres) changed the composition of the audience and would have suggested a more critically aware (and demanding) crowd. The play makes use of several "interludes," which would have been spare entertainments between the acts (but which are integrated into the performance in this case), again emphasising the smallness and spareness of the initial staging (as interludes would have allowed for technicians to arrange the lights and scenery and to put actors in place). |

||

Revivals of the play are largely undocumented, but some are attested. Hattaway suggests that it was performed in the [[Cockpit Theatre]] in [[Drury Lane]] in 1635, at court the next year, and then after the Restoration at the [[Theatre Royal Drury Lane]] in 1662 and again in 1665 and 1667 (Hattaway xxix). The play "has proved popular with amateur and university groups," according to Hattaway, but not with professional troupes. |

Revivals of the play are largely undocumented, but some are attested. Hattaway suggests that it was performed in the [[Cockpit Theatre]] in [[Drury Lane]] in 1635, at court the next year, and then after the Restoration at the [[Theatre Royal Drury Lane]] in 1662 and again in 1665 and 1667 (Hattaway xxix). The play "has proved popular with amateur and university groups," according to Hattaway, but not with professional troupes. |

||

==Reception== |

==Reception== |

||

The play was a failure when it was first performed, |

The play was a failure when it was first performed, although it won approval over the next generation or two. In [[Richard Brome]]'s ''[[The Sparagus Garden]]'' (1635), the character Rebecca desires to see it "above all plays." Beaumont's comedy was performed at Court by [[Queen Henrietta's Men]] on 28 February 1636 ([[Old Style and New Style dates|new style]]).<ref>See Zitner's edition, pp. 42–3.</ref> |

||

==Revivals== |

==Revivals== |

||

| Line 65: | Line 72: | ||

===London revivals=== |

===London revivals=== |

||

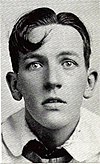

[[File:Coward pestle.jpg|thumb|100px|left|[[Noël Coward]] as Rafe in 1920]] |

[[File:Coward pestle.jpg|thumb|100px|left|[[Noël Coward]] as Rafe in 1920]] |

||

The play was revived in London in 1904, with [[Nigel Playfair]] in the principal role of Rafe.<ref>"Drama", ''The Athenaeum'', 19 November 1904, p.703</ref> In 1920 the young [[Noël Coward]] starred as Rafe in a [[Birmingham Repertory Theatre]] production which transferred to the West End. ''[[The Times]]'' called the play "the jolliest thing in London".<ref>"A Jacobean Romp", ''The Times'', 25 November 1920, p. 10</ref> In 1932 the play was staged at the [[Old Vic]], with [[Ralph Richardson]] as Rafe and [[Sybil |

The play was revived in London in 1904, with [[Nigel Playfair]] in the principal role of Rafe.<ref>"Drama", ''The Athenaeum'', 19 November 1904, p.703</ref> In 1920 the young [[Noël Coward]] starred as Rafe in a [[Birmingham Repertory Theatre]] production which transferred to the West End. ''[[The Times]]'' called the play "the jolliest thing in London".<ref>"A Jacobean Romp", ''The Times'', 25 November 1920, p. 10</ref> In 1932 the play was staged at the [[Old Vic]], with [[Ralph Richardson]] as Rafe and [[Sybil Thorndike]] as the Citizen's Wife.<ref>"The Old Vic: 'The Knight Of The Burning Pestle'.", ''The Times'', 5 January 1932, p. 10</ref> The [[Greenwich Theatre]] presented the play in 1975, with [[Gordon Reid (actor)|Gordon Reid]] as Rafe.<ref>Wardle, Irving, "'The Knight of the Burning Pestle', Greenwich," ''The Times'', 13 June 1975, p. 9</ref> The [[Royal Shakespeare Company]] performed it in 1981, with [[Timothy Spall]] in the lead.<ref>Wardle, Irving, "'The Knight of the Burning Pestle', Aldwych," ''The Times'', 18 April 1981, p. 10</ref> In a 2005 revival at the [[Barbican Centre|Barbican Theatre]] Rafe was played by Spall's son [[Rafe Spall|Rafe]], who was named after the character in the play.<ref>Spencer, Charles, "The unfunniest show in town", ''[[The Daily Telegraph]]'', 4 October 2005, p. 26</ref> The play was performed as part of the opening season of the [[Sam Wanamaker Theatre]] in 2014.<ref name=Telegraph>{{cite web|author1=Dominic Cavendish|title=The Knight of the Burning Pestle, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, review|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/theatre-reviews/10666407/The-Knight-of-the-Burning-Pestle-Sam-Wanamaker-Playhouse-review.html|website=telegraph.co.uk|publisher=The Telegraph|access-date=3 January 2015|date=2014-02-27}}</ref> |

||

===American productions=== |

===American productions=== |

||

In 1957 the [[Old Globe Theatre]] in [[San Diego]] presented ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle''.<ref name=IMDb>{{cite web|title=The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1938 TV Movie)|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0416895/fullcredits?ref_=tt_cl_sm#cast|website=www.imdb.com| |

In 1957 the [[Old Globe Theatre]] in [[San Diego]] presented ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle''.<ref name=IMDb>{{cite web|title=The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1938 TV Movie)|url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0416895/fullcredits?ref_=tt_cl_sm#cast|website=www.imdb.com|access-date=3 January 2015}}</ref> The [[American Shakespeare Center]] (then the Shenandoah Shakespeare Express) staged it in 1999 and revived it in 2003 at the Blackfriars Playhouse in [[Staunton, Virginia]], a recreation of Shakespeare's [[Blackfriars Theatre]]. In 1974 the [[Long Wharf Theatre]] in [[New Haven]], CT, presented a shortened adaptation by [[Brooks Jones]] that turned it into a [[musical comedy]] with new songs by [[Peter Schickele]]. <ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPmf56N-mP0&list=FLaArEuxr4_3wZO9DSadsyxA | title=Peter Schickele: Songs from the Knight of the Burning Pestle | website=[[YouTube]] | date=28 August 2022 }}</ref> The American Shakespeare Center's "Rough, Rude, and Boisterous tour" of 2009 to 2010 also included the play.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.americanshakespearecenter.com/v.php?pg=376 |title=Knight of the Burning Pestle |work=American Shakespeare Center |access-date=25 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090502223208/http://www.americanshakespearecenter.com/v.php?pg=376 |archive-date=2 May 2009 |url-status=dead}}</ref> The Theater at Monmouth staged the play in the summer of 2013.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pressherald.com/life/theater-at-monmouth-finds-surprising-depth-in-our-town_2013-07-04.html|title=Theater at Monmouth finds surprising depth in 'Our Town'|date=4 July 2013}}</ref> In June 2016, [[Theatre Pro Rata]], a small professional theater in [[St. Paul, Minnesota]], staged a 90-minute version of the play with eight actors, four in the play–within–the–play playing multiple roles.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.twincities.com/2016/06/08/more-than-400-years-later-knight-of-the-burning-pestle-still-charms/|title=More than 400 years later, 'Knight of the Burning Pestle' still charms|date=9 June 2016}}</ref> With a cast of 12, The Independent Shakespeare Company of Los Angeles staged a full performance in [[Griffith Park]] in July 2022. <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.broadwayworld.com/los-angeles/article/Review-GROCERS-GONE-WILD-IN-KNIGHT-OF-THE-BURNING-PESTLE-at-Independent-Shakespeare-Company-In-Griffith-Park-20220715|title=Review: GROCERS GONE WILD IN KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE at Independent Shakespeare Company In Griffith Park|date=17 July 2022}}</ref> In 2023, the play is being presented at the [[Lucille Lortel Theatre]] by Red Bull Theater in association with Fiasco Theater in the first major New York revival in over 50 years.<ref>{{Cite web |title=THE KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE {{!}} Off-Broadway |url=https://www.redbulltheater.com/knight-of-the-burning-pestle |access-date=2023-02-22 |website=Red Bull Theater |language=en}}</ref> |

||

===1938 TV film=== |

===1938 TV film=== |

||

A 90-minute television film version<ref name=IMDb /> was broadcast by [[BBC Television]] on |

A 90-minute television film version<ref name=IMDb /> was broadcast by [[BBC Television]] on 19<ref name=RT1>{{cite web|title=Radio Times Archive|url=http://www.radiotimesarchive.co.uk/pdf/RT-TV-1938.pdf |publisher=BBC|access-date=3 January 2015|pages=18|date=1938-12-16}}</ref> and 30<ref name=RT2>{{cite web|title=Radio Times Archive|url=http://www.radiotimesarchive.co.uk/pdf/RT-TV-1938.pdf |publisher=BBC|access-date=3 January 2015|pages=38|date=1938-12-23}}</ref> December 1938. The film had music by [[Frederic Austin]] and starred [[Frederick Ranalow]] as Merrythought, [[Hugh E. Wright]] as The Citizen, [[Margaret Yarde]] as Wife, [[Manning Whiley]] as Tim and [[Alex McCrindle]] as George Greengoose. |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[1613 in literature]] |

* [[1613 in literature]] |

||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*Beaumont, Francis. ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle.'' Michael Hattaway, ed. New Mermaids. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002. |

* Beaumont, Francis. ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle.'' Michael Hattaway, ed. New Mermaids. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002. |

||

* ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle.'' Sheldon P. Zitner, ed. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004. |

* ''The Knight of the Burning Pestle.'' Sheldon P. Zitner, ed. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004. |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=September 2013}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Wikisource}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{Librivox book |title=The Knight of the Burning Pestle |author=Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher}} |

|||

{{Beaumont and Fletcher canon}} |

{{Beaumont and Fletcher canon}} |

||

| Line 94: | Line 103: | ||

[[Category:1607 plays]] |

[[Category:1607 plays]] |

||

[[Category:English Renaissance plays]] |

[[Category:English Renaissance plays]] |

||

[[Category:Parodies]] |

[[Category:Parodies of literature]] |

||

[[Category:Plays by Francis Beaumont]] |

[[Category:Plays by Francis Beaumont]] |

||

[[Category:Satirical plays]] |

[[Category:Satirical plays]] |

||

Latest revision as of 15:44, 7 September 2024

The Knight of the Burning Pestle is a play in five acts by Francis Beaumont, first performed at Blackfriars Theatre in 1607[1][2][3] and published in a quarto in 1613.[4] It is the earliest whole parody (or pastiche) play in English. The play is a satire on chivalric romances in general, similar to Don Quixote, and a parody of Thomas Heywood's The Four Prentices of London and Thomas Dekker's The Shoemaker's Holiday. It breaks the fourth wall from its outset.

Text

[edit]

It is most likely that the play was written for the child actors at Blackfriars Theatre, where John Marston had previously had plays produced. In addition to the textual history testifying to a Blackfriars origin, there are multiple references within the text to Marston, to the actors as children (notably from the Citizen's Wife, who seems to recognise the actors from their school), and other indications that the performance took place in a house known for biting satire and sexual innuendo. Blackfriars specialised in satire, according to Andrew Gurr (quoted in Hattaway, ix), and Michael Hattaway suggests that the dissonance of the youth of the players and the gravity of their roles combined with the multiple internal references to holiday revels because the play had a Shrovetide or midsummer's day first production (Hattaway xxi and xiii). The play is certainly carnivalesque, but the date of the first performance is purely speculative. The second quarto publication came in 1635, with a third the same year. The play was omitted from the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647 but included in the second folio of 1679. The play was later widely thought to be the joint work of Beaumont and John Fletcher.[5]

Characters

[edit]- Speaker of the Prologue

- A Citizen (George)

- His Wife (Nell)

- Rafe, his Apprentice

- Boys

- Venturewell, a Merchant

- Humphrey

- Old Merrythought

- Michael Merrythought, his son

- Jasper Merrythought, another son

- Host of an Inn

- Tapster

- Barber

- Three Men, supposed captives

- Sergeant

- William Hammerton

- George Greengoose

- Soldiers, and Attendants

- Luce, Daughter of Venturewell

- Mistress Merrythought

- Woman, supposed a captive

- Pompiona, Daughter of the King of Moldavia

- Susan, Cobbler's maid in Milk Street

Plot

[edit]Scene: London and the neighbouring Country, except for Act IV Scene ii which is set in Moldavia.

As a play called The London Merchant is about to be performed, a Citizen and his Wife 'in the audience' interrupt to complain that the play will misrepresent the middle-class citizens of the city. The Citizen, who identifies himself as a grocer, climbs onto the stage, bringing his Wife up to sit with him. They demand that the players put on a play of their own choosing and suggest that the Citizen's own apprentice, Rafe,[6] should be given a part. Rafe demonstrates his dramatic skills by quoting Shakespeare, and a part is created for him as a knight errant. He refers to himself as a 'Grocer Errant' and has a burning pestle on his shield as a heraldic device.

This meta-plot is intercut with the main plot of the interrupted play, The London Merchant, in which Jasper Merrythought, the merchant's apprentice, is in love with his master's daughter, Luce, and must elope with her to save her from marriage to Humphrey, a City man of fashion. Luce pretends to Humphrey that she has made an unusual vow: she will only marry a man who has the spirit to run away with her. She knows that Humphrey will immediately inform her father. She intends to fake an elopement with Humphrey, knowing that her father will allow this to happen, but then to drop him and meet up with Jasper.

Meanwhile, Jasper's mother has decided to leave her husband, Old Merrythought, who has spent all his savings in drinking and partying. When Jasper seeks his mother's help, she rejects him in favour of his younger brother Michael. She tells Michael that she has jewellery that she can sell to live on while he learns a trade. They leave Merrythought, and lose themselves in a wood where she misplaces her jewellery. Jasper arrives to meet Luce and finds the jewels. Luce and Humphrey appear. Jasper, as planned, knocks over Humphrey and escapes with Luce. The Grocer Errant arrives, believing when he sees the distraught Mrs Merrythought that he has met a damsel in distress. He takes the Merrythoughts to an inn, expecting the host to accommodate them chivalrously without charge. When the host demands payment, the Grocer Errant is perplexed. The host tells him there are people in distress he must save from an evil barber named Barbaroso (a barber surgeon who is attempting cures on people with venereal diseases). He effects a daring rescue of Barbaroso's patients.

The Citizen and his Wife demand more chivalric and exotic adventures for Rafe, and a scene is created in which the Grocer Errant must go to Moldavia where he meets a princess who falls in love with him. But he says that he has already plighted his troth to Susan, a cobbler's maid in Milk Street. The princess reluctantly lets him go, lamenting that she cannot come to England, as she has always dreamed of tasting English beer.

Jasper tests Luce's love by pretending he intends to kill her because of the way her father has treated him. She is shocked, but declares her devotion to him. Humphrey and her father arrive with other men. They attack Jasper and drag Luce away. The merchant locks Luce in her room. Jasper feigns death and writes a letter to the merchant with a pretend dying apology for his behaviour. The coffin, with Jasper hiding within, is carried to the merchant's house, where Luce laments his demise. Jasper rises and explains his plan to save her from marriage to Humphrey: Luce is to take Jasper's place in the coffin while Jasper remains hidden in the house. When the merchant enters, Jasper pretends to be his own ghost and scares the merchant into expelling Humphrey. A chastened Mrs Merrythought returns to her husband. Jasper reveals he is still alive. The merchant asks for Old Merrythought's forgiveness and consents to Jasper's match with Luce.

The Citizen and his Wife demand that Rafe's part in the drama should also have an appropriate ending, and he is given a heroic death scene. Everyone is satisfied.

Satire

[edit]The play hits a number of satirical and parodic points. The audience is satirised, with the interrupting grocer, but the domineering and demanding merchant class is also satirised in the main plot. Beaumont makes fun of the new demand for stories of the middle classes for the middle classes, even as he makes fun of that class's actual taste for an exoticism and a chivalry that is entirely hyperbolic. The Citizen and his Wife are bombastic, sure of themselves, and certain that their prosperity carries with it mercantile advantages (the ability to demand a different play for their admission fee than the one the actors have prepared).

The broader humour of the play derives from innuendo and sexual jokes, as well as joking references to other dramatists. The players, for example, plant a winking joke at the Citizen's expense, as the pestle of Rafe's herald is a phallic metaphor, and a burning pestle/penis implies syphilis, on the one hand, and sexual bravado, on the other. The inability of the Citizen and Wife to comprehend how they are satirised, or to understand the main plot, allows the audience to laugh at itself, even as it admits its complicity with the Citizen's boorish tastes.

Staging

[edit]If written for Blackfriars, The Knight of the Burning Pestle would have initially been produced in a small private theatre, with minimal stage properties. However, the private theatres were first to introduce the practice of having audience members seated on the stage proper (according to Gurr, op cit. in Hattaway ix), which is a framing device for this play's action. Additionally, the higher cost of a private theatre (sixpence, compared to a penny at some public theatres) changed the composition of the audience and would have suggested a more critically aware (and demanding) crowd. The play makes use of several "interludes," which would have been spare entertainments between the acts (but which are integrated into the performance in this case), again emphasising the smallness and spareness of the initial staging (as interludes would have allowed for technicians to arrange the lights and scenery and to put actors in place).

Revivals of the play are largely undocumented, but some are attested. Hattaway suggests that it was performed in the Cockpit Theatre in Drury Lane in 1635, at court the next year, and then after the Restoration at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in 1662 and again in 1665 and 1667 (Hattaway xxix). The play "has proved popular with amateur and university groups," according to Hattaway, but not with professional troupes.

Reception

[edit]The play was a failure when it was first performed, although it won approval over the next generation or two. In Richard Brome's The Sparagus Garden (1635), the character Rebecca desires to see it "above all plays." Beaumont's comedy was performed at Court by Queen Henrietta's Men on 28 February 1636 (new style).[7]

Revivals

[edit]London revivals

[edit]

The play was revived in London in 1904, with Nigel Playfair in the principal role of Rafe.[8] In 1920 the young Noël Coward starred as Rafe in a Birmingham Repertory Theatre production which transferred to the West End. The Times called the play "the jolliest thing in London".[9] In 1932 the play was staged at the Old Vic, with Ralph Richardson as Rafe and Sybil Thorndike as the Citizen's Wife.[10] The Greenwich Theatre presented the play in 1975, with Gordon Reid as Rafe.[11] The Royal Shakespeare Company performed it in 1981, with Timothy Spall in the lead.[12] In a 2005 revival at the Barbican Theatre Rafe was played by Spall's son Rafe, who was named after the character in the play.[13] The play was performed as part of the opening season of the Sam Wanamaker Theatre in 2014.[14]

American productions

[edit]In 1957 the Old Globe Theatre in San Diego presented The Knight of the Burning Pestle.[15] The American Shakespeare Center (then the Shenandoah Shakespeare Express) staged it in 1999 and revived it in 2003 at the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia, a recreation of Shakespeare's Blackfriars Theatre. In 1974 the Long Wharf Theatre in New Haven, CT, presented a shortened adaptation by Brooks Jones that turned it into a musical comedy with new songs by Peter Schickele. [16] The American Shakespeare Center's "Rough, Rude, and Boisterous tour" of 2009 to 2010 also included the play.[17] The Theater at Monmouth staged the play in the summer of 2013.[18] In June 2016, Theatre Pro Rata, a small professional theater in St. Paul, Minnesota, staged a 90-minute version of the play with eight actors, four in the play–within–the–play playing multiple roles.[19] With a cast of 12, The Independent Shakespeare Company of Los Angeles staged a full performance in Griffith Park in July 2022. [20] In 2023, the play is being presented at the Lucille Lortel Theatre by Red Bull Theater in association with Fiasco Theater in the first major New York revival in over 50 years.[21]

1938 TV film

[edit]A 90-minute television film version[15] was broadcast by BBC Television on 19[22] and 30[23] December 1938. The film had music by Frederic Austin and starred Frederick Ranalow as Merrythought, Hugh E. Wright as The Citizen, Margaret Yarde as Wife, Manning Whiley as Tim and Alex McCrindle as George Greengoose.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Whitted, Brent E. (2012). "Staging Exchange: Why "The Knight of the Burning Pestle" Flopped at Blackfriars in 1607". Early Theatre. 15 (2): 111–130. JSTOR 43499628.

- ^ Smith, Joshua S. (Summer 2012). "Reading Between the Acts: Satire and the Interludes in The Knight of the Burning Pestle". Studies in Philology. 109 (4): 474–495. doi:10.1353/sip.2012.0027. S2CID 162251374. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Billington, Michael (27 February 2014). "The Knight of the Burning Pestle review". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Patterson, Michael, ed. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of Plays. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-19-860417-4.

- ^ It was so credited in the London revivals of 1904, 1920, 1932, 1975 and 1981 detailed in the "Staging" section

- ^ In mid-20th century revivals the name was usually rendered as "Ralph": see "A Jacobean Romp", The Times, 25 November 1920, p. 10 and "The Old Vic: 'The Knight Of The Burning Pestle'.", The Times, 5 January 1932, p. 10

- ^ See Zitner's edition, pp. 42–3.

- ^ "Drama", The Athenaeum, 19 November 1904, p.703

- ^ "A Jacobean Romp", The Times, 25 November 1920, p. 10

- ^ "The Old Vic: 'The Knight Of The Burning Pestle'.", The Times, 5 January 1932, p. 10

- ^ Wardle, Irving, "'The Knight of the Burning Pestle', Greenwich," The Times, 13 June 1975, p. 9

- ^ Wardle, Irving, "'The Knight of the Burning Pestle', Aldwych," The Times, 18 April 1981, p. 10

- ^ Spencer, Charles, "The unfunniest show in town", The Daily Telegraph, 4 October 2005, p. 26

- ^ Dominic Cavendish (27 February 2014). "The Knight of the Burning Pestle, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, review". telegraph.co.uk. The Telegraph. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b "The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1938 TV Movie)". www.imdb.com. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Peter Schickele: Songs from the Knight of the Burning Pestle". YouTube. 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Knight of the Burning Pestle". American Shakespeare Center. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Theater at Monmouth finds surprising depth in 'Our Town'". 4 July 2013.

- ^ "More than 400 years later, 'Knight of the Burning Pestle' still charms". 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Review: GROCERS GONE WILD IN KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE at Independent Shakespeare Company In Griffith Park". 17 July 2022.

- ^ "THE KNIGHT OF THE BURNING PESTLE | Off-Broadway". Red Bull Theater. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Radio Times Archive" (PDF). BBC. 16 December 1938. p. 18. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ "Radio Times Archive" (PDF). BBC. 23 December 1938. p. 38. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

References

[edit]- Beaumont, Francis. The Knight of the Burning Pestle. Michael Hattaway, ed. New Mermaids. New York: W. W. Norton, 2002.

- The Knight of the Burning Pestle. Sheldon P. Zitner, ed. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004.

External links

[edit]- The Knight of the Burning Pestle at Faded Page (Canada)

- Text of play (PDF)

The Knight of the Burning Pestle public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Knight of the Burning Pestle public domain audiobook at LibriVox