Cranial drill: Difference between revisions

trim spammy refs, trim WP:NOTNEWS content about academic research |

No edit summary |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Tool for drilling simple burr holes (trepanation) or for creating larger openings in the skull}} |

|||

{{Infobox occupation |

{{Infobox occupation |

||

|name= Cranial drill |

|name = Cranial drill |

||

|image= Pneumatic surgical drill.jpg |

|image = Pneumatic surgical drill.jpg |

||

|caption= High-speed pneumatic surgical drill with cranial drill bit |

|caption = High-speed pneumatic surgical drill with cranial drill bit |

||

|activity_sector= [[Surgery]], [[ |

|activity_sector = [[Surgery]], [[craniotomy]], [[craniectomy]] |

||

|competencies= |

|competencies = |

||

|established= |

|established = |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Utah specific University should be indicated ]] |

|||

| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

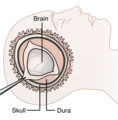

A '''cranial drill''', also known as a '''craniotome''', is a tool for drilling simple [[Trepanning|burr holes]] (trepanation) or for creating larger openings in the [[human skull|skull]]. This exposes the [[brain]] and allows operations like [[craniotomy]] and [[craniectomy]] to be done. The [[drill]] itself can be ''manually'' or ''electrically'' driven, and primarily |

A '''cranial drill''', also known as a '''craniotome''', is a tool for drilling simple [[Trepanning|burr holes]] (trepanation) or for creating larger openings in the [[human skull|skull]]. This exposes the [[Human brain|brain]] and allows operations like [[craniotomy]] and [[craniectomy]] to be done. The [[drill]] itself can be ''manually'' or ''electrically'' driven, and primarily consists of a handpiece and a [[drill bit]] which is a sharp tool that has a form similar to [[Archimedes' screw]], this instrument must be inserted into the drill chuck to perform holes and remove materials. The trepanation tool is generally equipped with a [[clutch]] which automatically disengages once it touches a softer tissue, thus preventing tears in the [[dura mater]]. For larger openings, the craniotome is an instrument that has replaced manually pulled [[Wire saw|saw wires]] in craniotomies from the 1980s. |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

=== Cranial drill === |

=== Cranial drill === |

||

{{see also|History of surgery}} |

{{see also|History of surgery|History of neurology and neurosurgery}} |

||

The oldest evidence of a hole being applied on a |

The oldest evidence of a hole being applied on a human's brain with a drill dates from c. 4000 B.C.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Cohut |first1=Maria |title=Skull-drilling: The ancient roots of modern neurosurgery |url=https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/322109.php |website=Medical News Today |date=12 June 2018 |access-date=28 September 2018}}</ref> |

||

The oldest cranial drilling instrument was found in France, and subsequent use evidenced by the Ancient Romans, Egyptians, and in [[Trepanation in Mesoamerica]]. The practice of [[trepanning]] is also evidenced |

The oldest cranial drilling instrument was found in France, and subsequent use was evidenced by the Ancient Romans, Egyptians, and in [[Trepanation in Mesoamerica]]. The practice of [[trepanning]] is also evidenced in Ancient [[Greece]], [[North America|North]] and [[South America]], [[Africa]], [[Polynesia]] and the [[Far East]]. The conceivable reasons why ancient humans developed the technique of drilling the head could be religious, ritual or medical factors.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Wylie |first1=Robin |title=Why our ancestors drilled holes in each other's skulls |url=http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160826-why-our-ancestors-drilled-holes-in-each-others-skulls |website=BBC |access-date=10 November 2018}}</ref> The first trepanning procedure consisted of different types of tools and techniques: at the beginning the only material that was available for use, it was a sharp and carved rock. The development of The [[Hippocratic Corpus]], written in the fifth century B.C., is the first written source that can be found about trepanning. The aim of the procedure described in "On Wounds in the Head" was to allow the stagnant blood to escape from the head through a hole. The drill that was used at the time is similar to modern ones but was operated by hand rotation.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Gross |first1=Charles G. |title=Trepanation from the Paleolothic to the internet |url=http://www.princeton.edu/~cggross/trepanation.pdf |access-date=10 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924134625/http://www.princeton.edu/~cggross/trepanation.pdf |archive-date=24 September 2015 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

In the 15th century, people began to believe that drilling was a cure for mental problems due to a magical ''[[stone of madness]]'' or ''stone of folly'' in the head, which had to be removed. Paintings that portray this practice exist, the most |

In the 15th century, people began to believe that drilling was a cure for mental problems due to a magical ''[[stone of madness]]'' or ''stone of folly'' in the head, which had to be removed. Paintings that portray this practice exist, the most significant ones include ''The Extraction of the Stone of Madness'' c. 1488–1516 by [[Hieronymus Bosch]] and ''A Surgeon Extracting the Stone of Folly'' by [[Pieter Huys]].<ref name="FerreiraDrillingHoles" /> |

||

[[File:Hieronymus Bosch 053 detail.jpg|thumb|left|''The |

[[File:Hieronymus Bosch 053 detail.jpg|thumb|left|''The Extraction of the Stone of Madness'', Hieronymus Bosch]] |

||

From the Renaissance ages, cranial drilling continued to evolve and surgical practice was used less due to the high mortality rate. It was used only for some interventions, such as the treatment of hemorrhages, depressed fractures and penetrating the head. Also the name for the surgery changed from trepanning to |

From the Renaissance ages, cranial drilling continued to evolve and surgical practice was used less due to the high mortality rate. It was used only for some interventions, such as the treatment of hemorrhages, depressed fractures and penetrating the head. Also, the name for the surgery changed from trepanning to craniotomy. |

||

In the late 1860s, [[E.G. Squier]] |

In the late 1860s, the archaeologist [[E.G. Squier]] discovered a skull in an ancient Inca cemetery. This specific skull was anticipated to be of the [[pre-Columbian era]]. The [[skull]] exhibited a large rectangle-shaped hole on the top. The skull was brought it back to the [[United States]], and his findings were presented to the [[New York Academy of Medicine]]. Squier argued that the brain was injected with a tool called a ''burin'' which was used on woods and metals before. Traces showed human hand prints. He concluded that the skull and brain evidenced recovery from prehistoric brain surgery, potentially prolonging the patient's life.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Fawcett |first1=Kristin |title=Trepanation: The History of One of the World's Oldest Surgeries |url=http://mentalfloss.com/article/70309/trepanation-history-one-worlds-oldest-surgeries |website=MentalFloss |date=January 2016 |access-date=26 November 2018}}</ref> |

||

[[ |

[[Metallurgy]] was a technique that allowed the use of saws and [[scalpels]]. Other cultures came about experimenting through the usage of glass.<ref name="FerreiraDrillingHoles">{{cite web |last1=Ferreira |first1=Becky |title=Madness Stones to New Age Medicine: A History of Drilling Holes in Our Heads |url=https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/wnjaaz/madness-stones-to-new-age-medicine-a-history-of-drilling-holes-in-our-heads |website=Motherboard |access-date=10 November 2018}}</ref> |

||

Dr [[Bart Hughes]] has declared that evolution caused a decrease in partial brain functions, mainly in the human consciousness. Whereas others increased, like speech and reasoning. The changes in performance are due to the enhancement of the extensiveness of blood. Which is located in the capillaries of the human brain.<ref name="MITPeopleWithHoles">{{cite web |last1=Michell |first1=John |title=The People With Holes In Their Heads |url=http://www.mit.edu/people/scottm/good/trepanning.html |website=MIT |accessdate=22 November 2018}}</ref> |

|||

These performances in the human brain are related to a higher level of vision. That a child still copes with because their membranes around the brain let them get in touch with dreams, imagination and intense perception. <ref name="MITPeopleWithHoles" /> |

|||

To reach ones goal, to increase his level of vision one must decideto remove a part of there skull by cutting a small disc of its bone. Hughes, conducted his first operation in 1962 on himself using an electric drill,[[surgical knife]] and a [[hypodermic needle]]. <ref>{{cite web |title=An illustrated history of trepanation|url=https://scienceblogs.com/neurophilosophy/2008/01/24/an-illustrated-history-of-trep |website=Science Blog |accessdate=22 November 2018}}</ref> Amongst other surgeries on fellow collogues he operated. The medical and legal authorities declared that his discovery was awful and Hughes was sent to Dutch lunatic asylum. <ref name="MITPeopleWithHoles" /> |

|||

[[File:1750 Trepanationsbesteck anagoria.JPG|thumb|right|Craniontonomy set, 18th century; Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg]] |

|||

=== Craniotome === |

|||

The first invention of a craniotome was designed and created by John H. Bent, a mechanical engineer and owner of Standard Pneumatic Motor Company, under contract with Hall Air Instruments of [[Santa Barbara, California]].<ref name="Bent John Patent">{{cite web |last1=Bent |first1=John H. |title=Patent US4199160A |url=https://patents.google.com/patent/US4199160A/en |website=Google Patents |accessdate=25 November 2018}}</ref> When Hall was subsequently acquired by [[3M Company]] (which was then actively developing and marketing surgical instruments), the 3M [[Craniotome]] became widely used in neurosurgery, replacing the [[Gigli saw]] (manually pulled saw wires) as the primary means of opening the skull for access to the brain for surgical procedures. |

|||

Bent designed the original Craniotome around a small, lightweight, very high speed (approximately 70,000 rpm) pneumatic turbine motor he had invented for use in industrial wire-wrapping tools and other air-powered hand-held devices. <ref name="Bent John Patent" /> While with [[3M|3M Company]], Bent went on to design and create a number of additional air-powered surgical instruments, including the 3M Mini-Driver and 3M Maxi-Driver, for orthopedic procedures on small bones and large bones, respectively, using adaptations of his original high-speed [[Pneumatic motor|pneumatic turbine motor]]. |

|||

One of the first craniotomes ever used in surgery was applied on John Bent himself, who required life-saving neurosurgery for a brain abscess that was discovered around the time the tool was being put into production. |

|||

== Application == |

== Application == |

||

A cranial drill is currently used for [[ |

A cranial drill is currently used for [[neurosurgery]] operations. The procedure of trepanning is applied to patients who suffer for example a [[traumatic brain injury]] or a [[stroke]]. In these cases, it might be necessary to drill a hole in the skull to be able to access the [[dura mater]] or the brain itself, and to relieve brain pressure or blood clots.<ref>{{cite web |title=Trepanation |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/trepanation |website=Encyclopedia.com |access-date=10 November 2018}}</ref> With the use of modern types of cranial drills, surgeons are able to create holes in the bone structure without traumatizing underlying brain tissue.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Liss |first1=Sam T. |title=Safe cranial drilling device |url=https://otd.harvard.edu/explore-innovation/technologies/safe-cranial-drilling-device/ |website=Harvard Office of Technology Development |access-date=10 November 2018}}</ref> The drill's working tooltip consists of a spiral blade that is framed by a guard device with an angled cranium guide that rests against the inner layer of the skull bone. The dura guard pushes the dura mater downward while the craniotome is moved forward thus preventing dural tearing.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Rogers |first1=Laurel |last2=Lancaster |first2=Ron |title=Patent US6506199B2 |url=https://patents.google.com/patent/US6506199B2/en |website=Google Patents |access-date=25 November 2018}}</ref> |

||

== Types and design == |

== Types and design == |

||

A cranial drill is an essential instrument used by surgeons to drill into the skull bone. |

|||

Various types of drills are used by surgeons for the craniotomy, or [[Oral and maxillofacial surgery|oral surgeries]]. The cranial drill can be differentiated by the examinations of what kind of surgery have to be performed. They can be manually operated, operated by electricity, or by [[pneumatic motor]]s. |

|||

=== Manual cranial drill === |

=== Manual cranial drill === |

||

[[File:Vilebrequin - musée HCL - instruments chirurgicaux.jpg|thumb|Vilebrequin - ''Musée des Hospices civils de Lyon'', Manual drill]] |

[[File:Vilebrequin - musée HCL - instruments chirurgicaux.jpg|thumb|Vilebrequin - ''Musée des Hospices civils de Lyon'', Manual drill]] |

||

The rotating crank is typically connected to several cogs that |

The rotating crank is typically connected to several cogs that set pressure on the skull. This specific drill is not connected to any external power and is used very little in today's operations.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Treccani |title=Trapano |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/trapano/ |website=Treccani enciclopedia on line |access-date=9 October 2018}}</ref> The manual cranial drill is the most used and predominant type of drill in [[surgery]], and performs manually. It has an adjusted stopper based on the setting and where the bone is thickest to prevent plunging. Surgeons use this drill manually without any other procedures, and can require substantial upper-body strength. |

||

=== Electric cranial drill === |

=== Electric cranial drill === |

||

The electric cranial drill is powered either by a battery or by [[electricity]] via [[ |

The electric cranial drill is powered either by a battery or by [[electricity]] via [[wall socket]]s. |

||

=== Pneumatic cranial drill === |

=== Pneumatic cranial drill === |

||

The [[pneumatic motor]] is known for its great speed, which makes surgery much easier and faster. It is driven by expanding compressed air. The use of this kind of mechanism has many advantages such as the ease of use through high peak velocities. Thanks to superior torque, this system has great performance and it is essential for complex revision operations. The surgical procedure is shorter than usual, so patients spend less time under [[anesthesia]].<ref name="SRM University">{{cite web |last1=SRM University |title=Surgical driller |url=http://www.srmuniv.ac.in/sites/default/files/downloads/surgical_driller.pdf |access-date=10 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181201005214/http://www.srmuniv.ac.in/sites/default/files/downloads/surgical_driller.pdf |archive-date=1 December 2018 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Pneumatic high-speed craniotomes usually run at 40,000 to 80,000 rpm and have greatly facilitated intracranial approaches in [[neurosurgery]]. They are also employed to temporarily remove the [[vertebral arch]] in [[laminotomy]].<ref name="SRM University" /> |

|||

==Scientific progress== |

==Scientific progress== |

||

| Line 62: | Line 49: | ||

===CAD/CAM=== |

===CAD/CAM=== |

||

[[CAD/CAM]] stands for ''computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing''. |

[[CAD/CAM]] stands for ''computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing''. In the medical field, as well, it is used by surgeons to simplify and ease surgeries: in the case of trepanning, a processor collects information from [[2D computer graphics|2D]] images and then turns them into [[3D computer graphics|3D]] images. The processor codifies this information so that the drill can, without any trouble, pierce the correct portion of the skull.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Couldwell |first1=William T. |last2=MacDonald |first2=Joel D. |last3=Thomas |first3=Charles L. |last4=Hansen |first4=Bradley C. |last5=Lapalikar |first5=Aniruddha |last6=Thakkar |first6=Bharat |last7=Balaji |first7=Alagar K. |title=Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing skull base drill |url=https://thejns.org/focus/view/journals/neurosurg-focus/42/5/article-pE6.xml |journal=Neurosurgical Focus |year=2017 |volume=42 |issue=5 |pages=E6 |doi=10.3171/2017.2.FOCUS16561 |pmid=28463621 |access-date=19 November 2018|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

||

===In movies=== |

|||

*''[[Saw 3]]'' : A craniotomy has been performed on John in order to relieve the pressure on his brain. The drill used in one of the scenes is not the one applied in surgeries. |

|||

*''[[Autopsy (2008 film)|Autopsy]]'' : The surgeons attempts to cut into a girl's skull with a manual drill, while [[classical music]] is played in the back by a turntable. |

|||

*''[[Frankenhooker]]'' : In one of the scenes, one of the characters drills a hole in his skull by himself with a conventional drill( not with a normal cranial drill). |

|||

*''[[Pi (film)|Pi]]'' : In the final scene, Max performs a trepanation on him self, towards the end of the act blood splatters all over the mirror. |

|||

*''[[Prison Break]]'' : During the fourth episode of the TV series Michael, one of the main characters, becomes ill. In order to cure his illness a operation to the skull is much need. The surgical operation is being operated with help of advanced, high end technologies. The intervention is shown during the 15th episode [[Going Under (Prison Break)]]. <ref>{{cite web |title=Going Under (episode) |url=https://prisonbreak.fandom.com/wiki/Going_Under_(episode) |website=FANDOM |accessdate=30 November 2018}}</ref> |

|||

*''[[Grey's Anatomy]]'': During the episode [[Almost Grown (Grey's Anatomy) ]] Meredith performs a craniotomy without any assistance from others around her on a patient. That same patient was previously cured by Lexie. |

|||

*''[[House M.D.]]'': In one of the scenes to be specific, season 3, episode 14 a hole is drilled into the skull of one of the patients to examine her [[Genetic disorder|genetic defect.]] Which she didn't feel any pain while the producer.<ref>{{cite |title=Insensitive. ''House, Season 3, Episode 14. Air date 13 February 2007''}}</ref> |

|||

===In books=== |

|||

*''Uncertainties, Mysteries, Doubts: Romanticism and the analytic attitude'': In this specific novel it states the importance of a cranial drill. In one specific an unexpected graphic animation and good nature came up which he becomes tense, full of miserable thoughts. Through his reasoning he looses hope and thinks " of all the devils of migraine" drilling and smashing into his brain or skull with a cranial. Right after the graphic and intense event occurred his head drops on his chests.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Snell |first1=Robert |title=Uncertainties, Mysteries, Doubts: Romanticism and the analytic attitude |publisher=Routledge,2012 |isbn=1136205195 |page=153}}</ref> |

|||

== Photo gallery == |

== Photo gallery == |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

File:Brace and bit cranial trephine, Germany, 1701-1800 Wellcome L0058144.jpg|Manual drill during the 18th century |

File:Brace and bit cranial trephine, Germany, 1701-1800 Wellcome L0058144.jpg|Manual drill during the 18th century |

||

File:Edinburgh Skull, trepanning showing hole in back of skull Wellcome M0009393.jpg|Edinburgh Skull, |

File:Edinburgh Skull, trepanning showing hole in back of skull Wellcome M0009393.jpg|Edinburgh Skull, showing trepanning hole in back of skull |

||

File:A human skull showing signs of Trepanning. Wellcome L0035690.jpg|A human skull showing signs of |

File:A human skull showing signs of Trepanning. Wellcome L0035690.jpg|A human skull showing signs of trepanning |

||

File:KMH - Trepanation.jpg|Human skull with trepanation, Celtic museum in Hallein (Salzburg) |

|||

File:Peter Treveris - engraving of Trepanation for Handywarke of surgeri 1525.png|Engraving by Peter Treveris of a trepanation. From Heironymus von Braunschweig's ''Handywarke of surgeri'' |

File:Peter Treveris - engraving of Trepanation for Handywarke of surgeri 1525.png|Engraving by Peter Treveris of a trepanation. From Heironymus von Braunschweig's ''Handywarke of surgeri'' |

||

File:Trepanation illustration France 1800s.jpg|Trepanation illustration France 1800s |

|||

File:Cranial trephine with two bits, Europe, 1601-1800 Wellcome L0058141.jpg|Cranial trephine with two bits, Europe, |

File:Cranial trephine with two bits, Europe, 1601-1800 Wellcome L0058141.jpg|Cranial trephine with two bits, Europe, 1601–1800 |

||

File:Decompressive Craniectomy.png|Decompressive Craniectomy |

File:Decompressive Craniectomy.png|Decompressive Craniectomy |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[ |

* [[Deep brain stimulation]] |

||

* [[Trepanning]] |

|||

* [[Instruments used in general surgery]] |

* [[Instruments used in general surgery]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Intracranial pressure]] |

||

* [[Retractor (medical)]] |

* [[Retractor (medical)]] |

||

* [[Surgical scissors]] |

* [[Surgical scissors]] |

||

* [[Deep brain stimulation]] |

|||

* [[Intracranial pressure]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

<!-- Inline citations added to your article will automatically display here. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WP:REFB for instructions on how to add citations. --> |

|||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

{{Surgical instruments|state=autocollapse}} |

{{Surgical instruments|state=autocollapse}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Medical equipment]] |

[[Category:Medical equipment]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Surgical instruments]] |

[[Category:Surgical instruments]] |

||

Latest revision as of 07:57, 11 September 2024

High-speed pneumatic surgical drill with cranial drill bit | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

Activity sectors | Surgery, craniotomy, craniectomy |

| Description | |

Fields of employment | Hospitals, clinics, emergency medicine |

A cranial drill, also known as a craniotome, is a tool for drilling simple burr holes (trepanation) or for creating larger openings in the skull. This exposes the brain and allows operations like craniotomy and craniectomy to be done. The drill itself can be manually or electrically driven, and primarily consists of a handpiece and a drill bit which is a sharp tool that has a form similar to Archimedes' screw, this instrument must be inserted into the drill chuck to perform holes and remove materials. The trepanation tool is generally equipped with a clutch which automatically disengages once it touches a softer tissue, thus preventing tears in the dura mater. For larger openings, the craniotome is an instrument that has replaced manually pulled saw wires in craniotomies from the 1980s.

History

[edit]Cranial drill

[edit]The oldest evidence of a hole being applied on a human's brain with a drill dates from c. 4000 B.C.[1] The oldest cranial drilling instrument was found in France, and subsequent use was evidenced by the Ancient Romans, Egyptians, and in Trepanation in Mesoamerica. The practice of trepanning is also evidenced in Ancient Greece, North and South America, Africa, Polynesia and the Far East. The conceivable reasons why ancient humans developed the technique of drilling the head could be religious, ritual or medical factors.[2] The first trepanning procedure consisted of different types of tools and techniques: at the beginning the only material that was available for use, it was a sharp and carved rock. The development of The Hippocratic Corpus, written in the fifth century B.C., is the first written source that can be found about trepanning. The aim of the procedure described in "On Wounds in the Head" was to allow the stagnant blood to escape from the head through a hole. The drill that was used at the time is similar to modern ones but was operated by hand rotation.[3]

In the 15th century, people began to believe that drilling was a cure for mental problems due to a magical stone of madness or stone of folly in the head, which had to be removed. Paintings that portray this practice exist, the most significant ones include The Extraction of the Stone of Madness c. 1488–1516 by Hieronymus Bosch and A Surgeon Extracting the Stone of Folly by Pieter Huys.[4]

From the Renaissance ages, cranial drilling continued to evolve and surgical practice was used less due to the high mortality rate. It was used only for some interventions, such as the treatment of hemorrhages, depressed fractures and penetrating the head. Also, the name for the surgery changed from trepanning to craniotomy.

In the late 1860s, the archaeologist E.G. Squier discovered a skull in an ancient Inca cemetery. This specific skull was anticipated to be of the pre-Columbian era. The skull exhibited a large rectangle-shaped hole on the top. The skull was brought it back to the United States, and his findings were presented to the New York Academy of Medicine. Squier argued that the brain was injected with a tool called a burin which was used on woods and metals before. Traces showed human hand prints. He concluded that the skull and brain evidenced recovery from prehistoric brain surgery, potentially prolonging the patient's life.[5]

Metallurgy was a technique that allowed the use of saws and scalpels. Other cultures came about experimenting through the usage of glass.[4]

Application

[edit]A cranial drill is currently used for neurosurgery operations. The procedure of trepanning is applied to patients who suffer for example a traumatic brain injury or a stroke. In these cases, it might be necessary to drill a hole in the skull to be able to access the dura mater or the brain itself, and to relieve brain pressure or blood clots.[6] With the use of modern types of cranial drills, surgeons are able to create holes in the bone structure without traumatizing underlying brain tissue.[7] The drill's working tooltip consists of a spiral blade that is framed by a guard device with an angled cranium guide that rests against the inner layer of the skull bone. The dura guard pushes the dura mater downward while the craniotome is moved forward thus preventing dural tearing.[8]

Types and design

[edit]A cranial drill is an essential instrument used by surgeons to drill into the skull bone. Various types of drills are used by surgeons for the craniotomy, or oral surgeries. The cranial drill can be differentiated by the examinations of what kind of surgery have to be performed. They can be manually operated, operated by electricity, or by pneumatic motors.

Manual cranial drill

[edit]

The rotating crank is typically connected to several cogs that set pressure on the skull. This specific drill is not connected to any external power and is used very little in today's operations.[9] The manual cranial drill is the most used and predominant type of drill in surgery, and performs manually. It has an adjusted stopper based on the setting and where the bone is thickest to prevent plunging. Surgeons use this drill manually without any other procedures, and can require substantial upper-body strength.

Electric cranial drill

[edit]The electric cranial drill is powered either by a battery or by electricity via wall sockets.

Pneumatic cranial drill

[edit]The pneumatic motor is known for its great speed, which makes surgery much easier and faster. It is driven by expanding compressed air. The use of this kind of mechanism has many advantages such as the ease of use through high peak velocities. Thanks to superior torque, this system has great performance and it is essential for complex revision operations. The surgical procedure is shorter than usual, so patients spend less time under anesthesia.[10] Pneumatic high-speed craniotomes usually run at 40,000 to 80,000 rpm and have greatly facilitated intracranial approaches in neurosurgery. They are also employed to temporarily remove the vertebral arch in laminotomy.[10]

Scientific progress

[edit]Technological progress to reduce surgery time and minimize risks for patients during surgery have been introduced in the field of cranial drills, primarily from machining.

CAD/CAM

[edit]CAD/CAM stands for computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing. In the medical field, as well, it is used by surgeons to simplify and ease surgeries: in the case of trepanning, a processor collects information from 2D images and then turns them into 3D images. The processor codifies this information so that the drill can, without any trouble, pierce the correct portion of the skull.[11]

Photo gallery

[edit]-

Manual drill during the 18th century

-

Edinburgh Skull, showing trepanning hole in back of skull

-

A human skull showing signs of trepanning

-

Human skull with trepanation, Celtic museum in Hallein (Salzburg)

-

Engraving by Peter Treveris of a trepanation. From Heironymus von Braunschweig's Handywarke of surgeri

-

Trepanation illustration France 1800s

-

Cranial trephine with two bits, Europe, 1601–1800

-

Decompressive Craniectomy

See also

[edit]- Deep brain stimulation

- Instruments used in general surgery

- Intracranial pressure

- Retractor (medical)

- Surgical scissors

References

[edit]- ^ Cohut, Maria (12 June 2018). "Skull-drilling: The ancient roots of modern neurosurgery". Medical News Today. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ Wylie, Robin. "Why our ancestors drilled holes in each other's skulls". BBC. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Gross, Charles G. "Trepanation from the Paleolothic to the internet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ a b Ferreira, Becky. "Madness Stones to New Age Medicine: A History of Drilling Holes in Our Heads". Motherboard. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Fawcett, Kristin (January 2016). "Trepanation: The History of One of the World's Oldest Surgeries". MentalFloss. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ "Trepanation". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Liss, Sam T. "Safe cranial drilling device". Harvard Office of Technology Development. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Rogers, Laurel; Lancaster, Ron. "Patent US6506199B2". Google Patents. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ^ Treccani. "Trapano". Treccani enciclopedia on line. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ a b SRM University. "Surgical driller" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ Couldwell, William T.; MacDonald, Joel D.; Thomas, Charles L.; Hansen, Bradley C.; Lapalikar, Aniruddha; Thakkar, Bharat; Balaji, Alagar K. (2017). "Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing skull base drill". Neurosurgical Focus. 42 (5): E6. doi:10.3171/2017.2.FOCUS16561. PMID 28463621. Retrieved 19 November 2018.