Napier Sabre: Difference between revisions

Sam Hocevar (talk | contribs) m spelling |

|||

| (370 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|1930s British aircraft piston engine}} |

|||

The '''Sabre''' was a 24-cylinder [[sleeve valve]] [[piston]] [[aircraft engine]] built by [[Napier & Son]] during [[WWII]]. It was one of the most powerful piston aircraft engines in the world, especially for [[inline engine|inline]] designs, developing over 3,500 [[horsepower]] (2,200 kW) in its later versions. However, the rapid conversion to [[jet engine]]s after the war led to the quick demise of the Sabre, as Napier also turned to jets. |

|||

<!-- This article is a part of [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Aircraft]]. Please see [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Aircraft/page content]] for recommended layout. --> |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2017}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=December 2017}} |

|||

{| {{Infobox aircraft begin |

|||

|name = Sabre |

|||

|image = Napier Sabre01.jpg |

|||

|caption = Napier Sabre cutaway at the London Science Museum. |

|||

}}{{Infobox aircraft engine |

|||

|type=[[Coolant#Liquids|Liquid-cooled]] [[H engine|H-24]] [[sleeve valve]] [[Reciprocating engine|piston]] [[Aircraft engine|aero engine]] |

|||

|manufacturer=[[D. Napier & Son]] |

|||

|national origin=[[United Kingdom]] |

|||

|first run=January 1938 |

|||

|major applications= [[Hawker Tempest]] <br /> [[Hawker Typhoon]] <br /> [[Napier-Heston Racer]] |

|||

|number built = |

|||

|program cost = |

|||

|unit cost = |

|||

|developed from = |

|||

|variants with their own articles = |

|||

|developed into = |

|||

}} |

|||

|} |

|||

The '''Napier Sabre''' is a British [[H engine|H-24-cylinder]], [[coolant|liquid-cooled]], [[sleeve valve]], [[piston]] [[aircraft engine|aero engine]], designed by [[Frank Halford|Major Frank Halford]] and built by [[D. Napier & Son]] during [[World War II]]. The engine evolved to become one of the most powerful [[Inline engine (aviation)|inline]] piston aircraft engines in the world, developing from {{convert|2,200|hp|kW|abbr=on}} in its earlier versions to {{convert|3500|hp|abbr=on}} in late-model prototypes. |

|||

[[Image:Napier_Sabre01.jpg|400px|left]] |

|||

The first operational aircraft to be powered by the Sabre were the [[Hawker Typhoon]] and [[Hawker Tempest]]; the first aircraft powered by the Sabre was the [[Napier-Heston Racer]], which was designed to capture the world speed record.{{#tag:ref|The Napier-Heston Racer used the first production Sabre engine. The world-record contender crashed during early tests and the project was discontinued.|group=nb}} Other aircraft using the Sabre were early prototype and production variants of the [[Blackburn Firebrand]], the [[Martin-Baker MB 3]] prototype and a [[Hawker Sea Fury|Hawker Fury]] prototype. The rapid introduction of [[jet engine]]s after the war led to the quick demise of the Sabre, as there was less need for high power military piston aero engines and because Napier turned its attention to developing [[turboprop]] engines such as the [[Napier Naiad|Naiad]] and [[Napier Eland|Eland]]. |

|||

Prior to the Sabre, Napier had been working on large engines for some time. Their most famous was the [[Napier Lion|Lion]], which had been a very successful engine between the World Wars and which, in modified form, powered several of the [[Supermarine]] designs to the [[Schneider Trophy]] in [[1923]] and [[1927]]. By the late 1920s it was no longer competitive, and work started on replacements. |

|||

==Design and development== |

|||

They followed the Lion with two new [[H engine|H-block]] designs: an H-16 engine known as the [[Napier Rapier|Rapier]], and a H-24 known as the [[Napier Dagger|Dagger]]. The H-block has a compact layout, as it essentially consists of two horizontally opposed [[inline engine]]s lying one atop another. Since the cylinders are opposed, the motion in one is balanced by the opposite motion in the one on the opposite side, leading to smooth running. However, in these new designs, Napier oddly decided to use air cooling; in service, the rear cylinders proved to be impossible to cool properly, leading to terrible reliability problems. |

|||

Prior to the Sabre, Napier had been working on large aero engines for some time. Its most famous was the [[Napier Lion|Lion]], which had been a very successful engine between the World Wars and in modified form had powered several of the [[Supermarine]] [[Schneider Trophy]] competitors in 1923 and 1927, as well as several [[land speed record]] cars. By the late 1920s, the Lion was no longer competitive and work started on replacements. |

|||

Napier followed the Lion with two [[H engine|H-block]] designs: the H-16 [[Napier Rapier|Rapier]] and the H-24 [[Napier Dagger|Dagger]]. The H-block has a compact layout, consisting of two horizontally opposed engines, one atop or beside the other. Since the cylinders are opposed, the motion in one is balanced by the motion on the opposing side, eliminating both first order and second order vibration. In these new designs, Napier chose air cooling but in service, the rear cylinders proved to be impossible to cool properly, which made the engines unreliable. |

|||

During the [[1930s]], designers were looking to the future of engine development. Many studies showed the need for engines that could produce 1 hp per cubic inch (50 kW/L), in order to be able to provide the power needed to equip large aircraft which could carry enough fuel for long-range use. This design goal became known as the [[hyper engine]], and it was clear that this sort of performance would not be easy to achieve. A typical large engine of the era, the [[Pratt & Whitney]] R-1830 ''Twin Wasp'', developed about 1,200 hp (895 kW) from 1,820 in³ (30 L), so an advance of some 50% would be needed. This called for radical changes, and while many companies tried to build the hyper engine, none were successful. |

|||

===Genesis=== |

|||

In [[1927]] [[Harry Ricardo]], at the [[RAE]], published a seminal study on the concept of the [[sleeve valve]] engine. In it they essentially stated that traditional [[poppet valve]] engines would likely have a hard time producing much beyond 1,500 hp (1,100 kW), a figure many companies were eyeing for next generation engines. In order to pass this limit, the sleeve valve would have to be used in order to increase [[volumetric efficiency]]. In the mid-1930s, Napier set about developing the Dagger into the most powerful engine in the world, by redesigning it with the sleeve valve system and adding water cooling. The H-block layout's inherent balance allowed it to run at higher [[RPM]], to deliver more power from a smaller displacement (more bangs per second means more power delivered); the sleeve valve would allow these higher RPMs to be reached. |

|||

[[File:Napier-Heston racer.jpg|thumb|The first aircraft designed around the Sabre engine – the [[Napier-Heston Racer]] which crashed during early flight tests.]] |

|||

During the 1930s, studies showed the need for engines capable of developing one horsepower per cubic inch of displacement (about 45 kW/[[litre]]). Such power output was needed to propel aircraft large enough to carry large fuel loads for long range flights. A typical large engine of the era, the [[Pratt & Whitney R-1830]] ''Twin Wasp'', developed about {{convert|1,200|hp|kW|abbr=on}} from 1,830 [[cubic inch]]es (30 litres), so an advance of some 50 per cent would be needed. This called for radical changes and while many companies tried to build such an engine, none succeeded.{{Citation needed|date=March 2011}} |

|||

In 1927, [[Harry Ricardo]] published a study on the concept of the [[sleeve valve]] engine. In it, he wrote that traditional [[poppet valve]] engines would be unlikely to produce much more than {{convert|1,500|hp|kW|abbr=on}}, a figure that many companies were eyeing for next generation engines. To pass this limit, the sleeve valve would have to be used, to increase [[volumetric efficiency]], as well as to decrease the engine's sensitivity to detonation, which was prevalent with the poor quality, low-octane fuels in use at the time.<ref>Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 {{ISBN|978-0750917124}}, p.145</ref> Halford had worked for Ricardo 1919–1922 at its London office{{#tag:ref|21 Suffolk St, Westminster, London, a little cul-de-sac off Pall Mall East.|group=nb}} and Halford's 1923 office was in Ladbroke Grove, North Kensington, only a few miles from Ricardo, while Halford's 1929 office was even closer (700 yards),<ref>Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 {{ISBN|978-0750917124}}, p.103</ref><ref>Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford, Douglas Taylor, 1999,{{ISBN|1 872922 16 3}}, p.73</ref> and while in 1927 Ricardo started work with [[Bristol Aeroplane Company|Bristol Engines]] on a line of sleeve-valve designs,<ref>Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 {{ISBN|978-0750917124}}, p.186</ref> Halford started work with Napier,<ref>Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford, Douglas Taylor, 1999,{{ISBN|1 872922 16 3}}, p.81</ref> using the Dagger as the basis. The layout of the H-block, with its inherent balance and the Sabre's relatively short stroke, allowed it to run at a higher rate of rotation, to deliver more power from a smaller displacement, provided that good volumetric efficiency could be maintained (with better breathing), which sleeve valves could do.<ref>Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 {{ISBN|978-0750917124}}, p.187</ref> |

|||

The first Sabre engines were ready for running in January [[1938]], although at a severely limited 1,350 hp (1,000 kW). By March they were already passing tests at 2,050 hp (1,500 kW), and by June [[1940]] the first production-ready versions were delivering 2,200 hp (1,640 kW) from their 2,238 in³ (37 L), close enough to 1 hp/in³ (50 kW/L) to be the first hyper engine to actually work. By the end of the year, they were producing 2,400 hp (1,800 kW). To put this in perspective, the contemporary 1940 [[Rolls-Royce Merlin]] II was generating just over 1,000 hp (750 kW), and the most powerful engines in the world all developed around 1,200 hp (900 kW). |

|||

The Napier company decided first to develop a large 24 cylinder liquid–cooled engine, capable of producing at least {{convert|2,000|hp|kW|abbr=on}} in late 1935. Although the company continued with the opposed H layout of the Dagger, this new design positioned the cylinder blocks horizontally and it was to use sleeve valves.<ref name="Flight309">[F C Sheffield] 23 March 1944. "[http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1944/1944%20-%200072.html 2,200 h.p. Napier Sabre ]" ''Flight'', p. 309. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 9 November 2009.</ref> All of the accessories were grouped conveniently above and below the cylinder blocks, rather than being at the front and rear of the engine, as in most contemporary designs.<ref name="Flight309"/> |

|||

Problems started to appear as soon as volume production started. Up to that point the engines had been hand-assembled by Napier craftsmen, and it proved to be rather difficult to adapt it to assembly line production techniques. In particular, the sleeves tended to fail quite often, seizing the engine in the process. At that time [[Bristol Aircraft|Bristol]] were developing their own sleeve valve designs, and their [[Bristol Taurus|Taurus]] engine had the same bore. At first Bristol refused to work with Napier, but eventually, under intense pressure from the [[Air Ministry]], they relented, and the problems soon disappeared with the addition of Bristol's well-machined sleeves. |

|||

The Air Ministry supported the Sabre programme with a development order in 1937 for two reasons: to provide an alternative engine if the [[Rolls-Royce Vulture]] and the [[Bristol Centaurus]] failed as the next generation of high power engines and to keep Napier in the aero-engine industry.<ref>Industry and Air Power The Expansion Of British Aircraft Production 1935-1941, Sebastian Ritchie 2007, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, {{ISBN|0-7146-4343-2}}, p.140</ref> |

|||

Quality control also proved to be a serious problem. Engines were often delivered with improperly cleaned castings, broken piston rings, and machine cuttings left inside the engine. Mechanics were constantly overworked trying to keep Sabres running, and during cold weather they had to run them every two hours during the night so that they wouldn't seize up. These problems took too long to straighten out, and for many the engine started to attain a bad reputation. To make matters worse, mechanics and pilots were unfamiliar with the very different nature of this engine, and tended to blame the Sabre for problems which were caused by incorrect handling. This was all exacerbated by the representatives of the competing Rolls-Royce company, who had their own agenda. |

|||

The first Sabre engines were ready for testing in January 1938, although they were limited to {{convert|1,350|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. By March, they were passing tests at {{convert|2,050|hp|kW|abbr=on}} and by June 1940, when the Sabre passed the [[Air Ministry]]'s 100-hour test, the first production versions were delivering {{convert|2,200|hp|kW|abbr=on}} from their 2,238 cubic inch (37 litre) displacements.<ref name="Flight309"/> By the end of the year, they were producing {{convert|2,400|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. The contemporary 1940 [[Rolls-Royce Merlin]] II was generating just over {{convert|1,000|hp|kW|abbr=on}} from a 1,647 cubic inch (27 litre) displacement. |

|||

===Production=== |

|||

The problems were eventually addressed, however, and the engine started to reliably allow higher and higher boost settings. By 1944 the Sabre V was delivering 2,400 hp (1,800 kW) consistently, and the reputation of the engine started to improve. This was the last version to see service, however. The later Sabre VII delivered 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) with a new supercharger, and the final test articles delivered 4,000 hp (3,000 kW). By the end of the war there were several engines of the same power class; the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 ''Wasp Major'' was at that time producing about 3,055 hp (2,280 kW), but used over twice the displacement, at 4,360 in³ (71 L). |

|||

[[File:Hawker Typhoon 2 ExCC.jpg|thumb|The [[Hawker Typhoon]] was the first operational Sabre-powered aircraft, entering service with the RAF in mid-1941. Problems with both the Sabre engine and the airframe nearly led to the Typhoon's withdrawal from service.]] |

|||

Problems arose as soon as mass production began. Prototype engines had been hand-assembled by Napier craftsmen and it proved to be difficult to adapt it to assembly-line production techniques. The sleeves often failed due to the way they were manufactured from chrome-molybdenum steel, leading to seized cylinders, which caused the loss of the sole prototype [[Martin-Baker MB 3]].<ref name="Flinov45">Flight 1945, p.550.</ref><ref>Aeroplane 2010, pp. 65–66.</ref> The Ministry of Aircraft Production was responsible for the development of the engine and arranged for sleeves to be machined by the [[Bristol Aeroplane Company]] from its Taurus engine forgings. These nitrided austenitic steel sleeves were the result of many years of intensive sleeve development, experience that Napier did not have. Air filters had to be fitted when a new sleeve problem appeared in 1944 when aircraft were operating from Normandy soil with its abrasive, gritty dust.<ref>I Kept No Diary-60 Years with Marine Diesels, Automobile and Aero Engines, F.R. Banks 1978, Airlife Publications, {{ISBN|0 9504543 9 7}}, p.133</ref> |

|||

Quality control proved to be inadequate, engines were often delivered with improperly cleaned castings, broken piston rings and machine cuttings left inside the engine.<ref name="tempest">[http://www.hawkertempest.se/NapierSabre1.htm Napier Sabre] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120623153341/http://www.hawkertempest.se/NapierSabre1.htm |date=23 June 2012 }} Retrieved on 17 July 2009.</ref> Mechanics were overworked trying to keep the Sabres running and during cold weather they had to run them every two hours during the night so that the engine oil would not congeal and prevent the engine from starting the next day.{{#tag:ref|Unlike current "multigrade" [[motor oil]]s, the lubricants in use in the 1940s thickened up at low temperatures, thus preventing the Sabre from "picking-up" when started.|group=nb}} These problems took too long to remedy and the engine gained a bad reputation. To make matters worse, mechanics and pilots unfamiliar with the different nature of the engine, tended to blame the Sabre for problems that were caused by not following correct procedures. This was exacerbated by the representatives of the competing Rolls-Royce company, which had its own agenda. In 1944, Rolls-Royce produced a similar design prototype called the [[Rolls-Royce Eagle (1944)|Eagle]]. |

|||

The Sabre's primary use was in the [[Hawker Typhoon]] and its derivative, the [[Hawker Tempest|Tempest]]. While the former was not the fastest plane in the air, the Sabre engine drove it past anything whilst flying at lower altitudes, where it could reach about 412 mph (663 km/h). At higher altitudes, the thick wing of the Typhoon made it slower, and so it was primarily used as a [[strike fighter]]. The later Tempest added a new low-drag wing, and the otherwise similar plane became the fastest [[propellor]]-driven fighter of the war, at least for a short time. |

|||

Napier seemed complacent and tinkered with the design for better performance. In 1942, it started a series of projects to improve its high-altitude performance, with the addition of a three-speed, two-stage [[supercharger]], when the basic engine was still not running reliably. In December 1942, the company was purchased by the [[English Electric|English Electric Company]], which ended the supercharger project immediately and devoted the whole company to solving the production problems, which was achieved quickly. |

|||

==== Specifications ==== |

|||

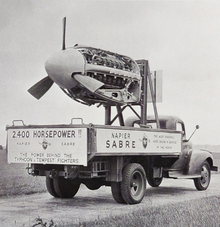

[[File:Napier Sabre on truck.png|thumb|A 2,400hp Sabre inside a mock-up of an aircraft nose, mounted on a truck for display purposes |alt=The truck has signs reading "2,400 Horsepower!! The power behind the Typhoon & Tempest fighters" and "Napier Sabre - The most powerful aero engine in service in the world", plus the Napier logo]] |

|||

For Napier Sabre II, the first production version: |

|||

By 1944, the Sabre V was delivering {{convert|2,400|hp|kW|abbr=off}} consistently and the reputation of the engine started to improve. This was the last version to enter service, being used in the [[Hawker Typhoon]] and its derivative, the [[Hawker Tempest]]. Without the advanced supercharger, the engine's performance over {{convert|20000|ft|m|abbr=on}} fell off rapidly and pilots flying Sabre-powered aircraft, were generally instructed to enter combat only below this altitude. At low altitude, both planes were formidable. As air superiority over Continental Europe was slowly gained, Typhoons were increasingly used as [[fighter-bomber]]s, notably by the [[RAF Second Tactical Air Force]]. The Tempest became the principal destroyer of the [[V-1 flying bomb]] ([[Fieseler Fi 103]]), since it was the fastest of all the Allied fighters at low levels. Later, the Tempest destroyed about 20 [[Messerschmitt Me 262]] jet aircraft. |

|||

:Bore by stroke: 5.0 by 4.75 in (127 by 121 mm) |

|||

:Displacement: 2,238 in³ (36.7L) |

|||

:Compression ratio: 7 to 1 |

|||

:Power: 2,180 hp (1,630 kW) at 3700 rpm |

|||

:Weight: 2360 lb (1,070 kg) |

|||

Development continued and the later Sabre VII delivered {{convert|3,500|hp|kW|abbr=on}} with a new supercharger. By the end of World War II, there were several engines in the same power class. The [[Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major]] four-row, 28-cylinder radial produced {{convert|3,000|hp|kW|abbr=on}} at first and later types produced {{convert|3,800|hp|kW|abbr=on}}, but these required almost twice the displacement in order to do so, 4,360 cubic inches (71 litres). |

|||

''References:'' |

|||

:[http://www.cpmac.com/~cmcgarry/napier/napierwelc.html Sabre Sleeve Valve Engine] |

|||

: LJK Setright: ''The power to fly: the development of the piston engine in aviation''. Allen & Unwin, 1971. |

|||

: Graham White: ''Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II'' . SAE, 1995. |

|||

{{airlistbox}} |

|||

==Variants== |

|||

[[Category:Aircraft piston engines]] |

|||

Note:{{#tag:ref|List from Lumsden unless otherwise noted.|group=nb}} |

|||

;Sabre I (E.107) |

|||

:(1939) {{convert|2,000|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. |

|||

;Sabre II |

|||

:(1940) {{convert|2,300|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Experimental 0.332:1 propeller reduction gear ratio. |

|||

;Sabre II (production variant) |

|||

:{{convert|2,200|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Reduction gear ratio 0.274:1: mainly used in early [[Hawker Typhoon]]s.<ref>Sheffield March 1944, p. 310.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre IIA |

|||

:{{convert|2,235|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Revised ignition system: maximum boost +9 lbs.<ref>Air Ministry 1943, pp. 24, 25.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre IIB |

|||

:{{convert|2,400|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Four choke [[SU Carburettor|S.U. carburettor]]: Mainly used in [[Hawker Tempest|Hawker Tempest V]].<ref name="Flight 1945, p. 551.">Flight 1945, p. 551.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre IIC |

|||

:{{convert|2,065|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Similar to Mk VII. |

|||

[[File:NapierSabreIII.JPG|thumb|right|Napier Sabre III]] |

|||

;Sabre III |

|||

:{{convert|2,250|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Similar to Mk IIA, tailored for the [[Blackburn Firebrand]]: 25 manufactured and installed.<ref name="Flight 1945, p. 551."/> |

|||

;Sabre IV |

|||

:{{convert|2,240|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. As Mk VA with Hobson fuel injection: preliminary flight development engine for Sabre V series.<ref name="Flight 1945, p. 551."/> Used in Hawker Tempest I.<ref>Mason 1991, p. 331.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre V |

|||

:{{convert|2,600|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Developed MK II, redesigned supercharger with increased boost, redesigned induction system. |

|||

;Sabre VA |

|||

:{{convert|2,600|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Mk V with Hobson-R.A.E fuel injection, single-lever throttle and propeller control: used in Hawker Tempest VI. |

|||

;Sabre VI |

|||

:{{convert|2,310|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Mk VA with [[Dowty Rotol|Rotol]] cooling fan: used in 2 Hawker Tempest Vs modified to use Napier designed annular radiators; also in experimental [[Vickers Warwick|Vickers Warwick V]].<ref>Flight 1946, p. 91.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre VII |

|||

:{{convert|3,055|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Mk VA strengthened to withstand high powers produced using [[Water injection (engines)|Water/Methanol injection]]. Larger supercharger impeller.<ref>Flight 1945, p. 552.</ref> |

|||

;Sabre VIII |

|||

:{{convert|3,000|hp|kW|abbr=on}}. Intended for [[Hawker Sea Fury|Hawker Fury]]; tested in the [[Folland Fo.108]]. |

|||

;Sabre E.118 |

|||

:(1941) Three-speed, two-stage supercharger, [[contra-rotating propeller]]; test flown in Fo.108. |

|||

;Sabre E.122 |

|||

:(1946) 3,500 horsepower. Intended for Napier 500mph tailless fighter |

|||

==Applications== |

|||

The engine has been used in many aircraft, including two mass-produced fighters.<ref>Application lists from Lumsden</ref> |

|||

===Adopted=== |

|||

* [[Hawker Tempest]] |

|||

* [[Hawker Typhoon]] |

|||

===Limited production and prototypes=== |

|||

* [[Blackburn Firebrand]], only in 21 early production aircraft |

|||

* [[Fairey Battle]], test-bed |

|||

* [[Folland Fo.108]], test-bed |

|||

* [[Hawker Sea Fury|Hawker Fury]], prototype (2 built (LA610, VP207), 485 mph) |

|||

* [[Martin-Baker MB 3]], prototype |

|||

* [[Napier-Heston Racer]], prototype |

|||

* [[Vickers Warwick]], prototype |

|||

==Restoration project and engines on display== |

|||

;Under restoration: |

|||

* [[Canadian Aviation Heritage Centre]], [[Macdonald Campus]], [[McGill University]], [[Montréal]].<ref>{{usurped|1=[https://web.archive.org/web/20080515144859/http://www.cahc-ccpa.com/workshop_one.htm CAHC "Workshop One"]}} Retrieved: 21 November 2009.</ref> |

|||

* Sabre IIa, Serial Number 2484, [[Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group]], RB396, UK |

|||

;Preserved on public display: |

|||

* [[Solent Sky]] (example on loan from [[Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry]]) |

|||

* [[Fantasy of Flight]], Polk City, Florida |

|||

* A Sabre IIA engine has been restored by the Friends Association of the [[Museo Nacional de Aeronáutica de Argentina]] and is on public display at the Engines Hall.{{citation needed|date=September 2015}} |

|||

;Sectioned Napier engines on public display: |

|||

* [[Imperial War Museum Duxford|Imperial War Museum]], [[Duxford]] (donated by [[Cambridge University Engineering Department]]) |

|||

* [[Royal Air Force Museum London]] |

|||

* [[Science Museum (London)|London Science Museum]] |

|||

* [[World of Wearable Art|World of WearableArt & Classic Cars Museum, Nelson]] |

|||

* [[Canada Aviation and Space Museum]], Ottawa |

|||

==Specifications (Sabre VA)== |

|||

{{pistonspecs |

|||

|<!-- If you do not understand how to use this template, please ask at [[Wikipedia talk:WikiProject Aircraft]] --> |

|||

<!-- Please include units where appropriate (main comes first, alt in parentheses). If data are missing, leave the parameter blank (do not delete it). For additional lines, end your alt units with </li> and start a new, fully-formatted line with <li> --> |

|||

|ref=''Lumsden''<ref>Lumsden 2003, p.176.</ref><ref>Flight 1945, pp. 550-553.</ref> |

|||

|type=24-cylinder supercharged liquid-cooled [[H engine|H-type]] aircraft piston engine |

|||

|bore={{convert|5.0|in|mm|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

|stroke={{convert|4.75|in|mm|0|abbr=on}} |

|||

|displacement={{convert|2,240|cuin|L|abbr=on}} |

|||

|length={{convert|82.25|in|mm|abbr=on}} |

|||

|diameter= |

|||

|width={{convert|40|in|mm|abbr=on}} |

|||

|height={{convert|46|in|mm|abbr=on}} |

|||

|weight={{convert|2,360|lb|kg}} |

|||

|valvetrain=[[Sleeve valve]] |

|||

|supercharger=[[Torsion (mechanics)|Torsion]] [[Drive shaft|shaft]] drive to gear-driven, single-stage, two-speed [[centrifugal type supercharger|centrifugal supercharger]] |

|||

|turbocharger= |

|||

|fuelsystem=[[Claudel-Hobson|Hobson-R.A.E]] injection-type [[carburetor|carburettor]] |

|||

|fueltype=100/130 [[octane rating|octane]] [[gasoline|petrol]] |

|||

|oilsystem=High pressure: [[Oil pump (internal combustion engine)|Oil pump]] and full flow [[oil filter]] with three scavenge pumps |

|||

|coolingsystem=Liquid cooled: 70% water and 30% [[ethylene glycol]] coolant mixture, pressurised. |

|||

|power= |

|||

* {{convert|2,850|hp|kW|abbr=on}} at 3,800 rpm and +13 psi (0.9 bar, 56") intake boost |

|||

* {{convert|3,040|hp|kW|abbr=on}} at 4,000 rpm [[war emergency power]] |

|||

|specpower=1.36 hp/in³ (59.9 kW/L) |

|||

|compression=7:1 |

|||

|fuelcon=117 gallons/hour (532 L/hr) at maximum cruise, F.S. supercharger gear; 241 gallons/hour (1,096 L/hr) at maximum combat rating, F.S. supercharger |

|||

|specfuelcon= |

|||

|oilcon= 47 pints/hour (27 L/hr) at maximum cruise 3,250 rpm and +7 psi (0.48 bar, 14"); 71 pints/hour (40 L/hr) at war emergency power |

|||

|power/weight=1.29 hp/lb (2.06 kW/kg) |

|||

}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{aircontent |

|||

<!-- other related articles that have not already linked: --> |

|||

|see also= |

|||

<!-- designs which were developed into or from this aircraft: --> |

|||

|related= |

|||

<!-- aircraft that are of similar role, era, and capability as this design: --> |

|||

|similar aircraft= |

|||

<!-- relevant lists that this aircraft appears in: --> |

|||

|lists= |

|||

* [[List of aircraft engines]] |

|||

<!-- For aircraft engine articles. Engines that are of similar to this design: --> |

|||

|similar engines= |

|||

* [[Daimler-Benz DB 604]] |

|||

* [[Dobrynin VD-4K]] |

|||

* [[Junkers Jumo 222]] |

|||

* [[Lycoming H-2470]] |

|||

* [[Pratt & Whitney X-1800]] |

|||

* [[Pratt & Whitney XH-3130]] |

|||

* [[Rolls-Royce Eagle (1944)|Rolls-Royce Eagle]] |

|||

* [[Wright R-2160 Tornado]] |

|||

<!-- See [[WP:Air/PC]] for more explanation of these fields. --> |

|||

}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Footnotes=== |

|||

{{reflist|group=nb}} |

|||

===Notes=== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

===Bibliography=== |

|||

* Air Ministry. ''Pilot's Notes for Typhoon Marks IA and IB; Sabre II or IIA engine (2nd edition)''. London: Crecy Publications, 2004. {{ISBN|0-85979-033-9}} |

|||

* "A Real Contender (article and images) " [http://www.aeroplanemonthly.co.uk/ Aeroplane] No. 452, Volume 38, Number 12, December 2010. |

|||

* [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1943/1943%20-%200955.html "A Co-operative Challenger (article and images on Heston Racer).]" ''[[Flight International|Flight and The Aircraft Engineer]]'' No. 1790, Volume XLIII, 15 April 1943. |

|||

* Gunston, Bill. ''World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines: From the Pioneers to the Present Day''. 5th edition, Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2006. {{ISBN|0-7509-4479-X}} |

|||

* Lumsden, Alec. ''British Piston Engines and Their Aircraft''. Marlborough, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. {{ISBN|1-85310-294-6}}. |

|||

* Mason, Francis K. ''Hawker Aircraft Since 1920 (3rd revised edition)''. London: Putnam, 1991. {{ISBN|0-85177-839-9}}. |

|||

* [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1945/1945%20-%202283.html "Napier Sabre VII (article and images).]" ''[[Flight International|Flight and The Aircraft Engineer]]'' No. 1926, Volume XLVIII, 22 November 1945. |

|||

* [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1946/1946%20-%201438.html "Napier Flight Development (article and images on Napier's test and development centre).]" ''[[Flight International|Flight and The Aircraft Engineer]]'' No. 1961, Volume L, 25 July 1946. |

|||

* [[L. J. K. Setright|Setright, L. J. K.]]: ''The Power to Fly: The Development of the Piston Engine in Aviation''. Allen & Unwin, 1971. {{ISBN|0-04-338041-7}}. |

|||

* Sheffield, F. C. [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1944/1944%20-%200072.html "2,200 h.p. Napier Sabre (article and images).]" ''[[Flight International|Flight and The Aircraft Engineer]]'' No. 1829, Volume XLV, 13 January 1944. |

|||

* Sheffield, F. C. [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1944/1944%20-%200603.html "Napier Sabre II (article and images).]" ''[[Flight International|Flight and The Aircraft Engineer]]'' No. 1839, Volume XLV, 23 March 1944. |

|||

* White, Graham. ''Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II: History and Development of Frontline Aircraft Piston Engines Produced by Great Britain and the United States During World War II''. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 1995. {{ISBN|1-56091-655-9}} |

|||

* Reynolds, John. ''Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo''. Stroud, UK: Sutton, 1999. {{ISBN|978-0750917124}} |

|||

* Taylor, Douglas. ''Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford''. Derby, UK: RRHT, 1999. {{ISBN|1 872922 16 3}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* {{Ref Jane's|||1945}} {{ISBN|0-517-67964-7}} (1989 copy by Crescent Books, NY.) |

|||

* [[Pierre Clostermann|Clostermann, Pierre]]: ''The Big Show''. London, UK: Chatto & Windus in association with William Heinemann, 1953. {{ISBN|0-297-84619-1}} (2004 edition). |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category}} |

|||

* [http://www.npht.org/ Napier Power Heritage Trust site] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120409202601/http://www.khulsey.com/makoto_ouchi_napier_sabre.html Cutaway illustration of a Napier Sabre drawn by Max Millar (uncredited) and coloured in by Makoto Oiuchi] |

|||

* [http://www.airracinghistory.freeola.com/aircraft/Napier-Heston%20Racer.htm The Sabre-powered Napier-Heston Racer] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120623153341/http://www.hawkertempest.se/NapierSabre1.htm The Hawker Tempest Page] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20090430152818/http://www.hawkertempest.se/Stories.htm The Greatest Engines of All Time] |

|||

* [http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1946/1946%20-%201973.html ''NAPIER SABRE 3000 B.H.P''] A 1946 ''[[Flight International|Flight]]'' advertisement for the Sabre engine |

|||

{{Napierengines}} |

|||

[[Category:Napier aircraft engines|Sabre]] |

|||

[[Category:Sleeve valve engines]] |

|||

[[Category:Boxer engines]] |

|||

[[Category:1930s aircraft piston engines]] |

|||

[[Category:H engines]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 00:17, 23 September 2024

| Sabre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Napier Sabre cutaway at the London Science Museum. | |

| Type | Liquid-cooled H-24 sleeve valve piston aero engine |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | D. Napier & Son |

| First run | January 1938 |

| Major applications | Hawker Tempest Hawker Typhoon Napier-Heston Racer |

The Napier Sabre is a British H-24-cylinder, liquid-cooled, sleeve valve, piston aero engine, designed by Major Frank Halford and built by D. Napier & Son during World War II. The engine evolved to become one of the most powerful inline piston aircraft engines in the world, developing from 2,200 hp (1,600 kW) in its earlier versions to 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) in late-model prototypes.

The first operational aircraft to be powered by the Sabre were the Hawker Typhoon and Hawker Tempest; the first aircraft powered by the Sabre was the Napier-Heston Racer, which was designed to capture the world speed record.[nb 1] Other aircraft using the Sabre were early prototype and production variants of the Blackburn Firebrand, the Martin-Baker MB 3 prototype and a Hawker Fury prototype. The rapid introduction of jet engines after the war led to the quick demise of the Sabre, as there was less need for high power military piston aero engines and because Napier turned its attention to developing turboprop engines such as the Naiad and Eland.

Design and development

[edit]Prior to the Sabre, Napier had been working on large aero engines for some time. Its most famous was the Lion, which had been a very successful engine between the World Wars and in modified form had powered several of the Supermarine Schneider Trophy competitors in 1923 and 1927, as well as several land speed record cars. By the late 1920s, the Lion was no longer competitive and work started on replacements.

Napier followed the Lion with two H-block designs: the H-16 Rapier and the H-24 Dagger. The H-block has a compact layout, consisting of two horizontally opposed engines, one atop or beside the other. Since the cylinders are opposed, the motion in one is balanced by the motion on the opposing side, eliminating both first order and second order vibration. In these new designs, Napier chose air cooling but in service, the rear cylinders proved to be impossible to cool properly, which made the engines unreliable.

Genesis

[edit]

During the 1930s, studies showed the need for engines capable of developing one horsepower per cubic inch of displacement (about 45 kW/litre). Such power output was needed to propel aircraft large enough to carry large fuel loads for long range flights. A typical large engine of the era, the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp, developed about 1,200 hp (890 kW) from 1,830 cubic inches (30 litres), so an advance of some 50 per cent would be needed. This called for radical changes and while many companies tried to build such an engine, none succeeded.[citation needed]

In 1927, Harry Ricardo published a study on the concept of the sleeve valve engine. In it, he wrote that traditional poppet valve engines would be unlikely to produce much more than 1,500 hp (1,100 kW), a figure that many companies were eyeing for next generation engines. To pass this limit, the sleeve valve would have to be used, to increase volumetric efficiency, as well as to decrease the engine's sensitivity to detonation, which was prevalent with the poor quality, low-octane fuels in use at the time.[1] Halford had worked for Ricardo 1919–1922 at its London office[nb 2] and Halford's 1923 office was in Ladbroke Grove, North Kensington, only a few miles from Ricardo, while Halford's 1929 office was even closer (700 yards),[2][3] and while in 1927 Ricardo started work with Bristol Engines on a line of sleeve-valve designs,[4] Halford started work with Napier,[5] using the Dagger as the basis. The layout of the H-block, with its inherent balance and the Sabre's relatively short stroke, allowed it to run at a higher rate of rotation, to deliver more power from a smaller displacement, provided that good volumetric efficiency could be maintained (with better breathing), which sleeve valves could do.[6]

The Napier company decided first to develop a large 24 cylinder liquid–cooled engine, capable of producing at least 2,000 hp (1,500 kW) in late 1935. Although the company continued with the opposed H layout of the Dagger, this new design positioned the cylinder blocks horizontally and it was to use sleeve valves.[7] All of the accessories were grouped conveniently above and below the cylinder blocks, rather than being at the front and rear of the engine, as in most contemporary designs.[7]

The Air Ministry supported the Sabre programme with a development order in 1937 for two reasons: to provide an alternative engine if the Rolls-Royce Vulture and the Bristol Centaurus failed as the next generation of high power engines and to keep Napier in the aero-engine industry.[8] The first Sabre engines were ready for testing in January 1938, although they were limited to 1,350 hp (1,010 kW). By March, they were passing tests at 2,050 hp (1,530 kW) and by June 1940, when the Sabre passed the Air Ministry's 100-hour test, the first production versions were delivering 2,200 hp (1,600 kW) from their 2,238 cubic inch (37 litre) displacements.[7] By the end of the year, they were producing 2,400 hp (1,800 kW). The contemporary 1940 Rolls-Royce Merlin II was generating just over 1,000 hp (750 kW) from a 1,647 cubic inch (27 litre) displacement.

Production

[edit]

Problems arose as soon as mass production began. Prototype engines had been hand-assembled by Napier craftsmen and it proved to be difficult to adapt it to assembly-line production techniques. The sleeves often failed due to the way they were manufactured from chrome-molybdenum steel, leading to seized cylinders, which caused the loss of the sole prototype Martin-Baker MB 3.[9][10] The Ministry of Aircraft Production was responsible for the development of the engine and arranged for sleeves to be machined by the Bristol Aeroplane Company from its Taurus engine forgings. These nitrided austenitic steel sleeves were the result of many years of intensive sleeve development, experience that Napier did not have. Air filters had to be fitted when a new sleeve problem appeared in 1944 when aircraft were operating from Normandy soil with its abrasive, gritty dust.[11]

Quality control proved to be inadequate, engines were often delivered with improperly cleaned castings, broken piston rings and machine cuttings left inside the engine.[12] Mechanics were overworked trying to keep the Sabres running and during cold weather they had to run them every two hours during the night so that the engine oil would not congeal and prevent the engine from starting the next day.[nb 3] These problems took too long to remedy and the engine gained a bad reputation. To make matters worse, mechanics and pilots unfamiliar with the different nature of the engine, tended to blame the Sabre for problems that were caused by not following correct procedures. This was exacerbated by the representatives of the competing Rolls-Royce company, which had its own agenda. In 1944, Rolls-Royce produced a similar design prototype called the Eagle.

Napier seemed complacent and tinkered with the design for better performance. In 1942, it started a series of projects to improve its high-altitude performance, with the addition of a three-speed, two-stage supercharger, when the basic engine was still not running reliably. In December 1942, the company was purchased by the English Electric Company, which ended the supercharger project immediately and devoted the whole company to solving the production problems, which was achieved quickly.

By 1944, the Sabre V was delivering 2,400 horsepower (1,800 kilowatts) consistently and the reputation of the engine started to improve. This was the last version to enter service, being used in the Hawker Typhoon and its derivative, the Hawker Tempest. Without the advanced supercharger, the engine's performance over 20,000 ft (6,100 m) fell off rapidly and pilots flying Sabre-powered aircraft, were generally instructed to enter combat only below this altitude. At low altitude, both planes were formidable. As air superiority over Continental Europe was slowly gained, Typhoons were increasingly used as fighter-bombers, notably by the RAF Second Tactical Air Force. The Tempest became the principal destroyer of the V-1 flying bomb (Fieseler Fi 103), since it was the fastest of all the Allied fighters at low levels. Later, the Tempest destroyed about 20 Messerschmitt Me 262 jet aircraft.

Development continued and the later Sabre VII delivered 3,500 hp (2,600 kW) with a new supercharger. By the end of World War II, there were several engines in the same power class. The Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major four-row, 28-cylinder radial produced 3,000 hp (2,200 kW) at first and later types produced 3,800 hp (2,800 kW), but these required almost twice the displacement in order to do so, 4,360 cubic inches (71 litres).

Variants

[edit]Note:[nb 4]

- Sabre I (E.107)

- (1939) 2,000 hp (1,500 kW).

- Sabre II

- (1940) 2,300 hp (1,700 kW). Experimental 0.332:1 propeller reduction gear ratio.

- Sabre II (production variant)

- 2,200 hp (1,600 kW). Reduction gear ratio 0.274:1: mainly used in early Hawker Typhoons.[13]

- Sabre IIA

- 2,235 hp (1,667 kW). Revised ignition system: maximum boost +9 lbs.[14]

- Sabre IIB

- 2,400 hp (1,800 kW). Four choke S.U. carburettor: Mainly used in Hawker Tempest V.[15]

- Sabre IIC

- 2,065 hp (1,540 kW). Similar to Mk VII.

- Sabre III

- 2,250 hp (1,680 kW). Similar to Mk IIA, tailored for the Blackburn Firebrand: 25 manufactured and installed.[15]

- Sabre IV

- 2,240 hp (1,670 kW). As Mk VA with Hobson fuel injection: preliminary flight development engine for Sabre V series.[15] Used in Hawker Tempest I.[16]

- Sabre V

- 2,600 hp (1,900 kW). Developed MK II, redesigned supercharger with increased boost, redesigned induction system.

- Sabre VA

- 2,600 hp (1,900 kW). Mk V with Hobson-R.A.E fuel injection, single-lever throttle and propeller control: used in Hawker Tempest VI.

- Sabre VI

- 2,310 hp (1,720 kW). Mk VA with Rotol cooling fan: used in 2 Hawker Tempest Vs modified to use Napier designed annular radiators; also in experimental Vickers Warwick V.[17]

- Sabre VII

- 3,055 hp (2,278 kW). Mk VA strengthened to withstand high powers produced using Water/Methanol injection. Larger supercharger impeller.[18]

- Sabre VIII

- 3,000 hp (2,200 kW). Intended for Hawker Fury; tested in the Folland Fo.108.

- Sabre E.118

- (1941) Three-speed, two-stage supercharger, contra-rotating propeller; test flown in Fo.108.

- Sabre E.122

- (1946) 3,500 horsepower. Intended for Napier 500mph tailless fighter

Applications

[edit]The engine has been used in many aircraft, including two mass-produced fighters.[19]

Adopted

[edit]Limited production and prototypes

[edit]- Blackburn Firebrand, only in 21 early production aircraft

- Fairey Battle, test-bed

- Folland Fo.108, test-bed

- Hawker Fury, prototype (2 built (LA610, VP207), 485 mph)

- Martin-Baker MB 3, prototype

- Napier-Heston Racer, prototype

- Vickers Warwick, prototype

Restoration project and engines on display

[edit]- Under restoration

- Canadian Aviation Heritage Centre, Macdonald Campus, McGill University, Montréal.[20]

- Sabre IIa, Serial Number 2484, Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group, RB396, UK

- Preserved on public display

- Solent Sky (example on loan from Birmingham Museum of Science and Industry)

- Fantasy of Flight, Polk City, Florida

- A Sabre IIA engine has been restored by the Friends Association of the Museo Nacional de Aeronáutica de Argentina and is on public display at the Engines Hall.[citation needed]

- Sectioned Napier engines on public display

- Imperial War Museum, Duxford (donated by Cambridge University Engineering Department)

- Royal Air Force Museum London

- London Science Museum

- World of WearableArt & Classic Cars Museum, Nelson

- Canada Aviation and Space Museum, Ottawa

Specifications (Sabre VA)

[edit]General characteristics

- Type: 24-cylinder supercharged liquid-cooled H-type aircraft piston engine

- Bore: 5.0 in (127 mm)

- Stroke: 4.75 in (121 mm)

- Displacement: 2,240 cu in (36.7 L)

- Length: 82.25 in (2,089 mm)

- Width: 40 in (1,000 mm)

- Height: 46 in (1,200 mm)

- Dry weight: 2,360 pounds (1,070 kg)

Components

- Valvetrain: Sleeve valve

- Supercharger: Torsion shaft drive to gear-driven, single-stage, two-speed centrifugal supercharger

- Fuel system: Hobson-R.A.E injection-type carburettor

- Fuel type: 100/130 octane petrol

- Oil system: High pressure: Oil pump and full flow oil filter with three scavenge pumps

- Cooling system: Liquid cooled: 70% water and 30% ethylene glycol coolant mixture, pressurised.

Performance

- Power output: * 2,850 hp (2,130 kW) at 3,800 rpm and +13 psi (0.9 bar, 56") intake boost

- 3,040 hp (2,270 kW) at 4,000 rpm war emergency power

- Specific power: 1.36 hp/in³ (59.9 kW/L)

- Compression ratio: 7:1

- Fuel consumption: 117 gallons/hour (532 L/hr) at maximum cruise, F.S. supercharger gear; 241 gallons/hour (1,096 L/hr) at maximum combat rating, F.S. supercharger

- Oil consumption: 47 pints/hour (27 L/hr) at maximum cruise 3,250 rpm and +7 psi (0.48 bar, 14"); 71 pints/hour (40 L/hr) at war emergency power

- Power-to-weight ratio: 1.29 hp/lb (2.06 kW/kg)

See also

[edit]Comparable engines

- Daimler-Benz DB 604

- Dobrynin VD-4K

- Junkers Jumo 222

- Lycoming H-2470

- Pratt & Whitney X-1800

- Pratt & Whitney XH-3130

- Rolls-Royce Eagle

- Wright R-2160 Tornado

Related lists

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Napier-Heston Racer used the first production Sabre engine. The world-record contender crashed during early tests and the project was discontinued.

- ^ 21 Suffolk St, Westminster, London, a little cul-de-sac off Pall Mall East.

- ^ Unlike current "multigrade" motor oils, the lubricants in use in the 1940s thickened up at low temperatures, thus preventing the Sabre from "picking-up" when started.

- ^ List from Lumsden unless otherwise noted.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 ISBN 978-0750917124, p.145

- ^ Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 ISBN 978-0750917124, p.103

- ^ Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford, Douglas Taylor, 1999,ISBN 1 872922 16 3, p.73

- ^ Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 ISBN 978-0750917124, p.186

- ^ Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford, Douglas Taylor, 1999,ISBN 1 872922 16 3, p.81

- ^ Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo, John Reynolds,1999 ISBN 978-0750917124, p.187

- ^ a b c [F C Sheffield] 23 March 1944. "2,200 h.p. Napier Sabre " Flight, p. 309. www.flightglobal.com. Retrieved: 9 November 2009.

- ^ Industry and Air Power The Expansion Of British Aircraft Production 1935-1941, Sebastian Ritchie 2007, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, ISBN 0-7146-4343-2, p.140

- ^ Flight 1945, p.550.

- ^ Aeroplane 2010, pp. 65–66.

- ^ I Kept No Diary-60 Years with Marine Diesels, Automobile and Aero Engines, F.R. Banks 1978, Airlife Publications, ISBN 0 9504543 9 7, p.133

- ^ Napier Sabre Archived 23 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 17 July 2009.

- ^ Sheffield March 1944, p. 310.

- ^ Air Ministry 1943, pp. 24, 25.

- ^ a b c Flight 1945, p. 551.

- ^ Mason 1991, p. 331.

- ^ Flight 1946, p. 91.

- ^ Flight 1945, p. 552.

- ^ Application lists from Lumsden

- ^ CAHC "Workshop One"[usurped] Retrieved: 21 November 2009.

- ^ Lumsden 2003, p.176.

- ^ Flight 1945, pp. 550-553.

Bibliography

[edit]- Air Ministry. Pilot's Notes for Typhoon Marks IA and IB; Sabre II or IIA engine (2nd edition). London: Crecy Publications, 2004. ISBN 0-85979-033-9

- "A Real Contender (article and images) " Aeroplane No. 452, Volume 38, Number 12, December 2010.

- "A Co-operative Challenger (article and images on Heston Racer)." Flight and The Aircraft Engineer No. 1790, Volume XLIII, 15 April 1943.

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines: From the Pioneers to the Present Day. 5th edition, Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4479-X

- Lumsden, Alec. British Piston Engines and Their Aircraft. Marlborough, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-85310-294-6.

- Mason, Francis K. Hawker Aircraft Since 1920 (3rd revised edition). London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-839-9.

- "Napier Sabre VII (article and images)." Flight and The Aircraft Engineer No. 1926, Volume XLVIII, 22 November 1945.

- "Napier Flight Development (article and images on Napier's test and development centre)." Flight and The Aircraft Engineer No. 1961, Volume L, 25 July 1946.

- Setright, L. J. K.: The Power to Fly: The Development of the Piston Engine in Aviation. Allen & Unwin, 1971. ISBN 0-04-338041-7.

- Sheffield, F. C. "2,200 h.p. Napier Sabre (article and images)." Flight and The Aircraft Engineer No. 1829, Volume XLV, 13 January 1944.

- Sheffield, F. C. "Napier Sabre II (article and images)." Flight and The Aircraft Engineer No. 1839, Volume XLV, 23 March 1944.

- White, Graham. Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II: History and Development of Frontline Aircraft Piston Engines Produced by Great Britain and the United States During World War II. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-655-9

- Reynolds, John. Engines and Enterprise: The Life and Work of Sir Harry Ricardo. Stroud, UK: Sutton, 1999. ISBN 978-0750917124

- Taylor, Douglas. Boxkite to Jet - the remarkable career of Frank B Halford. Derby, UK: RRHT, 1999. ISBN 1 872922 16 3

Further reading

[edit]- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1945–1946. London: Samson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd 1946. ISBN 0-517-67964-7 (1989 copy by Crescent Books, NY.)

- Clostermann, Pierre: The Big Show. London, UK: Chatto & Windus in association with William Heinemann, 1953. ISBN 0-297-84619-1 (2004 edition).

External links

[edit]- Napier Power Heritage Trust site

- Cutaway illustration of a Napier Sabre drawn by Max Millar (uncredited) and coloured in by Makoto Oiuchi

- The Sabre-powered Napier-Heston Racer

- The Hawker Tempest Page

- The Greatest Engines of All Time

- NAPIER SABRE 3000 B.H.P A 1946 Flight advertisement for the Sabre engine