Fission-fragment rocket: Difference between revisions

m Spelling/grammar/punctuation/typographical correction |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: journal, title. Add: chapter, doi, authors 1-1. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Whoop whoop pull up | #UCB_webform 3224/3370 |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 17 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description| |

{{short description|Type of nuclear propulsion method with an ultra high specific-inpulse}} |

||

{{ |

{{More citations needed|date=May 2011}} |

||

The '''fission-fragment rocket''' is a [[rocket engine]] design that directly harnesses hot nuclear [[fission product]]s for [[thrust]], as opposed to using a separate fluid as [[working mass]]. The design can, in theory, produce very high [[specific impulse]] while still being well within the abilities of current technologies. |

The '''fission-fragment rocket''' is a [[rocket engine]] design that directly harnesses hot nuclear [[fission product]]s for [[thrust]], as opposed to using a separate fluid as [[working mass]]. The design can, in theory, produce very high [[specific impulse]] while still being well within the abilities of current technologies. |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

== Design considerations == |

== Design considerations == |

||

In traditional [[nuclear thermal rocket]] and related designs, the nuclear energy is generated in some form of [[nuclear reactor|reactor]] and used to heat a working fluid to generate thrust. This limits the designs to temperatures that allow the reactor to remain whole, although clever design can increase this critical temperature into the tens of thousands of degrees. A rocket engine's efficiency is strongly related to the temperature of the exhausted working fluid, and in the case of the most [[Nuclear lightbulb|advanced gas-core engines]], it corresponds to a specific impulse of about 7000 |

In traditional [[nuclear thermal rocket]] and related designs, the nuclear energy is generated in some form of [[nuclear reactor|reactor]] and used to heat a working fluid to generate thrust. This limits the designs to temperatures that allow the reactor to remain whole, although clever design can increase this critical temperature into the tens of thousands of degrees. A rocket engine's efficiency is strongly related to the temperature of the exhausted working fluid, and in the case of the most [[Nuclear lightbulb|advanced gas-core engines]], it corresponds to a [[specific impulse]] of about 7000 s. |

||

The temperature of a conventional reactor design is the average temperature of the fuel, the vast majority of which is not reacting at any given instant. The atoms undergoing fission are at a temperature of millions of degrees, which is then spread out into the surrounding fuel, resulting in an overall temperature of a few thousand. |

The temperature of a conventional reactor design is the average temperature of the fuel, the vast majority of which is not reacting at any given instant. The atoms undergoing fission are at a temperature of millions of degrees, which is then spread out into the surrounding fuel, resulting in an overall temperature of a few thousand. |

||

By physically arranging the fuel into very thin layers or particles, the fragments of a nuclear reaction can escape from the surface. Since they will be [[ionized]] due to the high energy of the reaction, they can then be handled [[magnet]]ically and channeled to produce thrust. Numerous technological challenges still remain, however. |

By physically arranging the fuel into very thin layers or particles, the fragments of a nuclear reaction can escape from the surface. Since they will be [[ionized]] due to the high energy of the reaction, they can then be handled [[magnet]]ically and channeled to produce thrust. Numerous technological challenges still remain, however. |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

== Research == |

== Research == |

||

===Rotating fuel reactor=== |

===Rotating fuel reactor=== |

||

[[Image:Fission fragment propulsion.svg|thumb|right|Fission-fragment propulsion concept |

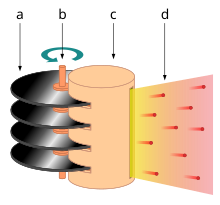

[[Image:Fission fragment propulsion.svg|thumb|right|Fission-fragment propulsion concept{{ordered list|type=lower-alpha|fissionable filaments arranged in disks|revolving shaft|reactor core|fragments exhaust}}]] |

||

A design by the [[Idaho National Engineering Laboratory]] and [[Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]]<ref>Chapline |

A design by the [[Idaho National Engineering Laboratory]] and [[Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]]<ref>{{cite conference |last1= Chapline |first1=G. |last2=Dickson |first2=P. |last3=Schnitzler |first3=B. |url=http://www.osti.gov/bridge/servlets/purl/6868318/6868318.pdf |title=Fission fragment rockets: A potential breakthrough |conference=International reactor physics conference |location=Jackson Hole, Wyoming, USA |date=18 September 1988 |osti=6868318}}</ref> uses fuel placed on the surface of a number of very thin [[carbon]] fibres, arranged radially in wheels. The wheels are normally sub-[[Critical mass (nuclear)|critical]]. Several such wheels were stacked on a common shaft to produce a single large cylinder. The entire cylinder was rotated so that some fibres were always in a reactor core where surrounding moderator made fibres go critical. The fission fragments at the surface of the fibres would break free and be channeled for thrust. The fibre then rotates out of the reaction zone to cool, avoiding melting. |

||

The efficiency of the system is surprising; specific impulses of greater than 100, |

The efficiency of the system is surprising; specific impulses of greater than 100,000 s are possible using existing materials. This is high performance, although the weight of the reactor core and other elements would make the overall performance of the fission-fragment system lower. Nonetheless, the system provides the sort of performance levels that would make an interstellar precursor mission possible. |

||

===Dusty plasma=== |

===Dusty plasma=== |

||

[[Image:Dusty plasma bed reactor.svg|right|thumb|Dusty plasma bed reactor |

[[Image:Dusty plasma bed reactor.svg|right|thumb|Dusty plasma bed reactor{{ubli|style=padding-left:1.7em |

||

|A. fission fragments ejected for propulsion |

|||

|B. reactor |

|||

|C. fission fragments decelerated for power generation |

|||

|d. moderator (BeO or LiH) |

|||

|e. containment field generator |

|||

|f. RF induction coil}}]] |

|||

A newer design proposal by Rodney L. Clark and Robert B. Sheldon theoretically increases efficiency and decreases complexity of a fission fragment rocket at the same time over the rotating fibre wheel proposal.<ref>Clark |

A newer design proposal by Rodney L. Clark and Robert B. Sheldon theoretically increases efficiency and decreases complexity of a fission fragment rocket at the same time over the rotating fibre wheel proposal.<ref>{{cite conference |last1=Clark |first1=R. |last2=Sheldon |first2=R. |url=http://www.rbsp.info/rbs/PDF/aiaa05.pdf |title=Dusty Plasma Based Fission Fragment Nuclear Reactor |publisher=American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics |publication-date=15 April 2007 |conference=41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit |date=10–13 July 2005 |location=Tucson, Arizona |id=AIAA Paper 2005-4460}}</ref> Their design uses [[nanoparticle]]s of fissionable fuel (or even fuel that will naturally radioactively decay) of less than 100 nm diameter. The nanoparticles are kept in a vacuum chamber subject to an [[Axis of rotation|axial]] [[magnetic field]] (acting as a [[magnetic mirror]]) and an external [[electric field]]. As the nanoparticles [[ionization|ionize]] as fission occurs, the dust becomes suspended within the chamber. The incredibly high surface area of the particles makes radiative cooling simple. The axial magnetic field is too weak to affect the motions of the dust particles but strong enough to channel the fragments into a beam which can be decelerated for power, allowed to be emitted for thrust, or a combination of the two. |

||

With exhaust velocities of 3% - 5% the speed of light and efficiencies up to 90%, the rocket should be able to achieve an [[Specific Impulse|''I''<sub>sp</sub>]] of over 1,000,000 seconds. By further injecting the fission fragment exhaust with a neutral gas akin to an [[afterburner]] setup, the resulting heating and interaction can result in a higher, tunable thrust and specific impulse. For realistic designs, some calculations estimate thrusts on the range of 4.5 kN at around 32,000 seconds ''I''<sub>sp</sub>,<ref name="b016">{{cite journal | last1=Gahl | first1=J. | last2=Gillespie | first2=A. K. | last3=Duncan | first3=R. V. | last4=Lin | first4=C. | title=The fission fragment rocket engine for Mars fast transit | journal=Frontiers in Space Technologies | volume=4 | date=2023-10-13 | issn=2673-5075 | doi=10.3389/frspt.2023.1191300 | doi-access=free | page=| arxiv=2308.01441 }}</ref> or even 40 kN at 5,000 seconds ''I''<sub>sp</sub>.<ref name="o735">{{cite conference | last1=Clark | first1=Rodney | last2=Sheldon | first2=Robert | title=41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit | chapter=Dusty Plasma Based Fission Fragment Nuclear Reactor | publisher=American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics | date=2005-07-10 | isbn=978-1-62410-063-5 | doi=10.2514/6.2005-4460 | page=}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In 1987 Ronen & Leibson <ref name=Ronen1987>Ronen |

||

| ⚫ | In 1987, Ronen & Leibson <ref name=Ronen1987>{{cite journal |last1=Ronen |first1=Yigal |first2=Melvin J. |last2=Leibson |title=An example for the potential applications of americium-242m as a nuclear fuel |journal=Transactions – the Israel Nuclear Society |volume=14 |year=1987 |page=V-42}}</ref><ref name=Ronen1988>{{cite journal |last1=Ronen |first1=Yigal |first2=Melvin J. |last2=Leibson |title=Potential applications of 242mAm as a nuclear fuel |journal=Nuclear Science and Engineering |volume=99 |issue=3 |year=1988 |pages= 278–284 |doi=10.13182/NSE88-A28998|bibcode=1988NSE....99..278R }}</ref> published a study on applications of {{sup|242m}}Am (an [[isotope of americium]]) as nuclear fuel to [[Nuclear power in space|space nuclear reactors]], noting its extremely high [[Neutron cross section|thermal cross section]] and [[energy density]]. Nuclear systems powered by {{sup|242m}}Am require less fuel by a factor of 2 to 100 compared to conventional [[nuclear fuel]]s. |

||

| ⚫ | Fission-fragment rocket using |

||

| ⚫ | Fission-fragment rocket using {{sup|242m}}Am was proposed by [[George Chapline Jr.|George Chapline]]<ref name=Chapline1988>{{cite journal | last=Chapline |first = George | title= Fission fragment rocket concept |journal= Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment | volume=271 |issue=1 |year=1988 |pages= 207–208 |doi=10.1016/0168-9002(88)91148-5|bibcode = 1988NIMPA.271..207C }}</ref> at [[Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory]] in 1988, who suggested propulsion based on the direct heating of a propellant gas by fission fragments generated by a fissile material. Ronen et al.<ref name=Ronen/> demonstrate that {{sup|242m}}Am can maintain sustained nuclear fission as an extremely thin metallic film, less than a micrometer thick. {{sup|242m}}Am requires only 1% of the mass of {{sup|235}}U or {{sup|239}}Pu to reach its critical state. Ronen's group at [[Ben-Gurion University of the Negev]] further showed that nuclear fuel based on {{sup|242m}}Am could speed space vehicles from Earth to Mars in as little as two weeks.<ref>{{cite press release |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/01/010103073253.htm |title=Extremely Efficient Nuclear Fuel Could Take Man To Mars In Just Two Weeks |work=Science Daily |date=3 January 2001 |agency=Ben-Gurion University of the Negev}}</ref> |

||

<sup>242m</sup>Am as a nuclear fuel derive from the fact that it has the highest thermal fission cross section (thousands of [[Barn (unit)|barns]]), about 10x the next highest cross section across all known isotopes. |

|||

<sup>242m</sup>Am is [[fissile]] (because it has an odd number of [[neutron]]s) and has a low [[critical mass]], comparable to that of [[plutonium-239|<sup>239</sup>Pu]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Critical Mass Calculations for <sup>241</sup>Am, <sup>242m</sup>Am and <sup>243</sup>Am |url=http://typhoon.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722105207/http://typhoon.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=22 July 2011 |access-date=3 February 2011 }}</ref> <ref>Ludewig, H., et al. "Design of particle bed reactors for the space nuclear thermal propulsion program." Progress in Nuclear Energy 30.1 (1996): 1-65.</ref> |

|||

It has a very high [[Nuclear cross section|cross section]] for fission, and if in a nuclear reactor is destroyed relatively quickly. Another report claims that <sup>242m</sup>Am can sustain a chain reaction even as a thin film, and could be used for a novel type of [[nuclear rocket]].<ref name=Ronen>{{cite journal|last1=Ronen|first1=Yigal|last2=Shwageraus|first2=E.|title=Ultra-thin 241mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors|journal=Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A|date=2000|volume=455|issue=2|pages=442–451|doi=10.1016/s0168-9002(00)00506-4|bibcode=2000NIMPA.455..442R}}</ref><ref name=Ronen2> Ronen, Y., and G. Raitses. "Ultra-thin 242mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors. II." Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment 522.3 (2004): 558-567.</ref><ref name=Ronen2000>Ronen, Yigal, Menashe Aboudy, and Dror Regev. "A Novel Method for Energy Production Using 242 m Am as a Nuclear Fuel." Nuclear technology 129.3 (2000): 407-417.</ref><ref name=Ronen2006> Ronen, Y., E. Fridman, and E. Shwageraus. "The smallest thermal nuclear reactor." Nuclear science and engineering 153.1 (2006): 90-92.</ref> |

|||

{{sup|242m}}Am's potential as a nuclear fuel comes from the fact that it has the highest thermal fission cross section (thousands of [[Barn (unit)|barns]]), about 10x the next highest cross section across all known isotopes. {{sup|242m}}Am is [[fissile]] and has a low [[critical mass]], comparable to [[plutonium-239|{{sup|239}}Pu]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Critical Mass Calculations for {{sup|241}}Am, {{sup|242m}}Am and {{sup|243}}Am |url=http://typhoon.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110722105207/http://typhoon.jaea.go.jp/icnc2003/Proceeding/paper/6.5_022.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=22 July 2011 |access-date=3 February 2011 |first1=Hemanth |last1=Dias |first2=Nigel |last2=Tancock |last3=Angela |first3=Clayton |publisher=Atomic Weapons Establishment plc |location=Aldermaston, Reading, Berkshire}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ludewig |first1=H. |display-authors=etal |title=Design of particle bed reactors for the space nuclear thermal propulsion program |journal=Progress in Nuclear Energy |volume=30 |issue=1 |year=1996 |pages=1–65|doi=10.1016/0149-1970(95)00080-4 }}</ref> It has a very high [[Nuclear cross section|cross section]] for fission, and is destroyed relatively quickly in a nuclear reactor. Another report claims that {{sup|242m}}Am can sustain a chain reaction even as a thin film, and could be used for a novel type of [[nuclear rocket]].<ref name=Ronen>{{cite journal|last1=Ronen|first1=Yigal|last2=Shwageraus|first2=E.|title=Ultra-thin 241mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors|journal=Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A|date=2000|volume=455|issue=2|pages=442–451|doi=10.1016/s0168-9002(00)00506-4|bibcode=2000NIMPA.455..442R}}</ref><ref name=Ronen2>{{cite journal |last1=Ronen |first1=Y. |first2=G. |last2=Raitses |title=Ultra-thin 242mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors. II |journal= Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment |volume=522 |issue=3 |year=2004 |pages=558–567 |doi=10.1016/j.nima.2003.11.421}}</ref><ref name=Ronen2000>{{cite journal |last1=Ronen |first1=Yigal |first2=Menashe |last2=Aboudy |first3=Dror |last3=Regev |title=A Novel Method for Energy Production Using 242 m Am as a Nuclear Fuel |journal=Nuclear Technology |volume=129 |issue=3 |year=2000 |pages=407–417|doi=10.13182/NT00-A3071 }}</ref><ref name=Ronen2006>{{cite journal |last1=Ronen |first1=Y. |first2=E. |last2=Fridman |first3=E. |last3=Shwageraus |title=The smallest thermal nuclear reactor |journal=Nuclear Science and Engineering |volume=153 |issue=1 |year=2006 |pages=90–92|doi=10.13182/NSE06-A2597 }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | Since the thermal [[absorption cross section]] of |

||

| ⚫ | Since the thermal [[absorption cross section]] of {{sup|242m}}Am is very high, the best way to obtain {{sup|242m}}Am is by the capture of [[Neutron temperature#Fast|fast]] or [[Neutron temperature#Epithermal|epithermal]] neutrons in [[Americium-241]] irradiated in a [[Fast-neutron reactor|fast reactor]]. However, [[fast neutron reactor]]s are not readily available. Detailed analysis of {{sup|242m}}Am production in existing [[Pressurized water reactor|PWRs]] was provided in.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Golyand |first1=Leonid |first2=Yigal |last2=Ronen |first3=Eugene |last3=Shwageraus |title=Detailed Design of 242 m Am Breeding in Pressurized Water Reactors |journal=Nuclear Science and Engineering |volume=168 |issue=1 |year=2011 |pages=23–36|doi=10.13182/NSE09-43 }}</ref> [[Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons|Proliferation]] resistance of {{sup|242m}}Am was reported by [[Karlsruhe Institute of Technology]] 2008 study.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kessler |first1=G. |title=Proliferation resistance of americium originating from spent irradiated reactor fuel of pressurized water reactors, fast reactors, and accelerator-driven systems with different fuel cycle options |journal=Nuclear Science and Engineering |volume=159 |issue=1 |year=2008 |pages=56–82|doi=10.13182/NSE159-56 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In 2000 [[Carlo Rubbia]] at [[CERN]] further extended the work by Ronen |

||

| ⚫ | In 2000, [[Carlo Rubbia]] at [[CERN]] further extended the work by Ronen<ref name=Ronen1988/> and [[George Chapline Jr.|Chapline]]<ref name=Chapline1988 /> on fission-fragment rocket using {{sup|242m}}Am as a fuel.<ref name=Rubbia2000>{{cite report |last=Rubbia |first=Carlo |title=Fission fragments heating for space propulsion |id=No. SL-Note-2000-036-EET. CERN-SL-Note-2000-036-EET |year=2000}}</ref> Project 242<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Augelli |first1=M. |first2=G. F. |last2=Bignami |first3=G. |last3=Genta |title=Project 242: Fission fragments direct heating for space propulsion—Programme synthesis and applications to space exploration |journal=Acta Astronautica |volume=82 |issue=2 |year=2013 |pages=153–158|doi=10.1016/j.actaastro.2012.04.007 }}</ref> based on Rubbia design studied a concept of {{sup|242m}}Am based Thin-Film Fission Fragment Heated [[Nuclear thermal rocket|NTR]]<ref>{{cite report |last=Davis |first=Eric W. |title=Advanced propulsion study |publisher=Warp Drive Metrics |year=2004 |url=https://inspirehep.net/literature/1848385}}</ref> by using direct conversion of the kinetic energy of fission fragments into increasing of enthalpy of a propellant gas. Project 242 studied the application of this propulsion system to a crewed mission to Mars.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Cesana |first=Alessandra |display-authors=etal |title=Some Considerations on 242 m Am Production in Thermal Reactors |journal=Nuclear Technology |volume=148 |issue=1 |year=2004 |pages=97–101|doi=10.13182/NT04-A3550 }}</ref> Preliminary results were very satisfactory and it has been observed that a propulsion system with these characteristics could make the mission feasible. Another study focused on production of {{sup|242m}}Am in conventional thermal nuclear reactors.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Benetti |first=P. |display-authors=etal |title=Production of 242mAm |journal=Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment |volume=564 |issue=1 |year=2006 |pages=48–485|doi=10.1016/j.nima.2006.04.029 }}</ref> |

||

=== Aerogel core === |

|||

On 9 January 2023, NASA announced funding the study of an "Aerogel Core Fission Fragment Rocket Engine", where fissile fuel particles will be embedded in an ultra-low density [[aerogel]] matrix to achieve a critical mass assembly. The aerogel matrix (and a strong magnetic field) would allow fission fragments to escape the core, while increasing conductive and radiative heat loss from the individual fuel particles.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/directorates/spacetech/niac/2023/Aerogel_Core_Fission_Fragment_Rocket_Engine |title=Aerogel Core Fission Fragment Rocket Engine <!--Unclear who actually wrote this article as there are two names, with no roles labelled. Just citing both as authors -->|first1=Loura |last1=Hall |date=9 January 2023 |first2=Ryan |last2=Weed |publisher=NASA |access-date=21 July 2024}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[Fission |

* [[Fission sail]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Nuclear salt-water rocket]] |

* [[Nuclear salt-water rocket]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Fission fragment reactor]] |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

| Line 54: | Line 60: | ||

{{Nuclear propulsion}} |

{{Nuclear propulsion}} |

||

[[Category:Americium]] |

|||

[[Category:Nuclear spacecraft propulsion]] |

[[Category:Nuclear spacecraft propulsion]] |

||

Latest revision as of 09:32, 29 September 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

The fission-fragment rocket is a rocket engine design that directly harnesses hot nuclear fission products for thrust, as opposed to using a separate fluid as working mass. The design can, in theory, produce very high specific impulse while still being well within the abilities of current technologies.

Design considerations

[edit]In traditional nuclear thermal rocket and related designs, the nuclear energy is generated in some form of reactor and used to heat a working fluid to generate thrust. This limits the designs to temperatures that allow the reactor to remain whole, although clever design can increase this critical temperature into the tens of thousands of degrees. A rocket engine's efficiency is strongly related to the temperature of the exhausted working fluid, and in the case of the most advanced gas-core engines, it corresponds to a specific impulse of about 7000 s.

The temperature of a conventional reactor design is the average temperature of the fuel, the vast majority of which is not reacting at any given instant. The atoms undergoing fission are at a temperature of millions of degrees, which is then spread out into the surrounding fuel, resulting in an overall temperature of a few thousand.

By physically arranging the fuel into very thin layers or particles, the fragments of a nuclear reaction can escape from the surface. Since they will be ionized due to the high energy of the reaction, they can then be handled magnetically and channeled to produce thrust. Numerous technological challenges still remain, however.

Research

[edit]Rotating fuel reactor

[edit]

- fissionable filaments arranged in disks

- revolving shaft

- reactor core

- fragments exhaust

A design by the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory[1] uses fuel placed on the surface of a number of very thin carbon fibres, arranged radially in wheels. The wheels are normally sub-critical. Several such wheels were stacked on a common shaft to produce a single large cylinder. The entire cylinder was rotated so that some fibres were always in a reactor core where surrounding moderator made fibres go critical. The fission fragments at the surface of the fibres would break free and be channeled for thrust. The fibre then rotates out of the reaction zone to cool, avoiding melting.

The efficiency of the system is surprising; specific impulses of greater than 100,000 s are possible using existing materials. This is high performance, although the weight of the reactor core and other elements would make the overall performance of the fission-fragment system lower. Nonetheless, the system provides the sort of performance levels that would make an interstellar precursor mission possible.

Dusty plasma

[edit]

- A. fission fragments ejected for propulsion

- B. reactor

- C. fission fragments decelerated for power generation

- d. moderator (BeO or LiH)

- e. containment field generator

- f. RF induction coil

A newer design proposal by Rodney L. Clark and Robert B. Sheldon theoretically increases efficiency and decreases complexity of a fission fragment rocket at the same time over the rotating fibre wheel proposal.[2] Their design uses nanoparticles of fissionable fuel (or even fuel that will naturally radioactively decay) of less than 100 nm diameter. The nanoparticles are kept in a vacuum chamber subject to an axial magnetic field (acting as a magnetic mirror) and an external electric field. As the nanoparticles ionize as fission occurs, the dust becomes suspended within the chamber. The incredibly high surface area of the particles makes radiative cooling simple. The axial magnetic field is too weak to affect the motions of the dust particles but strong enough to channel the fragments into a beam which can be decelerated for power, allowed to be emitted for thrust, or a combination of the two.

With exhaust velocities of 3% - 5% the speed of light and efficiencies up to 90%, the rocket should be able to achieve an Isp of over 1,000,000 seconds. By further injecting the fission fragment exhaust with a neutral gas akin to an afterburner setup, the resulting heating and interaction can result in a higher, tunable thrust and specific impulse. For realistic designs, some calculations estimate thrusts on the range of 4.5 kN at around 32,000 seconds Isp,[3] or even 40 kN at 5,000 seconds Isp.[4]

Am-242m as nuclear fuel

[edit]In 1987, Ronen & Leibson [5][6] published a study on applications of 242mAm (an isotope of americium) as nuclear fuel to space nuclear reactors, noting its extremely high thermal cross section and energy density. Nuclear systems powered by 242mAm require less fuel by a factor of 2 to 100 compared to conventional nuclear fuels.

Fission-fragment rocket using 242mAm was proposed by George Chapline[7] at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 1988, who suggested propulsion based on the direct heating of a propellant gas by fission fragments generated by a fissile material. Ronen et al.[8] demonstrate that 242mAm can maintain sustained nuclear fission as an extremely thin metallic film, less than a micrometer thick. 242mAm requires only 1% of the mass of 235U or 239Pu to reach its critical state. Ronen's group at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev further showed that nuclear fuel based on 242mAm could speed space vehicles from Earth to Mars in as little as two weeks.[9]

242mAm's potential as a nuclear fuel comes from the fact that it has the highest thermal fission cross section (thousands of barns), about 10x the next highest cross section across all known isotopes. 242mAm is fissile and has a low critical mass, comparable to 239Pu.[10][11] It has a very high cross section for fission, and is destroyed relatively quickly in a nuclear reactor. Another report claims that 242mAm can sustain a chain reaction even as a thin film, and could be used for a novel type of nuclear rocket.[8][12][13][14]

Since the thermal absorption cross section of 242mAm is very high, the best way to obtain 242mAm is by the capture of fast or epithermal neutrons in Americium-241 irradiated in a fast reactor. However, fast neutron reactors are not readily available. Detailed analysis of 242mAm production in existing PWRs was provided in.[15] Proliferation resistance of 242mAm was reported by Karlsruhe Institute of Technology 2008 study.[16]

In 2000, Carlo Rubbia at CERN further extended the work by Ronen[6] and Chapline[7] on fission-fragment rocket using 242mAm as a fuel.[17] Project 242[18] based on Rubbia design studied a concept of 242mAm based Thin-Film Fission Fragment Heated NTR[19] by using direct conversion of the kinetic energy of fission fragments into increasing of enthalpy of a propellant gas. Project 242 studied the application of this propulsion system to a crewed mission to Mars.[20] Preliminary results were very satisfactory and it has been observed that a propulsion system with these characteristics could make the mission feasible. Another study focused on production of 242mAm in conventional thermal nuclear reactors.[21]

Aerogel core

[edit]On 9 January 2023, NASA announced funding the study of an "Aerogel Core Fission Fragment Rocket Engine", where fissile fuel particles will be embedded in an ultra-low density aerogel matrix to achieve a critical mass assembly. The aerogel matrix (and a strong magnetic field) would allow fission fragments to escape the core, while increasing conductive and radiative heat loss from the individual fuel particles.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chapline, G.; Dickson, P.; Schnitzler, B. (18 September 1988). Fission fragment rockets: A potential breakthrough (PDF). International reactor physics conference. Jackson Hole, Wyoming, USA. OSTI 6868318.

- ^ Clark, R.; Sheldon, R. (10–13 July 2005). Dusty Plasma Based Fission Fragment Nuclear Reactor (PDF). 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit. Tucson, Arizona: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (published 15 April 2007). AIAA Paper 2005-4460.

- ^ Gahl, J.; Gillespie, A. K.; Duncan, R. V.; Lin, C. (2023-10-13). "The fission fragment rocket engine for Mars fast transit". Frontiers in Space Technologies. 4. arXiv:2308.01441. doi:10.3389/frspt.2023.1191300. ISSN 2673-5075.

- ^ Clark, Rodney; Sheldon, Robert (2005-07-10). "Dusty Plasma Based Fission Fragment Nuclear Reactor". 41st AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2005-4460. ISBN 978-1-62410-063-5.

- ^ Ronen, Yigal; Leibson, Melvin J. (1987). "An example for the potential applications of americium-242m as a nuclear fuel". Transactions – the Israel Nuclear Society. 14: V-42.

- ^ a b Ronen, Yigal; Leibson, Melvin J. (1988). "Potential applications of 242mAm as a nuclear fuel". Nuclear Science and Engineering. 99 (3): 278–284. Bibcode:1988NSE....99..278R. doi:10.13182/NSE88-A28998.

- ^ a b Chapline, George (1988). "Fission fragment rocket concept". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 271 (1): 207–208. Bibcode:1988NIMPA.271..207C. doi:10.1016/0168-9002(88)91148-5.

- ^ a b Ronen, Yigal; Shwageraus, E. (2000). "Ultra-thin 241mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research A. 455 (2): 442–451. Bibcode:2000NIMPA.455..442R. doi:10.1016/s0168-9002(00)00506-4.

- ^ "Extremely Efficient Nuclear Fuel Could Take Man To Mars In Just Two Weeks". Science Daily (Press release). Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. 3 January 2001.

- ^ Dias, Hemanth; Tancock, Nigel; Angela, Clayton. "Critical Mass Calculations for 241Am, 242mAm and 243Am" (PDF). Aldermaston, Reading, Berkshire: Atomic Weapons Establishment plc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ Ludewig, H.; et al. (1996). "Design of particle bed reactors for the space nuclear thermal propulsion program". Progress in Nuclear Energy. 30 (1): 1–65. doi:10.1016/0149-1970(95)00080-4.

- ^ Ronen, Y.; Raitses, G. (2004). "Ultra-thin 242mAm fuel elements in nuclear reactors. II". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 522 (3): 558–567. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2003.11.421.

- ^ Ronen, Yigal; Aboudy, Menashe; Regev, Dror (2000). "A Novel Method for Energy Production Using 242 m Am as a Nuclear Fuel". Nuclear Technology. 129 (3): 407–417. doi:10.13182/NT00-A3071.

- ^ Ronen, Y.; Fridman, E.; Shwageraus, E. (2006). "The smallest thermal nuclear reactor". Nuclear Science and Engineering. 153 (1): 90–92. doi:10.13182/NSE06-A2597.

- ^ Golyand, Leonid; Ronen, Yigal; Shwageraus, Eugene (2011). "Detailed Design of 242 m Am Breeding in Pressurized Water Reactors". Nuclear Science and Engineering. 168 (1): 23–36. doi:10.13182/NSE09-43.

- ^ Kessler, G. (2008). "Proliferation resistance of americium originating from spent irradiated reactor fuel of pressurized water reactors, fast reactors, and accelerator-driven systems with different fuel cycle options". Nuclear Science and Engineering. 159 (1): 56–82. doi:10.13182/NSE159-56.

- ^ Rubbia, Carlo (2000). Fission fragments heating for space propulsion (Report). No. SL-Note-2000-036-EET. CERN-SL-Note-2000-036-EET.

- ^ Augelli, M.; Bignami, G. F.; Genta, G. (2013). "Project 242: Fission fragments direct heating for space propulsion—Programme synthesis and applications to space exploration". Acta Astronautica. 82 (2): 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2012.04.007.

- ^ Davis, Eric W. (2004). Advanced propulsion study (Report). Warp Drive Metrics.

- ^ Cesana, Alessandra; et al. (2004). "Some Considerations on 242 m Am Production in Thermal Reactors". Nuclear Technology. 148 (1): 97–101. doi:10.13182/NT04-A3550.

- ^ Benetti, P.; et al. (2006). "Production of 242mAm". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment. 564 (1): 48–485. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2006.04.029.

- ^ Hall, Loura; Weed, Ryan (9 January 2023). "Aerogel Core Fission Fragment Rocket Engine". NASA. Retrieved 21 July 2024.