The Iron Man (novel): Difference between revisions

→top: wasn't Poet Laureate at the time, not for another 16 years |

|||

| (46 intermediate revisions by 36 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|1968 novel by Ted Hughes}} |

||

{{ |

{{For|novels with similar titles|Ironman (disambiguation)#Literature}} |

||

{{EngvarB|date=September 2017}} |

{{EngvarB|date=September 2017}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2018}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2018}} |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''The Iron Man: A Children's Story in Five Nights''''' is a 1968 science fiction novel by [[ |

'''''The Iron Man: A Children's Story in Five Nights''''' is a 1968 science fiction novel by [[Ted Hughes]], future [[British Poet Laureate]], first published by [[Faber and Faber]] in the UK with illustrations by [[George Worsley Adamson|George Adamson]].<ref>The subtitle of the first edition was ''A Story in Five Nights''. See also [http://www.georgewadamson.com/ironman.html ''The Iron Man'' page] on the official [http://www.georgewadamson.com George Adamson web site].</ref> Described by some as a modern fairy tale,<ref name=walker>{{Cite web| title = The Iron Man| publisher = Presentation of the 2010 edition by publisher [[Walker Books]]| url = http://www.walker.co.uk/The-Iron-Man-9781406324679.aspx| accessdate = 7 December 2010| url-status = dead| archiveurl = https://web.archive.org/web/20110216011452/http://www.walker.co.uk/The-Iron-Man-9781406324679.aspx| archivedate = 16 February 2011| df = dmy-all}} Quote: "Reckoned one of the greatest of modern fairy tales." ''Observer''.</ref> it narrates the unexpected arrival in England of a giant "metal man" of unknown origin who rains destruction on the countryside by eating [[agricultural equipment|industrial farm equipment]], before befriending a small boy and defending the world from a dragon from outer space. Expanding the narrative beyond a criticism of warfare and inter-human conflict, Hughes later wrote a sequel, ''[[The Iron Woman]]'' (1993), describing retribution based on [[environmentalism|environmental themes]] related to pollution. |

||

</ref> it describes the unexpected arrival in England of a giant "metal man" of unknown origin who rains destruction on the countryside by eating [[agricultural equipment|industrial farm equipment]], before befriending a small boy and defending the world from a dragon from outer space. Expanding the narrative beyond a criticism of warfare and inter-human conflict, Hughes later wrote a sequel, ''[[The Iron Woman]]'' (1993), describing retribution based on [[environmentalism|environmental themes]] related to pollution. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The first North American edition was also published in 1968, by [[Harper & Row]] with illustrations by Robert Nadler.<!--source is LCCat--> Its main title was changed to '''''The Iron Giant''''', and internal mentions of the metal man changed to iron giant, to avoid confusion with the [[Marvel Comics]] character [[Iron Man]]. American editions have continued the practice, as Iron Man has become a multimedia franchise. |

||

The Iron Man arrives seemingly from nowhere, and his appearance is described in detail. He first appears falling off a cliff, but his various pieces reassemble themselves, starting with his hands finding his eyes and progressing from there. He is unable to find one ear, which was taken by seagulls earlier, and walks into the sea to find it. |

|||

| ⚫ | He eventually returns to the country and begins to feed on local farm equipment. When the farm hands discover their destroyed tractors and diggers, a trap is set consisting of a covered pit on which a red lorry is set as bait. Hogarth, a local boy, lures the Iron Man to the trap. The plan succeeds, and the Iron Man is buried alive. The next spring, the Iron Man digs himself free of the pit. To keep him out of the way, Hogarth brings the Iron Man to a scrap-heap to feast. The Iron Man promises not to cause further trouble for the locals, as long as no one troubles him. |

||

| ⚫ | Faber and Faber published a new edition in 1985 with illustrations by [[Andrew Davidson (illustrator)|Andrew Davidson]], for which Hughes and Davidson won the [[Kurt Maschler Award]], or the Emils. From 1982 to 1999 that award recognised one British "work of imagination for children, in which text and illustration are integrated so that each enhances and balances the other."<ref name=bizland/><ref name=isfdb/> The 1985 Davidson edition was published in Britain and America (retaining 'giant') and there were re-issues with the Davidson illustrations, including some with other cover artists.<!--ISFDB--> Yet the novel has been re-illustrated by at least two others, Dirk Zimmer and Laura Carlin (current, Walker Books).<ref name=walker/><!--LC online catalogue has five editions with those five illustrators, perhaps first printings for the two 1968 only. See TALK#Editions--> |

||

| ⚫ | Time passes, and the Iron Man is treated as merely another member of the community. However, astronomers monitoring the sky make a frightening new discovery: an enormous space-being, resembling a dragon, moving from orbit to land on Earth. The creature (soon dubbed the "Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon") crashes heavily on Australia (which it is large enough to cover the whole of) and demands that humanity provide him with food (anything alive) or he will take it by force. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Terrified, humans send their armies to destroy the dragon, but it is unharmed by their weapons. When the Iron Man hears of this global threat, he allows himself to be disassembled and transported to Australia where he challenges the creature to a contest of strength. If the Iron Man can withstand the heat of burning petroleum for longer than the creature can withstand the heat of the Sun, the creature must obey the Iron Man's commands forevermore: if the Iron Man melts or is afraid of melting before the space being undergoes or fears pain in the Sun, the creature has permission to devour the whole Earth. |

||

| ⚫ | Time passes, and the Iron Man is treated as merely another member of the community. However, astronomers monitoring the sky make a frightening new discovery |

||

| ⚫ | After playing this game for two rounds, the dragon is so badly burned that he no longer appears physically frightening. The Iron Man by contrast has only a deformed ear-lobe to show for his pains. The alien creature admits defeat. When asked why he came to Earth, the dragon reveals that he is a peaceful "star spirit" who experienced excitement about the ongoing sights and sounds produced by the violent warfare of humanity. In his own life, he was a singer of the "[[Musica universalis|music of the spheres]]"; the harmony of his kind that keeps the [[cosmos]] in [[Balance (metaphysics)|balance]] in stable equilibrium. |

||

| ⚫ | Terrified, humans send their armies to destroy the dragon, but it |

||

| ⚫ | After playing |

||

The Iron Man orders the dragon to sing to the inhabitants of Earth, flying just behind the sunset, to help soothe humanity toward a sense of peace. The beauty of his music distracts the population from its egocentrism and tendency to fight, causing the first worldwide lasting peace. |

The Iron Man orders the dragon to sing to the inhabitants of Earth, flying just behind the sunset, to help soothe humanity toward a sense of peace. The beauty of his music distracts the population from its egocentrism and tendency to fight, causing the first worldwide lasting peace. |

||

== |

== Publishing == |

||

| ⚫ | The first North American edition was also published in 1968, by [[Harper & Row]] with illustrations by Robert Nadler.<!--source is LCCat--> Its main title was changed to '''''The Iron Giant''''', and internal mentions of the metal man changed to iron giant, to avoid confusion with the [[Marvel Comics]] character [[Iron Man]]. American editions have continued the practice, as Iron Man has become a multimedia franchise. |

||

The story was featured several times on the BBC's'' [[Jackanory]]'', most recently in 1985 when it was read by Tom Baker. |

|||

| ⚫ | Faber and Faber published a new edition in 1985 with illustrations by [[Andrew Davidson (illustrator)|Andrew Davidson]], for which Hughes and Davidson won the [[Kurt Maschler Award]], or the Emils. From 1982 to 1999 that award recognised one British "work of imagination for children, in which text and illustration are integrated so that each enhances and balances the other."<ref name=bizland/><ref name=isfdb/> The 1985 Davidson edition was published in Britain and America (retaining 'giant') and there were re-issues with the Davidson illustrations, including some with other cover artists.<!--ISFDB--> Yet the novel has been re-illustrated by at least two others, Dirk Zimmer and Laura Carlin (current, Walker Books).<ref name=walker/><!--LC online catalogue has five editions with those five illustrators, perhaps first printings for the two 1968 only. See TALK#Editions--> |

||

In 1989, guitarist [[Pete Townshend]], from the rock band [[The Who]], released a [[rock opera]] adaptation, ''[[The Iron Man: The Musical by Pete Townshend|The Iron Man: A Musical]]''. |

|||

In August 2019, an updated illustrated version was released in the UK with new illustrations from artist Chris Mould.<!--LC Cat--> |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1999, [[Warner |

||

<!-- |

|||

== |

==Adaptations== |

||

*[[Pete Townshend]] produced a [[The Iron Man: The Musical by Pete Townshend|musical concept album]] based on the novel in 1989. |

|||

don't repeat basic links such as our sequel article |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

--> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist |25em |refs= |

{{Reflist |25em |refs= |

||

| ⚫ | |||

<ref name=isfdb> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

<ref name=bizland> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 90: | Line 84: | ||

* [http://www.primaryresources.co.uk/english/iron.htm The Iron Man by Ted Hughes] at Primary Resources |

* [http://www.primaryresources.co.uk/english/iron.htm The Iron Man by Ted Hughes] at Primary Resources |

||

{{Ted Hughes}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 98: | Line 93: | ||

[[Category:Children's science fiction novels]] |

[[Category:Children's science fiction novels]] |

||

[[Category:Novels by Ted Hughes]] |

[[Category:Novels by Ted Hughes]] |

||

[[Category:Faber |

[[Category:Faber & Faber books]] |

||

[[Category:British novels adapted into plays]] |

[[Category:British novels adapted into plays]] |

||

[[Category:British novels adapted into films]] |

[[Category:British novels adapted into films]] |

||

[[Category:1968 children's books]] |

[[Category:1968 children's books]] |

||

[[Category:Fiction about giants]] |

|||

[[Category:Fictional humanoid robots]] |

[[Category:Fictional humanoid robots]] |

||

[[Category:Science fiction novels adapted into films]] |

[[Category:Science fiction novels adapted into films]] |

||

Latest revision as of 12:42, 16 October 2024

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

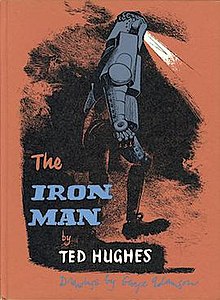

Adamson cover of first edition | |

| Author | Ted Hughes |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | George Adamson (first) Andrew Davidson (1985) |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Published | 1968 (Faber and Faber, UK) 1968 (Harper & Row, US) 1985 (Faber and Faber, int'l) 1999 (Knopf, 30th Anniv. Ed.) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 59 pp. |

| Followed by | The Iron Woman |

The Iron Man: A Children's Story in Five Nights is a 1968 science fiction novel by Ted Hughes, future British Poet Laureate, first published by Faber and Faber in the UK with illustrations by George Adamson.[1] Described by some as a modern fairy tale,[2] it narrates the unexpected arrival in England of a giant "metal man" of unknown origin who rains destruction on the countryside by eating industrial farm equipment, before befriending a small boy and defending the world from a dragon from outer space. Expanding the narrative beyond a criticism of warfare and inter-human conflict, Hughes later wrote a sequel, The Iron Woman (1993), describing retribution based on environmental themes related to pollution.

Story

[edit]The Iron Man arrives seemingly from nowhere, and his appearance is described in detail. He first appears falling off a cliff, but his various pieces reassemble themselves, starting with his hands finding his eyes and progressing from there. He is unable to find one ear, which was taken by seagulls earlier, and walks into the sea to find it.

He eventually returns to the country and begins to feed on local farm equipment. When the farm hands discover their destroyed tractors and diggers, a trap is set consisting of a covered pit on which a red lorry is set as bait. Hogarth, a local boy, lures the Iron Man to the trap. The plan succeeds, and the Iron Man is buried alive. The next spring, the Iron Man digs himself free of the pit. To keep him out of the way, Hogarth brings the Iron Man to a scrap-heap to feast. The Iron Man promises not to cause further trouble for the locals, as long as no one troubles him.

Time passes, and the Iron Man is treated as merely another member of the community. However, astronomers monitoring the sky make a frightening new discovery: an enormous space-being, resembling a dragon, moving from orbit to land on Earth. The creature (soon dubbed the "Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon") crashes heavily on Australia (which it is large enough to cover the whole of) and demands that humanity provide him with food (anything alive) or he will take it by force.

Terrified, humans send their armies to destroy the dragon, but it is unharmed by their weapons. When the Iron Man hears of this global threat, he allows himself to be disassembled and transported to Australia where he challenges the creature to a contest of strength. If the Iron Man can withstand the heat of burning petroleum for longer than the creature can withstand the heat of the Sun, the creature must obey the Iron Man's commands forevermore: if the Iron Man melts or is afraid of melting before the space being undergoes or fears pain in the Sun, the creature has permission to devour the whole Earth.

After playing this game for two rounds, the dragon is so badly burned that he no longer appears physically frightening. The Iron Man by contrast has only a deformed ear-lobe to show for his pains. The alien creature admits defeat. When asked why he came to Earth, the dragon reveals that he is a peaceful "star spirit" who experienced excitement about the ongoing sights and sounds produced by the violent warfare of humanity. In his own life, he was a singer of the "music of the spheres"; the harmony of his kind that keeps the cosmos in balance in stable equilibrium.

The Iron Man orders the dragon to sing to the inhabitants of Earth, flying just behind the sunset, to help soothe humanity toward a sense of peace. The beauty of his music distracts the population from its egocentrism and tendency to fight, causing the first worldwide lasting peace.

Publishing

[edit]The first North American edition was also published in 1968, by Harper & Row with illustrations by Robert Nadler. Its main title was changed to The Iron Giant, and internal mentions of the metal man changed to iron giant, to avoid confusion with the Marvel Comics character Iron Man. American editions have continued the practice, as Iron Man has become a multimedia franchise.

Faber and Faber published a new edition in 1985 with illustrations by Andrew Davidson, for which Hughes and Davidson won the Kurt Maschler Award, or the Emils. From 1982 to 1999 that award recognised one British "work of imagination for children, in which text and illustration are integrated so that each enhances and balances the other."[3][4] The 1985 Davidson edition was published in Britain and America (retaining 'giant') and there were re-issues with the Davidson illustrations, including some with other cover artists. Yet the novel has been re-illustrated by at least two others, Dirk Zimmer and Laura Carlin (current, Walker Books).[2]

In August 2019, an updated illustrated version was released in the UK with new illustrations from artist Chris Mould.

Adaptations

[edit]- Pete Townshend produced a musical concept album based on the novel in 1989.

- In 1999, Warner Bros. released an animated film using the novel as a basis, titled The Iron Giant, directed by Brad Bird and co-produced by Pete Townshend.

References

[edit]- ^ The subtitle of the first edition was A Story in Five Nights. See also The Iron Man page on the official George Adamson web site.

- ^ a b "The Iron Man". Presentation of the 2010 edition by publisher Walker Books. Archived from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010. Quote: "Reckoned one of the greatest of modern fairy tales." Observer.

- ^ "Kurt Maschler Awards". Book Awards. bizland.com. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ The Iron Man: A Story in Five Nights title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved 6 October 2013. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image (7 available) or linked contents. For the 1968 and 1985 editions, later printings only.

Bibliography

[edit]- The Iron Man, illus. by George Adamson. London: Faber and Faber, 26 February 1968 ISBN 0571 08247 5

- The Iron Giant, illus. by Robert Nadler. New York: Harper & Row, 23 October 1968

- The Iron Man, illus. by George Adamson. London: Faber and Faber, 11 October 1971 (paperback edition) ISBN 0571 09750 2

- L'Uomo di Ferro: Lotta di giganti per la salvezza della terra, transl. into Italian of The Iron Man by Sandra Georgini, illus. by George Adamson. Milan: Biblioteca Universale, Rizzoli, 1977

- The Iron Man, illus. by George Adamson: “English language textbook with Japanese annotations” by Yuuichi Hashimoto. Tokyo: Shinozaki Shorin, 1980

- A Vasember, transl. into Hungarian of The Iron Man by Katalin Damokos, illus. György Korga . Budapest: Móra Könyvkiadó, 1981 ISBN 978-963-11-2373-9

- Le Géant de fer, transl. into French of The Iron Man by Sophie de Vogelas; illus. by Philippe Munch; Folio cadet 52. Éditions Gallimard Jeunesse, 1984 ISBN 978-2-07-031052-4

- The Iron Man, illus. by Andrew Davidson. London: Faber and Faber, 1985 ISBN 978-0-571-13675-9 (cased); ISBN 978-0-571-13677-3 (paperback)

- The Iron Giant, illus. by Dirk Zimmer. New York: Harper & Row, 1988 ISBN 978-0-06-022638-1

- The Iron Man, illus. by Andrew Davidson. London: Faber and Faber, 1989 ISBN 978-0-571-14149-4 (paperback)

- Le Géant de fer, transl. into French of The Iron Man by Sophie de Vogelas; illus. by Jean Torton; Folio cadet 295. Éditions Gallimard Jeunesse, 1992 ISBN 978-2-07-052686-4

- Rautamies, transl. into Finnish of The Iron Man by Sinikka Sajama; illus. Andrew Davidson. Karkkila: Kustannus-Mäkelä, 1993 ISBN 978-951-873-267-2

- Der Eisenmann, transl. into German of The Iron Man by U.-M. Gutzschhahn, illus. by Jindra Čapek. Frankfurt-am-Main: S. Fischer (Fischer Taschenbuch) 1997 ISBN 3-596-80154-0

- The Iron Giant, illus. by Andrew Davidson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999 ISBN 978-0-375-80167-9; (reprinted as a paperback by Yearling Books, an imprint of Random House ISBN 978-0-375-80153-2)

- L'Uomo di ferro, transl. into Italian of The Iron Man by Ilva Tron; illus. by Andrew Davidson; Junior Mondadori series. Milan: Mondadori, 2003 ISBN 88-04-43681-6

- Y dyn haearn, transl. into Welsh of The Iron Man by Emily Huws; illus. by Andrew Davidson. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2004 ISBN 978-0-86381-936-0

- The Iron Man, illus. by Tom Gauld. London: Faber and Faber, 2005 ISBN 978-0-571-22612-2

- The Iron Man, illus. by Laura Carlin. London: Walker Books in collaboration with Faber and Faber, 2010 ISBN 978-1-4063-2957-5

- El hombre de hierro, illus. by Laura Carlin. Barcelona: Vicens Vives, 2011 ISBN 9788468206219 OCLC 794039831

- The Iron Man, illus. by Andrew Davidson. London: Faber and Faber, 2013 ISBN 978-0-571-30224-6 (paperback)

- L'Uomo di ferro, transl. into Italian of The Iron Man by Ilva Tron, illus. by I. Bruno. Milan: Oscar junior, Mondadori, 2013 ISBN 978-88-04-62032-7

External links

[edit]- The Iron Man by Ted Hughes at Primary Resources

- 1968 British novels

- 1968 science fiction novels

- British children's novels

- Children's science fiction novels

- Novels by Ted Hughes

- Faber & Faber books

- British novels adapted into plays

- British novels adapted into films

- 1968 children's books

- Fiction about giants

- Fictional humanoid robots

- Science fiction novels adapted into films