Guercino: Difference between revisions

Rococo1700 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 19 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|17th-century painter of the Italian Seicento}} |

||

{{Infobox artist |

{{Infobox artist |

||

| name = Guercino |

| name = Guercino |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

| image_size = |

| image_size = |

||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

| caption = Self portrait, c. |

| caption = Self portrait, {{c.|1635}} |

||

| birth_name = Giovanni Francesco Barbieri |

| birth_name = Giovanni Francesco Barbieri |

||

| birth_date = {{birth date |1591|02|08 |

| birth_date = {{birth date |1591|02|08}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Cento]] |

| birth_place = [[Cento]], [[Duchy of Ferrara]] |

||

| death_date = {{death date and age |1666|12|22|1591|02|08 |

| death_date = {{death date and age |1666|12|22|1591|02|08}} |

||

| death_place = [[Bologna]] |

| death_place = [[Bologna]], [[Papal States]] |

||

| nationality = [[ |

| nationality = [[Italians|Italian]] |

||

| known_for = [[Painting]], [[drawing]] |

| known_for = [[Painting]], [[drawing]] |

||

| training = |

| training = |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Giovanni Francesco Barbieri''' (February 8, 1591 – December 22, 1666),<ref name=TreccaniBiografico1964>Miller, 1964</ref> better known as '''Guercino''' |

'''Giovanni Francesco Barbieri''' (February 8, 1591 – December 22, 1666),<ref name="TreccaniBiografico1964">Miller, 1964</ref> better known as ('''il''') '''Guercino'''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://besidetheeasel.blogspot.se/2013/02/guercino-il-magnifico.html|title=Beside the easel |publisher=besidetheeasel.blogspot.se|access-date=14 September 2017}}</ref> ({{IPA|it|ɡwerˈtʃiːno|-|It-Guercino.wav}}), was an [[Italian Baroque painter]] and draftsman from [[Cento]] in the [[Emilia-Romagna|Emilia]] region, who was active in [[Rome]] and [[Bologna]]. The vigorous naturalism of his early manner contrasts with the classical equilibrium of his later works. His many drawings are noted for their luminosity and lively style. |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

[[File:Et-in-Arcadia-ego.jpg|thumb|left|The dramatic confrontation with mortality depicted in Guercino's [[Et in Arcadia ego (Guercino)|''Et in Arcadia ego'']] (c. |

[[File:Et-in-Arcadia-ego.jpg|thumb|left|The dramatic confrontation with mortality depicted in Guercino's [[Et in Arcadia ego (Guercino)|''Et in Arcadia ego'']] (c. 1618–1622) marks the first known usage of this Latin motto (inscribed on the plinth beneath the skull). ]] |

||

[[File:Francesco_Barbieri.jpg|thumb| This contemporary portrait (1623) by [[Ottavio Leoni]]<ref>{{cite web |title=Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino |

[[File:Francesco_Barbieri.jpg|thumb| This contemporary portrait (1623) by [[Ottavio Leoni]]<ref>{{cite web |title=Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino – Ottavio Leoni |url=http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/explore/collection/work/22613/ |website=www.ngv.vic.gov.au |publisher=National Gallery of Victoria |access-date=12 February 2019 |language=en-AU}}</ref> highlights the lifelong squint (a [[Esotropia|form of strabismus]]) which prompted the name 'Guercino'.]] |

||

[[File:Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) - Christ and the Woman of Samaria - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|left|[[Caravaggio]]'s influence is apparent in this canvas ''Christ and the Woman of Samaria '' (c. |

[[File:Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) - Christ and the Woman of Samaria - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|left|[[Caravaggio]]'s influence is apparent in this canvas ''Christ and the Woman of Samaria '' (c. 1619–1620).]] |

||

[[File:Guercino - The Persian Sibyl - Google Art Project.jpg|thumbnail|Guercino – ''The Persian Sibyl'' ( |

[[File:Guercino - The Persian Sibyl - Google Art Project.jpg|thumbnail|Guercino – ''The Persian Sibyl'' (1647–48)]] |

||

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri was born into a family of [[peasant farmer]]s in [[Cento]], a town in the [[Po Valley]] mid-way between [[Bologna]] and [[Ferrara]].<ref name="Mahon1937a">Mahon, 1937a</ref> Being [[Strabismus|cross-eyed]], at an early age he acquired the nickname by which he is universally known, Guercino (a [[diminutive]] of the Italian noun |

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri was born into a family of [[peasant farmer]]s in [[Cento]], a town in the [[Po Valley]] mid-way between [[Bologna]] and [[Ferrara]].<ref name="Mahon1937a">Mahon, 1937a</ref> Being [[Strabismus|cross-eyed]], at an early age he acquired the nickname by which he is universally known, Guercino (a [[diminutive]] of the Italian noun {{lang|it|[[wikt:guercio|guercio]]}}, meaning 'squinter').<ref name="Oxford">Turner, 2003</ref> Mainly self-taught, at the age of 16, he worked as apprentice in the shop of [[Benedetto Gennari]], a painter of the [[Bolognese School (painting)|Bolognese School]].<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 6</ref> An early commission was for the decoration with frescos (1615–1616<ref>{{cite web |title=Casa Pannini di Cento |url=https://www.geoplan.it/luoghi-interesse-italia/monumenti-provincia-ferrara/cartina-monumenti-cento/monumenti-cento-casa-pannini.htm |website=www.geoplan.it |access-date=8 February 2019 |language=it}}</ref>) of Casa Pannini in Cento, where the [[Realism (arts)|naturalism]] of his [[Landscape painting#17th and 18th centuries|landscape]]s already reveals considerable artistic independence, as do his landscapes on canvas ''[[Moonlit Landscape]]'' and ''[[Country Concert]]'' from the same era.<ref>Stone, pp. 3, 37.</ref> In Bologna, he was winning the praise of [[Ludovico Carracci]]. He always acknowledged that his early style had been influenced by study of a Madonna painted by Ludovico Carracci for the Capuchin church in Cento, affectionately known as "La Carraccina".<ref>{{cite web |title=La Carraccina |url=http://bbcc.ibc.regione.emilia-romagna.it/pater/loadcard.do?id_card=164519 |website=bbcc.ibc.regione.emilia-romagna.it |publisher=Regione Emilia Romagna |access-date=9 February 2019 |language=it}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | ''[[William of Gellone|St William]] Receiving the Monastic Habit'' (1620, [[Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna]], Italy),<ref>{{cite web |title=San Guglielmo d'Aquitania riceve l'abito religioso da San Felice Vescovo. (Vestizione di San Guglielmo) |url=http://www.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it/it/content_page/40-sala-26-il-classicismo/52-san-guglielmo-d-aquitania-riceve-l-abito-religioso-da-san-felice-vescovo-br-vestizione-di-san-guglielmo.html |website=www.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it |access-date=13 February 2019 |language=it-it |archive-date=9 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180809150109/http://www.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it/it/content_page/40-sala-26-il-classicismo/52-san-guglielmo-d-aquitania-riceve-l-abito-religioso-da-san-felice-vescovo-br-vestizione-di-san-guglielmo.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> painted for St Gregory Church in Bologna, was Guercino's largest ecclesiastical commission at the time and is considered a high point of his early career.<ref name="Oxford"/> |

||

| ⚫ | His painting ''[[Et in Arcadia ego (Guercino)|Et in Arcadia ego]]'' from around 1618–1622 contains the first known usage anywhere of the Latin motto, [[Et in Arcadia ego|later taken up]] by [[Poussin]] and others, signifying that [[Memento mori|death lurks]] even in the most [[Arcadia (utopia)|idyllic setting]].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Lubbock |first1=Tom |title=Guercino: Et in Arcadia Ego ( |

||

| ⚫ | His painting ''[[Et in Arcadia ego (Guercino)|Et in Arcadia ego]]'' from around 1618–1622 contains the first known usage anywhere of the Latin motto, [[Et in Arcadia ego (Poussin)|later taken up]] by [[Poussin]] and others, signifying that [[Memento mori|death lurks]] even in the most [[Arcadia (utopia)|idyllic setting]].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Lubbock |first1=Tom |title=Guercino: Et in Arcadia Ego (1618–22) |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/great-works/guercino-et-in-arcadia-ego-1618-22-744410.html |access-date=7 February 2019 |work=The Independent |date=23 February 2007 |language=en}}</ref> The dramatic composition of this canvas (related to his ''Flaying of [[Marsyas]] by Apollo'' (1617–1618<ref>{{cite web |title=Palazzo Pitti: Galleria Palatina – Apollo e Marsia |url=http://www.abcfirenze.com/GalleriaFotografica.asp?tipo=U&RicM=309&Foto=GalleriaPalatina-D35.jpg |website=www.abcfirenze.com |language=it |access-date=2019-02-09 |archive-date=2023-03-29 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230329110135/http://www.abcfirenze.com/GalleriaFotografica.asp?tipo=U&RicM=309&Foto=GalleriaPalatina-D35.jpg |url-status=dead }}</ref>) created for [[Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany|The Grand Duke of Tuscany]], which shares the same pair of shepherds<ref>{{cite web |title=Et in Arcadia Ego by Guercino |url=https://www.wga.hu/html_m/g/guercino/0/arcadia.html |website=www.wga.hu |publisher=Web Gallery of Art |access-date=8 February 2019}}</ref>) is typical of Guercino's early works, which are often tumultuous in conception.<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 13</ref> He painted two large canvases, ''[[Samson]] Seized by Philistines'' (1619) and ''[[Elijah]] Fed by Ravens'' (1620), for Cardinal Serra, a Papal Legate to Ferrara.<ref>{{cite web |title=Samson Captured by the Philistines |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436603 |website=www.metmuseum.org |publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art |access-date=8 February 2019}}</ref><ref name="Vivian1971">Vivian, 1971</ref> Painted at a time when it is unlikely that Guercino could have seen [[Caravaggio]]'s work in Rome, these works nevertheless display a starkly naturalistic Caravaggesque style. |

||

==Rome== |

==Rome== |

||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

==Return to Bologna== |

==Return to Bologna== |

||

Following the death of Gregory XV in 1623, Guercino returned to his hometown of Cento. In 1626, he began his [[fresco]]es in the [[Piacenza|Duomo of Piacenza]]. The details of his career after 1629 are well documented in the account book, the ''Libro dei Conti di Casa Barbieri'', that Guercino and his brother [[Paolo Antonio Barbieri]], a notable painter of [[Still life#Seventeenth century|still life]]s, kept updated, and which has been preserved.<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 35</ref> Between 1618 and 1631, [[Giovanni Battista Pasqualini]] produced 67 engravings that document the early production of Guercino, which is not included in the ''Libro dei Conti''.<ref name="Gozzi2006">{{cite web |last1=Gozzi |first1=Fausto |title=Sacro e Profano nelle Incisioni da Guercino |url=http://docplayer.it/19262888-Sacro-e-profano-nelle-incisioni-da-guercino-cento-1590-1666.html |publisher=Culturalia |access-date=12 February 2019 |language=it |date=2006}}</ref> In 1642, following the death of his commercial rival [[Guido Reni]], Guercino moved his busy workshop to Bologna, where he was now able to take over Reni's role as the city's leading painter of sacred subjects. |

Following the death of Gregory XV in 1623, Guercino returned to his hometown of Cento. In 1626, he began his [[fresco]]es in the [[Piacenza|Duomo of Piacenza]]. The details of his career after 1629 are well documented in the account book, the ''Libro dei Conti di Casa Barbieri'', that Guercino and his brother [[Paolo Antonio Barbieri]], a notable painter of [[Still life#Seventeenth century|still life]]s, kept updated, and which has been preserved.<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 35</ref> Between 1618 and 1631, [[Giovanni Battista Pasqualini]] produced 67 engravings that document the early production of Guercino, which is not included in the ''Libro dei Conti''.<ref name="Gozzi2006">{{cite web |last1=Gozzi |first1=Fausto |title=Sacro e Profano nelle Incisioni da Guercino |url=http://docplayer.it/19262888-Sacro-e-profano-nelle-incisioni-da-guercino-cento-1590-1666.html |publisher=Culturalia |access-date=12 February 2019 |language=it |date=2006}}</ref> In 1642, following the death of his commercial rival [[Guido Reni]], Guercino moved his busy workshop to Bologna, where he was now able to take over Reni's role as the city's leading painter of sacred subjects. In 1655, the [[Franciscan Order]] of Reggio paid him 300 ducats for the altarpiece of ''Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Madonna and Child'' (now in [[Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art]], Kansas City).<ref name="smarth">{{cite web | title =Guercino's Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin | publisher =[[Smarthistory]] at [[Khan Academy]] | url =http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/guercino.html | access-date =March 15, 2013 | archive-date =November 2, 2014 | archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20141102030315/http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/guercino.html | url-status =dead }}</ref> The Corsini also paid him 300 ducats for the ''Flagellation of Christ'' painted in 1657. |

||

[[File:San salvatore, bo, int., tomba del guercino.JPG|thumb|Tomb of Guercino, [[Santissimo Salvatore, Bologna]]]] |

[[File:San salvatore, bo, int., tomba del guercino.JPG|thumb|Tomb of Guercino, [[Santissimo Salvatore, Bologna]]]] |

||

==Style== |

|||

==Works and pupils== |

|||

Guercino was remarkable for the extreme rapidity of his executions: he completed no fewer than 106 large altarpieces for churches, and his other paintings amount to about 144. He was also a prolific draftsman. His production includes many drawings, usually in ink, washed ink, or red chalk. Most of them were made as preparatory studies for his paintings, but he also drew landscapes, [[Genre works|genre subjects]], and caricatures for his own enjoyment. Guercino's drawings are known for their fluent style in which "rapid, calligraphic pen strokes combined with dots, dashes, and parallel hatching lines describe the forms".<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 36</ref> |

Guercino was remarkable for the extreme rapidity of his executions: he completed no fewer than 106 large altarpieces for churches, and his other paintings amount to about 144. He was also a prolific draftsman. His production includes many drawings, usually in ink, washed ink, or red chalk. Most of them were made as preparatory studies for his paintings, but he also drew landscapes, [[Genre works|genre subjects]], and caricatures for his own enjoyment. Guercino's drawings are known for their fluent style in which "rapid, calligraphic pen strokes combined with dots, dashes, and parallel hatching lines describe the forms".<ref>Griswold 1991, p. 36</ref> |

||

Despite presumably having [[monocular vision]] due to a [[Amblyopia#Strabismus|'lazy']] right eye, Guercino showed remarkable facility to [[Depth perception|imply depth]] in his works, perhaps assisted by an enhanced [[Contrast (vision)|perception of light and shade]] thanks to compensation by the healthy eye.<ref name="Scholtz2019">Scholtz et al, 2019</ref> Other artists with different types of strabismus include [[Rembrandt]], [[Dürer]], [[Degas]], [[Picasso]] and (possibly) [[Leonardo da Vinci]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tyler |first1=CW |title=Evidence That Leonardo da Vinci Had Strabismus. |journal=JAMA Ophthalmology |volume=137 |issue=1 |pages=82–86 |date=18 October 2018 |doi=10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3833 |pmid=30347053 |url=https://christophertyler.org/CWTyler/Art%20Investigations/ART%20PDFs/Tyler_JAMA-0_180017.pdf |pmc=6439801}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | Guercino continued to paint and teach until |

||

| ⚫ | His lively treatment of the [[Aurora (mythology)|Aurora myth]] (1621, [[Casino di Villa Boncompagni Ludovisi|Villa Aurora]], Rome, Italy), painted for the pope's nephew, Cardinal [[Ludovico Ludovisi]].<ref>Vodret and Gozzi, 2011, pp. 159–161</ref> challenges the more measured representation of the same subject [[Aurora (Guido Reni)|painted by Guido Reni]] at [[Palazzo Pallavicini-Rospigliosi|Palazzo Rospigliosi]] on behalf of a Ludovisi family [[Scipione Borghese|rival]] and makes a statement of political triumph.<ref>Unger, 2016, p. 9; {{cite web |title=Aurora by Guercino |url=https://www.wga.hu/html_m/g/guercino/3/05aurora.html |website=www.wga.hu |publisher=Web Gallery of Art |access-date=15 February 2019}}</ref> Some of his later works are closer to the style of Reni, and are painted with much greater luminosity and clarity than his early works with their prominent use of chiaroscuro. |

||

==Pupils== |

|||

| ⚫ | Guercino continued to paint and teach until the end of his life, amassing a notable fortune. He died on December 22, 1666, in Bologna.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) {{!}} The Vocation of Saint Aloysius (Luigi) Gonzaga |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436604 |access-date=2023-04-12 |website=The Metropolitan Museum of Art |language=en}}</ref> As he never married, his estate passed to his nephews and pupils, [[Benedetto Gennari II]] and [[Cesare Gennari]].<ref name="Oxford" /> Other pupils include [[Giulio Coralli]],<ref>Orlandi, 1719, p. 207</ref> [[Giuseppe Bonati]] of Ferrara,<ref>Orlandi, p. 207</ref> [[Cristoforo Serra]] of Cesena,<ref>Orlandi, p. 120.</ref> Father [[Cesare Pronti]] of Ferrara,<ref>Orlandi, p. 350.</ref> [[Sebastiano Ghezzi]],<ref>Orlandi, p. 399</ref> [[Sebastiano Bombelli]],<ref>Orlandi, p. 397.</ref> [[Lorenzo Bergonzoni]] of Bologna,<ref>Orlandi, p. 294.</ref> [[Francesco Paglia]] of Brescia.,<ref>Orlandi, p. 171</ref> [[Benedetto Zallone]] of Cento, [[Bartolomeo Caravoglia]],<ref>Lanzi, 1847, pp. 309–310</ref> [[Giuseppe Maria Galeppini]] of Forli, and [[Matteo Loves]]. |

||

==Works== |

==Works== |

||

<gallery |

<gallery mode=packed heights=220px> |

||

File:Moonlight Landscape (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri Guercino) - Nationalmuseum - 20163.tif|''Moonlit Landscape'' (c. 1616, oil on canvas, 55 × 71 cm, [[Nationalmuseum]], Stockholm, Sweden).<ref>{{cite web |title=Giovanni Francesco Barbieri Il Guercino |url=http://emp-web-84.zetcom.ch/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=artist&objectId=7953&viewType=detailView |website=emp-web-84.zetcom.ch |publisher=Nationalmuseum |access-date=11 February 2019}}</ref> An early, naturalistic landscape. |

File:Moonlight Landscape (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri Guercino) - Nationalmuseum - 20163.tif|''Moonlit Landscape'' (c. 1616, oil on canvas, 55 × 71 cm, [[Nationalmuseum]], Stockholm, Sweden).<ref>{{cite web |title=Giovanni Francesco Barbieri Il Guercino |url=http://emp-web-84.zetcom.ch/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=artist&objectId=7953&viewType=detailView |website=emp-web-84.zetcom.ch |publisher=Nationalmuseum |access-date=11 February 2019}}</ref> An early, naturalistic landscape. |

||

File:Guercino La mietitura.jpg|''Harvesting'' (1615–1617, fresco, transferred to canvas, 18 × 23.5 cm, Pinacoteca, Cento, Italy). One of the frescos created (with the assistance of [[Lorenzo Gennari]]<ref name="Mahon1937a"/>) for Casa Pannini in Cento.<ref>{{cite web |title=Barbieri Giovan Francesco, Mietitura |url=http://catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it/scheda/opera/58933/Barbieri%20Giovan%20Francesco%2C%20Mietitura |website=catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it |publisher=Fondazione Zeri, University of Bologna |access-date=11 February 2019}}</ref> |

File:Guercino La mietitura.jpg|''Harvesting'' (1615–1617, fresco, transferred to canvas, 18 × 23.5 cm, Pinacoteca, Cento, Italy). One of the frescos created (with the assistance of [[Lorenzo Gennari]]<ref name="Mahon1937a"/>) for Casa Pannini in Cento.<ref>{{cite web |title=Barbieri Giovan Francesco, Mietitura |url=http://catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it/scheda/opera/58933/Barbieri%20Giovan%20Francesco%2C%20Mietitura |website=catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it |publisher=Fondazione Zeri, University of Bologna |access-date=11 February 2019}}</ref> |

||

File:Susana y los viejos (Guercino).jpg|''Susanna and the Elders'' (1617, oil on canvas, 176 × 208 cm, [[Museo del Prado]], Madrid, Spain) was painted in Bologna for Cardinal [[Alessandro Ludovisi]], the future Pope Gregory XV.<ref>{{cite web |title=Susannah and the Elders - The Collection |url=https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/susanna-and-the-elders/9c9b3611-5c80-457d-a99a-e5580f3074e6 |website=Museo Nacional del Prado |access-date=11 February 2019 |language=en}}</ref> The dramatic dynamism of this early work contrasts with the studied classicism of the artist's later depiction of the same story in 1649–1650.<ref name="Posner1968">Posner, 1968</ref> |

File:Susana y los viejos (Guercino).jpg|''Susanna and the Elders'' (1617, oil on canvas, 176 × 208 cm, [[Museo del Prado]], Madrid, Spain) was painted in Bologna for Cardinal [[Alessandro Ludovisi]], the future Pope Gregory XV.<ref>{{cite web |title=Susannah and the Elders - The Collection |url=https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/susanna-and-the-elders/9c9b3611-5c80-457d-a99a-e5580f3074e6 |website=Museo Nacional del Prado |access-date=11 February 2019 |language=en}}</ref> The dramatic dynamism of this early work contrasts with the studied classicism of the artist's later depiction of the same story in 1649–1650.<ref name="Posner1968">Posner, 1968</ref> |

||

File:Samson Captured by the Philistines MET DT503.jpg|''Samson Seized by the Philistines'', 1619 This work |

File:Samson Captured by the Philistines MET DT503.jpg|''Samson Seized by the Philistines'', 1619 This work depicts the biblical scene where Samson is betrayed by his lover Delilah. Samson is at the center, though his face cannot be seen, and surrounding him are the Philistines who have come to blind him after cutting off his hair, his source of strength. |

||

</gallery> |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="170"> |

|||

File:Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, gen. Il Guercino - Gleichnis vom verlorenen Sohn - GG 253 - Kunsthistorisches Museum.jpg|''Return of the Prodigal Son'', 1619 |

File:Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, gen. Il Guercino - Gleichnis vom verlorenen Sohn - GG 253 - Kunsthistorisches Museum.jpg|''Return of the Prodigal Son'', 1619 |

||

File:Guercino Guglielmo d'Aquitania.jpg|''[[William of Gellone|St William]] Receiving the Monastic Habit'', 1620 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Guercino - Aurora - WGA10920.jpg|''Aurora'', 1621 (ceiling fresco, tempera), [[Casino di Villa Boncompagni Ludovisi|Villa Aurora]], Rome, Italy |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

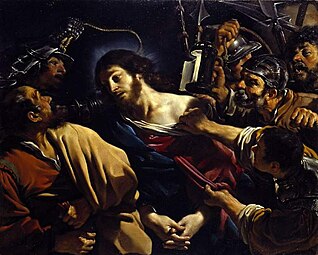

File:Guercino Catura di Cristo.jpg|''Capturing Christ'', 1621 |

File:Guercino Catura di Cristo.jpg|''Capturing Christ'', 1621 |

||

File:Guercino - Saint Matthew and the Angel - Google Art Project.jpg|''Saint Matthew and the Angel'', 1622 |

File:Guercino - Saint Matthew and the Angel - Google Art Project.jpg|''Saint Matthew and the Angel'', 1622 |

||

File:Guercino - Assumption of Mary - Hermitage.jpg|''[[Assumption (Guercino)|Assumption]]'', c. 1623, [[Hermitage Museum]] |

|||

File:Guercino_Morte_di_Didone.jpg|''La morte di Didone'', 1631 |

|||

File:Guercino Morte di Didone.jpg|''La morte di Didone'', 1631 |

|||

File:Guercino Christ et la samaritaine.jpg|''Christ and the Woman of Samaria'' II, c. 1640–1641 |

File:Guercino Christ et la samaritaine.jpg|''Christ and the Woman of Samaria'' II, c. 1640–1641 |

||

File:Guercino - ST. SEBASTIAN. 1642.jpg|''St. Sebastian'', 1642, [[Pushkin Museum]] |

|||

File:Atlas holding up the celestial globe - Guercino (1646).jpg|''Atlas holding up the celestial globe'', 1646 |

|||

File: |

File:Atlas holding up the celestial globe - Guercino (1646).jpg|''Atlas holding up the celestial globe'', 1646 |

||

File:Guercino - St Peter Weeping before the Virgin - WGA10949.jpg|''St Peter Weeping before the Virgin'', 1647 |

|||

File:Guercino - Mars with Cupid - Google Art Project.jpg|''Mars with Cupid'', 1649 |

File:Guercino - Mars with Cupid - Google Art Project.jpg|''Mars with Cupid'', 1649 |

||

File:Guercino - Cleopatra and Octavian - Google Art Project.jpg| |

File:Guercino - Cleopatra and Octavian - Google Art Project.jpg|''Cleopatra and Octavian'', 1649 |

||

File:Joseph and Potiphar's Wife - Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino, 1649 - NG Wash DC.jpg|''Joseph and Potiphar's Wife'', 1649, [[National Gallery of Art]] |

File:Joseph and Potiphar's Wife - Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino, 1649 - NG Wash DC.jpg|''Joseph and Potiphar's Wife'', 1649, [[National Gallery of Art]] |

||

File:Guercino - St. Cecilia - Google Art Project.jpg |

File:Guercino - St. Cecilia - Google Art Project.jpg|''St. Cecilia'', 1649 |

||

File:Guercino Susanna and The Elders Parma.jpg|''Susanna and the Elders'', 1650 |

File:Guercino Susanna and The Elders Parma.jpg|''Susanna and the Elders'', 1650 |

||

File:Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) - David with the Head of Goliath - Google Art Project.jpg|''David with the Head of Goliath'', circa 1650 |

File:Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) - David with the Head of Goliath - Google Art Project.jpg|''David with the Head of Goliath'', circa 1650 |

||

File:The Vocation of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga.PNG|''The Vocation of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga'', 1650 |

File:The Vocation of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga.PNG|''The Vocation of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga'', 1650 |

||

File:Guercino Astrologia.jpg|''Personification of Astrology'', ca. 1650–1655, [[Blanton Museum of Art]], [[Texas]] |

File:Guercino Astrologia.jpg|''Personification of Astrology'', ca. 1650–1655, [[Blanton Museum of Art]], [[Texas]] |

||

File:Guercino Return of the prodigal son.jpg| |

File:Guercino Return of the prodigal son.jpg|''The Return of the Prodigal Son'', 1651 |

||

File:'King David', painting by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (il Guercino) c. 1768.jpg|''King David'', 1651 |

File:'King David', painting by Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (il Guercino) c. 1768.jpg|''King David'', 1651 |

||

File:Guercino - Martyrdom of St Catherine - WGA10940.jpg|''[[The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine (Guercino)|The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine]]'', 1653, [[Hermitage Museum]] |

|||

Samson and Delilah mg 0034.jpg|''[[Samson and Delilah (Guercino)|Samson and Delilah]]'', 1654 |

File:Samson and Delilah mg 0034.jpg|''[[Samson and Delilah (Guercino)|Samson and Delilah]]'', 1654 |

||

File:Guercino, san girolamo penitente.JPG|''[[Saint Jerome (Guercino)|Saint Jerome]]'', c.1640–1650 |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 84: | Line 96: | ||

;Books and articles on Guercino |

;Books and articles on Guercino |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Griswold |first1=William M |title=Guercino |journal=Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin |date=1991|volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=5–56 |doi=10.2307/3258858 |jstor=3258858 |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Guercino_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_Bulletin_v_48_no_4_Spring_1991}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Griswold |first1=William M |title=Guercino |journal=Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin |date=1991|volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=5–56 |doi=10.2307/3258858 |jstor=3258858 |url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Guercino_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art_Bulletin_v_48_no_4_Spring_1991}} |

||

* {{cite book| first=Luigi| last=Lanzi| year=1847| title=History of Painting in Italy; From the Period of the Revival of the Fine Arts to the End of the Eighteenth Century|volume=III| |

* {{cite book| first=Luigi| last=Lanzi| year=1847| title=History of Painting in Italy; From the Period of the Revival of the Fine Arts to the End of the Eighteenth Century|volume=III| translator = [[Thomas Roscoe]]| publisher= Henry G. Bohn|location=London|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k0sGAAAAQAAJ| author-link=Luigi Lanzi}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Mahon |first1=Denis |author-link=Denis Mahon |title=Notes on the Young Guercino I. |

* {{cite journal |last1=Mahon |first1=Denis |author-link=Denis Mahon |title=Notes on the Young Guercino I. – Cento and Bologna |journal=The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs |date=1937a |volume=70 |issue=408 |pages=112–122 |jstor=866850}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Mahon |first1=Denis |title=Notes on the Young Guercino II. |

* {{cite journal |last1=Mahon |first1=Denis |title=Notes on the Young Guercino II. – Cento and Ferrara |journal=The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs |date=1937b |volume=70 |issue=409 |pages=177–189 |jstor=866750}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Mahon|first=Denis |title=Guercino: Master Painter of Baroque|url=https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002585966|year=1992|publisher=National Gallery of Art|isbn=978-0-89468-167-7}} |

* {{cite book|last=Mahon|first=Denis |title=Guercino: Master Painter of Baroque|url=https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/002585966|year=1992|publisher=National Gallery of Art|isbn=978-0-89468-167-7}} |

||

* {{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-francesco-detto-il-guercino-barbieri_(Dizionario-Biografico) |title=Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco detto il Guercino |first=Dwight C. |last=Miller |encyclopedia=Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani |language=it |volume=6 |year=1964}} |

* {{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-francesco-detto-il-guercino-barbieri_(Dizionario-Biografico) |title=Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco detto il Guercino |first=Dwight C. |last=Miller |encyclopedia=Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani |language=it |volume=6 |year=1964}} |

||

* {{citation|title=Abecedario pittorico|last1=Orlandi|first1=Pellegrino Antonio|last2=Guarienti|first2=Pietro|year=1719|place=Naples |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x3MGAAAAQAAJ}}. |

* {{citation|title=Abecedario pittorico|last1=Orlandi|first1=Pellegrino Antonio|last2=Guarienti|first2=Pietro|year=1719|place=Naples |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x3MGAAAAQAAJ}}. |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Posner |first1=Donald |title=The Guercino Exhibition at Bologna |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1968 |volume=110 |issue=788 |pages=596–607 |jstor=875813}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Posner |first1=Donald |title=The Guercino Exhibition at Bologna |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1968 |volume=110 |issue=788 |pages=596–607 |jstor=875813}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Scholtz |first1=Sibylle |last2=MacMorris |first2=Lee |last3=Krogmann |first3=Frank |last4=Auffarth |first4=Gerd U |title=Lights and darks of a picture. The life of Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, "il Guercino" |

* {{cite journal |last1=Scholtz |first1=Sibylle |last2=MacMorris |first2=Lee |last3=Krogmann |first3=Frank |last4=Auffarth |first4=Gerd U |title=Lights and darks of a picture. The life of Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, "il Guercino" – the squinter. |journal=Strabismus |date=2019 |pages=39–42 |doi=10.1080/09273972.2019.1559532 |pmid=30626256|url=http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0183-13doc1996 |volume=27|issue=1 |s2cid=58585811 }} {{subscription required}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=van Serooskerken |first1=Carel van Tuyll |title=Guercino. Bologna, Cento and Frankfurt |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1991 |volume=133 |issue=1065 |pages=864–868 |jstor=885077}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=van Serooskerken |first1=Carel van Tuyll |title=Guercino. Bologna, Cento and Frankfurt |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1991 |volume=133 |issue=1065 |pages=864–868 |jstor=885077}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Stone|first=David M |title=Guercino: Catalogo Completo Dei Dipinti |year=1991|publisher=Cantini|language=it|isbn=978-88-7737-137-9}} |

* {{cite book|last=Stone|first=David M |title=Guercino: Catalogo Completo Dei Dipinti |year=1991|publisher=Cantini|language=it|isbn=978-88-7737-137-9}} |

||

* {{cite encyclopedia |last1=Turner |first1=Nicholas |title=Oxford Art Online |chapter=Guercino |publisher=Oxford Art Online (Grove Art) |language=en |doi=10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t035416 |date=2003}} {{subscription}} |

* {{cite encyclopedia |last1=Turner |first1=Nicholas |title=Oxford Art Online |chapter=Guercino |publisher=Oxford Art Online (Grove Art) |language=en |doi=10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t035416 |date=2003|isbn=9781884446054 }} {{subscription required}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Unger|first=Daniel M|title=Guercino's Paintings and His Patrons' Politics in Early Modern Italy|date=2016| isbn=978-1-351-56482-3}} |

* {{cite book|last=Unger|first=Daniel M|title=Guercino's Paintings and His Patrons' Politics in Early Modern Italy|date=2016|publisher=Routledge | isbn=978-1-351-56482-3}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last1=Vivian |first1=Frances |title=Guercino Seen from the Archivio Barberini |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1971 |volume=113 |issue=814 |pages=22–29 |jstor=876502}} |

* {{cite journal |last1=Vivian |first1=Frances |title=Guercino Seen from the Archivio Barberini |journal=The Burlington Magazine |date=1971 |volume=113 |issue=814 |pages=22–29 |jstor=876502}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Vodret |first1=Rossella |last2=Gozzi |first2=Fausto |title=Guercino ( |

* {{cite book |last1=Vodret |first1=Rossella |last2=Gozzi |first2=Fausto |title=Guercino (1591–1666): capolavori da Cento e da Roma |date=2011 |publisher=Giunti |isbn=9788809775350 |language=it}} |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

| Line 103: | Line 115: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{external media | width = 154px | |

{{external media | width = 154px | float = right |

||

| headerimage=[[File:Guercino - St Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin - WGA10948.jpg|154px]] |

| headerimage=[[File:Guercino - St Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin - WGA10948.jpg|154px]] |

||

| video1 = [http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/guercino.html Guercino's ''Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin''], [[Smarthistory]]}} |

| video1 = [http://smarthistory.khanacademy.org/guercino.html Guercino's ''Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin''], [[Smarthistory]]}} |

||

{{Commons |

{{Commons}} |

||

{{Wikisource1911Enc|Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco}} |

{{Wikisource1911Enc|Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco}} |

||

*{{Art UK bio}} |

*{{Art UK bio}} |

||

| Line 117: | Line 129: | ||

* [http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15324coll10/id/63259/rec/2 ''Velázquez ''], an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Guercino (see index) |

* [http://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15324coll10/id/63259/rec/2 ''Velázquez ''], an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Guercino (see index) |

||

{{Guercino}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 125: | Line 138: | ||

[[Category:1666 deaths]] |

[[Category:1666 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:Italian male painters]] |

[[Category:Italian male painters]] |

||

[[Category:Italian Roman Catholics]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Cento]] |

[[Category:People from Cento]] |

||

[[Category:17th-century Italian painters]] |

[[Category:17th-century Italian painters]] |

||

[[Category:Catholic painters]] |

[[Category:Catholic painters]] |

||

[[Category:Catholic draughtsmen]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 22:14, 20 October 2024

Guercino | |

|---|---|

Self portrait, c. 1635 | |

| Born | Giovanni Francesco Barbieri February 8, 1591 |

| Died | December 22, 1666 (aged 75) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Painting, drawing |

| Movement | Baroque |

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (February 8, 1591 – December 22, 1666),[1] better known as (il) Guercino[2] (Italian pronunciation: [ɡwerˈtʃiːno] ⓘ), was an Italian Baroque painter and draftsman from Cento in the Emilia region, who was active in Rome and Bologna. The vigorous naturalism of his early manner contrasts with the classical equilibrium of his later works. His many drawings are noted for their luminosity and lively style.

Biography

[edit]

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri was born into a family of peasant farmers in Cento, a town in the Po Valley mid-way between Bologna and Ferrara.[4] Being cross-eyed, at an early age he acquired the nickname by which he is universally known, Guercino (a diminutive of the Italian noun guercio, meaning 'squinter').[5] Mainly self-taught, at the age of 16, he worked as apprentice in the shop of Benedetto Gennari, a painter of the Bolognese School.[6] An early commission was for the decoration with frescos (1615–1616[7]) of Casa Pannini in Cento, where the naturalism of his landscapes already reveals considerable artistic independence, as do his landscapes on canvas Moonlit Landscape and Country Concert from the same era.[8] In Bologna, he was winning the praise of Ludovico Carracci. He always acknowledged that his early style had been influenced by study of a Madonna painted by Ludovico Carracci for the Capuchin church in Cento, affectionately known as "La Carraccina".[9]

St William Receiving the Monastic Habit (1620, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna, Italy),[10] painted for St Gregory Church in Bologna, was Guercino's largest ecclesiastical commission at the time and is considered a high point of his early career.[5]

His painting Et in Arcadia ego from around 1618–1622 contains the first known usage anywhere of the Latin motto, later taken up by Poussin and others, signifying that death lurks even in the most idyllic setting.[11] The dramatic composition of this canvas (related to his Flaying of Marsyas by Apollo (1617–1618[12]) created for The Grand Duke of Tuscany, which shares the same pair of shepherds[13]) is typical of Guercino's early works, which are often tumultuous in conception.[14] He painted two large canvases, Samson Seized by Philistines (1619) and Elijah Fed by Ravens (1620), for Cardinal Serra, a Papal Legate to Ferrara.[15][16] Painted at a time when it is unlikely that Guercino could have seen Caravaggio's work in Rome, these works nevertheless display a starkly naturalistic Caravaggesque style.

Rome

[edit]

Guercino was recommended by Marchese Enzo Bentivoglio to the newly elected Bolognese Ludovisi Pope, Pope Gregory XV in 1621.[17] The years he spent in Rome, 1621–23, were very productive. From this period are his frescoes Aurora at the casino of the Villa Ludovisi, the ceiling in San Crisogono (1622) of San Chrysogonus in Glory, the portrait of Pope Gregory XV (now in the Getty Museum), and the St. Petronilla Altarpiece for St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican (now in the Museo Capitolini).

Return to Bologna

[edit]Following the death of Gregory XV in 1623, Guercino returned to his hometown of Cento. In 1626, he began his frescoes in the Duomo of Piacenza. The details of his career after 1629 are well documented in the account book, the Libro dei Conti di Casa Barbieri, that Guercino and his brother Paolo Antonio Barbieri, a notable painter of still lifes, kept updated, and which has been preserved.[18] Between 1618 and 1631, Giovanni Battista Pasqualini produced 67 engravings that document the early production of Guercino, which is not included in the Libro dei Conti.[19] In 1642, following the death of his commercial rival Guido Reni, Guercino moved his busy workshop to Bologna, where he was now able to take over Reni's role as the city's leading painter of sacred subjects. In 1655, the Franciscan Order of Reggio paid him 300 ducats for the altarpiece of Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Madonna and Child (now in Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City).[20] The Corsini also paid him 300 ducats for the Flagellation of Christ painted in 1657.

Style

[edit]Guercino was remarkable for the extreme rapidity of his executions: he completed no fewer than 106 large altarpieces for churches, and his other paintings amount to about 144. He was also a prolific draftsman. His production includes many drawings, usually in ink, washed ink, or red chalk. Most of them were made as preparatory studies for his paintings, but he also drew landscapes, genre subjects, and caricatures for his own enjoyment. Guercino's drawings are known for their fluent style in which "rapid, calligraphic pen strokes combined with dots, dashes, and parallel hatching lines describe the forms".[21]

Despite presumably having monocular vision due to a 'lazy' right eye, Guercino showed remarkable facility to imply depth in his works, perhaps assisted by an enhanced perception of light and shade thanks to compensation by the healthy eye.[22] Other artists with different types of strabismus include Rembrandt, Dürer, Degas, Picasso and (possibly) Leonardo da Vinci.[23]

His lively treatment of the Aurora myth (1621, Villa Aurora, Rome, Italy), painted for the pope's nephew, Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi.[24] challenges the more measured representation of the same subject painted by Guido Reni at Palazzo Rospigliosi on behalf of a Ludovisi family rival and makes a statement of political triumph.[25] Some of his later works are closer to the style of Reni, and are painted with much greater luminosity and clarity than his early works with their prominent use of chiaroscuro.

Pupils

[edit]Guercino continued to paint and teach until the end of his life, amassing a notable fortune. He died on December 22, 1666, in Bologna.[26] As he never married, his estate passed to his nephews and pupils, Benedetto Gennari II and Cesare Gennari.[5] Other pupils include Giulio Coralli,[27] Giuseppe Bonati of Ferrara,[28] Cristoforo Serra of Cesena,[29] Father Cesare Pronti of Ferrara,[30] Sebastiano Ghezzi,[31] Sebastiano Bombelli,[32] Lorenzo Bergonzoni of Bologna,[33] Francesco Paglia of Brescia.,[34] Benedetto Zallone of Cento, Bartolomeo Caravoglia,[35] Giuseppe Maria Galeppini of Forli, and Matteo Loves.

Works

[edit]-

Moonlit Landscape (c. 1616, oil on canvas, 55 × 71 cm, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).[36] An early, naturalistic landscape.

-

Harvesting (1615–1617, fresco, transferred to canvas, 18 × 23.5 cm, Pinacoteca, Cento, Italy). One of the frescos created (with the assistance of Lorenzo Gennari[4]) for Casa Pannini in Cento.[37]

-

Susanna and the Elders (1617, oil on canvas, 176 × 208 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain) was painted in Bologna for Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, the future Pope Gregory XV.[38] The dramatic dynamism of this early work contrasts with the studied classicism of the artist's later depiction of the same story in 1649–1650.[39]

-

Samson Seized by the Philistines, 1619 This work depicts the biblical scene where Samson is betrayed by his lover Delilah. Samson is at the center, though his face cannot be seen, and surrounding him are the Philistines who have come to blind him after cutting off his hair, his source of strength.

-

Return of the Prodigal Son, 1619

-

St William Receiving the Monastic Habit, 1620

-

Aurora, 1621 (ceiling fresco, tempera), Villa Aurora, Rome, Italy

-

Capturing Christ, 1621

-

Saint Matthew and the Angel, 1622

-

Assumption, c. 1623, Hermitage Museum

-

La morte di Didone, 1631

-

Christ and the Woman of Samaria II, c. 1640–1641

-

St. Sebastian, 1642, Pushkin Museum

-

Atlas holding up the celestial globe, 1646

-

St Peter Weeping before the Virgin, 1647

-

Mars with Cupid, 1649

-

Cleopatra and Octavian, 1649

-

Joseph and Potiphar's Wife, 1649, National Gallery of Art

-

St. Cecilia, 1649

-

Susanna and the Elders, 1650

-

David with the Head of Goliath, circa 1650

-

The Vocation of Saint Aloysius Gonzaga, 1650

-

Personification of Astrology, ca. 1650–1655, Blanton Museum of Art, Texas

-

The Return of the Prodigal Son, 1651

-

King David, 1651

-

Samson and Delilah, 1654

-

Saint Jerome, c.1640–1650

Exhibitions

[edit]A groundbreaking exhibition held at the Archiginnasio of Bologna in 1968 provided the most complete panorama of Guercino's work to date, including paintings from the later parts of his career after the death of Pope Gregory XV, which had previously attracted relatively little attention.[39] For the fourth centenary of the artist's birth in 1991, an expanded exhibition was organized by the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna in conjunction with the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt and the National Gallery of Art, Washington.[40] Both these exhibitions were curated by Guercino's biggest modern champion, Denis Mahon, who was responsible for their catalogues.[41] In 2011–2012, a large exhibition was displayed at Palazzo Barberini in Rome, dedicated to the memory of Mahon, who had recently died.[42] An exhibition displayed at the National Museum in Warsaw in 2013–2014 offered another extensive presentation of the artist's work.[43]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Miller, 1964

- ^ "Beside the easel". besidetheeasel.blogspot.se. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ "Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, called Guercino – Ottavio Leoni". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b Mahon, 1937a

- ^ a b c Turner, 2003

- ^ Griswold 1991, p. 6

- ^ "Casa Pannini di Cento". www.geoplan.it (in Italian). Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Stone, pp. 3, 37.

- ^ "La Carraccina". bbcc.ibc.regione.emilia-romagna.it (in Italian). Regione Emilia Romagna. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- ^ "San Guglielmo d'Aquitania riceve l'abito religioso da San Felice Vescovo. (Vestizione di San Guglielmo)". www.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ Lubbock, Tom (23 February 2007). "Guercino: Et in Arcadia Ego (1618–22)". The Independent. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "Palazzo Pitti: Galleria Palatina – Apollo e Marsia". www.abcfirenze.com (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- ^ "Et in Arcadia Ego by Guercino". www.wga.hu. Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Griswold 1991, p. 13

- ^ "Samson Captured by the Philistines". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ Vivian, 1971

- ^ Lawrence Gowing, ed., Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists, v.2 (Facts on File, 2005): 291.

- ^ Griswold 1991, p. 35

- ^ Gozzi, Fausto (2006). "Sacro e Profano nelle Incisioni da Guercino" (in Italian). Culturalia. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Guercino's Saint Luke Displaying a Painting of the Virgin". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ^ Griswold 1991, p. 36

- ^ Scholtz et al, 2019

- ^ Tyler, CW (18 October 2018). "Evidence That Leonardo da Vinci Had Strabismus" (PDF). JAMA Ophthalmology. 137 (1): 82–86. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.3833. PMC 6439801. PMID 30347053.

- ^ Vodret and Gozzi, 2011, pp. 159–161

- ^ Unger, 2016, p. 9; "Aurora by Guercino". www.wga.hu. Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ "Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) | The Vocation of Saint Aloysius (Luigi) Gonzaga". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ Orlandi, 1719, p. 207

- ^ Orlandi, p. 207

- ^ Orlandi, p. 120.

- ^ Orlandi, p. 350.

- ^ Orlandi, p. 399

- ^ Orlandi, p. 397.

- ^ Orlandi, p. 294.

- ^ Orlandi, p. 171

- ^ Lanzi, 1847, pp. 309–310

- ^ "Giovanni Francesco Barbieri Il Guercino". emp-web-84.zetcom.ch. Nationalmuseum. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Barbieri Giovan Francesco, Mietitura". catalogo.fondazionezeri.unibo.it. Fondazione Zeri, University of Bologna. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ "Susannah and the Elders - The Collection". Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ a b Posner, 1968

- ^ Mahon, 1992, p. 7

- ^ van Serooskerken, 1991

- ^ Vodret and Gozzi, 2011

- ^ "Guercino. Triumf baroku" [Guercino. Triumph of the Baroque]. www.legitymizm.org (in Polish). Organizacja Monarchistów Polskich. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

References

[edit]- Books and articles on Guercino

- Griswold, William M (1991). "Guercino". Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 48 (4): 5–56. doi:10.2307/3258858. JSTOR 3258858.

- Lanzi, Luigi (1847). History of Painting in Italy; From the Period of the Revival of the Fine Arts to the End of the Eighteenth Century. Vol. III. Translated by Thomas Roscoe. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Mahon, Denis (1937a). "Notes on the Young Guercino I. – Cento and Bologna". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 70 (408): 112–122. JSTOR 866850.

- Mahon, Denis (1937b). "Notes on the Young Guercino II. – Cento and Ferrara". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 70 (409): 177–189. JSTOR 866750.

- Mahon, Denis (1992). Guercino: Master Painter of Baroque. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-167-7.

- Miller, Dwight C. (1964). "Barbieri, Giovanni Francesco detto il Guercino". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 6.

- Orlandi, Pellegrino Antonio; Guarienti, Pietro (1719), Abecedario pittorico, Naples.

- Posner, Donald (1968). "The Guercino Exhibition at Bologna". The Burlington Magazine. 110 (788): 596–607. JSTOR 875813.

- Scholtz, Sibylle; MacMorris, Lee; Krogmann, Frank; Auffarth, Gerd U (2019). "Lights and darks of a picture. The life of Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, "il Guercino" – the squinter". Strabismus. 27 (1): 39–42. doi:10.1080/09273972.2019.1559532. PMID 30626256. S2CID 58585811. (subscription required)

- van Serooskerken, Carel van Tuyll (1991). "Guercino. Bologna, Cento and Frankfurt". The Burlington Magazine. 133 (1065): 864–868. JSTOR 885077.

- Stone, David M (1991). Guercino: Catalogo Completo Dei Dipinti (in Italian). Cantini. ISBN 978-88-7737-137-9.

- Turner, Nicholas (2003). "Guercino". Oxford Art Online. Oxford Art Online (Grove Art). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t035416. ISBN 9781884446054. (subscription required)

- Unger, Daniel M (2016). Guercino's Paintings and His Patrons' Politics in Early Modern Italy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-56482-3.

- Vivian, Frances (1971). "Guercino Seen from the Archivio Barberini". The Burlington Magazine. 113 (814): 22–29. JSTOR 876502.

- Vodret, Rossella; Gozzi, Fausto (2011). Guercino (1591–1666): capolavori da Cento e da Roma (in Italian). Giunti. ISBN 9788809775350.

Further reading

[edit]- Amorini, Antonio Bolognini (1843). "Parte Quinta". Vite de Pittori ed Artifici Bolognesi (in Italian). Tipografia Governativa alla Volpe, Bologna. pp. 223–272.

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

- 53 artworks by or after Guercino at the Art UK site

- Paintings by Guercino on the Web Gallery of Art

- Getty exhibition of Guercino drawings

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Il Guercino

- Pinacoteca Civica Il Guercino

- Virtual exhibition "Guercino a Fano" in high resolution

- Jusepe de Ribera, 1591–1652, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Guercino (see index)

- Velázquez , an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Guercino (see index)

![Moonlit Landscape (c. 1616, oil on canvas, 55 × 71 cm, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden).[36] An early, naturalistic landscape.](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/Moonlight_Landscape_%28Giovanni_Francesco_Barbieri_Guercino%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_20163.tif/lossy-page1-427px-Moonlight_Landscape_%28Giovanni_Francesco_Barbieri_Guercino%29_-_Nationalmuseum_-_20163.tif.jpg)

![Harvesting (1615–1617, fresco, transferred to canvas, 18 × 23.5 cm, Pinacoteca, Cento, Italy). One of the frescos created (with the assistance of Lorenzo Gennari[4]) for Casa Pannini in Cento.[37]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/1/1b/Guercino_La_mietitura.jpg)

![Susanna and the Elders (1617, oil on canvas, 176 × 208 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain) was painted in Bologna for Cardinal Alessandro Ludovisi, the future Pope Gregory XV.[38] The dramatic dynamism of this early work contrasts with the studied classicism of the artist's later depiction of the same story in 1649–1650.[39]](/upwiki/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Susana_y_los_viejos_%28Guercino%29.jpg/393px-Susana_y_los_viejos_%28Guercino%29.jpg)