Right angle: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Fgnievinski (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 29 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|90° angle (π/2 radians) |

{{short description|90° angle (π/2 radians)}} |

||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

[[Image:Right f a straight line}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

[[Image:Right angle.svg|thumb|134px|A right angle is equal to 90 degrees.]] |

[[Image:Right angle.svg|thumb|134px|A right angle is equal to 90 degrees.]] |

||

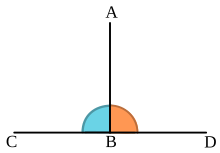

[[Image:Perpendicular-coloured.svg|right|thumb|A line segment (AB) drawn so that it forms right angles with a line (CD) |

[[Image:Perpendicular-coloured.svg|right|thumb|A line segment (AB) drawn so that it forms right angles with a line (CD)]] |

||

{{Angles}} |

|||

In [[geometry]] and [[trigonometry]], a '''right angle''' is an [[angle]] of exactly 90[[Degree (angle)| |

In [[geometry]] and [[trigonometry]], a '''right angle''' is an [[angle]] of exactly 90 [[Degree (angle)|degrees]] or {{sfrac|<math>\pi</math>|2}} [[radian]]s<ref>{{cite web|title=Right Angle|url=http://www.mathopenref.com/angleright.html|website=Math Open Reference|access-date=26 April 2017}}</ref> corresponding to a quarter [[turn (geometry)|turn]].<ref>Wentworth p. 11</ref> If a [[Line (mathematics)#Ray|ray]] is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the adjacent angles are equal, then they are right angles.<ref>Wentworth p. 8</ref> The term is a [[calque]] of [[Latin]] ''angulus rectus''; here ''rectus'' means "upright", referring to the vertical perpendicular to a horizontal base line. |

||

Closely related and important geometrical concepts are [[perpendicular]] lines, meaning lines that form right angles at their point of intersection, and [[orthogonality]], which is the property of forming right angles, usually applied to [[Euclidean vector|vectors]]. The presence of a right angle in a [[triangle]] is the defining factor for [[right triangle]]s,<ref>Wentworth p. 40</ref> making the right angle basic to trigonometry. |

Closely related and important geometrical concepts are [[perpendicular]] lines, meaning lines that form right angles at their point of intersection, and [[orthogonality]], which is the property of forming right angles, usually applied to [[Euclidean vector|vectors]]. The presence of a right angle in a [[triangle]] is the defining factor for [[right triangle]]s,<ref>Wentworth p. 40</ref> making the right angle basic to trigonometry. |

||

== Etymology == |

== Etymology == |

||

The meaning of |

The meaning of ''right'' in ''right angle'' possibly refers to the [[Classical Latin|Latin]] adjective ''rectus'' 'erect, straight, upright, perpendicular'. A [[Greek language|Greek]] equivalent is ''orthos'' 'straight; perpendicular' (see [[orthogonality]]). |

||

== In elementary geometry == |

== In elementary geometry == |

||

| Line 19: | Line 18: | ||

== Symbols == |

== Symbols == |

||

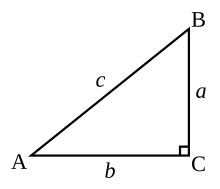

[[Image:Rtriangle.svg|thumb|Right triangle, with the right angle shown via a small square |

[[Image:Rtriangle.svg|thumb|Right triangle, with the right angle shown via a small square]] |

||

[[File:Triangle 30-60-90 rotated.png|thumb|Another option of diagrammatically indicating a right angle, using an angle curve and a small dot |

[[File:Triangle 30-60-90 rotated.png|thumb|Another option of diagrammatically indicating a right angle, using an angle curve and a small dot]] |

||

In [[Unicode]], the symbol for a right angle is {{unichar|221f|Right angle|html=}}. It should not be confused with the similarly shaped symbol {{unichar|231e|Bottom left corner|html=}}. Related symbols are {{unichar|22be|Right angle with arc|html=}}, {{unichar|299c|Right angle variant with square|html=}}, and {{unichar|299d|Measured right angle with dot|html=}}.<ref>Unicode 5.2 Character Code Charts [https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2200.pdf Mathematical Operators], [https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2980.pdf Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-B]</ref> |

In [[Unicode]], the symbol for a right angle is {{unichar|221f|Right angle|html=}}. It should not be confused with the similarly shaped symbol {{unichar|231e|Bottom left corner|html=}}. Related symbols are {{unichar|22be|Right angle with arc|html=}}, {{unichar|299c|Right angle variant with square|html=}}, and {{unichar|299d|Measured right angle with dot|html=}}.<ref>Unicode 5.2 Character Code Charts [https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2200.pdf Mathematical Operators], [https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U2980.pdf Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-B]</ref> |

||

| Line 29: | Line 28: | ||

Right angles are fundamental in [[Euclid's Elements]]. They are defined in Book 1, definition 10, which also defines perpendicular lines. Definition 10 does not use numerical degree measurements but rather touches at the very heart of what a right angle is, namely two straight lines intersecting to form two equal and adjacent angles.<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> The straight lines which form right angles are called perpendicular.<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> Euclid uses right angles in definitions 11 and 12 to define acute angles (those smaller than a right angle) and obtuse angles (those greater than a right angle).<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> Two angles are called [[Complementary angles|complementary]] if their sum is a right angle.<ref>Wentworth p. 9</ref> |

Right angles are fundamental in [[Euclid's Elements]]. They are defined in Book 1, definition 10, which also defines perpendicular lines. Definition 10 does not use numerical degree measurements but rather touches at the very heart of what a right angle is, namely two straight lines intersecting to form two equal and adjacent angles.<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> The straight lines which form right angles are called perpendicular.<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> Euclid uses right angles in definitions 11 and 12 to define acute angles (those smaller than a right angle) and obtuse angles (those greater than a right angle).<ref>Heath p. 181</ref> Two angles are called [[Complementary angles|complementary]] if their sum is a right angle.<ref>Wentworth p. 9</ref> |

||

Book 1 Postulate 4 states that all right angles are equal, which allows Euclid to use a right angle as a unit to measure other angles with. Euclid's commentator [[Proclus]] gave a proof of this postulate using the previous postulates, but it may be argued that this proof makes use of some hidden assumptions. [[Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri|Saccheri]] gave a proof as well but using a more explicit assumption. In [[David Hilbert|Hilbert]]'s [[Hilbert's axioms|axiomatization of geometry]] this statement is given as a theorem, but only after much groundwork. One may argue that, even if postulate 4 can be proven from the preceding ones, in the order that Euclid presents his material it is necessary to include it since without it postulate 5, which uses the right angle as a unit of measure, makes no sense.<ref>Heath pp. |

Book 1 Postulate 4 states that all right angles are equal, which allows Euclid to use a right angle as a unit to measure other angles with. Euclid's commentator [[Proclus]] gave a proof of this postulate using the previous postulates, but it may be argued that this proof makes use of some hidden assumptions. [[Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri|Saccheri]] gave a proof as well but using a more explicit assumption. In [[David Hilbert|Hilbert]]'s [[Hilbert's axioms|axiomatization of geometry]] this statement is given as a theorem, but only after much groundwork. One may argue that, even if postulate 4 can be proven from the preceding ones, in the order that Euclid presents his material it is necessary to include it since without it postulate 5, which uses the right angle as a unit of measure, makes no sense.<ref>Heath pp. 200–201 for the paragraph</ref> |

||

== Conversion to other units == |

== Conversion to other units == |

||

| Line 35: | Line 34: | ||

* {{sfrac|1|4}} [[turn (geometry)|turn]] |

* {{sfrac|1|4}} [[turn (geometry)|turn]] |

||

* 90° ([[Degree (angle)|degrees]]) |

* 90° ([[Degree (angle)|degrees]]) |

||

* {{sfrac|π|2}} [[radian]]s |

* {{sfrac|π|2}} [[radian]]s |

||

* 100 [[Grad (angle)|grad]] (also called ''grade'', ''gradian'', or ''gon'') |

* 100 [[Grad (angle)|grad]] (also called ''grade'', ''gradian'', or ''gon'') |

||

* 8 points (of a 32-point [[compass rose]]) |

* 8 points (of a 32-point [[compass rose]]) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 40: | ||

== Rule of 3-4-5 == |

== Rule of 3-4-5 == |

||

Throughout history, carpenters and masons have known a quick way to confirm if an angle is a true |

Throughout history, carpenters and masons have known a quick way to confirm if an angle is a true right angle. It is based on the [[Pythagorean triple]] {{nowrap|(3, 4, 5)}} and the rule of 3-4-5. From the angle in question, running a straight line along one side exactly three units in length, and along the second side exactly four units in length, will create a [[hypotenuse]] (the longer line opposite the right angle that connects the two measured endpoints) of exactly five units in length. |

||

== Thales' theorem == |

== Thales' theorem == |

||

| Line 61: | Line 60: | ||

Two application examples in which the right angle and the Thales' theorem are included (see animations). |

Two application examples in which the right angle and the Thales' theorem are included (see animations). |

||

== Generalizations == |

|||

The [[solid angle]] subtended by an [[octant of a sphere]] (the spherical triangle with three right angles) equals {{pi}}/2 [[steradian|sr]].<ref name="u421">{{cite web | title=octant | website=PlanetMath.org | date=2013-03-22 | url=https://planetmath.org/octant | access-date=2024-10-21}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

{{Commons category|Right angles}} |

{{Commons category|Right angles}} |

||

*[[Cartesian coordinate system]] |

*[[Cartesian coordinate system]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Perpendicular]] |

|||

*[[Rectangle]] |

|||

*[[Angle#Types of angles|Types of angles]] |

*[[Angle#Types of angles|Types of angles]] |

||

| Line 79: | Line 78: | ||

[[Category:Angle]] |

[[Category:Angle]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Latest revision as of 05:42, 21 October 2024

| Types of angles |

|---|

| 2D angles |

| Spherical |

| 2D angle pairs |

|

Adjacent |

| 3D angles |

| Solid |

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 degrees or /2 radians[1] corresponding to a quarter turn.[2] If a ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the adjacent angles are equal, then they are right angles.[3] The term is a calque of Latin angulus rectus; here rectus means "upright", referring to the vertical perpendicular to a horizontal base line.

Closely related and important geometrical concepts are perpendicular lines, meaning lines that form right angles at their point of intersection, and orthogonality, which is the property of forming right angles, usually applied to vectors. The presence of a right angle in a triangle is the defining factor for right triangles,[4] making the right angle basic to trigonometry.

Etymology

[edit]The meaning of right in right angle possibly refers to the Latin adjective rectus 'erect, straight, upright, perpendicular'. A Greek equivalent is orthos 'straight; perpendicular' (see orthogonality).

In elementary geometry

[edit]A rectangle is a quadrilateral with four right angles. A square has four right angles, in addition to equal-length sides.

The Pythagorean theorem states how to determine when a triangle is a right triangle.

Symbols

[edit]

In Unicode, the symbol for a right angle is U+221F ∟ RIGHT ANGLE (∟). It should not be confused with the similarly shaped symbol U+231E ⌞ BOTTOM LEFT CORNER (⌞, ⌞). Related symbols are U+22BE ⊾ RIGHT ANGLE WITH ARC (⊾), U+299C ⦜ RIGHT ANGLE VARIANT WITH SQUARE (⦜), and U+299D ⦝ MEASURED RIGHT ANGLE WITH DOT (⦝).[5]

In diagrams, the fact that an angle is a right angle is usually expressed by adding a small right angle that forms a square with the angle in the diagram, as seen in the diagram of a right triangle (in British English, a right-angled triangle) to the right. The symbol for a measured angle, an arc, with a dot, is used in some European countries, including German-speaking countries and Poland, as an alternative symbol for a right angle.[6]

Euclid

[edit]Right angles are fundamental in Euclid's Elements. They are defined in Book 1, definition 10, which also defines perpendicular lines. Definition 10 does not use numerical degree measurements but rather touches at the very heart of what a right angle is, namely two straight lines intersecting to form two equal and adjacent angles.[7] The straight lines which form right angles are called perpendicular.[8] Euclid uses right angles in definitions 11 and 12 to define acute angles (those smaller than a right angle) and obtuse angles (those greater than a right angle).[9] Two angles are called complementary if their sum is a right angle.[10]

Book 1 Postulate 4 states that all right angles are equal, which allows Euclid to use a right angle as a unit to measure other angles with. Euclid's commentator Proclus gave a proof of this postulate using the previous postulates, but it may be argued that this proof makes use of some hidden assumptions. Saccheri gave a proof as well but using a more explicit assumption. In Hilbert's axiomatization of geometry this statement is given as a theorem, but only after much groundwork. One may argue that, even if postulate 4 can be proven from the preceding ones, in the order that Euclid presents his material it is necessary to include it since without it postulate 5, which uses the right angle as a unit of measure, makes no sense.[11]

Conversion to other units

[edit]A right angle may be expressed in different units:

- 1/4 turn

- 90° (degrees)

- π/2 radians

- 100 grad (also called grade, gradian, or gon)

- 8 points (of a 32-point compass rose)

- 6 hours (astronomical hour angle)

Rule of 3-4-5

[edit]Throughout history, carpenters and masons have known a quick way to confirm if an angle is a true right angle. It is based on the Pythagorean triple (3, 4, 5) and the rule of 3-4-5. From the angle in question, running a straight line along one side exactly three units in length, and along the second side exactly four units in length, will create a hypotenuse (the longer line opposite the right angle that connects the two measured endpoints) of exactly five units in length.

Thales' theorem

[edit]Thales' theorem states that an angle inscribed in a semicircle (with a vertex on the semicircle and its defining rays going through the endpoints of the semicircle) is a right angle.

Two application examples in which the right angle and the Thales' theorem are included (see animations).

Generalizations

[edit]The solid angle subtended by an octant of a sphere (the spherical triangle with three right angles) equals π/2 sr.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Right Angle". Math Open Reference. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Wentworth p. 11

- ^ Wentworth p. 8

- ^ Wentworth p. 40

- ^ Unicode 5.2 Character Code Charts Mathematical Operators, Miscellaneous Mathematical Symbols-B

- ^ Müller-Philipp, Susanne; Gorski, Hans-Joachim (2011). Leitfaden Geometrie [Handbook Geometry] (in German). Springer. ISBN 9783834886163.

- ^ Heath p. 181

- ^ Heath p. 181

- ^ Heath p. 181

- ^ Wentworth p. 9

- ^ Heath pp. 200–201 for the paragraph

- ^ "octant". PlanetMath.org. 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- Wentworth, G.A. (1895). A Text-Book of Geometry. Ginn & Co.

- Euclid, commentary and trans. by T. L. Heath Elements Vol. 1 (1908 Cambridge) Google Books