False relation: Difference between revisions

m Standard headings/general fixes |

Brian Ammon (talk | contribs) →External links: Add Youtube link |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 28 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Type of dissonance in polyphonic music}} |

|||

A '''false relation''' (also known as '''cross-relation''', '''non-harmonic relation''') is the name of a type of dissonance that sometimes occurs in |

A '''false relation''' (also known as '''cross-relation''', '''non-harmonic relation''') is the name of a type of [[Consonance and dissonance|dissonance]] that sometimes occurs in [[Polyphony|polyphonic]] music, most commonly in vocal music of the [[Renaissance music|Renaissance]] and particularly in English music into the eighteenth century. |

||

The term describes |

The term describes a "[[diatonic and chromatic|chromatic]] contradiction"<ref name = "one">{{Cite Grove |last=Dyson |first=George |title=False relation}}</ref> between two [[note (music)|notes]] sounding simultaneously (or in close proximity) in two different [[melody|voices]] or parts; or alternatively, in music written before 1600, the occurrence of a [[tritone]] between two notes of adjacent [[chord (music)|chords]].<ref>Arnold Whittall (2002). "False Relation", ''The Oxford Companion to Music''. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford University Press. King's College London. [http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t114.e2404 Oxford Reference Online]. Accessed 18 March 2007.</ref> |

||

[[Image:False relation byrd.svg|center|thumb|400px|Ex. 1, from ''[[Ave Verum Corpus]]'', by [[William Byrd]]. {{audio|False relation byrd.mid|Play}}]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Image: |

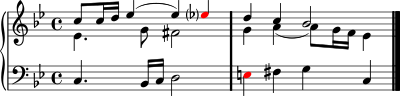

[[Image:Baroque false relation.svg|center|thumb|400px|Ex. 2, typical example of a false relation in the Late Baroque Style. {{audio|Baroque false relation.mid|Play}}]] |

||

| ⚫ | In this instance, the false relation is less pronounced: the contradicting E{{music|b}} (soprano voice) and E{{music|natural}} (bass voice) ([[diminished octave]]) do not sound simultaneously. Here the false relation occurs because the top voice is descending in a minor key, and therefore takes the notes of the [[natural minor]] scale descending (the diatonic sixth degree). The bass voice ascends and therefore makes use of the ascending melodic minor scale (the raised sixth degree). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | False relation is in this case desirable since this chromatic alteration follows a melodic idea, the rising 'melodic minor'. In such cases false relations must occur between different voices, as it follows that they cannot be produced by the semitones that occur diatonically in a mode or scale of any kind. This horizontal approach to polyphonic writing reflects the practices of composers in the [[Renaissance music|Renaissance]] and [[Tudor music|Tudor]] periods, particularly in vocal composition, but it is also seen, for example, in the [[hexachord]] fantasies of [[William Byrd]] (for keyboard). Indeed, vocal music from this era does not often have these [[accidental (music)|accidentals]] notated in the manuscript (see [[Musica ficta]]);<ref>{{Cite Grove |last=Bent |first=Margaret |title=Musica ficta, §1: Introduction}}</ref> experienced singers would have decided whether or not they were appropriate in a given musical context. |

||

| ⚫ | Many composers from the late 16th century onwards however began using the effect deliberately as an expressive device in their word setting. This practice continued well into the [[Romantic music|Romantic]] era, and can be heard in the music of [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]] and [[Frédéric Chopin|Chopin]], for example.<ref name="one"/> |

||

[[Image:Baroque_false_relation.JPG|center|thumb|800px|Ex. 2, typical example of a false relation in the Late Baroque Style]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In this instance, the false relation is less pronounced: the contradicting |

||

*[[English cadence]] |

|||

*[[Voice leading]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

| ⚫ | False relation is |

||

{{reflist}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

| ⚫ | Many composers from the late 16th century onwards however began |

||

| ⚫ | *Luís Henriques (Saturday, July 21, 2007). [http://musicologicus.blogspot.com/2007/07/william-byrd-ave-verum-corpus.html "William Byrd - ''Ave Verum Corpus''"], ''Atrium Musicologicum''. Another description of the use of false relation in Byrd's ''Ave Verum Corpus''. [This blog is open to invited readers only] |

||

* Early Music Sources ([[Elam Rotem]]): {{YouTube|id=uOoonFUb5HA|title=False relations in the late Renaissance}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

<div class="references-small"> |

|||

<references /> |

|||

</div> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Chromaticism}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Counterpoint & polyphony}} |

|||

[[Category:Harmony|False relation]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Chromaticism]] |

|||

[[de:Querstand (Musik)]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[fr:Fausse relation]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Harmony]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[nl:Querstand]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:13, 24 October 2024

A false relation (also known as cross-relation, non-harmonic relation) is the name of a type of dissonance that sometimes occurs in polyphonic music, most commonly in vocal music of the Renaissance and particularly in English music into the eighteenth century. The term describes a "chromatic contradiction"[1] between two notes sounding simultaneously (or in close proximity) in two different voices or parts; or alternatively, in music written before 1600, the occurrence of a tritone between two notes of adjacent chords.[2]

In the above example, a chromatic false relation occurs in two adjacent voices sounding at the same time (shown in red). The tenor voice sings G♯ while the bass sings G♮ momentarily beneath it, producing the clash of an augmented unison.

In this instance, the false relation is less pronounced: the contradicting E♭ (soprano voice) and E♮ (bass voice) (diminished octave) do not sound simultaneously. Here the false relation occurs because the top voice is descending in a minor key, and therefore takes the notes of the natural minor scale descending (the diatonic sixth degree). The bass voice ascends and therefore makes use of the ascending melodic minor scale (the raised sixth degree).

False relation is in this case desirable since this chromatic alteration follows a melodic idea, the rising 'melodic minor'. In such cases false relations must occur between different voices, as it follows that they cannot be produced by the semitones that occur diatonically in a mode or scale of any kind. This horizontal approach to polyphonic writing reflects the practices of composers in the Renaissance and Tudor periods, particularly in vocal composition, but it is also seen, for example, in the hexachord fantasies of William Byrd (for keyboard). Indeed, vocal music from this era does not often have these accidentals notated in the manuscript (see Musica ficta);[3] experienced singers would have decided whether or not they were appropriate in a given musical context.

Many composers from the late 16th century onwards however began using the effect deliberately as an expressive device in their word setting. This practice continued well into the Romantic era, and can be heard in the music of Mozart and Chopin, for example.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Dyson, George (2001). "False relation". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Arnold Whittall (2002). "False Relation", The Oxford Companion to Music. Ed. Alison Latham. Oxford University Press. King's College London. Oxford Reference Online. Accessed 18 March 2007.

- ^ Bent, Margaret (2001). "Musica ficta, §1: Introduction". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

External links

[edit]- Luís Henriques (Saturday, July 21, 2007). "William Byrd - Ave Verum Corpus", Atrium Musicologicum. Another description of the use of false relation in Byrd's Ave Verum Corpus. [This blog is open to invited readers only]

- Early Music Sources (Elam Rotem): False relations in the late Renaissance on YouTube