Rhea (moon): Difference between revisions

Kwamikagami (talk | contribs) pronunciation |

|||

| (814 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Moon of Saturn}} |

|||

{| border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="2" align="right" |

|||

{{Distinguish|text=the asteroid named [[577 Rhea]]}} |

|||

|+ '''Rhea''' |

|||

{{Infobox planet |

|||

|- |

|||

| name = Rhea |

|||

| colspan="2" bgcolor="#080000" align="center" | [[Image:Rhea (moon) thumb.jpg|Rhea, taken by Voyager 1 (NASA)]] |

|||

| mpc_name = Saturn V |

|||

|- |

|||

| pronounced = {{IPAc-en|ˈ|r|iː|.|ə}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Consulmagno |first1=G. |last2=Ryche |first2=H. |date=Feb 9, 1982 |title=Pronouncing the names of the moons of Saturn |url=https://www.vaticanobservatory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Consolmagno-Reiche-Pronouncing-Moons-of-Saturn.pdf |journal=EOS |volume=63 |issue=6 |pages=146–147 |doi=10.1029/EO063i006p00146 |access-date=Nov 30, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

! bgcolor="#a0ffa0" colspan="2" | Discovery |

|||

| named_after = [[Rhea (mythology)|Ῥέᾱ]] ''Rheā'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| adjectives = Rhean {{IPAc-en|ˈ|r|iː|.|ən}}<ref>Moore et al. (1984) "The Geomorphology of Rhea", ''Proceedings of the fifteenth Lunar and Planetary Science'', Part 2, p C-791–C-794</ref> |

|||

! align="left" | Discovered by |

|||

| image = PIA07763 Rhea full globe5.jpg |

|||

| [[Giovanni Cassini]] |

|||

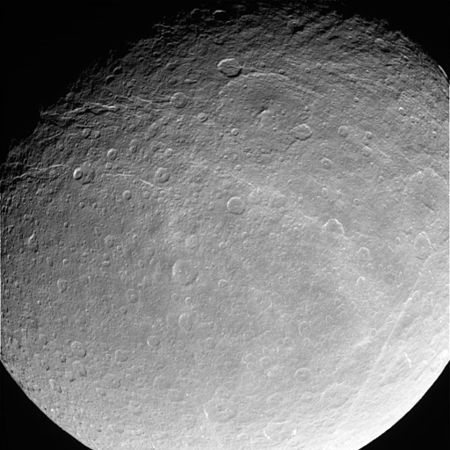

| caption = Mosaic of Rhea, assembled from ''[[Cassini–Huygens|Cassini]]'' imagery taken on 26 November 2005 |

|||

|- |

|||

| discoverer = [[Giovanni Domenico Cassini|G. D. Cassini]]<ref name=space.com.Rhea/> |

|||

! align="left" | Discovered in |

|||

| discovered = December 23, 1672<ref name=space.com.Rhea>{{cite web |url=http://www.space.com/20577-rhea-saturn-s-dirty-snowball-moon.html |title=Rhea: Saturn's dirty snowball moon |last=Tillman |first=Nola Taylor |date=2016-06-29 |website=space.com}}</ref> |

|||

| [[1672]] |

|||

| orbit_ref = <ref name="NSES" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| semimajor = {{val|527040|u=km}}<ref name="NSSDC"/> |

|||

! bgcolor="#a0ffa0" colspan="2" | [[Orbit]]al characteristics |

|||

| eccentricity = {{val|0.001}}<ref name="NSSDC"/> |

|||

|- |

|||

| period = {{val|4.518212|u=[[Day|d]]}} |

|||

! align="left" | [[Semimajor axis]] |

|||

| avg_speed = 8.48 km/s{{efn|name=calculated|Calculated on the basis of other parameters.}} |

|||

| 527,040 [[kilometer|km]] |

|||

| inclination = 0.35°<ref name="NSSDC"/> |

|||

|- |

|||

| satellite_of = [[Saturn]] |

|||

| mean_radius = {{val|763.5|0.5|u=km}}<ref name="Jacobson2022">{{cite Q|Q126389785|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

| 0.001 |

|||

| dimensions = 1532.4 × 1525.6 × 1524.4 km <ref name="Roatsch et al. 2009" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| surface_area = {{val|7325342|u=km<sup>2</sup>}}{{efn|name=surface_area}} |

|||

! align="left" | Revolution period |

|||

| mass = {{val|2.3064854|0.0000522|e=21|u=kg}}<ref name="Jacobson2022"/> (~3.9{{e|-4}} Earths) |

|||

| 108 h 25 min 12 s |

|||

| density = {{val|1.2372|0.0029|u=g/cm<sup>3</sup>}}<ref name="Jacobson2022"/> |

|||

|- |

|||

| surface_grav = {{Gr|2.306|763.8|2}} [[Acceleration|m/s<sup>2</sup>]]{{efn|Surface area derived from the radius (''r''): {{math|4\pi r^2}}.}} |

|||

! align="left" | [[Inclination]] |

|||

| moment_of_inertia_factor = {{val|0.3911|0.0045}}<ref name="Anderson2007">{{cite journal |last1= Anderson|first1=J. D.|last2= Schubert|first2= G.|title= Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice|journal= Geophysical Research Letters |volume= 34|issue= 2|pages=L02202|year= 2007|doi= 10.1029/2006GL028100|bibcode= 2007GeoRL..34.2202A|doi-access= free}}</ref> (disputed/unclear<ref name="Anderson2008" />) |

|||

| 0.35 ° |

|||

| escape_velocity = {{V2|2.306|763.8|3}} km/s |

|||

|- |

|||

| rotation = {{val|4.518212|u=d}} <br /> ([[Synchronous rotation|synchronous]]) |

|||

! align="left" | Is a [[natural satellite|satellite]] of |

|||

| axial_tilt = zero |

|||

| [[Saturn (planet)|Saturn]] |

|||

| albedo = {{val|0.949|0.003}} ([[geometric albedo|geometric]]) <ref name="Verbiscer et al. 2007" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

| magnitude = 10 <ref name="Observatorio ARVAL" /> |

|||

! bgcolor="#a0ffa0" colspan="2" | Physical characteristics |

|||

| temp_name1 = [[Kelvin]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| min_temp_1 = 53 [[Kelvin|K]] |

|||

! align="left" | Mean [[diameter]] |

|||

| mean_temp_1 = |

|||

| 1528 km |

|||

| max_temp_1 = 99 K |

|||

|- |

|||

}} |

|||

! align="left" | Surface [[area]] |

|||

| 7,300,000 [[square kilometer|km<sup>2</sup>]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | [[Mass]] |

|||

| 2.3166×10<sup>21</sup> [[kilogram|kg]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | Mean [[density]] |

|||

| 1.24 g/cm<sup>3</sup> |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | Surface [[gravity]] |

|||

| 0.26 [[Acceleration|m/s<sup>2</sup>]] |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | Rotation period |

|||

| 108 h 25 min 12 s<br>([[Synchronous rotation|synchronous]]) |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | [[Axial tilt]] |

|||

| 0.029 ° |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | [[Albedo]] |

|||

| 0.65 |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | Surface [[Temperature|temp.]] |

|||

| |

|||

{| cellspacing="0" cellpadding="2" border="0" |

|||

|- |

|||

! min !! mean !! max |

|||

|- |

|||

| 53 [[Kelvin|K]] |

|||

| || 99 K |

|||

|} |

|||

|- |

|||

! align="left" | [[celestial body's atmosphere|Atmosphere]] |

|||

| none |

|||

|} |

|||

'''Rhea''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|r|iː|.|ə}}) is the second-largest [[natural satellite|moon]] of [[Saturn]] and the [[List of natural satellites by diameter|ninth-largest moon]] in the [[Solar System]], with a surface area that is comparable to the area of [[Australia]]. It is the smallest body in the [[Solar System]] for which precise measurements have confirmed a shape consistent with [[hydrostatic equilibrium]]. Rhea has a nearly circular orbit around Saturn, but it is also [[Tidal locking|tidally locked]], like Saturn's other major moons; that is, it [[Rotation|rotates]] with the same period it revolves ([[orbit]]s), so one hemisphere always faces towards the planet. |

|||

'''Rhea''' ("REE uh") is the second largest [[natural satellite|moon]] of [[Saturn (planet)|Saturn]] and was discovered in [[1672]] by [[Giovanni Cassini]]. It is named after the [[titan (mythology)|titan]] [[Rhea (mythology)|Rhea]] of [[Greek mythology]]. It is also designated Saturn V. |

|||

The moon itself has a fairly low density, composed of roughly three-quarters ice and only one-quarter rock. The surface of Rhea is heavily cratered, with distinct leading and trailing hemispheres. Like the moon [[Dione (moon)|Dione]], it has high-[[albedo]] ice cliffs that appear as bright wispy streaks visible from space. The surface temperature varies between −174 °C and −220 °C. |

|||

The name "Rhea" and the names of all seven satellites of Saturn then known were suggested by [[John Herschel]] in his [[1847]] publication ''Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope''. [http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/MNRAS/0008//0000042.000.html] |

|||

Rhea was discovered in 1672 by [[Giovanni Domenico Cassini]]. Since then, it has been visited by both [[Voyager program|Voyager probes]] and was the subject of close targeted [[flyby (spaceflight)|flyby]]s by the [[Cassini–Huygens|''Cassini'']] orbiter in 2005, 2007, 2010, 2011, and once more in 2013. |

|||

==Physical characteristics== |

|||

Rhea is an icy body with a density of about 1,240 kg/m<sup>3</sup>. This low density indicates that it has a rocky core taking up less than one-third of the moon's mass with the rest composed of water-ice. Rhea's features resemble those of [[Dione (moon)|Dione]], with dissimilar leading and trailing hemispheres, suggesting similar composition and histories. The temperature on Rhea is −174 °C in direct sunlight and between −200 °C and −220 °C in the shade. |

|||

== Discovery == |

|||

Rhea is heavily cratered and has bright wispy markings on its surface. |

|||

Rhea was discovered by [[Giovanni Domenico Cassini]] on 23 December 1672, with a {{Convert|10.4|m|ft|adj=on}} telescope made by [[Giuseppe Campani]].<ref name=space.com.Rhea/><ref>{{Cite Q|Q126386131}}</ref> Cassini named the four moons he discovered (Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and [[Iapetus (moon)|Iapetus]]) ''[[Sidera Lodoicea]]'' (the stars of Louis) to honor King [[Louis XIV of France|Louis XIV]].<ref name="space.com.Rhea" /> Rhea was the second [[moons of Saturn|moon of Saturn]] that Cassini discovered, and the third moon discovered around Saturn overall.<ref name=space.com.Rhea/> |

|||

Its surface can be divided into two geologically different areas based on [[crater]] density; the first area contains craters which are larger than 40 km in diameter, whereas the second area, in parts of the polar and equatorial regions, has craters under 40 km in diameter. This suggests that a major resurfacing event occurred some time during its formation. |

|||

==Name== |

|||

The leading hemisphere is heavily cratered and uniformly bright. |

|||

Rhea is named after the [[titan (mythology)|Titan]] [[Rhea (mythology)|Rhea]] of [[Greek mythology]], the "mother of the gods" and wife of [[Cronus|Kronos]], the [[Interpretatio graeca|Greek counterpart]] of the god [[Saturn (mythology)|Saturn]]. It is also designated '''Saturn V''' (being the fifth major moon going outward from the planet, after [[Mimas (moon)|Mimas]], [[Enceladus (moon)|Enceladus]], [[Tethys (moon)|Tethys]], and [[Dione (moon)|Dione]]).<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/saturn-moons/rhea/in-depth/|title=In Depth {{!}} Rhea|date=December 19, 2019|website=NASA Solar System Exploration|publisher=NASA Science|access-date=January 7, 2020}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/Planets|title=Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers|date=July 21, 2006|work=Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature|publisher=USGS Astrogeology|access-date=January 7, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

As on [[Callisto (moon)| Callisto]], the craters lack the high relief features seen on the [[Moon]] and [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]]. |

|||

On the trailing hemisphere there is a network of bright swaths on a dark background and few visible craters. It is thought that these bright swaths may be material ejected from ice [[volcano]]es early in Rhea's history when it was still liquid inside. |

|||

Astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and [[Titan (moon)|Titan]] as ''Saturn I'' through ''Saturn V''.<ref name=space.com.Rhea/> Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered, in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to ''Saturn VII'', and then to ''Saturn VIII'' with the discovery of [[Hyperion (moon)|Hyperion]] in 1848.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

'''See also:''' [[List of geological features on Rhea]] |

|||

Rhea was not named until 1847, when [[John Herschel]] (son of [[William Herschel]], discoverer of the planet [[Uranus]] and two other moons of Saturn, [[Mimas (moon)|Mimas]] and [[Enceladus]]) suggested in ''Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope'' that the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Kronos (Saturn, in Roman mythology), be used.<ref name="Lassell1848" /><ref name=space.com.Rhea/> |

|||

The [[Cassini-Huygens]] orbiter is due to perform a flyby of Rhea on [[November 25]], [[2005]]. |

|||

<br clear="all"> |

|||

== Orbit == |

|||

<center>''... | [[Dione (moon)|Dione]], [[Helene (moon)|Helene]] | '''Rhea''' | [[Titan (moon)|Titan]] | ...''</center> |

|||

The orbit of Rhea has very low [[Orbital eccentricity|eccentricity]] (0.001), meaning it is nearly circular. It has a low [[Orbital inclination|inclination]] of less than a degree, inclined by only 0.35° from Saturn's equatorial plane.<ref name="NSSDC"/> |

|||

{{Saturn_Footer}} |

|||

[[Category:Saturn's moons]] |

|||

Rhea is [[Tidal locking|tidally locked]] and rotates synchronously; that is, it [[Rotation|rotates]] at the same speed it revolves (orbits), so one hemisphere is always facing towards Saturn. This is called the [[near pole]]. Equally, one hemisphere always faces forward, relative to the direction of movement; this is called the [[leading hemisphere]]; the other side is the trailing hemisphere, which faces backwards relative to the moon's motion.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Rhea {{!}} 2nd Largest Moon of Saturn {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Rhea-astronomy |access-date=2024-06-13 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Terms and Definitions |url=http://astro.if.ufrgs.br/solar/terms.htm |access-date=2024-06-13 |website=astro.if.ufrgs.br}}</ref> |

|||

[[de:Rhea (Mond)]] |

|||

[[es:Rhea (luna)]] |

|||

== Physical characteristics == |

|||

[[fr:Rhéa (lune)]] |

|||

[[nl:Rhea (maan)]] |

|||

=== Size, mass, and internal structure === |

|||

[[zh:土卫五]] |

|||

[[File:Rhea, Earth & Moon size comparison.jpg|left|thumb|250x250px|Size comparison of [[Earth]] (right), the [[Moon]] (left top), and Rhea (left down)]] |

|||

Rhea is an icy body with a [[density]] of about 1.236 g/cm<sup>3</sup>. This low density indicates that it is made of ~25% rock (density ~3.25 g/cm<sup>3</sup>) and ~75% water ice (density ~0.93 g/cm<sup>3</sup>). A layer of [[Ice II]] (a high-pressure and extra-low temperature form of ice) is believed, based on the moon's temperature profile, to start around {{Convert|350 to 450|km|mi}} beneath the surface.<ref>{{Cite Q|Q126417371}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Rg6dBAAAQBAJ&dq=%22surface+gravity%22+of+%22rhea%22&pg=RA4-PA628 |title=Treatise on Geophysics |date=2015-04-17 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-444-53803-1 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Hobbs |first=Peter Victor |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7Is6AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA61 |title=Ice Physics |date=2010-05-06 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-958771-1 |language=en}}</ref> Rhea is {{Convert|1528|km|mi}} in diameter, but is still only a third of the size of [[Titan (moon)|Titan]], Saturn's biggest moon.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Rhea - NASA Science |url=https://science.nasa.gov/saturn/moons/rhea/ |access-date=2024-06-07 |website=science.nasa.gov |language=en-US}}</ref> Although Rhea is the ninth-largest moon, it is only the tenth-most massive moon. Indeed, [[Oberon (moon)|Oberon]], the second-largest moon of Uranus, has almost the same size, but is significantly denser than Rhea (1.63 vs 1.24) and thus more massive, although Rhea is slightly larger by volume.<ref group="lower-alpha">The moons more massive than Rhea are: the [[Moon]], the four [[Galilean moons]], Titan, Triton, Titania, and Oberon. Oberon, Uranus's second-largest moon, has a radius that is ~0.4% smaller than Rhea's, but a density that is ~26% greater. See [http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par JPLSSD.]</ref> The surface area of the moon can be estimated at {{Convert|7330000|km2|mi2|sigfig=3|round=10}}, similar to Australia (7,688,287 km<sup>2</sup>).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Australia |first=Geoscience |date=2014-06-27 |title=Area of Australia - States and Territories |url=https://www.ga.gov.au/scientific-topics/national-location-information/dimensions/area-of-australia-states-and-territories |access-date=2024-06-07 |website=Geoscience Australia |language=en}}</ref>{{Efn|The [[surface area]] can be estimated, given the radius, with the formula {{math|4''πr''<sup>2</sup>}}|name=surface_area}} |

|||

Before the ''[[Cassini–Huygens]]'' mission, it was assumed that Rhea had a rocky core.<ref name="Anderson2003" /> However, measurements taken during a close flyby by the [[Cassini–Huygens|''Cassini'']] orbiter in 2005 cast this into doubt. In a paper published in 2007 it was claimed that the axial dimensionless [[moment of inertia]] coefficient was 0.4.{{refn | group = lower-alpha | More precisely, 0.3911.<ref name="Anderson_2007" /> }}<ref name="Anderson_2007" /> Such a value indicated that Rhea had an almost homogeneous interior (with some compression of ice in the center) while the existence of a rocky core would imply a moment of inertia of about 0.34.<ref name="Anderson2003" /> In the same year another paper claimed the moment of inertia was about 0.37.{{refn | group = lower-alpha | More precisely, 0.3721.<ref name="Iess2007" /> }} Rhea being either partially or fully differentiated would be consistent with the observations of the ''Cassini'' probe.<ref name="Iess2007" /> A year later yet another paper claimed that the moon may not be in [[hydrostatic equilibrium]], meaning that the moment of inertia cannot be determined from the gravity data alone.<ref name="MacKenzie2008" /> In 2008 an author of the first paper tried to reconcile these three disparate results. He concluded that there is a systematic error in the ''Cassini'' radio Doppler data used in the analysis, but after restricting the analysis to a subset of data obtained closest to the moon, he arrived at his old result that Rhea was in hydrostatic equilibrium and had a moment of inertia of about 0.4, again implying a homogeneous interior.<ref name="Anderson2008" /> |

|||

The [[Triaxial ellipsoid|triaxial]] shape of Rhea is consistent with a homogeneous body in [[hydrostatic equilibrium]] rotating at Rhea's angular velocity.<ref name="Thomas2007" /> Modelling in 2006 suggested that Rhea could be barely capable of sustaining an [[subsurface ocean|internal liquid-water ocean]] through heating by [[radioactive decay]]; such an ocean would have to be at about 176 K, the [[eutectic temperature]] for the water–ammonia system.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal| doi = 10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005| last1 = Hussmann| first1 = Hauke| last2 = Sohl| first2 = Frank| last3 = Spohn| first3 = Tilman| date = November 2006| title = Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects| journal = [[Icarus (journal)|Icarus]]| volume = 185| issue = 1| pages = 258–273| url = https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225019299| bibcode = 2006Icar..185..258H| ref = {{sfnRef|Hussmann Sohl et al.|2006}}}}</ref> More recent indications are that Rhea has a homogeneous interior and hence that this ocean does not exist.<ref name=Anderson2008/> |

|||

=== Surface features === |

|||

{{main|List of geological features on Rhea}} |

|||

Rhea's features resemble those of [[Dione (moon)|Dione]], with distinct and dissmillar leading and trailing hemispheres, suggesting similar composition and histories. The temperature on Rhea is 99 K (−174 °C) in direct sunlight and between 73 K (−200 °C) and 53 K (−220 °C) in the shade. |

|||

[[File:PIA18310-SaturnMoon-Rhea-20150210.jpg|thumb|Surface features on Rhea well defined due to the lighting]] |

|||

Rhea has a rather typical heavily [[Impact crater|cratered]] surface,<ref name="MooreSchenk_2004" /> with the exceptions of a few large Dione-type chasmata or fractures (formerly known as [[Dione (moon)#Ice cliffs (formerly 'wispy terrain')|wispy terrain]]) on the trailing hemisphere (the side facing away from the direction of motion along Rhea's orbit)<ref name="Wagner2008" /> and a very faint "line" of material at Rhea's equator that may have been deposited by material deorbiting from its rings.<ref name="Schenk2009" /> Rhea has two very large impact basins on its hemisphere facing away from Saturn, which are about 400 and 500 km across.<ref name="Wagner2008" /> The more northerly and less degraded of the two, called [[Tirawa (crater)|Tirawa]], is roughly comparable in size to the basin Odysseus on [[Tethys (moon)|Tethys]].<ref name="MooreSchenk_2004" /> There is a 48 km-diameter impact crater at 112°W that is prominent because of an extended system of bright [[ray system|ray]]s, which extend up to {{Convert|400|km|mi|abbr=on}} away from the crater, across most of one hemisphere.<ref name="Wagner2008" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Schenk |first1=Paul |last2=Kirchoff |first2=Michelle |last3=Hoogenboom |first3=Trudi |last4=Rivera-Valentín |first4=Edgard |date=2020 |title=The anatomy of fresh complex craters on the mid-sized icy moons of Saturn and self-secondary cratering at the rayed crater Inktomi (Rhea) |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/maps.13592 |journal=Meteoritics & Planetary Science |language=en |volume=55 |issue=11 |pages=2440–2460 |doi=10.1111/maps.13592 |bibcode=2020M&PS...55.2440S |issn=1086-9379}}</ref> This crater, called [[Inktomi (crater)|Inktomi]], is nicknamed "The Splat", and may be one of the youngest craters on the inner moons of Saturn. This was hypothesized in a 2007 paper published by [[Lunar and Planetary Science Conference|''Lunar and Planetary Science'']].<ref name="Wagner2008" /> Rhea's [[impact crater]]s are more crisply defined than the flatter craters that are pervasive on [[Ganymede (moon)|Ganymede]] and [[Callisto (moon)|Callisto]]; it is theorized that this is due to a much lower [[surface gravity]] (0.26 [[Metre per second squared|m/s<sup>2</sup>]], compared to Ganymede's 1.428 m/s<sup>2</sup> and Callisto's 1.235 m/s<sup>2</sup>) and a stiffer crust of ice. Similarly, [[ejecta blanket]]s – asymmetrical blankets of ejected particles surrounding impact craters – are not present on Rhea, potentially another result of the moon's low surface gravity.<ref>{{Cite Q|Q126417214}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Rhea at approximately 2,348 miles (3,778 kilometers) away.jpg|thumb|Closeup showing two craters on Rhea's surface taken in 2013 by [[Cassini–Huygens|''Cassini'' spacecraft]]]] |

|||

Its surface can be divided into two geologically different areas based on [[impact crater|crater]] density; the first area contains craters which are larger than 40 km in diameter, whereas the second area, in parts of the polar and equatorial regions, has only craters under that size. This suggests that a major resurfacing event occurred some time during its formation. The leading hemisphere is heavily cratered and uniformly bright. As on [[Callisto (moon)|Callisto]], the craters lack the high relief features seen on the [[Moon]] and [[Mercury (planet)|Mercury]]. It has been theorized that these cratered plains are up to four billion years old on average.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/rhea|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160214000303/http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/rhea|url-status=dead|archive-date=2016-02-14|title=Rhea – Overview {{!}} Planets – NASA Solar System Exploration|website=NASA Solar System Exploration|access-date=2017-09-21}}</ref> On the trailing hemisphere there is a network of bright swaths on a dark background, and fewer craters.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Anderson |first1=J. D. |last2=Schubert |first2=G. |date=18 January 2007 |title=Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice |url=https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2006GL028100 |journal=Geophysical Research Letters |language=en |volume=34 |issue=2 |doi=10.1029/2006GL028100 |bibcode=2007GeoRL..34.2202A |issn=0094-8276}}</ref> It is believed, based on data from the Cassini probe, that these are tectonic features: depressions ([[graben]]) and troughs, with ice-covered cliff sides causing the lines' whiteness (more technically their [[albedo]]).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Wagner |first1=R. J. |last2=Giese |first2=B. |last3=Roatsch |first3=T. |last4=Neukum |first4=G. |last5=Denk |first5=T. |last6=Wolf |first6=U. |last7=Porco |first7=C. C. |date=May 2010 |title=Tectonic features on Rhea's trailing hemisphere: a first look at the Cassini ISS camera data from orbit 121, Nov. 21, 2009 |url=https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2010EGUGA..12.6731W |journal=EGU General Assembly 2010 |pages=6731|bibcode=2010EGUGA..12.6731W }}</ref> The extensive dark areas are thought to be deposited [[tholin]]s, which are a mix of complex [[organic compound]]s generated on the ice by [[pyrolysis]] and [[radiolysis]] of simple compounds containing carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen.<ref name='Cruikshank 2005'>[http://astrochemistry.org/docs/Cruikshanketal2005.pdf A spectroscopic study of the surfaces of Saturn's large satellites: H2O ice, tholins, and minor constituents] (PDF). Dale P. Cruikshank, Tobias Owen, [[Cristina Dalle Ore]], Thomas R. Geballe, Ted L. Roush, Catherine de Bergh, Scott A. Sandford, Francois Poulet, Gretchen K. Benedix, Joshua P. Emery. ''Icarus'', 175, pages: 268–283, 2 March 2005.</ref> The trailing side of Rhea's surface is [[Magnetosphere of Saturn#Sources and transport of plasma|irradiated by Saturn's magnetosphere]], which may cause chemical-level changes on the surface, including [[radiolysis]] (see {{Section link|2=Atmosphere|nopage=y}}). Particles from Saturn's [[E Ring (ring of Saturn)|E-ring]] are also flung onto the moon's leading hemisphere, coating it.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

Rhea has some evidence of endogenic activity – that is, activity originating from within the moon, such as heating and [[Cryovolcano|cryovolcanic]] activity: there are [[Fault (geology)|fault]] systems and craters with uplifted bases (so-called "relaxed" craters), although the latter is apparently only present in large craters more than {{Convert|100|km|mi|abbr=on}} across.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Aponte-Hernández |first1=Betzaida |last2=Rivera-Valentín |first2=Edgard G. |last3=Kirchoff |first3=Michelle R. |last4=Schenk |first4=Paul M. |date=Dec 2012 |title=Morphometric Study of Craters on Saturn's Moon Rhea |journal=The Planetary Science Journal |volume=2 |issue=6 |pages=235 |doi=10.3847/psj/ac32d4 |issn=2632-3338 |pmc=8670330 |pmid=34913034 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=White |first1=Oliver L. |last2=Schenk |first2=Paul M. |last3=Bellagamba |first3=Anthony W. |last4=Grimm |first4=Ashley M. |last5=Dombard |first5=Andrew J. |last6=Bray |first6=Veronica J. |date=2017-05-15 |title=Impact crater relaxation on Dione and Tethys and relation to past heat flow |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103516305048 |journal=Icarus |volume=288 |pages=37–52 |doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2017.01.025 |bibcode=2017Icar..288...37W |issn=0019-1035}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Elowitz |first1=Mark |last2=Sivaraman |first2=Bhalamurugan |last3=Hendrix |first3=Amanda |last4=Lo |first4=Jen-Iu |last5=Chou |first5=Sheng-Lung |last6=Cheng |first6=Bing-Ming |last7=Sekhar |first7=B. N. Raja |last8=Mason |first8=Nigel J. |date=2021-01-22 |title=Possible detection of hydrazine on Saturn's moon Rhea |journal=Science Advances |language=en |volume=7 |issue=4 |doi=10.1126/sciadv.aba5749 |issn=2375-2548 |pmc=10670839 |pmid=33523937|bibcode=2021SciA....7.5749E }}</ref> |

|||

==Formation== |

|||

The moons of Saturn are thought to have formed through [[Accretion disc|co-accretion]], a similar process to that believed to have formed the planets in the Solar System. As the young giant planets formed, they were surrounded by discs of material that gradually coalesced into moons. However, a model proposed by [[Erik Ian Asphaug|Erik Asphaug]] and [[Andreas Reufer]] for the formation of [[Titan (moon)|Titan]] may also shine a new light on the origin of Rhea and [[Iapetus (moon)|Iapetus]]. In this model, Titan was formed in a series of [[giant impact]]s between pre-existing moons, and Rhea and Iapetus are thought to have formed from part of the debris of these collisions.<ref>{{cite web |title=Giant impact scenario may explain the unusual moons of Saturn |work=Space Daily |date=2012 |url=http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Giant_impact_scenario_may_explain_the_unusual_moons_of_Saturn_999.html |access-date=2012-10-19 }}</ref><gallery class="center" widths="100" heights="300" mode="packed"> |

|||

File:Rhea ice cliffs.jpg|Image of the wispy hemisphere, showing ice cliffs – Powehiwehi (upper center); chasmata stretch from upper left to right center – Onokoro Catenae (lower right) |

|||

File:PIA08148 (Rhea-Splat).jpg|View of Rhea's leading hemisphere with crater Inktomi and its prominent [[ray system]] just below center; [[impact basin]] [[Tirawa (crater)|Tirawa]] is at upper left |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Atmosphere == |

|||

On November 27, 2010, [[NASA]] announced the discovery of an extremely tenuous atmosphere—an [[exosphere]]. It consists of oxygen and carbon dioxide in proportion of roughly 5 to 2. The surface density of the exosphere is from 10<sup>5</sup> to 10<sup>6</sup> molecules in a cubic centimeter, depending on local temperature. The main source of oxygen is [[radiolysis]] of water ice at the surface via irradiation from the [[magnetosphere of Saturn]]. The source of the carbon dioxide is less clear, but it may be related to [[oxidation]] of the organics present in ice or to [[outgassing]] of the moon's interior.<ref name=":1" /><ref name="atmosphere" /><ref name="Teolis2010" /> |

|||

== Possible ring system == |

|||

{{main|Rings of Rhea}} |

|||

On March 6, 2008, [[NASA]] announced that Rhea may have a weak ring system. This would mark the first discovery of rings around a moon. The rings' existence was inferred by observed changes in the flow of electrons trapped by Saturn's magnetic field as ''Cassini'' passed by Rhea.<ref name="rings" /><ref name="Jones2008" /><ref name="LakdawallaE" /> Dust and debris could extend out to Rhea's [[Hill sphere]], but were thought to be denser nearer the moon, with three narrow rings of higher density. The case for a ring was strengthened by the subsequent finding of the presence of a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed along Rhea's equator (interpreted as the impact points of deorbiting ring material).<ref name="Lakdawalla2" /> However, when ''Cassini'' made targeted observations of the putative ring plane from several angles, there was no evidence of ring material found, suggesting that another explanation for the earlier observations is needed.<ref name="Tiscareno2010" /><ref name="norings" /> |

|||

== Exploration == |

|||

The first images of Rhea were obtained by ''[[Voyager program|Voyager 1 & 2]]'' spacecraft in 1980–1981. |

|||

There were five close targeted fly-bys by the ''[[Cassini–Huygens|Cassini]]'' orbiter, which was one part of the dual orbiter and lander ''Cassini–Huygens'' mission. Launched in 1997, ''Cassini–Huygens'' was targeted at the Saturn system; in total it took more than 450 thousand images.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Cassini |url=https://science.nasa.gov/mission/cassini/quick-facts/ |access-date=2024-06-20 |website=science.nasa.gov |language=en-US}}</ref> ''Cassini'' passed Rhea at a distance of 500 km on November 26, 2005; at a distance of 5,750 km on August 30, 2007; at a distance of 100 km on March 2, 2010; at 69 km flyby on January 11, 2011;<ref name="CookJ2011" /> and a last flyby at 992 km on March 9, 2013.<ref name="LastFlybyRhea" /> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Planet#Objects formerly considered planets|Former classification of planets]] |

|||

* [[List of natural satellites]] |

|||

* [[Saturn's moons in fiction#Rhea|Rhea in fiction]] |

|||

* [[Rings of Rhea]] |

|||

* [[Subsatellite]] |

|||

* [[Moons of Saturn]] |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

{{Reflist |

|||

| colwidth = 30em |

|||

| group = lower-alpha |

|||

}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{Reflist |

|||

| colwidth = 30em |

|||

| refs = |

|||

<ref name="NSSDC"> |

|||

{{Cite web|website=[[National Space Science Data Center]]|url=https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/saturniansatfact.html|title=Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20240210110147/https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/saturniansatfact.html|archive-date=10 Feb 2024}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="NSES"> |

|||

{{cite web|url=http://www.minorplanetcenter.org/iau/NatSats/NaturalSatellites.html|title=Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service|website=Minor Planet Center}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Roatsch et al. 2009"> |

|||

{{cite book| doi = 10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24| last1 = Roatsch| first1 = T.| last2 = Jaumann| first2 = R.| last3 = Stephan| first3 = K.| last4 = Thomas| first4 = P. C.| year = 2009| chapter = Cartographic Mapping of the Icy Satellites Using ISS and VIMS Data| title = Saturn from Cassini-Huygens| pages = 763–781| isbn = 978-1-4020-9216-9| ref = {{sfnRef|Roatsch Jaumann et al.|2009}}}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Verbiscer et al. 2007"> |

|||

{{cite journal| doi = 10.1126/science.1134681| last1 = Verbiscer| first1 = A.| last2 = French| first2 = R.| last3 = Showalter| first3 = M.| last4 = Helfenstein| first4 = P.| title = Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act| journal = Science| volume = 315| issue = 5813| page = 815| date = 9 February 2007| pmid = 17289992| bibcode = 2007Sci...315..815V| s2cid = 21932253| ref = {{sfnRef|Verbiscer French et al.|2007}}}} (supporting online material, table S1) |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Observatorio ARVAL"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| author = Observatorio ARVAL |

|||

| title = Classic Satellites of the Solar System |

|||

| publisher = Observatorio ARVAL |

|||

| date = April 15, 2007 |

|||

| url = http://www.oarval.org/ClasSaten.htm |

|||

| access-date = 2011-12-17 |

|||

| ref = {{sfnRef|Observatorio ARVAL}} |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Lassell1848"> |

|||

As reported by [[William Lassell]], [http://adsabs.harvard.edu//full/seri/MNRAS/0008//0000042.000.html Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43] (January 14, 1848) |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Anderson2003"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/S0031-9201(03)00035-9 |

|||

| last1 = Anderson |

|||

| first1 = J. D. |

|||

| last2 = Rappaport |

|||

| first2 = N. J. |

|||

| last3 = Giampieri |

|||

| first3 = G. |

|||

| display-authors = 3 |

|||

| last4 = Schubert |

|||

| first4 = Gerald |

|||

| last5 = Moore |

|||

| first5 = William B. |

|||

| date = 2003 |

|||

| title = Gravity field and interior structure of Rhea |

|||

| journal = [[Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors]] |

|||

| volume = 136 |

|||

| issue = 3–4 |

|||

| pages = 201–213 |

|||

| bibcode = 2003PEPI..136..201A |

|||

| citeseerx = 10.1.1.7.5250 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Anderson_2007"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| doi = 10.1029/2006GL028100 |

|||

| last1 = Anderson |

|||

| first1 = J. D. |

|||

| last2 = Schubert |

|||

| first2 = J. |

|||

| date = 2007 |

|||

| title = Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice |

|||

| journal = [[Geophysical Research Letters]] |

|||

| volume = 34 |

|||

| issue = 2 |

|||

| pages = L02202 |

|||

| doi-access = free |

|||

| bibcode = 2007GeoRL..34.2202A |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Iess2007"> |

|||

{{Cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.027 |last1=Iess |first1=L. |last2=Rappaport |first2=N. |last3=Tortora |first3=P. |last4=Lunine |first4=Jonathan I. |last5=Armstrong |first5=J. |last6=Asmar |first6=S. |last7=Somenzi |first7=L. |last8=Zingoni |first8=F. |title=Gravity field and interior of Rhea from Cassini data analysis |journal=Icarus |volume=190 |issue=2 |pages=585 |year=2007 |bibcode=2007Icar..190..585I }} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="MacKenzie2008"> |

|||

{{Cite journal | doi = 10.1029/2007GL032898 | last1 = MacKenzie | first1 = R. A. | last2 = Iess | first2 = L. | last3 = Tortora | first3 = P. | last4 = Rappaport | first4 = N. J. | title = A non-hydrostatic Rhea | journal = Geophysical Research Letters | volume = 35 | issue = 5 | pages = L05204 | year = 2008 | doi-access = free | bibcode = 2008GeoRL..35.5204M | hdl = 11573/17051 | hdl-access = free }} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Anderson2008"> |

|||

{{cite conference |

|||

| last = Anderson |

|||

| first = John D. |

|||

|date=July 2008 |

|||

| title = Rhea's Gravitational Field and Internal Structure |

|||

| conference = 37th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 13–20 July 2008, in Montréal, Canada |

|||

| page = 89 |

|||

| bibcode = 2008cosp...37...89A |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Thomas2007"> |

|||

{{cite journal| doi = 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012| last1 = Thomas| first1 = P. C.| last2 = Burns| first2 = J. A.| last3 = Helfenstein| first3 = P.| last4 = Squyres| first4 = S.| last5 = Veverka| first5 = J.| last6 = Porco| first6 = C.| last7 = Turtle| first7 = E. P.| last8 = McEwen| first8 = A.| last9 = Denk| first9 = T.|first10 = B. |last10 = Giesef|first11=T. |last11 = Roatschf|first12=T. V. |last12 = Johnsong|first13=R. A. |last13 = Jacobsong| date = October 2007| title = Shapes of the saturnian icy satellites and their significance| journal = Icarus| volume = 190| issue = 2| pages = 573–584| bibcode = 2007Icar..190..573T| url = http://www.geoinf.fu-berlin.de/publications/denk/2007/ThomasEtAl_SaturnMoonsShapes_Icarus_2007.pdf| access-date = 15 December 2011| ref = {{sfnRef|Thomas Burns et al.|2007}}}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="MooreSchenk_2004"> |

|||

{{cite journal| doi = 10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009| last1 = Moore| first1 = Jeffrey M.| last2 = Schenk| first2 = Paul M.| last3 = Bruesch| first3 = Lindsey S.| last4 = Asphaug| first4 = Erik| last5 = McKinnon| first5 = William B.| date=October 2004 | title = Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites| journal = Icarus| volume = 171| issue = 2| pages = 421–443| url = http://planets.oma.be/ISY/pdf/article_Icy.pdf| bibcode = 2004Icar..171..421M| ref = {{sfnRef|Moore Schenk et al.|2004}} |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Wagner2008"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Wagner |

|||

| first1 = R.J. |

|||

| last2 = Neukum |

|||

| first2 = G. |

|||

| display-authors = 2 |

|||

| last3 = Giese |

|||

| first3 = B. |

|||

| last4 = Roatsch |

|||

| first4 = T. |

|||

| last5 = Denk |

|||

| first5 = T. |

|||

| last6 = Wolf |

|||

| first6 = U. |

|||

| last7 = Porco |

|||

| first7 = C. C. |

|||

| date = 2008 |

|||

| title = Geology of Saturn's Satellite Rhea on the Basis of the High-Resolution Images from the Targeted Flyby 049 on Aug. 30, 2007 |

|||

| journal = Lunar and Planetary Science |

|||

| volume = XXXIX |

|||

| issue = 1391 |

|||

| page = 1930 |

|||

| bibcode = 2008LPI....39.1930W |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Schenk2009"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Schenk |

|||

| first1 = Paul M. |

|||

| last2 = McKinnon |

|||

| first2 = W. B. |

|||

| date = 2009 |

|||

| journal = American Astronomical Society |

|||

| title = Global Color Variations on Saturn's Icy Satellites, and New Evidence for Rhea's Ring |

|||

| volume = 41 |

|||

| pages = 3.03 |

|||

| bibcode = 2009DPS....41.0303S |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="atmosphere">{{cite web |

|||

| title = Cassini Finds Ethereal Atmosphere at Rhea |

|||

| publisher = NASA |

|||

| url = http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/whycassini/cassini20101126.html |

|||

| access-date = November 27, 2010 |

|||

| archive-date = September 16, 2011 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110916174510/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/whycassini/cassini20101126.html |

|||

| url-status = dead |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Teolis2010"> |

|||

{{Cite journal | last1 = Teolis | first1 = B. D. | last2 = Jones | first2 = G. H. | last3 = Miles | first3 = P. F. | last4 = Tokar | first4 = R. L. | last5 = Magee | first5 = B. A. | last6 = Waite | first6 = J. H. | last7 = Roussos | first7 = E. | last8 = Young | first8 = D. T. | last9 = Crary | first9 = F. J. | last10 = Coates | first10 = A. J. | last11 = Johnson | first11 = R. E. | last12 = Tseng | first12 = W. L. | last13 = Baragiola | first13 = R. A. | title = Cassini Finds an Oxygen–Carbon Dioxide Atmosphere at Saturn's Icy Moon Rhea | journal = Science| volume = 330 | issue = 6012| pages = 1813–1815| year = 2010 | pmid = 21109635 | doi = 10.1126/science.1198366|bibcode = 2010Sci...330.1813T | s2cid = 206530211 | doi-access = free }} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="rings">{{Cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/media/rhea20080306.html |

|||

|title=Saturn's Moon Rhea Also May Have Rings |

|||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20121022041030/http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/media/rhea20080306.html |

|||

|archivedate=2012-10-22 |

|||

|website=NASA |

|||

|date=June 3, 2006}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Jones2008"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Jones |

|||

| first1 = G. H. |

|||

| title = The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea |

|||

| journal = Science |

|||

| volume = 319 |

|||

| issue = 5868 |

|||

| pages = 1380–1384 |

|||

| date = 2008-03-07 |

|||

| doi = 10.1126/science.1151524 |

|||

| pmid = 18323452 |

|||

| bibcode = 2008Sci...319.1380J |

|||

| display-authors = 1 |

|||

| last2 = Roussos |

|||

| first2 = E. |

|||

| last3 = Krupp |

|||

| first3 = N. |

|||

| last4 = Beckmann |

|||

| first4 = U. |

|||

| last5 = Coates |

|||

| first5 = A. J. |

|||

| last6 = Crary |

|||

| first6 = F. |

|||

| last7 = Dandouras |

|||

| first7 = I. |

|||

| last8 = Dikarev |

|||

| first8 = V. |

|||

| last9 = Dougherty |

|||

| first9 = M. K. |

|||

| s2cid = 206509814 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="LakdawallaE"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|last=Lakdawalla |

|||

|first=E. |

|||

|title=A Ringed Moon of Saturn? ''Cassini'' Discovers Possible Rings at Rhea |

|||

|website=www.planetary.org |

|||

|publisher=[[Planetary Society]] |

|||

|date=2008-03-06 |

|||

|url=http://planetary.org/news/2008/0306_A_Ringed_Moon_of_Saturn_Cassini.html |

|||

|access-date=2008-03-09 |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080310165512/http://www.planetary.org/news/2008/0306_A_Ringed_Moon_of_Saturn_Cassini.html |

|||

|archive-date=2008-03-10 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Lakdawalla2">{{cite web |

|||

| last = Lakdawalla |

|||

| first = E. |

|||

| title = Another possible piece of evidence for a Rhea ring |

|||

| work = The Planetary Society Blog |

|||

| publisher = [[Planetary Society]] |

|||

| date = 5 October 2009 |

|||

| url = http://planetary.org/blog/article/00002137/ |

|||

| access-date = 2009-10-06 |

|||

| archive-date = 2012-02-17 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120217092805/http://planetary.org/blog/article/00002137/ |

|||

| url-status = dead |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="Tiscareno2010"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| doi = 10.1029/2010GL043663 |

|||

| author = Matthew S. Tiscareno |

|||

| author2 = Joseph A. Burns |

|||

| author3 = Jeffrey N. Cuzzi |

|||

| author4 = Matthew M. Hedman |

|||

| date = 2010 |

|||

| title = Cassini imaging search rules out rings around Rhea |

|||

| journal = [[Geophysical Research Letters]] |

|||

| volume = 37 |

|||

| issue = 14 |

|||

| pages = L14205 |

|||

| bibcode = 2010GeoRL..3714205T |

|||

| arxiv = 1008.1764 | s2cid = 59458559 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="norings"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|last=Kerr |

|||

|first=Richard A. |

|||

|date=2010-06-25 |

|||

|journal=[[Science (journal)|ScienceNow]] |

|||

|title=The Moon Rings That Never Were |

|||

|url=http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2010/06/the-moon-rings-that-never-were.html |

|||

|access-date=2010-08-05 |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100701090748/http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2010/06/the-moon-rings-that-never-were.html |

|||

|archive-date=2010-07-01 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="CookJ2011"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| last = Cook |

|||

| first = Jia-Rui C. |

|||

| date = 13 January 2011 |

|||

| title = Cassini Solstice Mission: Cassini Rocks Rhea Rendezvous |

|||

| work = saturn.jpl.nasa.gov |

|||

| publisher = NASA/JPL |

|||

| url = http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/cassinifeatures/feature20110113/ |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20110117034941/http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov/news/cassinifeatures/feature20110113/ |

|||

| url-status = dead |

|||

| archive-date = 17 January 2011 |

|||

| access-date = 11 December 2011 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

<ref name="LastFlybyRhea"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| title = NASA craft snaps last close-up photos of icy Saturn moon |

|||

| work = saturn.jpl.nasa.gov |

|||

| publisher = NASA/JPL |

|||

| url = http://science.nbcnews.com/_news/2013/03/16/17340546-nasa-craft-snaps-last-close-up-photos-of-icy-saturn-moon?lite |

|||

| access-date = 17 March 2013 |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Spoken Wikipedia|En-Rhea_(moon).ogg|date=2011-10-29}} |

|||

{{Commons category|Rhea (moon)|Rhea}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070801204714/http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/profile.cfm?Object=Sat_Rhea Rhea Profile] at [http://solarsystem.nasa.gov NASA's Solar System Exploration site] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20060831203603/http://www.planetary.org/explore/topics/saturn/rhea.html The Planetary Society: Rhea] |

|||

* [http://ciclops.org/search.php?x=20&y=7&search=Rhea ''Cassini'' images of Rhea] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110813151222/http://ciclops.org/search.php?x=20&y=7&search=Rhea |date=2011-08-13 }} |

|||

* [http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/target/Rhea Images of Rhea at JPL's Planetary Photojournal] |

|||

* Movie of [https://web.archive.org/web/20100601171509/http://sos.noaa.gov/videos/Rhea.mov Rhea's rotation] from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration site |

|||

* Rhea [http://www.ciclops.org/view/7313/Map_of_Rhea_-_March_2012 global] and [http://www.ciclops.org/view/7314/Rhea_Polar_Maps_-_March_2012 polar] basemaps (March 2012) from Cassini images |

|||

* [http://www.ciclops.org/view/6626/The_Rhea_Atlas Rhea altlas] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130424012008/http://www.ciclops.org/view/6626/The_Rhea_Atlas |date=2013-04-24 }} (released December 2010) from Cassini images |

|||

* [http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Page/RHEA/target Rhea nomenclature] and [http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/images/rhea_comp.pdf Rhea map with feature names] from the [http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov USGS planetary nomenclature page] |

|||

* [https://www.google.com/maps/space/rhea/@3.4035608,-102.4187081,6475987m/data=!3m1!1e3 Google Rhea 3D], interactive map of the moon |

|||

* [https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11834954 Saturn's moon Rhea has thin atmosphere] |

|||

* [https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/epdf/10.1098/rstl.1686.0013 An extract of the Journal Des Scavans. of April 22 ft. N. 1686. giving an account of two new satellites of Saturn, discovered lately by Mr. Cassini at the Royal Observatory at Paris] |

|||

{{Rhea|state=uncollapsed}} |

|||

{{Moons of Saturn}} |

|||

{{Solar System moons (compact)}} |

|||

{{Saturn}} |

|||

{{Atmospheres}} |

|||

{{Portal bar|Astronomy|Stars|Spaceflight|Outer space|Solar System}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Rhea (moon)| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Astronomical objects discovered in 1672|16721223]] |

|||

[[Category:Discoveries by Giovanni Domenico Cassini]] |

|||

[[Category:Moons of Saturn]] |

|||

[[Category:Moons with a prograde orbit]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:27, 26 October 2024

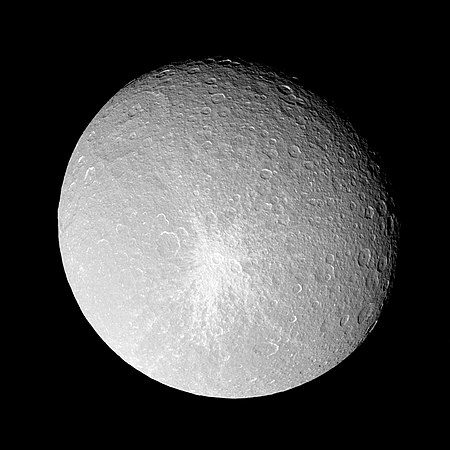

Mosaic of Rhea, assembled from Cassini imagery taken on 26 November 2005 | |||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | G. D. Cassini[1] | ||||||||

| Discovery date | December 23, 1672[1] | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

Designation | Saturn V | ||||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈriː.ə/[2] | ||||||||

Named after | Ῥέᾱ Rheā | ||||||||

| Adjectives | Rhean /ˈriː.ən/[3] | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics [4] | |||||||||

| 527040 km[5] | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.001[5] | ||||||||

| 4.518212 d | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 8.48 km/s[a] | ||||||||

| Inclination | 0.35°[5] | ||||||||

| Satellite of | Saturn | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| Dimensions | 1532.4 × 1525.6 × 1524.4 km [6] | ||||||||

| 763.5±0.5 km[7] | |||||||||

| 7325342 km2[b] | |||||||||

| Mass | (2.3064854±0.0000522)×1021 kg[7] (~3.9×10−4 Earths) | ||||||||

Mean density | 1.2372±0.0029 g/cm3[7] | ||||||||

| 0.26 m/s2[c] | |||||||||

| 0.3911±0.0045[8] (disputed/unclear[9]) | |||||||||

| 0.635 km/s | |||||||||

| 4.518212 d (synchronous) | |||||||||

| zero | |||||||||

| Albedo | 0.949±0.003 (geometric) [10] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| 10 [11] | |||||||||

Rhea (/ˈriː.ə/) is the second-largest moon of Saturn and the ninth-largest moon in the Solar System, with a surface area that is comparable to the area of Australia. It is the smallest body in the Solar System for which precise measurements have confirmed a shape consistent with hydrostatic equilibrium. Rhea has a nearly circular orbit around Saturn, but it is also tidally locked, like Saturn's other major moons; that is, it rotates with the same period it revolves (orbits), so one hemisphere always faces towards the planet.

The moon itself has a fairly low density, composed of roughly three-quarters ice and only one-quarter rock. The surface of Rhea is heavily cratered, with distinct leading and trailing hemispheres. Like the moon Dione, it has high-albedo ice cliffs that appear as bright wispy streaks visible from space. The surface temperature varies between −174 °C and −220 °C.

Rhea was discovered in 1672 by Giovanni Domenico Cassini. Since then, it has been visited by both Voyager probes and was the subject of close targeted flybys by the Cassini orbiter in 2005, 2007, 2010, 2011, and once more in 2013.

Discovery

[edit]Rhea was discovered by Giovanni Domenico Cassini on 23 December 1672, with a 10.4-metre (34 ft) telescope made by Giuseppe Campani.[1][12] Cassini named the four moons he discovered (Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Iapetus) Sidera Lodoicea (the stars of Louis) to honor King Louis XIV.[1] Rhea was the second moon of Saturn that Cassini discovered, and the third moon discovered around Saturn overall.[1]

Name

[edit]Rhea is named after the Titan Rhea of Greek mythology, the "mother of the gods" and wife of Kronos, the Greek counterpart of the god Saturn. It is also designated Saturn V (being the fifth major moon going outward from the planet, after Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, and Dione).[13][14]

Astronomers fell into the habit of referring to them and Titan as Saturn I through Saturn V.[1] Once Mimas and Enceladus were discovered, in 1789, the numbering scheme was extended to Saturn VII, and then to Saturn VIII with the discovery of Hyperion in 1848.[14]

Rhea was not named until 1847, when John Herschel (son of William Herschel, discoverer of the planet Uranus and two other moons of Saturn, Mimas and Enceladus) suggested in Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope that the names of the Titans, sisters and brothers of Kronos (Saturn, in Roman mythology), be used.[15][1]

Orbit

[edit]The orbit of Rhea has very low eccentricity (0.001), meaning it is nearly circular. It has a low inclination of less than a degree, inclined by only 0.35° from Saturn's equatorial plane.[5]

Rhea is tidally locked and rotates synchronously; that is, it rotates at the same speed it revolves (orbits), so one hemisphere is always facing towards Saturn. This is called the near pole. Equally, one hemisphere always faces forward, relative to the direction of movement; this is called the leading hemisphere; the other side is the trailing hemisphere, which faces backwards relative to the moon's motion.[16][17]

Physical characteristics

[edit]Size, mass, and internal structure

[edit]

Rhea is an icy body with a density of about 1.236 g/cm3. This low density indicates that it is made of ~25% rock (density ~3.25 g/cm3) and ~75% water ice (density ~0.93 g/cm3). A layer of Ice II (a high-pressure and extra-low temperature form of ice) is believed, based on the moon's temperature profile, to start around 350 to 450 kilometres (220 to 280 mi) beneath the surface.[18][19][20] Rhea is 1,528 kilometres (949 mi) in diameter, but is still only a third of the size of Titan, Saturn's biggest moon.[21] Although Rhea is the ninth-largest moon, it is only the tenth-most massive moon. Indeed, Oberon, the second-largest moon of Uranus, has almost the same size, but is significantly denser than Rhea (1.63 vs 1.24) and thus more massive, although Rhea is slightly larger by volume.[d] The surface area of the moon can be estimated at 7,330,000 square kilometres (2,830,000 sq mi), similar to Australia (7,688,287 km2).[22][b]

Before the Cassini–Huygens mission, it was assumed that Rhea had a rocky core.[23] However, measurements taken during a close flyby by the Cassini orbiter in 2005 cast this into doubt. In a paper published in 2007 it was claimed that the axial dimensionless moment of inertia coefficient was 0.4.[e][24] Such a value indicated that Rhea had an almost homogeneous interior (with some compression of ice in the center) while the existence of a rocky core would imply a moment of inertia of about 0.34.[23] In the same year another paper claimed the moment of inertia was about 0.37.[f] Rhea being either partially or fully differentiated would be consistent with the observations of the Cassini probe.[25] A year later yet another paper claimed that the moon may not be in hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning that the moment of inertia cannot be determined from the gravity data alone.[26] In 2008 an author of the first paper tried to reconcile these three disparate results. He concluded that there is a systematic error in the Cassini radio Doppler data used in the analysis, but after restricting the analysis to a subset of data obtained closest to the moon, he arrived at his old result that Rhea was in hydrostatic equilibrium and had a moment of inertia of about 0.4, again implying a homogeneous interior.[9]

The triaxial shape of Rhea is consistent with a homogeneous body in hydrostatic equilibrium rotating at Rhea's angular velocity.[27] Modelling in 2006 suggested that Rhea could be barely capable of sustaining an internal liquid-water ocean through heating by radioactive decay; such an ocean would have to be at about 176 K, the eutectic temperature for the water–ammonia system.[28] More recent indications are that Rhea has a homogeneous interior and hence that this ocean does not exist.[9]

Surface features

[edit]Rhea's features resemble those of Dione, with distinct and dissmillar leading and trailing hemispheres, suggesting similar composition and histories. The temperature on Rhea is 99 K (−174 °C) in direct sunlight and between 73 K (−200 °C) and 53 K (−220 °C) in the shade.

Rhea has a rather typical heavily cratered surface,[29] with the exceptions of a few large Dione-type chasmata or fractures (formerly known as wispy terrain) on the trailing hemisphere (the side facing away from the direction of motion along Rhea's orbit)[30] and a very faint "line" of material at Rhea's equator that may have been deposited by material deorbiting from its rings.[31] Rhea has two very large impact basins on its hemisphere facing away from Saturn, which are about 400 and 500 km across.[30] The more northerly and less degraded of the two, called Tirawa, is roughly comparable in size to the basin Odysseus on Tethys.[29] There is a 48 km-diameter impact crater at 112°W that is prominent because of an extended system of bright rays, which extend up to 400 km (250 mi) away from the crater, across most of one hemisphere.[30][32] This crater, called Inktomi, is nicknamed "The Splat", and may be one of the youngest craters on the inner moons of Saturn. This was hypothesized in a 2007 paper published by Lunar and Planetary Science.[30] Rhea's impact craters are more crisply defined than the flatter craters that are pervasive on Ganymede and Callisto; it is theorized that this is due to a much lower surface gravity (0.26 m/s2, compared to Ganymede's 1.428 m/s2 and Callisto's 1.235 m/s2) and a stiffer crust of ice. Similarly, ejecta blankets – asymmetrical blankets of ejected particles surrounding impact craters – are not present on Rhea, potentially another result of the moon's low surface gravity.[33]

Its surface can be divided into two geologically different areas based on crater density; the first area contains craters which are larger than 40 km in diameter, whereas the second area, in parts of the polar and equatorial regions, has only craters under that size. This suggests that a major resurfacing event occurred some time during its formation. The leading hemisphere is heavily cratered and uniformly bright. As on Callisto, the craters lack the high relief features seen on the Moon and Mercury. It has been theorized that these cratered plains are up to four billion years old on average.[34] On the trailing hemisphere there is a network of bright swaths on a dark background, and fewer craters.[35] It is believed, based on data from the Cassini probe, that these are tectonic features: depressions (graben) and troughs, with ice-covered cliff sides causing the lines' whiteness (more technically their albedo).[36] The extensive dark areas are thought to be deposited tholins, which are a mix of complex organic compounds generated on the ice by pyrolysis and radiolysis of simple compounds containing carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen.[37] The trailing side of Rhea's surface is irradiated by Saturn's magnetosphere, which may cause chemical-level changes on the surface, including radiolysis (see § Atmosphere). Particles from Saturn's E-ring are also flung onto the moon's leading hemisphere, coating it.[38]

Rhea has some evidence of endogenic activity – that is, activity originating from within the moon, such as heating and cryovolcanic activity: there are fault systems and craters with uplifted bases (so-called "relaxed" craters), although the latter is apparently only present in large craters more than 100 km (62 mi) across.[39][40][38]

Formation

[edit]The moons of Saturn are thought to have formed through co-accretion, a similar process to that believed to have formed the planets in the Solar System. As the young giant planets formed, they were surrounded by discs of material that gradually coalesced into moons. However, a model proposed by Erik Asphaug and Andreas Reufer for the formation of Titan may also shine a new light on the origin of Rhea and Iapetus. In this model, Titan was formed in a series of giant impacts between pre-existing moons, and Rhea and Iapetus are thought to have formed from part of the debris of these collisions.[41]

-

Image of the wispy hemisphere, showing ice cliffs – Powehiwehi (upper center); chasmata stretch from upper left to right center – Onokoro Catenae (lower right)

-

View of Rhea's leading hemisphere with crater Inktomi and its prominent ray system just below center; impact basin Tirawa is at upper left

Atmosphere

[edit]On November 27, 2010, NASA announced the discovery of an extremely tenuous atmosphere—an exosphere. It consists of oxygen and carbon dioxide in proportion of roughly 5 to 2. The surface density of the exosphere is from 105 to 106 molecules in a cubic centimeter, depending on local temperature. The main source of oxygen is radiolysis of water ice at the surface via irradiation from the magnetosphere of Saturn. The source of the carbon dioxide is less clear, but it may be related to oxidation of the organics present in ice or to outgassing of the moon's interior.[38][42][43]

Possible ring system

[edit]On March 6, 2008, NASA announced that Rhea may have a weak ring system. This would mark the first discovery of rings around a moon. The rings' existence was inferred by observed changes in the flow of electrons trapped by Saturn's magnetic field as Cassini passed by Rhea.[44][45][46] Dust and debris could extend out to Rhea's Hill sphere, but were thought to be denser nearer the moon, with three narrow rings of higher density. The case for a ring was strengthened by the subsequent finding of the presence of a set of small ultraviolet-bright spots distributed along Rhea's equator (interpreted as the impact points of deorbiting ring material).[47] However, when Cassini made targeted observations of the putative ring plane from several angles, there was no evidence of ring material found, suggesting that another explanation for the earlier observations is needed.[48][49]

Exploration

[edit]The first images of Rhea were obtained by Voyager 1 & 2 spacecraft in 1980–1981.

There were five close targeted fly-bys by the Cassini orbiter, which was one part of the dual orbiter and lander Cassini–Huygens mission. Launched in 1997, Cassini–Huygens was targeted at the Saturn system; in total it took more than 450 thousand images.[50] Cassini passed Rhea at a distance of 500 km on November 26, 2005; at a distance of 5,750 km on August 30, 2007; at a distance of 100 km on March 2, 2010; at 69 km flyby on January 11, 2011;[51] and a last flyby at 992 km on March 9, 2013.[52]

See also

[edit]- Former classification of planets

- List of natural satellites

- Rhea in fiction

- Rings of Rhea

- Subsatellite

- Moons of Saturn

Notes

[edit]- ^ Calculated on the basis of other parameters.

- ^ a b The surface area can be estimated, given the radius, with the formula 4πr2

- ^ Surface area derived from the radius (r): 4\pi r^2.

- ^ The moons more massive than Rhea are: the Moon, the four Galilean moons, Titan, Triton, Titania, and Oberon. Oberon, Uranus's second-largest moon, has a radius that is ~0.4% smaller than Rhea's, but a density that is ~26% greater. See JPLSSD.

- ^ More precisely, 0.3911.[24]

- ^ More precisely, 0.3721.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Tillman, Nola Taylor (2016-06-29). "Rhea: Saturn's dirty snowball moon". space.com.

- ^ Consulmagno, G.; Ryche, H. (Feb 9, 1982). "Pronouncing the names of the moons of Saturn" (PDF). EOS. 63 (6): 146–147. doi:10.1029/EO063i006p00146. Retrieved Nov 30, 2022.

- ^ Moore et al. (1984) "The Geomorphology of Rhea", Proceedings of the fifteenth Lunar and Planetary Science, Part 2, p C-791–C-794

- ^ "Natural Satellites Ephemeris Service". Minor Planet Center.

- ^ a b c d "Saturnian Satellite Fact Sheet". National Space Science Data Center. Archived from the original on 10 Feb 2024.

- ^ Roatsch, T.; Jaumann, R.; Stephan, K.; Thomas, P. C. (2009). "Cartographic Mapping of the Icy Satellites Using ISS and VIMS Data". Saturn from Cassini-Huygens. pp. 763–781. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9217-6_24. ISBN 978-1-4020-9216-9.

- ^ a b c Robert. A. Jacobson (18 October 2022). "The Orbits of the Main Saturnian Satellites, the Saturnian System Gravity Field, and the Orientation of Saturn's Pole". The Astronomical Journal. 164 (5). Bibcode:2022AJ....164..199J. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/AC90C9. ISSN 0004-6256. S2CID 252992162. Wikidata Q126389785.

- ^ Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, G. (2007). "Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (2): L02202. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.2202A. doi:10.1029/2006GL028100.

- ^ a b c Anderson, John D. (July 2008). Rhea's Gravitational Field and Internal Structure. 37th COSPAR Scientific Assembly. Held 13–20 July 2008, in Montréal, Canada. p. 89. Bibcode:2008cosp...37...89A.

- ^ Verbiscer, A.; French, R.; Showalter, M.; Helfenstein, P. (9 February 2007). "Enceladus: Cosmic Graffiti Artist Caught in the Act". Science. 315 (5813): 815. Bibcode:2007Sci...315..815V. doi:10.1126/science.1134681. PMID 17289992. S2CID 21932253. (supporting online material, table S1)

- ^ Observatorio ARVAL (April 15, 2007). "Classic Satellites of the Solar System". Observatorio ARVAL. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ^ David Leverington (29 May 2003). Babylon to Voyager and Beyond: A History of Planetary Astronomy. ISBN 978-0-521-80840-8. LCCN 2002031557. Wikidata Q126386131.

- ^ "In Depth | Rhea". NASA Solar System Exploration. NASA Science. December 19, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ a b "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. July 21, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ As reported by William Lassell, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 42–43 (January 14, 1848)

- ^ "Rhea | 2nd Largest Moon of Saturn | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ "Terms and Definitions". astro.if.ufrgs.br. Retrieved 2024-06-13.

- ^ Julie Castillo-Rogez (17 November 2006). "Internal structure of Rhea". Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (E11). doi:10.1029/2004JE002379. ISSN 0148-0227. S2CID 54034624. Wikidata Q126417371.

- ^ Treatise on Geophysics. Elsevier. 2015-04-17. ISBN 978-0-444-53803-1.

- ^ Hobbs, Peter Victor (2010-05-06). Ice Physics. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-958771-1.

- ^ "Rhea - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ Australia, Geoscience (2014-06-27). "Area of Australia - States and Territories". Geoscience Australia. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ a b Anderson, J. D.; Rappaport, N. J.; Giampieri, G.; et al. (2003). "Gravity field and interior structure of Rhea". Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors. 136 (3–4): 201–213. Bibcode:2003PEPI..136..201A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.7.5250. doi:10.1016/S0031-9201(03)00035-9.

- ^ a b Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, J. (2007). "Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (2): L02202. Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.2202A. doi:10.1029/2006GL028100.

- ^ a b Iess, L.; Rappaport, N.; Tortora, P.; Lunine, Jonathan I.; Armstrong, J.; Asmar, S.; Somenzi, L.; Zingoni, F. (2007). "Gravity field and interior of Rhea from Cassini data analysis". Icarus. 190 (2): 585. Bibcode:2007Icar..190..585I. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.027.

- ^ MacKenzie, R. A.; Iess, L.; Tortora, P.; Rappaport, N. J. (2008). "A non-hydrostatic Rhea". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (5): L05204. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..35.5204M. doi:10.1029/2007GL032898. hdl:11573/17051.

- ^ Thomas, P. C.; Burns, J. A.; Helfenstein, P.; Squyres, S.; Veverka, J.; Porco, C.; Turtle, E. P.; McEwen, A.; Denk, T.; Giesef, B.; Roatschf, T.; Johnsong, T. V.; Jacobsong, R. A. (October 2007). "Shapes of the saturnian icy satellites and their significance" (PDF). Icarus. 190 (2): 573–584. Bibcode:2007Icar..190..573T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.012. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Hussmann, Hauke; Sohl, Frank; Spohn, Tilman (November 2006). "Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects". Icarus. 185 (1): 258–273. Bibcode:2006Icar..185..258H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.06.005.

- ^ a b Moore, Jeffrey M.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bruesch, Lindsey S.; Asphaug, Erik; McKinnon, William B. (October 2004). "Large impact features on middle-sized icy satellites" (PDF). Icarus. 171 (2): 421–443. Bibcode:2004Icar..171..421M. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.009.

- ^ a b c d Wagner, R.J.; Neukum, G.; et al. (2008). "Geology of Saturn's Satellite Rhea on the Basis of the High-Resolution Images from the Targeted Flyby 049 on Aug. 30, 2007". Lunar and Planetary Science. XXXIX (1391): 1930. Bibcode:2008LPI....39.1930W.

- ^ Schenk, Paul M.; McKinnon, W. B. (2009). "Global Color Variations on Saturn's Icy Satellites, and New Evidence for Rhea's Ring". American Astronomical Society. 41: 3.03. Bibcode:2009DPS....41.0303S.

- ^ Schenk, Paul; Kirchoff, Michelle; Hoogenboom, Trudi; Rivera-Valentín, Edgard (2020). "The anatomy of fresh complex craters on the mid-sized icy moons of Saturn and self-secondary cratering at the rayed crater Inktomi (Rhea)". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 55 (11): 2440–2460. Bibcode:2020M&PS...55.2440S. doi:10.1111/maps.13592. ISSN 1086-9379.

- ^ Joseph A. Burns; Mildred Shapley Matthews (November 1986). Satellites. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0983-6. Wikidata Q126417214.

- ^ "Rhea – Overview | Planets – NASA Solar System Exploration". NASA Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 2016-02-14. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Anderson, J. D.; Schubert, G. (18 January 2007). "Saturn's satellite Rhea is a homogeneous mix of rock and ice". Geophysical Research Letters. 34 (2). Bibcode:2007GeoRL..34.2202A. doi:10.1029/2006GL028100. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ^ Wagner, R. J.; Giese, B.; Roatsch, T.; Neukum, G.; Denk, T.; Wolf, U.; Porco, C. C. (May 2010). "Tectonic features on Rhea's trailing hemisphere: a first look at the Cassini ISS camera data from orbit 121, Nov. 21, 2009". EGU General Assembly 2010: 6731. Bibcode:2010EGUGA..12.6731W.

- ^ A spectroscopic study of the surfaces of Saturn's large satellites: H2O ice, tholins, and minor constituents (PDF). Dale P. Cruikshank, Tobias Owen, Cristina Dalle Ore, Thomas R. Geballe, Ted L. Roush, Catherine de Bergh, Scott A. Sandford, Francois Poulet, Gretchen K. Benedix, Joshua P. Emery. Icarus, 175, pages: 268–283, 2 March 2005.

- ^ a b c Elowitz, Mark; Sivaraman, Bhalamurugan; Hendrix, Amanda; Lo, Jen-Iu; Chou, Sheng-Lung; Cheng, Bing-Ming; Sekhar, B. N. Raja; Mason, Nigel J. (2021-01-22). "Possible detection of hydrazine on Saturn's moon Rhea". Science Advances. 7 (4). Bibcode:2021SciA....7.5749E. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba5749. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 10670839. PMID 33523937.

- ^ Aponte-Hernández, Betzaida; Rivera-Valentín, Edgard G.; Kirchoff, Michelle R.; Schenk, Paul M. (Dec 2012). "Morphometric Study of Craters on Saturn's Moon Rhea". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (6): 235. doi:10.3847/psj/ac32d4. ISSN 2632-3338. PMC 8670330. PMID 34913034.

- ^ White, Oliver L.; Schenk, Paul M.; Bellagamba, Anthony W.; Grimm, Ashley M.; Dombard, Andrew J.; Bray, Veronica J. (2017-05-15). "Impact crater relaxation on Dione and Tethys and relation to past heat flow". Icarus. 288: 37–52. Bibcode:2017Icar..288...37W. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2017.01.025. ISSN 0019-1035.

- ^ "Giant impact scenario may explain the unusual moons of Saturn". Space Daily. 2012. Retrieved 2012-10-19.

- ^ "Cassini Finds Ethereal Atmosphere at Rhea". NASA. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Teolis, B. D.; Jones, G. H.; Miles, P. F.; Tokar, R. L.; Magee, B. A.; Waite, J. H.; Roussos, E.; Young, D. T.; Crary, F. J.; Coates, A. J.; Johnson, R. E.; Tseng, W. L.; Baragiola, R. A. (2010). "Cassini Finds an Oxygen–Carbon Dioxide Atmosphere at Saturn's Icy Moon Rhea". Science. 330 (6012): 1813–1815. Bibcode:2010Sci...330.1813T. doi:10.1126/science.1198366. PMID 21109635. S2CID 206530211.

- ^ "Saturn's Moon Rhea Also May Have Rings". NASA. June 3, 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-10-22.

- ^ Jones, G. H.; et al. (2008-03-07). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea". Science. 319 (5868): 1380–1384. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. doi:10.1126/science.1151524. PMID 18323452. S2CID 206509814.

- ^ Lakdawalla, E. (2008-03-06). "A Ringed Moon of Saturn? Cassini Discovers Possible Rings at Rhea". www.planetary.org. Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 2008-03-10. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ^ Lakdawalla, E. (5 October 2009). "Another possible piece of evidence for a Rhea ring". The Planetary Society Blog. Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 2012-02-17. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ^ Matthew S. Tiscareno; Joseph A. Burns; Jeffrey N. Cuzzi; Matthew M. Hedman (2010). "Cassini imaging search rules out rings around Rhea". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (14): L14205. arXiv:1008.1764. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3714205T. doi:10.1029/2010GL043663. S2CID 59458559.

- ^ Kerr, Richard A. (2010-06-25). "The Moon Rings That Never Were". ScienceNow. Archived from the original on 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ^ "Cassini". science.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2024-06-20.

- ^ Cook, Jia-Rui C. (13 January 2011). "Cassini Solstice Mission: Cassini Rocks Rhea Rendezvous". saturn.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ "NASA craft snaps last close-up photos of icy Saturn moon". saturn.jpl.nasa.gov. NASA/JPL. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

External links

[edit]- Rhea Profile at NASA's Solar System Exploration site

- The Planetary Society: Rhea

- Cassini images of Rhea Archived 2011-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Images of Rhea at JPL's Planetary Photojournal

- Movie of Rhea's rotation from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration site

- Rhea global and polar basemaps (March 2012) from Cassini images

- Rhea altlas Archived 2013-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (released December 2010) from Cassini images

- Rhea nomenclature and Rhea map with feature names from the USGS planetary nomenclature page

- Google Rhea 3D, interactive map of the moon

- Saturn's moon Rhea has thin atmosphere

- An extract of the Journal Des Scavans. of April 22 ft. N. 1686. giving an account of two new satellites of Saturn, discovered lately by Mr. Cassini at the Royal Observatory at Paris