Noun phrase: Difference between revisions

possessive pronoun -> possessive adjective |

Reverted 1 edit by 216.48.99.168 (talk): Unconstructive changes to the lede |

||

| (475 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Phrase which grammatically functions the same as a noun}} |

|||

In [[grammar|grammatical theory]], a '''noun phrase''' (abbreviated '''NP''') is a [[phrase]] whose [[Head (linguistics)|head]] is a [[noun]] or a [[pronoun]], optionally accompanied by a set of modifiers. These modifiers may be: |

|||

{{More footnotes needed|date=May 2022}} |

|||

A '''noun phrase''' – or '''NP''' or '''nominal (phrase)''' – is a [[phrase]] that usually has a [[noun]] or [[pronoun]] as its [[head (linguistics)|head]], and has the same [[Grammar|grammatical]] functions as a noun.<ref>For definitions and discussions of the noun (nominal) phrase that point to the presence of a head noun, see for instance Crystal (1997:264), Lockwood (2002:3), and Radford (2004: 14, 348).</ref> Noun phrases are very common [[linguistic typology|cross-linguistically]], and they may be the most frequently occurring phrase type. |

|||

Noun phrases often function as verb [[Subject (grammar)|subject]]s and [[Object (grammar)|object]]s, as [[predicative expression]]s, and as complements of [[preposition and postposition|prepositions]]. One NP can be embedded inside another NP; for instance, ''some of his constituents'' has as a constituent the shorter NP ''his constituents''.<ref>A noun phrase can even serve as the ''head'' of another noun phrase; see Huddleston and Pullum (2002:331) for examples, including the NP ''those copies'' as head of the NP ''both those copies''.</ref> |

|||

*[[Determiner|Determiners]]: [[Article|Articles]] (''the'', ''a''), [[demonstratives]] (''this'', ''that''), [[numerals]] (''two'', ''five'', etc.), [[possessive adjective|possessives]] (''my'', ''their'', etc.), and [[quantifiers]] (''some'', ''many'', etc.) In English determiners are usually placed before the noun. |

|||

*[[Adjective|Adjectives]] (''the '''red''' ball'') |

|||

*[[Complement (linguistics)|Complements]], in the form of an [[adpositional phrase]] (''the man '''with a black hat'''''), or a [[relative clause]] (''the books '''that I bought yesterday'''''). |

|||

In some theories of grammar, noun phrases with [[determiner]]s are analyzed as having the determiner as the head of the phrase, see for instance [[Noam Chomsky|Chomsky]] (1995) and [[Richard Hudson (linguist)|Hudson]] (1990) {{Citation needed|date=June 2024}}. |

|||

In [[English language|English]], for some purposes noun phrases can be treated as single grammatical units. This is most noticeable in the [[syntax]] of the English [[genitive case]]. In a phrase such as ''The King of Sparta's wife'', the possessive [[clitic]] ''<nowiki>'s</nowiki>'' is not added to the ''King'' who actually owns the wife, but instead to ''Sparta'', to which the wife only remotely belongs. The clitic modifies the entire phrase ''King of Sparta''. |

|||

==Identification== |

|||

[[Category:Syntax]] |

|||

Some examples of noun phrases are underlined in the sentences below. The head noun appears in bold. |

|||

::<u>This election-year's '''politics'''</u> are annoying for <u>many '''people'''</u>. |

|||

::<u>Almost every '''sentence'''</u> contains <u>at least one noun '''phrase'''</u>.[[Image:Arkansas Black apples.jpg|thumb|250px|right|''Those five beautiful shiny Arkansas Black apples'' is a noun phrase of which ''apples'' is the [[Head (linguistics)|head]]. To test, a single pronoun can replace the whole noun phrase, as in "''They'' look delicious".]] |

|||

::<u>Current economic '''weakness'''</u> may be <u>a '''result''' of high</u> <u>energy prices</u>. |

|||

Noun phrases can be identified by the possibility of pronoun substitution, as is illustrated in the examples below. |

|||

[[de:Nominalphrase]] |

|||

[[sv:Nominalfras]] |

|||

::a. <u>This '''sentence'''</u> contains <u>two noun '''phrases'''</u>. |

|||

::b. '''It''' contains '''them'''. |

|||

::a. <u>The subject noun '''phrase''' that is present in this sentence</u> is long. |

|||

::b. '''It''' is long. |

|||

::a. <u>Noun '''phrases'''</u> can be embedded in <u>other noun '''phrases'''</u>. |

|||

::b. '''They''' can be embedded in '''them'''. |

|||

A string of words that can be replaced by a single pronoun without rendering the sentence grammatically unacceptable is a noun phrase. As to whether the string must contain at least two words, see the following section. |

|||

==Status of single words as phrases== |

|||

Traditionally, a [[phrase]] is understood to contain two or more [[word]]s. The traditional progression in the size of syntactic units is ''word < phrase < [[clause]]'', and in this approach a single word (such as a noun or pronoun) would not be referred to as a phrase. However, many modern schools of syntax – especially those that have been influenced by [[X-bar theory]] – make no such restriction.<ref>For direct examples of approaches that obscure the distinction between nouns and pronouns on the one hand and noun phrases on the other, see for instance Matthews (1981:160f.) and (Lockwood (2002:3).</ref> Here many single words are judged to be phrases based on a desire for theory-internal consistency. A phrase is deemed to be a word or a combination of words that appears in a set syntactic position, for instance in subject position or object position. |

|||

On this understanding of phrases, the nouns and pronouns in bold in the following sentences are noun phrases (as well as nouns or pronouns): |

|||

::'''He''' saw '''someone'''. |

|||

::'''Milk''' is good. |

|||

::'''They''' spoke about '''corruption'''. |

|||

The words in bold are called phrases since they appear in the syntactic positions where multiple-word phrases (i.e. traditional phrases) can appear. This practice takes the constellation to be primitive rather than the words themselves. The word ''he'', for instance, functions as a pronoun, but within the sentence it also functions as a noun phrase. The [[phrase structure grammar]]s of the Chomskyan tradition ([[government and binding theory]] and the [[minimalist program]]) are primary examples of theories that apply this understanding of phrases. Other grammars such as [[dependency grammar]]s are likely to reject this approach to phrases, since they take the words themselves to be primitive. For them, phrases must contain two or more words. |

|||

==Components== |

|||

A typical noun phrase consists of a noun (the [[head (linguistics)|head]] of the phrase) together with zero or more dependents of various types. (These dependents, since they modify a noun, are called ''adnominal''.) The chief types of these dependents are: |

|||

*[[determiner (linguistics)|determiner]]s, such as ''the'', ''this'', ''my'', ''some'', ''Jane's'' |

|||

*[[attributive adjective]]s, such as ''large'', ''beautiful'', ''sweeter'' |

|||

*[[adjective phrase]]s and [[participial phrase]]s, such as ''extremely large'', ''hard as nails'', ''made of wood'', ''sitting on the step'' |

|||

* [[noun adjunct]]s, such as ''college'' in the noun phrase ''a college student'' |

|||

* nouns in certain [[oblique case]]s, in languages which have them, such as [[German grammar|German]] ''des Mannes'' ("of the man"; [[genitive]] form) |

|||

*[[prepositional phrase]]s, such as ''in the drawing room'', ''of his aunt'' |

|||

*adnominal [[adverb]]s and [[adverbial]]s, such as ''(over) there'' in the noun phrase ''the man (over) there'' |

|||

*[[relative clause]]s, such as ''which we noticed'' |

|||

*other [[clause]]s serving as complements to the noun, such as ''that God exists'' in the noun phrase ''the belief that God exists'' |

|||

*[[infinitive phrase]]s, such as ''to sing well'' and ''to beat'' in the noun phrases ''a desire to sing well'' and ''the man to beat'' |

|||

The allowability, form and position of these elements depend on the syntax of the language in question. In English, determiners, adjectives (and some adjective phrases) and noun modifiers precede the head noun, whereas the heavier units – phrases and clauses – generally follow it. This is part of a strong tendency in English to place heavier constituents to the right, making English more of a [[head-initial]] language. Head-final languages (e.g. [[Japanese language|Japanese]] and [[Turkish language|Turkish]]) are more likely to place all modifiers before the head noun. Other languages, such as [[French language|French]], often place even single-word adjectives after the noun. |

|||

Noun phrases can take different forms than that described above, for example when the head is a pronoun rather than a noun, or when elements are linked with a [[coordinating conjunction]] such as ''and'', ''or'', ''but''. For more information about the structure of noun phrases in English, see {{slink|English grammar|Phrases}}. |

|||

==Syntactic function== |

|||

Noun phrases typically bear [[argument (linguistics)|argument]] functions.<ref>Concerning how noun phrases function, see for instance Stockwell (1977:55ff.).</ref> That is, the [[grammatical relation|syntactic function]]s that they fulfill are those of the arguments of the main clause [[predicate (grammar)|predicate]], particularly those of [[subject (grammar)|subject]], [[object (grammar)|object]] and [[predicative expression]]. They also function as arguments in such constructs as [[participial phrase]]s and [[prepositional phrase]]s. For example: |

|||

::For us <u>the news</u> is a concern. <small>– ''the news'' is the subject argument</small> |

|||

::Have you heard <u>the news</u>? <small>– ''the news'' is the object argument</small> |

|||

::That is <u>the news</u>. <small>– ''the news'' is the predicative expression following the copula ''is''</small> |

|||

::They are talking about <u>the news</u>. <small>– ''the news'' is the argument in the prepositional phrase ''about the news''</small> |

|||

::The man reading <u>the news</u> is very tall. <small>– ''the news'' is the object argument in the participial phrase ''reading the news''</small> |

|||

Sometimes a noun phrase can also function as an [[Adjunct (grammar)|adjunct]] of the main clause predicate, thus taking on an [[adverb]]ial function, e.g. |

|||

::<u>Most days</u> I read the newspaper. |

|||

::She has been studying <u>all night</u>. |

|||

==With and without determiners== |

|||

In some languages, including English, noun phrases are required to be "completed" with a [[determiner (linguistics)|determiner]] in many contexts, and thus a distinction is made in syntactic analysis between phrases that have received their required determiner (such as ''the big house''), and those in which the determiner is lacking (such as ''big house''). |

|||

The situation is complicated by the fact that in some contexts a noun phrase may nonetheless be used without a determiner (as in ''I like big houses''); in this case the phrase may be described as having a "null determiner". (Situations in which this is possible depend on the rules of the language in question; for English, see [[English articles]].) |

|||

In the original [[X-bar theory]], the two respective types of entity are called noun phrase (NP) and N-bar (<span style="text-decoration:overline">N</span>, N{{prime}}). Thus in the sentence ''Here is the big house'', both ''house'' and ''big house'' are N-bars, while ''the big house'' is a noun phrase. In the sentence ''I like big houses'', both ''houses'' and ''big houses'' are N-bars, but ''big houses'' also functions as a noun phrase (in this case without an explicit determiner). |

|||

In some modern theories of syntax, however, what are called "noun phrases" above are no longer considered to be headed by a noun, but by the determiner (which may be null), and they are thus called ''[[determiner phrase]]s'' (DP) instead of noun phrases. (In some accounts that take this approach, the constituent lacking the determiner – that called N-bar above – may be referred to as a noun phrase.) |

|||

This analysis of noun phrases is widely referred to as the ''DP hypothesis''. It has been the preferred analysis of noun phrases in the [[minimalist program]] from its start (since the early 1990s), though the arguments in its favor tend to be theory-internal. By taking the determiner, a function word, to be head over the noun, a structure is established that is analogous to the structure of the [[finite clause]], with a [[complementizer]]. Apart from the minimalist program, however, the DP hypothesis is rejected by most other modern theories of syntax and grammar, in part because these theories lack the relevant functional categories.<ref>For discussion and criticism of the DP analysis of noun phrases, see Matthews (2007:12ff.).</ref> Dependency grammars, for instance, almost all assume the traditional NP analysis of noun phrases. |

|||

For illustrations of different analyses of noun phrases depending on whether the DP hypothesis is rejected or accepted, see the next section. |

|||

==Tree representations== |

|||

The representation of noun phrases using [[parse tree]]s depends on the basic approach to syntactic structure adopted. The layered trees of many [[phrase structure grammar]]s grant noun phrases an intricate structure that acknowledges a hierarchy of functional projections. [[Dependency grammar]]s, in contrast, since the basic architecture of dependency places a major limitation on the amount of structure that the theory can assume, produce simple, relatively flat structures for noun phrases. |

|||

The representation also depends on whether the noun or the determiner is taken to be the head of the phrase (see the discussion of the DP hypothesis in the previous section). |

|||

Below are some possible trees for the two noun phrases ''the big house'' and ''big houses'' (as in the sentences ''Here is the big house'' and ''I like big houses''). |

|||

1. [[Phrase-structure grammar|Phrase-structure]] trees, first using the original X-bar theory, then using the current DP approach: |

|||

<pre> |

|||

NP NP | DP DP |

|||

/ \ | | / \ | |

|||

det N' N' | det NP NP |

|||

| / \ / \ | | / \ / \ |

|||

the adj N' adj N' | the adj NP adj NP |

|||

| | | | | | | | | |

|||

big N big N | big N big N |

|||

| | | | | |

|||

house houses | house houses |

|||

</pre> |

|||

2. [[Dependency grammar|Dependency]] trees, first using the traditional NP approach, then using the DP approach: |

|||

<pre> |

|||

house houses | the (null) |

|||

/ / / | \ \ |

|||

/ / big | house houses |

|||

the big | / / |

|||

| big big |

|||

</pre> |

|||

The following trees represent a more complex phrase. For simplicity, only dependency-based trees are given.<ref>For a dependency grammar analysis of noun phrases similar to the one represented by the trees here, see for instance Starosta (1988:219ff.). For an example of a relatively "flat" analysis of NP structure like the one produced here, but in a phrase structure grammar, see Culicover and Jackendoff (2005:140).</ref> |

|||

The first tree is based on the traditional assumption that nouns, rather than determiners, are the heads of phrases. |

|||

::[[File:Noun phrase tree 1.png|Noun phrase tree 1]] |

|||

The head noun ''picture'' has the four dependents ''the'', ''old'', ''of Fred'', and ''that I found in the drawer''. The tree shows how the lighter dependents appear as pre-dependents (preceding their head) and the heavier ones as post-dependents (following their head). |

|||

The second tree assumes the DP hypothesis, namely that determiners serve as phrase heads, rather than nouns. |

|||

::[[File:Noun phrase tree 2'.png|Noun phrase tree 2']] |

|||

The determiner ''the'' is now depicted as the head of the entire phrase, thus making the phrase a determiner phrase. There is still a noun phrase present (''old picture of Fred that I found in the drawer'') but this phrase is below the determiner. |

|||

== History == |

|||

An early conception of the noun phrase can be found in ''First work in English'' by [[Alexander Murison]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Murison |first=Alexander |title=First Work in English: Grammar and Composition Taught by a Comparative Study of Equivalent Forms |publisher=[[Longman]], Green, and Co. |year=1875 |location=Aberdeen}}</ref> In this conception a noun phrase is "the infinitive of the verb" (p. 146), which may appear "in any position in the sentence where a noun may appear". For example, ''<u>to be just</u> is more important than <u>to be generous</u>'' has two underlined infinitives which may be replaced by nouns, as in ''justice is more important than generosity''. This same conception can be found in subsequent grammars, such as 1878's ''A Tamil Grammar''<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lazarus |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=718IAAAAQAAJ&dq=%22noun+phrase%22&pg=PA198 |title=A Tamil Grammar, Designed for Use in Colleges and Schools |date=1878 |publisher=Addison & Company |language=ta}}</ref> or 1882's ''Murby's English grammar and analysis'', where the conception of an X phrase is a phrase that can stand in for X.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Robertson |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U3ICAAAAQAAJ |title=Murby's English grammar and analysis, taught simultaneously |date=1882 |language=en}}</ref> By 1912, the concept of a noun phrase as being based around a noun can be found, for example, "an adverbial noun phrases is a group of words of which the noun is the base word, that tells the time or place of an action, or how long, how far, or how much".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kimball |first1=Lillian Gertrude |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZkJKAAAAIAAJ&dq=participial+phrase&pg=PA232 |title=English Grammar |date=1912 |publisher=American Book Company |page=91 |access-date=29 December 2020}}</ref> By 1924, the idea of a noun phrase being a noun plus dependents seems to be established. For example, "Note order of words in noun-phrase--noun + adj. + genitive" suggests <ref>{{Cite book |last=Gadd |first=Cyril John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=89ILAwAAQBAJ |title=A Sumerian Reading-Book |year=1924 |pages=45|publisher=Рипол Классик |isbn=9785873153022 }}</ref> a more modern conception of noun phrases. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Chunking (computational linguistics)]] |

|||

* [[Conservativity]] |

|||

* [[Nominal group (functional grammar)]] |

|||

==Footnotes== |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Chomsky, N.|author-link=Noam Chomsky|year=1995|title=The Minimalist Program|location=Cambridge, MA|publisher=The MIT Press}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Crystal, D.|author-link=David Crystal|year=1997|title=A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics|publisher=Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers|url=http://data.ulis.vnu.edu.vn/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1966/1/54_1405152974.pdf|isbn=978-1-405-15296-9|access-date=2015-04-28|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150724051925/http://data.ulis.vnu.edu.vn/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1966/1/54_1405152974.pdf|archive-date=2015-07-24|url-status=dead}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=[[Peter Culicover|Culicover, P.]] and [[Ray Jackendoff|R. Jackendoff]]|year=2005|title=[[Simpler syntax]]|location=Oxford, UK|publisher=Oxford University Press}} |

|||

*Huddleston, R. and G. K. Pullum (2002). ''The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Hudson, R.|author-link=Richard Hudson (linguist)|year=1990|title=English Word Grammar|location=Oxford|publisher=Basil Blackwell}} |

|||

*Lockwood, D. 2002. Syntactic analysis and description: A constructional approach. London: Continuum. |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Matthews, P.|author-link=Peter Hugoe Matthews|year=1981|title=Syntax|location=Cambridge, UK|publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Matthews, P.|year=2007|title=Syntactic relations: A critical survey|location=Cambridge, UK|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-60829-9}} |

|||

*[[Andrew Radford (linguist)|Radford, A.]] 2004. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Starosta, S.|year=1988|title=The case for lexicase|location=London|publisher=Pinter Publishers|isbn=0-86187-639-3}} |

|||

*Stockwell, P. 1977. Foundations of syntactic theory Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. |

|||

See also: |

|||

*Rijkhoff, Jan. 2008. Descriptive and discourse-referential modifiers in a layered model of the noun phrase. Linguistics 46–4, 789–829. |

|||

* {{cite book |doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237822.001.0001 |title=The Noun Phrase |year=2002 |last1=Rijkhoff |first1=Jan |isbn=978-0-19-823782-2 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |doi=10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.53031-1 |chapter=Word Order |title=International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences |year=2015 |last1=Rijkhoff |first1=Jan |pages=644–656 |isbn=978-0-08-097087-5 |url=https://pure.au.dk/ws/files/90431351/Word_Order_draft_May_2014.pdf }} |

|||

*García Velasco, Daniel and Jan Rijkhoff (eds.).2008. The Noun Phrase in Functional Discourse Grammar (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM] 195). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Syntactic categories]] |

|||

[[Category:Grammatical construction types]] |

|||

[[Category:Phrases|*]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 09:43, 27 October 2024

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2022) |

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun.[1] Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently occurring phrase type.

Noun phrases often function as verb subjects and objects, as predicative expressions, and as complements of prepositions. One NP can be embedded inside another NP; for instance, some of his constituents has as a constituent the shorter NP his constituents.[2]

In some theories of grammar, noun phrases with determiners are analyzed as having the determiner as the head of the phrase, see for instance Chomsky (1995) and Hudson (1990) [citation needed].

Identification

[edit]Some examples of noun phrases are underlined in the sentences below. The head noun appears in bold.

- This election-year's politics are annoying for many people.

- Almost every sentence contains at least one noun phrase.

Those five beautiful shiny Arkansas Black apples is a noun phrase of which apples is the head. To test, a single pronoun can replace the whole noun phrase, as in "They look delicious". - Current economic weakness may be a result of high energy prices.

Noun phrases can be identified by the possibility of pronoun substitution, as is illustrated in the examples below.

- a. This sentence contains two noun phrases.

- b. It contains them.

- a. The subject noun phrase that is present in this sentence is long.

- b. It is long.

- a. Noun phrases can be embedded in other noun phrases.

- b. They can be embedded in them.

A string of words that can be replaced by a single pronoun without rendering the sentence grammatically unacceptable is a noun phrase. As to whether the string must contain at least two words, see the following section.

Status of single words as phrases

[edit]Traditionally, a phrase is understood to contain two or more words. The traditional progression in the size of syntactic units is word < phrase < clause, and in this approach a single word (such as a noun or pronoun) would not be referred to as a phrase. However, many modern schools of syntax – especially those that have been influenced by X-bar theory – make no such restriction.[3] Here many single words are judged to be phrases based on a desire for theory-internal consistency. A phrase is deemed to be a word or a combination of words that appears in a set syntactic position, for instance in subject position or object position.

On this understanding of phrases, the nouns and pronouns in bold in the following sentences are noun phrases (as well as nouns or pronouns):

- He saw someone.

- Milk is good.

- They spoke about corruption.

The words in bold are called phrases since they appear in the syntactic positions where multiple-word phrases (i.e. traditional phrases) can appear. This practice takes the constellation to be primitive rather than the words themselves. The word he, for instance, functions as a pronoun, but within the sentence it also functions as a noun phrase. The phrase structure grammars of the Chomskyan tradition (government and binding theory and the minimalist program) are primary examples of theories that apply this understanding of phrases. Other grammars such as dependency grammars are likely to reject this approach to phrases, since they take the words themselves to be primitive. For them, phrases must contain two or more words.

Components

[edit]A typical noun phrase consists of a noun (the head of the phrase) together with zero or more dependents of various types. (These dependents, since they modify a noun, are called adnominal.) The chief types of these dependents are:

- determiners, such as the, this, my, some, Jane's

- attributive adjectives, such as large, beautiful, sweeter

- adjective phrases and participial phrases, such as extremely large, hard as nails, made of wood, sitting on the step

- noun adjuncts, such as college in the noun phrase a college student

- nouns in certain oblique cases, in languages which have them, such as German des Mannes ("of the man"; genitive form)

- prepositional phrases, such as in the drawing room, of his aunt

- adnominal adverbs and adverbials, such as (over) there in the noun phrase the man (over) there

- relative clauses, such as which we noticed

- other clauses serving as complements to the noun, such as that God exists in the noun phrase the belief that God exists

- infinitive phrases, such as to sing well and to beat in the noun phrases a desire to sing well and the man to beat

The allowability, form and position of these elements depend on the syntax of the language in question. In English, determiners, adjectives (and some adjective phrases) and noun modifiers precede the head noun, whereas the heavier units – phrases and clauses – generally follow it. This is part of a strong tendency in English to place heavier constituents to the right, making English more of a head-initial language. Head-final languages (e.g. Japanese and Turkish) are more likely to place all modifiers before the head noun. Other languages, such as French, often place even single-word adjectives after the noun.

Noun phrases can take different forms than that described above, for example when the head is a pronoun rather than a noun, or when elements are linked with a coordinating conjunction such as and, or, but. For more information about the structure of noun phrases in English, see English grammar § Phrases.

Syntactic function

[edit]Noun phrases typically bear argument functions.[4] That is, the syntactic functions that they fulfill are those of the arguments of the main clause predicate, particularly those of subject, object and predicative expression. They also function as arguments in such constructs as participial phrases and prepositional phrases. For example:

- For us the news is a concern. – the news is the subject argument

- Have you heard the news? – the news is the object argument

- That is the news. – the news is the predicative expression following the copula is

- They are talking about the news. – the news is the argument in the prepositional phrase about the news

- The man reading the news is very tall. – the news is the object argument in the participial phrase reading the news

Sometimes a noun phrase can also function as an adjunct of the main clause predicate, thus taking on an adverbial function, e.g.

- Most days I read the newspaper.

- She has been studying all night.

With and without determiners

[edit]In some languages, including English, noun phrases are required to be "completed" with a determiner in many contexts, and thus a distinction is made in syntactic analysis between phrases that have received their required determiner (such as the big house), and those in which the determiner is lacking (such as big house).

The situation is complicated by the fact that in some contexts a noun phrase may nonetheless be used without a determiner (as in I like big houses); in this case the phrase may be described as having a "null determiner". (Situations in which this is possible depend on the rules of the language in question; for English, see English articles.)

In the original X-bar theory, the two respective types of entity are called noun phrase (NP) and N-bar (N, N′). Thus in the sentence Here is the big house, both house and big house are N-bars, while the big house is a noun phrase. In the sentence I like big houses, both houses and big houses are N-bars, but big houses also functions as a noun phrase (in this case without an explicit determiner).

In some modern theories of syntax, however, what are called "noun phrases" above are no longer considered to be headed by a noun, but by the determiner (which may be null), and they are thus called determiner phrases (DP) instead of noun phrases. (In some accounts that take this approach, the constituent lacking the determiner – that called N-bar above – may be referred to as a noun phrase.)

This analysis of noun phrases is widely referred to as the DP hypothesis. It has been the preferred analysis of noun phrases in the minimalist program from its start (since the early 1990s), though the arguments in its favor tend to be theory-internal. By taking the determiner, a function word, to be head over the noun, a structure is established that is analogous to the structure of the finite clause, with a complementizer. Apart from the minimalist program, however, the DP hypothesis is rejected by most other modern theories of syntax and grammar, in part because these theories lack the relevant functional categories.[5] Dependency grammars, for instance, almost all assume the traditional NP analysis of noun phrases.

For illustrations of different analyses of noun phrases depending on whether the DP hypothesis is rejected or accepted, see the next section.

Tree representations

[edit]The representation of noun phrases using parse trees depends on the basic approach to syntactic structure adopted. The layered trees of many phrase structure grammars grant noun phrases an intricate structure that acknowledges a hierarchy of functional projections. Dependency grammars, in contrast, since the basic architecture of dependency places a major limitation on the amount of structure that the theory can assume, produce simple, relatively flat structures for noun phrases.

The representation also depends on whether the noun or the determiner is taken to be the head of the phrase (see the discussion of the DP hypothesis in the previous section).

Below are some possible trees for the two noun phrases the big house and big houses (as in the sentences Here is the big house and I like big houses).

1. Phrase-structure trees, first using the original X-bar theory, then using the current DP approach:

NP NP | DP DP

/ \ | | / \ |

det N' N' | det NP NP

| / \ / \ | | / \ / \

the adj N' adj N' | the adj NP adj NP

| | | | | | | | |

big N big N | big N big N

| | | | |

house houses | house houses

2. Dependency trees, first using the traditional NP approach, then using the DP approach:

house houses | the (null)

/ / / | \ \

/ / big | house houses

the big | / /

| big big

The following trees represent a more complex phrase. For simplicity, only dependency-based trees are given.[6]

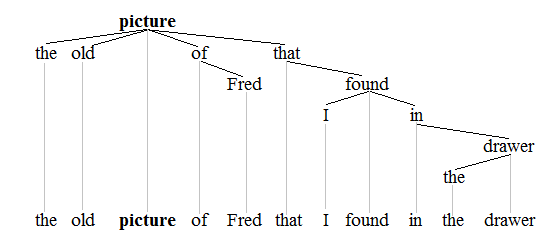

The first tree is based on the traditional assumption that nouns, rather than determiners, are the heads of phrases.

The head noun picture has the four dependents the, old, of Fred, and that I found in the drawer. The tree shows how the lighter dependents appear as pre-dependents (preceding their head) and the heavier ones as post-dependents (following their head).

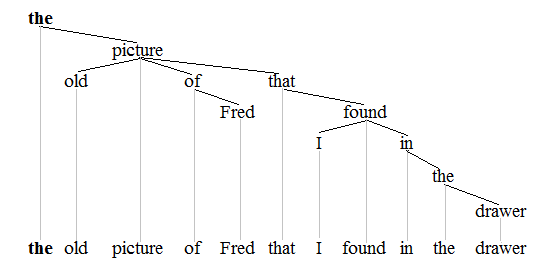

The second tree assumes the DP hypothesis, namely that determiners serve as phrase heads, rather than nouns.

The determiner the is now depicted as the head of the entire phrase, thus making the phrase a determiner phrase. There is still a noun phrase present (old picture of Fred that I found in the drawer) but this phrase is below the determiner.

History

[edit]An early conception of the noun phrase can be found in First work in English by Alexander Murison.[7] In this conception a noun phrase is "the infinitive of the verb" (p. 146), which may appear "in any position in the sentence where a noun may appear". For example, to be just is more important than to be generous has two underlined infinitives which may be replaced by nouns, as in justice is more important than generosity. This same conception can be found in subsequent grammars, such as 1878's A Tamil Grammar[8] or 1882's Murby's English grammar and analysis, where the conception of an X phrase is a phrase that can stand in for X.[9] By 1912, the concept of a noun phrase as being based around a noun can be found, for example, "an adverbial noun phrases is a group of words of which the noun is the base word, that tells the time or place of an action, or how long, how far, or how much".[10] By 1924, the idea of a noun phrase being a noun plus dependents seems to be established. For example, "Note order of words in noun-phrase--noun + adj. + genitive" suggests [11] a more modern conception of noun phrases.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ For definitions and discussions of the noun (nominal) phrase that point to the presence of a head noun, see for instance Crystal (1997:264), Lockwood (2002:3), and Radford (2004: 14, 348).

- ^ A noun phrase can even serve as the head of another noun phrase; see Huddleston and Pullum (2002:331) for examples, including the NP those copies as head of the NP both those copies.

- ^ For direct examples of approaches that obscure the distinction between nouns and pronouns on the one hand and noun phrases on the other, see for instance Matthews (1981:160f.) and (Lockwood (2002:3).

- ^ Concerning how noun phrases function, see for instance Stockwell (1977:55ff.).

- ^ For discussion and criticism of the DP analysis of noun phrases, see Matthews (2007:12ff.).

- ^ For a dependency grammar analysis of noun phrases similar to the one represented by the trees here, see for instance Starosta (1988:219ff.). For an example of a relatively "flat" analysis of NP structure like the one produced here, but in a phrase structure grammar, see Culicover and Jackendoff (2005:140).

- ^ Murison, Alexander (1875). First Work in English: Grammar and Composition Taught by a Comparative Study of Equivalent Forms. Aberdeen: Longman, Green, and Co.

- ^ Lazarus, John (1878). A Tamil Grammar, Designed for Use in Colleges and Schools (in Tamil). Addison & Company.

- ^ Robertson, John (1882). Murby's English grammar and analysis, taught simultaneously.

- ^ Kimball, Lillian Gertrude (1912). English Grammar. American Book Company. p. 91. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Gadd, Cyril John (1924). A Sumerian Reading-Book. Рипол Классик. p. 45. ISBN 9785873153022.

References

[edit]- Chomsky, N. (1995). The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Crystal, D. (1997). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (PDF). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 978-1-405-15296-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- Culicover, P. and R. Jackendoff (2005). Simpler syntax. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Huddleston, R. and G. K. Pullum (2002). The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hudson, R. (1990). English Word Grammar. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Lockwood, D. 2002. Syntactic analysis and description: A constructional approach. London: Continuum.

- Matthews, P. (1981). Syntax. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Matthews, P. (2007). Syntactic relations: A critical survey. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60829-9.

- Radford, A. 2004. English syntax: An introduction. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Starosta, S. (1988). The case for lexicase. London: Pinter Publishers. ISBN 0-86187-639-3.

- Stockwell, P. 1977. Foundations of syntactic theory Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc.

See also:

- Rijkhoff, Jan. 2008. Descriptive and discourse-referential modifiers in a layered model of the noun phrase. Linguistics 46–4, 789–829.

- Rijkhoff, Jan (2002). The Noun Phrase. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237822.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-823782-2.

- Rijkhoff, Jan (2015). "Word Order". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (PDF). pp. 644–656. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.53031-1. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5.

- García Velasco, Daniel and Jan Rijkhoff (eds.).2008. The Noun Phrase in Functional Discourse Grammar (Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs [TiLSM] 195). Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter.