Animals in Meitei culture: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 18 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Accounts on animals in Meitei culture}} |

{{Short description|Accounts on animals in Meitei culture}} |

||

{{Contains special characters|Meitei}} |

{{Contains special characters|Meitei}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Use Indian English|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Paphal (Musée du Quai Branly) (4489839164).jpg|thumb|A sculpture of [[Poubi Lai]], being displayed in the [[Quai Branly Museum]], Paris, France in 2010]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | However, when he heard the news that his sweetheart lady |

||

| ⚫ | Animals ({{langx|mni|{{Script|Latn|Saa/Shaa}}|}}) have significant roles in different elements of [[Meitei culture]], including but not limited to [[Meitei cuisine]], [[Meitei dances]], [[Meitei festivals]], [[Meitei folklore]], [[Meitei folktales]], [[Meitei literature]], [[Meitei mythology]], [[Sanamahism|Meitei religion]], etc. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | However, when he heard the news that his sweetheart lady married King Laijing Ningthou Punsiba of [[ancient Moirang]], during his absence, he got extremely disappointed and sad. And so, with the painful and sad feelings, he realised and sensed the feelings of the deer for getting separated from its mate (partner). So, he released the deer in the wild of the Keibul Lamjao (modern day [[Keibul Lamjao National Park]] regions). Since then, the Sangai species started living in the Keibul Lamjao region as their natural habitat.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2014-02-01 |title=State Animal Sangai |url=http://environmentmanipur.com/State%20Animal%20Sangai.html |access-date=2022-10-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140201232639/http://environmentmanipur.com/State%20Animal%20Sangai.html |archive-date=2014-02-01 |quote=Sangai is a glittering gem in the rich cultural heritage of Kangleipak (Manipur). It is said that a legendary hero Kadeng Thangjahanba of Moirang once captured a gravid Sangai from Torbung Lamjao for a loving gift to his beloved Tonu Laijinglembi. But as ill luck would have it, he found his beloved to be at the palace of the king as his spouse and, as such, all his hopes were shattered. In desperation, the hero released the deer free in the wild of Keibul Lamjao and from that time onwards the place became the home of Sangai.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Khaute |first=Lallian Mang |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e3X9zkP5jKUC&dq=Tonu+Laijinglembi&pg=PA55 |title=The Sangai: The Pride of Manipur |date=2010 |publisher= Gyan Publishing House|isbn=978-81-7835-772-0 |pages=55 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

== Dogs in Meitei culture == |

== Dogs in Meitei culture == |

||

Dogs are mentioned as friends or companions of human beings, in many ancient tales and texts. In many cases, when dogs died, they were given respect by performing elaborate death ceremonies, equal to that of human beings.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Ch Manihar |title=A History of Manipuri Literature |date=1996 |publisher=[[Sahitya Akademi]] |isbn=978-81-260-0086-9 |page=201 |language=en, mni}}</ref> |

Dogs are mentioned as friends or companions of human beings, in many ancient tales and texts. In many cases, when dogs died, they were given respect by performing elaborate death ceremonies, equal to that of human beings.<ref name="Singh 1996 201">{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Ch Manihar |title=A History of Manipuri Literature |date=1996 |publisher=[[Sahitya Akademi]] |isbn=978-81-260-0086-9 |page=201 |language=en, mni}}</ref> |

||

When goddess [[Konthoujam Tampha Lairembi]] saw smokes in her native place, she was restless. She came down to earth from heaven to find out who was dead. On reaching the place, her mother told her as follows: |

When goddess [[Konthoujam Tampha Lairembi]] saw smokes in her native place, she was restless. She came down to earth from heaven to find out who was dead. On reaching the place, her mother told her as follows: |

||

{{ |

{{Blockquote|''"O daughter of mine, none of your parents or brothers ever dies. The watchful dog of your Lord Soraren kept amidst us was fatally bitten by a snake. Only we performed its last rites."''|Konthoucham Nongkalol (Konthoujam Nonggarol)<ref name="Singh 1996 201">{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=Ch Manihar |title=A History of Manipuri Literature |date=1996 |publisher=[[Sahitya Akademi]] |isbn=978-81-260-0086-9 |page=201 |language=en, mni}}</ref>}} |

||

== Elephants in Meitei culture {{anchor|Elephant in Meitei culture|Tusker in Meitei culture|Tuskers in Meitei culture}} == |

== Elephants in Meitei culture {{anchor|Elephant in Meitei culture|Tusker in Meitei culture|Tuskers in Meitei culture}} == |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Khamba and Thoibi#Torture by the elephant}} |

||

[[File:Plate_8-2_Folk-Lore,_vol._24.jpg|thumb |

[[File:Plate_8-2_Folk-Lore,_vol._24.jpg|thumb|"Kang Chingba" festival celebrated by the [[Meitei people]] in [[Manipur]] in the 20th century]] |

||

[[File:KHAMBA THOIBI EPIC - THE TORTURE BY THE ELEPHANT.jpg|thumb |

[[File:KHAMBA THOIBI EPIC - THE TORTURE BY THE ELEPHANT.jpg|thumb |An elephant torturing [[Khuman Khamba]] in the [[Meitei folklore|Meitei]] epic legend of [[Khamba and Thoibi]] of [[Moirang]], southern [[Kangleipak]]]] |

||

In the Meitei epic of the [[Khamba and Thoibi]], the crown prince Chingkhu Akhuba of [[ancient Moirang]] and [[Nongban|Kongyamba]], planned to kill to [[Khuman Khamba]].<ref name=" |

In the Meitei epic of the [[Khamba and Thoibi]], the crown prince Chingkhu Akhuba of [[ancient Moirang]] and [[Nongban|Kongyamba]], planned to kill to [[Khuman Khamba]].<ref name="hodson">{{Cite book |last=T.C. Hodson |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.158175/page/n170/mode/1up?view=theater |title=The Meitheis |date=1908 |publisher=[[David Nutt (publisher)|David Nutt]] |location=London |page=146 |language=en-GB}}</ref> |

||

Kongyamba and his accomplices together threatened Khamba to give up [[Moirang Thoibi]], which Khamba rejected. Then they fought, and Khamba bet all of them, and was about to kill Kongyamba, but the men that stood by, the friends of Kongyamba, dragged Khamba off, and bound him to the elephant of the crown prince, with ropes. Then they goaded the elephant, but the God [[Thangching]] stayed it so that it didn't move. Finally, Kongyamba lost patience. He pricked a spear to the elephant so that it moved in the pain. But it still didn't harm Khamba. Khamba seemed to be dead. Meanwhile, on the other hand, Goddess [[Panthoibi]] came in a dream to Thoibi and told her everything that was happening. So, Thoibi rushed to the spot and saved Khamba from the elephant torture. |

Kongyamba and his accomplices together threatened Khamba to give up [[Moirang Thoibi]], which Khamba rejected. Then they fought, and Khamba bet all of them, and was about to kill Kongyamba, but the men that stood by, the friends of Kongyamba, dragged Khamba off, and bound him to the elephant of the crown prince, with ropes. Then they goaded the elephant, but the God [[Thangching]] stayed it so that it didn't move. Finally, Kongyamba lost patience. He pricked a spear to the elephant so that it moved in the pain. But it still didn't harm Khamba. Khamba seemed to be dead. Meanwhile, on the other hand, Goddess [[Panthoibi]] came in a dream to Thoibi and told her everything that was happening. So, Thoibi rushed to the spot and saved Khamba from the elephant torture.{{r|hodson|p=147}} |

||

== Fishes in Meitei culture == |

== Fishes in Meitei culture == |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Emoinu Eratpa|Emoinu Fish Fest}} |

||

[[File:Dried freshwater fish.JPG|thumb |

[[File:Dried freshwater fish.JPG|thumb|Dried freshwater fish sold at the {{langnf|mni|[[Ima Keithel]]|[[Ima Market]]}} in [[Imphal]]]] |

||

[[File:Assorted dried fishes.JPG |

[[File:Assorted dried fishes.JPG|thumb|Dried freshwater fish sold at the {{langnf|mni|[[Ima Keithel]]|[[Ima Market]]}} in [[Imphal]]]] |

||

[[File:Pakhangba.jpg|thumb|This is what Pakhangba is said to look like. He is a very powerful, strong-minded dragon. He has the respect of those around him.]] |

|||

== Horses in Meitei culture == |

== Horses in Meitei culture == |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Samaton|Sagol Kangjei|Marjing Polo Statue}} |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Marjing Polo Statue — World's tallest statue of a polo player.jpg|thumb|[[Marjing Polo Statue]], the world's tallest polo player statue, standing inside the [[Marjing Polo Complex]], dedicated to God [[Marjing]], the [[ancient Meitei deity]] of {{langnf|mni|[[Sagol Kangjei]]|[[polo]]}} and [[Manipuri pony|Meitei horses]] ([[Manipuri pony]]), in the [[Heingang Ching]]]] |

||

[[File:Statue of Maharaja Nara Singh in front of the Western Entrance to the Kangla fort in Imphal.jpg|thumb |

[[File:Statue of Maharaja Nara Singh in front of the Western Entrance to the Kangla fort in Imphal.jpg|thumb|Statue of [[Raja Nara Singh|Meidingu Nara Singh]] (1844-1850 A.D.) in front of the [[Kangla Sanathong]], the Western Entrance to the [[Kangla Fort]] in [[Imphal]]]] |

||

== Lions in Meitei culture == |

== Lions in Meitei culture == |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Nongshāba|Kanglā Shā}} |

||

[[File:Uttra Sanglen.JPG|thumb |

[[File:Uttra Sanglen.JPG|thumb|The dual statues dedicated to [[Kangla Sha]] alias [[Nongshaba]], the dragon lion of [[Sanamahism|Meitei religion]], installed inside the [[Kangla Fort]] of [[Kangleipak]]]] |

||

=== Kanglā Shā === |

=== Kanglā Shā === |

||

In [[Meitei mythology]] and [[ |

In [[Meitei mythology]] and [[Sanamahism|religion]], {{langnf|mni|'''Kangla Sa'''|Beast of the [[Kangla]]}}, also spelled as {{lang|mni|'''Kangla Sha'''}}, is a guardian dragon lion, whose appearance is described as a creature with a lion's body and a dragon's head, and two horns. Besides being sacred to the [[Meitei cultural heritage]],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chakravarti |first=Sudeep |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=e11PEAAAQBAJ&q=kanglasha+lion%27s+body+dragon+head+meitei+heritage&pg=PT254 |title=The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India's Far East |date=2022-01-06 |publisher=[[Simon and Schuster]] |isbn=978-93-92099-26-7 |pages=254 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Session |first=North East India History Association |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mjRuAAAAMAAJ&q=kanglasha |title=Proceedings of North East India History Association |date=1990 |publisher=The Association |others=Original from:the [[University of Michigan]] |pages=133, 134 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

it is frequently |

it is frequently portrayed in the royal symbol of the [[Ningthouja dynasty|Meitei royalties]] ([[Ningthouja dynasty]]).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bhattacharyya |first=Rituparna |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DEZ1EAAAQBAJ&q=The+mythical+animal+called+Kangla+Sha%2C+which+became+a+symbol%2C+was+believed.&pg=PT203 |title=Northeast India Through the Ages: A Transdisciplinary Perspective on Prehistory, History, and Oral History |date=2022-07-29 |publisher=[[Taylor & Francis]] |isbn=978-1-000-62390-1 |pages=203 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

The most popular iconographic colossal statues of the "Kangla Sa" stand inside the [[Kangla Fort]] in [[Imphal]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=N. Joykumar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r1xuAAAAMAAJ&q=construction+Kangla+Sa+Lion+like+animal+front+gate+Kangla+great+achievement+beautification+programme |title=Colonialism to Democracy: A History of Manipur, 1819-1972 |date=2002 |publisher=Spectrum Publications |others=Original from : the [[University of Michigan]] |isbn=978-81-87502-44-9 |pages=7 |language=en |quote=The construction of ' Kangla Sa ' (Lion like animal) at the front of the gate of Kangla was a great achievement of his beautification programme.}}</ref> |

The most popular iconographic colossal statues of the "Kangla Sa" stand inside the [[Kangla Fort]] in [[Imphal]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=N. Joykumar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r1xuAAAAMAAJ&q=construction+Kangla+Sa+Lion+like+animal+front+gate+Kangla+great+achievement+beautification+programme |title=Colonialism to Democracy: A History of Manipur, 1819-1972 |date=2002 |publisher=Spectrum Publications |others=Original from : the [[University of Michigan]] |isbn=978-81-87502-44-9 |pages=7 |language=en |quote=The construction of ' Kangla Sa ' (Lion like animal) at the front of the gate of Kangla was a great achievement of his beautification programme.}}</ref> |

||

In Meitei traditional race competitions, winners of the race are declared only after symbolically touching the statue of the dragon "Kangla Sha". This ideology is clearly mentioned in the story of |

In Meitei traditional race competitions, winners of the race are declared only after symbolically touching the statue of the dragon "Kangla Sha". This ideology is clearly mentioned in the story of [[Khamba and Thoibi#The unfair race|the marathon competition between]] [[Khuman Khamba]] and [[Nongban]] in the epic saga of [[Khamba and Thoibi]] of [[ancient Moirang]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lipoński |first=Wojciech |url=https://archive.org/details/worldsportsencyc0000lipo?q=Kanglasha |title=World sports encyclopedia |date=2003 |publisher=St. Paul, MN : MBI |others=Internet Archive |isbn=978-0-7603-1682-5 |pages=338 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

=== Nongshāba === |

=== Nongshāba === |

||

In |

In Meitei religion mythology, [[Nongshaba]] ({{langx|mni|ꯅꯣꯡꯁꯥꯕ}}) is a Lion God and a [[king of the gods]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Neelabi |first=Sairem |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.466636/page/n155/mode/2up |title=Laiyingthou Lairemmasinggee Waree Seengbul |publisher=Longjam Arun For G.M.Publication, [[Imphal]] |year=2006 |pages=156, 157, 158, 159, 160 |language=mni |trans-title=A collection of Stories of Meetei Gods and Goddesses}}</ref><ref name="Lion">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f3AMAQAAMAAJ&q=Nongsaba |title=Internationales Asienforum: International Quarterly for Asian Studies |date=1989 |publisher=Weltform Verlag. |page=300 |language=en, de |quote=Lainingthou Nongsaba ( Lion , King of the Gods )}}</ref><ref name=moirangthem/> He produced light in the primordial universe and is often addressed as the "maker of the [[sun]]".<ref name="royal">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U14xAAAAMAAJ&q=Nongsh%C4%81ba |title=Man |date=1913 |publisher=[[Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland]] |pages=10, 81, 85 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=leach>{{Cite book |last=Leach |first=Marjorie |url=https://archive.org/details/guidetogods0000leac_k3w1/page/116/mode/2up?q=Nongshaba |title=Guide to the gods |publisher=[[Gale Research]] |year=1992 |isbn=978-1-873477-85-4 |page=116 |language=en}}</ref>{{r|hodson|p=362}} He is worshipped by the [[Meitei people]], specifically by those of the [[Ningthouja dynasty|Ningthouja clans]] as well as the [[Moilang|Moirang clans]]. He was worshipped by the [[Meitei people]] of Moirang clan as an ancestral lineage God.<ref name="Singh 2006 47, 48">{{Cite book |last=Singh |first=N. Joykumar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F1luAAAAMAAJ&q=nongshaba |title=Ethnic Relations Among the People of North-East India |date=2006 |publisher=Centre for Manipur Studies, [[Manipur University]] and Akansha Publishing House |isbn=978-81-8370-081-8 |pages=47, 48 |language=en |quote=Not only this, the deity of Lord Nongshaba was also worshipped by both communities. To the Moirangs, Nongshaba was worshipped as lineage deity and regarded as the father of Lord Thangjing.}}</ref><ref name="auto"/><ref name="parratt"/><ref name="Anthropos">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JzYoAAAAYAAJ&q=nongshaba |title=Anthropos |publisher=Zaunrith'sche Buch-, Kunst- und Steindruckerei |year=1913 |page=888 |language=en, fr, de, it |quote=Ses parents sont Nongshaba et son épouse Sarumglaima . Le premier est le plus grand des Umanglai ou dieux de la forêt ; il produisit un fils unique , Thangjing , le dieu suprême de Moirang . La manifestation de Thangjing constitue le ...}}</ref> |

||

He is the chief of all the {{langnf|mni|[[Umang Lai]]s|forest gods}} in [[Ancient Kangleipak]] (early [[Manipur]]). |

He is the chief of all the {{langnf|mni|[[Umang Lai]]s|forest gods}} in [[Ancient Kangleipak]] (early [[Manipur]]).{{r|royal|p=81}}<ref name="auto">{{Cite book |last=General |first=India Office of the Registrar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=D7TUAAAAMAAJ&q=nongshaba |title=Census of India, 1961 |date=1962 |publisher=Manager of Publications |page=53 |language=en |quote=Nongshaba and his wife Sarunglaima come in person, two by no means beautiful figures. The reason of this is that they are the parents of the Thangjing. Nongshaba is the greatest of the umang - lai or forest gods.}}</ref><ref name="parratt">{{Cite book |last=Parratt |first=Saroj Nalini |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WEQqAAAAYAAJ&q=Nongsh%C4%81ba |title=The Religion of Manipur: Beliefs, Rituals, and Historical Development |date=1980 |publisher=Firma KLM |isbn=978-0-8364-0594-1 |pages=15, 118, 125 |language=en |quote=There are two references also to Nongshāba, who, as we have seen, was the father of the Moirāng god Thāngjing.}}</ref> |

||

=== Pakhangba === |

|||

In Meitei culture, [https://medium.com/@goutamkumaroina/pakhangba-the-dragon-born-to-mother-earth-686bd76633f Pakhangba] is a very powerful dragon. He is known as a protector and ruler of the universe. He is a son to Mother Earth. Pakhangba is, no question, one of the most distinctive frightening dragons. He is known for having remote resemblances and equivalencies to Typhon of the Greeks, Bahamut of the Arabians, Nagas of the Hindus, and Quetzalcoatl of the Native Americans. His identity is the subject of numerous stories, some of which even combine him with significant historical figures.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Oinam |first=Goutamkumar |date=April 1, 2021 |title=Pakhangba — The Dragon born to Mother Earth |url=https://medium.com/@goutamkumaroina/pakhangba-the-dragon-born-to-mother-earth-686bd76633f}}</ref> |

|||

== Monkeys in Meitei culture == |

== Monkeys in Meitei culture == |

||

{{ |

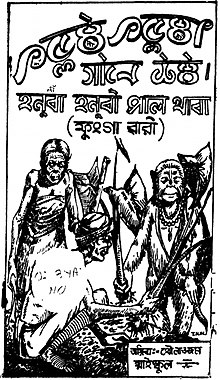

{{Further|Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba}} |

||

[[File:ꯍꯅꯨꯕ ꯍꯅꯨꯕꯤ ꯄꯥꯟ ꯊꯥꯕ.jpg|thumb |

[[File:ꯍꯅꯨꯕ ꯍꯅꯨꯕꯤ ꯄꯥꯟ ꯊꯥꯕ.jpg|thumb|An illustration of a [[Meitei folktale]] of the ''[[Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba]]'', the story of an old aged lonely couple being tricked by a group of monkeys]] |

||

The [[Meitei folktale]] of {{langnf|mni| |

The [[Meitei folktale]] of {{langnf|mni|[[Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba]]|Old Man and Old Woman planting [[Colocasia]]/[[Taro]]}}, also known as the {{lang|mni|'''[[Hanubi Hentak! Hanuba Hentak!]]'''}}, is about the story of an old couple who were tricked by a gang of monkeys.<ref name=sanatombi>{{Cite book |url= https://archive.org/details/dli.language.0065/page/n51/mode/2up |author=S. Sanatombi |script-title=mni:মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী |date=2014 |page=51 |language=mni}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HRHUDwAAQBAJ&dq=hanuba+hanubi+pan+thaba+folktale+manipur&pg=PA355 |title=Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages of India: Science History and Culture |last=Tamang |first=Jyoti Prakash |date=2020-03-02 |publisher=Springer Nature |isbn=978-981-15-1486-9 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c276DwAAQBAJ&dq=hanuba+hanubi+paan+thaaba+folktale&pg=PT271 |title=The Cultural Heritage of Manipur |last1=Meitei |first1=Sanjenbam Yaiphaba |last2=Chaudhuri |first2=Sarit K. |last3=Arunkumar |first3=M. C. |date=2020-11-25 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-29637-2 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

In the story, a childless old couple |

In the story, a childless old couple treat a group of monkeys, from the nearby forest kindly, like their own children. The monkeys give the old couple advice about planting [[taro]] in their kitchen garden. So, according to their suggestion, they boie the tubers in a pot until soft, then cooled them, wrapped them in banana leaves, and plant them in the garden. At midnight, the monkeys secretly steal and eat all the cooked taro and plant some inedible giant wild taro in their place. The next day, the old couple find the fully grown taro. They immediately cook and eat the full-grown taro and suffer an allergic reaction. Only after they take the hentak medicine is their allergy relieved. Realising they have been tricked, the old couple plan their revenge. So, the old man pretends to be dead, and the old woman cries out loudly so that the monkeys hear her. When the monkeys come and ask her what happened, she tells them that the old man died after eating the taro. She asks them to help her carry old man's body out to the lawn. As soon as the monkeys enter the housthe old man takes up his stick and beats them. Frightened, they all ran away. The old couple know that the monkeys will come back. So, they climb into the atticand hide. When the monkeys return a larger gang to take revenge, the attic breaks and falls on them, and they flee. Knowing that they might come back again, the old couple hide inside a large pot. When the monkeys come back, the couple farted continuously and the sound scares the monkeys, who flee and never return.<ref name=sharma>{{Cite book |url=http://archive.org/details/dli.language.1358/page/n55/mode/1up |title=Folktales of Manipur |last1=B. Jayantakumar Sharma |last2=Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh |date=2014 |page=51-55}}</ref><ref name=oinam>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ|title=New Folktales of Manipur |last=Oinam |first=James |date=2016-05-26 |publisher=Notion Press |isbn=978-1-945400-70-4 |pages=33–40 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

On the next day, the old couple found the fully grown taros they had planted the previous day. The two immediately cooked those full-grown taros and ate them. But as a reaction of the wild plants, the couple suffered from allergy. It was only after they ate the hentak medicine that their allergy was cured.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/dli.language.1358/page/n53/mode/1up|title=Folktales of Manipur|last1=B. Jayantakumar Sharma|last2=Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh|date=2014|page=53}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ&dq=hanube+and+hanuba&pg=PT36|title=New Folktales of Manipur|last=Oinam|first=James|date=2016-05-26|publisher=Notion Press|isbn=978-1-945400-70-4|page=36|language=en}}</ref><ref name="Oinam 37">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ&dq=hanube+and+hanuba&pg=PT37|title=New Folktales of Manipur|last=Oinam|first=James|date=2016-05-26|publisher=Notion Press|isbn=978-1-945400-70-4|page=37|language=en}}</ref> Realising the tricks of the monkey, the old couple planned to take revenge. So, the old man ({{lang-mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯍꯅꯨꯕ}}|"hanuba"}}) acted to be dead, and the old woman ({{lang-mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯍꯅꯨꯕꯤ}}|"hanubi"}}) acted to be crying out loudly to make the monkeys hear her sounds. When the monkeys came and asked her what had happened, she told them that the old man died after eating the taros.<ref name="Oinam 37"/> She asked them to help her taking the old man's body out in the lawn. All the monkeys came inside the house. As soon as they came near him, he took up his stick and bet them. Frightened, they all ran away. The old couple knew that the monkeys would surely come back.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/dli.language.1358/page/n54/mode/1up|title=Folktales of Manipur|last1=B. Jayantakumar Sharma|last2=Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh|date=2014|page=54}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ&dq=hanube+and+hanuba&pg=PT38|title=New Folktales of Manipur|last=Oinam|first=James|date=2016-05-26|publisher=Notion Press|isbn=978-1-945400-70-4|page=38|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ&dq=hanube+and+hanuba&pg=PT39|title=New Folktales of Manipur|last=Oinam|first=James|date=2016-05-26|publisher=Notion Press|isbn=978-1-945400-70-4|page=39|language=en}}</ref> So, the couple climbed up on the attic of the house and hid there. When the monkeys came back with a larger gang to take revenge, the attic broke and felt upon them. Thus, they fled from the spot. Knowing that they might come back again, the old couple hid inside a large pot. When the monkeys came back with their gangs, the couple [[fart]]ed one by one continuously and finally, the pot where they were hiding banged on unexpectedly. The loud sound of the breaking scared the monkeys who fled from the spot and never came back again.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://archive.org/details/dli.language.1358/page/n55/mode/1up|title=Folktales of Manipur|last1=B. Jayantakumar Sharma|last2=Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh|date=2014|page=55}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TpM8DAAAQBAJ&dq=hanube+and+hanuba&pg=PT40|title=New Folktales of Manipur|last=Oinam|first=James|date=2016-05-26|publisher=Notion Press|isbn=978-1-945400-70-4|page=40|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Pythons in Meitei culture == |

== Pythons in Meitei culture == |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Poubi Lai}} |

||

[[File: |

[[File:POUBI LAI.jpg|thumb|An illustration of [[Poubi Lai]] in 2015]] |

||

In Meitei mythology, '''Poubi Lai''' ({{langx|mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯄꯧꯕꯤ ꯂꯥꯏ}}|}}) was an ancient [[Pythonidae|python]]. It lived in the deep waters of the [[Loktak Lake]]. |

|||

[[File:POUBI LAI.jpg|thumb|250px|An illustration of [[Poubi Lai]] in 2015]] |

|||

<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i0ocLsvkIpIC&q=poubi+lai+mythical+serpent |title=Annual Report |last=Culture |first=India Department of |date=2002 |publisher=Department of Culture |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.dailypioneer.com/2016/editions/story-of-a-giant-poubi-lai-show-begins-on-jan-7.html |title=Story of a Giant Poubi lai |work=The Pioneer}}</ref> It is also referred to as the "[[Loch Ness Monster]] of Manipur".<ref>{{Cite magazine |url=https://www.theweek.in/leisure/society/2018/07/02/manipur-loch-ness-monster-and-other-folktales-wari-jalsa-storytelling-fest.html |title=Manipur's Loch Ness monster and other folktales at Wari-Jalsa storytelling fest |magazine=The Week}}</ref> |

|||

== Rodents in Meitei culture == |

== Rodents in Meitei culture == |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{See|Shapi Leima}} |

|||

In [[Meitei mythology]], [[Shapi Leima]] ({{langx|mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯁꯄꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ}}|}}), is one of the three favorite daughters of the sky god and mistress and the queen of all rodents.<ref name=regunathan>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xfDNm96yCPIC&q=Sabi+Leima+goddess+rodents&pg=PA70 |title=Folk Tales of the North-East |page=70|last=Regunathan |first=Sudhamahi |date=2005 |publisher=Children's Book Trust |isbn=978-81-7011-967-8 |language=en}}</ref><ref name=moirangthem>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q5eBAAAAMAAJ |title=Folk Culture of Manipur |last=Singh |first=Moirangthem Kirti |date=1993 |publisher=Manas Publications |isbn=978-81-7049-063-0 |page=11|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In [[Meitei mythology]] and [[Meitei religion|religion]], '''[[Shapi Leima]]''' ({{lang-mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯁꯄꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ}}|}}), also known as '''Shabi Leima''' ({{lang-mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯁꯕꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ}}|}}), is a goddess associated with the [[rodent]]s. She is the mistress and the queen of all the rodents living in the entire world. She is one the three favorite daughters of the sky god. Along with her two sisters, [[Khunu Leima]] and [[Nganu Leima]], she married the same man.<ref>–{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.466201/page/n39/mode/2up|title=Tal Taret|website=archive.org|year=2006|pages=39|language=mni}}<br />–{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.466201/page/n48/mode/2up|title=Tal Taret|website=archive.org|year=2006|pages=48|language=mni}}<br />–{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/dli.language.0065/page/n203/mode/2up|title=Manipuri Phungawari|website=archive.org|year=2014|pages=203|language=mni}}<br />–{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xfDNm96yCPIC&q=Sabi+Leima+goddess+rodents&pg=PA70|title=Folk Tales of the North-East|last=Regunathan|first=Sudhamahi|date=2005|publisher=Children's Book Trust|isbn=978-81-7011-967-8|language=en}}<br />–{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q5eBAAAAMAAJ&q=Sabi+(+animal+sharp+teeth+)+|title=Folk Culture of Manipur|last=Singh|first=Moirangthem Kirti|date=1993|publisher=Manas Publications|isbn=978-81-7049-063-0|language=en}}<br />–{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.467071/page/n107/mode/2up|title=Eben Mayogee Leipareng|website=archive.org|year=1995|pages=107|language=mni}}</ref> |

|||

== Tigers in Meitei culture {{anchor|Tiger in Meitei culture|Tigress in Meitei culture|Tigresses in Meitei culture}} == |

== Tigers in Meitei culture {{anchor|Tiger in Meitei culture|Tigress in Meitei culture|Tigresses in Meitei culture}} == |

||

[[File: |

[[File:The classical Meitei epic of "Khamba and Thoibi" - The tiger hunt.jpg|thumb|[[Khuman Khamba]] and his rival [[Nongban]] trying to hunt the [[Khoirentak tiger]].]] |

||

Tigers are among the most mentioned animals in different elements of |

Tigers are among the most mentioned animals in different elements of Meitei culture. |

||

=== Keibu Keioiba {{anchor|Kabui Keioiba|Tiger Head|Tiger-Head}} === |

=== Keibu Keioiba {{anchor|Kabui Keioiba|Tiger Head|Tiger-Head}} === |

||

{{Main|Keibu Keioiba|Keibu Keioiba (Tiger Head)}} |

{{Main|Keibu Keioiba|Keibu Keioiba (Tiger Head)}} |

||

In the [[Meitei mythology]] and [[Meitei folklore|folklore]], '''Keibu Keioiba''' ({{ |

In the [[Meitei mythology]] and [[Meitei folklore|folklore]], '''Keibu Keioiba''' ({{langx|mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯀꯩꯕꯨ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ}}|}}), also known as '''Kabui Keioiba''' ({{langx|mni|{{Script|Mtei|ꯀꯕꯨꯏ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ}}|}}), is a mythical creature with the head of a tiger and the body of a human. He is often described as half man and half tiger.<ref name=":ফুংগাৱারী">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.language.0065/page/n57/mode/2up |script-title=bn:মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী |last=S Sanatombi |date=2014 |page=57 |language=mni}}</ref><ref name=regunathan/><ref name=moirangthem/><ref name="Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous - Google Books">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jsRcCgAAQBAJ&dq=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger&pg=PA134 |title=Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous |last1=Devy |first1=G. N. |last2=Davis |first2=Geoffrey V. |last3=Chakravarty |first3=K. K. |date=2015-08-12 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-32569-7 |language=en |access-date=2022-06-13 |archive-date=2022-06-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220613193455/https://books.google.com/books?id=jsRcCgAAQBAJ&dq=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger&pg=PA134 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>–{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ioyfAAAAMAAJ&q=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger |title=Sangeet Natak |date=1985 |language=en |access-date=2022-06-13 |archive-date=2022-06-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220613193457/https://books.google.com/books?id=ioyfAAAAMAAJ&q=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger |url-status=live}}<br />–{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=naQYAQAAIAAJ&q=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger |title=Theatre in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology |last=Krasner |first=David |date=2008 |publisher=Wiley |isbn=978-1-4051-4043-0 |language=en |access-date=2022-06-13 |archive-date=2022-06-13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220613193529/https://books.google.com/books?id=naQYAQAAIAAJ&q=kabui+keioiba+half+man+half+tiger |url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

He was once a skilful priest named Kabui Salang Maiba. With his [[witchcraft]], he [[:wikt:transfiguration|transfigured]] himself into the form of a ferocious tiger. As a [[Divine retribution|punishment of his pride]] ([[divine retribution]]), he could not completely turn back to his original human form.<ref name="Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous - Google Books" /><ref name=":ফুংগাৱারী" /> |

He was once a skilful priest named Kabui Salang Maiba. With his [[witchcraft]], he [[:wikt:transfiguration|transfigured]] himself into the form of a ferocious tiger. As a [[Divine retribution|punishment of his pride]] ([[divine retribution]]), he could not completely turn back to his original human form.<ref name="Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous - Google Books" /><ref name=":ফুংগাৱারী" /> |

||

=== Khoirentak tiger === |

=== Khoirentak tiger === |

||

{{Main|Khoirentak tiger|Khamba and Thoibi#The tiger hunt}} |

{{Main|Khoirentak tiger|Khamba and Thoibi#The tiger hunt}} |

||

In the [[Meitei folktale]] of the [[Khamba and Thoibi]], [[Khuman Khamba]] and [[Nongban]] were in conflict regarding the affairs of princess [[Moirang Thoibi]]. Both men wanted to marry the princess. Among the two suitors, the princess had already chosen Khamba but still Nongban did not give up easily. The matter was set before the King of [[ancient Moirang]] in his court, and he ordered them to settle the matter by the [[trial by ordeal]] of the spear. However, an old woman said that there was a tiger in the forest hardby that attacked the people. So, the King chose the tiger hunt to be the witness and the ordeal. Whoever among the two that killed the tiger will get the Princess Thoibi as his wife. On the next day, the King and his ministers gathered there in stages. Many people gathered at the spot, that it seemed like a white cloth spread on the ground. Then the two went inside the forest. Near a dead body of a freshly killed girl, the tiger was found. Nongban tried to spear the tiger but he missed his target. Then the tiger sprang upon them and bit Nongban. Khamba wounded the beast, and drove it off. Then he carried Nongban to the gallery. Then Khamba entered the forest once again and found the tiger crouching in a hollow half hidden by the forest, but in full view of the gallery of the King. |

In the [[Meitei folktale]] of the [[Khamba and Thoibi]], [[Khuman Khamba]] and [[Nongban]] were in conflict regarding the affairs of princess [[Moirang Thoibi]]. Both men wanted to marry the princess. Among the two suitors, the princess had already chosen Khamba but still Nongban did not give up easily. The matter was set before the King of [[ancient Moirang]] in his court, and he ordered them to settle the matter by the [[trial by ordeal]] of the spear. However, an old woman said that there was a tiger in the forest hardby that attacked the people. So, the King chose the tiger hunt to be the witness and the ordeal. Whoever among the two that killed the tiger will get the Princess Thoibi as his wife. On the next day, the King and his ministers gathered there in stages. Many people gathered at the spot, that it seemed like a white cloth spread on the ground. Then the two went inside the forest. Near a dead body of a freshly killed girl, the tiger was found. Nongban tried to spear the tiger but he missed his target. Then the tiger sprang upon them and bit Nongban. Khamba wounded the beast, and drove it off. Then he carried Nongban to the gallery. Then Khamba entered the forest once again and found the tiger crouching in a hollow half hidden by the forest, but in full view of the gallery of the King.{{r|hodson|p=150–151}} |

||

=== Tiger of Goddess Panthoibi === |

=== Tiger of Goddess Panthoibi === |

||

{{ |

{{Further|Panthoibi|Panthoibi Khonggul}} |

||

== Tortoises and turtles in Meitei culture == |

== Tortoises and turtles in Meitei culture == |

||

[[File:Sandrembi getting panic on seeing her tortoise mother Yangkhuleima about to die.jpg|thumb |

[[File:Sandrembi getting panic on seeing her tortoise mother Yangkhuleima about to die.jpg|thumb|In the [[Meitei folktale]] of [[Sandrembi and Chaisra]], Sandrembi's mother turned into a tortoise/turtle after her death and came back to her daughter but she again fell in troubles]] |

||

=== Tortoise/Turtle in the story of Sandrembi and Chaisra === |

=== Tortoise/Turtle in the story of Sandrembi and Chaisra === |

||

In the [[Meitei folktale]] of [[Sandrembi and Chaisra]], Sandrembi's mother transformed herself into a tortoise/turtle, after some time, she was killed by Sandrembi's stepmother, who was her cowife and rival. Upon being instructed in Sandrembi's dream, Sandrembi took |

In the [[Meitei folktale]] of [[Sandrembi and Chaisra]], Sandrembi's mother transformed herself into a tortoise/turtle, after some time, she was killed by Sandrembi's stepmother, who was her cowife and rival. Upon being instructed in Sandrembi's dream, Sandrembi took the tortoise from the lake and kept it inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any break. It was told to her that her mother could re-assume her human form from the tortoise form only if kept inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any disturbance. However, before the completion of the five days, Chaisra discovered the tortoise and so, she insisted her mother to force Sandrembi to cook the tortoise meat for her. Poor Sandrembi was forced to boil her own mother in the tortoise form. Sandrembi tried to take away the fuel stick on hearing the tortoise mother's crying words of pain from the boiling pan/pot but she was forced to put the fuel in by her stepmother. Like this, Sandrembi could not save her tortoise mother from being killed.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Beck |first1=Brenda E. F. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jmKu3t-sYi4C&dq=sandrembi&pg=PA163 |title=Folktales of India |last2=Claus |first2=Peter J. |last3=Goswami |first3=Praphulladatta |last4=Handoo |first4=Jawaharlal |date=1999 |publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]] |isbn=978-0-226-04083-7 |page=163 |language=en}}</ref> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 91: | Line 102: | ||

* [[Plants in Meitei culture]] |

* [[Plants in Meitei culture]] |

||

* [[Birds in Meitei culture]] |

* [[Birds in Meitei culture]] |

||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

{{Notelist}} |

{{Notelist}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|28em}} |

||

== External links == |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

[[Category:Animals in art]] |

|||

[[Category:Animals in culture]] |

|||

[[Category:Animals in entertainment]] |

|||

[[Category:Works about animals]] |

|||

[[Category:Animals in mythology]] |

|||

[[Category:Animals in popular culture]] |

|||

[[Category:Animals in religion]] |

|||

[[Category:Meitei culture]] |

|||

[[Category:Meitei folklore]] |

|||

[[Category:Meitei literature]] |

|||

[[Category:Meitei mythology]] |

|||

[[Category:Sanamahism]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 22:27, 31 October 2024

Animals (Meitei: Saa/Shaa) have significant roles in different elements of Meitei culture, including but not limited to Meitei cuisine, Meitei dances, Meitei festivals, Meitei folklore, Meitei folktales, Meitei literature, Meitei mythology, Meitei religion, etc.

Deer in Meitei culture

[edit]

In one of the epic cycles of incarnations in Moirang, Kadeng Thangjahanba hunted and brought a lovely Sangai deer alive from a hunting ground called "Torbung Lamjao" as a gift of love for his girlfriend, Lady Tonu Laijinglembi. However, when he heard the news that his sweetheart lady married King Laijing Ningthou Punsiba of ancient Moirang, during his absence, he got extremely disappointed and sad. And so, with the painful and sad feelings, he realised and sensed the feelings of the deer for getting separated from its mate (partner). So, he released the deer in the wild of the Keibul Lamjao (modern day Keibul Lamjao National Park regions). Since then, the Sangai species started living in the Keibul Lamjao region as their natural habitat.[1][2]

Dogs in Meitei culture

[edit]Dogs are mentioned as friends or companions of human beings, in many ancient tales and texts. In many cases, when dogs died, they were given respect by performing elaborate death ceremonies, equal to that of human beings.[3]

When goddess Konthoujam Tampha Lairembi saw smokes in her native place, she was restless. She came down to earth from heaven to find out who was dead. On reaching the place, her mother told her as follows:

"O daughter of mine, none of your parents or brothers ever dies. The watchful dog of your Lord Soraren kept amidst us was fatally bitten by a snake. Only we performed its last rites."

— Konthoucham Nongkalol (Konthoujam Nonggarol)[3]

Elephants in Meitei culture

[edit]

In the Meitei epic of the Khamba and Thoibi, the crown prince Chingkhu Akhuba of ancient Moirang and Kongyamba, planned to kill to Khuman Khamba.[4] Kongyamba and his accomplices together threatened Khamba to give up Moirang Thoibi, which Khamba rejected. Then they fought, and Khamba bet all of them, and was about to kill Kongyamba, but the men that stood by, the friends of Kongyamba, dragged Khamba off, and bound him to the elephant of the crown prince, with ropes. Then they goaded the elephant, but the God Thangching stayed it so that it didn't move. Finally, Kongyamba lost patience. He pricked a spear to the elephant so that it moved in the pain. But it still didn't harm Khamba. Khamba seemed to be dead. Meanwhile, on the other hand, Goddess Panthoibi came in a dream to Thoibi and told her everything that was happening. So, Thoibi rushed to the spot and saved Khamba from the elephant torture.[4]: 147

Fishes in Meitei culture

[edit]

Horses in Meitei culture

[edit]

Lions in Meitei culture

[edit]

Kanglā Shā

[edit]In Meitei mythology and religion, Kangla Sa (Meitei for 'Beast of the Kangla'), also spelled as Kangla Sha, is a guardian dragon lion, whose appearance is described as a creature with a lion's body and a dragon's head, and two horns. Besides being sacred to the Meitei cultural heritage,[5][6] it is frequently portrayed in the royal symbol of the Meitei royalties (Ningthouja dynasty).[7] The most popular iconographic colossal statues of the "Kangla Sa" stand inside the Kangla Fort in Imphal.[8]

In Meitei traditional race competitions, winners of the race are declared only after symbolically touching the statue of the dragon "Kangla Sha". This ideology is clearly mentioned in the story of the marathon competition between Khuman Khamba and Nongban in the epic saga of Khamba and Thoibi of ancient Moirang.[9]

Nongshāba

[edit]In Meitei religion mythology, Nongshaba (Meitei: ꯅꯣꯡꯁꯥꯕ) is a Lion God and a king of the gods.[10][11][12] He produced light in the primordial universe and is often addressed as the "maker of the sun".[13][14][4]: 362 He is worshipped by the Meitei people, specifically by those of the Ningthouja clans as well as the Moirang clans. He was worshipped by the Meitei people of Moirang clan as an ancestral lineage God.[15][16][17][18] He is the chief of all the Umang Lais (Meitei for 'forest gods') in Ancient Kangleipak (early Manipur).[13]: 81 [16][17]

Pakhangba

[edit]In Meitei culture, Pakhangba is a very powerful dragon. He is known as a protector and ruler of the universe. He is a son to Mother Earth. Pakhangba is, no question, one of the most distinctive frightening dragons. He is known for having remote resemblances and equivalencies to Typhon of the Greeks, Bahamut of the Arabians, Nagas of the Hindus, and Quetzalcoatl of the Native Americans. His identity is the subject of numerous stories, some of which even combine him with significant historical figures.[19]

Monkeys in Meitei culture

[edit]

The Meitei folktale of Hanuba Hanubi Paan Thaaba (Meitei for 'Old Man and Old Woman planting Colocasia/Taro'), also known as the Hanubi Hentak! Hanuba Hentak!, is about the story of an old couple who were tricked by a gang of monkeys.[20][21][22]

In the story, a childless old couple treat a group of monkeys, from the nearby forest kindly, like their own children. The monkeys give the old couple advice about planting taro in their kitchen garden. So, according to their suggestion, they boie the tubers in a pot until soft, then cooled them, wrapped them in banana leaves, and plant them in the garden. At midnight, the monkeys secretly steal and eat all the cooked taro and plant some inedible giant wild taro in their place. The next day, the old couple find the fully grown taro. They immediately cook and eat the full-grown taro and suffer an allergic reaction. Only after they take the hentak medicine is their allergy relieved. Realising they have been tricked, the old couple plan their revenge. So, the old man pretends to be dead, and the old woman cries out loudly so that the monkeys hear her. When the monkeys come and ask her what happened, she tells them that the old man died after eating the taro. She asks them to help her carry old man's body out to the lawn. As soon as the monkeys enter the housthe old man takes up his stick and beats them. Frightened, they all ran away. The old couple know that the monkeys will come back. So, they climb into the atticand hide. When the monkeys return a larger gang to take revenge, the attic breaks and falls on them, and they flee. Knowing that they might come back again, the old couple hide inside a large pot. When the monkeys come back, the couple farted continuously and the sound scares the monkeys, who flee and never return.[23][24]

Pythons in Meitei culture

[edit]

In Meitei mythology, Poubi Lai (Meitei: ꯄꯧꯕꯤ ꯂꯥꯏ) was an ancient python. It lived in the deep waters of the Loktak Lake. [25][26] It is also referred to as the "Loch Ness Monster of Manipur".[27]

Rodents in Meitei culture

[edit]

In Meitei mythology, Shapi Leima (Meitei: ꯁꯄꯤ ꯂꯩꯃ), is one of the three favorite daughters of the sky god and mistress and the queen of all rodents.[28][12]

Tigers in Meitei culture

[edit]

Tigers are among the most mentioned animals in different elements of Meitei culture.

Keibu Keioiba

[edit]In the Meitei mythology and folklore, Keibu Keioiba (Meitei: ꯀꯩꯕꯨ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ), also known as Kabui Keioiba (Meitei: ꯀꯕꯨꯏ ꯀꯩꯑꯣꯏꯕ), is a mythical creature with the head of a tiger and the body of a human. He is often described as half man and half tiger.[29][28][12][30][31] He was once a skilful priest named Kabui Salang Maiba. With his witchcraft, he transfigured himself into the form of a ferocious tiger. As a punishment of his pride (divine retribution), he could not completely turn back to his original human form.[30][29]

Khoirentak tiger

[edit]In the Meitei folktale of the Khamba and Thoibi, Khuman Khamba and Nongban were in conflict regarding the affairs of princess Moirang Thoibi. Both men wanted to marry the princess. Among the two suitors, the princess had already chosen Khamba but still Nongban did not give up easily. The matter was set before the King of ancient Moirang in his court, and he ordered them to settle the matter by the trial by ordeal of the spear. However, an old woman said that there was a tiger in the forest hardby that attacked the people. So, the King chose the tiger hunt to be the witness and the ordeal. Whoever among the two that killed the tiger will get the Princess Thoibi as his wife. On the next day, the King and his ministers gathered there in stages. Many people gathered at the spot, that it seemed like a white cloth spread on the ground. Then the two went inside the forest. Near a dead body of a freshly killed girl, the tiger was found. Nongban tried to spear the tiger but he missed his target. Then the tiger sprang upon them and bit Nongban. Khamba wounded the beast, and drove it off. Then he carried Nongban to the gallery. Then Khamba entered the forest once again and found the tiger crouching in a hollow half hidden by the forest, but in full view of the gallery of the King.[4]: 150–151

Tiger of Goddess Panthoibi

[edit]Tortoises and turtles in Meitei culture

[edit]

Tortoise/Turtle in the story of Sandrembi and Chaisra

[edit]In the Meitei folktale of Sandrembi and Chaisra, Sandrembi's mother transformed herself into a tortoise/turtle, after some time, she was killed by Sandrembi's stepmother, who was her cowife and rival. Upon being instructed in Sandrembi's dream, Sandrembi took the tortoise from the lake and kept it inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any break. It was told to her that her mother could re-assume her human form from the tortoise form only if kept inside a pitcher for five consecutive days without any disturbance. However, before the completion of the five days, Chaisra discovered the tortoise and so, she insisted her mother to force Sandrembi to cook the tortoise meat for her. Poor Sandrembi was forced to boil her own mother in the tortoise form. Sandrembi tried to take away the fuel stick on hearing the tortoise mother's crying words of pain from the boiling pan/pot but she was forced to put the fuel in by her stepmother. Like this, Sandrembi could not save her tortoise mother from being killed.[32]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "State Animal Sangai". 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

Sangai is a glittering gem in the rich cultural heritage of Kangleipak (Manipur). It is said that a legendary hero Kadeng Thangjahanba of Moirang once captured a gravid Sangai from Torbung Lamjao for a loving gift to his beloved Tonu Laijinglembi. But as ill luck would have it, he found his beloved to be at the palace of the king as his spouse and, as such, all his hopes were shattered. In desperation, the hero released the deer free in the wild of Keibul Lamjao and from that time onwards the place became the home of Sangai.

- ^ Khaute, Lallian Mang (2010). The Sangai: The Pride of Manipur. Gyan Publishing House. p. 55. ISBN 978-81-7835-772-0.

- ^ a b Singh, Ch Manihar (1996). A History of Manipuri Literature (in English and Manipuri). Sahitya Akademi. p. 201. ISBN 978-81-260-0086-9.

- ^ a b c d T.C. Hodson (1908). The Meitheis. London: David Nutt. p. 146.

- ^ Chakravarti, Sudeep (6 January 2022). The Eastern Gate: War and Peace in Nagaland, Manipur and India's Far East. Simon and Schuster. p. 254. ISBN 978-93-92099-26-7.

- ^ Session, North East India History Association (1990). Proceedings of North East India History Association. Original from:the University of Michigan. The Association. pp. 133, 134.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Rituparna (29 July 2022). Northeast India Through the Ages: A Transdisciplinary Perspective on Prehistory, History, and Oral History. Taylor & Francis. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-000-62390-1.

- ^ Singh, N. Joykumar (2002). Colonialism to Democracy: A History of Manipur, 1819-1972. Original from : the University of Michigan. Spectrum Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-87502-44-9.

The construction of ' Kangla Sa ' (Lion like animal) at the front of the gate of Kangla was a great achievement of his beautification programme.

- ^ Lipoński, Wojciech (2003). World sports encyclopedia. Internet Archive. St. Paul, MN : MBI. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-7603-1682-5.

- ^ Neelabi, Sairem (2006). Laiyingthou Lairemmasinggee Waree Seengbul [A collection of Stories of Meetei Gods and Goddesses] (in Manipuri). Longjam Arun For G.M.Publication, Imphal. pp. 156, 157, 158, 159, 160.

- ^ Internationales Asienforum: International Quarterly for Asian Studies (in English and German). Weltform Verlag. 1989. p. 300.

Lainingthou Nongsaba ( Lion , King of the Gods )

- ^ a b c Singh, Moirangthem Kirti (1993). Folk Culture of Manipur. Manas Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-7049-063-0.

- ^ a b Man. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 1913. pp. 10, 81, 85.

- ^ Leach, Marjorie (1992). Guide to the gods. Gale Research. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-873477-85-4.

- ^ Singh, N. Joykumar (2006). Ethnic Relations Among the People of North-East India. Centre for Manipur Studies, Manipur University and Akansha Publishing House. pp. 47, 48. ISBN 978-81-8370-081-8.

Not only this, the deity of Lord Nongshaba was also worshipped by both communities. To the Moirangs, Nongshaba was worshipped as lineage deity and regarded as the father of Lord Thangjing.

- ^ a b General, India Office of the Registrar (1962). Census of India, 1961. Manager of Publications. p. 53.

Nongshaba and his wife Sarunglaima come in person, two by no means beautiful figures. The reason of this is that they are the parents of the Thangjing. Nongshaba is the greatest of the umang - lai or forest gods.

- ^ a b Parratt, Saroj Nalini (1980). The Religion of Manipur: Beliefs, Rituals, and Historical Development. Firma KLM. pp. 15, 118, 125. ISBN 978-0-8364-0594-1.

There are two references also to Nongshāba, who, as we have seen, was the father of the Moirāng god Thāngjing.

- ^ Anthropos (in English, French, German, and Italian). Zaunrith'sche Buch-, Kunst- und Steindruckerei. 1913. p. 888.

Ses parents sont Nongshaba et son épouse Sarumglaima . Le premier est le plus grand des Umanglai ou dieux de la forêt ; il produisit un fils unique , Thangjing , le dieu suprême de Moirang . La manifestation de Thangjing constitue le ...

- ^ Oinam, Goutamkumar (1 April 2021). "Pakhangba — The Dragon born to Mother Earth".

- ^ S. Sanatombi (2014). মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী (in Manipuri). p. 51.

- ^ Tamang, Jyoti Prakash (2 March 2020). Ethnic Fermented Foods and Beverages of India: Science History and Culture. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-15-1486-9.

- ^ Meitei, Sanjenbam Yaiphaba; Chaudhuri, Sarit K.; Arunkumar, M. C. (25 November 2020). The Cultural Heritage of Manipur. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-29637-2.

- ^ B. Jayantakumar Sharma; Dr. Chirom Rajketan Singh (2014). Folktales of Manipur. p. 51-55.

- ^ Oinam, James (26 May 2016). New Folktales of Manipur. Notion Press. pp. 33–40. ISBN 978-1-945400-70-4.

- ^ Culture, India Department of (2002). Annual Report. Department of Culture.

- ^ "Story of a Giant Poubi lai". The Pioneer.

- ^ "Manipur's Loch Ness monster and other folktales at Wari-Jalsa storytelling fest". The Week.

- ^ a b Regunathan, Sudhamahi (2005). Folk Tales of the North-East. Children's Book Trust. p. 70. ISBN 978-81-7011-967-8.

- ^ a b S Sanatombi (2014). মণিপুরী ফুংগাৱারী (in Manipuri). p. 57.

- ^ a b Devy, G. N.; Davis, Geoffrey V.; Chakravarty, K. K. (12 August 2015). Knowing Differently: The Challenge of the Indigenous. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-32569-7. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ –Sangeet Natak. 1985. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

–Krasner, David (2008). Theatre in Theory 1900-2000: An Anthology. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-4043-0. Archived from the original on 13 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022. - ^ Beck, Brenda E. F.; Claus, Peter J.; Goswami, Praphulladatta; Handoo, Jawaharlal (1999). Folktales of India. University of Chicago Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-226-04083-7.