Modal frame: Difference between revisions

m →top: Comment out vorbis=1, phab:T257066 per request, replaced: vorbis=1 → %vorbis=1%%T257066% |

→Example: Replace very low resolution image with score. |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Redirect|Focus (music)|other uses|Focus (disambiguation)#Music}} |

{{Redirect|Focus (music)|other uses|Focus (disambiguation)#Music}} |

||

A '''modal frame''' in [[music]]<ref>{{cite book |

A '''modal frame''' in [[music]]<ref>{{cite book|title=Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music|last=van der Merwe|first=Peter|author-link=Peter van der Merwe (musicologist)|year=1989|publisher=Clarendon Press|location=Oxford|isbn=0-19-316121-4|pages=[https://archive.org/details/originsofpopular0000vand/page/102 102–103]|url=https://archive.org/details/originsofpopular0000vand/page/102}}</ref> is "a number of types permeating and unifying [[Music of Africa|African]], [[Music of Europe|European]], and [[Music of the United States|American]] [[song]]" and [[melody]].<ref name="Middleton">{{harvnb|van der Merwe|1989}}, quoted in Richard Middleton (1990/2002). ''Studying Popular Music'', p. 203. Philadelphia: Open University Press. {{ISBN|0-335-15275-9}}.</ref> It may also be called a '''melodic mode.''' "Mode" and "frame" are used interchangeably in this context without reference to scalar or rhythmic modes. Melodic modes define and generate melodies that are not determined by [[harmony]], but purely by [[melody]]. A '''note frame,''' is a melodic mode that is [[Atonality|atonic]] (without a [[tonic (music)|tonic]]), or has an unstable tonic. |

||

Modal frames may be defined by their: |

Modal frames may be defined by their: |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

*'''ceiling note''': the top of the frame, |

*'''ceiling note''': the top of the frame, |

||

*'''central note''': the center around which other notes cluster or gravitate, |

*'''central note''': the center around which other notes cluster or gravitate, |

||

*'''upper''' or '''lower focus''':<ref>adapted from Ekueme, Lazarus. cited in Middleton (1990), p.203.</ref> portion of the mode on which the melody temporarily dwells, and can also defined by melody types, such as: |

*'''upper''' or '''lower focus''':<ref>adapted from Ekueme, Lazarus. cited in Middleton (1990), p. 203.</ref> portion of the mode on which the melody temporarily dwells, and can also defined by melody types, such as: |

||

**'''[[chant]] tunes''': ([[Bob Dylan]]'s "[[Subterranean Homesick Blues]]")<ref name="Middleton"/> |

**'''[[chant]] tunes''': ([[Bob Dylan]]'s "[[Subterranean Homesick Blues]]")<ref name="Middleton"/> |

||

**'''axial tunes''': ("A Hard Day's Night", "[[Peggy Sue (song)|Peggy Sue]]", [[Marvin Gaye]]'s "[[Can I Get a Witness|Can I Get A Witness]]", and [[Roy Milton]]'s "[[The Hucklebuck|Do the Hucklebuck]]")<ref name="Middleton"/> |

**'''axial tunes''': ("A Hard Day's Night", "[[Peggy Sue (song)|Peggy Sue]]", [[Marvin Gaye]]'s "[[Can I Get a Witness|Can I Get A Witness]]", and [[Roy Milton]]'s "[[The Hucklebuck|Do the Hucklebuck]]")<ref name="Middleton"/> |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

**'''[[#Ladder of thirds|ladder of thirds]]''' |

**'''[[#Ladder of thirds|ladder of thirds]]''' |

||

<score |

<score sound=1>\relative c'' { \repeat volta 1 { \time 2/2 \tempo 2 = 60 \set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t c2 a ^"↓" c a ^"↓"} } \addlyrics { Chel -- sea Chel -- sea } </score> |

||

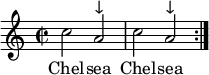

"Chel-sea" football crowd [[chant]]: minor third. |

"Chel-sea" football crowd [[chant]]: minor third. |

||

Further defined features include: |

Further defined features include: |

||

*'''melodic dissonance''': the quality of a note that is modally unstable and attracted to other more important tones in a non-harmonic way |

*'''melodic dissonance''': the quality of a note that is modally unstable and attracted to other more important tones in a non-harmonic way |

||

*'''melodic triad'''{{anchor|Melodic triad}}: arpeggiated triads in a melody. A '''non-harmonic arpeggio''' is most commonly a melodic triad, it is an [[arpeggio]] the [[note (music)|notes]] of which do not appear in the [[harmony]] of the [[accompaniment]]. |

*'''melodic triad'''{{anchor|Melodic triad}}: arpeggiated triads in a melody. A '''non-harmonic arpeggio''' is most commonly a melodic triad, it is an [[arpeggio]] the [[note (music)|notes]] of which do not appear in the [[harmony]] of the [[accompaniment]].{{sfn|van der Merwe|1989|p=321}} |

||

*[[level (music)|level]]: a temporary modal frame contrasted with another built on a different [[foundation note]]. A change in levels is called a [[level (music)|shift]]. |

*[[level (music)|level]]: a temporary modal frame contrasted with another built on a different [[foundation note]]. A change in levels is called a [[level (music)|shift]]. |

||

*'''co-tonic''': a melodic tonic different from and as important as the harmonic tonic |

*'''co-tonic''': a melodic tonic different from and as important as the harmonic tonic |

||

*'''secondary tonic''': a melodic tonic different from but subordinate to the harmonic tonic |

*'''secondary tonic''': a melodic tonic different from but subordinate to the harmonic tonic |

||

*'''pendular third''':<ref>adapted from Nketia, J.H. cited in Middleton (1990), p.203.</ref> alternating notes a third apart, most often a [[neutral third|neutral]], see [[double tonic]] |

*'''pendular third''':<ref>adapted from Nketia, J. H. cited in Middleton (1990), p. 203.</ref> alternating notes a third apart, most often a [[neutral third|neutral]], see [[double tonic]] |

||

==Shout-and-fall== |

==Shout-and-fall== |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

"Gesturally, it suggests 'affective outpouring', 'self-offering of the body', 'emptying and relaxation'." The frame may be thought of as a [[deep structure]] common to the varied surface structures of songs in which it occurs.<ref name="Middleton S&f"/> |

"Gesturally, it suggests 'affective outpouring', 'self-offering of the body', 'emptying and relaxation'." The frame may be thought of as a [[deep structure]] common to the varied surface structures of songs in which it occurs.<ref name="Middleton S&f"/> |

||

[[ |

[[File:Shout-and-Fall example.PNG|thumb|center|upright=2|Shout-and-fall example.<ref name="Middleton S&f"/>[[File:Shout-and-Fall example.mid]]]] |

||

==Ladder of thirds== |

==Ladder of thirds== |

||

[[ |

[[File:Thirteenth chord inversions.png|thumb|[[thirteenth|CM13]], [[first inversion]] = e13({{music|b}}9), [[second inversion]] = G13... Eventually seven chords along a ladder of thirds.[[File:Thirteenth chord inversions.mid]]]] |

||

A '''ladder of thirds''' (coined by |

A '''ladder of thirds''' (coined by [[Peter van der Merwe (musicologist)|van der Merwe]] 1989,{{sfn|van der Merwe|1989|pages=120ff}} adapted from [[Curt Sachs]]) is similar to the [[circle of fifths]], though a ladder of thirds differs in being composed of thirds, [[major third|major]] or [[minor third|minor]], and may or may not circle back to its starting note and thus may or may not be an [[interval cycle]]. |

||

[[Triadic chord]]s may be considered as part of a ladder of thirds. |

[[Triadic chord]]s may be considered as part of a ladder of thirds. |

||

It is a modal frame found in [[Blues]] and [[Music of the United Kingdom|British folk music]]. Though a [[pentatonic]] scale is often analyzed as a portion of the circle of fifths, the [[blues scale]] and [[melody|melodies]] in that scale come |

It is a modal frame found in [[Blues]] and [[Music of the United Kingdom|British folk music]]. Though a [[pentatonic]] scale is often analyzed as a portion of the circle of fifths, the [[blues scale]] and [[melody|melodies]] in that scale come "into being through piling up thirds below and/or above a [[Tonic (music)|tonic]] or central note."<ref name="Ladder">[[Richard Middleton (musicologist)|Middleton, Richard]] (1990). ''Studying Popular Music'', p. 203. Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0-335-15275-9}}.</ref><ref>van der Merwe (1989), p. 125.</ref><ref>Hein, Ethan (2014). "[https://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2014/blues-tonality/ Blues tonality]", ''The Ethan Hein Blog''. Accessed: 14 August 2019.</ref> |

||

They are "commonplace in post-rock 'n' roll popular music – and also appear in earlier tunes".<ref name="Ladder"/> Examples include [[The Beatles]]' "[[A Hard Day's Night (song)|A Hard Day's Night]]", [[Buddy Holly]]'s "[[Peggy Sue (song)|Peggy Sue]]" and [[The Who]]'s "[[My Generation]]", [[Ben Harney]]'s "You've Been A Good Old Wagon" (1895) and [[Ben Bernie]] et al.'s "[[Sweet Georgia Brown]]" (1925). |

They are "commonplace in post-rock 'n' roll popular music – and also appear in earlier tunes".<ref name="Ladder"/> Examples include [[The Beatles]]' "[[A Hard Day's Night (song)|A Hard Day's Night]]", [[Buddy Holly]]'s "[[Peggy Sue (song)|Peggy Sue]]" and [[The Who]]'s "[[My Generation]]", [[Ben Harney]]'s "You've Been A Good Old Wagon" (1895) and [[Ben Bernie]] et al.'s "[[Sweet Georgia Brown]]" (1925). |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

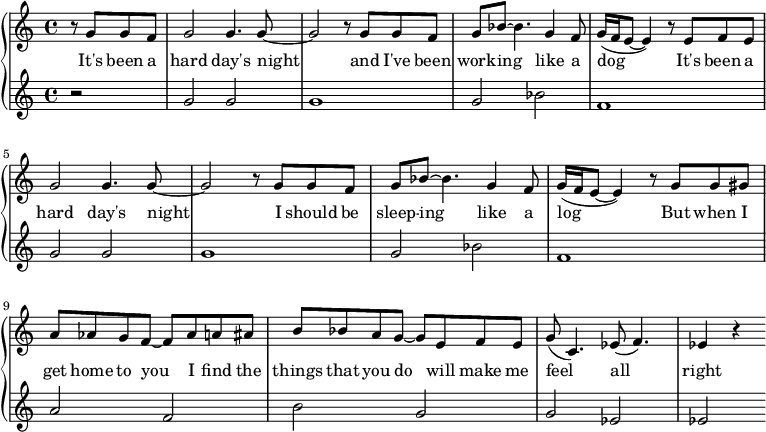

The modal frame of [[The Beatles]]' "[[A Hard Day's Night (song)|A Hard Day's Night]]" features a ladder of thirds axially centered on G with a ceiling note of B{{music|flat}} and floor note of E[{{music|flat}}] (the low C being a [[passing tone]]):<ref name="Middleton"/> |

The modal frame of [[The Beatles]]' "[[A Hard Day's Night (song)|A Hard Day's Night]]" features a ladder of thirds axially centered on G with a ceiling note of B{{music|flat}} and floor note of E[{{music|flat}}] (the low C being a [[passing tone]]):<ref name="Middleton"/> |

||

{{Image frame|content=<score> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

\new PianoStaff << |

|||

\new Staff \fixed c' { |

|||

\partial 2 r8 g g f | |

|||

g2 4. 8~ | 2 r8 g g f g bes~ 4. g4 f8 | g16( f e8~ 4) r8 e f e | \break |

|||

g2 4. 8~ | 2 r8 g g f g bes~ 4. g4 f8 | g16( f e8~ 4) r8 g g gis | \break |

|||

a aes g f~ 8 aes a ais | b bes a g~ 8 e f e | g( c4.) ees8( f4.) | ees4 r |

|||

} |

|||

\addlyrics { |

|||

It's been a hard day's night and I've been work -- ing like a dog It's been a |

|||

hard day's night I should be sleep -- ing like a log But when I |

|||

get home to you I find the things that you do will make me feel all right |

|||

} |

|||

\new Staff \fixed c' { |

|||

\partial 2 r2 | |

|||

g2 g | g1 | g2 bes | f1 | |

|||

g2 g | g1 | g2 bes | f1 | |

|||

a2 f | b g | g ees | ees |

|||

} |

|||

>> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

According to [[Richard Middleton (musicologist)|Middleton]], the song, "at first glance major-key-with-modal-touches", reveals through its "Line of Latent Mode" "a deep kinship with typical [[blues]] melodic structures: it is centred on three of the notes of the minor-[[pentatonic scale|pentatonic]] mode [on C: C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat] (E{{music|flat}}-G-B{{music|flat}}), with the contradictory major seventh (B{{music|natural}}) set against that. Moreover, the ''shape'' assumed by these notes – the modal ''frame'' – as well as the abstract scale they represent, is revealed, too; and this – an initial, repeated circling round the dominant (G), with an excursion to its minor third (B{{music|flat}}), 'answered' by a fall to the 'symmetrical' minor third of the tonic (E{{music|flat}}) – is a common pattern in blues."<ref>Middleton (1990), p.201.</ref> |

According to [[Richard Middleton (musicologist)|Middleton]], the song, "at first glance major-key-with-modal-touches", reveals through its "Line of Latent Mode" "a deep kinship with typical [[blues]] melodic structures: it is centred on three of the notes of the minor-[[pentatonic scale|pentatonic]] mode [on C: C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat] (E{{music|flat}}-G-B{{music|flat}}), with the contradictory major seventh (B{{music|natural}}) set against that. Moreover, the ''shape'' assumed by these notes – the modal ''frame'' – as well as the abstract scale they represent, is revealed, too; and this – an initial, repeated circling round the dominant (G), with an excursion to its minor third (B{{music|flat}}), 'answered' by a fall to the 'symmetrical' minor third of the tonic (E{{music|flat}}) – is a common pattern in blues."<ref>Middleton (1990), p. 201.</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 60: | Line 80: | ||

*[[Tune-family]] |

*[[Tune-family]] |

||

== |

==References== |

||

<references/> |

<references/> |

||

Latest revision as of 20:39, 7 November 2024

A modal frame in music[1] is "a number of types permeating and unifying African, European, and American song" and melody.[2] It may also be called a melodic mode. "Mode" and "frame" are used interchangeably in this context without reference to scalar or rhythmic modes. Melodic modes define and generate melodies that are not determined by harmony, but purely by melody. A note frame, is a melodic mode that is atonic (without a tonic), or has an unstable tonic.

Modal frames may be defined by their:

- floor note: the bottom of the frame, felt to be the lowest note, though isolated notes may go lower,

- ceiling note: the top of the frame,

- central note: the center around which other notes cluster or gravitate,

- upper or lower focus:[3] portion of the mode on which the melody temporarily dwells, and can also defined by melody types, such as:

- chant tunes: (Bob Dylan's "Subterranean Homesick Blues")[2]

- axial tunes: ("A Hard Day's Night", "Peggy Sue", Marvin Gaye's "Can I Get A Witness", and Roy Milton's "Do the Hucklebuck")[2]

- oscillating: (Rolling Stones' "Jumpin' Jack Flash")[2]

- open/closed: (Bo Diddley's "Hey Bo Diddley")[2]

- terrace

- shout-and-fall

- ladder of thirds

"Chel-sea" football crowd chant: minor third.

Further defined features include:

- melodic dissonance: the quality of a note that is modally unstable and attracted to other more important tones in a non-harmonic way

- melodic triad: arpeggiated triads in a melody. A non-harmonic arpeggio is most commonly a melodic triad, it is an arpeggio the notes of which do not appear in the harmony of the accompaniment.[4]

- level: a temporary modal frame contrasted with another built on a different foundation note. A change in levels is called a shift.

- co-tonic: a melodic tonic different from and as important as the harmonic tonic

- secondary tonic: a melodic tonic different from but subordinate to the harmonic tonic

- pendular third:[5] alternating notes a third apart, most often a neutral, see double tonic

Shout-and-fall

[edit]

Shout-and-fall or tumbling strain is a modal frame, "very common in Afro-American-derived styles" and featured in songs such as "Shake, Rattle and Roll" and "My Generation".[6]

"Gesturally, it suggests 'affective outpouring', 'self-offering of the body', 'emptying and relaxation'." The frame may be thought of as a deep structure common to the varied surface structures of songs in which it occurs.[6]

Ladder of thirds

[edit]

A ladder of thirds (coined by van der Merwe 1989,[7] adapted from Curt Sachs) is similar to the circle of fifths, though a ladder of thirds differs in being composed of thirds, major or minor, and may or may not circle back to its starting note and thus may or may not be an interval cycle.

Triadic chords may be considered as part of a ladder of thirds.

It is a modal frame found in Blues and British folk music. Though a pentatonic scale is often analyzed as a portion of the circle of fifths, the blues scale and melodies in that scale come "into being through piling up thirds below and/or above a tonic or central note."[8][9][10]

They are "commonplace in post-rock 'n' roll popular music – and also appear in earlier tunes".[8] Examples include The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night", Buddy Holly's "Peggy Sue" and The Who's "My Generation", Ben Harney's "You've Been A Good Old Wagon" (1895) and Ben Bernie et al.'s "Sweet Georgia Brown" (1925).

Example

[edit]The modal frame of The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night" features a ladder of thirds axially centered on G with a ceiling note of B♭ and floor note of E[♭] (the low C being a passing tone):[2]

According to Middleton, the song, "at first glance major-key-with-modal-touches", reveals through its "Line of Latent Mode" "a deep kinship with typical blues melodic structures: it is centred on three of the notes of the minor-pentatonic mode [on C: C, E-flat, F, G, B-flat] (E♭-G-B♭), with the contradictory major seventh (B♮) set against that. Moreover, the shape assumed by these notes – the modal frame – as well as the abstract scale they represent, is revealed, too; and this – an initial, repeated circling round the dominant (G), with an excursion to its minor third (B♭), 'answered' by a fall to the 'symmetrical' minor third of the tonic (E♭) – is a common pattern in blues."[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 0-19-316121-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g van der Merwe 1989, quoted in Richard Middleton (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music, p. 203. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- ^ adapted from Ekueme, Lazarus. cited in Middleton (1990), p. 203.

- ^ van der Merwe 1989, p. 321.

- ^ adapted from Nketia, J. H. cited in Middleton (1990), p. 203.

- ^ a b c Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music, [page needed]. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- ^ van der Merwe 1989, pp. 120ff.

- ^ a b Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music, p. 203. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- ^ van der Merwe (1989), p. 125.

- ^ Hein, Ethan (2014). "Blues tonality", The Ethan Hein Blog. Accessed: 14 August 2019.

- ^ Middleton (1990), p. 201.