Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Removed parameters. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | Category:Wikipedia articles with TDVİA identifiers | via #UCB_Category 577/1468 |

|||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Ottoman composer, neyzen, poet and statesman}} |

|||

'''Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi''' ({{ |

'''Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi''' ({{langx|ota| '''کازاسکر مصطفی عزت افندی'''}}, [[Turkish language|Modern Turkish]]: ''Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi'') (alternative: Kadiasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi, Seyyid Mustafa) (b. 1801 [[Tosya]] – d. 16 November 1876 [[Istanbul]]), was an [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] composer, [[neyzen]], poet and statesman best known for his [[calligraphy]].<ref name=kalem>[http://www.kalemguzeli.net/kazasker-mustafa-izzet-efendi.html Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi]</ref><ref name=kara>{{Cite web |url=http://www.tasavvufdergisi.net/Makaleler/270357298_18.1.pdf |title=Mustafa Kara, Vefatının 130. Yılında Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi, Tasavvuf Dergisi, Sayı 8:, 2007 |access-date=2015-02-25 |archive-date=2010-05-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100526210857/http://www.tasavvufdergisi.net/Makaleler/270357298_18.1.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||

==Life and career== |

==Life and career== |

||

Mustafa Izzet Efendi, the son of Destan Agazade Mustafa Aga, was born in Tosya, near the Black Sea in 1801. His mother was of the Rûmiyya branch of the Kādiriyye order.<ref>''Islam Encyclopedia,'' [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> Following his father's death, his mother sent him to Istanbul to gain an education. He studied Islamic theology, science and music and became an accomplished ''ney'' (reed-flute) player and had a delightful singing voice.<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116</ref> |

Mustafa Izzet Efendi, the son of Destan Agazade Mustafa Aga, was born in [[Tosya]], near the [[Black Sea]] in 1801. His mother was of the Rûmiyya branch of the Kādiriyye order.<ref>''Islam Encyclopedia,'' [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> Following his father's death, his mother sent him to Istanbul to gain an education. He studied Islamic theology, science and music and became an accomplished ''ney'' (reed-flute) player and had a delightful singing voice.<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116</ref> |

||

He was initially attached as an apprentice at the mausoleum of Ali-Pasha in the time of [[Mahmud II|Sultan Mahmud II]]. Later he served at the Imperial court where he learned ''[[Thuluth|sülüs]]'' and ''[[Naskh (script)| |

He was initially attached as an apprentice at the mausoleum of Ali-Pasha in the time of [[Mahmud II|Sultan Mahmud II]]. Later he served at the Imperial court where he learned ''[[Thuluth|sülüs]]'' and ''[[Naskh (script)|naskh]]'' scripts. He was certified by Moustafa Wâsif.<ref>Huart, C., ''Les Calligraphes et les Miniaturistes de l'Orient Musulman'', 1972, p. 200 [https://archive.org/details/lescalligraphes00huargoog Digital copy (in French)]</ref> He spent three years at the Sultan's court, but found court life too restrictive. He sought the Sultan's permission to make a pilgrimage to Mecca, after which he decided not to return to the Imperial Palace. Instead, he remained in Cairo before finally returning to Istanbul. He purchased a house in the Bath-house district and lived a [[Sufi]] way of life, away from the Palace.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> However, he failed to inform the Sultan of his return and did go back to the Imperial Court. |

||

Some time later, the Sultan discovered, quite by chance, that Izzet was back in Istanbul. During Ramadan, 1832, the Sultan attended prayers at the [[Bayezid II Mosque, Istanbul|Beyazid Mosque]]. When he heard a beautiful singing voice, the Sultan immediately recognised it as belonging to Mustafa Izzet Efendi.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> Disappointed that Izzet had not announced his return to Istanbul, the Sultan ordered that Izzet be punished, but eventually pardoned him. Izzet went onto occupy judicial and religious posts in the court of [[Abdulmejid I]].<ref>His title, [[Kazasker]], literally means that he was a member of the judiciary.</ref> |

Some time later, the Sultan discovered, quite by chance, that Izzet was back in Istanbul. During Ramadan, 1832, the Sultan attended prayers at the [[Bayezid II Mosque, Istanbul|Beyazid Mosque]]. When he heard a beautiful singing voice, the Sultan immediately recognised it as belonging to Mustafa Izzet Efendi.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> Disappointed that Izzet had not announced his return to Istanbul, the Sultan ordered that Izzet be punished, but eventually pardoned him. Izzet went onto occupy judicial and religious posts in the court of [[Abdulmejid I]].<ref>His title, [[Kazasker]], literally means that he was a member of the judiciary.</ref> |

||

| Line 10: | Line 11: | ||

In 1839, he became a preacher at the [[Eyüp Sultan Mosque]], which was regarded as an important duty in the period. In 1845, Sultan Abdülmecid heard Mustafa İzzet's sermon while visiting the mosque and made him the second imam.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> In 1850, he was appointed as the calligraphy master to the royal princes.<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116</ref> |

In 1839, he became a preacher at the [[Eyüp Sultan Mosque]], which was regarded as an important duty in the period. In 1845, Sultan Abdülmecid heard Mustafa İzzet's sermon while visiting the mosque and made him the second imam.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> In 1850, he was appointed as the calligraphy master to the royal princes.<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116</ref> |

||

His major contribution to Ottoman calligraphy was to develop refined versions of ''[[Thuluth|sülüs]]'' and ''[[Naskh (script)| |

His major contribution to Ottoman calligraphy was to develop refined versions of ''[[Thuluth|sülüs]]'' and ''[[Naskh (script)|naskh]]'' scripts, based on the earlier work of [[Hâfiz Osman]], [[Mahmud Celaleddin Efendi|Celaleddin]] and [[Mustafa Râkim|Râkim]]. However, his improvements were eclipsed within a generation, by the work of [[Mehmed Şevkî Efendi|Sevki Efendi]] (1829–1887) who perfected these styles to a level that has never been surpassed.<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 19</ref> In addition, to his calligraphy, Mustafa Izzet composed many songs, both religious and non-religious.<ref>"Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], [https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/mustafa-izzet-kazasker Online:]</ref> Izzet was also a collector of manuscripts and collected a large collection. After his passing, his son Ata Bey continued to collect manuscripts. His son Ata Bey worked very hard to get his picture done, however his father opposed.<ref>{{Cite web|last=|first=|date=20 January 2021|title=Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi|url=https://www.biyografya.com/biyografi/15307|access-date=20 January 2021|website=Biografya}}</ref> |

||

His most notable calligraphic students were {{ill|Mehmet Şefik|tr|Hattat Şefik Bey}} (1818–1890);<ref>Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S. (eds), ''Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture'', Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 475</ref> Şefik Bey (1819–1880); Abdullah Zuhdi Effendi (1835–1879); Muhsinzade Abdullah Bey (1832–1899) and Hasan Riza Effendi (1849–1920).<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 118</ref> |

His most notable calligraphic students were {{ill|Mehmet Şefik|tr|Hattat Şefik Bey}} (1818–1890);<ref>Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S. (eds), ''Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture'', Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 475</ref> Şefik Bey (1819–1880); Abdullah Zuhdi Effendi (1835–1879); Muhsinzade Abdullah Bey (1832–1899) and Hasan Riza Effendi (1849–1920).<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 118</ref> |

||

==Work== |

==Work== |

||

His calligraphic inscriptions can be found inside many public buildings and mosques, including [[Hagia Sophia]], [[Hırka-i Şerif Mosque|Hırka-i Şerif]], Buyuk Kasimpaya; Kucuk Mecidiye; Sinan Pasa |

His calligraphic inscriptions can be found inside many public buildings and mosques, including [[Hagia Sophia]], [[Hırka-i Şerif Mosque|Hırka-i Şerif]], Buyuk Kasimpaya; Kucuk Mecidiye; Sinan Pasa, Yahya Effendi and the [[Washington Monument]].<ref>M. Uğur Derman, ''Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection'', N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 118 Note: Some of these inscriptions were enlarged from Izzet Effendi's original stencils.</ref> |

||

==Calligraphy== |

==Calligraphy== |

||

| Line 36: | Line 37: | ||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

[[Category:Ottoman |

[[Category:19th-century composers from the Ottoman Empire]] |

||

[[Category:Calligraphers |

[[Category:Calligraphers from the Ottoman Empire]] |

||

[[Category:1801 births]] |

[[Category:1801 births]] |

||

[[Category:1876 deaths]] |

[[Category:1876 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:19th-century artists |

[[Category:19th-century artists from the Ottoman Empire]] |

||

Latest revision as of 10:42, 11 November 2024

Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi (Ottoman Turkish: کازاسکر مصطفی عزت افندی, Modern Turkish: Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi) (alternative: Kadiasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi, Seyyid Mustafa) (b. 1801 Tosya – d. 16 November 1876 Istanbul), was an Ottoman composer, neyzen, poet and statesman best known for his calligraphy.[1][2]

Life and career

[edit]Mustafa Izzet Efendi, the son of Destan Agazade Mustafa Aga, was born in Tosya, near the Black Sea in 1801. His mother was of the Rûmiyya branch of the Kādiriyye order.[3] Following his father's death, his mother sent him to Istanbul to gain an education. He studied Islamic theology, science and music and became an accomplished ney (reed-flute) player and had a delightful singing voice.[4]

He was initially attached as an apprentice at the mausoleum of Ali-Pasha in the time of Sultan Mahmud II. Later he served at the Imperial court where he learned sülüs and naskh scripts. He was certified by Moustafa Wâsif.[5] He spent three years at the Sultan's court, but found court life too restrictive. He sought the Sultan's permission to make a pilgrimage to Mecca, after which he decided not to return to the Imperial Palace. Instead, he remained in Cairo before finally returning to Istanbul. He purchased a house in the Bath-house district and lived a Sufi way of life, away from the Palace.[6] However, he failed to inform the Sultan of his return and did go back to the Imperial Court.

Some time later, the Sultan discovered, quite by chance, that Izzet was back in Istanbul. During Ramadan, 1832, the Sultan attended prayers at the Beyazid Mosque. When he heard a beautiful singing voice, the Sultan immediately recognised it as belonging to Mustafa Izzet Efendi.[7] Disappointed that Izzet had not announced his return to Istanbul, the Sultan ordered that Izzet be punished, but eventually pardoned him. Izzet went onto occupy judicial and religious posts in the court of Abdulmejid I.[8]

In 1839, he became a preacher at the Eyüp Sultan Mosque, which was regarded as an important duty in the period. In 1845, Sultan Abdülmecid heard Mustafa İzzet's sermon while visiting the mosque and made him the second imam.[9] In 1850, he was appointed as the calligraphy master to the royal princes.[10]

His major contribution to Ottoman calligraphy was to develop refined versions of sülüs and naskh scripts, based on the earlier work of Hâfiz Osman, Celaleddin and Râkim. However, his improvements were eclipsed within a generation, by the work of Sevki Efendi (1829–1887) who perfected these styles to a level that has never been surpassed.[11] In addition, to his calligraphy, Mustafa Izzet composed many songs, both religious and non-religious.[12] Izzet was also a collector of manuscripts and collected a large collection. After his passing, his son Ata Bey continued to collect manuscripts. His son Ata Bey worked very hard to get his picture done, however his father opposed.[13]

His most notable calligraphic students were Mehmet Şefik (1818–1890);[14] Şefik Bey (1819–1880); Abdullah Zuhdi Effendi (1835–1879); Muhsinzade Abdullah Bey (1832–1899) and Hasan Riza Effendi (1849–1920).[15]

Work

[edit]His calligraphic inscriptions can be found inside many public buildings and mosques, including Hagia Sophia, Hırka-i Şerif, Buyuk Kasimpaya; Kucuk Mecidiye; Sinan Pasa, Yahya Effendi and the Washington Monument.[16]

Calligraphy

[edit]-

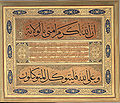

A colorful copy of the introduction to the Koran in Nastaʿlīq script

See also

[edit]- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Islamic calligraphy

- Kazasker

- List of Ottoman calligraphers

- Ottoman art

References

[edit]- ^ Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi

- ^ "Mustafa Kara, Vefatının 130. Yılında Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi, Tasavvuf Dergisi, Sayı 8:, 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-26. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- ^ Islam Encyclopedia, Online:

- ^ M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116

- ^ Huart, C., Les Calligraphes et les Miniaturistes de l'Orient Musulman, 1972, p. 200 Digital copy (in French)

- ^ "Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], Online:

- ^ "Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], Online:

- ^ His title, Kazasker, literally means that he was a member of the judiciary.

- ^ "Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], Online:

- ^ M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 116

- ^ M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 19

- ^ "Mustafa Izzet Efendi" [Biography], Online:

- ^ "Kazasker Mustafa İzzet Efendi". Biografya. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ Bloom, J. and Blair, S.S. (eds), Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 475

- ^ M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 118

- ^ M. Uğur Derman, Letters in Gold: Ottoman Calligraphy from the Sakıp Sabancı Collection, N.Y., Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998, p. 118 Note: Some of these inscriptions were enlarged from Izzet Effendi's original stencils.