P. H. McCarthy: Difference between revisions

→Career in politics: [[ ]] |

|||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

[[Category:1863 births]] |

[[Category:1863 births]] |

||

[[Category:1933 deaths]] |

[[Category:1933 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century mayors of places in California]] |

|||

[[Category:Mayors of San Francisco]] |

[[Category:Mayors of San Francisco]] |

||

[[Category:People from County Limerick]] |

[[Category:People from County Limerick]] |

||

Latest revision as of 18:07, 13 November 2024

P. H. McCarthy | |

|---|---|

| |

| 29th Mayor of San Francisco | |

| In office January 8, 1910 – January 8, 1912 | |

| Preceded by | Edward Robeson Taylor |

| Succeeded by | James Rolph Jr. |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 17, 1863 County Limerick, Ireland |

| Died | July 1, 1933 (aged 70) San Francisco |

| Political party | Union Labor Party, Republican |

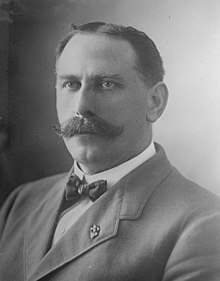

Patrick Henry McCarthy (March 17, 1863 – July 1, 1933), nicknamed "Pinhead", was an influential labor leader in San Francisco and the 29th Mayor of the City from 1910 to 1912. Born in County Limerick, Ireland, he apprenticed as a carpenter in Ireland before emigrating to the United States in 1880. He moved to San Francisco in 1886, where he rose through the ranks to become president of Carpenters Local 22, then President of the Building Trades Council in 1896. He was one the founder of the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League that 2 years later renamed into the Asiatic Exclusion League.

Leadership in the Building Trades Council

[edit]The San Francisco Building Trades Council was one of the most powerful local labor bodies within the American Federation of Labor at the time. It fought off the efforts of employers in San Francisco to impose the open shop on construction workers in the first decade of the twentieth century and was active in local politics. It also feuded with the San Francisco Labor Council, the body that claimed to represent all of organized labor in San Francisco. The BTC barred its members from belonging to the SFLC and often refused to support SFLC activities; it did not support the Teamsters and longshore workers in the City Front Federation strike of 1901, preferring to maintain its dominant position in the construction industry than join in a direct confrontation with the most powerful businesses of the region.

Within its own sphere the BTC was highly effective, coordinating the efforts of roughly fifty unions to police every construction worksite in the City to check that only union members were working there. The BTC was able to turn this control at the workplace level into better wages in the San Francisco construction industry than anywhere else in the country in the first decades of the twentieth century. The BTC was able to do this, moreover, without fighting the drawn-out battles that unions elsewhere had to wage simply to obtain recognition or preserve their rights: only two building trades strikes in San Francisco between 1901 and 1921 lasted more than a week.

The exception to that rule came in 1900, when the BTC unilaterally declared that its members would work only eight hours a day for $3 a day. When mill resisted, the BTC began organizing mill workers; the employers responded by locking out 8,000 employees throughout the Bay Area. The BTC, in return, established a union planing mill from which construction employers could obtain supplies – or face boycotts and sympathy strikes if they did not. That brought the mill owners to arbitration, where the union won the eight-hour day, a closed shop for all skilled workers, and an arbitration panel to resolve future disputes. In return, the union agreed to refuse to work with material produced by non-union planing mills or those that paid less than the Bay Area employers.

McCarthy ruled the BTC like an autocrat: he did not brook criticism, much less challenges to his authority, and he sometimes made decisions concerning local unions without consulting the parties involved. His high-handed style served him for many years, but created enough resentment within the BTC that eventually forced him to resign from its presidency in 1922, following the loss of a strike that allowed the open shop to return to San Francisco in 1921.

Career in politics

[edit]Labor unions had helped elect James D. Phelan, a Democrat, to several terms as Mayor of San Francisco. They were outraged, therefore, when Phelan sided with the employers in the City Front Federation Strike of 1901. Labor unions associated with the SFLC organized the Union Labor Party to challenge him. McCarthy and the BTC, characteristically, not only did not join in the campaign, but supported a rival candidate.

The ULP's candidate, Eugene E. Schmitz, won election in 1901. Schmitz' administration, however, was largely controlled by Abraham "Abe" Ruef, a political boss who made few efforts to conceal the depth of his corruption. Reform elements succeeded in bringing about Ruef's conviction and Schmitz' removal from office in 1907.

McCarthy was eager to fill this vacancy. While the criminal proceedings were still underway, and during the midst of a bitter strike by San Francisco streetcar workers, McCarthy ran on a platform of promising to halt the ongoing prosecutions. That put him in conflict with the SFLC, while undercutting his own reputation for honesty. McCarthy lost.

McCarthy ran again, this time successfully, in 1909. As Mayor he installed BTC officials throughout his administration, required City employees to become union members, and raised the minimum wage for city employees from $2 to $3 per day. He also required all city employees to be U.S. citizens, in line with the BTC's nativist leanings.

While McCarthy's administration was largely scandal-free, it suffered from a number of political failures, including the contentious effort to import water from the O'Shaughnessy Dam, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Hetch Hetchy Valley, in Yosemite National Park to San Francisco. Reform-minded businessmen chose James Rolph Jr., known as "Sunny Jim", to run against him. Rolph won and the ULP faded from the scene. McCarthy returned to the Republican Party, serving as a delegate to Republican National Convention in 1920.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Walter Galenson, United Brotherhood of Carpenters: the First Hundred Years. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- Michael Kazin, Barons of Labor: The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

- Robert Edward Lee Knight, Industrial Relations in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1900-1918. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1960.