Giedroyc Doctrine: Difference between revisions

Essential information in regards to Polish foreign policy |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| (10 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Political doctrine urging reconciliation among European countries}} |

|||

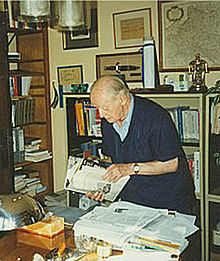

[[File:Jerzy Giedroyc 1997.jpg|thumbnail|[[Jerzy Giedroyc]] (Maisons-Laffitte, 1997)]] |

[[File:Jerzy Giedroyc 1997.jpg|thumbnail|[[Jerzy Giedroyc]] (Maisons-Laffitte, 1997)]] |

||

The '''Giedroyc doctrine''' ({{IPA |

The '''Giedroyc doctrine''' ({{IPA|pl|ˈɡʲɛdrɔjt͡s|pron}}; {{langx|pl|doktryna Giedroycia}}) or ''' Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine ''' was a [[political doctrine]] that urged reconciliation among [[Central and Eastern Europe]]an countries. It was developed by postwar Polish [[émigré]]s, and was named for [[Jerzy Giedroyc]], a Polish émigré publicist, with significant contributions by [[Juliusz Mieroszewski]] for whom it is also sometimes named. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Giedroyc developed the doctrine in the 1970s in the journal ''[[Kultura]]'' with [[Juliusz Mieroszewski]] (the doctrine is sometimes called the Giedroyc-Mieroszewski doctrine<ref name=lit>Živilė Dambrauskaitė, Tomas Janeliūnas, Vytis Jurkonis, Vytautas Sirijos Gira, ''[http://lfpr.lt/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/LFPR-26-Dambrauskaite-el-al.pdf Lithuanian – Polish Relations Reconsidered: A Constrained Bilateral Agenda or an Empty Strategic Partnership?]'' pp. 126–27 online, direct PDF download.</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Nazwa * |url=http://www.przeglad-tygodnik.pl/pl/artykul/do-uczniow-giedroycia |title=Do uczniów Giedroycia | Tygodnik "Przegląd" |publisher=Przeglad-tygodnik.pl |date= |accessdate=2013-03-07}}</ref>) and other émigrés of the "[[Maisons-Laffitte]] group".<ref name=lit/><ref name="Szczerbiak2012">{{cite book|author=Aleks Szczerbiak|title=Poland within the European Union: New Awkward Partner or New Heart of Europe?|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wACSxUX-wZAC&pg=PA1904|accessdate=7 March 2013|date=23 April 2012|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-134-17902-2|pages=1904–1905}}</ref><ref name=spw>Piotr A. Maciążek, [https://web.archive.org/web/20171228112314/http://politykawschodnia.pl/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/S%C5%82ownik-Polityki-Wschodniej1.pdf Słownik Polityki Wschodniej]. Polityka Wschodnia, 2011</ref><ref name=liberteworld>{{cite web|url=http://liberteworld.com/2011/03/08/the-giedroyc-era-ended-in-foreign-policy/ |title=The Giedroyc era ended in foreign policy |publisher=Liberte World |date=2011-03-08 |accessdate=2013-03-07}}</ref><ref name="Lorek2009"/> The doctrine can be traced to the interwar [[Prometheism|Prometheist]] project of [[Józef Piłsudski]].<ref name="Lorek2009">{{cite book|author=Andreas Lorek|title=Poland's Role in the Development of an 'Eastern Dimension' of the European Union|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lsmgmbbKD9MC&pg=PA23|accessdate=7 March 2013|date=February 2009|publisher=GRIN Verlag|isbn=978-3-640-25671-6|pages=23–24}}</ref> |

Giedroyc developed the doctrine in the 1970s in the journal ''[[Kultura]]'' with [[Juliusz Mieroszewski]] (the doctrine is sometimes called the Giedroyc-Mieroszewski doctrine<ref name=lit>Živilė Dambrauskaitė, Tomas Janeliūnas, Vytis Jurkonis, Vytautas Sirijos Gira, ''[http://lfpr.lt/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/LFPR-26-Dambrauskaite-el-al.pdf Lithuanian – Polish Relations Reconsidered: A Constrained Bilateral Agenda or an Empty Strategic Partnership?]'' pp. 126–27 online, direct PDF download.</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Nazwa * |url=http://www.przeglad-tygodnik.pl/pl/artykul/do-uczniow-giedroycia |title=Do uczniów Giedroycia | Tygodnik "Przegląd" |publisher=Przeglad-tygodnik.pl |date= |accessdate=2013-03-07}}</ref>) and other émigrés of the "[[Maisons-Laffitte]] group".<ref name=lit/><ref name="Szczerbiak2012">{{cite book|author=Aleks Szczerbiak|title=Poland within the European Union: New Awkward Partner or New Heart of Europe?|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wACSxUX-wZAC&pg=PA1904|accessdate=7 March 2013|date=23 April 2012|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-134-17902-2|pages=1904–1905}}</ref><ref name=spw>Piotr A. Maciążek, [https://web.archive.org/web/20171228112314/http://politykawschodnia.pl/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/S%C5%82ownik-Polityki-Wschodniej1.pdf Słownik Polityki Wschodniej]. Polityka Wschodnia, 2011</ref><ref name=liberteworld>{{cite web |url=http://liberteworld.com/2011/03/08/the-giedroyc-era-ended-in-foreign-policy/ |title=The Giedroyc era ended in foreign policy |publisher=Liberte World |date=2011-03-08 |accessdate=2013-03-07 |archive-date=2011-09-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110918095023/http://liberteworld.com/2011/03/08/the-giedroyc-era-ended-in-foreign-policy/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="Lorek2009"/> The doctrine can be traced to the interwar [[Prometheism|Prometheist]] project of [[Józef Piłsudski]].<ref name="Lorek2009">{{cite book|author=Andreas Lorek|title=Poland's Role in the Development of an 'Eastern Dimension' of the European Union|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lsmgmbbKD9MC&pg=PA23|accessdate=7 March 2013|date=February 2009|publisher=GRIN Verlag|isbn=978-3-640-25671-6|pages=23–24}}</ref> |

||

The doctrine urged the need to rebuild good relations among [[East Central Europe|East-Central]] and [[Eastern European|East European]] countries. The doctrine also claimed that the preservation of independence by the new post-Soviet states that lie between Poland and the Russian Federation is a fundamental Polish long-term interest.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wesley |first1=Michael |last2=Rodkiewicz |first2=Witold |title=Global Allies: Comparing US Alliances in the 21st Century |date=2017 |publisher=ANU Press |page=134 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1sq5twz |access-date=20 June 2022}}</ref> This called for Poland to reject any imperial ambitions and controversial territorial claims, and to accept the postwar border changes.<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=liberteworld/><ref name="Lorek2009"/> The doctrine supported independence for [[Belarus]] and [[Ukraine]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> It also advocated treating all East European countries as equal in importance to Russia, and refusing special treatment for Russia.<ref name=lit/><ref name=spw/> The doctrine was not hostile to Russia, but called on both Poland and Russia to abandon their struggle over domination of other East European countries — in this context, mainly the [[Baltic states]], Belarus, and Ukraine (hence another name for the doctrine: the "ULB doctrine", where "ULB" stands for "Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus").<ref name=lit/><ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=spw/><ref name=liberteworld/> |

The doctrine urged the need to rebuild good relations among [[East Central Europe|East-Central]] and [[Eastern European|East European]] countries. The doctrine also claimed that the preservation of independence by the new post-Soviet states that lie between Poland and the Russian Federation is a fundamental Polish long-term interest.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wesley |first1=Michael |last2=Rodkiewicz |first2=Witold |title=Global Allies: Comparing US Alliances in the 21st Century |date=2017 |publisher=ANU Press |page=134 |jstor=j.ctt1sq5twz |isbn=9781760461171 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1sq5twz |access-date=20 June 2022}}</ref> This called for Poland to reject any imperial ambitions and controversial territorial claims, and to accept the postwar border changes.<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=liberteworld/><ref name="Lorek2009"/> The doctrine supported independence for [[Belarus]] and [[Ukraine]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> It also advocated treating all East European countries as equal in importance to Russia, and refusing special treatment for Russia.<ref name=lit/><ref name=spw/> The doctrine was not hostile to Russia, but called on both Poland and Russia to abandon their struggle over domination of other East European countries — in this context, mainly the [[Baltic states]], Belarus, and Ukraine (hence another name for the doctrine: the "ULB doctrine", where "ULB" stands for "Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus").<ref name=lit/><ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=spw/><ref name=liberteworld/> |

||

Initially it was addressing the attitude of the [[post-World War II]] Polish emigres, especially around the [[Polish government-in-exile]] in London, and basically calling for the recognition of the post-war ''status quo''. <ref>[https://www.tygodnikprzeglad.pl/do-uczniow-giedroycia/ "Do uczniów Giedroycia"], ''[[Przeglad]]'', November 7, 2002</ref> Later it was adapted towards the goal of the moving of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania away from the Soviet and later Russian sphere of influence.<ref>[http://wyborcza.pl/7,75968,21216602,bialorus-dobry-sasiad-mowi-po-polsku.html "Białoruś. Dobry sąsiad mówi po polsku"], ''[[Gazeta Wyborcza]]'', January 8, 2017</ref> |

Initially it was addressing the attitude of the [[post-World War II]] Polish emigres, especially around the [[Polish government-in-exile]] in London, and basically calling for the recognition of the post-war ''status quo''. <ref>[https://www.tygodnikprzeglad.pl/do-uczniow-giedroycia/ "Do uczniów Giedroycia"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190525133058/https://www.tygodnikprzeglad.pl/do-uczniow-giedroycia/ |date=2019-05-25 }}, ''[[Przeglad]]'', November 7, 2002</ref> Later it was adapted towards the goal of the moving of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania away from the Soviet and later Russian sphere of influence.<ref>[http://wyborcza.pl/7,75968,21216602,bialorus-dobry-sasiad-mowi-po-polsku.html "Białoruś. Dobry sąsiad mówi po polsku"], ''[[Gazeta Wyborcza]]'', January 8, 2017</ref> |

||

The doctrine supported the [[European Union]] and aimed at removing East-Central and East European countries from the [[Soviet]] [[sphere of influence]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> After Poland regained its independence from Soviet influence following the [[fall of communism]] in 1989, the doctrine was implemented in Poland's Eastern foreign policies. Poland itself began integrating into the [[European Union]], eventually [[Poland and the European Union|joining the EU in 2004]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=spw/><ref name="Lorek2009"/> Poland has likewise supported Ukrainian membership in the European Union and [[NATO]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> The doctrine has resulted in some tensions in [[Polish-Russian relations]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> |

The doctrine supported the [[European Union]] and aimed at removing East-Central and East European countries from the [[Soviet]] [[sphere of influence]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> After Poland regained its independence from Soviet influence following the [[fall of communism]] in 1989, the doctrine was implemented in Poland's Eastern foreign policies. Poland itself began integrating into the [[European Union]], eventually [[Poland and the European Union|joining the EU in 2004]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/><ref name=spw/><ref name="Lorek2009"/> Poland has likewise supported Ukrainian membership in the European Union and [[NATO]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> The doctrine has resulted in some tensions in [[Polish-Russian relations]].<ref name="Szczerbiak2012"/> |

||

The doctrine has been questioned by some commentators and politicians, particularly in the 21st century,<ref name=spw/> and it has been suggested that in recent years the doctrine has been abandoned by the [[Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Poland)|Polish Foreign Ministry]].<ref name=liberteworld/> Others, however, argue that the policy remains in force and is endorsed by the Polish Foreign Ministry.<ref name=lit/><ref>[http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf "''O Giedroycia sporu nie ma. Rozmowa z Radosławem Sikorskim''"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111106055715/http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf |date=2011-11-06 }}, ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' 1/2010, pp. 69–77.</ref> |

The doctrine has been questioned by some commentators and politicians, particularly in the 21st century,<ref name=spw/> and it has been suggested that in recent years the doctrine has been abandoned by the [[Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Poland)|Polish Foreign Ministry]].<ref name=liberteworld/> Others, however, argue that the policy remains in force and is endorsed by the Polish Foreign Ministry.<ref name=lit/><ref>[http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf "''O Giedroycia sporu nie ma. Rozmowa z Radosławem Sikorskim''"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111106055715/http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf |date=2011-11-06 }}, ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' 1/2010, pp. 69–77.</ref> |

||

Pietrzak argues that "Although Giedroyć and Mieroszewski were idealistic, and they were very often criticized for the naïve character of their ideas, they were proven right, for they managed to inadvertently shape the future of the region and encourage most of the countries that border Russia to be more proactive in doing their utmost to preventing a domino effect in Eastern Europe – for Russia clearly attempted to implement a [[Munich Crisis|Sudetenland-type scenario]] in [[Russian invasion of Ukraine|Ukraine in 2022]]".<ref>Piotr Pietrzak (2023, February 3). The Giedroyć-Mieroszewski Doctrine and Poland’s Response to Russia’s Assault on Ukraine. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/02/03/the-giedroyc-mieroszewski-doctrine-and-polands-response-to-russias-assault-on-ukraine/</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 24: | Line 26: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://pulaski.pl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=342%3Ajeli-nie-ulb-to-co-doktryna-giedroycia-w-xxi-w-&catid=13%3Aprogram-wschodni&Itemid=53&lang=pl „''Jeśli nie ULB, to co? Doktryna Giedroycia w XXI w.''”] ("If Not ULB, Then What? The Giedroyc Doctrine in the 21st Century", 17 June 2010) |

*[http://pulaski.pl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=342%3Ajeli-nie-ulb-to-co-doktryna-giedroycia-w-xxi-w-&catid=13%3Aprogram-wschodni&Itemid=53&lang=pl „''Jeśli nie ULB, to co? Doktryna Giedroycia w XXI w.''”] ("If Not ULB, Then What? The Giedroyc Doctrine in the 21st Century", 17 June 2010) |

||

*Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz, [http://www.rp.pl/artykul/486685.html "''Pożegnanie z Giedroyciem''"] ("Farewell to Giedroyc", ''Rzeczpospolita'', 28-05-2010). |

*Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz, [https://archive.today/20130416110702/http://www.rp.pl/artykul/486685.html "''Pożegnanie z Giedroyciem''"] ("Farewell to Giedroyc", ''Rzeczpospolita'', 28-05-2010). |

||

*[[Zdzisław Najder]], [https://web.archive.org/web/20161114120556/http://www.new.org.pl/2010-06-10,abdoktryna_ulb_koncepcja_giedroycia_i_mieroszewskiego_w_xxi_wieku.html "'Doktryna ULB – koncepcja Giedroycia i Mieroszewskiego w XXI wieku''"] ("The ULB Doctrine: Giedroyc's and Mieroszewski's Concept in the 21st century"). [https://web.archive.org/web/20160304003017/http://www.new.org.pl/2010-07-02,zndoktryna_ulb_koncepcja_giedroycia_i_mieroszewskiego_w_xxi_wieku.html]. |

*[[Zdzisław Najder]], [https://web.archive.org/web/20161114120556/http://www.new.org.pl/2010-06-10,abdoktryna_ulb_koncepcja_giedroycia_i_mieroszewskiego_w_xxi_wieku.html "'Doktryna ULB – koncepcja Giedroycia i Mieroszewskiego w XXI wieku''"] ("The ULB Doctrine: Giedroyc's and Mieroszewski's Concept in the 21st century"). [https://web.archive.org/web/20160304003017/http://www.new.org.pl/2010-07-02,zndoktryna_ulb_koncepcja_giedroycia_i_mieroszewskiego_w_xxi_wieku.html]. |

||

*Marcin Wojciechowski, [https://web.archive.org/web/20111106055715/http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf "''Co po Giedroyciu? Giedroyc!''"] ("What Comes after Giedroyc? Giedroyc!"), ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' (New Eastern Europe), 1/2010, pp. 69–77. |

*Marcin Wojciechowski, [https://web.archive.org/web/20111106055715/http://www.new.org.pl/files/docs/new110.pdf "''Co po Giedroyciu? Giedroyc!''"] ("What Comes after Giedroyc? Giedroyc!"), ''Nowa Europa Wschodnia'' (New Eastern Europe), 1/2010, pp. 69–77. |

||

[[Category:Foreign relations of |

[[Category:Foreign relations of the Second Polish Republic]] |

||

[[Category:Polish People's Republic]] |

[[Category:Polish People's Republic]] |

||

[[Category:History of Poland (1989–present)]] |

[[Category:History of Poland (1989–present)]] |

||

Latest revision as of 17:51, 16 November 2024

The Giedroyc doctrine (pronounced [ˈɡʲɛdrɔjt͡s]; Polish: doktryna Giedroycia) or Giedroyc–Mieroszewski doctrine was a political doctrine that urged reconciliation among Central and Eastern European countries. It was developed by postwar Polish émigrés, and was named for Jerzy Giedroyc, a Polish émigré publicist, with significant contributions by Juliusz Mieroszewski for whom it is also sometimes named.

History

[edit]Giedroyc developed the doctrine in the 1970s in the journal Kultura with Juliusz Mieroszewski (the doctrine is sometimes called the Giedroyc-Mieroszewski doctrine[1][2]) and other émigrés of the "Maisons-Laffitte group".[1][3][4][5][6] The doctrine can be traced to the interwar Prometheist project of Józef Piłsudski.[6]

The doctrine urged the need to rebuild good relations among East-Central and East European countries. The doctrine also claimed that the preservation of independence by the new post-Soviet states that lie between Poland and the Russian Federation is a fundamental Polish long-term interest.[7] This called for Poland to reject any imperial ambitions and controversial territorial claims, and to accept the postwar border changes.[3][5][6] The doctrine supported independence for Belarus and Ukraine.[3] It also advocated treating all East European countries as equal in importance to Russia, and refusing special treatment for Russia.[1][4] The doctrine was not hostile to Russia, but called on both Poland and Russia to abandon their struggle over domination of other East European countries — in this context, mainly the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine (hence another name for the doctrine: the "ULB doctrine", where "ULB" stands for "Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus").[1][3][4][5]

Initially it was addressing the attitude of the post-World War II Polish emigres, especially around the Polish government-in-exile in London, and basically calling for the recognition of the post-war status quo. [8] Later it was adapted towards the goal of the moving of Belarus, Ukraine and Lithuania away from the Soviet and later Russian sphere of influence.[9]

The doctrine supported the European Union and aimed at removing East-Central and East European countries from the Soviet sphere of influence.[3] After Poland regained its independence from Soviet influence following the fall of communism in 1989, the doctrine was implemented in Poland's Eastern foreign policies. Poland itself began integrating into the European Union, eventually joining the EU in 2004.[3][4][6] Poland has likewise supported Ukrainian membership in the European Union and NATO.[3] The doctrine has resulted in some tensions in Polish-Russian relations.[3]

The doctrine has been questioned by some commentators and politicians, particularly in the 21st century,[4] and it has been suggested that in recent years the doctrine has been abandoned by the Polish Foreign Ministry.[5] Others, however, argue that the policy remains in force and is endorsed by the Polish Foreign Ministry.[1][10] Pietrzak argues that "Although Giedroyć and Mieroszewski were idealistic, and they were very often criticized for the naïve character of their ideas, they were proven right, for they managed to inadvertently shape the future of the region and encourage most of the countries that border Russia to be more proactive in doing their utmost to preventing a domino effect in Eastern Europe – for Russia clearly attempted to implement a Sudetenland-type scenario in Ukraine in 2022".[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Živilė Dambrauskaitė, Tomas Janeliūnas, Vytis Jurkonis, Vytautas Sirijos Gira, Lithuanian – Polish Relations Reconsidered: A Constrained Bilateral Agenda or an Empty Strategic Partnership? pp. 126–27 online, direct PDF download.

- ^ Nazwa *. "Do uczniów Giedroycia | Tygodnik "Przegląd"". Przeglad-tygodnik.pl. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Aleks Szczerbiak (23 April 2012). Poland within the European Union: New Awkward Partner or New Heart of Europe?. CRC Press. pp. 1904–1905. ISBN 978-1-134-17902-2. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Piotr A. Maciążek, Słownik Polityki Wschodniej. Polityka Wschodnia, 2011

- ^ a b c d "The Giedroyc era ended in foreign policy". Liberte World. 2011-03-08. Archived from the original on 2011-09-18. Retrieved 2013-03-07.

- ^ a b c d Andreas Lorek (February 2009). Poland's Role in the Development of an 'Eastern Dimension' of the European Union. GRIN Verlag. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-3-640-25671-6. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ Wesley, Michael; Rodkiewicz, Witold (2017). Global Allies: Comparing US Alliances in the 21st Century. ANU Press. p. 134. ISBN 9781760461171. JSTOR j.ctt1sq5twz. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ "Do uczniów Giedroycia" Archived 2019-05-25 at the Wayback Machine, Przeglad, November 7, 2002

- ^ "Białoruś. Dobry sąsiad mówi po polsku", Gazeta Wyborcza, January 8, 2017

- ^ "O Giedroycia sporu nie ma. Rozmowa z Radosławem Sikorskim" Archived 2011-11-06 at the Wayback Machine, Nowa Europa Wschodnia 1/2010, pp. 69–77.

- ^ Piotr Pietrzak (2023, February 3). The Giedroyć-Mieroszewski Doctrine and Poland’s Response to Russia’s Assault on Ukraine. Modern Diplomacy. https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2023/02/03/the-giedroyc-mieroszewski-doctrine-and-polands-response-to-russias-assault-on-ukraine/

External links

[edit]- „Jeśli nie ULB, to co? Doktryna Giedroycia w XXI w.” ("If Not ULB, Then What? The Giedroyc Doctrine in the 21st Century", 17 June 2010)

- Bartłomiej Sienkiewicz, "Pożegnanie z Giedroyciem" ("Farewell to Giedroyc", Rzeczpospolita, 28-05-2010).

- Zdzisław Najder, "'Doktryna ULB – koncepcja Giedroycia i Mieroszewskiego w XXI wieku" ("The ULB Doctrine: Giedroyc's and Mieroszewski's Concept in the 21st century"). [1].

- Marcin Wojciechowski, "Co po Giedroyciu? Giedroyc!" ("What Comes after Giedroyc? Giedroyc!"), Nowa Europa Wschodnia (New Eastern Europe), 1/2010, pp. 69–77.