Yahweh: Difference between revisions

Countercheck (talk | contribs) clean up, typo(s) fixed: from 586–539 → from 586 to 539; delinked duplicate links |

|||

| (33 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Ancient Levantine deity}} |

{{Short description|Ancient Levantine deity}} |

||

{{About|the ancient Levantine deity|the modern Judeo-Christian conception |

{{About|the ancient Levantine deity of Israel and Judah|the modern Judeo-Christian conception|God in Judaism|and|God in Christianity|8=the name "YHWH" and its vocalization|9=Tetragrammaton|10=other uses}} |

||

{{pp-move |

{{pp-move}} |

||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2022}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2022}} |

||

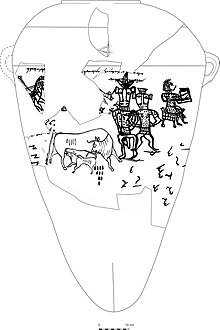

| ⚫ | [[File:Zeus Yahweh.jpg|thumb|alt=A coin showing a bearded figure seating on a winged wheel, holding a bird on his outstretched hand|The [[God on the Winged Wheel coin]], minted in [[Gaza City]], southern [[Philistia]], during the [[Eber-Nari|Persian period]] of the 4th century BCE. It possibly represents Yahweh enthroned on a [[winged wheel]],{{sfn|Edelman|1995|p=190}}{{sfn|Stavrakopoulou|2021|pp=411–412, 742}} although this identification is disputed among scholars.{{sfn|Pyschny|2021|pp=26–27}}]]{{Middle Eastern deities}} |

||

{{Middle Eastern deities}} |

|||

'''Yahweh'''{{efn|name="name"|1={{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|hw|eɪ}}, or often {{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|w|eɪ}} in English; 𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄 in [[Paleo-Hebrew alphabet|Paleo-Hebrew]]; [[Tetragrammaton#Yahweh|reconstructed]] in {{langx|he|{{Script/Hebrew|*יַהְוֶה}}|label=block script}} *''Yahwe'', {{IPA|he|jahˈwe|}}}} was an [[Religions of the ancient Near East|ancient Levantine deity]] who was venerated in [[History of ancient Israel and Judah|Israel and Judah]].{{sfn|Miller|Hayes|1986|p=110}}{{sfn|Niehr|1995|p=54-55}} Though no consensus exists regarding his origins,{{sfn|Fleming|2020|p=3}} scholars generally contend that he is associated with [[Mount Seir|Seir]], [[Edom]], [[Desert of Paran|Paran]] and [[Teman (Edom)|Teman]],{{sfn|Smith|2017|p=42}} and later with [[Canaan]]. His worship reaches back to at least the [[Early Iron Age]], and likely to the [[Late Bronze Age]], if not somewhat earlier.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=1}} While the [[Israelites]] held him as their [[national god]], their religion—known as [[Yahwism]], involving the worship of Yahweh among a broader [[Pantheon (religion)|Semitic pantheon]]—was still essentially [[polytheistic]] or, according to some accounts, [[Monolatry#In ancient Israel|monolatristic]].{{efn|{{harvnb|Sommer|2009|loc=p. 145: "It is a commonplace of modern biblical scholarship that Israelite religion prior to the Babylonian exile was basically polytheistic. [...] Many scholars argue that ancient Israelites worshipped a plethora of gods and goddesses [...]."}}}} However, during and after the [[Babylonian captivity]] in the 6th century BCE, the Israelite religion gradually evolved into [[Judaism]] and [[Samaritanism]], which are both strictly [[Monotheism|monotheistic]] and thus regard Yahweh as [[God in Abrahamic religions|God]] in the singular sense—that is, as the supreme being of the universe and without any equals. |

|||

[[File:Solebinscription.png|right|thumb|[[Soleb]] inscription, "Yhwʒ" of [[Shasu]], oldest known reference to Yahweh, [[Nubia]]<ref>{{Citation |title=Yhwʒ of Shasu-Land |date=2020-12-03 |work=Yahweh before Israel |pages=23–66 |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781108875479.003 |access-date=2024-09-14 |publisher=Cambridge University Press|doi=10.1017/9781108875479.003 |isbn=978-1-108-87547-9 }}</ref>]] |

|||

'''Yahweh'''{{efn|name="name"|1={{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|hw|eɪ}}, or often {{IPAc-en|ˈ|j|ɑː|w|eɪ}} in English; 𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄 in [[Paleo-Hebrew alphabet|Paleo-Hebrew]]; [[Tetragrammaton#Yahweh|reconstructed]] in {{lang-he|{{Script/Hebrew|*יַהְוֶה}}|label=block script}} *''Yahwe'', {{IPA|he|jahˈwe|}}}} was an ancient [[Levant]]ine deity, the [[national god]] of the [[Israelites|Israelite]] kingdoms of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Israel]] and [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]],{{sfn|Miller|Hayes|1986|p=110}} and later the god of [[Judaism]] and its other descendant [[Abrahamic religions]]. Though no consensus exists regarding the deity's origins,{{sfn|Fleming|2020|p=3}} scholars generally contend that Yahweh is associated with [[Mount Seir|Seir]], [[Edom]], [[Desert of Paran|Paran]] and [[Teman (Edom)|Teman]],{{sfn|Smith|2017|p=42}} and later with [[Canaan]]. The origins of his worship reach at least to the early [[Iron Age]], and likely to the Late [[Bronze Age]], if not somewhat earlier.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=1}} |

|||

In the oldest [[biblical |

In the oldest examples of [[biblical literature]], Yahweh possesses attributes that were typically ascribed to deities of [[Weather god|weather]] and [[List of war deities|war]], fructifying the [[Land of Israel]] and leading a [[Heavenly host#Tanakh|heavenly army]] against the nation's enemies.{{sfn|Hackett|2001|pp=158–59}} The early Israelites may have leaned towards polytheistic practices that were otherwise common across [[ancient Semitic religion]], as their worship apparently included a variety of [[Canaanite religion|Canaanite gods and goddesses]], such as [[El (deity)|El]], [[Asherah]], and [[Baal]].{{sfn|Smith|2002|page=7}} |

||

In later centuries, |

In later centuries, El and Yahweh became conflated, and El-linked epithets, such as {{Transliteration|he|[[El Shaddai|ʾĒl Šadday]]}} ({{Script/Hebrew|אֵל שַׁדַּי}}), came to be applied to Yahweh alone.{{sfn|Smith|2002|pages=8, 33–34}} Some scholars believe that El and Yahweh were always conflated.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|p=222}}{{sfn|Cross|1973|pp=96–97}}{{sfn|Cornell|2021|p=18}} Characteristics of other deities, such as Asherah and Baal, were also selectively "absorbed" in conceptions of Yahweh.{{sfn|Smith|2002|pages=8, 135}}{{sfn|Smith|2017|p=38}}{{sfn|Cornell|2021|p=20}} |

||

Over time the existence of other |

Over time, the existence of other deities was denied outright, and Yahweh was proclaimed the [[creator deity]] and the sole divinity to be worthy of worship. During the [[Second Temple period]], openly speaking the name of Yahweh in public became regarded as a religious taboo,{{sfn|Leech|2002|pp=59–60}} and [[Jews]] instead began to substitute [[Names of God in Judaism#Adonai|other Hebrew words]], primarily {{Transliteration|he|ăḏōnāy}} ({{Script/Hebrew|אֲדֹנָי}}, {{Literal translation|My [[Pluralis majestatis|Lords]]}}). By the time of the [[Jewish–Roman wars]]—namely following the [[Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE)|Roman siege of Jerusalem]] and the concomitant destruction of the [[Second Temple]] in 70 CE—the [[YHWH|original pronunciation of Yahweh's name]] was forgotten entirely.{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} |

||

Yahweh is |

Additionally, Yahweh is invoked in the [[Aramaic]]-language [[Papyrus Amherst 63]] from [[ancient Egypt]], and also in Jewish or Jewish-influenced [[Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri|Greco-Egyptian magical texts]] from the 1st to 5th centuries CE.{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} |

||

==Name== |

==Name== |

||

[[File:Tetragrammaton Sefardi.jpg|thumb|The [[Tetragrammaton]], inscribed on the page of a [[Sephardi Hebrew|Sephardic]] [[Torah scroll|manuscript]] of the [[Hebrew Bible]], 1385]] |

|||

The god's name was written in [[Paleo-Hebrew alphabet|paleo-Hebrew]] as {{lang|he-Phnx|𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄}} ({{Script/Hebrew|יהוה}} in [[Hebrew alphabet|block script]]), transliterated as [[YHWH]]; modern scholarship has reached consensus to transcribe this as "Yahweh".<ref>{{harvnb|Alter|2018|p=<!--unpaginated-->}}: "The strong consensus of biblical scholarship is that the original pronunciation of the name YHWH ... was Yahweh."</ref> The shortened forms ''Yeho''-, ''Yahu''- and ''Yo''- appear in [[Theophory in the Bible#Yah theophory|personal names]] and in phrases such as "[[Hallelujah|Hallelu''jah'']]!"{{sfn|Preuss|2008|p=823}} The sacrality of the name, as well as the [[Ten Commandments|Commandment]] against "[[Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain|taking the name 'in vain']]{{hair space}}", led to increasingly strict prohibitions on speaking or writing the term. Rabbinic sources suggest that, by the [[Second Temple Judaism|Second Temple period]], the name of God was pronounced only once a year, by the |

The god's name was written in [[Paleo-Hebrew alphabet|paleo-Hebrew]] as {{lang|he-Phnx|𐤉𐤄𐤅𐤄}} ({{Script/Hebrew|יהוה}} in [[Hebrew alphabet|block script]]), transliterated as [[YHWH]]; modern scholarship has reached consensus to transcribe this as "Yahweh".<ref>{{harvnb|Alter|2018|p=<!--unpaginated-->}}: "The strong consensus of biblical scholarship is that the original pronunciation of the name YHWH ... was Yahweh."</ref> The shortened forms ''Yeho''-, ''Yahu''-, ''[[Jah|Yah]]''- and ''Yo''- appear in [[Theophory in the Bible#Yah theophory|personal names]] and in phrases such as "[[Hallelujah|Hallelu''jah'']]!"{{sfn|Preuss|2008|p=823}} The sacrality of the name, as well as the [[Ten Commandments|Commandment]] against "[[Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain|taking the name 'in vain']]{{hair space}}", led to increasingly strict prohibitions on speaking or writing the term. Rabbinic sources suggest that, by the [[Second Temple Judaism|Second Temple period]], the name of God was officially pronounced only once a year, by the [[High Priest of Israel|High Priest]], on the [[Yom Kippur|Day of Atonement]].<ref>{{harvnb|Elior|2006|p=779}}: "... the pronunciation of the Ineffable Name was one of the climaxes of the Sacred Service: it was entrusted exclusively to the High Priest once a year on the Day of Atonement in the Holy of Holies."</ref> After the [[Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE)|destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE]], the original pronunciation of the name was forgotten entirely.{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:כתובת אריהו מפורשת.jpg|right|thumb|Uriyahu inscription, [[Khirbet el-Qom]], 8th c. BCE, "Blessed is/be Uriyahu by Yahweh"]] |

[[File:כתובת אריהו מפורשת.jpg|right|thumb|Uriyahu inscription, [[Khirbet el-Qom]], 8th c. BCE, "Blessed is/be Uriyahu by Yahweh"]] |

||

===Periods=== |

===Periods=== |

||

[[Philip King (historian)|Philip King]] and [[Lawrence Stager]] place the history of Yahweh into the following periods: |

[[Philip King (historian)|Philip King]] and [[Lawrence Stager]] place the history of Yahweh into the following periods: |

||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

* Neo-Babylonian: 586–539 BCE |

* Neo-Babylonian: 586–539 BCE |

||

* Persian: 539–332 BCE{{sfn|King|Stager|2001|p=xxiii}} |

* Persian: 539–332 BCE{{sfn|King|Stager|2001|p=xxiii}} |

||

Other academic terms often used include First Temple period, from the construction of the [[Temple in Jerusalem|Temple]] in 957 BCE to its destruction in 586 BCE, exilic for the period of the Exile from |

Other academic terms often used include First Temple period, from the construction of the [[Temple in Jerusalem|Temple]] in 957 BCE to its destruction in 586 BCE, exilic for the period of the Exile from 586 to 539 BCE (identical with Neo-Babylonian above), post-Exilic for later periods and [[Second Temple period]] from the reconstruction of the Temple in 515 BCE until its destruction in 70 CE. |

||

===Late Bronze Age origins (1550–1200 BCE)=== |

===Late Bronze Age origins (1550–1200 BCE)=== |

||

| ⚫ | There is almost no agreement on Yahweh's origins.{{sfn|Fleming|2020|p=3}} His name is not attested other than among the Israelites, and there is no consensus on its etymology, with ''ehyeh ašer ehyeh'' ("[[I Am that I Am]]"), the explanation presented in [[Book of Exodus|Exodus]] 3:14,<ref>{{bibleverse||Exodus|3:14|HE}}</ref> appearing to be a late theological [[Gloss (annotation)|gloss]] invented at a time when the original meaning had been forgotten,{{sfn|Parke-Taylor|1975|p=51}} although some scholars dispute this.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|page=214}}{{sfn|Miller II|2021|p=18}} Lewis connects the name to the [[Amorite language|Amorite]] element ''yahwi-'' (''ia-wi''), found in personal names in [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] texts,{{sfn|Kitz|2019|pp=42, 57}} meaning "brings to life/causes to exist" (e.g. ''yahwi-dagan'' = "[[Dagon]] causes to exist"), commonly denoted as the semantic equivalent of the [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] ''ibašši-''DN;{{sfn|Lewis|2020|pp=211, 215}} though [[Frank Moore Cross]] emphasized that the Amorite verbal form is of interest only in attempting to reconstruct the verbal root of the name "Yahweh", and that attempts to take ''yahwi-'' as a divine epithet should be "vigorously" argued against.{{sfn|Cross|1973|pp=61-63}}<ref>{{harvnb|Fleming|2020|p=176}}: "There has been one key objection, by Michael Streck, who reevaluated Amorite personal names as a whole in 2000 and as part of this work published the separate conclusion (1999) that all the ''Ya-wi-'' and ''Ya-aḫ-wi-'' elements in these names must be understood to reflect the same root ''ḥwy'', "to live"....If Streck is correct that these are all forms of the verb "to live", then the Amorite personal names must be set aside as useful to any interpretation of the name [Yahweh]." But see {{harvnb|Fleming|2020b|p=425}}: "While the identification of the verbal root in the Amorite names with and without the -''ḫ''- remains impossible to prove with certainty, the parallels with contemporary Old Babylonian Ibašši-DN and the later second-millennium parallels from the verb ''kwn'' show the viability of a West Semitic root ''hwy'', "to be, be evident", for at least some portion of these Amorite names."</ref> In addition, J. Philip Hyatt believes it is more likely that ''yahwi-'' refers to a god creating and sustaining the life of a newborn child rather than the universe. This conception of God was more popular among ancient Near Easterners but eventually, the Israelites removed the association of ''yahwi-'' to any human ancestor and combined it with other elements (e.g. ''Yahweh ṣəḇāʾōṯ'').<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hyatt |first=J. Philip |date=1967 |title=Was Yahweh Originally a Creator Deity? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3262791 |journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |volume=86 |issue=4 |pages=369–377 |doi=10.2307/3262791 |jstor=3262791 }}</ref>{{Update inline|date=April 2024|reason=The source is literally almost 60 years old.}} Hillel Ben-Sasson states there is insufficient evidence for Amorites using ''yahwi-'' for gods, but he argues that it mirrors other theophoric names and that ''yahwi-'', or more accurately ''yawi'', derives from the root ''hwy'' in ''pa'al,'' which means "he will be".{{sfn|Ben-Sasson|2019|pp=55–56}} |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Zeus Yahweh.jpg|thumb|alt=A coin showing a bearded figure seating on a winged wheel, holding a bird on his outstretched hand|The [[God on the Winged Wheel coin]], |

||

| ⚫ | There is almost no agreement on Yahweh's origins.{{sfn|Fleming|2020|p=3}} His name is not attested other than among the Israelites, and there is no consensus on its etymology, with ''ehyeh ašer ehyeh'' ("[[I Am that I Am]]"), the explanation presented in [[Book of Exodus|Exodus]] 3:14,<ref>{{bibleverse||Exodus|3:14|HE}}</ref> appearing to be a late theological [[Gloss (annotation)|gloss]] invented at a time when the original meaning had been forgotten,{{sfn|Parke-Taylor|1975|p=51}} although some scholars dispute this.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|page=214}}{{sfn|Miller II|2021|p=18}} Lewis connects the name to the [[Amorite language|Amorite]] element ''yahwi-'' (''ia-wi''), found in personal names in [[Mari, Syria|Mari]] texts,{{sfn|Kitz|2019|pp=42, 57}} meaning "brings to life/causes to exist" (e.g. ''yahwi-dagan'' = "[[Dagon]] causes to exist"), commonly denoted as the semantic equivalent of the [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] ''ibašši-''DN;{{sfn|Lewis|2020|pp=211, 215}} though [[Frank Moore Cross]] emphasized that the Amorite verbal form is of interest only in attempting to reconstruct the verbal root of the name "Yahweh", and that attempts to take ''yahwi-'' as a divine epithet should be "vigorously" argued against.{{sfn|Cross|1973|pp=61-63}}<ref>{{harvnb|Fleming|2020|p=176}}: "There has been one key objection, by Michael Streck, who reevaluated Amorite personal names as a whole in 2000 and as part of this work published the separate conclusion (1999) that all the ''Ya-wi-'' and ''Ya-aḫ-wi-'' elements in these names must be understood to reflect the same root ''ḥwy'', "to live"....If Streck is correct that these are all forms of the verb "to live", then the Amorite personal names must be set aside as useful to any interpretation of the name [Yahweh]." But see {{harvnb|Fleming|2020b|p=425}}: "While the |

||

One scholarly theory is that "Yahweh" originated in a shortened form of ''ˀel ḏū yahwī ṣabaˀôt'', "El who creates the hosts",{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=2}} which Cross considered to be one of the cultic names of El.{{sfn|Cross|1973|p=71}} However, this phrase is nowhere attested either inside or outside the Bible, and the two gods are in any case quite dissimilar, with El being elderly and paternal and lacking Yahweh's association with the storm and battles.{{sfn|Day|2002|pp=13–14}} Even if the above issues are resolved, Yahweh is generally agreed to have a non-causative etymology because otherwise, YHWH would be translated as YHYH.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|p=222}} It also raises the question of why the Israelites would want to shorten the epithet. One possible reason includes the co-existence of religious modernism and conservatism being the norm in all religions.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|p=222}} |

One scholarly theory is that "Yahweh" originated in a shortened form of ''ˀel ḏū yahwī ṣabaˀôt'', "El who creates the hosts",{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=2}} which Cross considered to be one of the cultic names of El.{{sfn|Cross|1973|p=71}} However, this phrase is nowhere attested either inside or outside the Bible, and the two gods are in any case quite dissimilar, with El being elderly and paternal and lacking Yahweh's association with the storm and battles.{{sfn|Day|2002|pp=13–14}} Even if the above issues are resolved, Yahweh is generally agreed to have a non-causative etymology because otherwise, YHWH would be translated as YHYH.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|p=222}} It also raises the question of why the Israelites would want to shorten the epithet. One possible reason includes the co-existence of religious modernism and conservatism being the norm in all religions.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|p=222}} |

||

The oldest plausible occurrence of Yahweh's name is in the [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] [[demonym]] ''[[wikt:tꜣ-šꜣsw-yhwꜣ|tꜣ šꜣsw Yhwꜣ]]'', "''YHWA'' (in) the Land of the [[Shasu]]" ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]]: {{Script/Egyp|𓇌𓉔𓍯𓄿}} ''Yhwꜣ'') in an inscription from the time of [[Amenhotep III]] (1390–1352 BCE),{{sfn|Shalomi Hen|2021}}{{sfn|Anderson|2015|p=100}} the [[Shasu]] being nomads from [[Midian]] and |

The oldest plausible occurrence of Yahweh's name is in the [[Egyptian language|Egyptian]] [[demonym]] ''[[wikt:tꜣ-šꜣsw-yhwꜣ|tꜣ šꜣsw Yhwꜣ]]'', "''YHWA'' (in) the Land of the [[Shasu]]" ([[Egyptian language|Egyptian]]: {{Script/Egyp|𓇌𓉔𓍯𓄿}} ''Yhwꜣ'') in an inscription from the time of [[Amenhotep III]] (1390–1352 BCE),{{sfn|Shalomi Hen|2021}}{{sfn|Anderson|2015|p=100}} the [[Shasu]] being nomads from [[Midian]] and Edom in northern Arabia.{{sfn|Grabbe|2007|p=151}} Although it is still uncertain whether a relationship exists between the toponym ''yhwꜣ'' and theonym ''YHWH'',<ref>{{harvnb|Shalomi Hen|2021}}: "Unfortunately, albeit the interesting analogies, the learned discussions, and the broad perspective, the evidence is too scanty to allow any conclusions concerning the exact meaning of the term YHWA/YHA/YH as it appears in Ancient Egyptian records."</ref> the dominant view is that Yahweh was from the southern region associated with [[Mount Seir|Seir]], Edom, [[Desert of Paran|Paran]] and [[Teman (Edom)|Teman]].{{sfn|Smith|2017|p=42}} There is considerable although not universal support for this view,{{sfn|Grabbe|2007|p=153}} but it raises the question of how Yahweh made his way to the north.{{sfn|Van der Toorn|1999|p=912}} An answer many scholars consider plausible is the [[Kenite hypothesis]], which holds that traders brought Yahweh to Israel along the [[Caravan (travellers)|caravan]] routes between [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] and [[Canaan]].{{sfn|Van der Toorn|1999|pp=912–13}} This ties together various points of data, such as the absence of Yahweh from Canaan, his links with Edom and [[Midian]] in the biblical stories, and the [[Kenite]] or Midianite ties of [[Moses]],{{sfn|Van der Toorn|1999|page=912}} but its major weaknesses are that the majority of Israelites were firmly rooted in [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]], while the historical role of Moses is problematic.{{sfn|Van der Toorn|1995|pp=247–248}} It follows that if the Kenite hypothesis is to be maintained, then it must be assumed that the Israelites encountered Yahweh (and the Midianites/Kenites) inside Israel and through their association with the earliest political leaders of Israel.{{sfn|Van der Toorn|1995|p=248}} Christian Frevel argues that inscriptions allegedly suggesting Yahweh's southern origins (e.g. "YHWH of Teman") may simply denote his presence there at later times, and that Teman can refer to any southern territory, including Judah.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

Alternatively, some scholars argue that YHWH worship was rooted in the indigenous culture of the [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Kingdom of Israel]] and was promoted in the [[Kingdom of Judah]] by the [[Omrides]].<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |last=Frevel |first=Christian |date=2021 |title=When and from Where did YHWH Emerge? Some Reflections on Early Yahwism in Israel and Judah |journal=Entangled Religions |volume=12 |issue=2 |doi=10.46586/er.12.2021.8776 |issn=2363-6696 |doi-access=free|hdl=2263/84039 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":3">{{cite journal |title=God's Best 'Frenemy': A New Perspective on YHWH and Baal in Ancient Israel and Judah |journal=Semitica |url=https://www.academia.edu/45062733 |last=Stahl |first=Michael J. |volume=63 |pages=45–94 |doi=10.2143/SE.63.0.3289896 |year=2021 |issn=2466-6815}}</ref> Frevel suggests that [[Hazael]]'s conquests in the Kingdom of Israel forced the two kingdoms to cooperate, which spread YHWH worship among Judean commoners. Previously, YHWH was viewed as the patron god of the Judean ''state''.<ref name=":0" /> |

Alternatively, some scholars argue that YHWH worship was rooted in the indigenous culture of the [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Kingdom of Israel]] and was promoted in the [[Kingdom of Judah]] by the [[Omrides]].<ref name=":0">{{cite journal |last=Frevel |first=Christian |date=2021 |title=When and from Where did YHWH Emerge? Some Reflections on Early Yahwism in Israel and Judah |journal=Entangled Religions |volume=12 |issue=2 |doi=10.46586/er.12.2021.8776 |issn=2363-6696 |doi-access=free|hdl=2263/84039 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":3">{{cite journal |title=God's Best 'Frenemy': A New Perspective on YHWH and Baal in Ancient Israel and Judah |journal=Semitica |url=https://www.academia.edu/45062733 |last=Stahl |first=Michael J. |volume=63 |pages=45–94 |doi=10.2143/SE.63.0.3289896 |year=2021 |issn=2466-6815}}</ref> Frevel suggests that [[Hazael]]'s conquests in the Kingdom of Israel forced the two kingdoms to cooperate, which spread YHWH worship among Judean commoners. Previously, YHWH was viewed as the patron god of the Judean ''state''.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

| Line 52: | Line 53: | ||

... |

... |

||

From the sky the stars fought. |

From the sky the stars fought. |

||

From their courses, they fought against [[Sisera]]. |

From their courses, they fought against [[Sisera]]. |

||

([[Book of Judges]] 5:4–5, 20, ''WEB'' [[World English Bible]], the [[Song of Deborah]].)}} |

([[Book of Judges]] 5:4–5, 20, ''WEB'' [[World English Bible]], the [[Song of Deborah]].)}} |

||

| Line 86: | Line 87: | ||

Nonetheless, some scholars argue that El Elyon ("the Most High") and Yahweh are [[theonyms]] for the same deity in the text, based on contextual analysis.{{sfn|Hess|2007|pp=103–104}}{{sfn|Smith|2008|p=203}} |

Nonetheless, some scholars argue that El Elyon ("the Most High") and Yahweh are [[theonyms]] for the same deity in the text, based on contextual analysis.{{sfn|Hess|2007|pp=103–104}}{{sfn|Smith|2008|p=203}} |

||

The late [[Iron Age]] saw the emergence of [[nation state]]s associated with specific [[national god]]s:{{sfn|Schniedewind|2013|p=93}} [[Chemosh]] was the god of the Moabites, [[Milcom]] the god of the Ammonites, Qōs the god of the Edomites, and Yahweh the god of the Israelites.{{sfn|Hackett|2001|p=156}}{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} In each kingdom the king was also the head of the national religion and thus the [[viceroy]] on Earth of the national god.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=90}} Yahweh filled the role of national god in the [[kingdom of Israel (Samaria)]], which emerged in the 10th century BCE; and also in [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]], which may have emerged a century later{{sfn|Geller|2012|p=unpaginated}} (no "God of Judah" is mentioned anywhere in the Bible).{{sfn|Hackett|2001|p=156}}{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} |

The late [[Iron Age]] saw the emergence of [[nation state]]s associated with specific [[national god]]s:{{sfn|Schniedewind|2013|p=93}} [[Chemosh]] was the god of the Moabites, [[Milcom]] the god of the Ammonites, Qōs the god of the Edomites, and Yahweh the god of the Israelites.{{sfn|Hackett|2001|p=156}}{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} In each kingdom the king was also the head of the national religion and thus the [[viceroy]] on Earth of the national god.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=90}} Yahweh filled the role of national god in the [[kingdom of Israel (Samaria)]], which emerged in the 10th century BCE; and also in [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]], which may have emerged a century later{{sfn|Geller|2012|p=unpaginated}} (no "God of Judah" is mentioned anywhere in the Bible).{{sfn|Hackett|2001|p=156}}{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} |

||

During the reign of [[Ahab]], and particularly following his marriage to [[Jezebel]], Baal may have briefly replaced Yahweh as the national god of Israel (but not Judah).{{sfn|Smith|2002|pp=71–72}}{{sfn|Campbell|2001|pp=221–222}} |

During the reign of [[Ahab]], and particularly following his marriage to [[Jezebel]], Baal may have briefly replaced Yahweh as the national god of Israel (but not Judah).{{sfn|Smith|2002|pp=71–72}}{{sfn|Campbell|2001|pp=221–222}} |

||

| Line 92: | Line 93: | ||

In the [[9th century BCE]], there are indications of rejection of Baal worship associated with the prophets [[Elijah]] and [[Elisha]]. The Yahweh-religion thus began to separate itself from its Canaanite heritage; this process continued over the period from 800 to 500 BCE with legal and prophetic condemnations of the [[asherim]], [[sun worship]] and worship on the [[high place]]s, along with practices pertaining to the dead and other aspects of the old religion.{{sfn|Smith|2002|page=9}} Features of Baal, El, and Asherah were absorbed into Yahweh, and epithets such as [[El Shaddai]] came to be applied to Yahweh alone.{{sfn|Smith|2002|pp=8, 33–34, 135}} |

In the [[9th century BCE]], there are indications of rejection of Baal worship associated with the prophets [[Elijah]] and [[Elisha]]. The Yahweh-religion thus began to separate itself from its Canaanite heritage; this process continued over the period from 800 to 500 BCE with legal and prophetic condemnations of the [[asherim]], [[sun worship]] and worship on the [[high place]]s, along with practices pertaining to the dead and other aspects of the old religion.{{sfn|Smith|2002|page=9}} Features of Baal, El, and Asherah were absorbed into Yahweh, and epithets such as [[El Shaddai]] came to be applied to Yahweh alone.{{sfn|Smith|2002|pp=8, 33–34, 135}} |

||

In this atmosphere a struggle emerged between those who believed that Yahweh alone should be worshipped, and those who worshipped him within a larger group of gods;{{sfn|Sperling|2017|p=254}} the Yahweh-alone party, the party of the [[prophet]]s and [[Deuteronomist]]s, ultimately triumphed, and their victory lies behind the biblical narrative of an Israel vacillating between periods of "following other gods" and periods of [[fidelity]] to Yahweh.{{sfn|Sperling|2017|p=254}} |

In this atmosphere a struggle emerged between those who believed that Yahweh alone should be worshipped, and those who worshipped him within a larger group of gods;{{sfn|Sperling|2017|p=254}} the Yahweh-alone party, the party of the [[prophet]]s and [[Deuteronomist]]s, ultimately triumphed, and their victory lies behind the biblical narrative of an Israel vacillating between periods of "following other gods" and periods of [[fidelity]] to Yahweh.{{sfn|Sperling|2017|p=254}} |

||

Some scholars date the start of widespread monotheism to the [[8th century BC |

Some scholars date the start of widespread monotheism to the [[8th century BC]]E, and view it as a response to [[Neo-Assyrian Empire|Neo-Assyrian]] aggression.{{sfn|Smith|2016|p=287}}{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=61}} In an inscription discovered in [[Ein Gedi]] and dated around 700 BCE, Yahweh appears described as the lord of "the nations", while in other contemporary texts discovered in [[Khirbet Beit Lei]] (near Lachish) he is mentioned as the ruler of Jerusalem and probably also of Judah.{{sfn|Hess|2020|p=247–248}} |

||

===Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods (586–332 BCE)=== |

===Neo-Babylonian and Persian Periods (586–332 BCE)=== |

||

| Line 100: | Line 101: | ||

[[File:Jerus-n4i.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|alt=A model building, with a large cubic structure to the rear and an open courtyard in front, surrounded by crenelated and turreted walls|The [[Holyland Model of Jerusalem]]'s representation of the [[Second Temple]], as [[Herod's temple|rebuilt]] by [[Herod the great|Herod]] c. 20–10 BCE (modern model, 1:50 scale)]] |

[[File:Jerus-n4i.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|alt=A model building, with a large cubic structure to the rear and an open courtyard in front, surrounded by crenelated and turreted walls|The [[Holyland Model of Jerusalem]]'s representation of the [[Second Temple]], as [[Herod's temple|rebuilt]] by [[Herod the great|Herod]] c. 20–10 BCE (modern model, 1:50 scale)]] |

||

In 587/6 BCE [[Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC)|Jerusalem fell]] to the [[Neo-Babylonian]]s, [[Solomon's Temple]] was destroyed, and the leadership of the community were deported.{{sfn|Grabbe|2010|p=2}} The next 50 years, the [[Babylonian exile]], were of pivotal importance to the history of Israelite religion. As the traditional [[sacrifice]]s to Yahweh (see below) could not be performed outside Israel, other practices including [[Biblical Sabbath|sabbath]] observance and [[Brit milah|circumcision]] gained new significance.{{sfn|Cogan|2001|p=271}} In the writing of [[second Isaiah]], Yahweh was no longer seen as exclusive to Israel, but as extending his promise to all who would keep the sabbath and observe his covenant.{{sfn|Cogan|2001|p=274}} In 539 BCE [[Fall of Babylon|Babylon in turn fell]] to the Persian conqueror [[Cyrus the Great]], the exiles were given permission to return (although only a minority did so), and by about 500 BCE the |

In 587/6 BCE [[Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC)|Jerusalem fell]] to the [[Neo-Babylonian]]s, [[Solomon's Temple]] was destroyed, and the leadership of the community were deported.{{sfn|Grabbe|2010|p=2}} The next 50 years, the [[Babylonian exile]], were of pivotal importance to the history of Israelite religion. As the traditional [[sacrifice]]s to Yahweh (see below) could not be performed outside Israel, other practices including [[Biblical Sabbath|sabbath]] observance and [[Brit milah|circumcision]] gained new significance.{{sfn|Cogan|2001|p=271}} In the writing of [[second Isaiah]], Yahweh was no longer seen as exclusive to Israel, but as extending his promise to all who would keep the sabbath and observe his covenant.{{sfn|Cogan|2001|p=274}} In 539 BCE [[Fall of Babylon|Babylon in turn fell]] to the Persian conqueror [[Cyrus the Great]], the exiles were given permission to return (although only a minority did so), and by about 500 BCE the Second Temple was built.{{sfn|Grabbe|2010|pp=2–3}} |

||

Towards the end of the Second Temple period, speaking the name of Yahweh in public became regarded as [[taboo]].{{sfn|Leech|2002|pp=59–60}} When reading from the scriptures, Jews began to substitute the divine name with the word ''[[adonai]]'' (אֲדֹנָי), meaning "[[Lord#Religion|my Lord]]".{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} The [[High Priest of Israel]] was permitted to speak the name once in the Temple during the [[Yom Kippur|Day of Atonement]], but at no other time and in no other place.{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} During the [[Hellenistic period]], the scriptures were translated into Greek by the Jews of the [[History of the Jews in Egypt|Egyptian diaspora]].{{sfn|Coogan|Brettler|Newsom|2007|p=xxvi}} Greek translations of the Hebrew scriptures render both the |

Towards the end of the Second Temple period, speaking the name of Yahweh in public became regarded as [[taboo]].{{sfn|Leech|2002|pp=59–60}} When reading from the scriptures, Jews began to substitute the divine name with the word ''[[adonai]]'' (אֲדֹנָי), meaning "[[Lord#Religion|my Lord]]".{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} The [[High Priest of Israel]] was permitted to speak the name once in the Temple during the [[Yom Kippur|Day of Atonement]], but at no other time and in no other place.{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} During the [[Hellenistic period]], the scriptures were translated into Greek by the Jews of the [[History of the Jews in Egypt|Egyptian diaspora]].{{sfn|Coogan|Brettler|Newsom|2007|p=xxvi}} Greek translations of the Hebrew scriptures render both the tetragrammaton and ''adonai'' as ''[[kyrios]]'' (κύριος), meaning "Lord".{{sfn|Leech|2002|p=60}} |

||

The period of Persian rule saw the development of expectation in a future human king who would rule [[Ritual purification|purified]] Israel as Yahweh's representative at the [[Jewish eschatology|end of time]]—a [[messiah]]. The first to mention this were [[Haggai]] and [[Zechariah (Hebrew prophet)|Zechariah]], both prophets of the early Persian period. They saw the messiah in [[Zerubbabel]], a descendant of the [[Davidic line|House of David]] who seemed, briefly, to be about to re-establish the ancient royal line, or in Zerubbabel and the first High Priest, [[Joshua the High Priest|Joshua]] (Zechariah writes of two messiahs, one royal and the other priestly). These early hopes were dashed (Zerubabbel disappeared from the historical record, although the High Priests continued to be descended from Joshua), and thereafter there are merely general references to a Messiah of [[David]] (i.e. a descendant).{{sfn|Wanke|1984|pp=182–183}}{{sfn|Albertz|2003|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Xx9YzJq2B9wC&pg=PA130 130]}} From these ideas, [[Second Temple Judaism]] would later emerge, whence [[Christianity]], [[Rabbinic Judaism]], and [[Islam]]. |

The period of Persian rule saw the development of expectation in a future human king who would rule [[Ritual purification|purified]] Israel as Yahweh's representative at the [[Jewish eschatology|end of time]]—a [[messiah]]. The first to mention this were [[Haggai]] and [[Zechariah (Hebrew prophet)|Zechariah]], both prophets of the early Persian period. They saw the messiah in [[Zerubbabel]], a descendant of the [[Davidic line|House of David]] who seemed, briefly, to be about to re-establish the ancient royal line, or in Zerubbabel and the first High Priest, [[Joshua the High Priest|Joshua]] (Zechariah writes of two messiahs, one royal and the other priestly). These early hopes were dashed (Zerubabbel disappeared from the historical record, although the High Priests continued to be descended from Joshua), and thereafter there are merely general references to a Messiah of [[David]] (i.e. a descendant).{{sfn|Wanke|1984|pp=182–183}}{{sfn|Albertz|2003|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Xx9YzJq2B9wC&pg=PA130 130]}} From these ideas, [[Second Temple Judaism]] would later emerge, whence [[Christianity]], [[Rabbinic Judaism]], and [[Islam]]. |

||

| Line 109: | Line 110: | ||

Although the specific process by which the Israelites adopted [[monotheism]] is unknown, the transition was a gradual one and was not totally accomplished during the First Temple period.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last1=Taliaferro |first1=Charles |title=The Routledge Companion to Theism |last2=Harrison |first2=Victoria S. |last3=Goetz |first3=Stewart |publisher=Routledge |year=2012}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=April 2024}} |

Although the specific process by which the Israelites adopted [[monotheism]] is unknown, the transition was a gradual one and was not totally accomplished during the First Temple period.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last1=Taliaferro |first1=Charles |title=The Routledge Companion to Theism |last2=Harrison |first2=Victoria S. |last3=Goetz |first3=Stewart |publisher=Routledge |year=2012}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=April 2024}} |

||

It is unclear when the worship of Yahweh alone began. The earliest known portrayals of Yahweh as the principal deity to whom "one owed the powers of blessing the land" appear in the teachings of the prophet [[Elijah]] in the 9th century BCE. This form of worship was likely well established by the time of the prophet [[Hosea]] in the 8th century BCE, in reference to disputes between Yahweh and Baal.{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=61}} The early supporters of this faction are widely regarded as being [[monolatrism|monolatrists]] rather than true [[monotheists]];{{ |

It is unclear when the worship of Yahweh alone began. The earliest known portrayals of Yahweh as the principal deity to whom "one owed the powers of blessing the land" appear in the teachings of the prophet [[Elijah]] in the 9th century BCE. This form of worship was likely well established by the time of the prophet [[Hosea]] in the 8th century BCE, in reference to disputes between Yahweh and Baal.{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=61}} The early supporters of this faction are widely regarded as being [[monolatrism|monolatrists]] rather than true [[monotheists]];{{sfn|Eakin|1971|pages=70, 263}}{{Update inline|date=April 2024|reason=The source is literally 50 years old.}} they did not believe Yahweh was the only god in existence, but instead believed that he was the only god which the people of Israel should worship.{{sfn|McKenzie|1990|page=1287}} |

||

Finally, in the national crisis of the [[Babylonian captivity|Babylonian exile]], the followers of Yahweh went a step further and outright denied that the other deities aside from Yahweh even existed, thus marking the transition from monolatrism to true monotheism.{{sfn|Betz|2000|p=917}} The notion that Yahweh is to be worshipped as the [[creator god|creator-god]] of all the earth is first elaborated by the [[Deutero-Isaiah|Second Isaiah]], a [[6th century BC|6th-century BCE]] exilic work whose case for the theological doctrine rests on Yahweh's power over other gods,{{sfn|Rosenberg|1966|p=297}}{{Update inline|date=August 2023|reason=The source is literally almost 60 years old.}} and his incomparability and singleness relative to the gods of the Babylonian religion.{{sfn|Albani|2020|p=226}}{{Synthesis inline|date=April 2024}} |

Finally, in the national crisis of the [[Babylonian captivity|Babylonian exile]], the followers of Yahweh went a step further and outright denied that the other deities aside from Yahweh even existed, thus marking the transition from monolatrism to true monotheism.{{sfn|Betz|2000|p=917}} The notion that Yahweh is to be worshipped as the [[creator god|creator-god]] of all the earth is first elaborated by the [[Deutero-Isaiah|Second Isaiah]], a [[6th century BC|6th-century BCE]] exilic work whose case for the theological doctrine rests on Yahweh's power over other gods,{{sfn|Rosenberg|1966|p=297}}{{Update inline|date=August 2023|reason=The source is literally almost 60 years old.}} and his incomparability and singleness relative to the gods of the Babylonian religion.{{sfn|Albani|2020|p=226}}{{Synthesis inline|date=April 2024}} |

||

| Line 119: | Line 120: | ||

===Festivals and sacrifice=== |

===Festivals and sacrifice=== |

||

{{also|Feast of Wine}} |

{{see also|Feast of Wine}} |

||

The centre of Yahweh's worship lay in three great annual festivals coinciding with major events in rural life: [[Passover]] with the birthing of [[Sheep|lambs]], [[Shavuot]] with the [[cereal]] [[harvest]], and [[Sukkot]] with the [[fruit]] harvest.{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=89}} These probably pre-dated the arrival of the Yahweh religion,{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=89}} but they became linked to events in the [[national myth]]os of Israel: Passover with [[the exodus]] from Egypt, Shavuot with the law-giving at [[Mount Sinai (Bible)|Mount Sinai]], and Sukkot with the [[wilderness]] wanderings.{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} The festivals thus celebrated Yahweh's [[salvation]] of Israel and Israel's status as his holy people, although the earlier agricultural meaning was not entirely lost.{{sfn|Gorman|2000|p=458}} His worship presumably involved sacrifice, but many scholars have concluded that the rituals detailed in [[Leviticus]] 1–16, with their stress on purity and [[Atonement in Judaism|atonement]], were introduced only after the [[Babylonian exile]], and that in reality any head of a family was able to offer sacrifice as occasion demanded.{{sfn|Davies|Rogerson|2005|pp=151–152}} A number of scholars have also drawn the conclusion that [[infant sacrifice]], whether to the underworld deity [[Molech]] or to Yahweh himself, was a part of Israelite/Judahite religion until the reforms of [[King Josiah]] in the late 7th century BCE.{{sfn|Gnuse|1997|p=118}} Sacrifice was presumably complemented by the singing or recital of [[Book of Psalms|psalms]], but again the details are scant.{{sfn|Davies|Rogerson|2005|pp=158–165}} [[Jewish prayer|Prayer]] played little role in official worship.{{sfn|Cohen|1999|p=302}} |

The centre of Yahweh's worship lay in three great annual festivals coinciding with major events in rural life: [[Passover]] with the birthing of [[Sheep|lambs]], [[Shavuot]] with the [[cereal]] [[harvest]], and [[Sukkot]] with the [[fruit]] harvest.{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=89}} These probably pre-dated the arrival of the Yahweh religion,{{sfn|Albertz|1994|p=89}} but they became linked to events in the [[national myth]]os of Israel: Passover with [[the exodus]] from Egypt, Shavuot with the law-giving at [[Mount Sinai (Bible)|Mount Sinai]], and Sukkot with the [[wilderness]] wanderings.{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} The festivals thus celebrated Yahweh's [[salvation]] of Israel and Israel's status as his holy people, although the earlier agricultural meaning was not entirely lost.{{sfn|Gorman|2000|p=458}} His worship presumably involved sacrifice, but many scholars have concluded that the rituals detailed in [[Leviticus]] 1–16, with their stress on purity and [[Atonement in Judaism|atonement]], were introduced only after the [[Babylonian exile]], and that in reality any head of a family was able to offer sacrifice as occasion demanded.{{sfn|Davies|Rogerson|2005|pp=151–152}} A number of scholars have also drawn the conclusion that [[infant sacrifice]], whether to the underworld deity [[Molech]] or to Yahweh himself, was a part of Israelite/Judahite religion until the reforms of [[King Josiah]] in the late 7th century BCE.{{sfn|Gnuse|1997|p=118}} Sacrifice was presumably complemented by the singing or recital of [[Book of Psalms|psalms]], but again the details are scant.{{sfn|Davies|Rogerson|2005|pp=158–165}} [[Jewish prayer|Prayer]] played little role in official worship.{{sfn|Cohen|1999|p=302}} |

||

===Temples=== |

===Temples=== |

||

[[File:Tissot Solomon Dedicates the Temple at Jerusalem.jpg|thumb|alt=In the foreground, a bearded man dressed in an impressive white robe and head-dress raises his hand to heaven. Behind him, a large crowd bows in prayer.|[[Solomon]] dedicates the Temple at Jerusalem (painting by [[James Tissot]] or follower, c. 1896–1902).]] |

[[File:Tissot Solomon Dedicates the Temple at Jerusalem.jpg|thumb|alt=In the foreground, a bearded man dressed in an impressive white robe and head-dress raises his hand to heaven. Behind him, a large crowd bows in prayer.|[[Solomon]] dedicates the [[Temple in Jerusalem|Temple at Jerusalem]] (painting by [[James Tissot]] or follower, c. 1896–1902).]] |

||

The Hebrew Bible gives the impression that the Jerusalem temple was always meant to be the central or even sole temple of Yahweh, but this was not the case.{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} The earliest known Israelite place of worship is a 12th-century BCE open-air altar in the hills of [[Samaria]] featuring a bronze bull reminiscent of Canaanite [[El (deity)#Ugarit and the Levant|Bull-El]] (El in the form of a bull) and the archaeological remains of further temples have been found at [[Dan (ancient city)|Dan]] on Israel's northern border, at [[Tel Arad|Arad]] in the [[Negev]] and [[Tel Be'er Sheva|Beersheba]], both in the territory of Judah.{{sfn|Dever|2003a|p=388}} [[Shiloh (biblical city)|Shiloh]], [[Bethel]], [[Gilgal]], [[Mizpah in Benjamin|Mizpah]], [[Ramah in Benjamin|Ramah]] and Dan were also major sites for festivals, sacrifices, the making of [[Vow#Divine vows|vows]], private rituals, and the adjudication of legal disputes.{{sfn|Bennett|2002|p=83}} |

The Hebrew Bible gives the impression that the Jerusalem temple was always meant to be the central or even sole temple of Yahweh, but this was not the case.{{sfn|Davies|2010|p=112}} The earliest known Israelite place of worship is a 12th-century BCE open-air altar in the hills of [[Samaria]] featuring a bronze bull reminiscent of Canaanite [[El (deity)#Ugarit and the Levant|Bull-El]] (El in the form of a bull) and the archaeological remains of further temples have been found at [[Dan (ancient city)|Dan]] on Israel's northern border, at [[Tel Arad|Arad]] in the [[Negev]] and [[Tel Be'er Sheva|Beersheba]], both in the territory of Judah.{{sfn|Dever|2003a|p=388}} [[Shiloh (biblical city)|Shiloh]], [[Bethel]], [[Gilgal]], [[Mizpah in Benjamin|Mizpah]], [[Ramah in Benjamin|Ramah]] and Dan were also major sites for festivals, sacrifices, the making of [[Vow#Divine vows|vows]], private rituals, and the adjudication of legal disputes.{{sfn|Bennett|2002|p=83}} |

||

===Portrayal=== |

===Portrayal=== |

||

{{ |

{{see also|Aniconism in Judaism}} |

||

Yahweh-worship was thought to be [[aniconic]], meaning that the god was not depicted by a statue or other image. This is not to say that he was not represented in some symbolic form, and early Israelite worship probably focused on [[baetylus|standing stones]], but according to the Biblical texts the temple in Jerusalem featured Yahweh's throne in the form of two [[cherub]]im, their inner wings forming the seat and a box (the [[Ark of the Covenant]]) as a footstool, while the throne itself was empty.{{sfn|Mettinger|2006|pp=288–290}} |

Yahweh-worship was thought to be [[aniconic]], meaning that the god was not depicted by a statue or other image. This is not to say that he was not represented in some symbolic form, and early Israelite worship probably focused on [[baetylus|standing stones]], but according to the Biblical texts the temple in Jerusalem featured Yahweh's throne in the form of two [[cherub]]im, their inner wings forming the seat and a box (the [[Ark of the Covenant]]) as a footstool, while the throne itself was empty.{{sfn|Mettinger|2006|pp=288–290}} |

||

There is no universally accepted explanation for such [[aniconism]], and a number of scholars have argued that Yahweh was in fact represented prior to the reforms of [[Hezekiah]] and [[Josiah]] late in the monarchic period: to quote one study, "[a]n early aniconism, ''[[de facto]]'' or otherwise, is purely a projection of the |

There is no universally accepted explanation for such [[aniconism]], and a number of scholars have argued that Yahweh was in fact represented prior to the reforms of [[Hezekiah]] and [[Josiah]] late in the monarchic period: to quote one study, "[a]n early aniconism, ''[[de facto]]'' or otherwise, is purely a projection of the post-exilic imagination".{{sfn|MacDonald|2007|pp=21, 26–27}} Other scholars argue that there is no certain evidence of any [[anthropomorphic]] representation of Yahweh during the pre-exilic period.{{sfn|Lewis|2020|pp=293–297}} |

||

==Graeco-Roman syncretism== |

==Graeco-Roman syncretism== |

||

Yahweh is frequently invoked in [[Graeco-Roman magic]]al texts dating from the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE, most notably in the [[Greek Magical Papyri]],{{sfn|Betz|1996|p={{page needed|date=August 2020}}}} under the names [[Tetragrammaton|Iao]], [[Adonai]], [[Sabaoth]], and [[Elohim|Eloai]].{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} In these texts, he is often mentioned alongside traditional [[List of Greek mythological figures|Graeco-Roman deities]] and [[List of Egyptian deities|Egyptian deities]].{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} The [[archangels]] [[Michael (archangel)|Michael]], [[Gabriel]], [[Raphael (archangel)|Raphael]], and [[Uriel|Ouriel]] and Jewish [[cultural hero]]es such as [[Abraham]], [[Jacob]], and [[Moses]] are also invoked frequently.{{sfn|Arnold|1996|p={{page needed|date=August 2020}}}} The frequent occurrence of Yahweh's name was likely due to Greek and Roman folk magicians seeking to make their spells more powerful through the invocation of a prestigious foreign deity.{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} |

Yahweh is frequently invoked in [[Graeco-Roman magic]]al texts dating from the 2nd century BCE to the 5th century CE, most notably in the [[Greek Magical Papyri]],{{sfn|Betz|1996|p={{page needed|date=August 2020}}}} under the names [[Tetragrammaton|Iao]], [[Adonai]], [[Sabaoth]], and [[Elohim|Eloai]].{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} In these texts, he is often mentioned alongside traditional [[List of Greek mythological figures|Graeco-Roman deities]] and [[List of Egyptian deities|Egyptian deities]].{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} The [[archangels]] [[Michael (archangel)|Michael]], [[Gabriel]], [[Raphael (archangel)|Raphael]], and [[Uriel|Ouriel]] and Jewish [[cultural hero]]es such as [[Abraham]], [[Jacob]], and [[Moses]] are also invoked frequently.{{sfn|Arnold|1996|p={{page needed|date=August 2020}}}} The frequent occurrence of Yahweh's name was likely due to Greek and Roman folk magicians seeking to make their spells more powerful through the invocation of a prestigious foreign deity.{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996b|pp=242–256}} |

||

A coin issued by [[Pompey]] to celebrate his successful [[Siege of Jerusalem (63 BC)|conquest of Judaea]] showed a kneeling, bearded figure grasping a branch (a common Roman symbol of submission) subtitled ''BACCHIVS IVDAEVS'', which may be translated as either "The Jewish [[Bacchus]]" or "Bacchus the Judaean". The figure has been interpreted as depicting Yahweh as a local variety of Bacchus, that is, [[Dionysus]].{{sfn|Scott|2015|pp=169–172}} However, as coins minted with such iconography ordinarily depicted subjected persons, and not the gods of a subjected people, some have assumed the coin simply depicts the surrender of a Judean who was called "Bacchius", sometimes identified as the Hasmonean king [[Aristobulus II]], who was overthrown by Pompey's campaign.{{sfn|Scott|2015|pp=11, 16, 80, 126}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Levine |first=Lee I. |title=Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence? |date=1998 |publisher=University of Washington Press |isbn=978-0-295-97682-2 |pages=38–60 |jstor=j.ctvcwnpvs |language=en-us}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lane |first=Eugene N. |date=November 1979 |title=Sabazius and the Jews in Valerius Maximus: a Re-examination |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-roman-studies/article/abs/sabazius-and-the-jews-in-valerius-maximus-a-reexamination/9A146A478B7D4B7F239ED7AE321C2F34 |journal=The Journal of Roman Studies |language=en |volume=69 |pages=35–38 |doi=10.2307/299057 |jstor=299057 |s2cid=163401482 |issn=1753-528X}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Harlan |first=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YztmAAAAMAAJ |title=Roman Republican Moneyers and Their Coins, 63 B.C.–49 B.C. |publisher=Seaby |year=1995 |isbn=0-7134-7672-9 |pages=115–118 |language=en-us}}</ref> |

A coin issued by [[Pompey]] to celebrate his successful [[Siege of Jerusalem (63 BC)|conquest of Judaea]] showed a kneeling, bearded figure grasping a branch (a common Roman symbol of submission) subtitled ''BACCHIVS IVDAEVS'', which may be translated as either "The Jewish [[Bacchus]]" or "Bacchus the Judaean". The figure has been interpreted as depicting Yahweh as a local variety of Bacchus, that is, [[Dionysus]].{{sfn|Scott|2015|pp=169–172}} However, as coins minted with such iconography ordinarily depicted subjected persons, and not the gods of a subjected people, some have assumed the coin simply depicts the surrender of a Judean who was called "Bacchius", sometimes identified as the Hasmonean king [[Aristobulus II]], who was overthrown by Pompey's campaign.{{sfn|Scott|2015|pp=11, 16, 80, 126}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Levine |first=Lee I. |title=Judaism and Hellenism in Antiquity: Conflict or Confluence? |date=1998 |publisher=University of Washington Press |isbn=978-0-295-97682-2 |pages=38–60 |jstor=j.ctvcwnpvs |language=en-us}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lane |first=Eugene N. |date=November 1979 |title=Sabazius and the Jews in Valerius Maximus: a Re-examination |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-roman-studies/article/abs/sabazius-and-the-jews-in-valerius-maximus-a-reexamination/9A146A478B7D4B7F239ED7AE321C2F34 |journal=The Journal of Roman Studies |language=en |volume=69 |pages=35–38 |doi=10.2307/299057 |jstor=299057 |s2cid=163401482 |issn=1753-528X}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Harlan |first=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YztmAAAAMAAJ |title=Roman Republican Moneyers and Their Coins, 63 B.C.–49 B.C. |publisher=Seaby |year=1995 |isbn=0-7134-7672-9 |pages=115–118 |language=en-us}}</ref> |

||

In any event, [[Tacitus]], [[John the Lydian]], [[Cornelius Labeo]], and [[Marcus Terentius Varro]] similarly identify Yahweh with Bacchus–Dionysus.{{sfn|McDonough|1999|page=88}} Jews themselves frequently used symbols that were also associated with Dionysus such as [[kylix]]es, [[amphora]]e, leaves of [[ivy]], and clusters of [[grapes]], a similarity [[Plutarch]] used to argue that Jews worshipped a [[Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)|hypostasized]] form of Bacchus–Dionysus.{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996a|page=233}} In his ''[[Moralia|Quaestiones Convivales]]'', Plutarch further notes that the Jews hail their god with cries of "[[wikt:euoi|Euoi]]" and "[[Sabazios|Sabi]]", phrases associated with the worship of Dionysus.{{sfn|Plutarch|n.d.|loc=[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0007.tlg112.perseus-eng1:4.6 "Question VI"]}}{{sfn|McDonough|1999|page=89}}{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996a|pages=232–233}} According to [[Sean M. McDonough]], Greek speakers may have confused [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]] words such as [[Sabbath]], [[Alleluia]], or even possibly some variant of the name Yahweh itself, for more familiar terms associated with Dionysus.{{sfn|McDonough|1999|pages=89–90}} |

In any event, [[Tacitus]], [[John the Lydian]], [[Cornelius Labeo]], and [[Marcus Terentius Varro]] similarly identify Yahweh with Bacchus–Dionysus.{{sfn|McDonough|1999|page=88}} Jews themselves frequently used symbols that were also associated with Dionysus such as [[kylix]]es, [[amphora]]e, leaves of [[ivy]], and clusters of [[grapes]], a similarity [[Plutarch]] used to argue that Jews worshipped a [[Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)|hypostasized]] form of Bacchus–Dionysus.{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996a|page=233}} In his ''[[Moralia|Quaestiones Convivales]]'', Plutarch further notes that the Jews hail their god with cries of "[[wikt:euoi|Euoi]]" and "[[Sabazios|Sabi]]", phrases associated with the worship of Dionysus.{{sfn|Plutarch|n.d.|loc=[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0007.tlg112.perseus-eng1:4.6 "Question VI"]}}{{sfn|McDonough|1999|page=89}}{{sfn|Smith|Cohen|1996a|pages=232–233}} According to [[Sean M. McDonough]], Greek speakers may have confused [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]] words such as [[Sabbath]], [[Alleluia]], or even possibly some variant of the name Yahweh itself, for more familiar terms associated with Dionysus.{{sfn|McDonough|1999|pages=89–90}} |

||

Other Roman writers, such as [[Juvenal]], [[Petronius]], and [[Florus]], identified Yahweh with the god [[Caelus]].<ref>[[Juvenal]], ''Satires'' 14.97; Peter Schäfer, ''Judeophobia: Attitudes toward the Jews in the Ancient World'' (Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 41, 79–80.</ref><ref>[[Petronius]], frg. 37.2; Schäfer, ''Judeophobia'', pp. 77–78.</ref><ref>[[Florus]], ''Epitome'' 1.40 (3.5.30): "The Jews tried to defend [[Jerusalem]]; but he ''[Pompeius Magnus]'' entered this city also and saw that grand Holy of Holies of an impious people exposed, Caelum under a golden vine" ''(Hierosolymam defendere temptavere Iudaei; verum haec quoque et intravit et vidit illud grande inpiae gentis arcanum patens, sub aurea vite Caelum).'' Finbarr Barry Flood, ''The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture'' (Brill, 2001), pp. 81 and 83 (note 118). The ''[[Oxford Latin Dictionary]]'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 252, entry on ''caelum'', cites Juvenal, Petronius, and Florus as examples of ''Caelus'' or ''Caelum'' "with reference to [[Jehovah]]; also, to some symbolization of Jehovah."</ref> |

Other Roman writers, such as [[Juvenal]], [[Petronius]], and [[Florus]], identified Yahweh with the god [[Caelus]].<ref>[[Juvenal]], ''Satires'' 14.97; Peter Schäfer, ''Judeophobia: Attitudes toward the Jews in the Ancient World'' (Harvard University Press, 1997), pp. 41, 79–80.</ref><ref>[[Petronius]], frg. 37.2; Schäfer, ''Judeophobia'', pp. 77–78.</ref><ref>[[Florus]], ''Epitome'' 1.40 (3.5.30): "The Jews tried to defend [[Jerusalem]]; but he ''[Pompeius Magnus]'' entered this city also and saw that grand Holy of Holies of an impious people exposed, Caelum under a golden vine" ''(Hierosolymam defendere temptavere Iudaei; verum haec quoque et intravit et vidit illud grande inpiae gentis arcanum patens, sub aurea vite Caelum).'' Finbarr Barry Flood, ''The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture'' (Brill, 2001), pp. 81 and 83 (note 118). The ''[[Oxford Latin Dictionary]]'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, 1985 reprinting), p. 252, entry on ''caelum'', cites Juvenal, Petronius, and Florus as examples of ''Caelus'' or ''Caelum'' "with reference to [[Jehovah]]; also, to some symbolization of Jehovah."</ref> |

||

| Line 183: | Line 184: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Ahlström |

|last = Ahlström |

||

|first = Gösta Werner |

|first = Gösta Werner |

||

|chapter = The Role of Archaeological and Literary Remains in Reconstructing Israel's History |

|chapter = The Role of Archaeological and Literary Remains in Reconstructing Israel's History |

||

| Line 194: | Line 195: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-567-49110-7 |

|isbn = 978-0-567-49110-7 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|title = The Oxford Handbook of Isaiah |

|title = The Oxford Handbook of Isaiah |

||

|last = Albani |

|last = Albani |

||

|first = Matthias |

|first = Matthias |

||

|publisher = Oxford University Press |

|publisher = Oxford University Press |

||

|year = 2020 |

|year = 2020 |

||

|isbn = 978-0-19-066924-9 |

|isbn = 978-0-19-066924-9 |

||

|pages = 219–248 |

|pages = 219–248 |

||

|editor-last = Tiemeyer |

|editor-last = Tiemeyer |

||

|editor-first = Lena-Sofia |

|editor-first = Lena-Sofia |

||

|chapter = Monotheism in Isaiah |

|chapter = Monotheism in Isaiah |

||

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ZDmWzQEACAAJ&pg=PA219 |

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ZDmWzQEACAAJ&pg=PA219 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 228: | Line 229: | ||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Allen |

|last = Allen |

||

|first = Spencer L. |

|first = Spencer L. |

||

|title = The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East |

|title = The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East |

||

|publisher = Walter de Gruyter |

|publisher = Walter de Gruyter |

||

|year = 2015 |

|year = 2015 |

||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ou9eCAAAQBAJ |

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ou9eCAAAQBAJ |

||

|isbn = 978-1-5015-0022-0 |

|isbn = 978-1-5015-0022-0 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Alter |

|last = Alter |

||

|first = Robert |

|first = Robert |

||

|publisher = W. W. Norton |

|publisher = W. W. Norton |

||

|year = 2018 |

|year = 2018 |

||

|title = The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (Volume 3) |

|title = The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (Volume 3) |

||

| Line 265: | Line 266: | ||

|first=Margaret |

|first=Margaret |

||

|author-link=Margaret Barker |

|author-link=Margaret Barker |

||

|title=The Great Angel: A Study of Israel's Second God |

|title=The Great Angel: A Study of Israel's Second God |

||

|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |

|publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |

||

|year=1992 |

|year=1992 |

||

|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=y63GE5Tw3KMC |

|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=y63GE5Tw3KMC |

||

|isbn=978-0-664-25395-0 |

|isbn=978-0-664-25395-0 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 277: | Line 278: | ||

|series=The Mother of the Lord |

|series=The Mother of the Lord |

||

|volume=1 |

|volume=1 |

||

|title=The Lady in the Temple |

|title=The Lady in the Temple |

||

|publisher=Bloomsbury T&T Clark |

|publisher=Bloomsbury T&T Clark |

||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j1smp_frb6cC |

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j1smp_frb6cC |

||

|isbn=978-0-567-36246-9 |

|isbn=978-0-567-36246-9 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 290: | Line 291: | ||

|title = Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah |

|title = Only One God?: Monotheism in Ancient Israel and the Veneration of the Goddess Asherah |

||

|publisher = A&C Black |

|publisher = A&C Black |

||

|year = 2001 |

|year = 2001 |

||

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=eMneBAAAQBAJ&q=Only+One+God&pg=PA189 |

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=eMneBAAAQBAJ&q=Only+One+God&pg=PA189 |

||

|isbn = 978-0-567-23212-0 |

|isbn = 978-0-567-23212-0 |

||

| Line 303: | Line 304: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-8028-3909-1 |

|isbn = 978-0-8028-3909-1 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Ben-Sasson |

|last = Ben-Sasson |

||

|first = Hillel |

|first = Hillel |

||

| Line 385: | Line 386: | ||

|editor-link1 = Louis Finkelstein |

|editor-link1 = Louis Finkelstein |

||

|editor2-last = Davies |

|editor2-last = Davies |

||

|editor2-first = W. D. |

|editor2-first = W. D. |

||

|editor3-last = Horbury |

|editor3-last = Horbury |

||

|editor3-first = William |

|editor3-first = William |

||

|title = The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3, The Early Roman Period |

|title = The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 3, The Early Roman Period |

||

|publisher = Cambridge University Press |

|publisher = Cambridge University Press |

||

| Line 406: | Line 407: | ||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last1 = Coogan |

|last1 = Coogan |

||

|first1 = Michael D. |

|first1 = Michael D. |

||

|last2 = Brettler |

|last2 = Brettler |

||

|first2 = Marc Zvi |

|first2 = Marc Zvi |

||

|last3 = Newsom |

|last3 = Newsom |

||

|first3 = Carol Ann |

|first3 = Carol Ann |

||

|chapter = Editors' Introduction |

|chapter = Editors' Introduction |

||

|editor1-last = Coogan |

|editor1-last = Coogan |

||

|editor1-first = Michael David |

|editor1-first = Michael David |

||

|editor2-last = Brettler |

|editor2-last = Brettler |

||

|editor2-first = Marc Zvi |

|editor2-first = Marc Zvi |

||

|editor3-last = Newsom |

|editor3-last = Newsom |

||

|editor3-first = Carol Ann |

|editor3-first = Carol Ann |

||

|title = The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books |

|title = The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books |

||

|publisher = Oxford University Press |

|publisher = Oxford University Press |

||

|year = 2007 |

|year = 2007 |

||

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Nc-i_pQsiW8C&pg=PA7 |

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Nc-i_pQsiW8C&pg=PA7 |

||

|isbn = 978-0-19-528880-3 |

|isbn = 978-0-19-528880-3 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

| Line 594: | Line 595: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-521-77248-8 |

|isbn = 978-0-521-77248-8 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|title = Yahweh before Israel: Glimpses of History in a Divine Name |

|title = Yahweh before Israel: Glimpses of History in a Divine Name |

||

|last = Fleming |

|last = Fleming |

||

| Line 604: | Line 605: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |title=From Mari to Jerusalem and Back: Assyriological and Biblical Studies in Honor of Jack Murad Sasson |last=Fleming |first=Daniel E. |publisher=Eisenbrauns |year=2020b |isbn=978-1-57506-741-4 |editor-last=Azzoni |editor-first=Annalisa |chapter=The Name YhwꜢ as a People: Reconsidering the Amorite Evidence |editor-last2=Kleinerman |editor-first2=Alexandra |editor-last3=Knight |editor-first3=Douglas A. |editor-last4=Owen |editor-first4=David I. |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/100704584}} |

* {{cite book |title=From Mari to Jerusalem and Back: Assyriological and Biblical Studies in Honor of Jack Murad Sasson |last=Fleming |first=Daniel E. |publisher=Eisenbrauns |year=2020b |isbn=978-1-57506-741-4 |editor-last=Azzoni |editor-first=Annalisa |chapter=The Name YhwꜢ as a People: Reconsidering the Amorite Evidence |editor-last2=Kleinerman |editor-first2=Alexandra |editor-last3=Knight |editor-first3=Douglas A. |editor-last4=Owen |editor-first4=David I. |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/100704584}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|title = A Story of YHWH: Cultural Translation and Subversive Reception in Israelite History |

|title = A Story of YHWH: Cultural Translation and Subversive Reception in Israelite History |

||

|last = Flynn |

|last = Flynn |

||

| Line 679: | Line 680: | ||

|first = Frank H. Jr. |

|first = Frank H. Jr. |

||

|chapter = Feasts, Festivals |

|chapter = Feasts, Festivals |

||

|editor1-last = Freedman |

|editor1-last = Freedman |

||

|editor1-first = David Noel |

|editor1-first = David Noel |

||

|editor2-last = Myers |

|editor2-last = Myers |

||

|editor2-first = Allen C. |

|editor2-first = Allen C. |

||

|title = Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |

|title = Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |

||

|publisher = Amsterdam University Press |

|publisher = Amsterdam University Press |

||

| Line 691: | Line 692: | ||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Grabbe |

|last = Grabbe |

||

|first = Lester L. |

|first = Lester L. |

||

|title = An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism |

|title = An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism |

||

|publisher = A&C Black |

|publisher = A&C Black |

||

|year = 2010 |

|year = 2010 |

||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=i89-9fdNUcAC&pg=PA2 |

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=i89-9fdNUcAC&pg=PA2 |

||

|isbn = 978-0-567-55248-8 |

|isbn = 978-0-567-55248-8 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

| Line 773: | Line 774: | ||

|chapter = God, Names of |

|chapter = God, Names of |

||

|editor1-last = Mills |

|editor1-last = Mills |

||

|editor1-first = Watson E. |

|editor1-first = Watson E. |

||

|editor2-last = Bullard |

|editor2-last = Bullard |

||

|editor2-first = Roger Aubrey |

|editor2-first = Roger Aubrey |

||

| Line 793: | Line 794: | ||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OtOhypZz_pEC&pg=PAxxiii |

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OtOhypZz_pEC&pg=PAxxiii |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{Cite journal |

* {{Cite journal |

||

|title=The Verb *yahway |

|title=The Verb *yahway |

||

|journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |

|journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |

||

|last=Kitz |

|last=Kitz |

||

|first=Anne Marie |

|first=Anne Marie |

||

|issue=1 |

|issue=1 |

||

|volume=138 |

|volume=138 |

||

|pages=39–62 |

|pages=39–62 |

||

|doi=10.15699/jbl.1381.2019.508716 |

|doi=10.15699/jbl.1381.2019.508716 |

||

|year=2019 |

|year=2019 |

||

|issn=0021-9231 |

|issn=0021-9231 |

||

|url=https://www.academia.edu/90528116 |

|url=https://www.academia.edu/90528116 |

||

| Line 925: | Line 926: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-664-21262-9 |

|isbn = 978-0-664-21262-9 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|title = Yahweh: Origin of a Desert God |

|title = Yahweh: Origin of a Desert God |

||

|last = Miller II |

|last = Miller II |

||

| Line 1,001: | Line 1,002: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-8028-2417-2 |

|isbn = 978-0-8028-2417-2 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite journal |

* {{cite journal |

||

|title = On Deserted Landscapes and Divine Iconography: Iconographic Perspectives on the Origins of YHWH |

|title = On Deserted Landscapes and Divine Iconography: Iconographic Perspectives on the Origins of YHWH |

||

|journal = Entangled Religions |

|journal = Entangled Religions |

||

| Line 1,022: | Line 1,023: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-674-50497-4 |

|isbn = 978-0-674-50497-4 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

*{{cite journal |title=Yahweh Becomes King |first=Roy A. |last=Rosenberg |journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |volume=85 |issue=3 |date=1966 |pages=297–307 |publisher=The Society of Biblical Literature |doi=10.2307/3264243 |jstor=3264243 }} |

* {{cite journal |title=Yahweh Becomes King |first=Roy A. |last=Rosenberg |journal=Journal of Biblical Literature |volume=85 |issue=3 |date=1966 |pages=297–307 |publisher=The Society of Biblical Literature |doi=10.2307/3264243 |jstor=3264243 }} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Schniedewind |

|last = Schniedewind |

||

| Line 1,090: | Line 1,091: | ||

|editor2-last = Walker |

|editor2-last = Walker |

||

|editor2-first = Joel |

|editor2-first = Joel |

||

|title = Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World |

|title = Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World |

||

|publisher = Penn State Press |

|publisher = Penn State Press |

||

|year = 2003 |

|year = 2003 |

||

| Line 1,106: | Line 1,107: | ||

|isbn = 978-3-16-149543-4 |

|isbn = 978-3-16-149543-4 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last = Smith |

|last = Smith |

||

|first = Mark S. |

|first = Mark S. |

||

|author-link = Mark S. Smith |

|author-link = Mark S. Smith |

||

|chapter = Monotheism and the Redefinition of Divinity in Ancient Israel |

|chapter = Monotheism and the Redefinition of Divinity in Ancient Israel |

||

|editor-last = Niditch |

|editor-last = Niditch |

||

|editor-first = Susan |

|editor-first = Susan |

||

|title = The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel |

|title = The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel |

||

|publisher = John Wiley & Sons |

|publisher = John Wiley & Sons |

||

|year = 2016 |

|year = 2016 |

||

|isbn = 978-0-470-65677-8 |

|isbn = 978-0-470-65677-8 |

||

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=-eMACgAAQBAJ&pg=PA278 |

|chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=-eMACgAAQBAJ&pg=PA278 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 1,142: | Line 1,143: | ||

|chapter = Jewish Religious Life in the Persian Period |

|chapter = Jewish Religious Life in the Persian Period |

||

|editor1-last = Finkelstein |

|editor1-last = Finkelstein |

||

|editor1-first = Louis |

|editor1-first = Louis |

||

|title = The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 1, Introduction: The Persian Period |

|title = The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 1, Introduction: The Persian Period |

||

|publisher = Cambridge University Press |

|publisher = Cambridge University Press |

||

| Line 1,151: | Line 1,152: | ||

* {{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Morton|last2=Cohen|first2=Shaye J. D.|date=1996a|title=Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume One: Studies in Historical Method, Ancient Israel, Ancient Judaism|publisher=E. J. Brill |location=Leiden, The Netherlands, New York, and Cologne|isbn=978-90-04-10477-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EyfB19u1U8EC}} |

* {{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Morton|last2=Cohen|first2=Shaye J. D.|date=1996a|title=Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume One: Studies in Historical Method, Ancient Israel, Ancient Judaism|publisher=E. J. Brill |location=Leiden, The Netherlands, New York, and Cologne|isbn=978-90-04-10477-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EyfB19u1U8EC}} |

||

* {{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Morton|last2=Cohen|first2=Shaye J. D.|date=1996b|title=Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume Two: New Testament, Christianity, and Magic|publisher=Brill|location=Leiden, The Netherlands, New York, and Cologne|isbn=978-90-04-10479-2}} |

* {{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Morton|last2=Cohen|first2=Shaye J. D.|date=1996b|title=Studies in the Cult of Yahweh: Volume Two: New Testament, Christianity, and Magic|publisher=Brill|location=Leiden, The Netherlands, New York, and Cologne|isbn=978-90-04-10479-2}} |

||

*{{cite book | last=Sommer | first=Benjamin D. | title=The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=2009 | isbn=978-0-521-51872-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3T9eWJuM7EcC&pg=PA145 }} |

* {{cite book | last=Sommer | first=Benjamin D. | title=The Bodies of God and the World of Ancient Israel | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=2009 | isbn=978-0-521-51872-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3T9eWJuM7EcC&pg=PA145 }} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|last1 = Sommer |

|last1 = Sommer |

||

| Line 1,187: | Line 1,188: | ||

|isbn = 978-0-19-513937-2 |

|isbn = 978-0-19-513937-2 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |

* {{cite book |

||

|title = The "God of Israel" in History and Tradition |

|title = The "God of Israel" in History and Tradition |

||

|last = Stahl |

|last = Stahl |

||

|first = Michael J. |

|first = Michael J. |

||

|publisher = BRILL |

|publisher = BRILL |

||

|year = 2021 |

|year = 2021 |

||

|isbn = 978-90-04-44772-1 |

|isbn = 978-90-04-44772-1 |

||

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=drMlEAAAQBAJ |

|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=drMlEAAAQBAJ |

||

|series = Vetus Testamentum, Supplements |

|series = Vetus Testamentum, Supplements |

||

|volume = 187 |

|volume = 187 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 1,208: | Line 1,209: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Stone |first=Robert E. II |chapter=I Am Who I Am |editor1-last=Freedman |editor1-first=David Noel |editor2-last=Myers |editor2-first=Allen C. |title=Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |publisher=Eerdmans |year=2000 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&q=i+am |isbn=978-90-5356-503-2}} |

* {{cite book |last=Stone |first=Robert E. II |chapter=I Am Who I Am |editor1-last=Freedman |editor1-first=David Noel |editor2-last=Myers |editor2-first=Allen C. |title=Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible |publisher=Eerdmans |year=2000 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qRtUqxkB7wkC&q=i+am |isbn=978-90-5356-503-2}} |

||

* {{cite journal |

* {{cite journal |

||

|title = El extraño caso del dios Qos. ¿Por qué la deidad edomita/idumea no es mencionada en la Biblia? |