Tell al-Rimah: Difference between revisions

Ploversegg (talk | contribs) →Further reading: add online reflink |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

| notes = |

| notes = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Tell al-Rimah''' (also Tell ar-Rimah) is an archaeological settlement mound, in [[Nineveh Province]] ([[Iraq]]) roughly {{convert|50|mi|order=flip}} west of [[Mosul]] and ancient [[Nineveh]] in the [[Sinjar]] region. It lies 15 kilometers south of the site of [[Tal Afar]]. |

'''Tell al-Rimah''' (also Tell ar-Rimah) is an archaeological settlement mound, in [[Nineveh Province]] ([[Iraq]]) roughly {{convert|50|mi|order=flip}} west of [[Mosul]] and ancient [[Nineveh]] in the [[Sinjar]] region. It lies 15 kilometers south of the site of [[Tal Afar]]. |

||

It has been proposed that its ancient name in the 2nd Millennium BC was Karana or Qattara or Razama. Karana and Qattara were very close together and thought to be part of a small kingdom.<ref>Charpin, Dominique, and Jean-Marie Durand, "Le nom antique de Tell Rimāh", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 125–46, 1987</ref> It has also been suggested that the site's name in the 1st Millennium BC was Zamaḫâ. It is near the circular walled similar archaeological sites of Tell Hadheil, a large Early Dynastic site with Old Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian occupation, and Tell Huweish. Tell Hamira, known earlier as Tell Abu Hamira, is 16 kilometers to the east and has also been suggested as the site of Karana. |

|||

Currently, archaeology leans toward Qattara as the ancient name of Tell Al-Rimah.<ref>Nashef, Khaled, "Qaṭṭarā and Karanā", Die Welt Des Orients, vol. 19, 1988, pp. 35–39, 1988</ref> |

|||

==Archaeology== |

==Archaeology== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The site covers an area roughly 500 meters by 500 meters, surrounded by a polygonal city wall. The interior holds a number of low mounds and a large central mound 30 meters high and 100 meters in diameter.<ref>[https://findit.library.yale.edu/images_layout/view?parentoid=15763254&increment=120]David Oates, "Excavations at Tell al Rimah A Summary Report", Sumer, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 69-78, 1963</ref> |

The site covers an area roughly 500 meters by 500 meters, surrounded by a polygonal city wall. The interior holds a number of low mounds and a large central mound 30 meters high and 100 meters in diameter.<ref>[https://findit.library.yale.edu/images_layout/view?parentoid=15763254&increment=120]David Oates, "Excavations at Tell al Rimah A Summary Report", Sumer, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 69-78, 1963</ref> |

||

| Line 53: | Line 56: | ||

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period [[faience]] rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".<ref>Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021</ref> |

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period [[faience]] rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".<ref>Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The most notable artifact found was the stele of [[Adad-nirari III]] (811 to 783 BC), known as the [[Tell al-Rimah stela]], which may mention an early king of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Northern Israel]] stating "He received the tribute of Ia'asu the Samaritan, of the Tyrian (ruler) and of the Sidonian (ruler)" and contains the first cuneiform mention of [[Samaria]] by that name. On the side of the stele was an inscription of Nergal-ereš, who names himself "governor of Raṣappa".<ref>Page, Stephanie, "A Stela of Adad-Nirari III and Nergal-Ereš from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 139–53, 1968</ref><ref>Shea, William H., "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 101–13, 1978</ref><ref>Parpola, Simo, "The Location of Raṣappa", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 393-412, 2017</ref> It has been suggested, based on the stele, that Tell al-Rimah has called Zamaḫâ at that time.<ref>May, Natalie N., "“The True Image of the God…:” Adoration of the King’s Image, Assyrian Imperial Cult and Territorial Control", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 185-240, 2020</ref> A larger version of this stele was found at [[Dūr-Katlimmu]].<ref>Radner, Karen, "The Stele of Adad-nērārī III and Nergal-ēreš from Dūr-Katlimmu (Tell Šaiḫ Ḥamad)", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 265-277, 2012</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| Line 67: | Line 68: | ||

[[File:Luxury tableware - Upper Mesopotamia LBA.jpg|thumb|Luxury tableware - Upper Mesopotamia LBA]] |

[[File:Luxury tableware - Upper Mesopotamia LBA.jpg|thumb|Luxury tableware - Upper Mesopotamia LBA]] |

||

[[File:Marble column from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, Neo-Assyrian period. Iraq Museum.jpg|thumb|Marble column from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, Neo-Assyrian period. Iraq Museum]] |

[[File:Marble column from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, Neo-Assyrian period. Iraq Museum.jpg|thumb|Marble column from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq, Neo-Assyrian period. Iraq Museum]] |

||

In the Middle Bronze period the site experienced widespread destruction and was abandoned before being re-occupied in the Late Bronze period. In the [[Mitanni]] period that followed the Old Babylonian occupation Karana is frequently mentioned in tablets found at the trading city of [[Nuzi]] and two Nuzi type tablets were found at Karana. The city was no longer fortified at that time but appears to have been quite prosperous. Another period of abandonment then occurred, followed by re-occupation on a much smaller scale in Neo-Assyrian times.<ref>Dalley, Stephanie, "The Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 179-207, 2002 {{ISBN|1-931956-02-2}}</ref> |

In the Middle Bronze period the site experienced widespread destruction and was abandoned before being re-occupied in the Late Bronze period. In the [[Mitanni]] period that followed the Old Babylonian occupation Karana is frequently mentioned in tablets found at the trading city of [[Nuzi]] and two Nuzi type tablets were found at Karana. The city was no longer fortified at that time but appears to have been quite prosperous. Another period of abandonment then occurred, followed by re-occupation on a much smaller scale in Neo-Assyrian times.<ref>Dalley, Stephanie, "The Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 179-207, 2002 {{ISBN|1-931956-02-2}}</ref> |

||

A notable find was a large archive of letters of [[Iltani]], daughter of Samu-Addu, king of Karana from the Old Babylonian period. The archive covers about a four year period and amounts to about 200 tablets.<ref>Jesper Eidem, "Some Remarks on the Iltani Archive from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 51, pp. 67–78, 1989</ref><ref>[http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/129784/1/9788491682387%20(Creative%20Commons).pdf#page=139] Langlois, Anne-Isabelle, "“You Had None of a Woman’s Compassion”: Princess Iltani from her Archive Uncovered at Tell al-Rimah (18th Century BCE)", Gender and methodology in the ancient Near East: Approaches from Assyriology and beyond 10, 2018</ref> It is known she had at least two sons, one named Yasitna-abum and a sister in Assur.<ref>Stol, Marten, "The court and the harem before 1500 BC", Women in the Ancient Near East, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 459-511, 2016</ref> |

A notable find was a large archive of letters of [[Iltani]], daughter of Samu-Addu, king of Karana from the Old Babylonian period. The archive covers about a four year period and amounts to about 200 tablets.<ref>Jesper Eidem, "Some Remarks on the Iltani Archive from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 51, pp. 67–78, 1989</ref><ref>[http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/bitstream/2445/129784/1/9788491682387%20(Creative%20Commons).pdf#page=139] Langlois, Anne-Isabelle, "“You Had None of a Woman’s Compassion”: Princess Iltani from her Archive Uncovered at Tell al-Rimah (18th Century BCE)", Gender and methodology in the ancient Near East: Approaches from Assyriology and beyond 10, 2018</ref> It is known she had at least two sons, one named Yasitna-abum and a sister in Assur.<ref>Stol, Marten, "The court and the harem before 1500 BC", Women in the Ancient Near East, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 459-511, 2016</ref> |

||

| Line 88: | Line 89: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

Ashkur-Addu then deposed Hatnu-rapi, who fled to Mari. A clay sealing read "Bini-sakin, foremost son of the king, servant of Askur-Addu". A messenger text found at Karana "They have brought in four tablets of the governor of Susa in Elam.... I opened those tablets... but there was no news in them" showed the wide regional interconnections at this time. Aqba-hammu then deposed Ashkur-Addu and became a vassal of Hammurabi |

Ashkur-Addu then deposed Hatnu-rapi, who fled to Mari. A clay sealing read "Bini-sakin, foremost son of the king, servant of Askur-Addu". A messenger text found at Karana "They have brought in four tablets of the governor of Susa in Elam.... I opened those tablets... but there was no news in them" showed the wide regional interconnections at this time. Aqba-hammu then deposed Ashkur-Addu and became a vassal of Hammurabi. |

||

===Iron Age=== |

===Iron Age=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

====Neo-Assyrian Period==== |

====Neo-Assyrian Period==== |

||

The site was lightly occupation in the later Iron Age [[Neo-Assyrian]] period |

The site was lightly occupation in the later Iron Age [[Neo-Assyrian]] period. |

||

| ⚫ | The most notable artifact found was the stele of [[Adad-nirari III]] (811 to 783 BC), known as the [[Tell al-Rimah stela]], which may mention an early king of [[Kingdom of Israel (Samaria)|Northern Israel]] stating "He received the tribute of Ia'asu the Samaritan, of the Tyrian (ruler) and of the Sidonian (ruler)" and contains the first cuneiform mention of [[Samaria]] by that name. On the side of the stele was an inscription of Nergal-ereš, who names himself "governor of Raṣappa".<ref>Page, Stephanie, "A Stela of Adad-Nirari III and Nergal-Ereš from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 139–53, 1968</ref><ref>Shea, William H., "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 101–13, 1978</ref><ref>Parpola, Simo, "The Location of Raṣappa", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 393-412, 2017</ref> It has been suggested, based on the stele, that Tell al-Rimah has called Zamaḫâ at that time.<ref>May, Natalie N., "“The True Image of the God…:” Adoration of the King’s Image, Assyrian Imperial Cult and Territorial Control", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 185-240, 2020</ref> A larger version of this stele was found at [[Dūr-Katlimmu]].<ref>Radner, Karen, "The Stele of Adad-nērārī III and Nergal-ēreš from Dūr-Katlimmu (Tell Šaiḫ Ḥamad)", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 265-277, 2012</ref> |

||

==Razama== |

|||

Razama (ra-za-ma-a<sup>ki</sup>) was an ancient Near East city which achieved prominence in the |

|||

Old Babylonian period and was capital of the land of Yussan/Yassan. It is currently unlocated. A complication is that there were two cities of this name in that period.<ref>[https://urkesh.org/attach/Goetze1953a.pdf]Goetze, Albrecht, "An Old Babylonian Itinerary", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 7.2, pp. 51-72, 1953</ref> It is known that at |

|||

one point the chief archivist at Razama, appointed by [[Shamshi-Adad I]], |

|||

was a Sîn-iddinam.<ref>Koliński, Rafał, "The Fate of Yasmaḫ-Addu, the King of Mari", Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014, edited by Olga Drewnowska and Malgorzata Sandowicz, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 221-236, 2017</ref> Their is an unpublished treaty between Mutlya of Apum and Hazip-Tessup of Razamä.<ref>Beckman, Gary, "Hittite Treaties and the Development of the Cuneiform Treaty Tradition", Die deuteronomistischen Geschichtswerke: Redaktions- und religionsgeschichtliche Perspektiven zur "Deuteronomismus"-Diskussion in Tora und Vorderen Propheten, edited by Jan Christian Gertz, Doris Prechel, Konrad Schmid and Markus Witte, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 279-302, 2006</ref> The city was |

|||

briefly controlled by [[Ishme-Dagan I]], ruler of Isin, after attacking it with |

|||

the assistance of Eshnunna, before it was recaptured by Zimri-Lim.<ref>Beitzel, Barry J., "Išme-Dagan’s Military Actions in the Jezirah: A Geographical Study", Iraq, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 29–42, 1984</ref> |

|||

A text found at [[Tell Leilan]] (Subat-Enlil) mentions a Hurrian prince of the Razama, Hazip-Tessup.<ref>Salvini, Mirjo, "The earliest evidences of the Hurrians before the formation of the reign of Mittanni", Urkesh and the Hurrians Studies in Honor of Lloyd Cotsen, Urkesh/Mozan Studies Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. Malibu: Undena Publications, pp. 99-115, 1998</ref> A tablet found at [[Me-Turan]] carried a year |

|||

name of Silli-Sin, a ruler of Eshnunna who was a contemporary of Hammurabi, "Year Razama was smitten by weapons".<ref>Muhamed, Ahmad Kamil, "Old Babylonian Cuneiform Texts from the Hamrin Basin: Tell Hadad", Edubba, vol. 1. London: NABU, 1992</ref> |

|||

Razama is mentioned in several texts found at the site of [[Mari, Syria|Mari]]. In |

|||

the 10th regnal year of Mari ruler [[Zimri-Lim]] (c. 18th century BC) an army |

|||

led by Atamrum, king of Allahad and later of [[Andarig]] to attack Razama which |

|||

was ruled by Šarriya/Šarraya (Sharrum-kima-kalima), a vassal of Zimri-Lim. The army consisted of troops from [[Eshnunna]] and Elam.<ref>Charpin, D. – Ziegler, N., "Mari et le Proche-Orient à l’époque amorrite", Essai d’histoire politique (FM V), Paris, 2003</ref><ref>Heimpel, W., "Letters to the King of Mari", Winona Lake, 2003</ref><ref>Archi, Alfonso, "Men at War in the Ebla Period: On the Unevenness of the written Documentation", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 262-291, 2015</ref> There was a long, and unsuccessful siege of the city. The defenders practiced a strategy of active defense "When troops arrived at Razama, when they arrived, the troops of the city came out and killed 700 Elamites and 600 Eshnunakeans". They also dropped |

|||

bitumen on the attacker's siege towers and burned them.<ref>Sasson, Jack M., "Siege Mentality: Fighting at the City Gate in the Mari Archives", Marbeh Ḥokmah: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East in Loving Memory of Victor Avigdor Hurowitz, edited by Shamir Yonah, Edward L. Greenstein, Mayer I. Gruber, Peter Machinist and Shalom M. Paul, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 465-478, 2015</ref> After a seige ramp was constructed it was attacked: |

|||

{{blockquote|text="... Citizens made a tunnel in the city. They made two holes in the wall, right and left toward the front of the ramp. At night they entered [that] tunnel, and in the early morning, the troops of the city [came] out and killed half of the troops (of Atamrum). They made them drop the bronze lances and their shields and brought them inside the city"<ref>Vidal, Jordi, "The Siege of Razama, An example of aggressive defence in Old-Babylonian times", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 365-371, 2009</ref><ref>. Heimpel, W., Details of Atamarum's siege of Razama", NABU 102, pp. 89–90, 1996</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

===Location of Razama=== |

|||

In a text found at Mari, Razama it states "500 Turukkeans made a raid below Ekallatum and Aššur and reached Razama" which would place the city south of those cities. [[Ekallatum]] |

|||

is unlocated but is known to be in the vicinity of Assur.<ref>[https://hal.science/hal-04379401v1/file/Ziegler-Otto-2023_BBVO-30_Ekallatum.pdf]Ziegler, Nele, and Adelheid Otto, "Ekallatum, Samsi-Addu’s capital city, localised", Entre les fleuves–III. On the Way in Upper Mesopotamia: Travels, Routes and Environment as Basis for the Reconstruction of Historical Geography 30, pp. 221-252, 2023</ref> In another Mari text a journey of |

|||

ruler Zimri-Lim has him taking the path "... Rassum, Tadum, Ilan-sura, Razama-of-Yussan, and Husla". In a messenger text from Mari a route is recorded of "[The route of the messen]gers [of the Ya]minites [between Ešnunna] and Karana, [he made it known to me] [thus: (from Ešnunna) to Dur]-Sin; [from Dur]-Sin to Arrapha; [from Ar]rapha [to Ka]wa[lhum]; [from K]awalh[um] to Razama of the Yamutbal; from Razama of the Yamutbal to Karana; from Karana to Allahad. To the river bank: this is their route".<ref>Charpin, Dominique, "From Mari to Yakaltum: a route westwards according to the royal archives of Mari", Entre les fleuves–III. On the Way in Upper Mesopotamia: Routes, Travels and Environment as Basis for the Reconstruction of Historical Geography 30, pp. 119-132, 2023</ref> A reconstruction of Old Babylonian period trading routes included one "ASSUR – Sadduatum – Razama sa Bura – Abidiban – Qattara – Razama sa Uhakim – Kaluzanum – Adubazum – Daraqum – Apum ...".<ref>Kolinski, Rafał, "20th century BC in the Khabur Triangle Region and the advent of the Old Assyrian trade with Anatolia", Archaeology of Political Spaces, The Upper Mesopotamian Piedmont in the 2nd Millennium BCE, Berlin: Topoi–Berliner Studien in Antike Welt bd 12, pp. 11-34, 2014</ref><ref>Stratford, Edward, "Tempo of Transport", Volume 1 A Year of Vengeance, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 148-162, 2017</ref> |

|||

[[Tell al-Hawa]] has been suggested as the location. Tell al-Rimah has been proposed based on a tablet found in the palace area, Site C: |

|||

{{blockquote|text="Sarrum-kima-kalima, son of Aniskibal, builder of the palace in Razama, his capital city"<ref>Frayne, Douglas, "Razamā", Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 748-749, 1990</ref><ref>Walker, C. B. F., "A Foundation-Inscription from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 27–30,, 1970</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 110: | Line 143: | ||

*Langlois, A. I., "Archibab 2. Les archives de la princesse Iltani découvertes à Tell al-Rimah (XVIIIe siècle av. J.-C.) et l’histoire du royaume de Karana/Qaṭṭara", Mémoires de NABU 18, Paris: SEPOA, 2017 |

*Langlois, A. I., "Archibab 2. Les archives de la princesse Iltani découvertes à Tell al-Rimah (XVIIIe siècle av. J.-C.) et l’histoire du royaume de Karana/Qaṭṭara", Mémoires de NABU 18, Paris: SEPOA, 2017 |

||

*[[Barbara Parker-Mallowan|Barbara Parker]], "Middle Assyrian Seal Impressions from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 257–268, 1977 |

*[[Barbara Parker-Mallowan|Barbara Parker]], "Middle Assyrian Seal Impressions from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 257–268, 1977 |

||

*Carolyn Postgate, David Oates and Joan Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: The Pottery", Aris & Phillips, 1998, {{ISBN|0-85668-700-6}} |

*[http://hdl.handle.net/11401/88667]Carolyn Postgate, David Oates and Joan Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: The Pottery", Aris & Phillips, 1998, {{ISBN|0-85668-700-6}} |

||

*J. N. Postgate, "A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 31–35, 1970 |

*J. N. Postgate, "A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 31–35, 1970 |

||

*J. N. Postgate, "An Inscribed Jar from Tell Al-Rimah", Iraq 40, pp. 71–5, 1978 |

*J. N. Postgate, "An Inscribed Jar from Tell Al-Rimah", Iraq 40, pp. 71–5, 1978 |

||

Latest revision as of 03:37, 27 November 2024

Qattara/Karana (?) | |

| Location | Nineveh Province, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 36°15′25.51″N 42°26′57.61″E / 36.2570861°N 42.4493361°E |

| Type | tell |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1964–1971 |

| Archaeologists | D. Oates, Theresa Howard Carter |

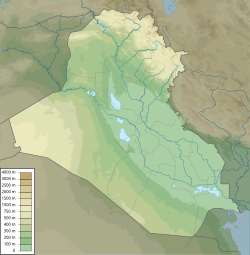

Tell al-Rimah (also Tell ar-Rimah) is an archaeological settlement mound, in Nineveh Province (Iraq) roughly 80 kilometres (50 mi) west of Mosul and ancient Nineveh in the Sinjar region. It lies 15 kilometers south of the site of Tal Afar.

It has been proposed that its ancient name in the 2nd Millennium BC was Karana or Qattara or Razama. Karana and Qattara were very close together and thought to be part of a small kingdom.[1] It has also been suggested that the site's name in the 1st Millennium BC was Zamaḫâ. It is near the circular walled similar archaeological sites of Tell Hadheil, a large Early Dynastic site with Old Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian occupation, and Tell Huweish. Tell Hamira, known earlier as Tell Abu Hamira, is 16 kilometers to the east and has also been suggested as the site of Karana.

Currently, archaeology leans toward Qattara as the ancient name of Tell Al-Rimah.[2]

Archaeology

[edit]The site covers an area roughly 500 meters by 500 meters, surrounded by a polygonal city wall. The interior holds a number of low mounds and a large central mound 30 meters high and 100 meters in diameter.[3]

The region was originally surveyed by Seton Lloyd in 1938.[4] The site of Tell al-Rimah was excavated from 1964 to 1971 by a British School of Archaeology in Iraq team led by David Oates, joined by the Penn Museum and Theresa Howard Carter in the first three years.[5][6][7][8][9][10] A large temple and palace from the early second millennium BC were excavated, as well as a Neo-Assyrian building. Tell al-Rimah also is known for having a third millennium example of brick vaulting.[11] It has been suggested that the city-goddess of Karana was Geshtinanna in Old Babylonian times.[12]

Although on a small portion of the palace was excavated due to it depth, number of Old Babylonian tablets contemporary with Zimri-Lim of Mari and 40 tablets from the time of Shalmaneser I were found as well as other objects. Most of the Older texts were from the time of Karana ruler Aqba-aḫum with a few dating to the tile of earlier ruler Hatnu-rapi. The tablets are mostly administrative documents involving loans of grain or tin.[13][14][15] The tablets also showed a thriving wine industry.[16] A god, Saggar, known from Mari is also attested in the texts.[17]

Old Babylonian period seal was found saying "i-lí-sa-ma-[ás] dumu iq-qa-at utu/iskur ir pí-it-ha-na" ie Ill-Samas, son of Iqqāt-Šamas/Addu, servant of Pithana" which has given rise to the suggestion that this referred to Pithana who was ruler of the Anatolian city of Kuššara though that reading of the rulers name is not certain.[18][19]

Among the finds were over 40 Middle Assyrian period faience rosettes with "transverse perforations on the reverse sides and a knob disc attached to their obverse sides".[20]

History

[edit]Early Bronze

[edit]It appears that the site was occupied in the third millennium BC

Middle Bronze

[edit]It reached its greatest size and prominence during the second millennium BC. The second millennium activity was primarily strong during the Old Babylonian (contemporary with Zimri-Lim of Mari, Hammurabi of Babylon and Ishme-Dagan of Ekallatum who was the son of Shamshi-Adad I) and Mitanni periods. In a letter found at Mari:

"Speak to Yasmah-Addu, thus says Ishme-Dagan your brother. I wrote to you before to say that I had gone to Karana to help Samu-Addu. The ruler of Eshnunna, together with all his troops, his courtiers and his friends, has assembled and is staying in Upe and he kept writing to the ruler of Babylon (Hammurabi) to meet him in Mankisum, but the ruler of Babylon did not agree."[21]

In the Middle Bronze period the site experienced widespread destruction and was abandoned before being re-occupied in the Late Bronze period. In the Mitanni period that followed the Old Babylonian occupation Karana is frequently mentioned in tablets found at the trading city of Nuzi and two Nuzi type tablets were found at Karana. The city was no longer fortified at that time but appears to have been quite prosperous. Another period of abandonment then occurred, followed by re-occupation on a much smaller scale in Neo-Assyrian times.[22]

A notable find was a large archive of letters of Iltani, daughter of Samu-Addu, king of Karana from the Old Babylonian period. The archive covers about a four year period and amounts to about 200 tablets.[23][24] It is known she had at least two sons, one named Yasitna-abum and a sister in Assur.[25] Another sister, Amat-Shamash, who was a priestess in Sippar who once sent her a gift of shrimp.

"The slaves whom my father gave me have grown old; now, I have sent half a mina of silver to the king; allow me my claim and get him to send me slaves who have been captured recently, and who are trustworthy. In recollection of you, I have sent to you five minas of first-rate wool and one container of shrimps"[26]

Her husband was Aqba-aḫum of Qaṭṭara who in a text found at Mari wrote to her saying "The ice (house) of Qaṭṭara should be unsealed, so that the goddess, you, and Belassunu could drink from it as needed. But the ice must remain under guard.".[27] Another Mari text involving Iltani reveals that there was a version of he goddess Istar at Qatara.

"1 goat, offering of Iltani to Išḫara of Aritanaya; 1 goat offering of Iltani to Ištar of Ninet (Nineveh); 1 spring lamb, offering of Iltani to Ištar of Qaṭṭara, when she dedicated (a votive) statue of Yadruk-Addu; 1 lamb, offering of Iltani to Sin [8.x*.Ṣabrum]."[28]

Known rulers of Karana

[edit]- Samu-Addu - father of Iltani and Ashkur-Addu. fled to Eshnunna

- Hatnu-rapi

- Ashkur-Addu - son of Samu-Addu, brother of Iltani, father of Bini-shakim

- Aqba-hammu - husband of Iltani, vassal of Hammurabi

Samu-Addu held power in the last years of Shamshi-Adad of Ekallatum and may have been a vassal. With the death of Shamshi-Adad Mari, under Zimri-Lim expanded in the region and Hatnu-rapi, an ally of Zimri-Lim, took power. Hatnu-rapi was present at the sack of Shubat-Enil, the royal city of Shamshi-Adad. In a letter found at Karana:

"Speak to Hatnu-rapi, thus says Bunu-Ishtar your brother. When you have read this letter, you, Sharriya and the other kings who are on your side get together and muster 4,000 men between you. And I from here shall muster 2,000 men. The former plus the latter, 6,000 good men, let us muster between us, and let us send them quickly to the help of Zimri-Lim; indeed, let us act to save Zimri-Lim. This is not a matter for neglect; let us apply ourselves to this, that we may the sooner send these troops to Zimri-Lim. May my brother not neglect this message of mine!"[29]

Ashkur-Addu then deposed Hatnu-rapi, who fled to Mari. A clay sealing read "Bini-sakin, foremost son of the king, servant of Askur-Addu". A messenger text found at Karana "They have brought in four tablets of the governor of Susa in Elam.... I opened those tablets... but there was no news in them" showed the wide regional interconnections at this time. Aqba-hammu then deposed Ashkur-Addu and became a vassal of Hammurabi.

Iron Age

[edit]

Neo-Assyrian Period

[edit]The site was lightly occupation in the later Iron Age Neo-Assyrian period.

The most notable artifact found was the stele of Adad-nirari III (811 to 783 BC), known as the Tell al-Rimah stela, which may mention an early king of Northern Israel stating "He received the tribute of Ia'asu the Samaritan, of the Tyrian (ruler) and of the Sidonian (ruler)" and contains the first cuneiform mention of Samaria by that name. On the side of the stele was an inscription of Nergal-ereš, who names himself "governor of Raṣappa".[30][31][32] It has been suggested, based on the stele, that Tell al-Rimah has called Zamaḫâ at that time.[33] A larger version of this stele was found at Dūr-Katlimmu.[34]

Razama

[edit]Razama (ra-za-ma-aki) was an ancient Near East city which achieved prominence in the Old Babylonian period and was capital of the land of Yussan/Yassan. It is currently unlocated. A complication is that there were two cities of this name in that period.[35] It is known that at one point the chief archivist at Razama, appointed by Shamshi-Adad I, was a Sîn-iddinam.[36] Their is an unpublished treaty between Mutlya of Apum and Hazip-Tessup of Razamä.[37] The city was briefly controlled by Ishme-Dagan I, ruler of Isin, after attacking it with the assistance of Eshnunna, before it was recaptured by Zimri-Lim.[38]

A text found at Tell Leilan (Subat-Enlil) mentions a Hurrian prince of the Razama, Hazip-Tessup.[39] A tablet found at Me-Turan carried a year name of Silli-Sin, a ruler of Eshnunna who was a contemporary of Hammurabi, "Year Razama was smitten by weapons".[40]

Razama is mentioned in several texts found at the site of Mari. In the 10th regnal year of Mari ruler Zimri-Lim (c. 18th century BC) an army led by Atamrum, king of Allahad and later of Andarig to attack Razama which was ruled by Šarriya/Šarraya (Sharrum-kima-kalima), a vassal of Zimri-Lim. The army consisted of troops from Eshnunna and Elam.[41][42][43] There was a long, and unsuccessful siege of the city. The defenders practiced a strategy of active defense "When troops arrived at Razama, when they arrived, the troops of the city came out and killed 700 Elamites and 600 Eshnunakeans". They also dropped bitumen on the attacker's siege towers and burned them.[44] After a seige ramp was constructed it was attacked:

"... Citizens made a tunnel in the city. They made two holes in the wall, right and left toward the front of the ramp. At night they entered [that] tunnel, and in the early morning, the troops of the city [came] out and killed half of the troops (of Atamrum). They made them drop the bronze lances and their shields and brought them inside the city"[45][46]

Location of Razama

[edit]In a text found at Mari, Razama it states "500 Turukkeans made a raid below Ekallatum and Aššur and reached Razama" which would place the city south of those cities. Ekallatum is unlocated but is known to be in the vicinity of Assur.[47] In another Mari text a journey of ruler Zimri-Lim has him taking the path "... Rassum, Tadum, Ilan-sura, Razama-of-Yussan, and Husla". In a messenger text from Mari a route is recorded of "[The route of the messen]gers [of the Ya]minites [between Ešnunna] and Karana, [he made it known to me] [thus: (from Ešnunna) to Dur]-Sin; [from Dur]-Sin to Arrapha; [from Ar]rapha [to Ka]wa[lhum]; [from K]awalh[um] to Razama of the Yamutbal; from Razama of the Yamutbal to Karana; from Karana to Allahad. To the river bank: this is their route".[48] A reconstruction of Old Babylonian period trading routes included one "ASSUR – Sadduatum – Razama sa Bura – Abidiban – Qattara – Razama sa Uhakim – Kaluzanum – Adubazum – Daraqum – Apum ...".[49][50]

Tell al-Hawa has been suggested as the location. Tell al-Rimah has been proposed based on a tablet found in the palace area, Site C:

"Sarrum-kima-kalima, son of Aniskibal, builder of the palace in Razama, his capital city"[51][52]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Charpin, Dominique, and Jean-Marie Durand, "Le nom antique de Tell Rimāh", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 125–46, 1987

- ^ Nashef, Khaled, "Qaṭṭarā and Karanā", Die Welt Des Orients, vol. 19, 1988, pp. 35–39, 1988

- ^ [1]David Oates, "Excavations at Tell al Rimah A Summary Report", Sumer, vol. 19, no. 1-2, pp. 69-78, 1963

- ^ Seton Lloyd, "Some Ancient Sites in the Sinjar district, Iraq", vol. 5, pp. 123ff, 1938

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1964", Iraq, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 62-68, 1965

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1965", Iraq, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 122-139, 1966

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1966", Iraq, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 70-96, 1967

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1967", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 115-138, 1968

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah, 1968", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 1-26, 1970

- ^ David Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: 1971, Iraq", vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 77-86, 1972

- ^ Barbara Parker, "Cylinder Seals from Tell al Rimah, Iraq", vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 21-38, 1975

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, "Cults and Beliefs", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 112-138, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- ^ H. W. F. Saggs, "The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1965, Iraq", vol. 30, vo. 2, pp. 154-174, 1968

- ^ D. J. Wiseman, "The Tell al Rimah Tablets: 1966, Iraq", vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 175-205, 1968

- ^ Stephanie Page, "The Tablets from Tell Al-Rimah 1967: A Preliminary Report", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 87-97, 1968

- ^ McGovern, Patrick E., "Wine and the Great Empires of the Ancient Near East", Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 167-209, 2019

- ^ Archi, Alfonso, "Studies in the Pantheon of Ebla", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 592-600, 2015

- ^ Lacambre, Denis, and Werner Nahm, "Pithana, an Anatolian Ruler in the Time of Samsuiluna of Babylon: New Data From Tell Rimah (Iraq)", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 109, pp. 17–28, 2015

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Qaṭṭarā / Karanā", Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 737-747, 1990 ISBN 9780802058737

- ^ Puljiz, Ivana, "Faience for the empire: A Study of Standardized Production in the Middle Assyrian State", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 111, no. 1, pp. 100-122, 2021

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, "Rulers and Vassals", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 30-49, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, "The Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 179-207, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- ^ Jesper Eidem, "Some Remarks on the Iltani Archive from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 51, pp. 67–78, 1989

- ^ [2] Langlois, Anne-Isabelle, "“You Had None of a Woman’s Compassion”: Princess Iltani from her Archive Uncovered at Tell al-Rimah (18th Century BCE)", Gender and methodology in the ancient Near East: Approaches from Assyriology and beyond 10, 2018

- ^ Stol, Marten, "The court and the harem before 1500 BC", Women in the Ancient Near East, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 459-511, 2016

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, "Food and Drink", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 78-96, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- ^ Sasson, Jack M., "Religion". From the Mari Archives: An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 235-293, 2015

- ^ Sasson, Jack M., "Culture", From the Mari Archives: An Anthology of Old Babylonian Letters, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 294-342, 2015

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie, "Rulers and Vassals", Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities: With a New Introduction by the Author, Piscataway, NJ, USA: Gorgias Press, pp. 30-49, 2002 ISBN 1-931956-02-2

- ^ Page, Stephanie, "A Stela of Adad-Nirari III and Nergal-Ereš from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 139–53, 1968

- ^ Shea, William H., "Adad-Nirari III and Jehoash of Israel", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 101–13, 1978

- ^ Parpola, Simo, "The Location of Raṣappa", At the Dawn of History: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honour of J. N. Postgate, edited by Yağmur Heffron, Adam Stone and Martin Worthington, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 393-412, 2017

- ^ May, Natalie N., "“The True Image of the God…:” Adoration of the King’s Image, Assyrian Imperial Cult and Territorial Control", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 185-240, 2020

- ^ Radner, Karen, "The Stele of Adad-nērārī III and Nergal-ēreš from Dūr-Katlimmu (Tell Šaiḫ Ḥamad)", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 265-277, 2012

- ^ [3]Goetze, Albrecht, "An Old Babylonian Itinerary", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 7.2, pp. 51-72, 1953

- ^ Koliński, Rafał, "The Fate of Yasmaḫ-Addu, the King of Mari", Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014, edited by Olga Drewnowska and Malgorzata Sandowicz, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 221-236, 2017

- ^ Beckman, Gary, "Hittite Treaties and the Development of the Cuneiform Treaty Tradition", Die deuteronomistischen Geschichtswerke: Redaktions- und religionsgeschichtliche Perspektiven zur "Deuteronomismus"-Diskussion in Tora und Vorderen Propheten, edited by Jan Christian Gertz, Doris Prechel, Konrad Schmid and Markus Witte, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 279-302, 2006

- ^ Beitzel, Barry J., "Išme-Dagan’s Military Actions in the Jezirah: A Geographical Study", Iraq, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 29–42, 1984

- ^ Salvini, Mirjo, "The earliest evidences of the Hurrians before the formation of the reign of Mittanni", Urkesh and the Hurrians Studies in Honor of Lloyd Cotsen, Urkesh/Mozan Studies Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. Malibu: Undena Publications, pp. 99-115, 1998

- ^ Muhamed, Ahmad Kamil, "Old Babylonian Cuneiform Texts from the Hamrin Basin: Tell Hadad", Edubba, vol. 1. London: NABU, 1992

- ^ Charpin, D. – Ziegler, N., "Mari et le Proche-Orient à l’époque amorrite", Essai d’histoire politique (FM V), Paris, 2003

- ^ Heimpel, W., "Letters to the King of Mari", Winona Lake, 2003

- ^ Archi, Alfonso, "Men at War in the Ebla Period: On the Unevenness of the written Documentation", Ebla and Its Archives: Texts, History, and Society, Berlin, München, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 262-291, 2015

- ^ Sasson, Jack M., "Siege Mentality: Fighting at the City Gate in the Mari Archives", Marbeh Ḥokmah: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East in Loving Memory of Victor Avigdor Hurowitz, edited by Shamir Yonah, Edward L. Greenstein, Mayer I. Gruber, Peter Machinist and Shalom M. Paul, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 465-478, 2015

- ^ Vidal, Jordi, "The Siege of Razama, An example of aggressive defence in Old-Babylonian times", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 365-371, 2009

- ^ . Heimpel, W., Details of Atamarum's siege of Razama", NABU 102, pp. 89–90, 1996

- ^ [4]Ziegler, Nele, and Adelheid Otto, "Ekallatum, Samsi-Addu’s capital city, localised", Entre les fleuves–III. On the Way in Upper Mesopotamia: Travels, Routes and Environment as Basis for the Reconstruction of Historical Geography 30, pp. 221-252, 2023

- ^ Charpin, Dominique, "From Mari to Yakaltum: a route westwards according to the royal archives of Mari", Entre les fleuves–III. On the Way in Upper Mesopotamia: Routes, Travels and Environment as Basis for the Reconstruction of Historical Geography 30, pp. 119-132, 2023

- ^ Kolinski, Rafał, "20th century BC in the Khabur Triangle Region and the advent of the Old Assyrian trade with Anatolia", Archaeology of Political Spaces, The Upper Mesopotamian Piedmont in the 2nd Millennium BCE, Berlin: Topoi–Berliner Studien in Antike Welt bd 12, pp. 11-34, 2014

- ^ Stratford, Edward, "Tempo of Transport", Volume 1 A Year of Vengeance, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 148-162, 2017

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Razamā", Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.): Early Periods, Volume 4, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 748-749, 1990

- ^ Walker, C. B. F., "A Foundation-Inscription from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 27–30,, 1970

Further reading

[edit]- Battini, Laura, "La dernière phase du palais de Tell al-Rimah : nouvelle approche", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 115–40, 2001

- Carter, Theresa Howard, "Excavations at Tell al-Rimah, 1964 Preliminary Report", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 178.1, pp. 40-69, 1965

- Carter, Theresa Howard, "Tell al-Rimah: The Campaigns of 1965 and 1966", Archaeology 20.4, pp. 282-289, 1967

- Stephanie Dalley, "Old Babylonian Trade in Textiles at Tell al Rimah, Iraq", vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 155–159, 1977

- Stephanie Dalley, C.B.F Walker and J.D. Hawkins, "The Old Babylonian Tablets from Al-Rimah", British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 1976, ISBN 0-903472-03-1

- Howard-Carter, T., "An Interpretation of the Sculptural Decoration of the Second Millennium Temple at Tell al-Rimah", Iraq 45, pp. 64-72, 1983

- Langlois, A. I., "Archibab 2. Les archives de la princesse Iltani découvertes à Tell al-Rimah (XVIIIe siècle av. J.-C.) et l’histoire du royaume de Karana/Qaṭṭara", Mémoires de NABU 18, Paris: SEPOA, 2017

- Barbara Parker, "Middle Assyrian Seal Impressions from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 257–268, 1977

- [5]Carolyn Postgate, David Oates and Joan Oates, "The Excavations at Tell al Rimah: The Pottery", Aris & Phillips, 1998, ISBN 0-85668-700-6

- J. N. Postgate, "A Neo-Assyrian Tablet from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 31–35, 1970

- J. N. Postgate, "An Inscribed Jar from Tell Al-Rimah", Iraq 40, pp. 71–5, 1978

- Joan Oates, "Late Assyrian Temple Furniture from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 179–184, 1974

- von Saldern, Axel, "Mosaic Glass from Hasanlu, Marlik, and Tell al-Rimah", Journal of Glass Studies, vol. 8, pp. 9–25, 1966

- C. B. F. Walker, "A Foundation-Inscription from Tell al Rimah", Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 27–30, 1970