Expected value of including uncertainty: Difference between revisions

Added short description Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App description add |

|||

| (19 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Concept in decision theory}} |

|||

In [[decision theory]] and quantitative [[policy analysis]], the '''expected value of including |

In [[decision theory]] and quantitative [[policy analysis]], the '''expected value of including uncertainty''' ('''EVIU''') is the expected difference in the value of a decision based on a [[probabilistic analysis]] versus a decision based on an analysis that ignores [[uncertainty]].<ref>{{cite book |author1=Morgan, M. Granger |author2=Henrion, Max |chapter=Chap. 12 |title=Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=1990 |isbn=0-521-36542-2 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite thesis |degree=Ph.D. |title=The value of knowing how little you know: The advantages of a probabilistic treatment of uncertainty in policy analysis |author=Henrion, M. |year=1982 |publisher=Carnegie Mellon University }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) Volume III - Part A: Process for Conducting Probabilistic Risk Assessment |year=2001 |chapter=Appendix D: Advanced Modeling Approaches for Characterizing Variability and Uncertainty |publisher=United States Environmental Protection Agency |url=http://www.epa.gov/oswer/riskassessment/rags3adt/pdf/appendixd.pdf |author=EPA |page=D-20}}</ref> |

||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

Decisions must be made every day in the ubiquitous presence of uncertainty. For most day-to-day decisions, various [[heuristics]] are used to act reasonably in the presence of uncertainty, often with little thought about its presence. However, for larger high-stakes decisions or decisions in highly public situations, decision makers may often benefit from a more systematic treatment of their decision problem, such as through quantitative analysis |

Decisions must be made every day in the ubiquitous presence of uncertainty. For most day-to-day decisions, various [[heuristics]] are used to act reasonably in the presence of uncertainty, often with little thought about its presence. However, for larger high-stakes decisions or decisions in highly public situations, decision makers may often benefit from a more systematic treatment of their decision problem, such as through quantitative analysis or [[decision analysis]]. |

||

When building a quantitative decision model, a model builder identifies various relevant factors, and encodes these as ''input variables''. From these inputs, other quantities, called ''result variables'', can be computed; these provide information for the decision maker. For example, in the example detailed below, |

When building a quantitative decision model, a model builder identifies various relevant factors, and encodes these as ''input variables''. From these inputs, other quantities, called ''result variables'', can be computed; these provide information for the decision maker. For example, in the example detailed below, the decision maker must decide how soon before a flight's schedule departure he must leave for the airport (the decision). One input variable is how long it takes to drive to the airport parking garage. From this and other inputs, the model can compute how likely it is the decision maker will miss the flight and what the net cost (in minutes) will be for various decisions. |

||

To reach a decision, a very common practice is to ignore uncertainty. Decisions are reached through quantitative analysis and model building by simply using a ''best guess'' (single value) for each input variable. Decisions are then made on computed ''point estimates''. In many cases, however, ignoring uncertainty can lead to very poor decisions, with estimations for result variables often misleading the decision maker<ref>{{cite book | |

To reach a decision, a very common practice is to ignore uncertainty. Decisions are reached through quantitative analysis and model building by simply using a ''best guess'' (single value) for each input variable. Decisions are then made on computed ''point estimates''. In many cases, however, ignoring uncertainty can lead to very poor decisions, with estimations for result variables often misleading the decision maker<ref>{{cite book |author1=Danziger, Jeff |author2=Sam L. Savage|title=The Flaw of Averages: Why We Underestimate Risk in the Face of Uncertainty |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-471-38197-6 |url=http://www.flawofaverages.com}}</ref> |

||

An alternative to ignoring uncertainty in |

An alternative to ignoring uncertainty in quantitative decision models is to explicitly encode uncertainty as part of the model. With this approach, a [[probability distribution]] is provided for each input variable, rather than a single best guess. The [[variance]] in that distribution reflects the degree of [[Bayesian probability|subjective uncertainty]] (or lack of knowledge) in the input quantity. The software tools then use methods such as [[Monte Carlo analysis]] to propagate the uncertainty to result variables, so that a decision maker obtains an explicit picture of the impact that uncertainty has on his decisions, and in many cases can make a much better decision as a result. |

||

When comparing the two approaches—ignoring uncertainty versus modeling uncertainty explicitly—the natural question to ask is how much difference it really makes to the quality of the decisions reached. In the 1960s, [[Ronald A. Howard]] proposed<ref>{{cite journal |author=Howard, Ron A. |title=Information value theory |journal=IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics |volume=1 |pages=22–6 |year=1966 }}</ref> one such measure, the [[expected value of perfect information]] (EVPI), a measure of how much it would be worth to learn the "true" values for all uncertain input variables. While providing a highly useful measure of sensitivity to uncertainty, the EVPI does not directly capture the actual improvement in decisions obtained from explicitly representing and reasoning about uncertainty. For this, Max Henrion, in his Ph.D. thesis, introduced the ''expected value of including uncertainty'' (EVIU), the topic of this article. |

When comparing the two approaches—ignoring uncertainty versus modeling uncertainty explicitly—the natural question to ask is how much difference it really makes to the quality of the decisions reached. In the 1960s, [[Ronald A. Howard]] proposed<ref>{{cite journal |author=Howard, Ron A. |title=Information value theory |journal=IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics |volume=1 |pages=22–6 |year=1966 |doi=10.1109/TSSC.1966.300074 }}</ref> one such measure, the [[expected value of perfect information]] (EVPI), a measure of how much it would be worth to learn the "true" values for all uncertain input variables. While providing a highly useful measure of sensitivity to uncertainty, the EVPI does not directly capture the actual improvement in decisions obtained from explicitly representing and reasoning about uncertainty. For this, Max Henrion, in his Ph.D. thesis, introduced the ''expected value of including uncertainty'' (EVIU), the topic of this article. |

||

== Formalization == |

== Formalization == |

||

| Line 25: | Line 26: | ||

U(d,x) & \text{the utility function} |

U(d,x) & \text{the utility function} |

||

\\ |

\\ |

||

f(x) & \text{ |

f(x) & \text{the prior subjective probability distribution (density function) on } x |

||

\end{array} |

\end{array} |

||

</math> |

</math> |

||

When not including uncertainty, |

When not including uncertainty, the optimal decision is found using only <math>E[x]</math>, the expected value of the uncertain quantity. Hence, the decision ''ignoring uncertainty'' is given by: |

||

:<math> |

:<math> |

||

d_{iu} = {\arg\max_{d}} ~ U(d,E[x]) |

d_{iu} = {\arg\max_{d}} ~ U(d,E[x]). |

||

</math> |

</math> |

||

The optimal decision taking uncertainty into account is the standard Bayes decision that maximizes expected utility: |

The optimal decision taking uncertainty into account is the standard Bayes decision that maximizes [[expected utility]]: |

||

:<math> |

:<math> |

||

d^* = {\arg\max_d} {\int U(d,x) f(x) \, dx} |

d^* = {\arg\max_d} {\int U(d,x) f(x) \, dx}. |

||

</math> |

</math> |

||

The EVIU is the difference in expected utility between these two decisions: |

The EVIU is the difference in expected utility between these two decisions: |

||

:<math> |

:<math> |

||

EVIU = \int_{X} \left[ U(d^*,x) - U(d_{iu},x) \right] f(x) \, dx |

EVIU = \int_{X} \left[ U(d^*,x) - U(d_{iu},x) \right] f(x) \, dx. |

||

</math> |

</math> |

||

| Line 50: | Line 51: | ||

== Example == |

== Example == |

||

[[File:EVIU diagram.png|frame|[ |

[[File:EVIU diagram.png|frame|[influence diagram of EVIU model]] |

||

| ⚫ | The diagram at right is an [[influence diagram]] for deciding how early the decision maker should leave home in order to catch a flight at the airport. The single decision, in the green rectangle, is the number of minutes that one will decide to leave prior to the plane's departure time. Four uncertain variables appear on the diagram in cyan ovals: The time required to drive from home to the airport's parking garage (in minutes), time to get from the parking garage to the gate (in minutes), the time before departure that one must be at the gate, and the loss (in minutes) incurred if the flight is missed. Each of these nodes contains a probability distribution, viz: |

||

The plane catching example described here is taken, with permission from [http://lumina.com Lumina Decision Systems], from an example model shipped with the [[Analytica]] visual modeling software. |

|||

| ⚫ | The diagram |

||

Time_to_drive_to_airport := [[Lognormal Distribution|LogNormal]](median:60,gsdev:1.3) |

Time_to_drive_to_airport := [[Lognormal Distribution|LogNormal]](median:60,gsdev:1.3) |

||

| Line 85: | Line 84: | ||

When uncertainty is taken into account, the expected value smooths out (the blue curve), and the optimal action is to leave 140 minutes before the flight. The expected value curve, with a decision at 100 minutes before the flight, shows the expected cost when ignoring uncertainty to be 313.7 minutes, while the expected cost when one leaves 140 minute before the flight is 151 minutes. The difference between these two is the EVIU: |

When uncertainty is taken into account, the expected value smooths out (the blue curve), and the optimal action is to leave 140 minutes before the flight. The expected value curve, with a decision at 100 minutes before the flight, shows the expected cost when ignoring uncertainty to be 313.7 minutes, while the expected cost when one leaves 140 minute before the flight is 151 minutes. The difference between these two is the EVIU: |

||

:<math>EVIU = 313.7 - 151 = 162.7\text{ minutes} |

:<math>EVIU = 313.7 - 151 = 162.7\text{ minutes} </math> |

||

In other words, if uncertainty is explicitly taken into account when the decision is made, an average savings of 162.7 minutes will be realized. |

In other words, if uncertainty is explicitly taken into account when the decision is made, an average savings of 162.7 minutes will be realized. |

||

==Linear-quadratic control== |

|||

In the context of centralized [[linear-quadratic control]], with additive uncertainty in the equation of evolution but no uncertainty about coefficient values in that equation, the optimal solution for the control variables taking into account the uncertainty is the same as the solution ignoring uncertainty. This property, which gives a zero expected value of including uncertainty, is called [[certainty equivalence]]. |

|||

== Relation to expected value of perfect information (EVPI) == |

== Relation to expected value of perfect information (EVPI) == |

||

Both EVIU and [[EVPI]] compare the expected value of the Bayes' decision with another decision made without uncertainty. For EVIU this other decision is made when the uncertainty is ''ignored'', although it is there, while for [[EVPI]] this other decision is made after the uncertainty is ''removed'' by obtaining perfect information about ''x''. |

Both EVIU and [[EVPI]] compare the expected value of the Bayes' decision with another decision made without uncertainty. For EVIU this other decision is made when the uncertainty is ''ignored'', although it is there, while for [[EVPI]] this other decision is made after the uncertainty is ''removed'' by obtaining perfect information about ''x''. |

||

The [[EVPI]] is the expected cost of being uncertain about ''x'', while the EVIU is the additional expected cost of assuming that one is certain. |

The [[EVPI]] is the expected cost of being uncertain about ''x'', while the EVIU is the additional expected cost of assuming that one is certain. |

||

| Line 98: | Line 101: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Expected value of perfect information]] (EVPI) |

|||

*[[Expected value of sample information]] |

*[[Expected value of sample information]] |

||

*[[Bulk Dispatch Lapse]] |

*[[Bulk Dispatch Lapse]] |

||

| Line 106: | Line 108: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Expected Value Of Including Uncertainty}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Expected Value Of Including Uncertainty}} |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Expected utility]] |

||

[[Category:Game theory]] |

[[Category:Game theory]] |

||

Latest revision as of 12:04, 28 November 2024

In decision theory and quantitative policy analysis, the expected value of including uncertainty (EVIU) is the expected difference in the value of a decision based on a probabilistic analysis versus a decision based on an analysis that ignores uncertainty.[1][2][3]

Background

[edit]Decisions must be made every day in the ubiquitous presence of uncertainty. For most day-to-day decisions, various heuristics are used to act reasonably in the presence of uncertainty, often with little thought about its presence. However, for larger high-stakes decisions or decisions in highly public situations, decision makers may often benefit from a more systematic treatment of their decision problem, such as through quantitative analysis or decision analysis.

When building a quantitative decision model, a model builder identifies various relevant factors, and encodes these as input variables. From these inputs, other quantities, called result variables, can be computed; these provide information for the decision maker. For example, in the example detailed below, the decision maker must decide how soon before a flight's schedule departure he must leave for the airport (the decision). One input variable is how long it takes to drive to the airport parking garage. From this and other inputs, the model can compute how likely it is the decision maker will miss the flight and what the net cost (in minutes) will be for various decisions.

To reach a decision, a very common practice is to ignore uncertainty. Decisions are reached through quantitative analysis and model building by simply using a best guess (single value) for each input variable. Decisions are then made on computed point estimates. In many cases, however, ignoring uncertainty can lead to very poor decisions, with estimations for result variables often misleading the decision maker[4]

An alternative to ignoring uncertainty in quantitative decision models is to explicitly encode uncertainty as part of the model. With this approach, a probability distribution is provided for each input variable, rather than a single best guess. The variance in that distribution reflects the degree of subjective uncertainty (or lack of knowledge) in the input quantity. The software tools then use methods such as Monte Carlo analysis to propagate the uncertainty to result variables, so that a decision maker obtains an explicit picture of the impact that uncertainty has on his decisions, and in many cases can make a much better decision as a result.

When comparing the two approaches—ignoring uncertainty versus modeling uncertainty explicitly—the natural question to ask is how much difference it really makes to the quality of the decisions reached. In the 1960s, Ronald A. Howard proposed[5] one such measure, the expected value of perfect information (EVPI), a measure of how much it would be worth to learn the "true" values for all uncertain input variables. While providing a highly useful measure of sensitivity to uncertainty, the EVPI does not directly capture the actual improvement in decisions obtained from explicitly representing and reasoning about uncertainty. For this, Max Henrion, in his Ph.D. thesis, introduced the expected value of including uncertainty (EVIU), the topic of this article.

Formalization

[edit]Let

When not including uncertainty, the optimal decision is found using only , the expected value of the uncertain quantity. Hence, the decision ignoring uncertainty is given by:

The optimal decision taking uncertainty into account is the standard Bayes decision that maximizes expected utility:

The EVIU is the difference in expected utility between these two decisions:

The uncertain quantity x and decision variable d may each be composed of many scalar variables, in which case the spaces X and D are each vector spaces.

Example

[edit]

The diagram at right is an influence diagram for deciding how early the decision maker should leave home in order to catch a flight at the airport. The single decision, in the green rectangle, is the number of minutes that one will decide to leave prior to the plane's departure time. Four uncertain variables appear on the diagram in cyan ovals: The time required to drive from home to the airport's parking garage (in minutes), time to get from the parking garage to the gate (in minutes), the time before departure that one must be at the gate, and the loss (in minutes) incurred if the flight is missed. Each of these nodes contains a probability distribution, viz:

Time_to_drive_to_airport := LogNormal(median:60,gsdev:1.3) Time_from_parking_to_gate := LogNormal(median:10,gsdev:1.3) Gate_time_before_departure := Triangular(min:20,mode:30,max:40) Loss_if_miss_the_plane := LogNormal(median:400,stddev:100)

Each of these distributions is taken to be statistically independent. The probability distribution for the first uncertain variable, Time_to_drive_to_airport, with median 60 and a geometric standard deviation of 1.3, is depicted in this graph:

The model calculates the cost (the red hexagonal variable) as the number of minutes (or minute equivalents) consumed to successfully board the plane. If one arrive too late, one will miss one's plane and incur the large loss (negative utility) of having to wait for the next flight. If one arrives too early, one incurs the cost of a needlessly long wait for the flight.

Models that utilize EVIU may use a utility function, or equivalently they may utilize a loss function, in which case the utility function is just the negative of the loss function. In either case, the EVIU will be positive. The main difference is just that with a loss function, the decision is made by minimizing loss rather than by maximizing utility. The example here uses a loss function, Cost.

The definitions for each of the computed variables is thus:

Time_from_home_to_gate := Time_to_drive_to_airport + Time_from_parking_to_gate + Loss_if_miss_the_plane Value_per_minute_at_home := 1

Cost := Value_per_minute_at_home * Time_I_leave_home +

(If Time_I_leave_home < Time_from_home_to_gate Then Loss_if_miss_the_plane Else 0)

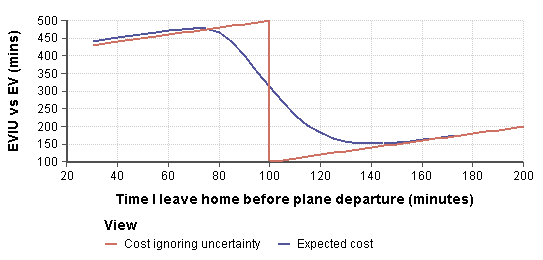

The following graph displays the expected value taking uncertainty into account (the smooth blue curve) to the expected utility ignoring uncertainty, graphed as a function of the decision variable.

When uncertainty is ignored, one acts as though the flight will be made with certainty as long as one leaves at least 100 minutes before the flight, and will miss the flight with certainty if one leaves any later than that. Because one acts as if everything is certain, the optimal action is to leave exactly 100 minutes (or 100 minutes, 1 second) before the flight.

When uncertainty is taken into account, the expected value smooths out (the blue curve), and the optimal action is to leave 140 minutes before the flight. The expected value curve, with a decision at 100 minutes before the flight, shows the expected cost when ignoring uncertainty to be 313.7 minutes, while the expected cost when one leaves 140 minute before the flight is 151 minutes. The difference between these two is the EVIU:

In other words, if uncertainty is explicitly taken into account when the decision is made, an average savings of 162.7 minutes will be realized.

Linear-quadratic control

[edit]In the context of centralized linear-quadratic control, with additive uncertainty in the equation of evolution but no uncertainty about coefficient values in that equation, the optimal solution for the control variables taking into account the uncertainty is the same as the solution ignoring uncertainty. This property, which gives a zero expected value of including uncertainty, is called certainty equivalence.

Relation to expected value of perfect information (EVPI)

[edit]Both EVIU and EVPI compare the expected value of the Bayes' decision with another decision made without uncertainty. For EVIU this other decision is made when the uncertainty is ignored, although it is there, while for EVPI this other decision is made after the uncertainty is removed by obtaining perfect information about x.

The EVPI is the expected cost of being uncertain about x, while the EVIU is the additional expected cost of assuming that one is certain.

The EVIU, like the EVPI, gives expected value in terms of the units of the utility function.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Morgan, M. Granger; Henrion, Max (1990). "Chap. 12". Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-36542-2.

- ^ Henrion, M. (1982). The value of knowing how little you know: The advantages of a probabilistic treatment of uncertainty in policy analysis (Ph.D. thesis). Carnegie Mellon University.

- ^ EPA (2001). "Appendix D: Advanced Modeling Approaches for Characterizing Variability and Uncertainty". Risk Assessment Guidance for Superfund (RAGS) Volume III - Part A: Process for Conducting Probabilistic Risk Assessment (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. p. D-20.

- ^ Danziger, Jeff; Sam L. Savage (2009). The Flaw of Averages: Why We Underestimate Risk in the Face of Uncertainty. New York: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-38197-6.

- ^ Howard, Ron A. (1966). "Information value theory". IEEE Transactions on Systems Science and Cybernetics. 1: 22–6. doi:10.1109/TSSC.1966.300074.

![{\displaystyle E[x]}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/604728821497d9094bd347a8e27040b2ff58c88c)

![{\displaystyle d_{iu}={\arg \max _{d}}~U(d,E[x]).}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/782618c84295c5d3a67a06f17993b69e54573f0a)

![{\displaystyle EVIU=\int _{X}\left[U(d^{*},x)-U(d_{iu},x)\right]f(x)\,dx.}](https://wikimedia.org/enwiki/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/38df70187e4496018e483bfa4a0f98dcc4d41023)