Ahytherium: Difference between revisions

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

m Standardize whitespace in favor of built-in padding - see Template talk:Clade#Whitespace around labels (via WP:JWB) |

||

| (41 intermediate revisions by 22 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Extinct genus of sloths}} |

|||

{{speciesbox |

|||

| name = ''Ahytherium'' |

|||

| fossil_range = |

| fossil_range = [[Late Pleistocene]] ([[Lujanian]]) |

||

| image = |

| image = Ahytherium.png |

||

| |

| image_caption = Skull |

||

| image_caption = |

|||

| genus = Ahytherium |

| genus = Ahytherium |

||

| parent_authority = Cartelle ''et al''., 2008 |

| parent_authority = Cartelle ''et al''., 2008 |

||

| Line 10: | Line 9: | ||

| authority = Cartelle ''et al''., 2008 |

| authority = Cartelle ''et al''., 2008 |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

'''''Ahytherium''''' is an extinct genus of [[megalonychid]] [[sloth]] |

'''''Ahytherium''''' is an extinct genus of [[megalonychid]] [[sloth]] that lived during the Pleistocene of what is now [[Brazil]]. It contains a single species, '''''A. aureum'''''.<ref name= "AhytheriumPB">{{cite web | title = ''Ahytherium'' in the Paleobiology Database | work = [[Fossilworks]] | url = https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=137589 | access-date = 17 December 2021}}</ref><ref name=Cartelle>{{cite journal|last1=Cartelle|first1=C.|last2=De Iuliis|first2=G.|last3=Pujos|first3=F.|year=2008|title=A new species of Megalonychidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the quaternary of Poço Azul (Bahia, Brazil)|journal=Comptes Rendus Palevol|volume=7|issue=6|pages=335–346|doi=10.1016/j.crpv.2008.05.006|bibcode=2008CRPal...7..335C }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The almost-complete skeleton of ''Ahytherium'' alongside remains of another extinct sloth species, ''[[Australonyx]]'', were discovered in Poço Azul, an underwater cave in [[Chapada Diamantina National Park]] in 2005. It was described by Castor Cartelle of [[Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais]]. The bones, which had a length of about {{convert|3|m|ft}} when put together, belong to an animal which presumably was still growing.<ref name=Cartelle/> |

||

== Description == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

This animal is known from well-preserved and nearly complete fossils, including a skeleton of an immature specimen, which in life must have been about three meters long, one meter tall and weighing perhaps half a ton. Like all ground sloths, ''Ahytherium'' was equipped with a robust body and legs equipped with powerful claws. ''Ahytherium'' was similar to other ground sloths such as ''[[Megalonyx]]'' but possessed some features that clearly distinguished it: the head, for example, was extremely short and tall, and possessed dorsally swollen frontal bones. The zygomatic arches were wide, particularly the frontal processes, while the lacrimal bones were narrow, blade-shaped and directed anterolaterally. The dentition included [[Canine tooth|canine teeth]] that were thin, curved and oval in cross-section. The [[humerus]] was equipped with a poorly developed deltopectoral crest, while the [[femur]] possessed a large [[trochanter]] located distally. The shape of the caudal vertebrae indicates that the tail was dorsoventrally flattened. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

== Classification == |

|||

| ⚫ | The almost-complete |

||

''Ahytherium'' is a [[genus (biology)|genus]] of the extinct [[family (biology)|family]] [[Megalonychidae]] within the [[suborder (biology)|suborder]] [[sloth|Folivora]] and the superorder [[Xenarthra]]. The Megalonychidae represent a very diverse group. The closest relatives of the Megalonychidae are the [[Megatheriidae]] and the [[Nothrotheriidae]]. The former include the largest known representatives of the sloths, the latter consist of rather smaller members of the sloths. All three families together are relegated to the superfamily of [[Megatherioidea]]. Within the sloths, the Megalonychidae form a very old lineage, with the oldest known fossils dating to the [[Oligocene]] of [[Patagonia]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Carlini |first1=Alfredo A. |last2=Scillato-Vane |first2=Gustavo J. |date=2004-09-01 |title=The oldest Megalonychidae (Xenarthra: Tardigrada); phylogenetic relationships and an emended diagnosis of the family |url=https://www.schweizerbart.de/papers/njgpa/detail/233/87825/The_oldest_Megalonychidae_Xenarthra_Tardigrada_phylogenetic_relationships_and_an_emended_diagnosis_of_the_family |journal=Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen |volume=233 |issue=3 |language=en |pages=423–443 |doi=10.1127/njgpa/233/2004/423}}</ref> Characteristic features are found in the [[Canine tooth|caniniform]] and [[Incisor|incisiform]] design of the anterior tooth in each case, as well as in the molar-like (molariform) designed posterior teeth. The latter are characterized by two transverse ridges ([[Molar (tooth)|bilophodont]]) on the occlusal surface, which points to a rather leaf-eating diet in the Megalonychidae. Unlike the Megatheriidae and the Nothrotheriidae, the hind foot is [[plantigrade]] in shape and not twisted, thus retaining its original shape.<ref name="McDonald et al. 20083">{{cite book |author1=H. Gregory McDonald |author2=Gerardo de Iuliis |chapter=Fossil history of sloths |pages=39–55 |editor1=Sergio F. Vizcaíno |editor2=W. J. Loughry |title=The Biology of the Xenarthra |publisher=University Press of Florida |year=2008}}</ref> The Megalonychidae were once widespread, with fossil remains found in both [[South America]] and [[Central America]], as well as in [[North America]] as far north as the [[Arctic]].<ref name="McDonald et al. 20083"/> In a classic view based on [[anatomy|skeletal anatomy]] comparisons-based view, the Megalonychidae originally included the sloths of the [[West Indies]] as well as the extant [[two-toed sloth]]s of the genus ''Choloepus'',<ref name="Gaudin 20043">Timothy J. Gaudrin: "Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence". ''Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society'' '''140''', 2004, pp. 255–305.</ref> which are now considered to belong to the superfamily [[Mylodontoidea]].<ref name="Delsuc et al. 20192">Frédéric Delsuc, Melanie Kuch, Gillian C. Gibb, Emil Karpinski, Dirk Hackenberger, Paul Szpak, Jorge G. Martínez, Jim I. Mead, H. Gregory McDonald, Ross D.E. MacPhee, Guillaume Billet, Lionel Hautier und Hendrik N. Poinar: "Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths". ''Current Biology'' '''29''' (12), 2019, pp. 2031–2042, [[doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043]]</ref><ref name="Presslee et al. 20192">Samantha Presslee, Graham J. Slater, François Pujos, Analía M. Forasiepi, Roman Fischer, Kelly Molloy, Meaghan Mackie, Jesper V. Olsen, Alejandro Kramarz, Matías Taglioretti, Fernando Scaglia, Maximiliano Lezcano, José Luis Lanata, John Southon, Robert Feranec, Jonathan Bloch, Adam Hajduk, Fabiana M. Martin, Rodolfo Salas Gismondi, Marcelo Reguero, Christian de Muizon, Alex Greenwood, Brian T. Chait, Kirsty Penkman, Matthew Collins und Ross D. E. MacPhee: "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships". ''Nature Ecology & Evolution'' '''3''', 2019, pp. 1121–1130, [[doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z]]</ref> [[Molecular genetics|Molecular genetic]] However, studies together with [[protein]] analyses failed to establish closer relationships between these individual groups.<ref name="Delsuc et al. 20192" /><ref name="Presslee et al. 20192" /> |

|||

Much of the fossil material of Megalonychidae is fragmentary and largely incomplete. The [[Systematics|systematic]] Relationships of the individual representatives of the group could be worked out therefore so far only insufficiently. However, due to the richness of forms, different lines of development can be traced. One includes largely South American representatives such as ''[[Megistonyx]]'' or ''Ahytherium'' and ''[[Ortotherium]]'', respectively, another consists of the North American forms ''[[Megalonyx]]'' and ''[[Pliometanastes]]'' (here, since based on skeletal features, also Caribbean sloths such as ''[[Megalocnus]]'' or ''[[Neocnus]]'').<ref name="Gaudin 20043" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=McDonald |first1=H. Gregory |last2=Rincón |first2=Ascanio D. |last3=Gaudin |first3=Timothy J. |date=2013 |title=A new genus of megalonychid sloth (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the late Pleistocene (Lujanian) of Sierra de Perija, Zulia State, Venezuela |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=33 |issue=5 |pages=1226–1238 |doi=10.1080/02724634.2013.764883 |bibcode=2013JVPal..33.1226M |s2cid=86159558 |issn=0272-4634}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=McDonald |first1=H. Gregory |last2=Chatters |first2=James C. |last3=Gaudin |first3=Timothy J. |date=2017 |title=A new genus of megalonychid ground sloth (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the late Pleistocene of Quintana Roo, Mexico |url=https://www.academia.edu/33406122 |journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology |volume=37 |issue=3 |pages=e1307206 |doi=10.1080/02724634.2017.1307206 |bibcode=2017JVPal..37E7206M |s2cid=90414512 |issn=0272-4634}}</ref> Currently, however, it is not possible to determine direct ancestors for the North American representatives of Megalonychidae. Consequently, their relationship to the South American forms is rather unknown. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Below is a phylogenetic tree of the Megalonychidae, based on the work of Stinnesbeck and colleagues (2021).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Stinnesbeck |first1=Sarah R. |last2=Stinnesbeck |first2=Wolfgang |last3=Frey |first3=Eberhard |last4=Avilés Olguín |first4=Jerónimo |last5=González |first5=Arturo González |date=2021-10-03 |title=''Xibalbaonyx exinferis'' n. sp. (Megalonychidae), a new Pleistocene ground sloth from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico |journal=Historical Biology |volume=33 |issue=10 |pages=1952–1963 |doi=10.1080/08912963.2020.1754817 |bibcode=2021HBio...33.1952S |s2cid=219425309 |issn=0891-2963}}</ref> |

|||

{{clade|style=white-space:nowrap;font-size:100%;line-height:100% |

|||

|label1=[[Megalonychidae]] |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Eucholoeps]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Pliometanastes]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Pliomorphus]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Megalocnus]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Parocnus]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Neocnus]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Acratocnus]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Choloepus]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Megistonyx]]'' |

|||

|2='''''Ahytherium''''' |

|||

}} |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Nohochichak]]'' |

|||

|2={{clade |

|||

|1=''[[Meizonyx]]'' |

|||

|2=''[[Zacatzontli]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Xibalbaonyx]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Megalonyx]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

|2=''[[Megalonychotherium]]'' |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

==Paleobiology== |

|||

''Ahytherium'' must have been a large, rather slow-moving terrestrial sloth that could defend itself from carnivores with its powerful claws. The flattened shape of the tail suggests that ''Ahytherium'' might have been a good swimmer.<ref name="Cartelle" /> It is suggested to have been a mixed feeder (both browsing and grazing).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dantas |first1=Mário A.T. |last2=Santos |first2=Adaiana M.A. |date=August 2022 |title=Inferring the paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene giant ground sloths from the Brazilian Intertropical Region |journal=Journal of South American Earth Sciences |language=en |volume=117 |pages=103899 |doi=10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103899|bibcode=2022JSAES.11703899D }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* ''[[Thalassocnus]]'' |

* ''[[Thalassocnus]]'' |

||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

*[http://fossilworks.org/bridge.pl?a=taxonInfo&taxon_no=137589 Fossilworks: Ahytherium] |

|||

{{Pilosan genera|M.}} |

|||

{{Taxonbar|from=Q4696453}} |

|||

[[Category:Prehistoric sloths]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric sloths]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Pleistocene xenarthrans]] |

[[Category:Pleistocene xenarthrans]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Monotypic prehistoric placental genera]] |

||

[[Category:Prehistoric mammal genera]] |

|||

[[Category:Holocene extinctions]] |

[[Category:Holocene extinctions]] |

||

[[Category:Pleistocene mammals of South America]] |

|||

[[Category:Lujanian]] |

|||

[[Category:Pleistocene Brazil]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Fossil taxa described in 2008]] |

[[Category:Fossil taxa described in 2008]] |

||

{{paleo-mammal-stub}} |

|||

Latest revision as of 23:11, 30 November 2024

| Ahytherium Temporal range: Late Pleistocene (Lujanian)

| |

|---|---|

| |

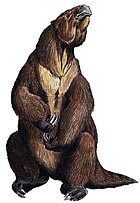

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Megalonychidae |

| Genus: | †Ahytherium Cartelle et al., 2008 |

| Species: | †A. aureum

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Ahytherium aureum Cartelle et al., 2008

| |

Ahytherium is an extinct genus of megalonychid sloth that lived during the Pleistocene of what is now Brazil. It contains a single species, A. aureum.[1][2]

Discovery and taxonomy

[edit]The almost-complete skeleton of Ahytherium alongside remains of another extinct sloth species, Australonyx, were discovered in Poço Azul, an underwater cave in Chapada Diamantina National Park in 2005. It was described by Castor Cartelle of Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais. The bones, which had a length of about 3 metres (9.8 ft) when put together, belong to an animal which presumably was still growing.[2]

Description

[edit]This animal is known from well-preserved and nearly complete fossils, including a skeleton of an immature specimen, which in life must have been about three meters long, one meter tall and weighing perhaps half a ton. Like all ground sloths, Ahytherium was equipped with a robust body and legs equipped with powerful claws. Ahytherium was similar to other ground sloths such as Megalonyx but possessed some features that clearly distinguished it: the head, for example, was extremely short and tall, and possessed dorsally swollen frontal bones. The zygomatic arches were wide, particularly the frontal processes, while the lacrimal bones were narrow, blade-shaped and directed anterolaterally. The dentition included canine teeth that were thin, curved and oval in cross-section. The humerus was equipped with a poorly developed deltopectoral crest, while the femur possessed a large trochanter located distally. The shape of the caudal vertebrae indicates that the tail was dorsoventrally flattened.

Classification

[edit]Ahytherium is a genus of the extinct family Megalonychidae within the suborder Folivora and the superorder Xenarthra. The Megalonychidae represent a very diverse group. The closest relatives of the Megalonychidae are the Megatheriidae and the Nothrotheriidae. The former include the largest known representatives of the sloths, the latter consist of rather smaller members of the sloths. All three families together are relegated to the superfamily of Megatherioidea. Within the sloths, the Megalonychidae form a very old lineage, with the oldest known fossils dating to the Oligocene of Patagonia.[3] Characteristic features are found in the caniniform and incisiform design of the anterior tooth in each case, as well as in the molar-like (molariform) designed posterior teeth. The latter are characterized by two transverse ridges (bilophodont) on the occlusal surface, which points to a rather leaf-eating diet in the Megalonychidae. Unlike the Megatheriidae and the Nothrotheriidae, the hind foot is plantigrade in shape and not twisted, thus retaining its original shape.[4] The Megalonychidae were once widespread, with fossil remains found in both South America and Central America, as well as in North America as far north as the Arctic.[4] In a classic view based on skeletal anatomy comparisons-based view, the Megalonychidae originally included the sloths of the West Indies as well as the extant two-toed sloths of the genus Choloepus,[5] which are now considered to belong to the superfamily Mylodontoidea.[6][7] Molecular genetic However, studies together with protein analyses failed to establish closer relationships between these individual groups.[6][7]

Much of the fossil material of Megalonychidae is fragmentary and largely incomplete. The systematic Relationships of the individual representatives of the group could be worked out therefore so far only insufficiently. However, due to the richness of forms, different lines of development can be traced. One includes largely South American representatives such as Megistonyx or Ahytherium and Ortotherium, respectively, another consists of the North American forms Megalonyx and Pliometanastes (here, since based on skeletal features, also Caribbean sloths such as Megalocnus or Neocnus).[5][8][9] Currently, however, it is not possible to determine direct ancestors for the North American representatives of Megalonychidae. Consequently, their relationship to the South American forms is rather unknown.

Below is a phylogenetic tree of the Megalonychidae, based on the work of Stinnesbeck and colleagues (2021).[10]

Paleobiology

[edit]Ahytherium must have been a large, rather slow-moving terrestrial sloth that could defend itself from carnivores with its powerful claws. The flattened shape of the tail suggests that Ahytherium might have been a good swimmer.[2] It is suggested to have been a mixed feeder (both browsing and grazing).[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ahytherium in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Cartelle, C.; De Iuliis, G.; Pujos, F. (2008). "A new species of Megalonychidae (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the quaternary of Poço Azul (Bahia, Brazil)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 7 (6): 335–346. Bibcode:2008CRPal...7..335C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2008.05.006.

- ^ Carlini, Alfredo A.; Scillato-Vane, Gustavo J. (2004-09-01). "The oldest Megalonychidae (Xenarthra: Tardigrada); phylogenetic relationships and an emended diagnosis of the family". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 233 (3): 423–443. doi:10.1127/njgpa/233/2004/423.

- ^ a b H. Gregory McDonald; Gerardo de Iuliis (2008). "Fossil history of sloths". In Sergio F. Vizcaíno; W. J. Loughry (eds.). The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida. pp. 39–55.

- ^ a b Timothy J. Gaudrin: "Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 140, 2004, pp. 255–305.

- ^ a b Frédéric Delsuc, Melanie Kuch, Gillian C. Gibb, Emil Karpinski, Dirk Hackenberger, Paul Szpak, Jorge G. Martínez, Jim I. Mead, H. Gregory McDonald, Ross D.E. MacPhee, Guillaume Billet, Lionel Hautier und Hendrik N. Poinar: "Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths". Current Biology 29 (12), 2019, pp. 2031–2042, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043

- ^ a b Samantha Presslee, Graham J. Slater, François Pujos, Analía M. Forasiepi, Roman Fischer, Kelly Molloy, Meaghan Mackie, Jesper V. Olsen, Alejandro Kramarz, Matías Taglioretti, Fernando Scaglia, Maximiliano Lezcano, José Luis Lanata, John Southon, Robert Feranec, Jonathan Bloch, Adam Hajduk, Fabiana M. Martin, Rodolfo Salas Gismondi, Marcelo Reguero, Christian de Muizon, Alex Greenwood, Brian T. Chait, Kirsty Penkman, Matthew Collins und Ross D. E. MacPhee: "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships". Nature Ecology & Evolution 3, 2019, pp. 1121–1130, doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z

- ^ McDonald, H. Gregory; Rincón, Ascanio D.; Gaudin, Timothy J. (2013). "A new genus of megalonychid sloth (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the late Pleistocene (Lujanian) of Sierra de Perija, Zulia State, Venezuela". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (5): 1226–1238. Bibcode:2013JVPal..33.1226M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.764883. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 86159558.

- ^ McDonald, H. Gregory; Chatters, James C.; Gaudin, Timothy J. (2017). "A new genus of megalonychid ground sloth (Mammalia, Xenarthra) from the late Pleistocene of Quintana Roo, Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (3): e1307206. Bibcode:2017JVPal..37E7206M. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1307206. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 90414512.

- ^ Stinnesbeck, Sarah R.; Stinnesbeck, Wolfgang; Frey, Eberhard; Avilés Olguín, Jerónimo; González, Arturo González (2021-10-03). "Xibalbaonyx exinferis n. sp. (Megalonychidae), a new Pleistocene ground sloth from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico". Historical Biology. 33 (10): 1952–1963. Bibcode:2021HBio...33.1952S. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1754817. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 219425309.

- ^ Dantas, Mário A.T.; Santos, Adaiana M.A. (August 2022). "Inferring the paleoecology of the Late Pleistocene giant ground sloths from the Brazilian Intertropical Region". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 117: 103899. Bibcode:2022JSAES.11703899D. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2022.103899.