Rufus Thomas: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}} |

||

| (50 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American singer (1917–2001)}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=January 2022}} |

|||

{{Infobox musical artist |

{{Infobox musical artist |

||

|name = Rufus Thomas |

| name = Rufus Thomas |

||

|image = |

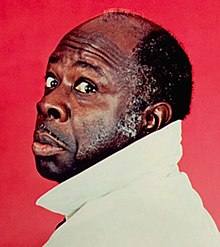

| image = Rufusthomas72.jpg |

||

|caption |

| caption = Thomas in 1972 |

||

|image_size = |

| image_size = |

||

|background = solo_singer |

| background = solo_singer |

||

|birth_name = Rufus C. Thomas, Jr. |

| birth_name = Rufus C. Thomas, Jr. |

||

|alias = Mr. Swing |

| alias = Mr. Swing |

||

|birth_date = {{birth date|1917|3|26}} |

| birth_date = {{birth date|1917|3|26}} |

||

|birth_place =[[Cayce, Mississippi]], U.S. |

| birth_place = [[Cayce, Mississippi]], U.S. |

||

|death_date = {{nowrap|{{death date and age|2001|12|15|1917|3|27}}}} |

| death_date = {{nowrap|{{death date and age|2001|12|15|1917|3|27}}}} |

||

|death_place =[[Memphis, Tennessee]], U.S. |

| death_place = [[Memphis, Tennessee]], U.S. |

||

|instrument = |

| instrument = |

||

|genre = {{flatlist| |

| genre = {{flatlist| |

||

*[[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] |

*[[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] |

||

*[[southern soul]] |

*[[southern soul]] |

||

*[[novelty record|novelty]] |

|||

*[[Blues music|blues]] |

*[[Blues music|blues]] |

||

*[[Dance music|dance]] |

|||

*[[funk]]}} |

*[[funk]]}} |

||

|occupation = [[Singing|Singer]] |

| occupation = {{hlist|[[Singing|Singer]]|[[songwriter]]|[[dancer]]|[[comedian]]|[[television host]]|[[disc jockey]]}} |

||

|years_active = 1936–1998 |

| years_active = 1936–1998 |

||

|label = {{flatlist| |

| label = {{flatlist| |

||

*[[Chess Records|Chess]] |

*[[Chess Records|Chess]] |

||

*[[Sun Records|Sun]] |

*[[Sun Records|Sun]] |

||

*[[Stax Records|Stax]] |

*[[Stax Records|Stax]] |

||

*[[AVI Records|AVI]]}} |

*[[AVI Records|AVI]]}} |

||

|associated_acts = {{flatlist| |

| associated_acts = {{flatlist| |

||

*[[Carla Thomas]] |

*[[Carla Thomas]] |

||

*[[Marvell Thomas]] |

*[[Marvell Thomas]] |

||

*[[Vaneese Thomas]]}} |

*[[Vaneese Thomas]]}} |

||

|website = |

| website = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Rufus C. Thomas, Jr.''' (March 26, 1917 – December 15, 2001)<ref name="bare">{{cite book| |

'''Rufus C. Thomas, Jr.''' (March 26, 1917 – December 15, 2001)<ref name="bare">{{cite book|first1=Bob|last1=Eagle|first2=Eric S.|last2=LeBlanc|year= 2013|title=Blues: A Regional Experience|publisher=Praeger|location=Santa Barbara, California|pages=223–224|isbn= 978-0313344237}}</ref><ref name="AMG">{{cite web|author=Unterberger, Richie|author-link=Richie Unterberger|url=http://www.allmusic.com/artist/rufus-thomas-mn0000303050/biography |title=Rufus Thomas: Biography|publisher=[[AllMusic]].com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/artist/47513-Rufus-Thomas?page=1 |title=Rufus Thomas Discography|publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> was an American [[rhythm and blues|rhythm-and-blues]], [[funk]], [[soul music|soul]] and [[blues]] singer, songwriter, dancer, [[DJ]] and [[entertainer|comic entertainer]] from [[Memphis, Tennessee]]. He recorded for several labels, including [[Chess Records]] and [[Sun Records]] in the 1950s, before becoming established in the 1960s and 1970s at [[Stax Records]]. His [[Dance music|dance records]], including "[[Walking the Dog]]" (1963), "[[Do the Funky Chicken]]" (1969), and "[[(Do the) Push and Pull]]" (1970), were some of his most successful songs. According to the Mississippi Blues Commission, "Rufus Thomas embodied the spirit of Memphis music perhaps more than any other artist, and from the early 1940s until his death . . . occupied many important roles in the local scene."<ref name=msbluestrail/> |

||

He began his career as a [[tap dancer]], [[vaudeville]] performer, and [[master of ceremonies]] in the 1930s. He later worked as a [[disc jockey]] on [[radio station]] [[WDIA]] in Memphis, both before and after his recordings became successful. He remained active into the 1990s and as a performer and recording artist was often billed as "The World's Oldest Teenager". He was the father of the singers [[Carla Thomas]] (with whom [[Rufus and Carla|he recorded duets]]) and [[Vaneese Thomas]] and the keyboard player [[Marvell Thomas]]. |

He began his career as a [[tap dancer]], [[vaudeville]] performer, and [[master of ceremonies]] in the 1930s. He later worked as a [[disc jockey]] on [[radio station]] [[WDIA]] in Memphis, both before and after his recordings became successful. He remained active into the 1990s and as a performer and recording artist was often billed as "The World's Oldest Teenager". He was the father of the singers [[Carla Thomas]] (with whom [[Rufus and Carla|he recorded duets]]) and [[Vaneese Thomas]] and the keyboard player [[Marvell Thomas]]. |

||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

Thomas was born in the rural community of [[Cayce, Mississippi]], the son of a [[sharecropper]]. He moved with his family to |

Thomas was born in the rural community of [[Cayce, Mississippi]], on the outskirts of [[Memphis, Tennessee]], the son of a [[sharecropper]]. He moved with his family to Memphis around 1920.<ref name=msbluestrail>{{cite web|url=http://msbluestrail.org/blues-trail-markers/rufus-thomas|title=Rufus Thomas|website=Mississippi Blues Trail|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> His mother was a "church woman". Thomas made his debut as a performer at the age of six, playing a frog in a school theatrical production. By the age of 10, he was a [[tap dancer]], performing on the streets and in amateur productions at [[Booker T. Washington]] High School, in Memphis.<ref name=msbluestrail/><ref name=nyt>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/19/arts/rufus-thomas-dies-at-84-patriarch-of-memphis-soul.html|author=Pareles, Jon|title=Rufus Thomas Dies at 84; Patriarch of Memphis Soul|work=[[New York Times]]|date=December 19, 2001|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> From the age of 13, he worked with Nat D. Williams, his high-school history teacher, who was also a pioneer black DJ at radio station [[WDIA]] and columnist for black newspapers, as a [[master of ceremonies]] at [[talent show]]s in the Palace Theater on [[Beale Street]].<ref name=nyt/><ref name=memphishall/> After graduating from high school, Thomas attended [[Tennessee State University|Tennessee A&I University]] for one semester, but economic constraints led him to leave to pursue a career as a full-time entertainer. |

||

==Early career== |

==Early career== |

||

Thomas began performing in traveling [[tent show]]s.<ref name=chandler>Chandler, Candice |

Thomas began performing in traveling [[tent show]]s.<ref name=chandler>{{cite web|author=Chandler, Candice|url=http://mswritersandmusicians.com/musicians/rufus-thomas.html|title=Rufus Thomas: A Biography|website=Mississippi Writers and Musicians|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> In 1936 he joined the [[Rabbit Foot Minstrels]], an all-black revue that toured the South, as a tap dancer and [[comedian]], sometimes part of a duo, Rufus and Johnny.<ref name="AMG"/> He married Cornelia Lorene Wilson in 1940, at a service officiated by Rev. [[C. L. Franklin]], the father of [[Aretha Franklin]],<ref name=bowman>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XLdsRwpZ9oYC&pg=PA44|last=Bowman|first=Rob|year=1997|title=Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records|publisher=Music Sales Group|page=9|isbn=9780825672842}}</ref> and the couple settled in Memphis. Thomas worked a [[day job]] in the American Finishing Company textile bleaching plant, which he continued to do for over 20 years.<ref name=msbluestrail/> He also formed a comedy and dancing duo, Rufus and Bones, with Robert "Bones" Couch, and they took over as MCs at the Palace Theater, often presenting amateur hour shows. One early winner was [[B.B. King]], and others discovered by Thomas later in the 1940s included [[Bobby Bland]] and [[Johnny Ace]].<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=nyt/><ref name=spin/> |

||

In the early 1940s, Thomas began writing and performing his own songs. He regarded [[Louis Armstrong]], [[Fats Waller]] and [[Gatemouth Moore]] as musical influences.<ref name=msbluestrail/> He made his professional singing debut at the [[Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks|Elks Club]] on Beale Street, filling in for another singer at the last minute, and during the 1940s became a regular performer in Memphis [[nightclub]]s, such as Currie's Club Tropicana.<ref name=msbluestrail/> As an established performer in Memphis, aged 33 in 1950, Thomas recorded his first [[78 rpm]] [[single (record)|single]], for Jesse Erickson's small Star Talent label in [[Dallas, Texas]]. Thomas said, "I just wanted to make a record. I never thought of getting rich. I just wanted to be known, be a recording artist. . . . [But] the record sold five copies and I bought four of them."<ref>Wilonsky, Robert |

In the early 1940s, Thomas began writing and performing his own songs. He regarded [[Louis Armstrong]], [[Fats Waller]] and [[Gatemouth Moore]] as musical influences.<ref name=msbluestrail/> He made his professional singing debut at the [[Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks|Elks Club]] on Beale Street, filling in for another singer at the last minute, and during the 1940s became a regular performer in Memphis [[nightclub]]s, such as Currie's Club Tropicana.<ref name=msbluestrail/> As an established performer in Memphis, aged 33 in 1950, Thomas recorded his first [[78 rpm]] [[single (record)|single]], for Jesse Erickson's small Star Talent label in [[Dallas, Texas]]. Thomas said, "I just wanted to make a record. I never thought of getting rich. I just wanted to be known, be a recording artist. . . . [But] the record sold five copies and I bought four of them."<ref>{{cite news|author=Wilonsky, Robert|url=http://www.dallasobserver.com/music/good-rockin-last-night-6405791|title=Good Rockin' Last Night|work=[[Dallas Observer]]|date=April 6, 1995|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> The record, "I'll Be a Good Boy" backed with "I'm So Worried", gained a ''[[Billboard (magazine)|Billboard]]'' review, which stated that "Thomas shows first class style on a slow blues".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.706unionavenue.nl/70661165|title="4-Star Records", 706 Union Avenue Sessions|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> He also recorded for the [[Bullet Records|Bullet]] label in [[Nashville, Tennessee]], when he recorded with [[Bobby Plater]]'s Orchestra and was credited as "Mr. Swing"; the recordings were not recognised by researchers as being by Thomas until 1996.<ref name=document>{{cite web|author=Clarke, Dave|url=http://www.document-records.com/fulldetails.asp?ProdID=DOCD-5683|title=Liner notes for Rufus Thomas, Tiger Man: Complete Recordings (1950–1957)|website=Document Records|accessdate=18 July 2015}}</ref> In 1951 he made his first recordings at [[Sam Phillips]]'s [[Sun Studio]], for the [[Chess Records|Chess]] label, but they were not commercially successful.<ref name=document/><ref name=soulfulkindamusic/> |

||

He began working as a DJ at radio station WDIA in 1951, and hosted an afternoon R&B show called ''Hoot and Holler''. WDIA, featuring an African-American format, was known as "the mother station of the Negroes" and became an important source of [[blues]] and R&B music for a generation, its audience consisting of white as well as black listeners. Thomas used to introduce his shows saying, "I'm young, I'm loose, I'm full of juice, I got the goose so what's the use. We're feeling gay though we ain't got a dollar, Rufus is here, so hoot and holler."<ref name="interview part one"/> |

He began working as a DJ at radio station WDIA in 1951, and hosted an afternoon R&B show called ''Hoot and Holler''. WDIA, featuring an African-American format, was known as "the mother station of the Negroes" and became an important source of [[blues]] and R&B music for a generation, its audience consisting of white as well as black listeners. Thomas used to introduce his shows saying, "I'm young, I'm loose, I'm full of juice, I got the goose so what's the use. We're feeling gay though we ain't got a dollar, Rufus is here, so hoot and holler."<ref name="interview part one"/> He also used to lead tours of white teenagers on "midnight rambles" around Beale Street.<ref name="interview part one">{{cite web|url=http://openvault.wgbh.org/catalog/cdeeec-interview-with-rufus-thomas-part-1-of-4|title=WGBH, Interview with Rufus Thomas, part 1|accessdate=19 July 2015}}</ref> Thomas claimed to be the first black DJ to play Elvis Presley records, which he did until the station program director made him stop due to segregation. Shortly thereafter, Thomas performed on stage with Elvis to an all-black audience and the audience stormed through to get to him. After that, the program director allowed Elvis songs to be played on WDIA.<ref name="interview part one" /> |

||

His celebrity in the South was such that in 1953, at Sam Phillips's suggestion, he recorded "Bear Cat" for [[Sun Records]], an "[[answer record]]" to [[Big Mama Thornton]]'s R&B hit "[[Hound Dog (song)|Hound Dog]]".<ref name="AMG"/> The record became |

His celebrity in the South was such that in 1953, at Sam Phillips's suggestion, he recorded "Bear Cat" for [[Sun Records]], an "[[answer record]]" to [[Big Mama Thornton]]'s R&B hit "[[Hound Dog (song)|Hound Dog]]".<ref name="AMG"/> The record became the label's first national chart hit, reaching number 3 on the ''Billboard'' [[R&B chart]]. However, a copyright-infringement suit brought by [[Don Robey]], the original publisher of "Hound Dog", nearly bankrupted the record label.<ref name="AMG"/> After only one recording there, Thomas was one of the African-American artists released by Phillips,<ref name="AMG"/> as he oriented his label more toward white audiences and signed [[Elvis Presley]], who later recorded Thomas's song "[[Tiger Man (song)|Tiger Man]]".<ref name=memphishall/><ref>{{cite book|title=The Late, Great Johnny Ace and the Transition from R & B to Rock 'n' Roll|first=James M.|last=Salem|publisher=University of Illinois Press|year=2001| |

||

isbn=0-252-06969-2}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://whatconsumesme.com/2009/posts-ive-written/sam-phillips-and-the-remix/|title=Sam Phillips and the Remix|publisher=Whatconsumesme.com|access-date=2012-12-04|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120313032744/http://whatconsumesme.com/2009/posts-ive-written/sam-phillips-and-the-remix/|archive-date=2012-03-13}}</ref> |

isbn=0-252-06969-2}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://whatconsumesme.com/2009/posts-ive-written/sam-phillips-and-the-remix/|title=Sam Phillips and the Remix|publisher=Whatconsumesme.com|access-date=2012-12-04|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120313032744/http://whatconsumesme.com/2009/posts-ive-written/sam-phillips-and-the-remix/|archive-date=2012-03-13}}</ref> Thomas did not record again until 1956, when he made a single, "I'm Steady Holdin' On", for the [[Bihari brothers]]' [[Meteor Records|Meteor]] label; musicians on the record included [[Lewie Steinberg]], later a founding member of [[Booker T and the MGs]].<ref name=document/> |

||

==Stax Records== |

==Stax Records== |

||

In 1960 he made his first recordings with his 17-year-old daughter Carla, for the [[Satellite Records|Satellite]] label in Memphis, which changed its name to Stax the following year. The song, "Cause I Love You", featuring a rhythm borrowed from [[Jesse Hill]]'s "Ooh Poo Pa Doo", was a regional hit; the musicians included Thomas' son Marvell on keyboards, Steinberg, and the 16-year-old [[Booker T. Jones]].<ref name=memphishall/><ref name=bowman/> |

In 1960 he made his first recordings with his 17-year-old daughter Carla, for the [[Satellite Records|Satellite]] label in Memphis, which changed its name to Stax the following year. The song, "Cause I Love You", featuring a rhythm borrowed from [[Jesse Hill]]'s "Ooh Poo Pa Doo", was a regional hit; the musicians included Thomas' son Marvell on keyboards, Steinberg, and the 16-year-old [[Booker T. Jones]].<ref name=memphishall/><ref name=bowman/> The record's success led to Stax gaining production and distribution deal with the much larger [[Atlantic Records]].<ref name=msbluestrail/> |

||

Rufus Thomas continued to record for the label after Carla's record "[[Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)]]" reached the national [[Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs|R&B chart]] in 1961. He had his own hit with "The Dog", a song he had originally improvised in performance based on a [[Willie Mitchell (musician)|Willie Mitchell]] bass line, complete with imitations of a barking dog. The 1963 follow-up, "Walking the Dog", engineered by [[Tom Dowd]] of Atlantic, became one of his most successful records, reaching #10 on the ''Billboard'' pop chart.<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=nyt/><ref> |

Rufus Thomas continued to record for the label after Carla's record "[[Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)]]" reached the national [[Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs|R&B chart]] in 1961. He had his own hit with "The Dog", a song he had originally improvised in performance based on a [[Willie Mitchell (musician)|Willie Mitchell]] bass line, complete with imitations of a barking dog. The 1963 follow-up, "Walking the Dog", engineered by [[Tom Dowd]] of Atlantic, became one of his most successful records, reaching #10 on the ''Billboard'' pop chart.<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=nyt/><ref>{{cite book|first=Rob|last=Bowman|title= Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records|publisher=Omnibus Press|year=2011|pages=43–44|isbn=9780857124999}}</ref><ref name="whitburnr&b"/> He became the first, and still the only, father to debut in the Top 10 after his daughter had first appeared there. The song was recorded in early 1964 by [[the Rolling Stones]] on their [[The Rolling Stones (album)|debut album]], and was a minor UK chart hit for [[Merseybeat]] group [[the Dennisons]] later that year.<ref>{{cite book|author=Betts, Graham|year=2004|title=Complete UK Hit Singles 1952–2004|edition=1st|location=London|publisher=Collins|page=211|isbn=0-00-717931-6}}</ref> |

||

As well as recording and appearing on radio and in clubs, Thomas continued to work as a boiler operator in the textile plant, where he claimed the noises sometimes suggested musical rhythms and lyrics to him, before he finally gave up the job in 1963,<ref name=msbluestrail/> to focus on his role as a singer and entertainer. He recorded a series of novelty dance tracks, including |

As well as recording and appearing on radio and in clubs, Thomas continued to work as a boiler operator in the textile plant, where he claimed the noises sometimes suggested musical rhythms and lyrics to him, before he finally gave up the job in 1963,<ref name=msbluestrail/> to focus on his role as a singer and entertainer. He recorded a series of novelty dance tracks, including "Can Your Monkey Do the Dog'" and '"Somebody Stole My Dog" for Stax, where he was often backed by Booker T. & the MGs or [[the Bar-Kays]]. He also became a mentor to younger Stax stars,<ref name="AMG"/> giving advice on stage moves to performers like [[Otis Redding]], who partnered daughter Carla on record.<ref name=nyt/> |

||

After "Jump Back" in 1964, the hits dried up for several years, as Stax gave more attention to younger artists and musicians. However, in 1970 he had another big hit with "[[Do the Funky Chicken]]", which reached #5 on the R&B chart, #28 on the pop chart, and #18 in Britain where it was his only chart hit.<ref name="betts"/> |

After "Jump Back" in 1964, the hits dried up for several years, as Stax gave more attention to younger artists and musicians. However, in 1970 he had another big hit with "[[Do the Funky Chicken]]", which reached #5 on the R&B chart, #28 on the pop chart, and #18 in Britain where it was his only chart hit.<ref name="betts"/> Thomas improvised the song while performing with Willie Mitchell's band at a club in [[Covington, Tennessee]], including a spoken word section that he regularly used as a ''[[shtick]]'' as a radio DJ: "Oh I feel so unnecessary - this is the kind of stuff that makes you feel like you wanna do something nasty, like waste some chicken gravy on your white shirt right down front." The recording was produced by [[Al Bell]] and Tom Nixon, and used the Bar-Kays, featuring guitarist Michael Toles. Thomas continued to work with Bell and Nixon as producers, and later in 1970 had his only number 1 R&B hit [and his second-highest pop charting record] with another dance song, "Do the Push and Pull".<ref name="whitburnr&b"/><ref>{{cite book|first=Rob|last=Bowman|title= Soulsville, U.S.A.: The Story of Stax Records|publisher=Omnibus Press|year=2011|pages=195–196|isbn=9780857124999}}</ref> A further dance-oriented release in 1971, "The Breakdown", climbed to number 2 R&B and number 31 Pop. In 1972, he featured in the [[Wattstax]] concert, and he had several further, less successful, hits before Stax collapsed in 1976.<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=nyt/> |

||

==Later career== |

==Later career== |

||

| ⚫ | Thomas continued to record and toured internationally, billing himself as "The World's Oldest Teenager" and describing himself as "the funkiest man alive".<ref name=spin/> He "drew upon his vaudeville background to put [his songs] over on stage with fancy footwork that displayed remarkable agility for a man well into his fifties",<ref name="AMG"/> and usually performed "while clothed in a wardrobe of [[hot pants]], boots and capes, all in wild colors."<ref name=msbluestrail/> |

||

[[File:Rufusthomaspoison.jpg|left|thumb|200px|Thomas' 1988 album for Alligator Records, ''That Woman Is Poison!'']] |

|||

| ⚫ | Thomas continued to record and toured internationally, billing himself as "The World's Oldest Teenager" and describing himself as "the funkiest man alive".<ref name=spin/> |

||

He continued as a DJ at WDIA until 1974, and worked for a period at [[WLOK]] before returning to WDIA in the mid |

He continued as a DJ at WDIA until 1974, and worked for a period at [[WLOK]] before returning to WDIA in the mid-1980s to co-host a blues show.<ref name=msbluestrail/> He appeared regularly on television and recorded albums for various labels.<ref name=nyt/> Thomas performed regularly at the [[Porretta Soul Festival]] in [[Italy]]; the outdoor amphitheater in which he performed was later renamed Rufus Thomas Park.<ref name=chandler/> |

||

He played an important part in the Stax reunion of 1988, and appeared in [[Jim Jarmusch]]'s 1989 film ''[[Mystery Train (film)|Mystery Train]]'', [[Robert Altman]]'s 1999 film ''[[Cookie's Fortune]]'', and [[D. A. Pennebaker]]’s documentary ''Only the Strong Survive''.<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=msbluestrail/> |

He played an important part in the Stax reunion of 1988, and appeared in [[Jim Jarmusch]]'s 1989 film ''[[Mystery Train (film)|Mystery Train]]'', [[Robert Altman]]'s 1999 film ''[[Cookie's Fortune]]'', and [[D. A. Pennebaker]]’s documentary ''Only the Strong Survive''.<ref name="AMG"/><ref name=msbluestrail/> Thomas released an album of straight-ahead blues, ''[[That Woman Is Poison!]]'', with [[Alligator Records]] in 1988, featuring saxophonist [[Noble "Thin Man" Watts]].<ref name=spin>{{cite magazine|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bT9Dc3mzdZ8C&dq=%22funky+chicken%22+rufus&pg=PA15|first=Robert|last=Gordon|title=Funky Chicken|magazine=[[Spin (magazine)|Spin]]|date=March 1989|page=15|accessdate=17 July 2015|issn=0886-3032|publisher=SPIN Media LLC|volume=4|issue=12}}</ref> In 1996, he and [[William Bell (singer)|William Bell]] headlined at the Olympics in [[Atlanta, Georgia]]. In 1997, he released an album, ''Rufus Live!'', on Ecko Records. In 1998, he hosted two [[New Year's Eve]] shows on Beale Street.<ref name=chandler/> |

||

In 1997, to commemorate his 80th birthday, the [[Memphis, Tennessee|City of Memphis]] renamed a road off Beale Street, close to the old Palace Theater, as Rufus Thomas Boulevard.<ref name=nyt/> He received a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1992, and a lifetime achievement award from [[ASCAP]] in 1997.<ref name=nyt/> |

In 1997, to commemorate his 80th birthday, the [[Memphis, Tennessee|City of Memphis]] renamed a road off Beale Street, close to the old Palace Theater, as Rufus Thomas Boulevard.<ref name=nyt/> He received a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1992, and a lifetime achievement award from [[ASCAP]] in 1997.<ref name=nyt/> He was inducted into the [[Blues Hall of Fame]] in 2001.<ref name="AMG"/> |

||

==Death and legacy== |

==Death and legacy== |

||

[[File:Rufus Thomas Grave New Park Cem Memphis TN 3.jpg|thumb|Rufus Thomas' grave, at the New Park Cemetery in [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]]]] |

[[File:Rufus Thomas Grave New Park Cem Memphis TN 3.jpg|thumb|Rufus Thomas' grave, at the New Park Cemetery in [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]]]] |

||

He died of [[heart failure]] in 2001, at the age of 84, at St. Francis Hospital in Memphis.<ref name="AMG"/> |

He died of [[heart failure]] in 2001, at the age of 84, at St. Francis Hospital in Memphis.<ref name="AMG"/> He is buried next to his wife Lorene, who died in 2000, at the New Park Cemetery in Memphis. |

||

Writer [[Peter Guralnick]] said of him:<ref name=memphishall> |

Writer [[Peter Guralnick]] said of him:<ref name=memphishall>{{cite web|url=http://memphismusichalloffame.com/inductee/rufusthomas/|first=Peter|last=Guralnick|title=Rufus Thomas|website=Memphis Music Hall of Fame|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref><blockquote>His music... brought a great deal of joy to the world, but his personality brought even more, conveying a message of grit, determination, indomitability, above all a bottomless appreciation for the human comedy that left little room for the drab or the dreary in his presence.</blockquote> |

||

Thomas was honored with a marker on the [[Mississippi Blues Trail]] in Byhalia.<ref name="msbluestrail" /> |

Thomas was honored with a marker on the [[Mississippi Blues Trail]] in Byhalia.<ref name="msbluestrail" /> |

||

On June 25, 2019, ''[[The New York Times Magazine]]'' listed Rufus Thomas among hundreds of artists whose material was reportedly destroyed in the [[2008 Universal fire]].<ref name="Rosen2">{{cite web |last1=Rosen |first1=Jody |title=Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/25/magazine/universal-music-fire-bands-list-umg.html |website=The New York Times |access-date=June 28, 2019 |date=June 25, 2019}}</ref> |

|||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

[[Bobby Brown]] portrays Thomas in the [[Black Entertainment Television|BET]] television series ''[[American Soul]]''. |

[[Bobby Brown]] portrays Thomas in the [[Black Entertainment Television|BET]] television series ''[[American Soul]]''. |

||

A character named Rufus in “[[Kill Bill: Volume 2]]” played with Rufus Thomas.{{cn|date=December 2024}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

His name is referenced on the [[Beastie Boys]] album ''[[Check Your Head]]''. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

===Albums=== |

===Albums=== |

||

{| class="wikitable |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2"| Year |

|||

! rowspan="2"| Title |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

! colspan="3"| Peak chart positions |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! style="width:40px;"| <small>[[Billboard 200|US<br>200]]</small><br><ref name="Awards">{{cite web|title=Rufus Thomas - Awards |url=http://www.allmusic.com/artist/rufus-thomas-mn0000303050/awards|website=AllMusic|access-date=28 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130802131911/http://www.allmusic.com/artist/rufus-thomas-mn0000303050/awards|archive-date=August 2, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

! Year |

|||

! style="width:40px;"| <small>[[Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums|US<br>R&B]]</small><br><ref name="Awards"/> |

|||

! Title |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1963 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1963 |

||

| ''[[Walking the Dog (album)|Walking the Dog]]'' |

| ''[[Walking the Dog (album)|Walking the Dog]]'' |

||

| Stax 704<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Walking-The-Dog/release/2147617 |

| Stax 704<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Walking-The-Dog/release/2147617|title=Rufus Thomas – Walking the Dog |date=November 1963 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| 138 |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1970 |

| style="text-align:center;" rowspan="2"|1970 |

||

| ''Do the Funky Chicken'' |

| ''Do the Funky Chicken'' |

||

| Stax STS-2028<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Do-The-Funky-Chicken/release/3872363 |

| Stax STS-2028<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Do-The-Funky-Chicken/release/3872363|title=Rufus Thomas – Do the Funky Chicken |date=September 10, 1970 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| 32 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ''Rufus Thomas Live: Doing the Push & Pull at P.J.'s'' |

| ''Rufus Thomas Live: Doing the Push & Pull at P.J.'s'' |

||

| Stax STS-2039<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Rufus-Thomas-Live-Doing-The-Push-Pull-At-PJs/release/1313278 |

| Stax STS-2039<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Rufus-Thomas-Live-Doing-The-Push-Pull-At-PJs/release/1313278|title=Rufus Thomas – Rufus Thomas Live Doing the Push & Pull at P.J.'s|date=September 10, 1971 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| 147 |

|||

| align=center| 19 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1972 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1972 |

||

| ''Did You Heard Me?'' |

| ''Did You Heard Me?'' |

||

| Stax STS-3004<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Did-You-Heard-Me/release/887891 |

| Stax STS-3004<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Did-You-Heard-Me/release/887891|title=Rufus Thomas – Did You Heard Me? |date=September 10, 1972 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1973 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1973 |

||

| ''Crown Prince of Dance'' |

| ''Crown Prince of Dance'' |

||

| Stax STS-3008<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Crown-Prince-Of-Dance/release/1072929 |

| Stax STS-3008<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-Crown-Prince-Of-Dance/release/1072929|title=Rufus Thomas – Crown Prince of Dance |date=September 10, 1973 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| 42 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1977 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1977 |

||

| ''If There Were No More Music'' |

| ''If There Were No More Music'' |

||

| AVI 6015<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-If-There-Were-No-Music/release/2587456 |

| AVI 6015<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-If-There-Were-No-Music/release/2587456|title=Rufus Thomas – If There Were No Music |date=September 10, 1977 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1978 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1978 |

||

| ''I Ain't Gettin' Older, I'm Gettin' Better'' |

| ''I Ain't Gettin' Older, I'm Gettin' Better'' |

||

| AVI 6046<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-I-Aint-Gettin-Older-Im-Gettin-Better/release/5037766 |title=Rufus Thomas – I Ain't Gettin' Older, I'm Gettin' Better |publisher=Discogs.com |

| AVI 6046<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-I-Aint-Gettin-Older-Im-Gettin-Better/release/5037766 |title=Rufus Thomas – I Ain't Gettin' Older, I'm Gettin' Better|date=September 10, 1978 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1988 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1988 |

||

| ''That Woman Is Poison!'' |

| ''[[That Woman Is Poison!]]'' |

||

| Alligator AL 4769<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-That-Woman-Is-Poison/release/2366484 |

| Alligator AL 4769<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Rufus-Thomas-That-Woman-Is-Poison/release/2366484|title=Rufus Thomas – That Woman Is Poison!|date=September 10, 1988 |publisher=Discogs.com|access-date=2015-07-16}}</ref> |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1996 |

| style="text-align:center;" rowspan="2"|1996 |

||

| ''Blues Thang!'' |

| ''Blues Thang!'' |

||

| Sequel/Castle SEQ 1054 |

| Sequel/Castle SEQ 1054 |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1996 |

|||

| ''The Best of Rufus Thomas: Do the Funky Somethin' '' (compilation) |

| ''The Best of Rufus Thomas: Do the Funky Somethin' '' (compilation) |

||

| Rhino R2 72410 |

| Rhino R2 72410 |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|1997 |

| style="text-align:center;"|1997 |

||

| ''Rufus Live!'' [rec. 1996 at Southern Crossroads Festival in Atlanta, GA] |

| ''Rufus Live!'' [rec. 1996 at Southern Crossroads Festival in Atlanta, GA] |

||

| Ecko ECD 1013 |

| Ecko ECD 1013 |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align:center;"|2000 |

| style="text-align:center;"|2000 |

||

| ''Swing Out with Rufus Thomas'' |

| ''Swing Out with Rufus Thomas'' |

||

| High Stacks HS 9982 |

| High Stacks HS 9982 |

||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ''Just Because I'm Leavin''' (posthumous) |

|||

| Segue Records SRRT05 |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

| align=center| — |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan="6" style="text-align:center; font-size:9pt;"| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Source:<ref name=wangdangdula/> |

Source:<ref name=wangdangdula/> |

||

===Singles=== |

===Singles=== |

||

{| class="wikitable |

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! rowspan="2"| Year |

! rowspan="2"| Year |

||

! rowspan="2"| A-side |

! rowspan="2"| A-side |

||

! rowspan="2"| |

! rowspan="2"| B-side |

||

! rowspan="2"| Catalogue no. |

! rowspan="2"| Catalogue no. |

||

! colspan="3"| Chart positions |

! colspan="3"| Chart positions |

||

|- style="font-size:smaller;" |

|- style="font-size:smaller;" |

||

! width="40"| [[Billboard Hot 100|US Pop]]<ref>{{cite book|first=Joel|last=Whitburn|year=2003|title=Top Pop Singles 1955–2002|publisher=Record Research|location=Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin|isbn=0-89820-155-1|page=[https://archive.org/details/joelwhitburnstop00whitbur/page/709 709]|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/joelwhitburnstop00whitbur/page/709}}</ref> |

! width="40"| [[Billboard Hot 100|US Pop]]<br><ref>{{cite book|first=Joel|last=Whitburn|year=2003|title=Top Pop Singles 1955–2002|publisher=Record Research|location=Menomonee Falls, Wisconsin|isbn=0-89820-155-1|page=[https://archive.org/details/joelwhitburnstop00whitbur/page/709 709]|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/joelwhitburnstop00whitbur/page/709}}</ref> |

||

! width="40"| [[Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs|US<br>R&B]]<ref name="whitburnr&b">{{cite book |

! width="40"| [[Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs|US<br>R&B]]<br><ref name="whitburnr&b">{{cite book|title=Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles: 1942–1995|last=Whitburn|first=Joel |author-link=Joel Whitburn|year=1996|publisher=Record Research|page=442}}</ref> |

||

! width="40"| [[UK Singles Chart|UK]]<ref name="betts">{{cite book| |

! width="40"| [[UK Singles Chart|UK]]<br><ref name="betts">{{cite book|first=Graham|last=Betts|year=2004|title=Complete UK Hit Singles 1952–2004|publisher= Collins|location= London|isbn=0-00-717931-6|page=782}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1950 |

| rowspan="2"| 1950 |

||

| Line 156: | Line 192: | ||

| align="left"| "I'm So Worried" |

| align="left"| "I'm So Worried" |

||

| align="left"| Star Talent 807 |

| align="left"| Star Talent 807 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Gonna Bring My Baby Back" <br>(<small>as '''Mr. Swing with [[Bobby Plater]]'s Orchestra'''</small>)<ref>[http://www.706unionavenue.nl/70661166 Bullet Records, ''706 Union Avenue Sessions'']. Retrieved 17 July 2015</ref> |

| align="left"| "Gonna Bring My Baby Back" <br>(<small>as '''Mr. Swing with [[Bobby Plater]]'s Orchestra'''</small>)<ref>[http://www.706unionavenue.nl/70661166 Bullet Records, ''706 Union Avenue Sessions'']. Retrieved 17 July 2015</ref> |

||

| align="left"| "Beer Bottle Boogie" <br>(<small>as '''Mr. Swing with Bobby Plater's Orchestra'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "Beer Bottle Boogie" <br>(<small>as '''Mr. Swing with Bobby Plater's Orchestra'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| Bullet 327 |

| align="left"| Bullet 327 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1951 |

| rowspan="1"| 1951 |

||

| Line 171: | Line 207: | ||

| align="left"| "Why Did You Dee Gee" |

| align="left"| "Why Did You Dee Gee" |

||

| align="left"| Chess 1466 |

| align="left"| Chess 1466 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1952 |

| rowspan="2"| 1952 |

||

| Line 179: | Line 215: | ||

| align="left"| "Crazy 'Bout You, Baby" |

| align="left"| "Crazy 'Bout You, Baby" |

||

| align="left"| Chess 1492 |

| align="left"| Chess 1492 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Juanita" |

| align="left"| "Juanita" |

||

| align="left"| "Decorate the Counter" |

| align="left"| "Decorate the Counter" |

||

| align="left"| Chess 1517 |

| align="left"| Chess 1517 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1953 |

| rowspan="2"| 1953 |

||

| Line 194: | Line 230: | ||

| align="left"| "Walking in the Rain" |

| align="left"| "Walking in the Rain" |

||

| align="left"| Sun 181 |

| align="left"| Sun 181 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 3 |

| 3 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Tiger Man (King of the Jungle)" |

| align="left"| "[[Tiger Man (song)|Tiger Man (King of the Jungle)]]" |

||

| align="left"| "Save Your Money" |

| align="left"| "Save Your Money" |

||

| align="left"| Sun 188 |

| align="left"| Sun 188 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1956 |

| rowspan="1"| 1956 |

||

| Line 209: | Line 245: | ||

| align="left"| "The Easy Livin' Plan" |

| align="left"| "The Easy Livin' Plan" |

||

| align="left"| Meteor 5039 |

| align="left"| Meteor 5039 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1960 |

| rowspan="1"| 1960 |

||

| Line 217: | Line 253: | ||

| align="left"| "Deep Down Inside"<br>(<small>as '''Carla and Rufus'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "Deep Down Inside"<br>(<small>as '''Carla and Rufus'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| Satellite 102; <br/>Atco 6177 |

| align="left"| Satellite 102; <br/>Atco 6177 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1961 |

| rowspan="1"| 1961 |

||

| Line 225: | Line 261: | ||

| align="left"| "Yeah, Yea-Ah"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus and Friend'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "Yeah, Yea-Ah"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus and Friend'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| Atco 6199 |

| align="left"| Atco 6199 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1962 |

| rowspan="1"| 1962 |

||

| Line 233: | Line 269: | ||

| align="left"| "It's Aw'right" |

| align="left"| "It's Aw'right" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 126 |

| align="left"| Stax 126 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1963 |

| rowspan="2"| 1963 |

||

| Line 243: | Line 279: | ||

| 87 |

| 87 |

||

| 22 |

| 22 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "[[Walking the Dog]]" |

| align="left"| "[[Walking the Dog]]" |

||

| Line 249: | Line 285: | ||

| align="left"| Stax 140 |

| align="left"| Stax 140 |

||

| 10 |

| 10 |

||

| |

| 4 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="4"| 1964 |

| rowspan="4"| 1964 |

||

| Line 258: | Line 294: | ||

| 48 |

| 48 |

||

| * |

| * |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Somebody Stole My Dog" |

| align="left"| "Somebody Stole My Dog" |

||

| Line 265: | Line 301: | ||

| 86 |

| 86 |

||

| * |

| * |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "That's Really Some Good"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "That's Really Some Good"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

||

| Line 272: | Line 308: | ||

| 92 <small>(A)</small> <br>94 <small>(B)</small> |

| 92 <small>(A)</small> <br>94 <small>(B)</small> |

||

| * |

| * |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Jump Back" |

| align="left"| "Jump Back" |

||

| Line 279: | Line 315: | ||

| 49 |

| 49 |

||

| * |

| * |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="4"| 1965 |

| rowspan="4"| 1965 |

||

| Line 285: | Line 321: | ||

| align="left"| "Baby Walk" |

| align="left"| "Baby Walk" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 167 |

| align="left"| Stax 167 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Willy Nilly" |

| align="left"| "Willy Nilly" |

||

| align="left"| "Sho' Gonna Mess Him Up" |

| align="left"| "Sho' Gonna Mess Him Up" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 173 |

| align="left"| Stax 173 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "When You Move You Lose"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "When You Move You Lose"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| "We're Tight"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "We're Tight"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| Stax 176 |

| align="left"| Stax 176 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Chicken Scratch" |

| align="left"| "Chicken Scratch" |

||

| align="left"| "The World Is Round" |

| align="left"| "The World Is Round" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 178 |

| align="left"| Stax 178 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1966 |

| rowspan="1"| 1966 |

||

| Line 314: | Line 350: | ||

| align="left"| "Never Let You Go"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "Never Let You Go"<br>(<small>as '''Rufus & Carla'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| Stax 184 |

| align="left"| Stax 184 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1967 |

| rowspan="2"| 1967 |

||

| Line 322: | Line 358: | ||

| align="left"| "Talkin' 'Bout True Love" |

| align="left"| "Talkin' 'Bout True Love" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 200 |

| align="left"| Stax 200 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Sophisticated Sissy" |

| align="left"| "Sophisticated Sissy" |

||

| align="left"| "Greasy Spoon" |

| align="left"| "Greasy Spoon" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 221 |

| align="left"| Stax 221 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 43 |

| 43 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="3"| 1968 |

| rowspan="3"| 1968 |

||

| Line 337: | Line 373: | ||

| align="left"| "Steady Holding On" |

| align="left"| "Steady Holding On" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 240 |

| align="left"| Stax 240 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "The Memphis Train" |

| align="left"| "The Memphis Train" |

||

| align="left"| "I Think I Made a Boo-Boo" |

| align="left"| "I Think I Made a Boo-Boo" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 250 |

| align="left"| Stax 250 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Funky Mississippi" |

| align="left"| "Funky Mississippi" |

||

| align="left"| "So Hard to Get Along With" |

| align="left"| "So Hard to Get Along With" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0010 |

| align="left"| Stax 0010 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1969 |

| rowspan="2"| 1969 |

||

| Line 359: | Line 395: | ||

| align="left"| "I Want to Hold You" |

| align="left"| "I Want to Hold You" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0022 |

| align="left"| Stax 0022 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "[[Do the Funky Chicken]]" |

| align="left"| "[[Do the Funky Chicken]]" |

||

| Line 374: | Line 410: | ||

| align="left"| "The Preacher and the Bear" |

| align="left"| "The Preacher and the Bear" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0071 |

| align="left"| Stax 0071 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 42 |

| 42 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "[[(Do the) Push and Pull]] (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "[[(Do the) Push and Pull]] (Part 1)" |

||

| Line 383: | Line 419: | ||

| 25 |

| 25 |

||

| 1 |

| 1 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="3"| 1971 |

| rowspan="3"| 1971 |

||

| Line 389: | Line 425: | ||

| align="left"| "[[I Love You for Sentimental Reasons]]" |

| align="left"| "[[I Love You for Sentimental Reasons]]" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0090 |

| align="left"| Stax 0090 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 34 |

| 34 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "The Breakdown (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "The Breakdown (Part 1)" |

||

| Line 398: | Line 434: | ||

| 31 |

| 31 |

||

| 2 |

| 2 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Do the Funky Penguin (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "Do the Funky Penguin (Part 1)" |

||

| Line 405: | Line 441: | ||

| 44 |

| 44 |

||

| 11 |

| 11 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1972 |

| rowspan="2"| 1972 |

||

| Line 411: | Line 447: | ||

| align="left"| "Love Trap" |

| align="left"| "Love Trap" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0129 |

| align="left"| Stax 0129 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Itch and Scratch (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "Itch and Scratch (Part 1)" |

||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0140 |

| align="left"| Stax 0140 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="3"| 1973 |

| rowspan="3"| 1973 |

||

| Line 426: | Line 462: | ||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0153 |

| align="left"| Stax 0153 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "I Know You Don't Want Me No More" |

| align="left"| "I Know You Don't Want Me No More" |

||

| align="left"| "I'm Still in Love with You" |

| align="left"| "I'm Still in Love with You" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0177 |

| align="left"| Stax 0177 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "That Makes Christmas Day" |

| align="left"| "That Makes Christmas Day" |

||

| align="left"| "I'll Be Your Santa Baby" |

| align="left"| "I'll Be Your Santa Baby" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0187 |

| align="left"| Stax 0187 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1974 |

| rowspan="2"| 1974 |

||

| Line 448: | Line 484: | ||

| align="left"| "Steal a Little" |

| align="left"| "Steal a Little" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0192 |

| align="left"| Stax 0192 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 93 |

| 93 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Boogie Ain't Nuttin' (But Gettin' Down) (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "Boogie Ain't Nuttin' (But Gettin' Down) (Part 1)" |

||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0219 |

| align="left"| Stax 0219 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 63 |

| 63 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1975 |

| rowspan="2"| 1975 |

||

| Line 463: | Line 499: | ||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0236 |

| align="left"| Stax 0236 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 74 |

| 74 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "Jump Back '75 (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "Jump Back '75 (Part 1)" |

||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| Stax 0254 |

| align="left"| Stax 0254 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1976 |

| rowspan="1"| 1976 |

||

| Line 478: | Line 514: | ||

| align="left"| "Blues in the Basement" |

| align="left"| "Blues in the Basement" |

||

| align="left"| Artists of America 126 |

| align="left"| Artists of America 126 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| 92 |

| 92 |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="2"| 1977 |

| rowspan="2"| 1977 |

||

| Line 486: | Line 522: | ||

| align="left"| "Hot Grits" |

| align="left"| "Hot Grits" |

||

| align="left"| AVI 149 |

| align="left"| AVI 149 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| align="left"| "I Ain't Gittin' Older, I'm Gittin' Better (Part 1)" |

| align="left"| "I Ain't Gittin' Older, I'm Gittin' Better (Part 1)" |

||

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

| align="left"| "Part 2" |

||

| align="left"| AVI 178 |

| align="left"| AVI 178 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1978 |

| rowspan="1"| 1978 |

||

| Line 501: | Line 537: | ||

| align="left"| "I Ain't Got Time" |

| align="left"| "I Ain't Got Time" |

||

| align="left"| Hi 78520 |

| align="left"| Hi 78520 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1981 |

| rowspan="1"| 1981 |

||

| Line 509: | Line 545: | ||

| align="left"| "I'd Love to Love You Again" |

| align="left"| "I'd Love to Love You Again" |

||

| align="left"| XL 151 |

| align="left"| XL 151 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1984 |

| rowspan="1"| 1984 |

||

| Line 517: | Line 553: | ||

| align="left"| "Rappin' Rufus (Instrumental Mix)" |

| align="left"| "Rappin' Rufus (Instrumental Mix)" |

||

| align="left"| Ichiban 85-103 |

| align="left"| Ichiban 85-103 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| rowspan="1"| 1998 |

| rowspan="1"| 1998 |

||

| Line 525: | Line 561: | ||

| align="left"| "Body Fine"<br>(<small>by '''[[The Bar-Kays]]'''</small>) |

| align="left"| "Body Fine"<br>(<small>by '''[[The Bar-Kays]]'''</small>) |

||

| align="left"| High Stacks HS9801-7 |

| align="left"| High Stacks HS9801-7 |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

| |

| — |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| colspan="7" style="text-align:center; font-size:9pt;"| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory.<br> * denotes that ''Billboard'' did not publish R&B charts during these chart runs.<ref name=soulfulkindamusic>{{cite web|url=http://www.soulfulkindamusic.net/rthomas.htm|title=Rufus Thomas Discography|publisher=SoulfulKindaMusic.com|access-date=2015-07-17}}</ref> |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Source:<ref name="whitburnr&b"/><ref name=wangdangdula>[http://koti.mbnet.fi/wdd/rufusthomas.htm Rufus Thomas Discography]. Wangdangdula.com. Retrieved 17 July 2015.</ref> |

|||

Source:<ref name="whitburnr&b"/><ref name=wangdangdula>{{cite web|url=http://koti.mbnet.fi/wdd/rufusthomas.htm|title=Rufus Thomas Discography|website=Wangdangdula.com|accessdate=17 July 2015}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 541: | Line 578: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons category}} |

{{commons category}} |

||

*[http://www.alligator.com/artists/bio.cfm?ArtistID=061 Rufus Thomas Biography] at [[Alligator Records]] |

* [http://www.alligator.com/artists/bio.cfm?ArtistID=061 Rufus Thomas Biography] at [[Alligator Records]] |

||

*[http://www.soulwalking.co.uk/Rufus%20Thomas.html Soulwalking.co.uk] |

* [http://www.soulwalking.co.uk/Rufus%20Thomas.html Soulwalking.co.uk] |

||

{{Carla Thomas}} |

{{Carla Thomas}} |

||

| Line 553: | Line 590: | ||

[[Category:2001 deaths]] |

[[Category:2001 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century American singers]] |

[[Category:20th-century American singers]] |

||

[[Category:African-American male singers]] |

[[Category:20th-century African-American male singers]] |

||

[[Category:American male singers]] |

|||

[[Category:American blues singers]] |

[[Category:American blues singers]] |

||

[[Category:American funk singers]] |

[[Category:American funk singers]] |

||

| Line 565: | Line 601: | ||

[[Category:Meteor Records artists]] |

[[Category:Meteor Records artists]] |

||

[[Category:Tennessee State University alumni]] |

[[Category:Tennessee State University alumni]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century male singers]] |

[[Category:20th-century American male singers]] |

||

[[Category:Mississippi Blues Trail]] |

[[Category:Mississippi Blues Trail]] |

||

[[Category:Alligator Records artists]] |

[[Category:Alligator Records artists]] |

||

Latest revision as of 00:30, 1 December 2024

Rufus Thomas | |

|---|---|

Thomas in 1972 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Rufus C. Thomas, Jr. |

| Also known as | Mr. Swing |

| Born | March 26, 1917 Cayce, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | December 15, 2001 (aged 84) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1936–1998 |

| Labels | |

Rufus C. Thomas, Jr. (March 26, 1917 – December 15, 2001)[1][2][3] was an American rhythm-and-blues, funk, soul and blues singer, songwriter, dancer, DJ and comic entertainer from Memphis, Tennessee. He recorded for several labels, including Chess Records and Sun Records in the 1950s, before becoming established in the 1960s and 1970s at Stax Records. His dance records, including "Walking the Dog" (1963), "Do the Funky Chicken" (1969), and "(Do the) Push and Pull" (1970), were some of his most successful songs. According to the Mississippi Blues Commission, "Rufus Thomas embodied the spirit of Memphis music perhaps more than any other artist, and from the early 1940s until his death . . . occupied many important roles in the local scene."[4]

He began his career as a tap dancer, vaudeville performer, and master of ceremonies in the 1930s. He later worked as a disc jockey on radio station WDIA in Memphis, both before and after his recordings became successful. He remained active into the 1990s and as a performer and recording artist was often billed as "The World's Oldest Teenager". He was the father of the singers Carla Thomas (with whom he recorded duets) and Vaneese Thomas and the keyboard player Marvell Thomas.

Early life

[edit]Thomas was born in the rural community of Cayce, Mississippi, on the outskirts of Memphis, Tennessee, the son of a sharecropper. He moved with his family to Memphis around 1920.[4] His mother was a "church woman". Thomas made his debut as a performer at the age of six, playing a frog in a school theatrical production. By the age of 10, he was a tap dancer, performing on the streets and in amateur productions at Booker T. Washington High School, in Memphis.[4][5] From the age of 13, he worked with Nat D. Williams, his high-school history teacher, who was also a pioneer black DJ at radio station WDIA and columnist for black newspapers, as a master of ceremonies at talent shows in the Palace Theater on Beale Street.[5][6] After graduating from high school, Thomas attended Tennessee A&I University for one semester, but economic constraints led him to leave to pursue a career as a full-time entertainer.

Early career

[edit]Thomas began performing in traveling tent shows.[7] In 1936 he joined the Rabbit Foot Minstrels, an all-black revue that toured the South, as a tap dancer and comedian, sometimes part of a duo, Rufus and Johnny.[2] He married Cornelia Lorene Wilson in 1940, at a service officiated by Rev. C. L. Franklin, the father of Aretha Franklin,[8] and the couple settled in Memphis. Thomas worked a day job in the American Finishing Company textile bleaching plant, which he continued to do for over 20 years.[4] He also formed a comedy and dancing duo, Rufus and Bones, with Robert "Bones" Couch, and they took over as MCs at the Palace Theater, often presenting amateur hour shows. One early winner was B.B. King, and others discovered by Thomas later in the 1940s included Bobby Bland and Johnny Ace.[2][5][9]

In the early 1940s, Thomas began writing and performing his own songs. He regarded Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller and Gatemouth Moore as musical influences.[4] He made his professional singing debut at the Elks Club on Beale Street, filling in for another singer at the last minute, and during the 1940s became a regular performer in Memphis nightclubs, such as Currie's Club Tropicana.[4] As an established performer in Memphis, aged 33 in 1950, Thomas recorded his first 78 rpm single, for Jesse Erickson's small Star Talent label in Dallas, Texas. Thomas said, "I just wanted to make a record. I never thought of getting rich. I just wanted to be known, be a recording artist. . . . [But] the record sold five copies and I bought four of them."[10] The record, "I'll Be a Good Boy" backed with "I'm So Worried", gained a Billboard review, which stated that "Thomas shows first class style on a slow blues".[11] He also recorded for the Bullet label in Nashville, Tennessee, when he recorded with Bobby Plater's Orchestra and was credited as "Mr. Swing"; the recordings were not recognised by researchers as being by Thomas until 1996.[12] In 1951 he made his first recordings at Sam Phillips's Sun Studio, for the Chess label, but they were not commercially successful.[12][13]

He began working as a DJ at radio station WDIA in 1951, and hosted an afternoon R&B show called Hoot and Holler. WDIA, featuring an African-American format, was known as "the mother station of the Negroes" and became an important source of blues and R&B music for a generation, its audience consisting of white as well as black listeners. Thomas used to introduce his shows saying, "I'm young, I'm loose, I'm full of juice, I got the goose so what's the use. We're feeling gay though we ain't got a dollar, Rufus is here, so hoot and holler."[14] He also used to lead tours of white teenagers on "midnight rambles" around Beale Street.[14] Thomas claimed to be the first black DJ to play Elvis Presley records, which he did until the station program director made him stop due to segregation. Shortly thereafter, Thomas performed on stage with Elvis to an all-black audience and the audience stormed through to get to him. After that, the program director allowed Elvis songs to be played on WDIA.[14]

His celebrity in the South was such that in 1953, at Sam Phillips's suggestion, he recorded "Bear Cat" for Sun Records, an "answer record" to Big Mama Thornton's R&B hit "Hound Dog".[2] The record became the label's first national chart hit, reaching number 3 on the Billboard R&B chart. However, a copyright-infringement suit brought by Don Robey, the original publisher of "Hound Dog", nearly bankrupted the record label.[2] After only one recording there, Thomas was one of the African-American artists released by Phillips,[2] as he oriented his label more toward white audiences and signed Elvis Presley, who later recorded Thomas's song "Tiger Man".[6][15][16] Thomas did not record again until 1956, when he made a single, "I'm Steady Holdin' On", for the Bihari brothers' Meteor label; musicians on the record included Lewie Steinberg, later a founding member of Booker T and the MGs.[12]

Stax Records

[edit]In 1960 he made his first recordings with his 17-year-old daughter Carla, for the Satellite label in Memphis, which changed its name to Stax the following year. The song, "Cause I Love You", featuring a rhythm borrowed from Jesse Hill's "Ooh Poo Pa Doo", was a regional hit; the musicians included Thomas' son Marvell on keyboards, Steinberg, and the 16-year-old Booker T. Jones.[6][8] The record's success led to Stax gaining production and distribution deal with the much larger Atlantic Records.[4]

Rufus Thomas continued to record for the label after Carla's record "Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)" reached the national R&B chart in 1961. He had his own hit with "The Dog", a song he had originally improvised in performance based on a Willie Mitchell bass line, complete with imitations of a barking dog. The 1963 follow-up, "Walking the Dog", engineered by Tom Dowd of Atlantic, became one of his most successful records, reaching #10 on the Billboard pop chart.[2][5][17][18] He became the first, and still the only, father to debut in the Top 10 after his daughter had first appeared there. The song was recorded in early 1964 by the Rolling Stones on their debut album, and was a minor UK chart hit for Merseybeat group the Dennisons later that year.[19]

As well as recording and appearing on radio and in clubs, Thomas continued to work as a boiler operator in the textile plant, where he claimed the noises sometimes suggested musical rhythms and lyrics to him, before he finally gave up the job in 1963,[4] to focus on his role as a singer and entertainer. He recorded a series of novelty dance tracks, including "Can Your Monkey Do the Dog'" and '"Somebody Stole My Dog" for Stax, where he was often backed by Booker T. & the MGs or the Bar-Kays. He also became a mentor to younger Stax stars,[2] giving advice on stage moves to performers like Otis Redding, who partnered daughter Carla on record.[5]

After "Jump Back" in 1964, the hits dried up for several years, as Stax gave more attention to younger artists and musicians. However, in 1970 he had another big hit with "Do the Funky Chicken", which reached #5 on the R&B chart, #28 on the pop chart, and #18 in Britain where it was his only chart hit.[20] Thomas improvised the song while performing with Willie Mitchell's band at a club in Covington, Tennessee, including a spoken word section that he regularly used as a shtick as a radio DJ: "Oh I feel so unnecessary - this is the kind of stuff that makes you feel like you wanna do something nasty, like waste some chicken gravy on your white shirt right down front." The recording was produced by Al Bell and Tom Nixon, and used the Bar-Kays, featuring guitarist Michael Toles. Thomas continued to work with Bell and Nixon as producers, and later in 1970 had his only number 1 R&B hit [and his second-highest pop charting record] with another dance song, "Do the Push and Pull".[18][21] A further dance-oriented release in 1971, "The Breakdown", climbed to number 2 R&B and number 31 Pop. In 1972, he featured in the Wattstax concert, and he had several further, less successful, hits before Stax collapsed in 1976.[2][5]

Later career

[edit]Thomas continued to record and toured internationally, billing himself as "The World's Oldest Teenager" and describing himself as "the funkiest man alive".[9] He "drew upon his vaudeville background to put [his songs] over on stage with fancy footwork that displayed remarkable agility for a man well into his fifties",[2] and usually performed "while clothed in a wardrobe of hot pants, boots and capes, all in wild colors."[4]

He continued as a DJ at WDIA until 1974, and worked for a period at WLOK before returning to WDIA in the mid-1980s to co-host a blues show.[4] He appeared regularly on television and recorded albums for various labels.[5] Thomas performed regularly at the Porretta Soul Festival in Italy; the outdoor amphitheater in which he performed was later renamed Rufus Thomas Park.[7]

He played an important part in the Stax reunion of 1988, and appeared in Jim Jarmusch's 1989 film Mystery Train, Robert Altman's 1999 film Cookie's Fortune, and D. A. Pennebaker’s documentary Only the Strong Survive.[2][4] Thomas released an album of straight-ahead blues, That Woman Is Poison!, with Alligator Records in 1988, featuring saxophonist Noble "Thin Man" Watts.[9] In 1996, he and William Bell headlined at the Olympics in Atlanta, Georgia. In 1997, he released an album, Rufus Live!, on Ecko Records. In 1998, he hosted two New Year's Eve shows on Beale Street.[7]

In 1997, to commemorate his 80th birthday, the City of Memphis renamed a road off Beale Street, close to the old Palace Theater, as Rufus Thomas Boulevard.[5] He received a Pioneer Award from the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1992, and a lifetime achievement award from ASCAP in 1997.[5] He was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2001.[2]

Death and legacy

[edit]

He died of heart failure in 2001, at the age of 84, at St. Francis Hospital in Memphis.[2] He is buried next to his wife Lorene, who died in 2000, at the New Park Cemetery in Memphis.

Writer Peter Guralnick said of him:[6]

His music... brought a great deal of joy to the world, but his personality brought even more, conveying a message of grit, determination, indomitability, above all a bottomless appreciation for the human comedy that left little room for the drab or the dreary in his presence.

Thomas was honored with a marker on the Mississippi Blues Trail in Byhalia.[4]

In popular culture

[edit]Bobby Brown portrays Thomas in the BET television series American Soul.

A character named Rufus in “Kill Bill: Volume 2” played with Rufus Thomas.[citation needed]

His name is referenced on the Beastie Boys album Check Your Head.

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]| Year | Title | Catalogue ref | Peak chart positions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US 200 [22] |

US R&B [22] | ||||

| 1963 | Walking the Dog | Stax 704[23] | 138 | — | |

| 1970 | Do the Funky Chicken | Stax STS-2028[24] | — | 32 | |

| Rufus Thomas Live: Doing the Push & Pull at P.J.'s | Stax STS-2039[25] | 147 | 19 | ||

| 1972 | Did You Heard Me? | Stax STS-3004[26] | — | — | |

| 1973 | Crown Prince of Dance | Stax STS-3008[27] | — | 42 | |

| 1977 | If There Were No More Music | AVI 6015[28] | — | — | |

| 1978 | I Ain't Gettin' Older, I'm Gettin' Better | AVI 6046[29] | — | — | |

| 1988 | That Woman Is Poison! | Alligator AL 4769[30] | — | — | |

| 1996 | Blues Thang! | Sequel/Castle SEQ 1054 | — | — | |

| The Best of Rufus Thomas: Do the Funky Somethin' (compilation) | Rhino R2 72410 | — | — | ||

| 1997 | Rufus Live! [rec. 1996 at Southern Crossroads Festival in Atlanta, GA] | Ecko ECD 1013 | — | — | |

| 2000 | Swing Out with Rufus Thomas | High Stacks HS 9982 | — | — | |

| 2005 | Just Because I'm Leavin' (posthumous) | Segue Records SRRT05 | — | — | |

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. | |||||

Source:[31]

Singles

[edit]| Year | A-side | B-side | Catalogue no. | Chart positions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Pop [32] |

US R&B [18] |

UK [20] | ||||

| 1950 | "I'll Be a Good Boy" | "I'm So Worried" | Star Talent 807 | — | — | — |

| "Gonna Bring My Baby Back" (as Mr. Swing with Bobby Plater's Orchestra)[33] |

"Beer Bottle Boogie" (as Mr. Swing with Bobby Plater's Orchestra) |

Bullet 327 | — | — | — | |

| 1951 | "Night Walkin' Blues" | "Why Did You Dee Gee" | Chess 1466 | — | — | — |

| 1952 | "No More Doggin' Around" | "Crazy 'Bout You, Baby" | Chess 1492 | — | — | — |

| "Juanita" | "Decorate the Counter" | Chess 1517 | — | — | — | |

| 1953 | "Bear Cat" | "Walking in the Rain" | Sun 181 | — | 3 | — |

| "Tiger Man (King of the Jungle)" | "Save Your Money" | Sun 188 | — | — | — | |

| 1956 | "I'm Steady Holdin' On" | "The Easy Livin' Plan" | Meteor 5039 | — | — | — |

| 1960 | "Cause I Love You" (as Carla [Thomas] and Rufus) |

"Deep Down Inside" (as Carla and Rufus) |

Satellite 102; Atco 6177 |

— | — | — |

| 1961 | "I Didn't Believe" (as Rufus and Friend [Carla]) |

"Yeah, Yea-Ah" (as Rufus and Friend) |

Atco 6199 | — | — | — |

| 1962 | "Can't Ever Let You Go" | "It's Aw'right" | Stax 126 | — | — | — |

| 1963 | "The Dog" | "Did You Ever Love a Woman" | Stax 130 | 87 | 22 | — |

| "Walking the Dog" | "You Said" ("Fine & Mellow" on some early copies) |

Stax 140 | 10 | 4 | — | |

| 1964 | "Can Your Monkey Do the Dog" | "I Wanna Get Married" | Stax 144 | 48 | * | — |

| "Somebody Stole My Dog" | "I Want to Be Loved" | Stax 149 | 86 | * | — | |

| "That's Really Some Good" (as Rufus & Carla) |

"Night Time Is the Right Time" (as Rufus & Carla) |

Stax 151 | 92 (A) 94 (B) |

* | — | |

| "Jump Back" | "All Night Worker" | Stax 157 | 49 | * | — | |

| 1965 | "Little Sally Walker" | "Baby Walk" | Stax 167 | — | — | — |

| "Willy Nilly" | "Sho' Gonna Mess Him Up" | Stax 173 | — | — | — | |

| "When You Move You Lose" (as Rufus & Carla) |

"We're Tight" (as Rufus & Carla) |

Stax 176 | — | — | — | |

| "Chicken Scratch" | "The World Is Round" | Stax 178 | — | — | — | |

| 1966 | "Birds and Bees" (as Rufus & Carla) |

"Never Let You Go" (as Rufus & Carla) |

Stax 184 | — | — | — |

| 1967 | "Sister's Got a Boyfriend" | "Talkin' 'Bout True Love" | Stax 200 | — | — | — |

| "Sophisticated Sissy" | "Greasy Spoon" | Stax 221 | — | 43 | — | |

| 1968 | "Down ta My House" | "Steady Holding On" | Stax 240 | — | — | — |

| "The Memphis Train" | "I Think I Made a Boo-Boo" | Stax 250 | — | — | — | |

| "Funky Mississippi" | "So Hard to Get Along With" | Stax 0010 | — | — | — | |

| 1969 | "Funky Way" | "I Want to Hold You" | Stax 0022 | — | — | — |

| "Do the Funky Chicken" | "Turn Your Damper Down" | Stax 0059 | 28 | 5 | 18 | |

| 1970 | "Sixty Minute Man" | "The Preacher and the Bear" | Stax 0071 | — | 42 | — |

| "(Do the) Push and Pull (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0079 | 25 | 1 | — | |

| 1971 | "The World Is Round" | "I Love You for Sentimental Reasons" | Stax 0090 | — | 34 | — |

| "The Breakdown (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0098 | 31 | 2 | — | |

| "Do the Funky Penguin (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0112 | 44 | 11 | — | |

| 1972 | "6-3-8 (That's the Number to Play)" | "Love Trap" | Stax 0129 | — | — | — |

| "Itch and Scratch (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0140 | — | — | — | |

| 1973 | "Funky Robot (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0153 | — | — | — |

| "I Know You Don't Want Me No More" | "I'm Still in Love with You" | Stax 0177 | — | — | — | |

| "That Makes Christmas Day" | "I'll Be Your Santa Baby" | Stax 0187 | — | — | — | |

| 1974 | "The Funky Bird" | "Steal a Little" | Stax 0192 | — | 93 | — |

| "Boogie Ain't Nuttin' (But Gettin' Down) (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0219 | — | 63 | — | |

| 1975 | "Do the Double Bump (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0236 | — | 74 | — |

| "Jump Back '75 (Part 1)" | "Part 2" | Stax 0254 | — | — | — | |