Battle of Bushy Run: Difference between revisions

Srich32977 (talk | contribs) m Fixed typo Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App section source |

citation to support location of battle (Edge Hill) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| commander1 = [[Guyasuta]]<br /> [[Keekyuscung]]{{KIA}} |

| commander1 = [[Guyasuta]]<br /> [[Keekyuscung]]{{KIA}} |

||

| commander2 = [[Henry Bouquet]] |

| commander2 = [[Henry Bouquet]] |

||

| strength1 = 110–500<ref name="Brumwell, p 220">Brumwell, p 220</ref><ref>''Profiles in American History: Exploration to Revolution''; Joyce Moss and George Wilson; UXL, 1993; |

| strength1 = 110–500<ref name="Brumwell, p 220">Brumwell, p 220</ref><ref>''Profiles in American History: Exploration to Revolution''; Joyce Moss and George Wilson; UXL, 1993; p. 149</ref> |

||

| strength2 = 500 |

| strength2 = 500 |

||

| casualties1 = 20–60 killed |

| casualties1 = 20–60 killed |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

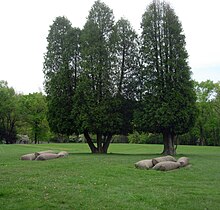

[[Image:EdgeHillBushyRunPA.jpg|thumb|Concrete flour bags at the Bushy Run Battlefield monument on Edge Hill.]] |

[[Image:EdgeHillBushyRunPA.jpg|thumb|Concrete flour bags at the Bushy Run Battlefield monument on Edge Hill.]] |

||

[[File:Bushy Run battle historical marker, Jeanette PA USA.jpg|thumb|Historical marker, US Route 30, Jeanette PA USA]] |

|||

According to one account, the allied tribes attacked in the morning, but were themselves ambushed by the sentries relieved from their evening duty. With the surprise attack of the sentries, from a flank, and a frontal assault by the main British column, the outnumbered Indians fled in a disorganized retreat. |

According to one account, the allied tribes attacked in the morning, but were themselves ambushed by the sentries relieved from their evening duty. With the surprise attack of the sentries, from a flank, and a frontal assault by the main British column, the outnumbered Indians fled in a disorganized retreat. |

||

| Line 36: | Line 37: | ||

A second account holds that the warriors attacked in the morning and "redoubled their efforts to break the British line." As the tribesmen became bolder, Bouquet realized the combat was nearing a crisis. Determined to lure his attackers close enough to maim them, the British leader deliberately weakened one section of his line. Spotting the gap in the enemy defenses, the native warriors rushed forward. Instead, the British soldiers fired a volley in their faces and "made terrible havock" with the bayonet. The surviving warriors fled and were unable to rally.<ref>Brumwell, pp. 220–221</ref> This account concurs with that written by [[Richard Cannon]] in 1845 in the history of the 42nd Highlanders Regiment in which says that the Colonel of the regiment called in his posts as if about to retreat and the Indians believing that they had victory rushed forward from behind their cover becoming fully exposed.<ref name="Cannon"/> They were then instantly charged in the front and in the flank, by two companies of the 42nd Highlanders, and were thrown into confusion and routed.<ref name="Cannon"/> |

A second account holds that the warriors attacked in the morning and "redoubled their efforts to break the British line." As the tribesmen became bolder, Bouquet realized the combat was nearing a crisis. Determined to lure his attackers close enough to maim them, the British leader deliberately weakened one section of his line. Spotting the gap in the enemy defenses, the native warriors rushed forward. Instead, the British soldiers fired a volley in their faces and "made terrible havock" with the bayonet. The surviving warriors fled and were unable to rally.<ref>Brumwell, pp. 220–221</ref> This account concurs with that written by [[Richard Cannon]] in 1845 in the history of the 42nd Highlanders Regiment in which says that the Colonel of the regiment called in his posts as if about to retreat and the Indians believing that they had victory rushed forward from behind their cover becoming fully exposed.<ref name="Cannon"/> They were then instantly charged in the front and in the flank, by two companies of the 42nd Highlanders, and were thrown into confusion and routed.<ref name="Cannon"/> |

||

Having dispersed its attackers, Bouquet's column headed to [[Bushy Run (Pennsylvania)|Bushy Run]], a mile along the Forbes road, where there was badly needed water. The battle has since been attributed to the Bushy Run location, despite the main fighting taking place in Edge Hill. Bouquet then marched to the relief of Fort Pitt. |

Having dispersed its attackers, Bouquet's column headed to [[Bushy Run (Pennsylvania)|Bushy Run]], a mile along the Forbes road, where there was badly needed water. The battle has since been attributed to the Bushy Run location, despite the main fighting taking place in Edge Hill.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ockershausen |first1=Jane |title=Broken Promises, Broken Dreams: North America's Forgotten Conflict at Bushy Run Battlefield |journal=Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine via Wayback Machine |date=Summer 1997 |volume=XXII |issue=3 |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060320191314/http://www.phmc.state.pa.us/ppet/bushyrun/page1.asp?secid=31 |access-date=4 December 2024}}</ref> Bouquet then marched to the relief of Fort Pitt. |

||

==Aftermath== |

==Aftermath== |

||

[[File:John Peebles, memorial plaque, Irvine.JPG|thumb|250px|Memorial plaque to John Peebles in the Old Parish Church ([[Irvine, North Ayrshire]]) who was wounded at the Battle of Bushy Run.]] |

[[File:John Peebles, memorial plaque, Irvine.JPG|thumb|250px|Memorial plaque to John Peebles in the Old Parish Church ([[Irvine, North Ayrshire]]) who was wounded at the Battle of Bushy Run.]] |

||

The battle cost the lives of 50 British soldiers, including 29 of the 42nd Highlanders, seven of the 60th Royal Americans, six of the 77th Highlanders, and eight [[civilians]] and volunteers.<ref name="Warren"/> The confederacy of the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, and Huron suffered an unknown number of casualties, which includes two prominent Delaware chiefs; estimates by contemporaries placed the total Indian loss at about 60.<ref>Warren and |

The battle cost the lives of 50 British soldiers, including 29 of the 42nd Highlanders, seven of the 60th Royal Americans, six of the 77th Highlanders, and eight [[civilians]] and volunteers.<ref name="Warren"/> The confederacy of the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, and Huron suffered an unknown number of casualties, which includes two prominent Delaware chiefs; estimates by contemporaries placed the total Indian loss at about 60.<ref>Warren and Son, p. 24</ref> The warrior Killbuck later told [[Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet|Sir William Johnson]] that only 110 Indians were engaged. Bouquet estimated he fought an equal number as his own force.<ref name="Brumwell, p 220"/> One contemporary report claimed 20 Indians were killed and many more wounded. The result of the battle inspired in the British "widespread relief on the frontier", since the Indians had finally been defeated on their own ground, prompting one newspaper to exclaim, "that Indians are no more invulnerable than other Men, when attacked on equal Terms, and especially by British Troops."<ref>Brumwell, p. 221</ref> |

||

The site of the battle is now [[Bushy Run Battlefield Park]]. |

The site of the battle is now [[Bushy Run Battlefield Park]]. |

||

| Line 49: | Line 50: | ||

===Printed materials=== |

===Printed materials=== |

||

* Brumwell, Stephen. ''Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, |

* Brumwell, Stephen. ''Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755–1763''. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002. {{ISBN|0-521-80783-2}} |

||

* Nester, William R. ''"Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763''. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000. {{ISBN|0-275-96770-0}}. |

* Nester, William R. ''"Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763''. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000. {{ISBN|0-275-96770-0}}. |

||

* Warren and |

* Warren and Son, Lieut-General Sir Edward Hutton. ''Colonel Henry Bouquet: A Biographical Sketch''. 1911 |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Latest revision as of 13:05, 4 December 2024

| Battle of Bushy Run | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Pontiac's Rebellion | |||||||

Highlanders charge at Bushy Run | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Ohio Country natives | Great Britain | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Guyasuta Keekyuscung † | Henry Bouquet | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 110–500[1][2] | 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20–60 killed |

42nd Highlanders: 50 killed 36 wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Bushy Run was fought on August 5–6, 1763, in western Pennsylvania, between a British column under the command of Colonel Henry Bouquet and a combined force of Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, and Huron warriors. This action occurred during Pontiac's Rebellion. Though the British suffered serious losses, they routed the tribesmen and successfully relieved the garrison of Fort Pitt.

Battle

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

In July 1763, a relief column of 500 British soldiers, including the 42nd Highlanders, 60th Royal Americans, and 77th Highlanders, left Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to relieve Fort Pitt, then under siege. Indian scouts observed Bouquet's force marching west along Forbes Road and reported this to the Indians surrounding Fort Pitt. On August 5, at about 1:00 pm,[5] a part of the force besieging Fort Pitt ambushed the British column one mile east of Bushy Run Station, at Edge Hill. The British managed to hold their ground until after sunset, when the natives withdrew. Bouquet ordered a redoubt constructed on Edge Hill, and the British placed their wounded and livestock in the center of the perimeter.

According to one account, the allied tribes attacked in the morning, but were themselves ambushed by the sentries relieved from their evening duty. With the surprise attack of the sentries, from a flank, and a frontal assault by the main British column, the outnumbered Indians fled in a disorganized retreat.

A second account holds that the warriors attacked in the morning and "redoubled their efforts to break the British line." As the tribesmen became bolder, Bouquet realized the combat was nearing a crisis. Determined to lure his attackers close enough to maim them, the British leader deliberately weakened one section of his line. Spotting the gap in the enemy defenses, the native warriors rushed forward. Instead, the British soldiers fired a volley in their faces and "made terrible havock" with the bayonet. The surviving warriors fled and were unable to rally.[6] This account concurs with that written by Richard Cannon in 1845 in the history of the 42nd Highlanders Regiment in which says that the Colonel of the regiment called in his posts as if about to retreat and the Indians believing that they had victory rushed forward from behind their cover becoming fully exposed.[3] They were then instantly charged in the front and in the flank, by two companies of the 42nd Highlanders, and were thrown into confusion and routed.[3]

Having dispersed its attackers, Bouquet's column headed to Bushy Run, a mile along the Forbes road, where there was badly needed water. The battle has since been attributed to the Bushy Run location, despite the main fighting taking place in Edge Hill.[7] Bouquet then marched to the relief of Fort Pitt.

Aftermath

[edit]

The battle cost the lives of 50 British soldiers, including 29 of the 42nd Highlanders, seven of the 60th Royal Americans, six of the 77th Highlanders, and eight civilians and volunteers.[4] The confederacy of the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, and Huron suffered an unknown number of casualties, which includes two prominent Delaware chiefs; estimates by contemporaries placed the total Indian loss at about 60.[8] The warrior Killbuck later told Sir William Johnson that only 110 Indians were engaged. Bouquet estimated he fought an equal number as his own force.[1] One contemporary report claimed 20 Indians were killed and many more wounded. The result of the battle inspired in the British "widespread relief on the frontier", since the Indians had finally been defeated on their own ground, prompting one newspaper to exclaim, "that Indians are no more invulnerable than other Men, when attacked on equal Terms, and especially by British Troops."[9]

The site of the battle is now Bushy Run Battlefield Park.

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Brumwell, p 220

- ^ Profiles in American History: Exploration to Revolution; Joyce Moss and George Wilson; UXL, 1993; p. 149

- ^ a b c d e f Cannon, Richard. (1845). Historical record of the Forty-second, or, the Royal Highland Regiment of Foot : containing an account of the formation of six companies of Highlanders in 1729 ... and were regimented in 1739 and of the subsequent services of the regiment to 1844. p. 60

- ^ a b c d Warren and son, p. 24.

- ^ "Colonel Henry Bouquet a biographical sketch:" Lieut-General Sir Edward Hutton Warren and son 1911. p. 22.

- ^ Brumwell, pp. 220–221

- ^ Ockershausen, Jane (Summer 1997). "Broken Promises, Broken Dreams: North America's Forgotten Conflict at Bushy Run Battlefield". Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine via Wayback Machine. XXII (3). Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Warren and Son, p. 24

- ^ Brumwell, p. 221

Printed materials

[edit]- Brumwell, Stephen. Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755–1763. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-80783-2

- Nester, William R. "Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000. ISBN 0-275-96770-0.

- Warren and Son, Lieut-General Sir Edward Hutton. Colonel Henry Bouquet: A Biographical Sketch. 1911

External links

[edit]- "Broken Promises, Broken Dreams: North America's Forgotten Conflict at Bushy Run Battlefield" (article originally from Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine)

- "Battle of Bushy Run" from mohicanpress.com