Otti Berger: Difference between revisions

Added information to education about her schooling and book publication. Created an "Impact" paragraph. Added information about where her works were published, how this influenced the people around her, and which museums her work can still be found in today. |

Mistico Dois (talk | contribs) m Minor edit. |

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|Hungarian textile artist and weaver}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2015}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2015}} |

||

{{Infobox artist |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| name = Otti Berger |

|||

| ⚫ | '''Otti Berger''' (Otilija Ester Berger) |

||

| image = OttiBerger (cropped - Otti Berger).jpg |

|||

| caption = Otti Berger (1930) |

|||

| birth_name = Otilija Ester Berger |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1898|10|4|}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Zmajevac|Zmajevac, Croatia]], [[Austria-Hungary]] |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age |1944|5|3|1898|10|4|}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Auschwitz concentration camp|Auschwitz]], [[Poland]] |

|||

| field = [[Textiles]]<br>[[weaving]] |

|||

| training = [[Bauhaus]] |

|||

| spouse = |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ | '''Otti Berger''' (Otilija Ester Berger) (4 October 1898, in present-day [[Zmajevac|Zmajevac, Croatia]] - 3 May 1944) was a Croatian student and later teacher at the [[Bauhaus]], where she was a [[Textile arts|textile artist]] and [[Weaving|weaver]]. She was murdered in 1944 at [[Auschwitz concentration camp|Auschwitz]] during [[the Holocaust]]. |

||

| ⚫ | {{Blockquote|text=The handle of stuff is of primary importance. A piece of stuff must be touched and felt; it has to be held in the hands. The beauty of a stuff is above all, known by its feel. The feel of stuff in the hands can be just as beautiful an experience as colour can be to the eye or sound to the ear.|author=Otti Berger|title="Stoffe im Raum", or "Fabric for the Home"}}<ref>{{ |

||

== |

==Early life== |

||

Otti Berger was born on 4 October 1898 in present-day Zmajevac, Croatia. At the time of Berger’s birth, Zmajevac was part of the Baranya region of Austro-Hungary and was known as Vörösmart. Berger’s Jewish family was granted unrestricted residence and freedom in religion under the rule of [[Franz Joseph I of Austria|Emperor Franz Joseph |

Otti Berger was born on 4 October 1898 in present-day Zmajevac, Croatia. At the time of Berger’s birth, Zmajevac was part of the Baranya region of Austro-Hungary and was known as Vörösmart. Berger’s Jewish family was granted unrestricted residence and freedom in religion under the rule of [[Franz Joseph I of Austria|Emperor Franz Joseph I]]. Because of Vörösmart’s national transition from Austro-Hungarian to Yugoslavian in 1918, and later Croatian, Berger’s nationality was and still is often mistaken. Though a native Hungarian speaker, Berger was also fluent in German. Due to a previous illness, Berger suffered from partial hearing loss, which was said to have heightened or enhanced her sense of touch.<ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Otto |first=Elizabeth |title=Bauhaus women : a global perspective |date=2019 |others=Patrick Rössler |isbn=978-1-912217-96-0 |location=London, UK |oclc=1084302497 }}{{pn|date=October 2023}}</ref> |

||

==Education== |

==Education== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Berger was born in [[Zmajevac]] in [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian Empire]] (present-day [[Croatia]]).<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url = http://bauhaus-online.de/en/magazin/artikel/otti-berger-croatian-artist-from-the-bauhaus-textile-worksho|title = Otti Berger – Croatian Artist from the Bauhaus Textile Workshop {{!}} Bauhaus Online|website = bauhaus-online.de|access-date = 2016-03-04}}</ref> She completed education at the Collegiate School for Girls in Vienna before enrolling in the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, now the [[Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb]]. She continued her studies in [[Zagreb]] until 1926 before attending [[Bauhaus]] in [[Dessau]], Germany.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url = http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger|title = Otti Berger {{!}} Bauhaus Online|website = bauhaus-online.de|access-date = 2016-03-04}}</ref> There, Berger studied under [[László Moholy-Nagy]], [[Paul Klee]], and [[Wassily Kandinsky]], among others. Berger has been described as "one of the most talented students at the weaving workshop in Dessau."<ref>Weibel, Peter. ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=xkk6U42Zl_sC&q=Otti+Berger+artist Beyond Art: A Third Culture. A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary]''. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 2005. p. 76</ref> |

Berger was born in [[Zmajevac]] in [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian Empire]] (present-day [[Croatia]]).<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url = http://bauhaus-online.de/en/magazin/artikel/otti-berger-croatian-artist-from-the-bauhaus-textile-worksho|title = Otti Berger – Croatian Artist from the Bauhaus Textile Workshop {{!}} Bauhaus Online|website = bauhaus-online.de|access-date = 2016-03-04|archive-date = July 7, 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160707003043/http://bauhaus-online.de/en/magazin/artikel/otti-berger-croatian-artist-from-the-bauhaus-textile-worksho|url-status = dead}}</ref> She completed education at the Collegiate School for Girls in Vienna before enrolling in the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, now the [[Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb]]. She continued her studies in [[Zagreb]] until 1926 before attending [[Bauhaus]] in [[Dessau]], Germany.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url = http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger|title = Otti Berger {{!}} Bauhaus Online|website = bauhaus-online.de|access-date = 2016-03-04|archive-date = June 27, 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160627235744/http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger|url-status = dead}}</ref> There, Berger studied under [[László Moholy-Nagy]], [[Paul Klee]], and [[Wassily Kandinsky]], among others. Berger has been described as "one of the most talented students at the weaving workshop in Dessau."<ref>Weibel, Peter. ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=xkk6U42Zl_sC&q=Otti+Berger+artist Beyond Art: A Third Culture. A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary]''. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 2005. p. 76</ref> |

||

[[File:Book MET DP10028.jpg|alt=blue and white rectangular fabric pattern|thumb|Sample textile designed by Otti Berger]] |

[[File:Book MET DP10028.jpg|alt=blue and white rectangular fabric pattern|thumb|Sample textile designed by Otti Berger]] |

||

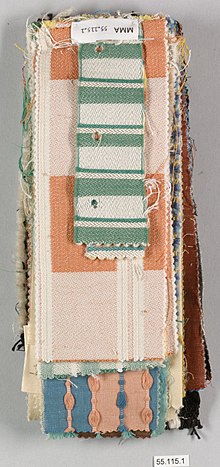

[[File:Book MET DP10030.jpg|alt=fabric swatches|thumb|Sample textile book of 22 various designs by Berger using synthetic dyes and mercerized cotton.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/488834|title=Otti Berger. Book. The Met|website=www.metmuseum.org|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref>]] |

[[File:Book MET DP10030.jpg|alt=fabric swatches|thumb|Sample textile book of 22 various designs by Berger using synthetic dyes and mercerized cotton.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/488834|title=Otti Berger. Book. The Met|website=www.metmuseum.org|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref>]] |

||

A core member of the experimental approach to textiles at the Bauhaus,<ref name=Smith> |

A core member of the experimental approach to textiles at the Bauhaus,<ref name=Smith>{{cite book |last1=Smith |first1=T’ai |title=Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design |date=2014 |publisher=University of Minnesota Press |id={{Project MUSE|35700|type=book}} |isbn=978-1-4529-4323-7 }}{{pn|date=October 2023}}</ref> Berger experimented with methodology and materials during the course of her studies at the Bauhaus to eventually include plastic textiles intended for mass production.<ref name="Beyond">Weibel, Peter. ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=xkk6U42Zl_sC&q=Otti+Berger+artist Beyond Art: A Third Culture. A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary]''. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 2005.</ref> Along with [[Anni Albers]] and [[Gunta Stölzl]], Berger pushed back against the understanding of textiles as a feminine craft and utilized rhetoric used in photography and painting to describe her work.<ref name=Smith/> During her time in [[Dessau]], she also wrote a treatise on fabrics and the methodology of textile production, which stayed with [[Walter Gropius]] and was never published.<ref name="Beyond"/> |

||

In 1929, Berger attended classes at Praktiska Vävnadsskolan in Stockholm where she wrote a nine-page thesis about Swedish Weaving techniques called 'Schwedische Bindungslehre', which later influenced her published weaving instructing booklet, ''[[:de:Bindungslehre|Bindungslehre]].''<ref name=":3" /> |

In 1929, Berger attended classes at Praktiska Vävnadsskolan in Stockholm where she wrote a nine-page thesis about Swedish Weaving techniques called 'Schwedische Bindungslehre', which later influenced her published weaving instructing booklet, ''[[:de:Bindungslehre|Bindungslehre]].''<ref name=":3" /> |

||

In 1931, Berger became the new head of weaving at the Bauhaus under the advisement of Stolzl, who had resigned from the position. She began to create her own curriculum, and acted as a mentor to younger Bauhaus students who carried on Bauhaus methods, including Paris-based weaver Zsuzsa Markos-Ney and {{Interlanguage link multi|Etel Fodor-Mittag|de|}}, who became a hand weaver in South Africa.<ref name="Beyond" /><ref name=":1" /> It was a short-lived position, however, as she was replaced in 1932 by [[Lilly Reich]], the partner of new |

In 1931, Berger became the new head of weaving at the Bauhaus under the advisement of Stolzl, who had resigned from the position. She began to create her own curriculum, and acted as a mentor to younger Bauhaus students who carried on Bauhaus methods, including Paris-based weaver Zsuzsa Markos-Ney and {{Interlanguage link multi|Etel Fodor-Mittag|de|}}, who became a hand weaver in South Africa.<ref name="Beyond" /><ref name=":1" /> It was a short-lived position, however, as she was replaced in 1932 by [[Lilly Reich]], the partner of new Bauhaus director [[Ludwig Mies van der Rohe]].<ref name=":4" /> |

||

== |

==Career== |

||

When the Bauhaus closed under German force in 1932, Berger opened her own textile design studio, "otti berger atelier für textilien," which she ran from her apartment in Berlin using looms she purchased from the school's weaving workshop.<ref name=":4" /> There, her goal was to produce textiles for use in industry. She secured contracts with several design firms, including Wohnbedarf AG, a Swedish design company, and worked with manufacturers C.F. Baumgärtel & Sohn, Schriever and Websky, as well as Hartmann and Wiesen.<ref name=":2">{{ |

When the Bauhaus closed under German force in 1932, Berger opened her own textile design studio, "otti berger atelier für textilien," which she ran from her apartment in Berlin using looms she purchased from the school's weaving workshop.<ref name=":4" /> There, her goal was to produce textiles for use in industry. She secured contracts with several design firms, including Wohnbedarf AG, a Swedish design company, and worked with manufacturers C.F. Baumgärtel & Sohn, Schriever and Websky, as well as Hartmann and Wiesen.<ref name=":2">{{cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=T'ai |title=Anonymous Textiles, Patented Domains: The Invention (and Death) of an Author |journal=Art Journal |date=June 2008 |volume=67 |issue=2 |pages=54–73 |doi=10.1080/00043249.2008.10791304 |s2cid=191345039 }}</ref> |

||

Berger was interested in authoring her own work and making a name for herself as a designer of woven textiles, which is uncommon in the industrial textile production field. She went so far as to begin signing her woven works with her initials in lowercase, “o.b.” In 1932, while working on designs for Wohnbedarf AG, Berger pushed for recognition, in fear that her work would be subjected to anonymity within the large design company. She asked that her prototypes be attached to the name “Otti Berger-Stoffe”, a request which was granted by Wohnbedarf.<ref name=":2" /> |

Berger was interested in authoring her own work and making a name for herself as a designer of woven textiles, which is uncommon in the industrial textile production field. She went so far as to begin signing her woven works with her initials in lowercase, “o.b.” In 1932, while working on designs for Wohnbedarf AG, Berger pushed for recognition, in fear that her work would be subjected to anonymity within the large design company. She asked that her prototypes be attached to the name “Otti Berger-Stoffe”, a request which was granted by Wohnbedarf.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

| Line 26: | Line 38: | ||

In her continued efforts for recognition, Berger sought patents for some of her fabrics. In fact, she was the only weaver from the Bauhaus to apply for patents for her designs. Though she sought to patent three of her inventions, she received patents for only two - one in Germany in 1934 and the other in London in 1937.<ref name=":2" /> |

In her continued efforts for recognition, Berger sought patents for some of her fabrics. In fact, she was the only weaver from the Bauhaus to apply for patents for her designs. Though she sought to patent three of her inventions, she received patents for only two - one in Germany in 1934 and the other in London in 1937.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

== |

==Last years== |

||

Not allowed to work in Germany under Nazi rule because of her Jewish roots, Berger closed her company down in 1936.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=Jemma |first=Sophie |date=2020-01-27 |title=Bauhaus in Britain: The work of Otti Berger for Helios |url=https://warnertextilearchive.co.uk/bauhaus-in-britain-the-work-of-otti-berger-for-helios/ |access-date=2023-02-21 |website=Warner Textile Archive |language=en-GB}}</ref> She fled to London in 1937, where she was able to support herself with sporadic design contracts,<ref name=":3">{{ |

Not allowed to work in Germany under Nazi rule because of her Jewish roots, Berger closed her company down in 1936.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=Jemma |first=Sophie |date=2020-01-27 |title=Bauhaus in Britain: The work of Otti Berger for Helios |url=https://warnertextilearchive.co.uk/bauhaus-in-britain-the-work-of-otti-berger-for-helios/ |access-date=2023-02-21 |website=Warner Textile Archive |language=en-GB}}</ref> She fled to London in 1937, where she was able to support herself with sporadic design contracts,<ref name=":3">{{cite journal |last1=Halén |first1=Widar |title=The Bauhaus Weaver and Textile Designer Otti Berger (1898–1944/45): her Scandinavian connections and the tragic end of her career |journal=The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 - the Present |date=2019 |issue=43 |pages=114–149 |jstor=27113273 }}</ref> including work with Helios Ltd and Marianne Straub.<ref name=":5" /> However, her hearing impairment and language barrier made life in England difficult. In a letter to a friend, Berger penned, "The English are very reserved. I believe it will take ten years before one has a circle of friends. I am always alone and find it difficult because I do not know English and cannot hear."<ref name=":3" /> |

||

Over the course of several years, Berger's attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancé [[Ludwig Hilberseimer]] and other Bauhaus professors failed.<ref>Fischer, Linn. "Otti (Otilija Ester) Berger. 1898 – 1944." ''Aviva: Online Magazin fuer Frauen''. Berlin: 2015.</ref><ref name=":1" /> László Moholy-Nagy had offered her a place as head of weaving at the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which she would never reach. She wrote to Naum Gabo, Walter Gropius, and other friends trying to gain a teaching visa in 1937 but never acquired one.<ref name=":2" /> Due to the political state in England as war approached, Berger's distaste for England grew.<ref name=":3" /> Against the pleas of close friends, Berger returned to her homeland of Zmajevac in 1938 to help her family with her mother's poor health.<ref name=":1" /> After several years spent with family, in April 1944 Berger was deported alongside her brother, half-brother, and his wife to a detention camp in Mohács. Shortly thereafter in May 1944, they were transferred to [[Auschwitz concentration camp]] in April 1944. Only Berger's brother, Otto, survived. He speculated that Otti had been killed with German gas due to her lack of hearing.<ref name=":3" /> |

Over the course of several years, Berger's attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancé [[Ludwig Hilberseimer]] and other Bauhaus professors failed.<ref>Fischer, Linn. "Otti (Otilija Ester) Berger. 1898 – 1944." ''Aviva: Online Magazin fuer Frauen''. Berlin: 2015.</ref><ref name=":1" /> László Moholy-Nagy had offered her a place as head of weaving at the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which she would never reach. She wrote to Naum Gabo, Walter Gropius, and other friends trying to gain a teaching visa in 1937 but never acquired one.<ref name=":2" /> Due to the political state in England as war approached, Berger's distaste for England grew.<ref name=":3" /> Against the pleas of close friends, Berger returned to her homeland of Zmajevac in 1938 to help her family with her mother's poor health.<ref name=":1" /> After several years spent with family, in April 1944 Berger was deported alongside her brother, half-brother, and his wife to a detention camp in Mohács. Shortly thereafter in May 1944, they were transferred to [[Auschwitz concentration camp]] in April 1944. Only Berger's brother, Otto, survived. He speculated that Otti had been killed with German gas due to her lack of hearing.<ref name=":3" /> |

||

== |

==Impact== |

||

Otti Berger's work was influential across Europe due to various patents on her designs. She had her works published in magazines such as ''Der Konfektionar,'' the Dutch multi-lingual magazine ''International Textiles,'' the Swedish magazine ''Spektrum,'' and ''Domus'' magazine. Otti Berger partnered with Dutch weaving company De Ploeg where her designs were sold to furniture factories that produced stock for De Bijenkorf and Metz and Co department stores.<ref name=":3" /> |

Otti Berger's work was influential across Europe due to various patents on her designs. She had her works published in magazines such as ''Der Konfektionar,'' the Dutch multi-lingual magazine ''International Textiles,'' the Swedish magazine ''Spektrum,'' and ''Domus'' magazine. Otti Berger partnered with Dutch weaving company De Ploeg where her designs were sold to furniture factories that produced stock for De Bijenkorf and Metz and Co department stores.<ref name=":3" /> |

||

In |

In 1933, Berger published "Rätta stoffer pa rätt plats" ("The Right Fabrics in the Right Place") which influenced many Swedish designers to reconsider their designs for housing textiles so that they "fulfill the demands and needs of [the] time."<ref name=":3" /> |

||

Berger's works have been exhibited at museums internationally such as the [[Harvard Art Museums|Busch-Reisinger Museum]], the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]], and collected at Harvard Universities' exhibit "[https://community.harvard.edu/event/exhibition-bauhaus-and-harvard#:~:text=Harvard%20University%20played%20host%20to,department%20of%20architecture%20in%201937. The Bauhaus and Harvard]," and the [[Ludwig Hilberseimer]] collection at the [[Art Institute of Chicago]].<ref name=":3" /> |

Berger's works have been exhibited at museums internationally such as the [[Harvard Art Museums|Busch-Reisinger Museum]], the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]], and collected at Harvard Universities' exhibit "[https://community.harvard.edu/event/exhibition-bauhaus-and-harvard#:~:text=Harvard%20University%20played%20host%20to,department%20of%20architecture%20in%201937. The Bauhaus and Harvard]," and the [[Ludwig Hilberseimer]] collection at the [[Art Institute of Chicago]].<ref name=":3" /> |

||

== |

==Quote== |

||

| ⚫ | {{Blockquote|text=The handle of stuff is of primary importance. A piece of stuff must be touched and felt; it has to be held in the hands. The beauty of a stuff is above all, known by its feel. The feel of stuff in the hands can be just as beautiful an experience as colour can be to the eye or sound to the ear.|author=Otti Berger|title="Stoffe im Raum", or "Fabric for the Home"}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Behan |first1=Antonia |title=''Stoffe im Raum'' (1930) |journal=The Journal of Modern Craft |date=2 September 2021 |volume=14 |issue=3 |pages=287–289 |doi=10.1080/17496772.2021.2000705 |s2cid=244767272 }}</ref> |

||

==Gallery== |

|||

<gallery widths="150" perrow="3"> |

<gallery widths="150" perrow="3"> |

||

File:Otti Berger textile 1.jpg|Sample ( |

File:Otti Berger textile 1.jpg|Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane and cotton, 43.1 × 37 cm (17 × 14 1/2 in.), 1927-1933 |

||

File:Otti Berger textile 2.jpg|Sample ( |

File:Otti Berger textile 2.jpg|Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 27.3 × 26.1 cm (10 3/4 × 10 1/4 in.), 1927-1933 |

||

File:Otti Berger textile 3.jpg|Sample ( |

File:Otti Berger textile 3.jpg|Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 31.8 × 38 cm (12 1/2 × 15 in.), 1927-1933 |

||

File:Otti Berger textile 4.jpg|Sample ( |

File:Otti Berger textile 4.jpg|Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 26.2 × 33 cm (10 1/4 × 13 1/8 in.), 1927-1933 |

||

File:Otti Berger textile 5.jpg|Sample ( |

File:Otti Berger textile 5.jpg|Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 35.5 × 45.8 cm (14 × 18 in.), 1927-1933 |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Anni Albers]] |

* [[Anni Albers]] |

||

* [[Friedl Dicker-Brandeis]] |

* [[Friedl Dicker-Brandeis]] |

||

| Line 60: | Line 75: | ||

{{commons category|Otti Berger}} |

{{commons category|Otti Berger}} |

||

* [http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/artist/Berger,+Otti Otti Berger entry] at the [[Art Institute of Chicago]] |

* [http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/artist/Berger,+Otti Otti Berger entry] at the [[Art Institute of Chicago]] |

||

* [http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger Otti Berger entry] at [[Bauhaus]] Online |

* [http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger Otti Berger entry] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160627235744/http://bauhaus-online.de/en/atlas/personen/otti-berger |date=June 27, 2016 }} at [[Bauhaus]] Online |

||

* [http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/488834 Artwork by Otti Berger] at the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] |

* [http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/488834 Artwork by Otti Berger] at the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20150615073843/http://www.baunet-info.com/research-networking/artists-groups-topics/otti-berger/ Biography and works] at Baunet |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20150615073843/http://www.baunet-info.com/research-networking/artists-groups-topics/otti-berger/ Biography and works] at Baunet |

||

| Line 66: | Line 81: | ||

*[http://www.aviva-berlin.de/aviva/Found.php?id=1418566 Otti Berger] research and related links on ''Aviva'' |

*[http://www.aviva-berlin.de/aviva/Found.php?id=1418566 Otti Berger] research and related links on ''Aviva'' |

||

{{ |

{{Weaving}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

Latest revision as of 23:26, 5 December 2024

Otti Berger | |

|---|---|

Otti Berger (1930) | |

| Born | Otilija Ester Berger October 4, 1898 |

| Died | May 3, 1944 (aged 45) |

| Education | Bauhaus |

| Known for | Textiles weaving |

Otti Berger (Otilija Ester Berger) (4 October 1898, in present-day Zmajevac, Croatia - 3 May 1944) was a Croatian student and later teacher at the Bauhaus, where she was a textile artist and weaver. She was murdered in 1944 at Auschwitz during the Holocaust.

Early life

[edit]Otti Berger was born on 4 October 1898 in present-day Zmajevac, Croatia. At the time of Berger’s birth, Zmajevac was part of the Baranya region of Austro-Hungary and was known as Vörösmart. Berger’s Jewish family was granted unrestricted residence and freedom in religion under the rule of Emperor Franz Joseph I. Because of Vörösmart’s national transition from Austro-Hungarian to Yugoslavian in 1918, and later Croatian, Berger’s nationality was and still is often mistaken. Though a native Hungarian speaker, Berger was also fluent in German. Due to a previous illness, Berger suffered from partial hearing loss, which was said to have heightened or enhanced her sense of touch.[1]

Education

[edit]

Berger was born in Zmajevac in Austro-Hungarian Empire (present-day Croatia).[2] She completed education at the Collegiate School for Girls in Vienna before enrolling in the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, now the Academy of Fine Arts, University of Zagreb. She continued her studies in Zagreb until 1926 before attending Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany.[3] There, Berger studied under László Moholy-Nagy, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky, among others. Berger has been described as "one of the most talented students at the weaving workshop in Dessau."[4]

A core member of the experimental approach to textiles at the Bauhaus,[6] Berger experimented with methodology and materials during the course of her studies at the Bauhaus to eventually include plastic textiles intended for mass production.[7] Along with Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, Berger pushed back against the understanding of textiles as a feminine craft and utilized rhetoric used in photography and painting to describe her work.[6] During her time in Dessau, she also wrote a treatise on fabrics and the methodology of textile production, which stayed with Walter Gropius and was never published.[7]

In 1929, Berger attended classes at Praktiska Vävnadsskolan in Stockholm where she wrote a nine-page thesis about Swedish Weaving techniques called 'Schwedische Bindungslehre', which later influenced her published weaving instructing booklet, Bindungslehre.[8]

In 1931, Berger became the new head of weaving at the Bauhaus under the advisement of Stolzl, who had resigned from the position. She began to create her own curriculum, and acted as a mentor to younger Bauhaus students who carried on Bauhaus methods, including Paris-based weaver Zsuzsa Markos-Ney and Etel Fodor-Mittag, who became a hand weaver in South Africa.[7][3] It was a short-lived position, however, as she was replaced in 1932 by Lilly Reich, the partner of new Bauhaus director Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.[1]

Career

[edit]When the Bauhaus closed under German force in 1932, Berger opened her own textile design studio, "otti berger atelier für textilien," which she ran from her apartment in Berlin using looms she purchased from the school's weaving workshop.[1] There, her goal was to produce textiles for use in industry. She secured contracts with several design firms, including Wohnbedarf AG, a Swedish design company, and worked with manufacturers C.F. Baumgärtel & Sohn, Schriever and Websky, as well as Hartmann and Wiesen.[9]

Berger was interested in authoring her own work and making a name for herself as a designer of woven textiles, which is uncommon in the industrial textile production field. She went so far as to begin signing her woven works with her initials in lowercase, “o.b.” In 1932, while working on designs for Wohnbedarf AG, Berger pushed for recognition, in fear that her work would be subjected to anonymity within the large design company. She asked that her prototypes be attached to the name “Otti Berger-Stoffe”, a request which was granted by Wohnbedarf.[9]

In her continued efforts for recognition, Berger sought patents for some of her fabrics. In fact, she was the only weaver from the Bauhaus to apply for patents for her designs. Though she sought to patent three of her inventions, she received patents for only two - one in Germany in 1934 and the other in London in 1937.[9]

Last years

[edit]Not allowed to work in Germany under Nazi rule because of her Jewish roots, Berger closed her company down in 1936.[10] She fled to London in 1937, where she was able to support herself with sporadic design contracts,[8] including work with Helios Ltd and Marianne Straub.[10] However, her hearing impairment and language barrier made life in England difficult. In a letter to a friend, Berger penned, "The English are very reserved. I believe it will take ten years before one has a circle of friends. I am always alone and find it difficult because I do not know English and cannot hear."[8]

Over the course of several years, Berger's attempts to emigrate to United States to work with her fiancé Ludwig Hilberseimer and other Bauhaus professors failed.[11][3] László Moholy-Nagy had offered her a place as head of weaving at the New Bauhaus in Chicago, which she would never reach. She wrote to Naum Gabo, Walter Gropius, and other friends trying to gain a teaching visa in 1937 but never acquired one.[9] Due to the political state in England as war approached, Berger's distaste for England grew.[8] Against the pleas of close friends, Berger returned to her homeland of Zmajevac in 1938 to help her family with her mother's poor health.[3] After several years spent with family, in April 1944 Berger was deported alongside her brother, half-brother, and his wife to a detention camp in Mohács. Shortly thereafter in May 1944, they were transferred to Auschwitz concentration camp in April 1944. Only Berger's brother, Otto, survived. He speculated that Otti had been killed with German gas due to her lack of hearing.[8]

Impact

[edit]Otti Berger's work was influential across Europe due to various patents on her designs. She had her works published in magazines such as Der Konfektionar, the Dutch multi-lingual magazine International Textiles, the Swedish magazine Spektrum, and Domus magazine. Otti Berger partnered with Dutch weaving company De Ploeg where her designs were sold to furniture factories that produced stock for De Bijenkorf and Metz and Co department stores.[8]

In 1933, Berger published "Rätta stoffer pa rätt plats" ("The Right Fabrics in the Right Place") which influenced many Swedish designers to reconsider their designs for housing textiles so that they "fulfill the demands and needs of [the] time."[8]

Berger's works have been exhibited at museums internationally such as the Busch-Reisinger Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and collected at Harvard Universities' exhibit "The Bauhaus and Harvard," and the Ludwig Hilberseimer collection at the Art Institute of Chicago.[8]

Quote

[edit]The handle of stuff is of primary importance. A piece of stuff must be touched and felt; it has to be held in the hands. The beauty of a stuff is above all, known by its feel. The feel of stuff in the hands can be just as beautiful an experience as colour can be to the eye or sound to the ear.

— Otti Berger, "Stoffe im Raum", or "Fabric for the Home"

Gallery

[edit]-

Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane and cotton, 43.1 × 37 cm (17 × 14 1/2 in.), 1927-1933

-

Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 27.3 × 26.1 cm (10 3/4 × 10 1/4 in.), 1927-1933

-

Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 31.8 × 38 cm (12 1/2 × 15 in.), 1927-1933

-

Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 26.2 × 33 cm (10 1/4 × 13 1/8 in.), 1927-1933

-

Sample (Upholstery Fabric) by Otti Berger, cellophane, 35.5 × 45.8 cm (14 × 18 in.), 1927-1933

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Otto, Elizabeth (2019). Bauhaus women : a global perspective. Patrick Rössler. London, UK. ISBN 978-1-912217-96-0. OCLC 1084302497.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ "Otti Berger – Croatian Artist from the Bauhaus Textile Workshop | Bauhaus Online". bauhaus-online.de. Archived from the original on July 7, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Otti Berger | Bauhaus Online". bauhaus-online.de. Archived from the original on June 27, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Weibel, Peter. Beyond Art: A Third Culture. A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 2005. p. 76

- ^ "Otti Berger. Book. The Met". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Smith, T’ai (2014). Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-4529-4323-7. Project MUSE book 35700.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Weibel, Peter. Beyond Art: A Third Culture. A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary. Vienna: Springer-Verlag, 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Halén, Widar (2019). "The Bauhaus Weaver and Textile Designer Otti Berger (1898–1944/45): her Scandinavian connections and the tragic end of her career". The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 - the Present (43): 114–149. JSTOR 27113273.

- ^ a b c d Smith, T'ai (June 2008). "Anonymous Textiles, Patented Domains: The Invention (and Death) of an Author". Art Journal. 67 (2): 54–73. doi:10.1080/00043249.2008.10791304. S2CID 191345039.

- ^ a b Jemma, Sophie (January 27, 2020). "Bauhaus in Britain: The work of Otti Berger for Helios". Warner Textile Archive. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Fischer, Linn. "Otti (Otilija Ester) Berger. 1898 – 1944." Aviva: Online Magazin fuer Frauen. Berlin: 2015.

- ^ Behan, Antonia (September 2, 2021). "Stoffe im Raum (1930)". The Journal of Modern Craft. 14 (3): 287–289. doi:10.1080/17496772.2021.2000705. S2CID 244767272.

External links

[edit]- Otti Berger entry at the Art Institute of Chicago

- Otti Berger entry Archived June 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine at Bauhaus Online

- Artwork by Otti Berger at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Biography and works at Baunet

- Photograph "Party at Otti Berger's" at the Getty Center

- Otti Berger research and related links on Aviva

- 1898 births

- 1944 deaths

- People from Osijek-Baranja County

- Bauhaus alumni

- Academic staff of the Bauhaus

- Textile artists

- German weavers

- Croatian people who died in Auschwitz concentration camp

- Women textile artists

- Jewish artists

- Croatian Jews who died in the Holocaust

- Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to the United Kingdom

- Croatian civilians killed in World War II