Chʼortiʼ language: Difference between revisions

m replaced: possesives → possessives, typo(s) fixed: doesn’t → doesn't, it’s → it's, ’s → 's |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Mayan language spoken in Central America}} |

{{Short description|Mayan language spoken in Central America}} |

||

{{Multiple issues| |

|||

{{more footnotes needed|date=February 2011}} |

|||

{{cleanup|date=April 2017|reason=article is generally disorganised and lacking focus}} |

|||

{{section move from|date=May 2019}} |

|||

{{Cleanup bare URLs|date=August 2022}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{POV|date=October 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox language |

{{Infobox language |

||

|name=Chʼortiʼ |

| name = Chʼortiʼ |

||

|nativename= |

| nativename = |

||

|states=[[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]], [[El Salvador]] |

| states = [[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]], [[El Salvador]] |

||

|region=[[Copán]] |

| region = [[Copán]] |

||

|ethnicity=[[Chʼortiʼ people|Chʼortiʼ]] |

| ethnicity = [[Chʼortiʼ people|Chʼortiʼ]] |

||

|speakers=30,000 |

| speakers = 30,000 |

||

|date=2000 |

| date = 2000 |

||

|ref=e18 |

| ref = e18 |

||

|familycolor= |

| familycolor = Mayan |

||

|fam1=[[Mayan languages|Mayan]] |

| fam1 = [[Mayan languages|Mayan]] |

||

|fam2= |

| fam2 = Cholan–Tzeltalan |

||

|fam3=Cholan |

| fam3 = [[Ch'olan languages|Cholan]] |

||

|fam4= |

| fam4 = |

||

|ancestor=[[Classic Maya language|Classic Maya]] |

| ancestor = [[Classic Maya language|Classic Maya]] |

||

|iso3=caa |

| iso3 = caa |

||

|glotto=chor1273 |

| glotto = chor1273 |

||

|glottorefname=Chorti |

| glottorefname = Chorti |

||

|notice=IPA |

| notice = IPA |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Chʼortiʼ language''' (sometimes also ''Chorti'') is a [[Mayan language]], spoken by the [[Maya peoples|indigenous Maya]] people who are also known as the [[Chʼortiʼ people|Chʼortiʼ]] or Chʼortiʼ Maya. Chʼortiʼ is a direct descendant of the [[Classic Maya language]] in which many of the [[pre-Columbian]] inscriptions using the [[Maya script]] were written.<ref name="Houston, S 2000" /> Chʼortiʼ is the modern version of the ancient Mayan language Chʼolan (which was actively used and most popular between the years of A.D 250 and 850).<ref name="Houston, S 2000">Houston, S, J Robertson, and D Stuart. "The language of Classic Maya inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41.3 (2000): 321–356. Print.</ref> |

The '''Chʼortiʼ language''' (sometimes also ''Chorti'') is a [[Mayan language]], spoken by the [[Maya peoples|indigenous Maya]] people who are also known as the [[Chʼortiʼ people|Chʼortiʼ]] or Chʼortiʼ Maya. Chʼortiʼ is a direct descendant of the [[Classic Maya language]] in which many of the [[pre-Columbian]] inscriptions using the [[Maya script]] were written.<ref name="Houston, S 2000" /> Chʼortiʼ is the modern version of the ancient Mayan language Chʼolan (which was actively used and most popular between the years of A.D 250 and 850).<ref name="Houston, S 2000">Houston, S, J Robertson, and D Stuart. "The language of Classic Maya inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41.3 (2000): 321–356. Print.</ref> |

||

==Classification== |

|||

==Relationship to other Mayan languages== |

|||

Chʼortiʼ can be called a living "[[Rosetta Stone]]" of Mayan languages. |

Chʼortiʼ can be called a living "[[Rosetta Stone]]" of Mayan languages. Chʼortiʼ is an important tool for interpreting the contents of Maya glyphic writings, some of which are not yet fully understood. For several years, many linguists and anthropologists expected to grasp the Chʼortiʼ culture and language by studying its words and expressions.<ref>{{Cite web | last=Keys | first=David | title='Lost' Sacred Language of the Maya Is Rediscovered | website=mayanmajix.com | date=2003-12-07 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031219112500/http://mayanmajix.com/art439a.html | archive-date=2003-12-19 | url=http://mayanmajix.com/art439a.html}}</ref> Chʼortiʼ is spoken mainly in and around [[Jocotán]] and [[Camotán]], [[Chiquimula]] department, [[Guatemala]], as well as in adjacent areas of parts of western [[Honduras]] near the [[Copán|Copán Ruins]].<ref name="hdl.handle.net">{{Cite web | last=Hull | first=Kerry M. | year=2003 | title=Verbal art and performance in Chʼortiʼ and Maya hieroglyphic writing | publisher=The University of Texas at Austin | url= https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/items/2f24e188-4375-4048-9fcf-569d66d979d8/full}}</ref> Because the Classic Mayan language was ancestral to the modern Chʼorti, it can be used to decipher the ancient language.<ref name="Houston, S 2000"/> Researchers realized that the ancient language was based more on phonetics than previously thought.<ref name="Houston, S 2000"/> |

||

[[File:Mayan Language Map.png|thumb|A map showing the present-day locations of the Mayan Languages. The colors of the language names |

[[File:Mayan Language Map.png|thumb|A map showing the present-day locations of the Mayan Languages. The colors of the language names show closely-related groups. The size of the name shows the relative number of speakers.]] |

||

The name |

The name Chʼortiʼ (with unglottalized <ch>) means 'language of the corn farmers', a reference to the traditional agricultural activity of Chʼortiʼ families. It is one of the three modern descendants of the Chʼolan language, which constitute a sub-group of [[Mayan languages]]. The other two are [[Chontal Maya language|Chontal]] and [[Chʼol language|Chʼol]].<ref>{{Cite web | last1=Mathews | first1=Peter | last2=Bíró | first2=Péter | title=Maya Hieroglyphs and Mayan Languages | url=http://research.famsi.org/mdp/mdp_mayahiero.html | website=research.famsi.org}}</ref> These three descendants are still spoken today. Chʼortiʼ and Chʼolti are two sub-branches belonging to Eastern Chʼolan; Chʼolti is, however, already extinct. |

||

There are some debates among |

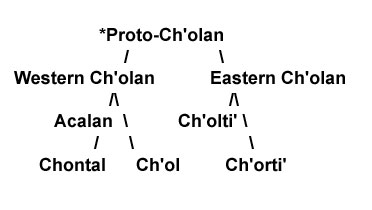

There are some debates among scholars about how Chʼolan should be classified. John Robertson considered the direct ancestor of colonial Chʼoltiʼ to be the language of the [[Mayan script]] (also known as Mayan Glyphs). The language of the Mayan Glyphs is described as 'Classic Chʼoltiʼan' by John Robertson, David Stuart, and Stephen Houston. The language of the Mayan script is thus the ancestor of Chʼortiʼ. The relationship is shown in the chart below.<ref name="hdl.handle.net"/> |

||

[[File:The Ch'olan sub-group of Mayan languages.jpg|The Chʼolan sub-group of Mayan languages]] |

[[File:The Ch'olan sub-group of Mayan languages.jpg|The Chʼolan sub-group of Mayan languages]] |

||

== |

==Endangerment== |

||

The Chʼortiʼ people are descendants of the people who lived in and around [[Copán]], one of the cultural capitals |

The Chʼortiʼ people are descendants of the people who lived in and around [[Copán]], one of the cultural capitals of the ancient Maya area. This covers parts of modern-day Honduras and Guatemala. Chʼorti is considered an endangered language as well as an endangered culture. |

||

===Geographic location |

===Geographic location=== |

||

[[File:Distribution-myn2.png|thumbnail]] |

[[File:Distribution-myn2.png|thumbnail]] |

||

This region is the only region in the world that Chʼorti speakers can be found. Although the area is completely shaded in, the majority of speakers reside in Guatemala, while the rest are sparsely distributed throughout the rest of the area.<ref>• McAnany, Patricia, and Shoshaunna Parks. "Casualties of Heritage Distancing Children, Chʼortiʼ Indigeneity, and the Copan Archaeoscape." Current Anthropology 53.1 (2012): 80–107. Print.</ref> |

This region is the only region in the world that Chʼorti speakers can be found. Although the area is completely shaded in, the majority of speakers reside in Guatemala, while the rest are sparsely distributed throughout the rest of the area.<ref>• McAnany, Patricia, and Shoshaunna Parks. "Casualties of Heritage Distancing Children, Chʼortiʼ Indigeneity, and the Copan Archaeoscape." Current Anthropology 53.1 (2012): 80–107. Print.</ref> |

||

===Honduras=== |

===Honduras=== |

||

The government of Honduras has been trying to promote a uniform national language of Spanish, and therefore discourages the use and teaching of native languages such as Chʼorti. The Chʼortiʼ people in Honduras face homogenization and have to assimilate to their surroundings. The government has been clashing with the Chʼorti people over land disputes from the 1800s, which puts the people (and thus the language) at risk. In 1997, 2 prominent Chʼorti leaders were assassinated. This assassination is just one example of many cases where Chʼorti advocates have been harmed or killed. Every one of these killings reduces the number of Chʼorti speakers. As of right now, there are only 10 remaining native speakers in Honduras.<ref name="minorityrights.org"> |

The government of Honduras has been trying to promote a uniform national language of Spanish, and therefore discourages the use and teaching of native languages such as Chʼorti. The Chʼortiʼ people in Honduras face homogenization and have to assimilate to their surroundings. The government has been clashing with the Chʼorti people over land disputes from the 1800s, which puts the people (and thus the language) at risk. In 1997, 2 prominent Chʼorti leaders were assassinated. This assassination is just one example of many cases where Chʼorti advocates have been harmed or killed. Every one of these killings reduces the number of Chʼorti speakers. As of right now, there are only 10 remaining native speakers in Honduras.<ref name="minorityrights.org">{{cite web |url=http://www.minorityrights.org/2572/honduras/lenca-miskitu-tawahka-pech-maya-chortis-and-xicaque.html |title=Minority Rights Group International : Honduras : Lenca, Miskitu, Tawahka, Pech, Maya, Chortis and Xicaque |access-date=2013-10-25 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029193324/http://www.minorityrights.org/2572/honduras/lenca-miskitu-tawahka-pech-maya-chortis-and-xicaque.html |archive-date=2013-10-29 | publisher=World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples}}</ref> |

||

===Guatemala=== |

===Guatemala=== |

||

| Line 55: | Line 50: | ||

===Ethnonyms: Cholotí, Chorté, Chortí=== |

===Ethnonyms: Cholotí, Chorté, Chortí=== |

||

The majority of Chʼortiʼ live in the Chiquimula Department of Guatemala, approximately 52,000. The remaining 4,000 live in Copán, Honduras. The Kʼicheʼ Maya however, dominated the Chʼortiʼ dating back to the early fifteenth century. Warfare as well as disease devastated much of the Chʼortiʼ during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of their land was lost to the Guatemalan government in the nineteenth century as well. More recently, 25 percent of the Guatemalan Chʼortiʼ went to the United States during the 1980s to escape political persecution.<ref>Chenier |

The majority of Chʼortiʼ live in the Chiquimula Department of Guatemala, approximately 52,000. The remaining 4,000 live in Copán, Honduras. The Kʼicheʼ Maya however, dominated the Chʼortiʼ dating back to the early fifteenth century. Warfare as well as disease devastated much of the Chʼortiʼ during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of their land was lost to the Guatemalan government in the nineteenth century as well. More recently, 25 percent of the Guatemalan Chʼortiʼ went to the United States during the 1980s to escape political persecution.<ref>{{Cite web | last1=Chenier | first1=Jacqueline | first2=Steve | last2=Sherwood | title=Copan: Collaboration for Identity, Equity and Sustainability (Honduras) | website=srdis.ciesin.columbia.edu | publisher=Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) | date=2013-10-27 | url=http://srdis.ciesin.columbia.edu/cases/Honduras-Paper.html | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070614002729/http://srdis.ciesin.columbia.edu/cases/Honduras-Paper.html | archive-date=2007-06-14}}</ref> |

||

== Phonology and orthography == |

== Phonology and orthography == |

||

The Chʼortiʼ have their own standard way of writing their language. However, inaccurate ways to represent phonemes led to some variation among recent publications.<ref name="famsi.org">Hull |

The Chʼortiʼ have their own standard way of writing their language. However, inaccurate ways to represent phonemes led to some variation among recent publications.<ref name="famsi.org">{{Cite web | last=Hull | first=Kerry | year=2005 | title=A Dictionary of Chʼortiʼ Maya, Guatemala | website=FAMSI.org | url=http://www.famsi.org/reports/03031/03031Hull01.pdf}}</ref><ref name=":0" /> |

||

=== Consonants === |

=== Consonants === |

||

| Line 77: | Line 72: | ||

| |

| |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! rowspan=" |

! rowspan="3" |[[Plosive]] |

||

! <small>[[voicelessness|voiceless]]</small> |

! <small>[[voicelessness|voiceless]]</small> |

||

| {{IPA link|p}} {{grapheme|p}} |

| {{IPA link|p}} {{grapheme|p}} |

||

| Line 83: | Line 78: | ||

| |

| |

||

| {{IPA link|k}} {{grapheme|k}} |

| {{IPA link|k}} {{grapheme|k}} |

||

| rowspan="2" |{{IPA link|ʔ}} {{grapheme|ʼ}} |

| rowspan="2" | {{IPA link|ʔ}} {{grapheme|ʼ}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!<small>[[ |

!<small>[[Glottalic consonant|glottalic]]</small> |

||

| {{IPA link|ɓ}} {{grapheme|bʼ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|tʼ}} {{grapheme|tʼ}} |

| {{IPA link|tʼ}} {{grapheme|tʼ}} |

||

| |

| |

||

| {{IPA link|kʼ}} {{grapheme|kʼ}} |

| {{IPA link|kʼ}} {{grapheme|kʼ}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

!<small>[[Voice (phonetics)|voiced]]</small> |

!<small>[[Voice (phonetics)|voiced]]</small>{{efn|/b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ usually only appear in [[Spanish language|Spanish]] loan words.}} |

||

| {{IPA link|b}} {{grapheme|b}} |

| ({{IPA link|b}} {{grapheme|b}}) |

||

| {{IPA link|d}} {{grapheme|d}} |

| ({{IPA link|d}} {{grapheme|d}}) |

||

| |

|||

| {{IPA link|ɡ}} {{grapheme|g}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|||

!<small>[[Implosive consonant|implosive]]</small> |

|||

|{{IPA link|ɓ}} {{grapheme|bʼ}} |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

| |

| |

||

| ({{IPA link|ɡ}} {{grapheme|g}}) |

|||

| |

| |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 124: | Line 112: | ||

| {{IPA link|s}} {{grapheme|s}} |

| {{IPA link|s}} {{grapheme|s}} |

||

| {{IPA link|ʃ}} {{grapheme|x}} |

| {{IPA link|ʃ}} {{grapheme|x}} |

||

| {{IPA link|x}} {{grapheme|j}}{{efn|name=jh|{{grapheme|j}} has two pronunciations, as either a voiceless velar fricative {{IPAblink|x}} or a voiceless glottal fricative {{IPAblink|h}}. Classic Mayan differentiated between the two. This differentiation can be seen in some Chʼortiʼ literature, such as with the texts by Wisdom.}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|x}} {{grapheme|j}} |

|||

| {{IPA link|h}} {{grapheme|j}}{{efn|name=jh}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! colspan="2" |[[Trill consonant|Trill]] |

! colspan="2" |[[Trill consonant|Trill]] |

||

| Line 141: | Line 129: | ||

| |

| |

||

|} |

|} |

||

{{notelist}} |

|||

The consonants of Chʼortiʼ include glottal stop [ʼ], b, bʼ, ch, chʼ, d, g, j, k, kʼ, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, tʼ, tz, tzʼ, w, x, y. |

The consonants of Chʼortiʼ include glottal stop [ʼ], b, bʼ, ch, chʼ, d, g, j, k, kʼ, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, tʼ, tz, tzʼ, w, x, y. |

||

The {{grapheme|w}} and {{grapheme|y}} are semivowels. |

|||

Instances of both /b/ and /d/ usually only appear in [[Spanish language|Spanish]] loan words. The j has two pronunciations, as either a voiceless velar fricative [x] or a voiceless glottal fricative [h]. Classic Mayan differentiated between the [x] and the [h]. This differentiation can be seen in some Ch’orti’ literature, such as with the texts by Wisdom. The <w> and <y> are semivowels. |

|||

The ordering of terms would be that the consonants follows after the non glottal versions. Besides, words with rearticulated root vowels follow after their corresponding short vowels. |

|||

Therefore, the order of presentation will be as follows: a, aʼ, b, bʼ, ch, chʼ, d, e, eʼ, g, i, iʼ, j, k, kʼ, l, m, n, o, oʼ, p, r, s, t, tʼ, tz, tzʼ, u, uʼ, w, x, y. |

|||

=== Vowels === |

=== Vowels === |

||

| Line 173: | Line 158: | ||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+ |

|+ |

||

!Characters we use |

!Characters we{{Who|date=October 2024}} use |

||

!Sometimes also used |

!Sometimes also used |

||

!IPA symbol |

!IPA symbol |

||

! |

!Chʼortiʼ pronunciation |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|aa |

|aa |

||

|ā, |

|ā, aꞏ, a꞉ |

||

|a |

|a |

||

|Like regular a but held longer |

|Like regular a but held longer |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|ee |

|ee |

||

|ē, |

|ē, eꞏ, e꞉ |

||

|e |

|e |

||

|Like e only held longer |

|Like e only held longer |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|ii |

|ii |

||

|ī, |

|ī, iꞏ, i꞉ |

||

|i |

|i |

||

|Like i only held longer |

|Like i only held longer |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|oo |

|oo |

||

|ō, |

|ō, oꞏ, o꞉ |

||

|o |

|o |

||

|Like o only held longer |

|Like o only held longer |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|uu |

|uu |

||

|ū, |

|ū, uꞏ, u꞉ |

||

|u |

|u |

||

|Like u only held longer |

|Like u only held longer |

||

|} |

|} |

||

When two vowels are put together in |

When two vowels are put together in Chʼortiʼ the second vowel always takes precedence and then is always followed by a glottal stop. Chʼortiʼ doesn't have any long vowels. According to historians, long vowels occur in Classical Mayan, but have been lost in modern Chʼortiʼ. |

||

In |

In Chʼortiʼ language, aa or a꞉ is used as aʼ or Aʼ, we can see this pattern with all vowel clusters including eʼ, Iʼ, oʼ and uʼ. |

||

Some examples of words with vowel clusters |

Some examples of words with vowel clusters are꞉ |

||

* |

* Jaʼx [xaʔʃ] = Her, ella |

||

* |

* Weʼr [weʔr] = meat, carne |

||

* |

* Bʼiʼx [pʼiʔʃ] = seed, semilla |

||

* |

* Tunoʼron [tunoʔɾon] = everyone, todos |

||

* |

*Kuʼm [kuʔm] = egg, huevo <ref>{{Cite web|title=Chorti Maya Pronunciation Guide, Alphabet and Phonology|url=http://www.native-languages.org/chorti_guide.htm|access-date=2020-12-17|website=www.native-languages.org}}</ref> |

||

== Syntax == |

|||

The aspectual system of Chʼortiʼ language changed to a tripartite pronominal system which comes with different morphemes used for the subject of transitive verbs, the object of transitive verbs and the subject of intransitive completive verbs, and a third set of pronouns only used for the subject of incompletive intransitive verbs.<ref>Law |

The aspectual system of Chʼortiʼ language changed to a tripartite pronominal system which comes with different morphemes used for the subject of transitive verbs, the object of transitive verbs and the subject of intransitive completive verbs, and a third set of pronouns only used for the subject of incompletive intransitive verbs.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1=Law | first1=Danny | first2=John |last2=Robertson | first3=Stephen | last3=Houston | title=Split Ergativity In The History Of The Chʼolan Branch Of The Mayan Language Family | publisher=University of Texas at Austin | journal=International Journal of American Linguistics | volume=72 | number=4 | year=2006 | pages=415–450 | url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/513056 | doi=10.1086/513056}}</ref> |

||

Chʼortiʼ tripartite pronominal system (data from Hull 2005) |

Chʼortiʼ tripartite pronominal system (data from Hull 2005) |

||

'''Transitive''' |

|||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|top='''Transitive''' |

|||

|e sitzʼ u-buyi-Ø e siʼ |

|e sitzʼ u-buyi-Ø e siʼ |

||

|def boy A-3-chop-B-3 def wood |

|def boy A-3-chop-B-3 def wood |

||

|'The boy chops the wood (into tiny pieces)'}} |

|'The boy chops the wood (into tiny pieces)'}} |

||

'''Intransitive completive''' |

|||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|top='''Intransitive completive''' |

|||

|intzaj lokʼoy-Ø e peʼych |

|intzaj lokʼoy-Ø e peʼych |

||

|sweet go.out-B-3 def tomato |

|sweet go.out-B-3 def tomato |

||

|'The tomato turned out delicious'}} |

|'The tomato turned out delicious'}} |

||

'''Intransitive incompletive''' |

|||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|top='''Intransitive incompletive''' |

|||

|e kʼin a-lokʼoy ta ixner kʼin |

|e kʼin a-lokʼoy ta ixner kʼin |

||

|def sun C-1-go.out prep going sun |

|def sun C-1-go.out prep going sun |

||

|'The sun sets in the west'}} |

|'The sun sets in the west'}} |

||

===Basic word order=== |

|||

In the Chʼortiʼ language and other Mayan sentences it always starts with verbs but also there are agents or patients added and in which they are commonly represented by the acronym VOS, meaning [[verb-object-subject]]. The following rules apply VSO, SVO, SOV, OVS, OSV.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|last=Pérez|first=Lauro|date=2004–2008|title=GRAMÁTICA PEDAGÓGICA Chʼortiʼ.|url=https://www.almg.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GRAMATICA-PEDAGOGICA..pdf?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=9aefae3b50c0990fb52169ce7595c0c596ef85dd-1607327367-0-AdVpEkLNKohiKs2VsdRy-r6wdNidSzhhVWOZ3gtz-3Bd8uJvdMnMYMA_W7jNxiGV4kFH1j0RvPF4W51xaSMFwCBKM2oBIuzEB5qq4E0vxFALuO1lKx88YExj2pqDjtDRpuQDNVFsfOF-yrf0l6Wwq49C0D4bxFMYJh1Otw2v2oIwtoJ0Qa3SXskENhDtkzVb42PW7hGQ4v3t75nMtS8UhBBOANgkzNrV6oSchVhWBk8uNWRAMHky9yVLoV0TDmznWgU0Td-vhBopba4zAGjS1wTecRBMFRFCza9kSM-PFWESw5QYfh1gTDYTTlZrMc81OB0EEDcL0lW9m0xn43492knjhpUKw3WqbF5kX4qw0mR2y450LZLCzoYVnejgml8pOw|access-date=November 17, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

In most of the Chʼortiʼ language there are phrases surrounding transitive verbs and they are order subject first (first-most) and it's followed by the verb then the object (SVO).<ref>{{Cite web|last=Dugan|first=James|date=May 20, 2013|title=The grammar of Chʼortiʼ Maya Folktales|url=https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A27759/datastream/PDF/view}}</ref> |

|||

In the Ch'orti language and other Mayan sentences it always starts with verbs but also there are agents or patients added and in which they are commonly represented by the acronym VOS, meaning [[verb-object-subject]]. The following rules apply VSO, SVO, SOV,OVS, OSV.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|last=Pérez|first=Lauro|date=2004–2008|title=GRAMÁTICA PEDAGÓGICA CH'ORTI.|url=https://www.almg.org.gt/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/GRAMATICA-PEDAGOGICA..pdf?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=9aefae3b50c0990fb52169ce7595c0c596ef85dd-1607327367-0-AdVpEkLNKohiKs2VsdRy-r6wdNidSzhhVWOZ3gtz-3Bd8uJvdMnMYMA_W7jNxiGV4kFH1j0RvPF4W51xaSMFwCBKM2oBIuzEB5qq4E0vxFALuO1lKx88YExj2pqDjtDRpuQDNVFsfOF-yrf0l6Wwq49C0D4bxFMYJh1Otw2v2oIwtoJ0Qa3SXskENhDtkzVb42PW7hGQ4v3t75nMtS8UhBBOANgkzNrV6oSchVhWBk8uNWRAMHky9yVLoV0TDmznWgU0Td-vhBopba4zAGjS1wTecRBMFRFCza9kSM-PFWESw5QYfh1gTDYTTlZrMc81OB0EEDcL0lW9m0xn43492knjhpUKw3WqbF5kX4qw0mR2y450LZLCzoYVnejgml8pOw|access-date=November 17, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

In most of the Ch’orti' language there are phrases surrounding transitive verbs and they are order subject first (first-most) and it's followed by the verb then the object (SVO).<ref>{{Cite web|last=Dugan|first=James|date=May 20, 2013|title=The grammar of Ch'orti Maya Folktales|url=https://digitallibrary.tulane.edu/islandora/object/tulane%3A27759/datastream/PDF/view}}</ref> |

|||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

| Line 251: | Line 235: | ||

|"Grandma sells vegetables."<ref name=":1" />}} |

|"Grandma sells vegetables."<ref name=":1" />}} |

||

===Adjectives with attributive function=== |

|||

The adjective works together with the nouns as a modifier formed with a noun phrase that plays some syntactic role, object etc.<ref name=":1" /> |

The adjective works together with the nouns as a modifier formed with a noun phrase that plays some syntactic role, object etc.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

| Line 258: | Line 241: | ||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|{E bʼikʼit} yurwobʼ chamobʼ |

|||

|{E b’ik’it} yurwob’ chamob’ |

|||

|adjective noun verb |

|adjective noun verb |

||

|{The little} chicks died |

|{The little} chicks died |

||

| Line 269: | Line 252: | ||

|}} |

|}} |

||

Chʼortiʼ has many other different forms, in the following sentence the words that appear to be bold is a preposition and underline one is a relational noun.<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

| Line 276: | Line 259: | ||

|"The horse passed in front of the children"}} |

|"The horse passed in front of the children"}} |

||

==Morphology== |

|||

==Vocabulary Examples== |

|||

The following list contains examples of common words in the Chʼortiʼ language: |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ Common Words |

|||

|- |

|||

! English!! Ch'orti' !! English !! Ch'orti' |

|||

|- |

|||

| big || nixi’ || fire || k’ajk’ |

|||

|- |

|||

| bird || mut || here || tara |

|||

|- |

|||

| cold || insis || what || tuk’a |

|||

|- |

|||

| dog || tx'i' || husband || noxib’ |

|||

|- |

|||

| day || k’in || man|| winik' |

|||

|- |

|||

| beverage || uch’e || moon || uj |

|||

|- |

|||

| earth || rum || mountain || witzir |

|||

|} |

|||

According to "A Dictionary of Ch'orti' Maya, Guatemala" by Kerry Hull, some words may be used as nouns (as shown above) or can double as a verb as well. For example "Witzir" can mean mountain as a noun, or 'to go uphill' as a verb. |

|||

<ref name="famsi.org"/> |

|||

== Morphology == |

|||

=== Verb inflection === |

=== Verb inflection === |

||

{|class="wikitable" |

{|class="wikitable" |

||

|+ Verb Inflections in |

|+ Verb Inflections in Chʼortiʼ<ref name="Inflection">Quizar, Robin. 1994. "Motion Verbs in Chʼortiʼ." Función 15–16. 211–229.</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! colspan="2" | |

|||

! !! Ergative (Set A) !! Absolutive (Set B) !! Subjective (Set C) |

|||

! Ergative<br />(Set A) |

|||

! Absolutive<br />(Set B) |

|||

! Subjective<br />(Set C) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! rowspan="2" | 1st<br />person |

|||

| 1S || in-/ni- || -en || in- |

|||

! {{small|singular}} |

|||

| in-/ni- |

|||

| -en |

|||

| in- |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! {{small|plural}} |

|||

| 2S || a- || -et || i- |

|||

| ka- |

|||

| -on |

|||

| ka- |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! rowspan="2" | 2nd<br />person |

|||

| 3S || u- || -Ø || a- |

|||

! {{small|singular}} |

|||

| a- |

|||

| -et |

|||

| i- |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! {{small|plural}} |

|||

| 1P || ka- || -on || ka- |

|||

| i- |

|||

| -ox |

|||

| ix- |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! rowspan="2" | 3rd<br />person |

|||

| 2P || i- || -ox || ix- |

|||

! {{small|singular}} |

|||

| u- |

|||

| -Ø |

|||

| a- |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! {{small|plural}} |

|||

| 3P || u-...-ob' || -ob' || a'...-ob' |

|||

| u-...-obʼ |

|||

| -obʼ |

|||

| aʼ...-obʼ |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

| Line 329: | Line 309: | ||

|+ Verb Inflection Examples |

|+ Verb Inflection Examples |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! Uninflected Verb |

! Uninflected Verb |

||

! Inflected Verb |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{interlinear|ixin|"to go"}} |

|||

| ''ixin'' || "to go" || ''ixinob’'' || ’go’-A3-PL || "they went" |

|||

| {{interlinear|ixinobʼ|go-A3-PL|"they went"}} |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{interlinear|ira|“to see”}} |

|||

| ''ira'' || “to see” || ''uwira'' || E3-’see’-A3 || “he sees it” |

|||

| {{interlinear|uwira|E3-see-A3|“he sees it”}} |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| {{interlinear|kojko|“to guard”}} |

|||

| ''kojko'' || “to guard” || ''ukojkob’'' || E3-’guard'-A3-PL || “they guard over it” |

|||

| {{interlinear|ukojkobʼ|E3-guard-A3-PL|“they guard over it”}} |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{interlinear|ixin|“to go”}} |

||

| {{interlinear|aʼxin|S3-go|“he goes”}} |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

<ref name="famsi.org"/> |

<ref name="famsi.org"/> |

||

==== Possessions ==== |

==== Possessions ==== |

||

Tak is plural for women and |

Tak is plural for women and childrenʼ |

||

* |

* ijchʼok-tak "little girls" |

||

* max-tak "children, young ones, family" (max does not occur without -tak) |

* max-tak "children, young ones, family" (max does not occur without -tak) |

||

* ixik-tak "women" |

* ixik-tak "women" |

||

These are the only instances encountered. It is worthy of notice that |

These are the only instances encountered. It is worthy of notice that ixkaʼr "wife", chʼurkabʼ "baby" and ar "offspring" take -ob'. |

||

obʼ is a general plural. The suffix can be found in nouns, verbs, adjectives, and participials. |

|||

Examples on possessives: |

Examples on possessives: |

||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|top= e |

|top= e mutobʼ war ubʼaxyobʼ nijinaj |

||

|e mut- |

|e mut-obʼ war u-bʼax-i-obʼ ni-jinaj |

||

|DEF.ART bird-3.PL PROG {3A-pull up-THEM-3.PL} {1A.SG-maize plant} |

|DEF.ART bird-3.PL PROG {3A-pull up-THEM-3.PL} {1A.SG-maize plant} |

||

|The birds are pulling my maize plant.}} |

|The birds are pulling my maize plant.}} |

||

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

{{interlinear|indent=3 |

||

|top= |

|top= Yarobʼ bʼikʼit ruch |

||

|Yar- |

|Yar-obʼ bʼikʼit ruch |

||

|small-3.PL {small variety of} {gourd container} |

|small-3.PL {small variety of} {gourd container} |

||

|And then come two little gourds,... |

|And then come two little gourds,... (f330040)}} |

||

<ref>{{Cite book|last=Wichmann|first=Søren|title=A |

<ref>{{Cite book|last=Wichmann|first=Søren|title=A CHʼORTIʼ MORPHOLOGICAL SKETCH|year=1999|pages=153}}</ref> |

||

== |

== Vocabulary == |

||

The following list contains examples of common words in the Chʼortiʼ language: |

|||

There are currently multiple organizations and projects that are currently working on the revitalization, documentation, and education of the Ch'orti' language. |

|||

===The Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín (PLFM)=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

The PLFM was founded in 1969. When the foundation was opened the two main purposes of the organization were to teach Spanish Language with native Spanish speakers from Guatemala as well as to teach, investigate, and preserve the Mayan Languages spoken around Guatemala. |

|||

|+ Common Words |

|||

|- |

|||

“The program... has published dictionaries, grammars, and other pedagogical materials on many Mayan languages. The organization sustains itself by offering Spanish-language classes to foreigners and applying the proceeds to their trainings and publications” |

|||

! English!! Chʼortiʼ !! English !! Chʼortiʼ |

|||

|- |

|||

The PLFM hosts a variety of projects regarding the preservation of Mayan languages, such as Ch’orti’, including cooperation with: Academy of Mayan Languages of Guatemala -ALMG-, the Indigenous Municipality of Sololá, the Ancient Maya organization for the Mayas -MAM- and liaison with brothers of the Mayan Linguistic Communities of the Mesoamerican area, the University of Tulane USA, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee USA, the Tojolab'al Language Research Center, Chiapas – Mexico, Intercultural University of Chiapas – Mexico. UNICH.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://spanishschoolplfm.com/about-us/|title = About Us}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://stonecenter.tulane.edu/pages/detail/320/Mayan-Language-Institute-in-Guatemala |title=Mayan Language Institute in Guatemala // Roger Thayer Stone Center for Latin American Studies at Tulane University |access-date=2022-02-14 |archive-date=2021-05-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515090858/https://stonecenter.tulane.edu/pages/detail/320/Mayan-Language-Institute-in-Guatemala |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

| big || nixiʼ || fire || kʼajkʼ |

|||

|- |

|||

===Academia des Lenguas Mayas De Guatemala (ALMG)=== |

|||

| bird || mut || here || tara |

|||

The [[Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala]] was founded in 1990 by a group of Guatemalan professionals interested in the research, development and promotion of the indigenous languages existing in the country. The academy is currently considered by some to be "the highest governing body for the promotion and development of Mayan languages in the country". The ALMG is an organization of the State of Guatemala that regulates the use, writing and promotion of Mayan languages. |

|||

|- |

|||

| cold || insis || what || tukʼa |

|||

The ALMG website provides a variety of information and resources regarding Ch’orti’, as well as many other Mayan languages. For Ch’orti, there are historical as well as pedagogical documents available, all of which are in a mixture of Ch’orti’ and Spanish.<ref>https://www.almg.org.gt/portfolio-item/c-l-chorti</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

| dog || txʼiʼ || husband || noxibʼ |

|||

===The Ch'orti' Project Collaboration=== |

|||

|- |

|||

The Ch’orti’ Project is a community-based language documentation, revitalization, and reclamation project focused on the Ch’orti’ (Mayan) language of Guatemala and Honduras. It was founded in 2013 by Dr. Rebecca Forgash and Dr. Robin Quizar. The project is a collaborative effort involving MSU Denver faculty, students, Ch’orti’ community members, and others. The project is run out of and in association with MSU Anthropology's Ethnography Lab. The project is multidisciplinary and multifaceted in that it has engaged in work on producing Ch’orti’ language educational materials, preparing Ch’orti’ stories from legacy texts in the local writing system, and conducting linguistic research on various aspects of the language, among other things. |

|||

| day || kʼin || man|| winik' |

|||

|- |

|||

Current elements of the project include putting all previously written texts into the official Ch’orti’ alphabet with English and Spanish word-for-word translations, supporting individual research projects for faculty and students with on-campus and on-the-ground fieldwork, and working with archaeologists and museums to highlight the Ch’orti’ language and cultural connection with the Classic Maya civilization. A free-access internet platform of written resources available to Guatemalan scholars and Ch’orti’ speakers is also in the works, as is an initiative to help reconnect the Ch’orti’ community with the heritage held within the Classic Maya script.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://red.msudenver.edu/2019/reconnecting-with-chorti.html|title = Reconnecting with Ch'orti'|date = 11 December 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://journals.colorado.edu/index.php/cril/article/view/1347/1189|title = The Ch'orti' Project Collaboration|journal = Colorado Research in Linguistics|date = 22 August 2021|last1 = Quizar|first1 = Robin}}</ref> |

|||

| beverage || uchʼe || moon || uj |

|||

|- |

|||

===CONIMCHH=== |

|||

| earth || rum || mountain || witzir |

|||

“CONIMCHH – the Consejo Nacional Indigena Maya Ch'ortí de Honduras – is a private nonprofit organization in Honduras that facilitates the comprehensive development of its affiliated communities, including efforts promoting economic development, the recovery of ancestral lands, cultural recognition and general education.” |

|||

|} |

|||

Through strategic planning, the systematic payment of the membership dues, and the efficient use of funds and resources, they plan to achieve the technical training to introduce our goals of sustainable development to all of the necessary program areas for the communities to reach financial sustainability and the quality of the life the community members deserve, where an open community and a duty to human service prevail. |

|||

According to "A Dictionary of Chʼortiʼ Maya, Guatemala" by Kerry Hull, some words may be used as nouns (as shown above) or can double as a verb as well. For example "Witzir" can mean mountain as a noun, or 'to go uphill' as a verb. |

|||

The organization is divided into smaller groups that represent both geographical location as well as specific projects. They have a long history of fighting for social causes to try and benefit the conditions for Ch’orti’ people in Honduras.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://en.conimchh.org/index.html|title = CONIMCHH English – CONIMCHH}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="famsi.org" /> |

|||

==References== |

== References == |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

| Line 402: | Line 385: | ||

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20050308055657/http://www.utexas.edu/courses/stross/chorti/ Online version of Wisdom's Chorti Dictionary (1950)] |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20050308055657/http://www.utexas.edu/courses/stross/chorti/ Online version of Wisdom's Chorti Dictionary (1950)] |

||

*[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2I-bv4xlCao Oral Histories of the Chʼortiʼ Maya (2011)] |

*[https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2I-bv4xlCao Oral Histories of the Chʼortiʼ Maya (2011)] |

||

*[https://ailla.utexas. |

*[https://islandora-ailla.lib.utexas.edu/islandora/object/ailla%3A124489 Mayan Languages Collection of John Fought] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200926170311/https://ailla.utexas.org/islandora/object/ailla:124489 |date=2020-09-26 }} at the [[Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America]], containing several hundred recordings of Chʼortiʼ made between 1964 and 1967 in Guatemala, field notes and photographs. |

||

*[http://www.native-languages.org/chorti.htm Information about |

*[http://www.native-languages.org/chorti.htm Information about Chʼortiʼ language] |

||

{{Mayan languages}} |

{{Mayan languages}} |

||

{{Languages of Honduras}} |

{{Languages of Honduras}} |

||

{{Languages of Guatemala}} |

{{Languages of Guatemala}} |

||

* https://web.archive.org/web/20120708050908/http://www10.gencat.cat/pres_casa_llengues/AppJava/frontend/llengues_detall.jsp?id=1000&idioma=5 |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120708050908/http://www10.gencat.cat/pres_casa_llengues/AppJava/frontend/llengues_detall.jsp?id=1000&idioma=5 Linguamón Ch'orti'] |

||

{{authority control}} |

{{authority control}} |

||

| Line 421: | Line 404: | ||

[[Category:Languages of Honduras]] |

[[Category:Languages of Honduras]] |

||

[[Category:Mesoamerican languages]] |

[[Category:Mesoamerican languages]] |

||

[[Category:Chʼortiʼ]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 04:59, 15 December 2024

| Chʼortiʼ | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador |

| Region | Copán |

| Ethnicity | Chʼortiʼ |

Native speakers | (30,000 cited 2000)[1] |

Early form | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | caa |

| Glottolog | chor1273 |

| ELP | Ch'orti' |

The Chʼortiʼ language (sometimes also Chorti) is a Mayan language, spoken by the indigenous Maya people who are also known as the Chʼortiʼ or Chʼortiʼ Maya. Chʼortiʼ is a direct descendant of the Classic Maya language in which many of the pre-Columbian inscriptions using the Maya script were written.[2] Chʼortiʼ is the modern version of the ancient Mayan language Chʼolan (which was actively used and most popular between the years of A.D 250 and 850).[2]

Classification

[edit]Chʼortiʼ can be called a living "Rosetta Stone" of Mayan languages. Chʼortiʼ is an important tool for interpreting the contents of Maya glyphic writings, some of which are not yet fully understood. For several years, many linguists and anthropologists expected to grasp the Chʼortiʼ culture and language by studying its words and expressions.[3] Chʼortiʼ is spoken mainly in and around Jocotán and Camotán, Chiquimula department, Guatemala, as well as in adjacent areas of parts of western Honduras near the Copán Ruins.[4] Because the Classic Mayan language was ancestral to the modern Chʼorti, it can be used to decipher the ancient language.[2] Researchers realized that the ancient language was based more on phonetics than previously thought.[2]

The name Chʼortiʼ (with unglottalized <ch>) means 'language of the corn farmers', a reference to the traditional agricultural activity of Chʼortiʼ families. It is one of the three modern descendants of the Chʼolan language, which constitute a sub-group of Mayan languages. The other two are Chontal and Chʼol.[5] These three descendants are still spoken today. Chʼortiʼ and Chʼolti are two sub-branches belonging to Eastern Chʼolan; Chʼolti is, however, already extinct.

There are some debates among scholars about how Chʼolan should be classified. John Robertson considered the direct ancestor of colonial Chʼoltiʼ to be the language of the Mayan script (also known as Mayan Glyphs). The language of the Mayan Glyphs is described as 'Classic Chʼoltiʼan' by John Robertson, David Stuart, and Stephen Houston. The language of the Mayan script is thus the ancestor of Chʼortiʼ. The relationship is shown in the chart below.[4]

Endangerment

[edit]The Chʼortiʼ people are descendants of the people who lived in and around Copán, one of the cultural capitals of the ancient Maya area. This covers parts of modern-day Honduras and Guatemala. Chʼorti is considered an endangered language as well as an endangered culture.

Geographic location

[edit]

This region is the only region in the world that Chʼorti speakers can be found. Although the area is completely shaded in, the majority of speakers reside in Guatemala, while the rest are sparsely distributed throughout the rest of the area.[6]

Honduras

[edit]The government of Honduras has been trying to promote a uniform national language of Spanish, and therefore discourages the use and teaching of native languages such as Chʼorti. The Chʼortiʼ people in Honduras face homogenization and have to assimilate to their surroundings. The government has been clashing with the Chʼorti people over land disputes from the 1800s, which puts the people (and thus the language) at risk. In 1997, 2 prominent Chʼorti leaders were assassinated. This assassination is just one example of many cases where Chʼorti advocates have been harmed or killed. Every one of these killings reduces the number of Chʼorti speakers. As of right now, there are only 10 remaining native speakers in Honduras.[7]

Guatemala

[edit]The government of Guatemala has been more supportive of Chʼorti speakers and has promoted programs that encourage the learning and teaching of Chʼorti. The Chʼorti's in Guatemala wear traditional clothing, unlike their counterparts in Honduras, who wear modern-day clothing.[7] Currently there are about 55,250 Chʼorti speakers in Guatemala. Even though Guatemala has established Spanish as its official language, it supports the teaching of these native languages.

Ethnonyms: Cholotí, Chorté, Chortí

[edit]The majority of Chʼortiʼ live in the Chiquimula Department of Guatemala, approximately 52,000. The remaining 4,000 live in Copán, Honduras. The Kʼicheʼ Maya however, dominated the Chʼortiʼ dating back to the early fifteenth century. Warfare as well as disease devastated much of the Chʼortiʼ during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Much of their land was lost to the Guatemalan government in the nineteenth century as well. More recently, 25 percent of the Guatemalan Chʼortiʼ went to the United States during the 1980s to escape political persecution.[8]

Phonology and orthography

[edit]The Chʼortiʼ have their own standard way of writing their language. However, inaccurate ways to represent phonemes led to some variation among recent publications.[9][10]

Consonants

[edit]| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p ⟨p⟩ | t ⟨t⟩ | k ⟨k⟩ | ʔ ⟨ʼ⟩ | |

| glottalic | ɓ ⟨bʼ⟩ | tʼ ⟨tʼ⟩ | kʼ ⟨kʼ⟩ | |||

| voiced[a] | (b ⟨b⟩) | (d ⟨d⟩) | (ɡ ⟨g⟩) | |||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts ⟨tz⟩ | tʃ ⟨ch⟩ | |||

| glottalic | tsʼ ⟨tzʼ⟩ | tʃʼ ⟨chʼ⟩ | ||||

| Fricative | s ⟨s⟩ | ʃ ⟨x⟩ | x ⟨j⟩[b] | h ⟨j⟩[b] | ||

| Trill | r ⟨r⟩ | |||||

| Approximant | l ⟨l⟩ | j ⟨y⟩ | w ⟨w⟩ | |||

- ^ /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/ usually only appear in Spanish loan words.

- ^ a b ⟨j⟩ has two pronunciations, as either a voiceless velar fricative [x] or a voiceless glottal fricative [h]. Classic Mayan differentiated between the two. This differentiation can be seen in some Chʼortiʼ literature, such as with the texts by Wisdom.

The consonants of Chʼortiʼ include glottal stop [ʼ], b, bʼ, ch, chʼ, d, g, j, k, kʼ, l, m, n, p, r, s, t, tʼ, tz, tzʼ, w, x, y.

The ⟨w⟩ and ⟨y⟩ are semivowels.

Vowels

[edit]| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

The vowels consist of a, e, i, o, and u.[10]

Vowel clusters

[edit]| Characters we[who?] use | Sometimes also used | IPA symbol | Chʼortiʼ pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| aa | ā, aꞏ, a꞉ | a | Like regular a but held longer |

| ee | ē, eꞏ, e꞉ | e | Like e only held longer |

| ii | ī, iꞏ, i꞉ | i | Like i only held longer |

| oo | ō, oꞏ, o꞉ | o | Like o only held longer |

| uu | ū, uꞏ, u꞉ | u | Like u only held longer |

When two vowels are put together in Chʼortiʼ the second vowel always takes precedence and then is always followed by a glottal stop. Chʼortiʼ doesn't have any long vowels. According to historians, long vowels occur in Classical Mayan, but have been lost in modern Chʼortiʼ.

In Chʼortiʼ language, aa or a꞉ is used as aʼ or Aʼ, we can see this pattern with all vowel clusters including eʼ, Iʼ, oʼ and uʼ.

Some examples of words with vowel clusters are꞉

- Jaʼx [xaʔʃ] = Her, ella

- Weʼr [weʔr] = meat, carne

- Bʼiʼx [pʼiʔʃ] = seed, semilla

- Tunoʼron [tunoʔɾon] = everyone, todos

- Kuʼm [kuʔm] = egg, huevo [11]

Syntax

[edit]The aspectual system of Chʼortiʼ language changed to a tripartite pronominal system which comes with different morphemes used for the subject of transitive verbs, the object of transitive verbs and the subject of intransitive completive verbs, and a third set of pronouns only used for the subject of incompletive intransitive verbs.[12]

Chʼortiʼ tripartite pronominal system (data from Hull 2005)

e

def

sitzʼ

boy

u-buyi-Ø

A-3-chop-B-3

e

def

siʼ

wood

'The boy chops the wood (into tiny pieces)'

intzaj

sweet

lokʼoy-Ø

go.out-B-3

e

def

peʼych

tomato

'The tomato turned out delicious'

e

def

kʼin

sun

a-lokʼoy

C-1-go.out

ta

prep

ixner

going

kʼin

sun

'The sun sets in the west'

Basic word order

[edit]In the Chʼortiʼ language and other Mayan sentences it always starts with verbs but also there are agents or patients added and in which they are commonly represented by the acronym VOS, meaning verb-object-subject. The following rules apply VSO, SVO, SOV, OVS, OSV.[13]

In most of the Chʼortiʼ language there are phrases surrounding transitive verbs and they are order subject first (first-most) and it's followed by the verb then the object (SVO).[14]

Adjectives with attributive function

[edit]The adjective works together with the nouns as a modifier formed with a noun phrase that plays some syntactic role, object etc.[13]

Predicative adjective indicate the size, color or state

E bʼikʼit

adjective

The little

yurwobʼ

noun

chicks

chamobʼ

verb

died

inchoni

verb

I am selling

e yaxax

adjective

green

pe'ych

noun

tomato

Chʼortiʼ has many other different forms, in the following sentence the words that appear to be bold is a preposition and underline one is a relational noun.[13]

E

The

chij

horse

numuy

passed

tu't

in.front.of

e

the

max-tak

child-PL

"The horse passed in front of the children"

Morphology

[edit]Verb inflection

[edit]| Ergative (Set A) |

Absolutive (Set B) |

Subjective (Set C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person |

singular | in-/ni- | -en | in- |

| plural | ka- | -on | ka- | |

| 2nd person |

singular | a- | -et | i- |

| plural | i- | -ox | ix- | |

| 3rd person |

singular | u- | -Ø | a- |

| plural | u-...-obʼ | -obʼ | aʼ...-obʼ | |

Examples of inflected verbs from Isidro González's stories (John Fought, 1972):

| Uninflected Verb | Inflected Verb |

|---|---|

ixin "to go" |

ixinobʼ go-A3-PL "they went" Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

ira “to see” |

uwira E3-see-A3 “he sees it” Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

kojko “to guard” |

ukojkobʼ E3-guard-A3-PL “they guard over it” Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

ixin “to go” |

aʼxin S3-go “he goes” Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help); |

Possessions

[edit]Tak is plural for women and childrenʼ

- ijchʼok-tak "little girls"

- max-tak "children, young ones, family" (max does not occur without -tak)

- ixik-tak "women"

These are the only instances encountered. It is worthy of notice that ixkaʼr "wife", chʼurkabʼ "baby" and ar "offspring" take -ob'.

obʼ is a general plural. The suffix can be found in nouns, verbs, adjectives, and participials.

Examples on possessives:

e

DEF.ART

mut-obʼ

bird-3.PL

war

PROG

u-bʼax-i-obʼ

3A-pull up-THEM-3.PL

ni-jinaj

1A.SG-maize plant

The birds are pulling my maize plant. Unknown glossing abbreviation(s) (help);

Yar-obʼ

small-3.PL

bʼikʼit

small variety of

ruch

gourd container

And then come two little gourds,... (f330040)

Vocabulary

[edit]The following list contains examples of common words in the Chʼortiʼ language:

| English | Chʼortiʼ | English | Chʼortiʼ |

|---|---|---|---|

| big | nixiʼ | fire | kʼajkʼ |

| bird | mut | here | tara |

| cold | insis | what | tukʼa |

| dog | txʼiʼ | husband | noxibʼ |

| day | kʼin | man | winik' |

| beverage | uchʼe | moon | uj |

| earth | rum | mountain | witzir |

According to "A Dictionary of Chʼortiʼ Maya, Guatemala" by Kerry Hull, some words may be used as nouns (as shown above) or can double as a verb as well. For example "Witzir" can mean mountain as a noun, or 'to go uphill' as a verb. [9]

References

[edit]- ^ Chʼortiʼ at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d Houston, S, J Robertson, and D Stuart. "The language of Classic Maya inscriptions." Current Anthropology 41.3 (2000): 321–356. Print.

- ^ Keys, David (2003-12-07). "'Lost' Sacred Language of the Maya Is Rediscovered". mayanmajix.com. Archived from the original on 2003-12-19.

- ^ a b Hull, Kerry M. (2003). "Verbal art and performance in Chʼortiʼ and Maya hieroglyphic writing". The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ Mathews, Peter; Bíró, Péter. "Maya Hieroglyphs and Mayan Languages". research.famsi.org.

- ^ • McAnany, Patricia, and Shoshaunna Parks. "Casualties of Heritage Distancing Children, Chʼortiʼ Indigeneity, and the Copan Archaeoscape." Current Anthropology 53.1 (2012): 80–107. Print.

- ^ a b "Minority Rights Group International : Honduras : Lenca, Miskitu, Tawahka, Pech, Maya, Chortis and Xicaque". World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ^ Chenier, Jacqueline; Sherwood, Steve (2013-10-27). "Copan: Collaboration for Identity, Equity and Sustainability (Honduras)". srdis.ciesin.columbia.edu. Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM). Archived from the original on 2007-06-14.

- ^ a b c Hull, Kerry (2005). "A Dictionary of Chʼortiʼ Maya, Guatemala" (PDF). FAMSI.org.

- ^ a b Pérez Martínez, Vitalino(1994) Gramática del idioma chʼortíʼ. Antigua, Guatemala: Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín.

- ^ "Chorti Maya Pronunciation Guide, Alphabet and Phonology". www.native-languages.org. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ Law, Danny; Robertson, John; Houston, Stephen (2006). "Split Ergativity In The History Of The Chʼolan Branch Of The Mayan Language Family". International Journal of American Linguistics. 72 (4). University of Texas at Austin: 415–450. doi:10.1086/513056.

- ^ a b c d Pérez, Lauro (2004–2008). "GRAMÁTICA PEDAGÓGICA Chʼortiʼ" (PDF). Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ Dugan, James (May 20, 2013). "The grammar of Chʼortiʼ Maya Folktales".

- ^ Quizar, Robin. 1994. "Motion Verbs in Chʼortiʼ." Función 15–16. 211–229.

- ^ Wichmann, Søren (1999). A CHʼORTIʼ MORPHOLOGICAL SKETCH. p. 153.

External links

[edit]- Online version of Wisdom's Chorti Dictionary (1950)

- Oral Histories of the Chʼortiʼ Maya (2011)

- Mayan Languages Collection of John Fought Archived 2020-09-26 at the Wayback Machine at the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America, containing several hundred recordings of Chʼortiʼ made between 1964 and 1967 in Guatemala, field notes and photographs.

- Information about Chʼortiʼ language