Nixtamalization: Difference between revisions

m proper grammar |

the link between tryptophan and niacin isn't made explicit until much later in the page, so an explanation in the Hed is helpful |

||

| (403 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{More footnotes|date=August 2010}} |

|||

'''Nixtamalization''' is the process whereby ripe [[maize]] grains are soaked and cooked in an [[alkaline]] solution, usually [[Lime (mineral)|lime]] based, to cause the transparent outer hull, the [[pericarp]], to separate from the grain. This process has multiple benefits including enabling the grain to be more effectively ground; increasing protein and vitamin content availability; improving flavor and aroma and reduction of [[mycotoxin]]s. The recorded [[Aztec]] word for the product of this process is '''nixtamal'''. The term can also be used to describe the removal of the pericarp from any grain such as [[sorghum]] by an alkali process. |

|||

{{Use American English|date = April 2019}} |

|||

{{Short description|Procedure for preparing corn to eat}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date = April 2019}} |

|||

[[File:Tortilleras Nebel.jpg|right|thumb|250px|An 1836 [[lithograph]] of [[tortilla]] production in rural Mexico]] |

|||

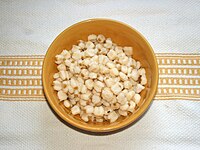

[[File:Hominy (maize).JPG#file|thumb|right|200px|Bowl of hominy (nixtamalized corn kernels)]] |

|||

'''Nixtamalization''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|n|ɪ|ʃ|t|ə|m|ə|l|ɪ|ˈ|z|eɪ|ʃ|ən}} {{respell|nish|tə|mə|lih|ZAY|shən}}) is a process for the preparation of [[maize]], or other [[cereal grain|grain]], in which the grain is soaked and [[cooking|cooked]] in an [[alkaline]] solution, usually [[limewater]] (but sometimes aqueous [[alkali metal]] [[carbonate]]s),<ref name=ml>{{cite web |last=Thigpen |first=Susan |title=Hominy – Mountain Recipe |url=http://www.mtnlaurel.com/recipes/160-hominy-mountain-recipe.html |work=The Mountain Laurel |access-date=17 November 2013 |date=October 1983}}</ref> washed, and then [[hulling|hulled]]. The term can also refer to the removal via an alkali process of the [[pericarp]] from other grains such as [[sorghum]]. |

|||

Nixtamalized corn has several benefits over unprocessed grain: It is more easily ground, its [[nutrition]]al value is increased, [[Flavor (taste)|flavor]] and [[aroma]] are improved, and [[mycotoxin]]s are reduced by up to 97–100% (for [[aflatoxin|aflatoxins]]).<ref>{{cite book |title=Mycotoxins in Food, Feed and Bioweapons |pages=39–49 |editor1=M. Rai |editor2=A. Varma |publisher=Springer-Verlag |location=Berlin Heidelberg |year=2010 |chapter-url=http://libcatalog.cimmyt.org/download/reprints/98545.pdf |chapter=The Destruction of Aflatoxins in Corn by "Nixtamalización" |author=Doralinda Guzmán-de-Peña |access-date=2019-04-12 |doi=10.1007/978-3-642-00725-5_3|isbn=978-3-642-00724-8 }}</ref> |

|||

Lime and ash are highly alkaline: the alkalinity helps the dissolution of [[hemicellulose]], the major glue-like component of the maize cell walls, and loosens the hulls from the kernels and softens the maize.<ref name="researchgate" /> The [[tryptophan]] in corn proteins is made more available for human absorption, thus helping to prevent niacin deficiency [[pellagra]].<ref name=fao92/>{{rp|at=§5.2}} Tryptophan is the metabolic precursor of endogenous niacin (Vitamin B<sub>3</sub>). |

|||

Some of the corn oil is broken down into emulsifying agents (monoglycerides and diglycerides), while bonding of the maize proteins to each other is also facilitated. The divalent calcium in lime acts as a cross-linking agent for protein and polysaccharide acidic side chains.<ref>{{cite book |title= On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen |author= Harold McGee |publisher= [[Charles Scribner's Sons|Scribner]] |location= New York, New York (USA) |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=bKVCtH4AjwgC&q=nixtamalization |date= 2004 |page= 478 |isbn= 978-0-684-80001-1 |access-date= 23 January 2013}}</ref> |

|||

While [[cornmeal]] made from untreated ground maize is unable by itself to form a dough on addition of water, nixtamalized cornmeal will form a dough, called [[masa]]. These benefits make nixtamalization a crucial preliminary step for further processing of maize into food products, and the process is employed using both traditional and industrial methods in the production of [[tortilla]]s and [[tortilla chip]]s (but not [[corn chip]]s), [[tamale]]s, [[hominy]], and many other items. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

In the [[Aztec]] language [[Nahuatl]], the word for the product of this procedure is {{lang|nah|nixtamalli}} or {{lang|nah|nextamalli}} ({{IPA-nah|niʃtaˈmalːi|pron}} or {{IPA-nah|neʃtaˈmalːi|}}), which in turn has yielded [[Mexican Spanish]] {{lang|es-MX|nixtamal}} ({{IPA|es|nistaˈmal|}}). The Nahuatl word is a compound of {{lang|nah|nextli}} "[[calcium hydroxide|lime]] ashes" and {{lang|nah|tamalli}} "unformed/cooked corn dough, [[tamale|tamal]]".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Días Roig|first1=Mercedes|last2=Miaja|first2=María Teresa|publisher=El Colegio de México|title=Naranja dulce, limón partido|edition=1st|language=es|year=1979|location=México City|isbn=968-12-0049-7|page=137}}</ref> The term ''nixtamalization'' can also be used to describe the removal of the pericarp from any grain by an alkali process, including maize, [[sorghum]], and others. When the unaltered Spanish spelling {{lang|es-MX|nixtamalización}} is used in written English, however, it almost exclusively refers to maize. |

|||

The labels on packages of commercially sold tortillas prepared with nixtamalized maize usually list ''corn treated with lime'' as an ingredient in English, while the Spanish versions list {{lang|es-MX|maíz nixtamalizado}}. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

This ancient process was first developed in [[Mesoamerica]] where maize was developed. There is no precise date when the technology was developed though the earliest physical evidence points to Guatemala 1200-1500 [[Common Era|BCE]]. The ancient [[Aztec]]s and [[Mayans]] developed nixtamalization but the ancient [[Inca]] did not. |

|||

[[File:Dried Maize Mote from Oaxaca.png|thumb|right|Dried, treated maize sold in [[Oaxaca]], Mexico ([[quarter (United States coin)|US quarter]] and [[Mexican peso]] shown for scale)]] |

|||

The process of nixtamalization was first developed in [[Mesoamerica]], where [[maize]] was originally cultivated. There is no precise date when the technology was developed, but the earliest evidence of nixtamalization is found in Guatemala's southern coast, with equipment dating from 1200 to 1500 BC.<ref name="staller">{{cite book|last1=Staller|first1=John E.|last2=Carrasco|first2=Michael|title=Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica|year=2009|publisher=Springer-Verlag|location=Berlin|page=317|isbn=978-1-4419-0471-3}}</ref> |

|||

How nixtamalization was discovered is not known, but one possibility may have been through the use of hot stones (see [[pot boiler]]) to boil corn in early cultures which did not have cooking vessels robust enough to put directly on fire or coals. In limestone regions like those in Guatemala and southern Mexico, heated chunks of limestone would naturally be used, and experiments show that hot limestone makes the cooking water sufficiently alkaline to cause nixtamalization. Archaeological evidence supporting this possibility has been found in southern Utah, United States.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups |journal=Journal of Archaeological Science |volume=40 |pages=35–44 |doi=10.1016/j.jas.2012.05.044 |year=2013 |last1=Ellwood |first1=Emily C. |last2=Scott |first2=M. Paul |last3=Lipe |first3=William D. |last4=Matson |first4=R.G. |last5=Jones |first5=John G. |issue=1 |bibcode=2013JArSc..40...35E |url=https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1172&context=agron_pubs }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Earliest evidence of nixtamalization is found in Guatemala's southern coast with equipment dating from 1200–1500 [[Common Era|BCE]]. The ancient [[Maya civilization|Maya]] and the [[Aztecs]] used lime ([[calcium oxide]]) and ashes in creating alkaline solutions, while the tribes of North America used [[sodium carbonate]](??), which occurred naturally, or ashes. It is noted that contemporary Maya use the ashes of burnt mussels. The process has not really declined in usage in the Mesoamerican region though there has been a decline in North America. Many North American Native American tribes, such as the [[Huron]] no longer use the process; however residents of the Southeastern United States still produce and eat [[hominy]]. The U.S. version of hominy is produced by whole maize grains, preferably white when eaten in the form of grits, mixed with scalding water mixed with a chemical solution, such as a mild [[lye]] or slaked lime ([[sodium hydroxide]] or [[potassium hydroxide]] solution), traditionally derived from wood ash, until the soaking forces the kernel to expand so the hull and germ split. The kernel is removed and dried. After drying, the whole kernels are soaked in water and a solution mixed with limestone or wood ash is used to expand the kernels, which are then boiled. It is also prepared into [[grits]] which are dried ground hominy. |

|||

The [[Aztec]] and [[Maya civilization|Mayan]] civilizations developed nixtamalization using slaked lime ([[calcium hydroxide]]) and lye ([[potassium hydroxide]]) to create alkaline solutions. The [[Chibcha]] people to the north of the ancient [[Inca]] also used calcium hydroxide (also known as "cal"), while the tribes of North America used [[soda ash]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The nixtamalization process was very important in the early Mesoamerican diet, as there is very little [[niacin]] in corn and the tryptophan within is unavailable without processing.<ref name=fao92/>{{rp|at=§5.2}} A population that depends on untreated maize as a [[staple food]] risks malnourishment and is more likely to develop [[deficiency disease]]s such as [[pellagra]], niacin deficiency, or [[kwashiorkor]], the absence of certain amino acids that maize is deficient in. Maize cooked with lime or other alkali provided bioavailable niacin to Mesoamericans. Beans provided the otherwise missing amino acids required to balance maize for [[complete protein]].<ref name=fao92/>{{rp|at=§8}} |

|||

{{not verified}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Maize was introduced by [[Christopher Columbus]] in the 15th century, with it being grown in [[Spain]] as early as [[1498]]. Europeans accepted maize within a generation, but they did not adopt the nixtamalization process, perhaps because the Europeans had more efficient milling processes and so did not need to remove the [[pericarp]]. However, without the process [[maize]] is a much less beneficial foodstuff, leading to outbreaks of [[pellagra]] and [[kwashiorkor]] in areas where it became a staple grain, such as certain regions of [[Italy]] and [[Africa]]. Because of this lack of understanding of the importance of the processing, maize suffered the stigma of being an unhealthy grain that could stave off starvation but lead to malnourishment. For example, this is why [[polenta]] was considered the poor person’s food in Italy until its more recent increase in status as gourmet food. |

|||

The spread of maize cultivation in the Americas was accompanied by the adoption of the nixtamalization process. Traditional and contemporary regional cuisines (including [[Maya cuisine]], [[Aztec cuisine]], and [[Mexican cuisine]]) included, and still include, foods based on nixtamalized maize. |

|||

The process has not substantially declined in usage in the [[Mesoamerican region]], though there has been a decline in North America. Many Native North American tribes, such as the [[Wyandot people|Huron]], no longer use the process.{{Citation needed|date=February 2008}} In some Mesoamerican and North American regions, dishes are still made from nixtamalized maize prepared by traditional techniques. The [[Hopi]] produce sodium carbonate from ashes of various native plants and trees.<ref>{{cite book|access-date=2007-10-15|title=Diabetes As a Disease of Civilization: The Impact of Culture Change on Indigenous People |author1=Jennie Rose Joe |author2=Robert S. Young |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Io0sdbsTK08C |year=1993 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-013474-2}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B_y0ekzJvwQC|title=American Indian Food|author=Linda Murray Berzok|year=2005|publisher=Greenwood Press|access-date=2007-10-15 |isbn=978-0-313-32989-0}}</ref> Some contemporary Maya use calcium salts in the form of ashes of burnt mussel shells or heated limestone.<ref>{{cite web |title=Guatemalan Tortillas: How To Make Them And Why To Eat Them |url=https://www.healthacrosscultures.com/guatemalan-tortillas/ |access-date=2018-08-03 }}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Early evidence of maize occurs with the Portuguese who grew the plant in the [[Congo]] as early as [[1560]]. Maize has been adapted as a major grain in parts of Africa. However, the nixtamalization process has not been widely adapted. |

|||

In the United States, European settlers did not always adopt the nixtamalization process, except in the case of hominy grits, though maize became a staple among the poor of the southern states. This led to endemic [[pellagra]] in poor populations throughout the southern US in the early 20th century.<ref>{{cite book |last=Latham |first=Michael C. |title=Human Nutrition in the Developing World |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_diGLEXZEGh8C |year=1997 |publisher=Food & Agriculture Org. |isbn=9789251038185 |page=[https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_diGLEXZEGh8C/page/n189 183]}}</ref> A more varied diet and fortification of wheat flour, the other staple food, have essentially eliminated this deficiency.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Rucker |first1=Robert B. |last2=Zempleni |first2=Janos |last3=Suttie |first3=John W. |author4=Donald B. McCormick |author4-link=Donald B. McCormick |title=Handbook of Vitamins, Fourth Edition |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6fYso23Mi5IC&pg=PA192 |year=2010 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-4200-0580-6 |page=192}}</ref> |

|||

== Production == |

|||

[[Image:Nixtamal.jpg|right|400px]] |

|||

[[Hemicellulose]] is one of the major components of plant cell walls and can be dissolved in alkaline solutions. This dissolving of the hemicellulose loosens the pericarp so it can be removed. The germ of the grain remains after the pericarp is removed by washing. The cooking in alkaline solution removes certain starch granules and changes to the protein matrix which allows the easier access to proteins and nutrients from the [[endosperm]] of the kernel. |

|||

==Process== |

|||

Because of the soaking and cooking, the grains take in moisture and [[calcium]] from the solution and certain chemicals from the germ are released that allow the nixtamal to be ground more effectively and the final masa dough to be less likely to tear and break down. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Nixtamalized Corn maize El Salvador recipe.jpg|thumb|right|Dry maize, boiled in lime (right) and untreated (left). In this case, typical of El Salvador, a pound of maize (454 g) is boiled with a tablespoon of lime (15 mL) for 15 minutes, left to stand for a few hours, and washed with fresh water. The hulls are removed, and the kernels ground into ''masa''. Exact methods vary by use and region.]] |

|||

In the first step of nixtamalization, kernels of dried maize are [[Alkaline hydrolysis|cooked in an alkaline solution]] at or near the mixture's boiling point. After cooking, the maize is steeped in the cooking liquid for a period. The length of time for which the maize is boiled and soaked varies according to local traditions and the type of food being prepared, with cooking times ranging from a few minutes to an hour, and soaking times from a few minutes to about a day. |

|||

Production in [[Mexico]] uses lime water ([[CaO]] 1% based on corn weight), boiled for a wide variety of time (a few minutes to an hour), soaked overnight, and then washed to remove solution and pericarp. The nixtamal is then ground. |

|||

During cooking and soaking, a number of chemical changes take place in the grains of maize. Because plant cell wall components, including [[hemicellulose]] and [[pectin]], are highly soluble in alkaline solutions, the kernels soften and their pericarps (hulls) loosen. The grain hydrates and absorbs calcium or [[potassium]] (depending on the alkali used) from the cooking solution. Starches swell and [[starch gelatinization|gelatinize]], and some starches disperse into the liquid. Certain chemicals{{which|date=August 2019}} from the germ are released that allow the cooked grains to be ground more easily, yet make dough made from the grains less likely to tear and break down. Cooking changes the grain's protein matrix, which makes proteins and nutrients from the [[endosperm]] of the kernel more available to the human body. |

|||

Industrial production in Mexico falls into two categories: the family owned [[tortilla]] factory and large-scale flour production which can produce 30-80 tonnes per day. The family owned tortilla factory uses the traditional nixtamal method except with the addition of mechanical equipment such as rotary mills and tortilla makers, while large-scale production does extensive sorting, storing, conversion of maize to nixtamal, sprays or pressure washes, grinds, dries, sifts and regrinds before packing into bags. |

|||

=== Extraction === |

|||

In contrast in [[Guatemala]] the lime concentration varies from 0.17-.058 by weight and cooked from 46-67 minutes at 94C. |

|||

After cooking, the alkaline liquid (known as '''nejayote'''), containing dissolved hull, starch, and other corn matter, is decanted and discarded (or sometimes used for making [[amate]] bark paper).<ref>{{cite book |last= von Hagen |first= Victor Wolfgang |author-link= Victor Wolfgang von Hagen |title= The Aztec and Maya Papermakers |publisher= J. J. Augustin Publisher |year= 1944 |page= 57 |isbn= 978-0-87817-206-1}}</ref> The kernels are washed thoroughly of remaining nejayote, which has an unpleasant flavor. The [[pericarp]] is then removed, leaving the [[endosperm]] of the [[whole grain|grain]] with or without the [[cereal germ|germ]], depending on the process.<ref>{{cite web |title=What is Hominy? |url=http://www.buzzle.com/articles/what-is-hominy.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110202071113/http://www.buzzle.com/articles/what-is-hominy.html |url-status=usurped |archive-date=February 2, 2011 |access-date=2011-01-31}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology |url=http://74.6.238.252/search/srpcache?ei=UTF-8&p=nixtamalization+germ&fr=altavista&u=http://cc.bingj.com/cache.aspx?q=nixtamalization+germ&d=4892844087183950&mkt=en-US&setlang=en-US&w=f7949c99,15694ecd&icp=1&.intl=us&sig=Rl3KbkpqQ_QD4uM69aUYCg-- |access-date=2011-01-31 }}{{dead link|date=April 2018 |bot=SheriffIsInTown |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Technological Limitations of the Nixtamalization Process |url=http://www.maiztortilla.com/en/introduction/limitations.htm |access-date=2011-01-31 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110714022421/http://www.maiztortilla.com/en/introduction/limitations.htm |archive-date=2011-07-14 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Selective Nixtamalization of Fractions of Maize Grain |url=http://academic.research.microsoft.com/Paper/12460489.aspx |access-date=2011-01-31 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728100059/http://academic.research.microsoft.com/Paper/12460489.aspx |archive-date=2011-07-28 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=What's the difference between corn meal and corn masa? |date=November 4, 2010 |url=http://www.joepastry.com/2010/11/04/ |access-date=2011-01-31 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110713112935/http://www.joepastry.com/2010/11/04/ |archive-date=2011-07-13 }}</ref> This hulling is performed by hand, in traditional or very small-scale preparation, or mechanically, in larger scale or industrial production. |

|||

The prepared grain is called hominy or nixtamal. Nixtamal has many uses, contemporary and historic. Whole nixtamal may be used fresh or dried for later use. Whole nixtamal is used in the preparation of [[pozole]], [[menudo (soup)|menudo]], and other foods. Ground fresh nixtamal is made into ''masa'' (nixtamal [[dough]]) and used to make [[tortilla]]s, [[tamale]]s, and [[pupusa]]s. Dried and ground, it is called ''masa harina'' or instant ''masa'' flour, and is reconstituted and used like ''masa''. |

|||

==Nutritional and Health Benefits== |

|||

The nutritional benefits are many with nixtamalization. [[Calcium]] is increased by 750% with 85% available for digestion. Other vital minerals increase as well including [[iron]], [[copper]] and [[zinc]] which maybe due to the lime being used or the vessels being used to make nixtamal. [[Niacin]] is made available for digestion which would otherwise be inaccessible with non-processed maize. Another important aspect of this process’ benefit is the significant reduction (90-94%) of the [[mycotoxin]]s ''[[Fusarium vierticilloides]]'' and ''[[Fusarium proliferatum]]'' which produce [[fumosin]]s which cause disease in animals and possible [[carcinoma]] in humans. |

|||

The term hominy may refer to whole, coarsely ground, or finely ground nixtamal, or to a cooked porridge (also called [[samp]]) prepared from any of these. |

|||

If nixtamal is allowed to ferment, [[riboflavin]], protein, and niacin increase further in addition to amino acids, such as [[tryptophan]] and [[lysine]]. It has been calculated that residents of rural [[Mexico]] acquire 50% of their daily protein and 70% of calories from nixtamal tortillas. Because of the importance of nixtamal to the diet, the Mexican government has mandated that nixtamal flour have further vitamin fortification with vitamins [[Vitamin A|A]] and [[Vitamin C|C]], [[niacin]], [[riboflavin]], [[folic acid]], [[iron]] and [[zinc]]. |

|||

===Enzymatic nixtamalization=== |

|||

An alternative process for use in industrial settings has been developed known as '''enzymatic nixtamalization''', which uses [[protease]] enzymes to accelerate the changes that occur in traditional nixtamalization, a technique borrowed from modern [[corn wet-milling]]. In this process, corn or corn meal is first partially hydrated in hot water, so that enzymes can penetrate the grain, then soaked briefly (for approximately 30 minutes) at {{convert|50|–|60|C}} in an alkaline solution containing protease enzymes. A secondary enzymatic digestion may follow to further dissolve the pericarp. The resulting nixtamal is ground with little or no washing or hulling. |

|||

By pre-soaking the maize, minimizing the alkali used to adjust the pH of the alkaline solution, reducing the cooking temperature, accelerating processing, and reusing excess processing liquids, enzymatic nixtamalization can reduce the use of energy and water, lower nejayote (alkaline wastewater) production, decrease maize lost in processing, and shorten the production time (to approximately four hours) compared to traditional nixtamalization.<ref>{{cite patent |country=US |number=6428828 |status=patent |title= Enzymatic process for nixtamalization of cereal grains |gdate=2002-08-06 |fdate=2000-08-22 |inventor1-first=David S. |inventor1-last=Jackson |inventor2-first=Deepak |inventor2-last=Sahai |assign1=NuTech Ventures Inc |url=https://patents.google.com/patent/US6428828B1/en}}</ref> |

|||

==Impact on health== |

|||

The primary nutritional benefits of nixtamalization arise from the alkaline processing involved. The processing renders the protein more digestible, allowing tryptophan to be absorbed by humans. Humans can convert [[tryptophan]] into niacin, thus helping to prevent [[pellagra]]. Other measures of [[protein quality]] are also improved.<ref name=fao92>{{cite book |title=Maize in human nutrition |date=1992 |publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |location=Rome |isbn=9789251030134|url=https://www.fao.org/3/T0395E/T0395E00.htm}} – Section 5.2 "Lime-treated maize (part II)", Section 8 "Improvement of maize diets"</ref>{{rp|at=§5.2}} It was originally thought that the anti-pellagra action stems from increased availability of niacin (compared to a hemicellulose-bound form called "niacytin"),<ref name="researchgate">{{Cite journal |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228453826 |title=Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology to process maize at small-scale with great potential for improving the nutritional quality of maize based foods |last=Wacher |first=Carmen |date=2003-01-01 |journal=Food Based Approaches for a Healthy Nutrition in Africa |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180305202539/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228453826_Nixtamalization_a_Mesoamerican_technology_to_process_maize_at_small-scale_with_great_potential_for_improving_the_nutritional_quality_of_maize_based_foods |archive-date=2018-03-05}}</ref> but multiple experiments have disproven this theory.<ref name=fao92/>{{rp|at=§5.2}} |

|||

Secondary benefits can arise from the grain's absorption of minerals from the alkali used or from the vessels used in preparation. These effects can increase [[calcium]] (by 750%, with 85% available for absorption), [[iron]], [[copper]], and [[zinc]].<ref name="researchgate"/> |

|||

Nixtamalization significantly deactivates (by 90–94%) [[mycotoxin]]s produced by ''[[Fusarium verticillioides]]'' and ''[[Fusarium proliferatum]]'', molds that commonly infect maize, the toxins of which are putative [[carcinogens]].<ref name="researchgate"/> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*[http://www.univouaga.bf/fn2ouaga2003/abstracts/0715_FP_O4_Mexico_Wacher.pdf Wacher Carmen “Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology to process maize at small-scale with great potential for improvingthe nutritional quality of maize based foods” (2003)] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[http://www.fao.org/documents/show_cdr.asp?url_file=/docrep/T0395E/T0395E07.htm Food and Agricultural Organization, United Nations. Maize in Human Nutrition] |

|||

*Smith, C. Wayne, Javier Betrán and E. C. A. Runge (editors). Corn: Origins, History and Technology (2004) p. |

*Smith, C. Wayne, Javier Betrán and E. C. A. Runge (editors). Corn: Origins, History and Technology (2004) p. 275 {{ISBN|0-471-41184-1}} |

||

{{Refend}} |

|||

{{Corn}} |

|||

{{Cooking techniques}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Cooking techniques]] |

[[Category:Cooking techniques]] |

||

[[Category:Mexican cuisine]] |

[[Category:Mexican cuisine]] |

||

[[Category:Mesoamerican cuisine]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Food processing]] |

|||

[[ |

[[de:Mais#Nixtamalisation]] |

||

Latest revision as of 17:15, 19 December 2024

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2010) |

Nixtamalization (/ˌnɪʃtəməlɪˈzeɪʃən/ nish-tə-mə-lih-ZAY-shən) is a process for the preparation of maize, or other grain, in which the grain is soaked and cooked in an alkaline solution, usually limewater (but sometimes aqueous alkali metal carbonates),[1] washed, and then hulled. The term can also refer to the removal via an alkali process of the pericarp from other grains such as sorghum.

Nixtamalized corn has several benefits over unprocessed grain: It is more easily ground, its nutritional value is increased, flavor and aroma are improved, and mycotoxins are reduced by up to 97–100% (for aflatoxins).[2]

Lime and ash are highly alkaline: the alkalinity helps the dissolution of hemicellulose, the major glue-like component of the maize cell walls, and loosens the hulls from the kernels and softens the maize.[3] The tryptophan in corn proteins is made more available for human absorption, thus helping to prevent niacin deficiency pellagra.[4]: §5.2 Tryptophan is the metabolic precursor of endogenous niacin (Vitamin B3).

Some of the corn oil is broken down into emulsifying agents (monoglycerides and diglycerides), while bonding of the maize proteins to each other is also facilitated. The divalent calcium in lime acts as a cross-linking agent for protein and polysaccharide acidic side chains.[5]

While cornmeal made from untreated ground maize is unable by itself to form a dough on addition of water, nixtamalized cornmeal will form a dough, called masa. These benefits make nixtamalization a crucial preliminary step for further processing of maize into food products, and the process is employed using both traditional and industrial methods in the production of tortillas and tortilla chips (but not corn chips), tamales, hominy, and many other items.

Etymology

[edit]In the Aztec language Nahuatl, the word for the product of this procedure is nixtamalli or nextamalli (pronounced [niʃtaˈmalːi] or [neʃtaˈmalːi]), which in turn has yielded Mexican Spanish nixtamal ([nistaˈmal]). The Nahuatl word is a compound of nextli "lime ashes" and tamalli "unformed/cooked corn dough, tamal".[6] The term nixtamalization can also be used to describe the removal of the pericarp from any grain by an alkali process, including maize, sorghum, and others. When the unaltered Spanish spelling nixtamalización is used in written English, however, it almost exclusively refers to maize.

The labels on packages of commercially sold tortillas prepared with nixtamalized maize usually list corn treated with lime as an ingredient in English, while the Spanish versions list maíz nixtamalizado.

History

[edit]Mesoamerica

[edit]

The process of nixtamalization was first developed in Mesoamerica, where maize was originally cultivated. There is no precise date when the technology was developed, but the earliest evidence of nixtamalization is found in Guatemala's southern coast, with equipment dating from 1200 to 1500 BC.[7]

How nixtamalization was discovered is not known, but one possibility may have been through the use of hot stones (see pot boiler) to boil corn in early cultures which did not have cooking vessels robust enough to put directly on fire or coals. In limestone regions like those in Guatemala and southern Mexico, heated chunks of limestone would naturally be used, and experiments show that hot limestone makes the cooking water sufficiently alkaline to cause nixtamalization. Archaeological evidence supporting this possibility has been found in southern Utah, United States.[8]

The Aztec and Mayan civilizations developed nixtamalization using slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and lye (potassium hydroxide) to create alkaline solutions. The Chibcha people to the north of the ancient Inca also used calcium hydroxide (also known as "cal"), while the tribes of North America used soda ash.

The nixtamalization process was very important in the early Mesoamerican diet, as there is very little niacin in corn and the tryptophan within is unavailable without processing.[4]: §5.2 A population that depends on untreated maize as a staple food risks malnourishment and is more likely to develop deficiency diseases such as pellagra, niacin deficiency, or kwashiorkor, the absence of certain amino acids that maize is deficient in. Maize cooked with lime or other alkali provided bioavailable niacin to Mesoamericans. Beans provided the otherwise missing amino acids required to balance maize for complete protein.[4]: §8

Spread

[edit]The spread of maize cultivation in the Americas was accompanied by the adoption of the nixtamalization process. Traditional and contemporary regional cuisines (including Maya cuisine, Aztec cuisine, and Mexican cuisine) included, and still include, foods based on nixtamalized maize.

The process has not substantially declined in usage in the Mesoamerican region, though there has been a decline in North America. Many Native North American tribes, such as the Huron, no longer use the process.[citation needed] In some Mesoamerican and North American regions, dishes are still made from nixtamalized maize prepared by traditional techniques. The Hopi produce sodium carbonate from ashes of various native plants and trees.[9][10] Some contemporary Maya use calcium salts in the form of ashes of burnt mussel shells or heated limestone.[11]

In the United States, European settlers did not always adopt the nixtamalization process, except in the case of hominy grits, though maize became a staple among the poor of the southern states. This led to endemic pellagra in poor populations throughout the southern US in the early 20th century.[12] A more varied diet and fortification of wheat flour, the other staple food, have essentially eliminated this deficiency.[13]

Process

[edit]Cooking

[edit]

In the first step of nixtamalization, kernels of dried maize are cooked in an alkaline solution at or near the mixture's boiling point. After cooking, the maize is steeped in the cooking liquid for a period. The length of time for which the maize is boiled and soaked varies according to local traditions and the type of food being prepared, with cooking times ranging from a few minutes to an hour, and soaking times from a few minutes to about a day.

During cooking and soaking, a number of chemical changes take place in the grains of maize. Because plant cell wall components, including hemicellulose and pectin, are highly soluble in alkaline solutions, the kernels soften and their pericarps (hulls) loosen. The grain hydrates and absorbs calcium or potassium (depending on the alkali used) from the cooking solution. Starches swell and gelatinize, and some starches disperse into the liquid. Certain chemicals[which?] from the germ are released that allow the cooked grains to be ground more easily, yet make dough made from the grains less likely to tear and break down. Cooking changes the grain's protein matrix, which makes proteins and nutrients from the endosperm of the kernel more available to the human body.

Extraction

[edit]After cooking, the alkaline liquid (known as nejayote), containing dissolved hull, starch, and other corn matter, is decanted and discarded (or sometimes used for making amate bark paper).[14] The kernels are washed thoroughly of remaining nejayote, which has an unpleasant flavor. The pericarp is then removed, leaving the endosperm of the grain with or without the germ, depending on the process.[15][16][17][18][19] This hulling is performed by hand, in traditional or very small-scale preparation, or mechanically, in larger scale or industrial production.

The prepared grain is called hominy or nixtamal. Nixtamal has many uses, contemporary and historic. Whole nixtamal may be used fresh or dried for later use. Whole nixtamal is used in the preparation of pozole, menudo, and other foods. Ground fresh nixtamal is made into masa (nixtamal dough) and used to make tortillas, tamales, and pupusas. Dried and ground, it is called masa harina or instant masa flour, and is reconstituted and used like masa.

The term hominy may refer to whole, coarsely ground, or finely ground nixtamal, or to a cooked porridge (also called samp) prepared from any of these.

Enzymatic nixtamalization

[edit]An alternative process for use in industrial settings has been developed known as enzymatic nixtamalization, which uses protease enzymes to accelerate the changes that occur in traditional nixtamalization, a technique borrowed from modern corn wet-milling. In this process, corn or corn meal is first partially hydrated in hot water, so that enzymes can penetrate the grain, then soaked briefly (for approximately 30 minutes) at 50–60 °C (122–140 °F) in an alkaline solution containing protease enzymes. A secondary enzymatic digestion may follow to further dissolve the pericarp. The resulting nixtamal is ground with little or no washing or hulling.

By pre-soaking the maize, minimizing the alkali used to adjust the pH of the alkaline solution, reducing the cooking temperature, accelerating processing, and reusing excess processing liquids, enzymatic nixtamalization can reduce the use of energy and water, lower nejayote (alkaline wastewater) production, decrease maize lost in processing, and shorten the production time (to approximately four hours) compared to traditional nixtamalization.[20]

Impact on health

[edit]The primary nutritional benefits of nixtamalization arise from the alkaline processing involved. The processing renders the protein more digestible, allowing tryptophan to be absorbed by humans. Humans can convert tryptophan into niacin, thus helping to prevent pellagra. Other measures of protein quality are also improved.[4]: §5.2 It was originally thought that the anti-pellagra action stems from increased availability of niacin (compared to a hemicellulose-bound form called "niacytin"),[3] but multiple experiments have disproven this theory.[4]: §5.2

Secondary benefits can arise from the grain's absorption of minerals from the alkali used or from the vessels used in preparation. These effects can increase calcium (by 750%, with 85% available for absorption), iron, copper, and zinc.[3]

Nixtamalization significantly deactivates (by 90–94%) mycotoxins produced by Fusarium verticillioides and Fusarium proliferatum, molds that commonly infect maize, the toxins of which are putative carcinogens.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Thigpen, Susan (October 1983). "Hominy – Mountain Recipe". The Mountain Laurel. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ Doralinda Guzmán-de-Peña (2010). "The Destruction of Aflatoxins in Corn by "Nixtamalización"" (PDF). In M. Rai; A. Varma (eds.). Mycotoxins in Food, Feed and Bioweapons. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. pp. 39–49. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-00725-5_3. ISBN 978-3-642-00724-8. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Wacher, Carmen (January 1, 2003). "Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology to process maize at small-scale with great potential for improving the nutritional quality of maize based foods". Food Based Approaches for a Healthy Nutrition in Africa. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Maize in human nutrition. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1992. ISBN 9789251030134. – Section 5.2 "Lime-treated maize (part II)", Section 8 "Improvement of maize diets"

- ^ Harold McGee (2004). On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen. New York, New York (USA): Scribner. p. 478. ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Días Roig, Mercedes; Miaja, María Teresa (1979). Naranja dulce, limón partido (in Spanish) (1st ed.). México City: El Colegio de México. p. 137. ISBN 968-12-0049-7.

- ^ Staller, John E.; Carrasco, Michael (2009). Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 317. ISBN 978-1-4419-0471-3.

- ^ Ellwood, Emily C.; Scott, M. Paul; Lipe, William D.; Matson, R.G.; Jones, John G. (2013). "Stone-boiling maize with limestone: experimental results and implications for nutrition among SE Utah preceramic groups". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (1): 35–44. Bibcode:2013JArSc..40...35E. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.05.044.

- ^ Jennie Rose Joe; Robert S. Young (1993). Diabetes As a Disease of Civilization: The Impact of Culture Change on Indigenous People. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013474-2. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ Linda Murray Berzok (2005). American Indian Food. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32989-0. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ "Guatemalan Tortillas: How To Make Them And Why To Eat Them". Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Latham, Michael C. (1997). Human Nutrition in the Developing World. Food & Agriculture Org. p. 183. ISBN 9789251038185.

- ^ Rucker, Robert B.; Zempleni, Janos; Suttie, John W.; Donald B. McCormick (2010). Handbook of Vitamins, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-4200-0580-6.

- ^ von Hagen, Victor Wolfgang (1944). The Aztec and Maya Papermakers. J. J. Augustin Publisher. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-87817-206-1.

- ^ "What is Hominy?". Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Nixtamalization, a Mesoamerican technology". Retrieved January 31, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Technological Limitations of the Nixtamalization Process". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Selective Nixtamalization of Fractions of Maize Grain". Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "What's the difference between corn meal and corn masa?". November 4, 2010. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ US patent 6428828, Jackson, David S. & Sahai, Deepak, "Enzymatic process for nixtamalization of cereal grains", issued 2002-08-06, assigned to NuTech Ventures Inc

- Coe, Sophie. America's First Cuisines (1994). ISBN 0-292-71159-X

- Davidson, Alan. Oxford Companion to Food (1999), "Nixtamalization", p. 534. ISBN 0-19-211579-0

- Kulp, Karen and Klaude J. Lorenz (editors). Handbook of Cereal Science and Technology (2000), p. 670. ISBN 0-8247-8358-1

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking, 2nd Edition (2004) p. 477-478 ISBN 0-684-80001-2

- Smith, C. Wayne, Javier Betrán and E. C. A. Runge (editors). Corn: Origins, History and Technology (2004) p. 275 ISBN 0-471-41184-1