Cimarron (1960 film): Difference between revisions

Tag: Reverted |

m Remove template per TFD outcome |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|1960 film}} |

{{Short description|1960 film by Anthony Mann}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2021}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=October 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox film |

{{Infobox film |

||

| name = Cimarron |

| name = Cimarron |

||

| image = Cimarron1960.jpg |

| image = Cimarron1960.jpg |

||

| caption = |

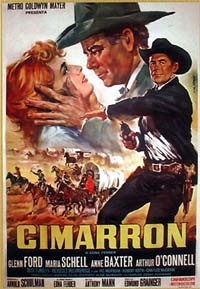

| caption = Theatrical release poster |

||

| director = [[Anthony Mann]] |

| director = [[Anthony Mann]]{{efn|During the middle of filming, Mann left the project and was replaced by [[Charles Walters]] who was uncredited.<ref name="TurnerClassicMovies" />}} |

||

| producer = [[Edmund Grainger]] |

| producer = [[Edmund Grainger]] |

||

| based_on = {{based on|''[[Cimarron (novel)|Cimarron]]''<br> |

| based_on = {{based on|''[[Cimarron (novel)|Cimarron]]''<br>1930 novel|[[Edna Ferber]]}} |

||

| screenplay = [[Arnold Schulman]] |

| screenplay = [[Arnold Schulman]] |

||

| narrator = |

|||

| starring = [[Glenn Ford]]<br />[[Maria Schell]]<br />[[Anne Baxter]]<br />[[Harry Morgan]] |

| starring = [[Glenn Ford]]<br />[[Maria Schell]]<br />[[Anne Baxter]]<br />[[Harry Morgan]] |

||

| music = [[Franz Waxman]] |

| music = [[Franz Waxman]] |

||

| Line 14: | Line 15: | ||

| editing = [[John Dunning (film editor)|John D. Dunning]] |

| editing = [[John Dunning (film editor)|John D. Dunning]] |

||

| distributor = [[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer]] |

| distributor = [[Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer]] |

||

| released = |

| released = {{Film date|1960|12|1|premiere}} |

||

| runtime = 147 minutes |

| runtime = 147 minutes |

||

| country = United States |

| country = United States |

||

| language = English |

| language = English |

||

| budget = $5,421,000<ref name="Mannix">{{ |

| budget = $5,421,000<ref name="Mannix">{{cite book |author=Mannix, Eddie |author-link=Eddie Mannix |title=The Eddie Mannix Ledger |year=1962 |location=[[Margaret Herrick Library]] |oclc=801258228}}{{Page needed|date=January 2022}}</ref> |

||

| gross = $4,825,000<ref name="Mannix"/> |

| gross = $4,825,000<ref name="Mannix"/> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Cimarron''''' is a 1960 American [[List of Western subgenres#Epic Western|epic Western]] film based on the 1930 [[Edna Ferber]] novel ''[[Cimarron (novel)|Cimarron]]''. The film stars [[Glenn Ford]] and [[Maria Schell]] and was directed by [[Anthony Mann]] and Charles Walters, though Walters is not credited onscreen.<ref name="TurnerClassicMovies">{{Cite web |last=Tatara |first=Paul |url=https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/14909/cimarron#articles-reviews?articleId=99252 |title=Cimarron (1960) |access-date=2019-12-15 |website=Turner Classic Movies |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210523094726/https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/14909/cimarron/#overview |archive-date=2021-05-23}}</ref> Ferber's novel was previously adapted as a film in 1931; [[Cimarron (1931 film)|that version]] won three [[Academy Awards]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | ''Cimarron'' was the first of three epics (along with ''[[El Cid (film)|El Cid]]'' and ''[[The Fall of the Roman Empire (film)|The Fall of the Roman Empire]]'') that Mann directed. Despite high production costs and an experienced cast of Western veterans, stage actors and future stars, the film was released with little fanfare. |

||

'''''Cimarron''''' is a 1960 [[Metrocolor]] [[Western (genre)|western film]] filmed in [[CinemaScope]], based on the [[Edna Ferber]] novel ''[[Cimarron (novel)|Cimarron]]'', featuring [[Glenn Ford]] and [[Maria Schell]]. It was directed by [[Anthony Mann]], known for his westerns and [[film noir]]s, and by Charles Walters, who was not credited.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

Ferber's novel was previously adapted in 1931; [[Cimarron (1931 film)|that version]] won three [[Academy Awards]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | ''Cimarron'' was the first of three epics ( |

||

==Plot== |

==Plot== |

||

| ⚫ | Sabra Cravat joins her new husband, lawyer Yancey "Cimarron" Cravat, during the [[Land Rush of 1889|Oklahoma land rush of 1889]]. They encounter Yancey's old friend William "The Kid" Hardy and his buddies Wes Jennings and Hoss Barry. On the trail, Yancey helps Tom and Sarah Wyatt and their eight children, taking them aboard their wagons. |

||

{{Long plot|section|date=December 2019}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

At the jump off point, it seems to Sabra that her husband knows everyone in Oklahoma, from Ned the cavalry officer to dance hall girl Dixie Lee ([[Anne Baxter]]). A small crowd cheers Bob Yountis ([[Charles McGraw]]) and his henchman Millis ([[L. Q. Jones]]) when they attack a Native American family, whipping Arita Redfeather (Dawn Little Sky), her baby in her arms, overturning their wagon and beating her husband, Ben (Eddie Little Sky). Yancey joins his friend Sam Pegler ([[Robert Keith (actor)|Robert Keith]]) in fighting them off. |

|||

When a Cavalry officer confirms that the couple have a right to be there, the crowd disperses. Yountis threatens Pegler, a newspaper editor, if he tries the same crusading here that he did in Texas. Sabra is angry that Yancey risked his life for an Indian—and is chastened at the icy reactions to this remark. She steps forward to join the others, including peddler Sol Levy ([[David Opatoshu]]) and printer Jess Rickey ([[Harry Morgan]]) in righting the wagon. |

|||

That night Sam and his wife, Mavis ([[Aline MacMahon]]), reveal more about Yancey's past as a cowboy, a gambler, a gunman, and a lawyer. They scoff at his being a rancher. They hope to pass the legacy of the paper on to him. |

|||

It seems to Sabra that her husband knows everyone in Oklahoma. A small crowd cheers Bob Yountis and his henchman Millis when they attack an Indian family. Yancey joins his friend Sam Pegler, editor of the ''Oklahoma Wigwam'' newspaper, in resisting Yountis. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Yountis warns Pegler against using the paper for his crusading as he had done in Texas. Sabra is angry that Yancey risked his life for an Indian but she helps the others, including peddler Sol Levy and printer Jesse Rickey, in righting the Indians' overturned wagon. Sam and his wife Mavis reveal more about Yancey's past as a cowboy, gambler, gunman and lawyer. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Four years later, Osage is thriving. |

||

| ⚫ | In the new town of Osage, which consists of tents and half-built storefronts, Yountis and The Kid terrorize Levy in the street. Yancey tries but fails to persuade the Kid to change. One night, Yountis leads a lynch mob against the Indian family. Yancey arrives too late to stop it, but he kills Yountis and brings Arita and her baby Ruby home. Meanwhile, Sabra gives birth to a boy whom they name Cimarron, Cim for short. |

||

Yancey is ecstatic when a [[News agency|news service]] telegram announces the opening of the [[Land Run of 1893|Cherokee Strip]]. He tells Sabra: They are going. She says No. He goes. Five years later, Tom is still working on his oil well. A duffel bag arrives from Yancey, from Alaska, with nothing in it but a polar bear skin. Yancey joins [[Theodore Roosevelt|Roosevelt]] in [[Cuba]] and eventually "Osage's Own [[Rough Riders|Rough Rider]]" returns. Sabra—who was planning to scold him—runs into his arms. Cim also forgives him. |

|||

| ⚫ | Four years later, Osage is thriving. Tom has built an [[Oil well|oil-drilling apparatus]] but he is a laughingstock. Wes, Hoss and The Kid, wanted outlaws, try to rob a train but are all killed soon after. When Yancey destroys the $1,000 reward check, Sabra is furious because he does not consider their son's security. Yancey leaves to be part of the [[Land Run of 1893|Cherokee Strip]], but Sabra refuses to join him. Years later, he returns and Sabra and Cim forgive him. |

||

Then Tom bursts in, covered in oil. |

|||

Tom finally strikes oil, but Yancey is disgusted to learn that Tom bought the [[Mineral rights|rights]] to oil found on Indian land. However, Yancey's campaign to win the Indians justice is a huge success, and he is invited to become governor of the [[Oklahoma Territory]]. Sabra is disappointed to discover that Cim and Ruby have grown close. |

|||

In [[Washington, D. C. |

In [[Washington, D. C.|Washington, D.C.]], Yancey finds Tom with a group of influential men and learns that the price of his appointment is his integrity. When Yancy tells Sabra that he can't be governor, she sends him away forever. |

||

Cim and Ruby marry |

Cim and Ruby marry without warning and set off for Oregon, though Sabra tells him that he is throwing his life away. |

||

Ten years later, on the occasion of the ''Oklahoma Wigwam''<nowiki/>'s 25th anniversary, the United States’ entry into [[World War I]] is announced. Later, Sabra hears that Yancey has been killed in the war. |

|||

Ten years later, it is the Oklahoma Wigwam's 25th anniversary. Sol and Tom want Sabra to pose for a statue representing the Oklahoma pioneer. She refuses. There is a surprise party, and Cim, Ruby and their two children are there, as is Mavis Pegler. Sabra talks about Yancey. The phone rings: [[World War I|War]] has been declared. In December, she reads a letter from him. On the table is a telegram from the [[War Office|British War Office]] notifying her of his death in action. She remembers their years together, and the camera zooms in on the finished statue: It is Yancey. |

|||

==Cast== |

==Cast== |

||

{{columns-list|colwidth=35em| |

|||

===Main=== |

|||

* [[Glenn Ford]] as Yancey Cravat |

* [[Glenn Ford]] as Yancey Cravat |

||

* [[Maria Schell]] as Sabra Cravat |

* [[Maria Schell]] as Sabra Cravat |

||

* [[Anne Baxter]] as Dixie Lee |

* [[Anne Baxter]] as Dixie Lee |

||

* [[Arthur O'Connell]] as Tom Wyatt |

* [[Arthur O'Connell]] as Tom Wyatt |

||

* [[Russ Tamblyn]] as William Hardy |

* [[Russ Tamblyn]] as William Hardy / The Cherokee Kid |

||

* [[Mercedes McCambridge]] as Sarah Wyatt |

* [[Mercedes McCambridge]] as Sarah Wyatt |

||

* [[Vic Morrow]] as Wes Jennings |

* [[Vic Morrow]] as Wes Jennings |

||

| Line 68: | Line 59: | ||

* [[Charles McGraw]] as Bob Yountis |

* [[Charles McGraw]] as Bob Yountis |

||

* [[Aline MacMahon]] as Mavis Pegler |

* [[Aline MacMahon]] as Mavis Pegler |

||

* [[Harry Morgan]] as Jesse Rickey (Credited as Henry |

* [[Harry Morgan]] as Jesse Rickey (Credited as Henry "Harry" Morgan) |

||

* [[David Opatoshu]] as Sol Levy |

* [[David Opatoshu]] as Sol Levy |

||

* [[Edgar Buchanan]] as Judge Neal Hefner |

* [[Edgar Buchanan]] as Judge Neal Hefner |

||

===Supporting=== |

|||

* [[Lili Darvas]] as Felicia Venable |

* [[Lili Darvas]] as Felicia Venable |

||

* [[Mary Wickes]] as Mrs. Neal Hefner |

* [[Mary Wickes]] as Mrs. Neal Hefner |

||

* [[Royal Dano]] as Ike Howes |

* [[Royal Dano]] as Ike Howes |

||

* [[L. Q. Jones]] as Millis |

* [[L. Q. Jones]] as Millis |

||

* George Brenlin as Hoss Barry |

* [[George Brenlin]] as Hoss Barry |

||

* [[Vladimir Sokoloff]] as Jacob Krubeckoff |

* [[Vladimir Sokoloff]] as Jacob Krubeckoff |

||

* [[Eugene Jackson]] as Isaiah |

* [[Eugene Jackson]] as Isaiah |

||

}} |

|||

; Uncredited |

|||

{{columns-list|colwidth=35em| |

|||

{{div col}} |

|||

* Andy Albin as Water Man |

* Andy Albin as Water Man |

||

* [[Rayford Barnes]] as Cavalry Sergeant Who Breaks Up Fight |

* [[Rayford Barnes]] as Cavalry Sergeant Who Breaks Up Fight |

||

* Herman Belmonte as Dancer |

* Herman Belmonte as Dancer At Ball |

||

* Mary Benoit as Mrs. Lancey |

* Mary Benoit as Mrs. Lancey |

||

* Barry Bernard as Butler |

* Barry Bernard as Butler |

||

| Line 92: | Line 82: | ||

* [[Chet Brandenburg]] as Townsman |

* [[Chet Brandenburg]] as Townsman |

||

* Janet Brandt as Madam Rhoda |

* Janet Brandt as Madam Rhoda |

||

* [[Paul Bryar]] as Mr. Self |

* [[Paul Bryar]] as Mr. Self, Politician |

||

* [[Robert Carson (actor)|Robert Carson]] as Senator Rollins |

* [[Robert Carson (actor)|Robert Carson]] as Senator Rollins |

||

* [[John L. Cason]] as Suggs |

* [[John L. Cason]] as Suggs |

||

* [[William Challee]] as Barber |

* [[William Challee]] as The Barber |

||

* Mickie Chouteau as Ruby Red Feather |

* Mickie Chouteau as Ruby Red Feather |

||

* Fred Coby as Oil Worker |

* [[Fred Coby]] as Oil Worker |

||

* Gene Coogan as Butler / Townsman |

* Gene Coogan as Butler / Townsman |

||

* Jack Daly as Wyatt's Man |

* Jack Daly as Wyatt's Man |

||

* John Damler as Foreman |

* John Damler as Foreman |

||

* [[Richard Davies (American actor)|Richard Davies]] as Mr. Hodges |

* [[Richard Davies (American actor)|Richard Davies]] as Mr. Hodges |

||

* [[George DeNormand]] as Townsman |

* [[George DeNormand]] as Townsman At Celebration |

||

* [[James Dime]] as Townsman |

* [[James Dime]] as Townsman |

||

* [[Phyllis Douglas]] as Sadie |

* [[Phyllis Douglas]] as Sadie |

||

* [[Ted Eccles]] as Cimarron Cravat – Age 2 |

* [[Ted Eccles]] as Cimarron Cravat – Age 2 |

||

* LaRue Farlow as Dancer |

* LaRue Farlow as Dancer |

||

* [[Franklyn Farnum]] as Townsman |

* [[Franklyn Farnum]] as Townsman At Schoolhouse |

||

* George Ford as Townsman |

* George Ford as Townsman At Celebration |

||

* [[Coleman Francis]] as Mr. Geer |

* [[Coleman Francis]] as Mr. Geer |

||

* Ben Gary as Reporter |

* Ben Gary as Reporter |

||

* James Halferty as Cimarron Cravat – Age 10 |

* James Halferty as Cimarron Cravat – Age 10 |

||

* Sam Harris as Ball Guest |

* Sam Harris as Ball Guest |

||

* Lars Hensen as Dancer |

* Lars Hensen as Dancer At Ball |

||

* [[Clegg Hoyt]] as Great Gotch |

* [[Clegg Hoyt]] as "Great" Gotch |

||

* [[Irene James]] as Townswoman |

* [[Irene James]] as Townswoman |

||

* [[Colin Kenny (actor)|Colin Kenny]] as Townsman |

* [[Colin Kenny (actor)|Colin Kenny]] as Townsman At Schoolhouse |

||

* Paul Kruger as Party Guest |

* Paul Kruger as Party Guest |

||

* [[Jimmy Lewis (musician)|Jimmy Lewis]] as Hefner Boy |

* [[Jimmy Lewis (musician)|Jimmy Lewis]] as Hefner Boy |

||

* Dawn Little Sky as Arita Red Feather |

* Dawn Little Sky as Arita Red Feather |

||

* [[Eddie Little Sky]] as Ben Red Feather |

* [[Eddie Little Sky]] as Ben Red Feather |

||

* Buzz Martin as Cimarron Cravat as |

* Buzz Martin as Cimarron Cravat as Young Man |

||

* [[Kermit Maynard]] as Setter |

* [[Kermit Maynard]] as Setter |

||

* Mathew McCue as Townsman |

* Mathew McCue as Townsman |

||

| Line 127: | Line 117: | ||

* Walter Merrill as Reporter |

* Walter Merrill as Reporter |

||

* [[Jack Perry (clown)|Jack Perry]] as Townsman |

* [[Jack Perry (clown)|Jack Perry]] as Townsman |

||

* [[John Pickard (American actor)|John Pickard]] as Ned |

* [[John Pickard (American actor)|John Pickard]] as Ned, Cavalry Captain |

||

* Ralph Reed as Bellboy |

* Ralph Reed as Bellboy |

||

* William Remick as Reporter |

* William Remick as Reporter |

||

| Line 133: | Line 123: | ||

* Jack Scroggy as Walter |

* Jack Scroggy as Walter |

||

* [[Charles Seel]] as Charles |

* [[Charles Seel]] as Charles |

||

* Bernard Sell as Townsman |

* Bernard Sell as Townsman At Celebration |

||

* Jack Stoney as Man |

* Jack Stoney as Man At Lynching |

||

* [[Harry Tenbrook]] as Sooner |

* [[Harry Tenbrook]] as Sooner At Camp Fight |

||

* Arthur Tovey as Dancer |

* [[Arthur Tovey]] as Dancer At Ball |

||

* [[Ivan Triesault]] as Lewis Venable |

* [[Ivan Triesault]] as Lewis Venable, Sabra's Father |

||

* [[Charlie Watts|Charles Watts]] as Lou Brothers |

* [[Charlie Watts|Charles Watts]] as Lou Brothers, Politician |

||

* [[Helen Westcott]] as Miss Kuye |

* [[Helen Westcott]] as Miss Kuye, Schoolteacher |

||

* [[Robert B. Williams (actor)|Robert Williams]] as Oil Worker |

* [[Robert B. Williams (actor)|Robert Williams]] as Oil Worker |

||

* Jeane Wood as Clubwoman |

* Jeane Wood as Clubwoman |

||

* [[Wilson Wood (actor)|Wilson Wood]] as Reporter |

* [[Wilson Wood (actor)|Wilson Wood]] as Reporter |

||

* Jorie Wyler as Theresa Jump |

* Jorie Wyler as Theresa Jump |

||

}} |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

==Production== |

==Production== |

||

In February 1941, MGM bought the remake rights to ''Cimarron'' from RKO for $100,000.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Metro Buys 'Cimarron' Rights From RKO for $100,000|date=February 22, 1941|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1941/02/22/archives/metro-buys-cimarron-rights-from-rko-for-100000-purchases-rio-rita.html|work=The New York Times|page=11|url-access=subscription}}</ref> In 1947, MGM announced an [[operetta]] version starring [[Kathryn Grayson]] and produced by [[Arthur Freed]],<ref>{{Cite news|last=Brady|first=Thomas F.|title='Cimarron' Remake Listed by Metro|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1947/11/24/archives/cimarron-remake-listed-by-metro-arthur-freed-to-produce-new-film-of.html|date=November 24, 1947|work=The New York Times|page=30|url-access=subscription}}</ref> but this did not happen. In February 1958, MGM announced its plans to produce ''Cimarron'' as the studio's second film using the [[Ultra Panavision 70|MGM Camera 65]] process following ''[[Raintree County (film)|Raintree Country]]'' (1957).<ref>{{cite magazine|magazine=[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]|title=Metro Remakes 'Cimarron'|date=February 26, 1958|page=20|url=https://archive.org/details/variety209-1958-02/page/n243/mode/1up|access-date=September 28, 2021|via=[[Internet Archive]]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|title=U.S. vs. Al Capone To Be Film Theme|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1958/02/20/archives/u-s-vs-al-capone-to-be-film-theme-story-of-treasury-agents-war-on.html|first=Thomas M.|last=Pryor|date=February 20, 1958|work=The New York Times|page=29|url-access=subscription}}</ref> One month later, [[Elizabeth Taylor]] and [[Rock Hudson]] were considered to star in the film.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=41 Westerns On Hoof in 1958|magazine=Variety|page=4|date=March 5, 1958|url=https://archive.org/details/variety210-1958-03/page/n13/mode/2up|access-date=January 4, 2022|via=Internet Archive}}</ref> Ultimately, [[Glenn Ford]], who previously starred in the Westerns such as ''[[3:10 to Yuma (1957 film)|3:10 to Yuma]]'' (1957) and ''[[The Sheepman]]'' (1958), was attached to star.<ref>{{cite news|title=Glenn Ford Value Seen as 'Built' Star: Ava Gardner His Likely Lead; Producer Cites Other Examples|author=Scheuer, Philip K.|newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]|date=February 17, 1959|page=C7}}</ref> In October 1959, [[Arnold Schulman]] was signed to write the screenplay.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1959/10/08/archives/schulman-forms-production-unit-author-of-a-hole-in-the-head-plans.html|title=Schulman Forms Production Unit|work=The New York Times|page=49|date=October 8, 1959|url-access=subscription}}</ref> For his script, Schulman introduced several characters, including those of journalist Sam Pegler ([[Robert Keith (actor)|Robert Keith]]) and Wes Jennings ([[Vic Morrow]]), while removing the Cravats' daughter, Donna and a boy named Isaiah.<ref name="TurnerClassicMovies" /> [[King Vidor]] declined an invitation to direct.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Entertainment Films Stage Music: Viertel Film Will Not Star Deborah|date=September 11, 1959|work=Los Angeles Times|page=B6}}</ref> |

|||

MGM bought the remake rights from RKO in 1941 for $100,000.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Metro Buys 'Cimarron' Rights From RKO for $100,000 – Purchases 'Rio Rita': BRITISH FILM HERE TODAY "It Happened to One Man' Opens at Carnegie – 'Tobacco Road' Sets First Day Record|date=Feb 22, 1941|work=New York Times|page=11}}</ref> |

|||

In 1947 it was announced they would make an [[operetta]] version starring [[Kathryn Grayson]] and produced by [[Arthur Freed]].<ref>{{Cite news|title=CIMARRON' REMAKE LISTED BY METRO: Arthur Freed to Produce New Film of Edna Ferber Novel, Starring Kathryn Grayson|author=THOMAS F. BRADY|date=Nov 24, 1947|work=New York Times|page=30}}</ref> However, this did not happen. |

|||

MGM announced further plans to make it in February 1958.<ref>{{Cite news|title=U. S. VS. AL CAPONE TO BE FILM THEME: Story of Treasury Agents' War on Breweries Slated -Holden-Paramount Rift|author=THOMAS M. PRYOR|date=Feb 20, 1958|work=New York Times|page=29}}</ref> The handsome trending actor Glenn Ford, having experience in western films ''[[3:10 to Yuma (1957 film)|3:10 to Yuma (1957)]]'' and ''[[The Sheepman|The Sheepman (1958)]]'', soon became attached as star.<ref>{{cite news|title=Glenn Ford Value Seen as 'Built' Star: Ava Gardner His Likely Lead; Producer Cites Other Examples|author=Scheuer, Philip K.|work=Los Angeles Times|date=Feb 17, 1959|page=C7}}</ref> |

|||

[[Anthony Mann]] was eventually named as director. He had pitched to his vision to MGM executives, explaining: "I wanted to show a huge plain out in the West with nothing on it, and how a group of men and women gathered at a line, and tore out across this plain and set up their stakes as claim for the land. And how a town, a city and finally a metropolis grew, all on this one piece of land."<ref name="mann">{{cite magazine|title=Interviews with Anthony Mann|magazine=Screen|volume=10|date=July–October 1969| first1=Christopher|first2=Barrie|last2=Pattinson|last1=Wicking|url=https://archive.org/details/Screen_Volume_10_Issue_4-5/page/n31/mode/2up|pages=44–45}}</ref> Principal photography was shot in Arizona, most particularly the depiction of the [[Land Rush of 1889|Oklahoma Land Rush]],<ref>{{Cite news |last=Rothwell |first=John H. |title=Shot on the Old 'Cimarron' Trail |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1960/01/10/archives/shot-on-the-old-cimarron-trail.html |work=The New York Times |date=January 10, 1960 |page=X7 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> which featured over 1,000 extras, 700 horses and 500 wagons and buggies.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Cimarron (1960)—AFI Catalog of Feature Films |url=https://catalog.afi.com/Film/53484-CIMARRON?sid=72b2360b-c55e-4dd7-b454-2600b1357870&sr=12.106492&cp=1&pos=0 |access-date=2024-06-16 |website=[[AFI Catalog of Feature Films]] |publisher=[[American Film Institute]]}}</ref> |

|||

[[King Vidor]] turned down the chance to direct.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Entertainment Films Stage Music: Viertel Film Will Not Star Deborah|date=Sep 11, 1959|work=Los Angeles Times|page=B6}}</ref> [[Arnold Schulman]] was signed to write the screenplay.<ref>{{Cite news|title=SCHULMAN FORMS PRODUCTION UNIT: Author of 'A Hole in the Head' Plans Second Play for Stage and Films|date=Oct 8, 1959|work=New York Times|page=49}}</ref> Anthony Mann was eventually chosen to direct the reimagining of the 1931 classic. Most known for the critically acclaimed hits ''[[The Glenn Miller Story|The Glenn Miller Story (1954)]]'' and ''[[Men in War|Men in War (1957)]]'', Mann had proven himself as a talented western director in the decade prior to ''Cimarron'', contributing eight films to the genre.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0542649/|title=Anthony Mann|website=IMDb|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref> However, disagreements in the direction of the film ''Cimarron'' led to bitter arguments with producer [[Edmund Grainger]], until eventually Mann left the project halfway through filming. Director [[Charles Walters]] finished the film but received no screen credit.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/99252%7C0/Cimarron.html|title=Cimarron (1960)|website=Turner Classic Movies|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref> |

|||

As production continued, the on-location shoot experienced [[dust storm]]s, in which producer [[Edmund Grainger]] decided to relocate the production on the studio backlot despite Mann's insistence to film entirely on location.{{sfn|Bassinger|2007|p=[https://archive.org/details/anthonymann00basi/page/146/mode/2up 146]}} Mann explained: "We had a couple of storms—which I shot in anyway—but they thought we'd have floods and so on, so they dragged us in and everything had to be duplicated on the set. The story had to be changed, because we couldn't do the things we wanted to. So I don't consider it a film. I just consider it a disaster."<ref name="mann" /> Mann left the production, and director [[Charles Walters]] finished the film but received no screen credit.<ref name="TurnerClassicMovies" /> Mann was also critical of the film's final cut, explaining that Ford was meant to die on screen. Years later, he explained: "There was a huge oil sequence and oil wells were blowing up and he was saving people and being very heroic. Why they ever changed it I'll never know – this was Mr. [[Sol Siegel]], he did it behind my back, I didn't ever see it. If I'd screamed they wouldn't have bothered anyway; so I just let them destroy it at will."<ref name="mann"/> |

|||

The climactic scene portraying the Oklahoma Land Rush was shot in Arizona<ref>{{Cite news|title=SHOT ON THE OLD 'CIMARRON' TRAIL|author=JOHN H. ROTHWELL|date=Jan 10, 1960|work=New York Times|page=X7}}</ref> and featured over 1000 extras, 700 horses, and 500 wagons and buggies.<ref>{{Citation|title=Cimarron (1960)|url=http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0053715/trivia|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref> |

|||

[[Anne Baxter]], who |

Also, during filming, [[Anne Baxter]], who played Dixie Lee, revealed in her autobiography ''Intermission'' that Ford and Maria Schell developed an offscreen romance: "During shooting, they'd scrambled together like eggs. I understood she'd even begun divorce proceedings in Germany. It was obviously premature of her." However, by the end of filming, "... he scarcely glanced or spoke in her direction, and she looked as if she were in shock."{{sfn|Baxter|1976|p=[https://archive.org/details/isbn_399115773/page/196/mode/2up 196]}} |

||

==Reception== |

==Reception== |

||

===Box office=== |

|||

According to MGM records, |

According to MGM records, ''Cimarron'' earned $2,325,000 in the U.S. and Canada and $2,500,000 overseas, resulting in an overall loss of $3,618,000.<ref name="Mannix"/> |

||

===Critical reaction=== |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1961, the film was nominated for [[Academy Award for Best Production Design|Best Art Direction]] ([[George Davis (art director)|George W. Davis]], [[Addison Hehr]], [[Henry Grace]], [[Hugh Hunt]] |

||

''[[Harrison's Reports]]'' wrote: "The background music is undistinguished. There's enough marquee strength, action, romance, and the 'land rush' scene at the beginning is worth the price of a soft ticket. Color photography is outstanding."<ref>{{cite magazine |title='Cimarron' with Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, Anne Baxter |url=https://archive.org/details/harrisonsreports42harr/page/198/mode/2up |magazine=Harrison's Reports |page=198 |date=December 10, 1960 |access-date=January 4, 2022 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref> Thomas M. Pryor, reviewing for ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'', praised Schell and Ford's performances, and wrote "Although ''Cimarron'' is not without flaws—thoughtful examination reveals a pretentiousness of social significance more than valid exposition—the script plays well."<ref>{{cite news |url=https://archive.org/details/variety221-1960-12 |title=Film Reviews: Cimarron |work=Variety |page=6 |date=December 7, 1960 |access-date=January 4, 2022 |via=Internet Archive}}</ref> |

|||

[[Bosley Crowther]] of ''[[The New York Times]]'' felt the film's opening "makes for a dynamic and illustrative sequence on the screen. But once the land rush is over in this almost two-and-one-half-hour-long film—and we have to tell you it is assembled and completed within the first half-hour—the remaining dramatization of Miss Ferber's bursting 'Cimarron' simmers down to a stereotyped and sentimental cinema saga of the taming of the frontier."<ref>{{cite news |last=Crowther |first=Bosley |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1961/02/17/archives/screen-new-cimarronremake-of-book-opens-at-the-music-hall.html |title=Screen: New 'Cimarron' |work=The New York Times |page=21 |date=February 17, 1961 |access-date=January 4, 2022}}</ref> A review in ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' magazine criticized the film's length, writing ''Cimarron'' "might more suitably have been called Cimarron-and-on-and-on-and-on. It lasts 2 hours and 27 minutes, and for at least half of that time most spectators will probably be Oklacomatose."<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,828789,00.html |title=Cinema: Oklacoma |magazine=Time |date=February 24, 1961 |access-date=January 4, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

The 1960 remake is considered a [[revisionist western]] for its sympathetic portrayal of indigenous Americans and view of their racist mistreatment as unjust,<ref>{{cite book|title=Hollywood's Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film|author= Peter Rollins}}</ref> which appeared at the time that the [[Civil rights movement]] was gaining momentum in the U.S.<ref name=":0">[[Cimarron (novel)|Cimarron (novel) – Wikipedia]]</ref>{{Circular reference|date=December 2019}} |

|||

In a letter published in ''The New York Times'', on March 5, 1961, Edna Ferber wrote: "I received from this second picture of my novel not one single penny in payment. I can't even do anything to stop the motion-picture company from using my name in advertising so slanted that it gives the effect of my having written the picture ... I shan't go into the anachronisms in dialogue; the selection of a foreign-born actress...to play the part of an American-born bride; the repetition; the bewildering lack of sequence....I did see ''Cimarron''...four weeks ago. This old gray head turned almost black during those two (or was it three?) hours."<ref>{{cite news |last=Ferber |first=Edna |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1961/03/05/archives/letter-to-the-editor-1-no-title.html |title=Readers Appraise the Current Crop of Pictures |work=The New York Times |page=X7 |date=March 5, 1961 |access-date=October 26, 2023 |url-access=subscription}}</ref> |

|||

In the 1931 film, Yancey is presented as an advocate for Native Americans from the beginning. The fact that he uses his skills as a lawyer to defend and assist them is one of the reasons Sabra's family despises and fears him, and he has a reputation in Oklahoma because of it. He does not stop being a lawyer, as he does in the 1960 film.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://catalog.afi.com/Film/899-CIMARRON?sid=b637a2db-dc08-4c9a-b935-03d8f259db29&sr=15.931137&cp=1&pos=1|title=AFI{{!}}Catalog|website=catalog.afi.com|access-date=2019-12-15}}</ref> (The character was based on [[Temple Lea Houston]].)<ref name=":0" /> In the 1960 film, Yancey's support of the Native Americans is not shown until the attack on the Red Feather family. |

|||

==Awards and nominations== |

|||

The 1960 adaptation deviates from the original story of the Ferber best-seller in many ways, including its focal point. James Tartara observes: "It makes sense that, rather than focusing on the more refined Sabra, who guided both Ferber's novel and the earlier filmic adaptation, [Director] Mann chose to focus more on Ford's gutsy adventurer. He also hoped to capture the drama of the changing Western landscape as it fills with settlers, a task that perfectly suited CinemaScope. " However, Mann quit the project in the middle of filming after a bitter clash with producer Edmund Grainger. Director Charles Walters, uncredited, shot all the rest.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web|url=http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/99252%7C0/Cimarron.html|title=Cimarron (1960)|website=Turner Classic Movies|access-date=2019-12-15}}</ref> Added to this was an ill-fated romance between the leads that left them barely speaking. Tartara says "The resulting picture is a striking example of the CinemaScope process while still being something of a creative mishmash. The critics were bored, audiences stayed away in droves, and MGM never earned a penny from it."<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | In 1961, the film was nominated for [[Academy Award for Best Production Design|Best Art Direction]] ([[George Davis (art director)|George W. Davis]], [[Addison Hehr]], [[Henry Grace]], [[Hugh Hunt]] and [[Otto Siegel]]) and [[Academy Award for Best Sound|Best Sound]] ([[Franklin Milton]]).<ref name="Oscars1961">{{Cite web|url=http://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1961 |title=The 33rd Academy Awards (1961) Nominees and Winners |access-date=2011-08-22|work=oscars.org}}</ref><ref name="NY Times">{{cite web |url=https://movies.nytimes.com/movie/87266/Cimarron/details |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090813130744/http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/87266/Cimarron/details |url-status=dead |archive-date=2009-08-13 |department=Movies & TV Dept. |work=[[The New York Times]] |date=2009 |title=Cimarron |access-date=2008-12-24}}</ref> |

||

Glenn Ford's performance earned a nomination for a [[Laurel Awards|Laurel Award]] for Top Action Performance, though he did not win.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001229/|title=Glenn Ford|website=IMDb|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref> |

|||

Glenn Ford's performance in the film earned him a nomination for a [[Laurel Awards|Laurel Award]] for Top Action Performance (which he did not win).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001229/|title=Glenn Ford|website=IMDb|access-date=2019-02-15}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 178: | Line 165: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

===Footnotes=== |

|||

{{Reflist|group=lower-alpha}} |

|||

===Citations=== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

===Bibliography=== |

|||

{{Refbegin|40em}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Bassinger |first=Jeanne |author-link=Jeanine Basinger |title=Anthony Mann |url=https://archive.org/details/anthonymann00basi |year=2007 |publisher=[[Wesleyan University Press]] |isbn=978-0-819-56845-8 |url-access=registration}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Baxter |first=Anne |title=Intermission: A True Story |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_399115773/ |year=1976 |publisher=[[G. P. Putnam's Sons]] |isbn=978-0-399-11577-6 |url-access=registration}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* {{IMDb title|0053715|Cimarron}} |

* {{IMDb title|0053715|Cimarron}} |

||

* {{AllMovie title|87266|Cimarron}} |

|||

* {{TCMDb title|id=14909}} |

* {{TCMDb title|id=14909}} |

||

* {{AFI film|id=53484|title=Cimarron}} |

* {{AFI film|id=53484|title=Cimarron}} |

||

| Line 192: | Line 188: | ||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cimarron}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cimarron}} |

||

[[Category:1960 films]] |

[[Category:1960 films]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1960s English-language films]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:1960 Western (genre) films]] |

[[Category:1960 Western (genre) films]] |

||

[[Category:American epic films]] |

[[Category:American Western (genre) epic films]] |

||

[[Category:Films scored by Franz Waxman]] |

[[Category:Films scored by Franz Waxman]] |

||

[[Category:Films based on Western (genre) novels]] |

[[Category:Films based on Western (genre) novels]] |

||

| Line 203: | Line 198: | ||

[[Category:Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films]] |

[[Category:Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films]] |

||

[[Category:Films based on works by Edna Ferber]] |

[[Category:Films based on works by Edna Ferber]] |

||

[[Category:American |

[[Category:1960s American films]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Latest revision as of 19:15, 21 December 2024

| Cimarron | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Anthony Mann[a] |

| Screenplay by | Arnold Schulman |

| Based on | Cimarron 1930 novel by Edna Ferber |

| Produced by | Edmund Grainger |

| Starring | Glenn Ford Maria Schell Anne Baxter Harry Morgan |

| Cinematography | Robert Surtees |

| Edited by | John D. Dunning |

| Music by | Franz Waxman |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 147 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5,421,000[2] |

| Box office | $4,825,000[2] |

Cimarron is a 1960 American epic Western film based on the 1930 Edna Ferber novel Cimarron. The film stars Glenn Ford and Maria Schell and was directed by Anthony Mann and Charles Walters, though Walters is not credited onscreen.[1] Ferber's novel was previously adapted as a film in 1931; that version won three Academy Awards.

Cimarron was the first of three epics (along with El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire) that Mann directed. Despite high production costs and an experienced cast of Western veterans, stage actors and future stars, the film was released with little fanfare.

Plot

[edit]Sabra Cravat joins her new husband, lawyer Yancey "Cimarron" Cravat, during the Oklahoma land rush of 1889. They encounter Yancey's old friend William "The Kid" Hardy and his buddies Wes Jennings and Hoss Barry. On the trail, Yancey helps Tom and Sarah Wyatt and their eight children, taking them aboard their wagons.

It seems to Sabra that her husband knows everyone in Oklahoma. A small crowd cheers Bob Yountis and his henchman Millis when they attack an Indian family. Yancey joins his friend Sam Pegler, editor of the Oklahoma Wigwam newspaper, in resisting Yountis.

Yountis warns Pegler against using the paper for his crusading as he had done in Texas. Sabra is angry that Yancey risked his life for an Indian but she helps the others, including peddler Sol Levy and printer Jesse Rickey, in righting the Indians' overturned wagon. Sam and his wife Mavis reveal more about Yancey's past as a cowboy, gambler, gunman and lawyer.

When 50,000 settlers race across the prairie to claim land, Tom falls and Sarah claims a dry, worthless patch. Pegler is trampled to death, and Dixie beats Yancey to the land that he wanted, so he asks Jesse to stay to help him run the paper.

In the new town of Osage, which consists of tents and half-built storefronts, Yountis and The Kid terrorize Levy in the street. Yancey tries but fails to persuade the Kid to change. One night, Yountis leads a lynch mob against the Indian family. Yancey arrives too late to stop it, but he kills Yountis and brings Arita and her baby Ruby home. Meanwhile, Sabra gives birth to a boy whom they name Cimarron, Cim for short.

Four years later, Osage is thriving. Tom has built an oil-drilling apparatus but he is a laughingstock. Wes, Hoss and The Kid, wanted outlaws, try to rob a train but are all killed soon after. When Yancey destroys the $1,000 reward check, Sabra is furious because he does not consider their son's security. Yancey leaves to be part of the Cherokee Strip, but Sabra refuses to join him. Years later, he returns and Sabra and Cim forgive him.

Tom finally strikes oil, but Yancey is disgusted to learn that Tom bought the rights to oil found on Indian land. However, Yancey's campaign to win the Indians justice is a huge success, and he is invited to become governor of the Oklahoma Territory. Sabra is disappointed to discover that Cim and Ruby have grown close.

In Washington, D.C., Yancey finds Tom with a group of influential men and learns that the price of his appointment is his integrity. When Yancy tells Sabra that he can't be governor, she sends him away forever.

Cim and Ruby marry without warning and set off for Oregon, though Sabra tells him that he is throwing his life away.

Ten years later, on the occasion of the Oklahoma Wigwam's 25th anniversary, the United States’ entry into World War I is announced. Later, Sabra hears that Yancey has been killed in the war.

Cast

[edit]- Glenn Ford as Yancey Cravat

- Maria Schell as Sabra Cravat

- Anne Baxter as Dixie Lee

- Arthur O'Connell as Tom Wyatt

- Russ Tamblyn as William Hardy / The Cherokee Kid

- Mercedes McCambridge as Sarah Wyatt

- Vic Morrow as Wes Jennings

- Robert Keith as Sam Pegler

- Charles McGraw as Bob Yountis

- Aline MacMahon as Mavis Pegler

- Harry Morgan as Jesse Rickey (Credited as Henry "Harry" Morgan)

- David Opatoshu as Sol Levy

- Edgar Buchanan as Judge Neal Hefner

- Lili Darvas as Felicia Venable

- Mary Wickes as Mrs. Neal Hefner

- Royal Dano as Ike Howes

- L. Q. Jones as Millis

- George Brenlin as Hoss Barry

- Vladimir Sokoloff as Jacob Krubeckoff

- Eugene Jackson as Isaiah

- Uncredited

- Andy Albin as Water Man

- Rayford Barnes as Cavalry Sergeant Who Breaks Up Fight

- Herman Belmonte as Dancer At Ball

- Mary Benoit as Mrs. Lancey

- Barry Bernard as Butler

- Jimmie Booth as Wagon Driver

- Danny Borzage as Townsman

- Chet Brandenburg as Townsman

- Janet Brandt as Madam Rhoda

- Paul Bryar as Mr. Self, Politician

- Robert Carson as Senator Rollins

- John L. Cason as Suggs

- William Challee as The Barber

- Mickie Chouteau as Ruby Red Feather

- Fred Coby as Oil Worker

- Gene Coogan as Butler / Townsman

- Jack Daly as Wyatt's Man

- John Damler as Foreman

- Richard Davies as Mr. Hodges

- George DeNormand as Townsman At Celebration

- James Dime as Townsman

- Phyllis Douglas as Sadie

- Ted Eccles as Cimarron Cravat – Age 2

- LaRue Farlow as Dancer

- Franklyn Farnum as Townsman At Schoolhouse

- George Ford as Townsman At Celebration

- Coleman Francis as Mr. Geer

- Ben Gary as Reporter

- James Halferty as Cimarron Cravat – Age 10

- Sam Harris as Ball Guest

- Lars Hensen as Dancer At Ball

- Clegg Hoyt as "Great" Gotch

- Irene James as Townswoman

- Colin Kenny as Townsman At Schoolhouse

- Paul Kruger as Party Guest

- Jimmy Lewis as Hefner Boy

- Dawn Little Sky as Arita Red Feather

- Eddie Little Sky as Ben Red Feather

- Buzz Martin as Cimarron Cravat as Young Man

- Kermit Maynard as Setter

- Mathew McCue as Townsman

- J. Edward McKinley as Beck

- Walter Merrill as Reporter

- Jack Perry as Townsman

- John Pickard as Ned, Cavalry Captain

- Ralph Reed as Bellboy

- William Remick as Reporter

- Gene Roth as Connors

- Jack Scroggy as Walter

- Charles Seel as Charles

- Bernard Sell as Townsman At Celebration

- Jack Stoney as Man At Lynching

- Harry Tenbrook as Sooner At Camp Fight

- Arthur Tovey as Dancer At Ball

- Ivan Triesault as Lewis Venable, Sabra's Father

- Charles Watts as Lou Brothers, Politician

- Helen Westcott as Miss Kuye, Schoolteacher

- Robert Williams as Oil Worker

- Jeane Wood as Clubwoman

- Wilson Wood as Reporter

- Jorie Wyler as Theresa Jump

Production

[edit]In February 1941, MGM bought the remake rights to Cimarron from RKO for $100,000.[3] In 1947, MGM announced an operetta version starring Kathryn Grayson and produced by Arthur Freed,[4] but this did not happen. In February 1958, MGM announced its plans to produce Cimarron as the studio's second film using the MGM Camera 65 process following Raintree Country (1957).[5][6] One month later, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson were considered to star in the film.[7] Ultimately, Glenn Ford, who previously starred in the Westerns such as 3:10 to Yuma (1957) and The Sheepman (1958), was attached to star.[8] In October 1959, Arnold Schulman was signed to write the screenplay.[9] For his script, Schulman introduced several characters, including those of journalist Sam Pegler (Robert Keith) and Wes Jennings (Vic Morrow), while removing the Cravats' daughter, Donna and a boy named Isaiah.[1] King Vidor declined an invitation to direct.[10]

Anthony Mann was eventually named as director. He had pitched to his vision to MGM executives, explaining: "I wanted to show a huge plain out in the West with nothing on it, and how a group of men and women gathered at a line, and tore out across this plain and set up their stakes as claim for the land. And how a town, a city and finally a metropolis grew, all on this one piece of land."[11] Principal photography was shot in Arizona, most particularly the depiction of the Oklahoma Land Rush,[12] which featured over 1,000 extras, 700 horses and 500 wagons and buggies.[13]

As production continued, the on-location shoot experienced dust storms, in which producer Edmund Grainger decided to relocate the production on the studio backlot despite Mann's insistence to film entirely on location.[14] Mann explained: "We had a couple of storms—which I shot in anyway—but they thought we'd have floods and so on, so they dragged us in and everything had to be duplicated on the set. The story had to be changed, because we couldn't do the things we wanted to. So I don't consider it a film. I just consider it a disaster."[11] Mann left the production, and director Charles Walters finished the film but received no screen credit.[1] Mann was also critical of the film's final cut, explaining that Ford was meant to die on screen. Years later, he explained: "There was a huge oil sequence and oil wells were blowing up and he was saving people and being very heroic. Why they ever changed it I'll never know – this was Mr. Sol Siegel, he did it behind my back, I didn't ever see it. If I'd screamed they wouldn't have bothered anyway; so I just let them destroy it at will."[11]

Also, during filming, Anne Baxter, who played Dixie Lee, revealed in her autobiography Intermission that Ford and Maria Schell developed an offscreen romance: "During shooting, they'd scrambled together like eggs. I understood she'd even begun divorce proceedings in Germany. It was obviously premature of her." However, by the end of filming, "... he scarcely glanced or spoke in her direction, and she looked as if she were in shock."[15]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]According to MGM records, Cimarron earned $2,325,000 in the U.S. and Canada and $2,500,000 overseas, resulting in an overall loss of $3,618,000.[2]

Critical reaction

[edit]Harrison's Reports wrote: "The background music is undistinguished. There's enough marquee strength, action, romance, and the 'land rush' scene at the beginning is worth the price of a soft ticket. Color photography is outstanding."[16] Thomas M. Pryor, reviewing for Variety, praised Schell and Ford's performances, and wrote "Although Cimarron is not without flaws—thoughtful examination reveals a pretentiousness of social significance more than valid exposition—the script plays well."[17]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times felt the film's opening "makes for a dynamic and illustrative sequence on the screen. But once the land rush is over in this almost two-and-one-half-hour-long film—and we have to tell you it is assembled and completed within the first half-hour—the remaining dramatization of Miss Ferber's bursting 'Cimarron' simmers down to a stereotyped and sentimental cinema saga of the taming of the frontier."[18] A review in Time magazine criticized the film's length, writing Cimarron "might more suitably have been called Cimarron-and-on-and-on-and-on. It lasts 2 hours and 27 minutes, and for at least half of that time most spectators will probably be Oklacomatose."[19]

In a letter published in The New York Times, on March 5, 1961, Edna Ferber wrote: "I received from this second picture of my novel not one single penny in payment. I can't even do anything to stop the motion-picture company from using my name in advertising so slanted that it gives the effect of my having written the picture ... I shan't go into the anachronisms in dialogue; the selection of a foreign-born actress...to play the part of an American-born bride; the repetition; the bewildering lack of sequence....I did see Cimarron...four weeks ago. This old gray head turned almost black during those two (or was it three?) hours."[20]

Awards and nominations

[edit]In 1961, the film was nominated for Best Art Direction (George W. Davis, Addison Hehr, Henry Grace, Hugh Hunt and Otto Siegel) and Best Sound (Franklin Milton).[21][22]

Glenn Ford's performance earned a nomination for a Laurel Award for Top Action Performance, though he did not win.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ During the middle of filming, Mann left the project and was replaced by Charles Walters who was uncredited.[1]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Tatara, Paul. "Cimarron (1960)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ a b c Mannix, Eddie (1962). The Eddie Mannix Ledger. Margaret Herrick Library. OCLC 801258228.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ "Metro Buys 'Cimarron' Rights From RKO for $100,000". The New York Times. February 22, 1941. p. 11.

- ^ Brady, Thomas F. (November 24, 1947). "'Cimarron' Remake Listed by Metro". The New York Times. p. 30.

- ^ "Metro Remakes 'Cimarron'". Variety. February 26, 1958. p. 20. Retrieved September 28, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pryor, Thomas M. (February 20, 1958). "U.S. vs. Al Capone To Be Film Theme". The New York Times. p. 29.

- ^ "41 Westerns On Hoof in 1958". Variety. March 5, 1958. p. 4. Retrieved January 4, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Scheuer, Philip K. (February 17, 1959). "Glenn Ford Value Seen as 'Built' Star: Ava Gardner His Likely Lead; Producer Cites Other Examples". Los Angeles Times. p. C7.

- ^ "Schulman Forms Production Unit". The New York Times. October 8, 1959. p. 49.

- ^ "Entertainment Films Stage Music: Viertel Film Will Not Star Deborah". Los Angeles Times. September 11, 1959. p. B6.

- ^ a b c Wicking, Christopher; Pattinson, Barrie (July–October 1969). "Interviews with Anthony Mann". Screen. Vol. 10. pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rothwell, John H. (January 10, 1960). "Shot on the Old 'Cimarron' Trail". The New York Times. p. X7.

- ^ "Cimarron (1960)—AFI Catalog of Feature Films". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved June 16, 2024.

- ^ Bassinger 2007, p. 146.

- ^ Baxter 1976, p. 196.

- ^ "'Cimarron' with Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, Anne Baxter". Harrison's Reports. December 10, 1960. p. 198. Retrieved January 4, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Cimarron". Variety. December 7, 1960. p. 6. Retrieved January 4, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (February 17, 1961). "Screen: New 'Cimarron'". The New York Times. p. 21. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ "Cinema: Oklacoma". Time. February 24, 1961. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- ^ Ferber, Edna (March 5, 1961). "Readers Appraise the Current Crop of Pictures". The New York Times. p. X7. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "The 33rd Academy Awards (1961) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved August 22, 2011.

- ^ "Cimarron". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2009. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved December 24, 2008.

- ^ "Glenn Ford". IMDb. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bassinger, Jeanne (2007). Anthony Mann. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-819-56845-8.

- Baxter, Anne (1976). Intermission: A True Story. G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-399-11577-6.

External links

[edit]- Cimarron at IMDb

- Cimarron at the TCM Movie Database

- Cimarron at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- 1960 films

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960 Western (genre) films

- American Western (genre) epic films

- Films scored by Franz Waxman

- Films based on Western (genre) novels

- Films directed by Anthony Mann

- Films based on American novels

- Films set in Oklahoma

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films based on works by Edna Ferber

- 1960s American films

- English-language Western (genre) films