Tiber Creek: Difference between revisions

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Reformat 1 archive link. Wayback Medic 2.5 |

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Rescued 1 archive link; reformat 1 link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| image = White Lot during the war, Washington D.C. Shows Tiber River, now "B" St. - NARA - 529253.jpg |

| image = White Lot during the war, Washington D.C. Shows Tiber River, now "B" St. - NARA - 529253.jpg |

||

| image_size = 300px |

| image_size = 300px |

||

| image_caption = <sup>[[National Archives at College Park]]</sup><br>''White Lot during the war, Washington D.C. Shows Tiber River, now [[Constitution Avenue|"B" St.]]'', {{circa|1860–1865}} |

| image_caption = <sup>[[National Archives at College Park]]</sup><br>''White Lot during the war, Washington D.C. Shows Tiber River, now [[Constitution Avenue|"B" St.]]'', {{circa|1860–1865}}. |

||

| image_alt = |

| image_alt = |

||

| map = |

| map = |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

| mouth = |

| mouth = |

||

| mouth_location = [[National Mall]] |

| mouth_location = [[National Mall]] |

||

|mouth_coordinates={{coord|38.8906675|-77.0391435|format=dms|type:landmark_region:US-DC|display=inline,title}}<ref name=gnis>{{cite gnis|id=531312|name=Tiber Creek (historical)|entrydate=April 1, 1993| |

|mouth_coordinates={{coord|38.8906675|-77.0391435|format=dms|type:landmark_region:US-DC|display=inline,title}}<ref name=gnis>{{cite gnis|id=531312|name=Tiber Creek (historical)|entrydate=April 1, 1993|access-date=December 18, 2019}}</ref> |

||

| mouth_elevation = |

| mouth_elevation = |

||

| progression = |

| progression = |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{refimprove|date=October 2020}} |

|||

'''Tiber Creek''' or '''Tyber Creek''', originally named '''Goose Creek''', is a [[tributary]] of the [[Potomac River]] in [[Washington, D.C.]] |

'''Tiber Creek''' or '''Tyber Creek''', originally named '''Goose Creek''', is a [[tributary]] of the [[Potomac River]] in [[Washington, D.C.]] It was a free-flowing creek until 1815, when it was channeled to become part of the [[Washington City Canal]]. Presently, it flows under the city in tunnels, including under [[Constitution Avenue]] NW. |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:Tiber Creek north-east of the Capitol. Washington, D.C. LCCN2004662005.jpg|thumb|Landscape showing a train crossing Tiber Creek, northeast of the Capitol (not pictured) in Washington, DC in 1839]] |

|||

Originally called ''Goose Creek'', it was renamed by settler Francis Pope. Pope owned a {{convert|400|acre|km2|sing=on}} farmstead along the banks of the creek which, in a play on his surname, he named "Rome" after the [[Rome|Italian city]], and he renamed the creek in honor of the river which flows through that city.<ref name="Mr Jenkins">''[http://capitolhillhistory.org/library/04/Jenkins%20Hill.html The Mysterious Mr. Jenkins of Jenkins Hill: The Early History of the Capitol Site]'' - John Michael Vlach (Spring 2004)</ref> |

|||

Originally named Goose Creek, it was renamed during the late 1600s by settler Francis Pope, who owned a {{convert|400|acre|km2|sing=on}} farmstead along the banks of the creek. Dubbing his land "[[Rome]]", Pope renamed the creek after the Italian city's [[Tiber|river]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2014-02-11 |title=Washington Was Originally Named Rome, Maryland |url=https://ghostsofdc.org/2014/02/11/washington-originally-called-rome/ |access-date=2021-12-23 |website=Ghosts of DC}}</ref> |

|||

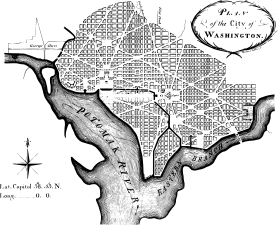

Using the original Tiber Creek for commercial purposes was part of [[Pierre Charles L’Enfant|Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's]] 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States . . .".<ref>[https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri001.html "Original Plan of Washington, D.C."] U.S. Library of Congress. Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref> The idea was that the creek could be widened and channeled into a canal to the Potomac. By 1815 the western portion of the creek became part of the [[Washington City Canal]], running along what is now [[Constitution Avenue]].<ref>Cornelius W. Heine (1953). [https://www.jstor.org/pss/40067664 "The Washington City Canal."] ''Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C.'' '''53-56''' (1953-56) 1-27. Now called [http://www.historydc.org/media/publications/ Historical Society of Washington, DC.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091207014533/http://www.historydc.org/media/publications/ |date=2009-12-07 }}</ref> By the 1840s, |

Using the original Tiber Creek for commercial purposes was part of [[Pierre Charles L’Enfant|Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's]] 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States . . .".<ref>[https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/tri001.html "Original Plan of Washington, D.C."] U.S. Library of Congress. Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref> The idea was that the creek could be widened and channeled into a canal to the Potomac. By 1815 the western portion of the creek became part of the [[Washington City Canal]], running along what is now [[Constitution Avenue]].<ref>Cornelius W. Heine (1953). [https://www.jstor.org/pss/40067664 "The Washington City Canal."] ''Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C.'' '''53-56''' (1953-56) 1-27. Now called [http://www.historydc.org/media/publications/ Historical Society of Washington, DC.] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091207014533/http://www.historydc.org/media/publications/ |date=2009-12-07 }}</ref> By the 1840s, when Washington had no separate storm drain and sewer system, the Washington City Canal had become a notorious open sewer. When [[Alexander "Boss" Shepherd]] joined the D.C. Board of Public Works in 1871, he and the Board engaged in a massive, albeit uneven, series of infrastructure improvements, including grading and paving streets, planting trees, installing sewers and laying out parks. One of these projects enclosed Tiber Creek and the Washington City Canal. A German immigrant engineer named [[Adolf Cluss]], also on the Board, is credited with constructing a tunnel from Capitol Hill to the Potomac "wide enough for a bus to drive through to put Tiber Creek underground."<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20090808115930/http://geocities.com/garygrassl@verizon.net/index.html German-American Heritage Society of Washington, D.C.] Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref><ref>{{usurped|1=[https://archive.today/20120910025134/http://www.sewerhistory.org/articles/compon/1894_aen03/index.htm "The Tiber Creek Sewer Flush Gates, Washington, D.C."]}}, ''Engineering News and American Railway Journal'', February 8, 1894.</ref> |

||

Many of the buildings on the north side of Constitution Avenue apparently are built on top of the creek, including the [[Internal Revenue Service Building]], part of which is built on wooden piers sunk into the wet ground along the creek course. |

Many of the buildings on the north side of Constitution Avenue apparently are built on top of the creek, including the [[Internal Revenue Service Building]] (IRS), part of which is built on wooden piers sunk into the wet ground along the creek course. The low-lying topography there contributed to the flooding of the [[National Archives and Records Administration#National Archives Building|National Archives Building]] (Archives I in Washington, D.C.), IRS headquarters, and [[William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building]] that forced their temporary closure beginning in late June 2006. Until the mid-1990s, land near the intersection of [[14th Street Northwest and Southwest (Washington, D.C.)|14th Street]] and Constitution Avenue was a parking lot because the underground water was too difficult to deal with. During construction of the [[Ronald Reagan Building]] (1990–98), the engineers diverted the water. The dewatering then reduced the water level underneath the IRS building which caused the wooden piers to lose stability and part of the IRS building foundation to sink.{{Citation needed|date=May 2022}} |

||

A [[public house|pub]] near Tiber Creek's historic course north of Capitol Hill was named after it. The Bistro Bis restaurant now occupies the Tiber Creek Pub's former location.<ref>Goldreich, Samuel (1998). [https://www.questia.com/read/1G1-56758917 "Bistro Bis succeeds Capitol Hill pub as welcoming lunch option."] ''Washington Times.'' 1998-10-12.</ref> A [[Lockkeeper's House, C & O Canal Extension|lock keeper's house]] from the Washington branch of the [[Chesapeake and Ohio Canal]] remains at the southwest corner of Constitution Avenue and 17th Street, NW, near the former mouth of Tiber Creek, and the western end of the Washington City Canal.<ref>dcMemorials.com. [http://dcmemorials.com/index_indiv0001032.htm Plaque beside the Lockkeeper's House marking the former location in Washington, D.C.] Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref><ref>HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. [http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=209 "Lock Keeper’s House Marker."] Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref><ref>Coordinates of lock keeper's house: {{coord|38.8919305|-77.0397498|scale:1000|name=Lockkeeper's house from Washington branch of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal}}</ref> |

A [[public house|pub]] near Tiber Creek's historic course north of Capitol Hill was named after it. The Bistro Bis restaurant now occupies the Tiber Creek Pub's former location.<ref>Goldreich, Samuel (1998). [https://www.questia.com/read/1G1-56758917 "Bistro Bis succeeds Capitol Hill pub as welcoming lunch option."] ''Washington Times.'' 1998-10-12.</ref> A [[Lockkeeper's House, C & O Canal Extension|lock keeper's house]] from the Washington branch of the [[Chesapeake and Ohio Canal]] remains at the southwest corner of Constitution Avenue and 17th Street, NW, near the former mouth of Tiber Creek, and the western end of the Washington City Canal.<ref>dcMemorials.com. [http://dcmemorials.com/index_indiv0001032.htm Plaque beside the Lockkeeper's House marking the former location in Washington, D.C.] Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref><ref>HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. [http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=209 "Lock Keeper’s House Marker."] Accessed 2009-09-16.</ref><ref>Coordinates of lock keeper's house: {{coord|38.8919305|-77.0397498|scale:1000|name=Lockkeeper's house from Washington branch of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal}}</ref> |

||

| Line 80: | Line 82: | ||

According to General James Wilkinson's memoirs, "I may be excused for mention another incident, which deeply interested [...] my family. My father, to preserve his health and property, purchased 500 acres of land lying on the Tyber and Potomack, which probably comprises the President's house; but at the time, about 1762, the present seat of government was considered so remote from the early settlements of the province, that my mother objected to the removal on accounts of the distance, and my father transferred the property to Thomas Johns, esq. a friend and contemporary, of his neighborhood, to whose family it proved an auspicious contract; but in this case, the benefactor did not long enjoy the prosperity he had promoted."<ref>Memoirs of My Own Times, General James Wilkinson. Pg 9.</ref> |

According to General James Wilkinson's memoirs, "I may be excused for mention another incident, which deeply interested [...] my family. My father, to preserve his health and property, purchased 500 acres of land lying on the Tyber and Potomack, which probably comprises the President's house; but at the time, about 1762, the present seat of government was considered so remote from the early settlements of the province, that my mother objected to the removal on accounts of the distance, and my father transferred the property to Thomas Johns, esq. a friend and contemporary, of his neighborhood, to whose family it proved an auspicious contract; but in this case, the benefactor did not long enjoy the prosperity he had promoted."<ref>Memoirs of My Own Times, General James Wilkinson. Pg 9.</ref> |

||

Presently, the stream flowing under the city is often referred to as ''Tiber Creek'' though its common past with the Canal is acknowledged.<ref>[https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/what-youd-see-in-washingtons-tiber-creek-sewer--if-you-dared/2013/08/28/cb3a2876-0fe4-11e3-85b6-d27422650fd5_story.html What you’d see in Washington’s Tiber Creek sewer — if you dared to go] - The Washington Post - John Kelly - August 28, 2013</ref> |

|||

{{See also|Washington City Canal}} |

{{See also|Washington City Canal}} |

||

| Line 86: | Line 88: | ||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="150"> |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="150"> |

||

Image:DC-old-and-new.jpg|Tiber/Goose Creek around 1800, and the modern shorelines of the Potomac River |

Image:DC-old-and-new.jpg|Tiber/Goose Creek around 1800, and the modern shorelines of the Potomac River |

||

Image:L'Enfant plan. |

Image:L'Enfant plan.svg|[[Andrew Ellicott|Andrew Ellicott's]] revision of L'Enfant's Plan, showing Washington City Canal |

||

File:(Survey_of_the_original_landholdings_in_Washington_D.C._in_the_area_bounded_by_The_Mall,_North_Capitol_St.,_Tiber_Creek,_N_St._N.W.,_and_Seventh_St._N.W.)_LOC_87694238.jpg|Survey map showing Goose Creek running along North Capitol Street in 1855 |

File:(Survey_of_the_original_landholdings_in_Washington_D.C._in_the_area_bounded_by_The_Mall,_North_Capitol_St.,_Tiber_Creek,_N_St._N.W.,_and_Seventh_St._N.W.)_LOC_87694238.jpg|Survey map showing Goose Creek running along North Capitol Street in 1855 |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

==Location and Course== |

==Location and Course== |

||

It |

It lay southeast of then [[Georgetown, Washington, D.C.|Georgetown]], [[Maryland]], amid lands that were selected for the City of Washington, the new capital of the [[United States]].<ref name="Mr Jenkins">{{Cite web|date=2018-10-10|title=The Mysterious Mr. Jenkins of Jenkins Hill|url=http://www.capitolhillhistory.org/library/04/Jenkins%20Hill.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181010024821/http://www.capitolhillhistory.org/library/04/Jenkins%20Hill.html|archive-date=October 10, 2018|access-date=2020-10-22}}</ref> Presently this land is the [[National Mall]]. |

||

Several small streams flowed from the north and south meeting at the base of [[United States Capitol|Capitol Hill]] then heading west to flow into the [[Potomac River]] near [[Jefferson Pier]]. The overall course of the creek was kept when the Canal was built |

Several small streams flowed from the north and south meeting at the base of [[United States Capitol|Capitol Hill]] then heading west to flow into the [[Potomac River]] near [[Jefferson Pier]]. The overall course of the creek was kept when the Canal was built during 1815. |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 99: | Line 101: | ||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

*{{cite web|last1=Ramos|first1=David|title=DC streams in 1859, plotted on a modern map| |

*{{cite web|last1=Ramos|first1=David|title=DC streams in 1859, plotted on a modern map|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141025102642/http://imaginaryterrain.com/blog/2013/07/streams/|archive-date=October 25, 2014|url=http://imaginaryterrain.com/blog/2013/07/streams/|work=Imaginary Terrain|date=July 7, 2013}} |

||

*{{cite web|last1=Williams|first1=Garnett P.|title=Washington D.C.'s Vanishing Springs and Waterways: Geological Survey Circular 752|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1977/0752/report.pdf|location=Washington, D.C.|publisher=[[United States Department of the Interior]]|date=1977|access-date=March 15, 2015}} |

*{{cite web|last1=Williams|first1=Garnett P.|title=Washington D.C.'s Vanishing Springs and Waterways: Geological Survey Circular 752|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1977/0752/report.pdf|location=Washington, D.C.|publisher=[[United States Department of the Interior]]|date=1977|access-date=March 15, 2015}} |

||

Latest revision as of 03:04, 22 December 2024

Tiber Creek

| |

|---|---|

National Archives at College Park White Lot during the war, Washington D.C. Shows Tiber River, now "B" St., c. 1860–1865. | |

| |

| Etymology | Tiber River in Rome, Italy |

| Location | |

| Country | U.S. |

| District | District of Columbia |

| City | Washington, D.C. |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Shaw neighborhood |

| • coordinates | 38°54′56″N 77°01′13″W / 38.9155556°N 77.0202778°W[1] |

| Mouth | |

• location | National Mall |

• coordinates | 38°53′26″N 77°02′21″W / 38.8906675°N 77.0391435°W[1] |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Potomac River |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Tiber Creek or Tyber Creek, originally named Goose Creek, is a tributary of the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. It was a free-flowing creek until 1815, when it was channeled to become part of the Washington City Canal. Presently, it flows under the city in tunnels, including under Constitution Avenue NW.

History

[edit]

Originally named Goose Creek, it was renamed during the late 1600s by settler Francis Pope, who owned a 400-acre (1.6 km2) farmstead along the banks of the creek. Dubbing his land "Rome", Pope renamed the creek after the Italian city's river.[2]

Using the original Tiber Creek for commercial purposes was part of Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's 1791 "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States . . .".[3] The idea was that the creek could be widened and channeled into a canal to the Potomac. By 1815 the western portion of the creek became part of the Washington City Canal, running along what is now Constitution Avenue.[4] By the 1840s, when Washington had no separate storm drain and sewer system, the Washington City Canal had become a notorious open sewer. When Alexander "Boss" Shepherd joined the D.C. Board of Public Works in 1871, he and the Board engaged in a massive, albeit uneven, series of infrastructure improvements, including grading and paving streets, planting trees, installing sewers and laying out parks. One of these projects enclosed Tiber Creek and the Washington City Canal. A German immigrant engineer named Adolf Cluss, also on the Board, is credited with constructing a tunnel from Capitol Hill to the Potomac "wide enough for a bus to drive through to put Tiber Creek underground."[5][6]

Many of the buildings on the north side of Constitution Avenue apparently are built on top of the creek, including the Internal Revenue Service Building (IRS), part of which is built on wooden piers sunk into the wet ground along the creek course. The low-lying topography there contributed to the flooding of the National Archives Building (Archives I in Washington, D.C.), IRS headquarters, and William Jefferson Clinton Federal Building that forced their temporary closure beginning in late June 2006. Until the mid-1990s, land near the intersection of 14th Street and Constitution Avenue was a parking lot because the underground water was too difficult to deal with. During construction of the Ronald Reagan Building (1990–98), the engineers diverted the water. The dewatering then reduced the water level underneath the IRS building which caused the wooden piers to lose stability and part of the IRS building foundation to sink.[citation needed]

A pub near Tiber Creek's historic course north of Capitol Hill was named after it. The Bistro Bis restaurant now occupies the Tiber Creek Pub's former location.[7] A lock keeper's house from the Washington branch of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal remains at the southwest corner of Constitution Avenue and 17th Street, NW, near the former mouth of Tiber Creek, and the western end of the Washington City Canal.[8][9][10]

According to General James Wilkinson's memoirs, "I may be excused for mention another incident, which deeply interested [...] my family. My father, to preserve his health and property, purchased 500 acres of land lying on the Tyber and Potomack, which probably comprises the President's house; but at the time, about 1762, the present seat of government was considered so remote from the early settlements of the province, that my mother objected to the removal on accounts of the distance, and my father transferred the property to Thomas Johns, esq. a friend and contemporary, of his neighborhood, to whose family it proved an auspicious contract; but in this case, the benefactor did not long enjoy the prosperity he had promoted."[11]

Presently, the stream flowing under the city is often referred to as Tiber Creek though its common past with the Canal is acknowledged.[12]

-

Tiber/Goose Creek around 1800, and the modern shorelines of the Potomac River

-

Andrew Ellicott's revision of L'Enfant's Plan, showing Washington City Canal

-

Survey map showing Goose Creek running along North Capitol Street in 1855

Location and Course

[edit]It lay southeast of then Georgetown, Maryland, amid lands that were selected for the City of Washington, the new capital of the United States.[13] Presently this land is the National Mall.

Several small streams flowed from the north and south meeting at the base of Capitol Hill then heading west to flow into the Potomac River near Jefferson Pier. The overall course of the creek was kept when the Canal was built during 1815.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Tiber Creek (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. April 1, 1993. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "Washington Was Originally Named Rome, Maryland". Ghosts of DC. February 11, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2021.

- ^ "Original Plan of Washington, D.C." U.S. Library of Congress. Accessed 2009-09-16.

- ^ Cornelius W. Heine (1953). "The Washington City Canal." Records of the Columbia Historical Society of Washington, D.C. 53-56 (1953-56) 1-27. Now called Historical Society of Washington, DC. Archived 2009-12-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German-American Heritage Society of Washington, D.C. Accessed 2009-09-16.

- ^ "The Tiber Creek Sewer Flush Gates, Washington, D.C."[usurped], Engineering News and American Railway Journal, February 8, 1894.

- ^ Goldreich, Samuel (1998). "Bistro Bis succeeds Capitol Hill pub as welcoming lunch option." Washington Times. 1998-10-12.

- ^ dcMemorials.com. Plaque beside the Lockkeeper's House marking the former location in Washington, D.C. Accessed 2009-09-16.

- ^ HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. "Lock Keeper’s House Marker." Accessed 2009-09-16.

- ^ Coordinates of lock keeper's house: 38°53′31″N 77°02′23″W / 38.8919305°N 77.0397498°W

- ^ Memoirs of My Own Times, General James Wilkinson. Pg 9.

- ^ What you’d see in Washington’s Tiber Creek sewer — if you dared to go - The Washington Post - John Kelly - August 28, 2013

- ^ "The Mysterious Mr. Jenkins of Jenkins Hill". October 10, 2018. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Ramos, David (July 7, 2013). "DC streams in 1859, plotted on a modern map". Imaginary Terrain. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014.

- Williams, Garnett P. (1977). "Washington D.C.'s Vanishing Springs and Waterways: Geological Survey Circular 752" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to Tiber Creek at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tiber Creek at Wikimedia Commons- Painting of John Quincy Adams on Tiber Creek, by Peter Waddell, 2009, at the White House Historical Association

- "Tiber Creek" at Histories of the National Mall