War of 1812: Difference between revisions

→Bibliography: cite book |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|1812–1815 conflict in North America}} |

|||

{{About|the Anglo-American War of 1812 to 1815|the Franco-Russian conflict|French invasion of Russia|other uses of this term|War of 1812 (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{about|the conflict in North America from 1812 to 1815|the Franco–Russian conflict|French invasion of Russia|other uses of this term|War of 1812 (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{pp-pc1|expiry=June 16, 2017}} |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use Canadian English|date=March 2016}} |

|||

{{use dmy dates|date=June 2018}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2013}} |

|||

{{Infobox military conflict |

{{Infobox military conflict |

||

|conflict=War of 1812 |

| conflict = War of 1812 |

||

| partof = the [[Sixty Years' War]] |

|||

|partof= |

|||

|image= |

| image = War of 1812 Montage.jpg |

||

| image_size = 300 |

|||

|caption=Clockwise from top: damage to the [[United States Capitol|U.S. Capitol]] after the [[Burning of Washington]]; the mortally wounded {{nowrap|[[Isaac Brock]]}} spurs on the [[2nd Regiment of York Militia|York Volunteers]] at the [[battle of Queenston Heights]]; [[USS Constitution vs HMS Guerriere|USS ''Constitution'' vs HMS ''Guerriere'']]; [[Battle of the Thames|The death of]] [[Tecumseh]] in 1813 ends the Indian armed struggle in the American Midwest; {{nowrap|[[Andrew Jackson]]}} defeats the [[Battle of New Orleans|British assault on New Orleans]]. |

|||

| caption = Clockwise from top: |

|||

|date=June 18, 1812 – February 18, 1815<br />({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=06|day1=18|year1=1812|month2=02|day2=18|year2=1815}}) |

|||

{{flatlist| |

|||

|place= Eastern and Central North America, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans |

|||

* Damage to the [[United States Capitol]] after the [[burning of Washington]] |

|||

|casus= |

|||

* Mortally wounded [[Isaac Brock]] spurs on the [[2nd Regiment of York Militia|York Volunteers]] at the [[battle of Queenston Heights]] |

|||

|territory= |

|||

* [[USS Constitution vs HMS Guerriere|USS ''Constitution'' vs HMS ''Guerriere'']] |

|||

|result= [[Treaty of Ghent]] |

|||

* [[Battle of the Thames|The death]] of [[Tecumseh]] in 1813 |

|||

* Military stalemate |

|||

* [[Andrew Jackson]] defeats the [[Battle of New Orleans|British assault]] on [[New Orleans]] in 1815 |

|||

* American invasions of Canada repulsed |

|||

}} |

|||

* British invasions of USA repulsed |

|||

| date = 18 June 1812{{snd}}17 February 1815 |

|||

* ''[[Status quo ante bellum]]'' with no boundary changes |

|||

| place = {{ubl|class=nowrap|{{hlist|[[North America]]|[[Atlantic Ocean]]|[[Pacific Ocean]]}}}} |

|||

* Defeat of [[Tecumseh's Confederacy]] |

|||

| result = <!-- The refs are already cited in the main body. -->Inconclusive{{efn|see [[Results of the War of 1812]]}} |

|||

|combatant1= |

|||

| territory = * Anglo–American [[status quo ante bellum]] |

|||

{{flag|United States|1795}}<br> |

|||

* Spanish control over [[West Florida]] weakened and Mobile territory claimed |

|||

[[Native Americans in the United States|Native Americans]] |

|||

* [[Tecumseh's confederacy]] dissolved |

|||

[[Choctaw]], [[Cherokee]], [[Creek (people)|Creeks]] |

|||

| combatant1 = {{plainlist| |

|||

* {{flag|United States|1795}} |

|||

* [[Choctaw]] |

|||

* [[Cherokee]] |

|||

* [[Lower Creek]] |

|||

* [[Tuscarora people|Tuscarora]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| combatant2 = {{indented plainlist| |

|||

* {{flagcountry|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} |

|||

* [[Tecumseh's confederacy]] |

|||

* [[Red Sticks]] |

|||

* [[Menominee]] |

|||

* [[Six Nations of the Grand River]] |

|||

* {{flagicon|Spain|1785}} [[Spanish Florida]] (1814) |

|||

}} |

|||

| commander1 = {{ubl |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[James Madison]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[John Rodgers (1772–1838)|John Rodgers]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Stephen Decatur]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Andrew Jackson]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Henry Harrison]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Hull]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Winfield Scott]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| commander2 = {{ubl |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool|Earl of Liverpool]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[Philip Broke]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[George Prévost]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[Isaac Brock]]{{KIA}} |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[Robert Ross (British army officer)|Robert Ross]]{{KIA}} |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} [[Edward Pakenham]]{{KIA}} |

|||

| [[Tecumseh]]{{KIA}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| strength1 = {{ubli |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} 7,000 troops {{nwr|(at war's start)}} |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} 35,800 troops {{nwr|(at war's end)}} |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} 3,049 [[United States Rangers in the War of 1812|Rangers]] |

|||

| 458,463 [[Militia (United States)|militia]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} 12 [[Sailing frigate|Frigates]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United States|1795}} 14 other vessels |

|||

| 515 [[privateer]] ships{{sfn|Clodfelter|2017|p=245}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| strength2 = {{ubli |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|army}} 5,200 troops {{nwr|(at war's start)}} |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|army}} 48,160 troops {{nwr|(at war's end)}} |

|||

| 4,000 [[Canadian Militia]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|navy}} 11 [[ships of the line]] |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|navy}} 34 [[Sailing frigate|frigate]]s |

|||

| {{flagicon|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|navy}} 52 other vessels |

|||

| 9 [[Provincial Marine]] ships {{nwr|(at war's start)}} |

|||

| 10,000–15,000 Native American allies {{sfnm|Allen|1996|1p=121|Clodfelter|2017|2p=245}} |

|||

| 500 Spanish garrison troops (Pensacola){{sfn|Tucker et al.|2012|p=570}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| casualties1 = {{plainlist| |

|||

* 2,200 killed in action{{sfn|Clodfelter|2017|p=244}} |

|||

* 5,200 died of disease{{Sfn|Stagg|2012|p=156}} |

|||

* Up to 15,000 deaths from all causes{{Sfnm|Hickey|2006|1p=297|Stagg|2012|2p=156}} |

|||

* 4,505 wounded{{sfn|Leland|2010|p=2}} |

|||

* 20,000 captured{{sfnm|Tucker et al.|2012|1p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=hVSrJBQYAk8C&pg=PA311 311]|Hickey|2012n}} |

|||

* 8 frigates captured or burned |

|||

* 1,400 [[merchant ship]]s captured |

|||

* 278 privateers captured |

|||

* 4,000 slaves escaped or freed{{sfn|Weiss|2013}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| casualties2 = {{plainlist| |

|||

* 2,700 died in combat or disease{{sfn|Stagg|2012|p=156}} |

|||

* 10,000 died from all causes{{sfn|Clodfelter|2017|p=245}}{{efn|Includes 2,250 men of the Royal Navy.}} |

|||

* 15,500 captured |

|||

* 4 frigates captured |

|||

* ~1,344 merchant ships captured (373 recaptured){{sfn|Clodfelter|2017|p=244}} |

|||

* 10,000 Indigenous warriors and civilians dead from all causes{{sfn|Clodfelter|2017|p=245}}{{efn|Includes 1,000 combat casualties on the northern front.}} |

|||

* 14 Spanish killed and 6 wounded{{sfn|Owsley|2000|p=118}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| campaignbox = {{Campaignbox War of 1812: St. Lawrence Frontier}}{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Niagara frontier}}{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Old Northwest}}{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Chesapeake campaign}}{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Gulf Theater 1813–1815}}{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Naval}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''War of 1812''' was fought by the [[United States]] and its allies against the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom]] and its allies in [[North America]]. It began when the United States [[United States declaration of war on the United Kingdom|declared war on Britain]] on 18 June 1812. Although peace terms were agreed upon in the December 1814 [[Treaty of Ghent]], the war did not officially end until the peace treaty was ratified by the [[13th United States Congress|United States Congress]] on 17 February 1815.{{sfn|Order of the Senate of the United States|1828|pp=619–620}}{{sfn|Carr|1979|p=276}} |

|||

|combatant2= {{plainlist| |

|||

{{Flagicon|UK}} [[British Empire]] |

|||

* {{Flagicon|UK}} [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom]] |

|||

* {{Flagicon|UK}} [[The Canadas]] |

|||

*[[Tecumseh's Confederacy]] <small>(until 1813)</small><ref>[http://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-the-Thames Battle of the Thames], [[Encyclopædia Britannica]], "Many British troops were captured and Tecumseh was killed, destroying his Indian alliance and breaking the Indian power in the Ohio and Indiana territories. After this battle, most of the tribes abandoned their association with the British."</ref> |

|||

** [[Shawnee]] |

|||

** [[Creek (people)|Creek Red Sticks]] |

|||

** [[Ojibwe]] |

|||

** [[Fox (Native American)|Fox]] |

|||

** [[Iroquois]] |

|||

** [[Miami tribe|Miami]] |

|||

** [[Mingo]] |

|||

** [[Ottawa (tribe)|Ottawa]] |

|||

** [[Kickapoo people|Kickapoo]] |

|||

** [[Lenape|Delaware (Lenape)]] |

|||

** [[Mascouten]] |

|||

** [[Potawatomi]] |

|||

** [[Sauk people|Sauk]] |

|||

** [[Wyandot people|Wyandot]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|Spain|1785}} [[History of Spain (1814–73)|Spain]] <small>(1813)</small> |

|||

**{{flagicon|Spain|1785}} [[Spanish Florida|Florida]]}} |

|||

|commander1= {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[James Madison]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Henry Dearborn]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Jacob Brown]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Winfield Scott]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Andrew Jackson]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Henry Harrison]] |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William H. Winder]] {{POW}} |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[William Hull]] {{POW}} |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} [[Zebulon Pike]]{{KIA}}}} |

|||

|commander2= {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool|Lord Liverpool]] |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[George Prévost|Sir George Prévost]] |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Isaac Brock|Sir Isaac Brock]]{{KIA}} |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Gordon Drummond]] |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Charles de Salaberry]] |

|||

*{{Flagicon|UK}} [[Roger Hale Sheaffe]] |

|||

*{{Flagicon |UK}} [[Robert Ross (British army officer)|Robert Ross]]{{KIA}} |

|||

*{{Flagicon |UK}} [[Edward Pakenham]]{{KIA}} |

|||

*[[Tecumseh]]{{KIA}}}} |

|||

|strength1= {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States|1795}} '''United States''' |

|||

**[[U.S. Army]]: |

|||

***7,000 (at war's start) |

|||

***35,800 (at war's end) |

|||

***[[United States Army Rangers|Rangers]]: 3,049 |

|||

**[[Militia (United States)|Militia]]: 458,463* |

|||

**[[U.S. Marines]] |

|||

**[[U.S. Navy]] and [[Revenue Cutter Service]] (at war's start): |

|||

*** [[Six original United States frigates|Frigates]]: 6 |

|||

*** Other vessels: 14 |

|||

* Native allies: |

|||

**125 Choctaw |

|||

**unknown others{{sfn|Upton|2003}}}} |

|||

|strength2= {{plainlist| |

|||

*{{flagicon|UK}} '''British Empire''' |

|||

**[[British Army]] |

|||

***5,200 (at war's start) |

|||

***48,160 (at war's end) |

|||

**Provincial regulars: 10,000 |

|||

**[[Colonial militia in Canada|Militia]]: 4,000 |

|||

**[[Royal Marines]] |

|||

**[[Royal Navy]] |

|||

***[[Ship of the line|Ships of the line]]: 11 |

|||

***[[Frigate]]s: 34 |

|||

***Other vessels: 52 |

|||

**[[Provincial Marine]] (at war's start):‡ |

|||

***Ships: 9 |

|||

*Native allies: 10,000{{sfn|Allen|1996|p=121}}}} |

|||

|casualties1=2,200 killed in action |

|||

*4,505 wounded |

|||

*15,000 (est.) died from all causes<ref group=lower-alpha>All U.S. figures are from Donald Hickey {{harv|Hickey|2006|p=297}}</ref> |

|||

|casualties2=1,160 killed in action<ref name="historyguy.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.historyguy.com/war_of_1812_statistics.htm|title=War of 1812 Statistics|work=historyguy.com|accessdate=September 4, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

*3,679 wounded |

|||

*3,321 died from disease |

|||

|notes={{plainlist| |

|||

* * Some militias operated in only their own regions. |

|||

*{{KIA}} [[Killed in action]] |

|||

* ‡ A locally raised [[coastal protection]] and seminaval force on the [[Great Lakes]].}}}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: St. Lawrence Frontier}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Niagara frontier}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Old Northwest}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Chesapeake campaign}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: American South}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox War of 1812: Naval}} |

|||

Anglo-American tensions stemmed from long-standing differences over territorial expansion in North America and British support for [[Tecumseh's confederacy]], which resisted U.S. colonial settlement in the [[Old Northwest]]. In 1807, these tensions escalated after the [[Royal Navy]] began enforcing [[Orders in Council (1807)|tighter restrictions]] on American trade with [[First French Empire|France]] and [[Impressment|impressed]] sailors who were originally [[British subject]]s, even those who had acquired [[Citizenship of the United States|American citizenship.]]{{sfn|Hickey|1989|p=44}} Opinion in the U.S. was split on how to respond, and although majorities in both the [[United States House of Representatives|House]] and [[United States Senate|Senate]] voted for war, they were divided along strict party lines, with the [[Democratic-Republican Party]] in favour and the [[Federalist Party]] against.{{efn|The House declared war by 61.7% with a majority in all sections, 20 Members not voting, and the Senate was closer at 59.4%, four not voting. The former Federalist stronghold in Massachusetts had one Democrat-Republican and one Federalist for U.S. Senators, with ten Democrat-Republicans and seven Federalists in the House. Only two states had both Senators in the Federalist Party: Connecticut with 7 Federalist Representatives, and Maryland with 7 Democrat-Republicans and 3 Federalists in the House.}}{{sfn|Hickey|1989|pp=32, 42–43}} News of British concessions made in an attempt to avoid war did not reach the U.S. until late July, by which time the conflict was already underway. |

|||

The '''War of 1812''' was a military conflict that lasted from June 1812 to February 1815, fought between the [[United States|United States of America]] and the [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|United Kingdom]], its [[British North America|North American colonies]], and its [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] allies. Historians in the United States and Canada see it as a war in its own right, but the British often see it as a minor theatre of the [[Napoleonic Wars#War between Britain and France, 1803–1814|Napoleonic Wars]]. By the war's end in early 1815, the key issues had been resolved and peace returned with no boundary changes. |

|||

At sea, the Royal Navy imposed an effective [[blockade]] on U.S. maritime trade, while between 1812 and 1814 [[British Army|British regulars]] and [[Colonial militia in Canada|colonial militia]] defeated a series of American invasions on [[Upper Canada]].{{sfn|Greenspan|2018}} The [[Treaty of Fontainebleau (1814)|April 1814 abdication]] of [[Napoleon]] allowed the British to send additional forces to North America and reinforce the Royal Navy blockade, crippling the [[Economy of the United States|American economy]].{{sfn|Benn|2002|pp=56–57}} In August 1814, negotiations began in [[Ghent]], with both sides wanting peace; the [[Economy of the United Kingdom|British economy]] had been severely impacted by the trade embargo, while the Federalists convened the [[Hartford Convention]] in December to formalize their opposition to the war. |

|||

The United States declared war for several reasons, including trade restrictions brought about by the British war with France, the [[impressment]] of as many as 10,000 American merchant sailors into the [[Royal Navy]],<ref>{{cite book|author=J. C. A. Stagg|title=The War of 1812: Conflict for a Continent|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Wt4gAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA128|year=2012|page=128}}</ref> British support for Native American tribes fighting [[European American]] settlers on the frontier, outrage over insults to national honor during the [[Chesapeake–Leopard Affair]], and interest in the United States in expanding its borders west.{{sfn| Stagg|1983| p=4}} The British government, which felt it had done everything in its power to try to avert the war, were dismayed by the American declaration, and believed it to have been an opportunistic ploy by President Madison to annex Canada while it was fighting a ruinous war with France.<ref>Hansard, ADDRESS RESPECTING THE WAR WITH AMERICA. HC Deb 18 February 1813 vol 24 cc593-649 593 Lord Castlereagh,</ref> <ref>Hansard, Lord Liverpool 5 May 1812</ref> The view was shared in much of New England and for that reason the war was widely referred to there as Mr Madison’s War. As a result, the primary British war goal was to defend their North American colonies. |

|||

In August 1814, British troops [[Burning of Washington|captured Washington]], before American victories at [[Battle of Baltimore|Baltimore]] and [[Battle of Plattsburgh|Plattsburgh]] in September ended fighting in the north. In the [[Southeastern United States]], American forces and Indian allies [[Creek War|defeated]] an [[Red Sticks|anti-American faction]] of the [[Muscogee]]. In early 1815, American troops led by Andrew Jackson repulsed a major British attack on [[Battle of New Orleans|New Orleans]], which occurred during the ratification process of the signing of the [[Treaty of Ghent]], which brought an end to the conflict.<ref>{{Cite web |title= The Senate Approves for Ratification the Treaty of Ghent |url=https://www.senate.gov/about/powers-procedures/treaties/senate-approves-treaty-of-ghent.htm#:~:text=On%20January%208,%201815,%20unaware,treaty,%20prompting%20great%20public%20celebrations. |access-date=2024-01-03 |website=U.S. Senate }}</ref> |

|||

The war was fought in three theatres. First, at sea, warships and [[privateer]]s of each side attacked the other's merchant ships, while the British [[blockade]]d the Atlantic coast of the United States and mounted large raids in the later stages of the war. Second, land and naval battles were fought on the U.S.–Canadian frontier. Third, large-scale battles were fought in the [[Southern United States]] and Gulf Coast. At the end of the war, both sides signed and ratified the [[Treaty of Ghent]] and, in accordance with the treaty, returned occupied land, prisoners of war and captured ships (with the exception of warships due to frequent re-commissioning upon capture) to their pre-war owners and resumed friendly trade relations without restriction. |

|||

== Origins == |

|||

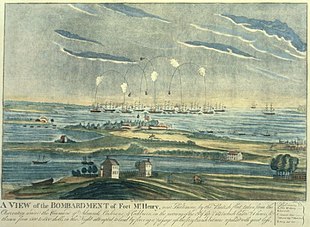

With the majority of its land and naval forces tied down in Europe fighting the Napoleonic Wars, the British used a defensive strategy until 1814. Early victories over poorly-led U.S. armies demonstrated that the conquest of the Canadas would prove more difficult than anticipated. Despite this, the U.S. was able to inflict serious defeats on Britain's Native American allies, ending the prospect of an independent [[Tecumseh's Confederacy|Indian confederacy]] in the Midwest under British sponsorship. U.S. forces took control of [[Lake Erie]] in 1813, and seized western parts of [[Upper Canada]], but further American offensives aimed at Montreal failed, and the war also degenerated into a stalemate in Upper Canada by 1814. In April 1814, with the defeat of Napoleon, Britain now had large numbers of spare troops and adopted a more aggressive strategy, launching invasions of the United States; however, an invasion of New York was defeated at [[Battle of Plattsburgh|Plattsburgh]], and a second force, although successfully [[Burning of Washington|capturing Washington]], was ultimately repulsed during [[Battle of Fort McHenry|an attack on Baltimore]]. Both governments were eager for a return to normality and peace negotiations began in Ghent in August 1814. These repulses led Britain to drop demands for a native buffer state and some territorial claims, and peace was finally signed in December 1814, although news failed to arrive before the British suffered a major defeat at [[Battle of New Orleans|New Orleans]] in January 1815.<ref>Hitsman, p. 270.</ref> |

|||

{{Excerpt|Origins of the War of 1812}} |

|||

== Forces == |

|||

=== American === |

|||

During the years 1810–1812, American naval ships were divided into two major squadrons, with the "northern division", based at New York, commanded by Commodore John Rodgers, and the "southern division", based at Norfolk, commanded by Commodore Stephen Decatur.{{sfn|Crawford|Dudley|1985|p=40}} |

|||

Although not much of a threat to Canada in 1812, the United States Navy was a well-trained and professional force comprising over 5,000 sailors and marines.{{sfn|Grodzinski|2013|p=69}} It had 14 ocean-going warships with three of its five "super-frigates" non-operational at the onset of the war.{{sfn|Grodzinski|2013|p=69}} Its principal problem was lack of funding, as many in Congress did not see the need for a strong navy.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} The biggest ships in the American navy were frigates and there were no [[ship of the line|ships-of-the-line]] capable of engaging in a [[fleet action]] with the Royal Navy.{{sfn|Benn|2002|pp=20–21}} On the high seas, the Americans pursued a strategy of [[commerce raiding]], capturing or sinking British [[merchant ships|merchantmen]] with their frigates and privateers.{{sfn|Benn|2002|pp=20 & 54–55}} The Navy was largely concentrated on the Atlantic coast before the war as it had only two [[gunboat]]s on [[Lake Champlain]], one [[brig]] on Lake Ontario and another brig in Lake Erie when the war began.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} |

|||

In the United States, late victories over invading British armies at the battles of Plattsburgh, Baltimore (inspiring the United States national anthem, "[[The Star-Spangled Banner]]") and New Orleans produced a sense of euphoria over a "second war of independence" against Britain.{{sfn|Langguth|2006}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/madison/aa_madison_war_1.html |title=Second War of American Independence |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=2000 |website=America's Library |publisher=Library of Congress |accessdate=December 25, 2015}}</ref> This brought an "[[Era of Good Feelings]]" in which partisan animosity nearly vanished in the face of strengthened [[American nationalism]]. The war was also a major turning point in the development of the [[U.S. military]], with militia being increasingly replaced by a more professional force. The U.S. also acquired permanent ownership of Spain's [[Mobile District]], although Spain was not a belligerent. |

|||

The [[United States Army]] was initially much larger than the [[British Army]] in North America. Many men carried their own [[long rifle]]s while the British were issued [[musket]]s, except for one unit of 500 riflemen. Leadership was inconsistent in the American officer corps as some officers proved themselves to be outstanding, but many others were inept, owing their positions to political favours. Congress was hostile to a [[standing army]] and the government called out 450,000 men from the [[state defense force|state militias]] during the war.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} The [[Militia (United States)|state militias]] were poorly trained, armed, and led. The failed invasion of Lake Champlain led by General Dearborn illustrates this.{{sfn|Barney|2019}} The British Army soundly defeated the Maryland and Virginia militias at the [[Battle of Bladensburg]] in 1814 and President Madison commented "I could never have believed so great a difference existed between regular troops and a militia force, if I had not witnessed the scenes of this day".{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} |

|||

In Upper and Lower Canada, British and [[Canadian units of the War of 1812|local Canadian militia]] victories over invading U.S. armies became [[Results of the War of 1812#Canada|iconic]] and promoted the development of a distinct Canadian identity, which included strong loyalty to Britain. Today, particularly in Ontario, memory of the war retains significance, because the defeat of the invasions ensured that the Canadas would remain part of the British Empire, rather than be annexed by the United States. The government of Canada declared a three-year commemoration of the War of 1812 in 2012,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://canada.pch.gc.ca/eng/1442339111871/1442339533102 |title=War of 1812 - About the Commemoration |author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date=2012 |website=Government of Canada |publisher=Government of Canada |access-date=June 5, 2016 |quote=In 2012, Canada began a three-year commemoration of the War of 1812, an important milestone in the lead-up to the 150th anniversary of Canada's Confederation in 2017.}}</ref> intended to offer historical lessons and celebrate 200 years of peace across the border.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pc.gc.ca/voyage-travel/provinces/intro-ontario/1812.aspx|title=Parks Canada War of 1812 Ceremonies|publisher=Government of Canada|accessdate=2013-01-01}}</ref> At the conclusion of the bicentennial commemorations in 2014, a new national [[War of 1812 Monument]] was unveiled in Ottawa. |

|||

=== British === |

|||

[[File:War of 1812 Re-enactment, Battle of Stoney Creek (ontario); June 2016.jpg|thumb|Re-enactors (in UK uniforms) fire muskets toward the "Americans" in this annual commemoration of the June 6, 1813 Battle of Stoney Creek]] |

|||

{{see also|Canadian units of the War of 1812}} |

|||

The conflict has not been commemorated on nearly the same level in the modern-day United States, though it is still taught as an important part of early American history,<ref>"[http://www.npr.org/2012/06/18/155308632/teaching-the-war-of-1812-different-in-u-s-canada Teaching The War Of 1812 Different In U.S., Canada]." NPR.com. 2012-06-18. Retrieved 2015-10-05.</ref> and [[Dolley Madison]] and [[Andrew Jackson]]'s respective roles in the war are especially emphasized.<ref>Fleming, Thomas. "[http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-dolley-madison-saved-the-day-7465218/?no-ist When Dolley Madison Took Command of the White House]". Smithsonian Magazine. March 2010. Retrieved 2015-10-05.</ref><ref>"[http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/jackson-leads-troops-to-victory-at-new-orleans Jackson leads troops to victory at New Orleans]". History Channel. Retrieved 2015-10-05.</ref> The war is scarcely remembered in Britain, being heavily overshadowed by the much larger Napoleonic Wars occurring in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/wned/war-of-1812/essays/british-perspective/ |title= A British Perspective on the War of 1812 |publisher= PBS |accessdate=2016-05-30}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:100th Regiment of Foot c1812-1814.jpg|thumb|Depiction of a British private soldier (left) and officer (right) of the period]] |

|||

The United States was only a secondary concern to Britain, so long as the [[Napoleonic Wars]] continued with France.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line and was building another 35. Containing the French fleet was the main British naval concern,{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} leaving only the ships on the [[North America and West Indies Station|North American]] and [[Jamaica Station (Royal Navy)|Jamaica]] Stations immediately available. In Upper Canada, the British had the [[Provincial Marine]]. While largely unarmed,{{sfn|Crawford|Dudley|1985|p=268}} they were essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads were abysmal in Upper Canada.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} At the onset of war, the Provincial Marine had four small armed vessels on [[Lake Ontario]], three on [[Lake Erie]] and one on Lake Champlain. The Provincial Marine greatly outnumbered anything the Americans could bring to bear on the Great Lakes.{{sfn|Caffrey|1977|p=174}} |

|||

When the war broke out, the British Army in North America numbered 9,777 men{{sfn|Hitsman|1965|p=295}} in regular units and [[Fencibles#War of 1812|fencibles]].{{efn|units raised for local service but otherwise on the same terms as regulars}} While the British Army was engaged in the [[Peninsular War]], few reinforcements were available. Although the British were outnumbered,{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} the long-serving regulars and fencibles were better trained and more professional than the hastily expanded United States Army.{{sfn|Elting|1995|p=11}} The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada were initially far less effective,{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} but substantial numbers of full-time militia were raised during the war and played pivotal roles in several engagements, including the [[Battle of the Chateauguay]] which caused the Americans to abandon the Saint Lawrence River theatre.{{sfnm|Benn|2002|1p=21|Ingersoll|1845|2pp=297–299}} |

|||

==Origins== |

|||

{{Main article|Origins of the War of 1812}} |

|||

Historians have long debated the relative weight of the multiple reasons underlying the origins of the War of 1812. This section summarizes several contributing factors which resulted in the declaration of war by the United States.{{sfnm|1a1=Trautsch|1y=2013|1pp=273–293|2a1=Egan|2y=1974|3a1=Goodman|3y=1941|3pp=171–186}}<ref>{{cite book|author=Scott A. Silverstone|title=Divided Union: The Politics of War in the Early American Republic|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PdOuJ6FG1K0C&pg=PA95|year=2004|publisher=Cornell University Press|page=95}}</ref> |

|||

=== Indigenous peoples === |

|||

===Honour and the second war of independence=== |

|||

The highly decentralized bands and tribes considered themselves allies of, and not subordinates to, the British or the Americans. Various tribes fighting with United States forces provided them with their "most effective light troops"{{sfn|Carstens|Sanford|2011|p=53}} while the British needed Indigenous allies to compensate for their numerical inferiority. The Indigenous allies of the British, [[Tecumseh's confederacy]] in the west and [[Iroquois]] in the east, avoided pitched battles and relied on [[irregular warfare]], including raids and ambushes that took advantage of their knowledge of terrain. In addition, they were highly mobile, able to march {{convert|30|–|50|miles|-1}} a day.{{sfn|Starkey|2002|p=18}} |

|||

As Risjord (1961) notes, a powerful motivation for the Americans was the desire to uphold national honour in the face of what they considered to be British insults such as the [[Chesapeake–Leopard Affair]].{{sfn|Risjord|1961|pp=196–210}} Brands says, "The other war hawks spoke of the struggle with Britain as a second war of independence; [Andrew] Jackson, who still bore scars from the first war of independence held that view with special conviction. The approaching conflict was about violations of American rights, but it was also about vindication of American identity".{{sfn|Brands|2006|p=163}} Americans at the time and historians since often called it the United States' "Second War of Independence".<ref>Hickey, Donald R. ed.''The War of 1812: Writings from America's Second War of Independence'' (2013).</ref> |

|||

Their leaders sought to fight only under favourable conditions and would avoid any battle that promised heavy losses, doing what they thought best for their tribes.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} The Indigenous fighters saw no issue with withdrawing if needed to save casualties. They always sought to surround an enemy, where possible, to avoid being surrounded and make effective use of the terrain.{{sfn|Starkey|2002|p=18}} Their main weapons were a mixture of muskets, rifles, bows, [[tomahawk]]s, knives and swords as well as clubs and other melee weapons, which sometimes had the advantage of being quieter than guns.{{sfn|Starkey|2002|p=20}} |

|||

===Trade with France=== |

|||

In 1807, Britain introduced a series of trade restrictions via a [[Orders in Council (1807)|series of Orders in Council]] to impede neutral trade with [[First French Empire|France]], with which Britain was at war. The United States contested these restrictions as illegal under international law.<ref name="Fanis2011">{{cite book|author=Maria Fanis|title=Secular Morality and International Security: American and British Decisions about War|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WJ1T2eEE94gC&pg=PA49|year=2011|publisher=U. of Michigan Press|page=49|isbn=0472117556}}</ref> Also, historian Reginald Horsman states, "a large section of influential British opinion, both in the government and in the country, thought that America presented a threat to British maritime supremacy".{{sfn|Horsman|1962|p=264}} |

|||

== Declaration of war == |

|||

The American merchant marine had come close to doubling between 1802 and 1810, making it by far the largest neutral fleet. Britain was the largest trading partner, receiving 80% of U.S. cotton and 50% of other U.S. exports. The British public and press were resentful of the growing mercantile and commercial competition.{{sfn|Toll|2006|p=281}} The United States' view was that Britain's restrictions violated its right to trade with others. |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

| align = right |

|||

===Impressment and Naval actions=== |

|||

| direction = horizontal |

|||

[[File:Luke Clennell02.jpg|thumb|Press gang: oil painting by [[Luke Clennell]]]] |

|||

| image1 = 1812 War Declaration.jpg |

|||

During the [[Napoleonic Wars]], the [[Royal Navy]] expanded to 176 [[Ship of the line|ships of the line]] and 600 ships overall, requiring 140,000 sailors to man.{{sfn|Toll|2006|p=382}} While the Royal Navy could man its ships with volunteers in peacetime, it competed in wartime with [[British Merchant Navy|merchant shipping]] and [[privateer]]s for a small pool of experienced sailors and turned to [[impressment]] from ashore and foreign or domestic shipping when it could not operate its ships with volunteers alone. |

|||

| width1 = 159 |

|||

| footer = The United States Declaration of War (left) and [[Isaac Brock]]'s Proclamation in response to it (right) |

|||

The United States believed that British deserters had a right to become [[Citizenship in the United States|U.S. citizens]]. Britain did not recognize a right whereby a British subject could relinquish his status as a British subject, emigrate and transfer his national allegiance as a naturalized citizen to any other country. This meant that in addition to recovering naval deserters, it considered any United States citizens who were born British liable for impressment. Aggravating the situation was the reluctance of the United States to issue formal naturalization papers and the widespread use of unofficial or forged identity or [[protection papers]] by sailors.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Rodger |first1=N. A. M. |author-link1=Nicholas A. M. Rodger |title=Command of the Ocean |location=London |publisher=Penguin Books |publication-date=2005 |pages=565–566 |isbn=0-140-28896-1 }}</ref> This made it difficult for the Royal Navy to distinguish Americans from non-Americans and led it to impress some Americans who had never been British. (Some gained freedom on appeal).{{sfn|Latimer|2007|p=17}}Thus while the United States recognized British-born sailors on American ships as Americans, Britain did not. It was estimated by the Admiralty that there were 11,000 [[Naturalization|naturalized]] sailors on United States ships in 1805. U.S. Secretary of the Treasury [[Albert Gallatin]] stated that 9,000 U.S. sailors were born in Britain.<ref>{{harvnb|Caffrey|1977|p=60}}</ref> Moreover, a great number of these British born sailors were Irish. For instance an investigation by Captain [[Isaac Chauncey]] in 1808 found that 58% of sailors based in New York City were either naturalized citizens or recent immigrants, the majority of these foreign born sailors (134 of 150) being from Britain. Moreover, 80 of the 134 British sailors were Irish. |

|||

| image2 = Proclamation Province of Upper Canada by Isaac Brock.jpg |

|||

| width2 = 140 |

|||

American anger at impressment grew when British frigates were stationed just outside U.S. harbours in view of U.S. shores and searched ships for contraband and impressed men while within U.S. territorial waters.{{sfn|Toll|2006|pp=278–279}} Well publicized impressment actions such as the [[HMS Leander (1780)#The Leander Affair|''Leander'' Affair]] and the [[Chesapeake–Leopard Affair|''Chesapeake''–''Leopard'' Affair]] outraged the American public.{{sfn|Black|2002|p=44}} {{sfn|Taylor|2010|p=104}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The British public in turn were outraged by the [[Little Belt Affair|''Little Belt'' Affair]], in which a larger American ship clashed with a small British sloop, resulting in the deaths of 11 British sailors. Both sides claimed the other fired first, but the British public in particular blamed the US for attacking a smaller vessel, with calls for revenge by some newspapers,<ref>Hooks, J. "Redeemed honor: the President-Little Belt Affair and the coming of the war of 1812" The Historian, (1), 1 (2012)</ref><ref>Donald Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict (Chicago, IL, 1989). p22</ref> while the US was encouraged by the fact they had won a victory over the Royal Navy.<ref>Hooks, J. W. (2009). “A friendly salute the President-Little Belt Affair and the coming of the war of 1812” Ebscohost P ii</ref> The U.S. Navy also forcibly recruited British sailors but the British government saw impressment as commonly accepted practice and preferred to rescue British sailors from American impressment on a case-by-case basis.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2012/summer/1812-impressment.html|title=John P. Deeben, "The War of 1812 Stoking the Fires: The Impressment of Seaman Charles Davis by the U.S. Navy", ''Prologue Magazine'', U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Summer 2012, Vol. 44, No. 2|date=October 26, 2012|publisher=|accessdate=October 1, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

===British support for Native American raids=== |

|||

{{Warof1812-Origins}} |

|||

The [[Northwest Territory]], comprising the modern states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, was the battleground for conflict between the Native American Nations and the United States.{{sfn|White|2010|p=416}} The British Empire had ceded the area to the United States in the [[Treaty of Paris (1783)|Treaty of Paris]] in 1783, both sides ignoring the fact that the land was already inhabited by various Native American nations. These included the [[Miami people|Miami]], [[Winnebago people|Winnebago]], [[Shawnee people|Shawnee]], [[Fox people|Fox]], [[Sauk people|Sauk]], [[Kickapoo people|Kickapoo]], [[Lenape|Delaware]] and [[Wyandot people|Wyandot]]. Some warriors, who had left their nations of origin, followed [[Tenskwatawa]], the Shawnee Prophet and the brother of [[Tecumseh]]. Tenskwatawa had a vision of purifying his society by expelling the "children of the Evil Spirit": the American settlers.{{sfn|Willig|2008|p=207}} The Indians wanted to create their own state in the Northwest, which end the American threat forever as it became clear that the Americans wanted all of the land in the Old Northwest for themselves.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=18}} Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh formed a confederation of numerous tribes to block American expansion. The British saw the Native American nations as valuable allies and a buffer to its Canadian colonies and provided arms. Attacks on American settlers in the Northwest further aggravated tensions between Britain and the United States.{{sfn|Hitsman|1965|p=27}} Raiding grew more common in 1810 and 1811; Westerners in Congress found the raids intolerable and wanted them permanently ended.{{sfnm|1a1=Heidler|1a2=Heidler|1y=1997|1pp=253, 504|2a1=Zuehlke|2y=2007|2p=62}} British policy towards the Indians of the Northwest was torn between on one point the desire to keep the Americans fighting in the Northwest and to preserve a region that provided rich profits for Canadian fur traders vs. the fear of too much support for the Indians would cause a war with the United States.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=18}} Through Tecumseh's plans for an Indian state in the Northwest would benefit British North America by making it more defensible, at the same time, the defeats suffered by Tecumseh's confederation had the British leery to going too far to support what was probably a losing cause and in the months running to the war, British diplomats attempted to defuse tensions on the frontier.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=18}} |

|||

The confederation's raids and existence hindered American expansion into rich farmlands in the Northwest Territory.{{sfn|Heidler|Heidler|1997|pp=253, 392}} Pratt writes: |

|||

{{quote|There is ample proof that the British authorities did all in their power to hold or win the allegiance of the Indians of the Northwest with the expectation of using them as allies in the event of war. Indian allegiance could be held only by gifts, and to an Indian no gift was as acceptable as a lethal weapon. Guns and ammunition, tomahawks and scalping knives were dealt out with some liberality by British agents.{{sfn|Pratt|1955|p=126}}}} |

|||

However, according to the U.S Army Center of Military History, the "land-hungry frontiersmen", with "no doubt that their troubles with the Native Americans were the result of British intrigue", exacerbated the problem by {{nowrap|"[circulating}} stories] after every Native American raid of British Army muskets and equipment being found on the field". Thus, "the westerners were convinced that their problems could best be solved by forcing the British out of Canada".<ref name="http://www.history.army.mil.htm">{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://www.history.army.mil/books/AMH/AMH-06.htm |

|||

|title = American Military History, Army Historical Series, Chapter 6 |publisher = |accessdate= 2013-07-01}}</ref> |

|||

The British had the long-standing goal of creating a large "neutral" Native American state that would cover much of Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. They made the demand as late as the fall of 1814 at the peace conference, but lost control of western Ontario in 1813 at key battles on and around Lake Erie. These battles destroyed the [[Tecumseh's Confederacy|Indian confederacy]] which had been the main ally of the British in that region, weakening its negotiating position. Although the area remained under British or British-allied Native Americans' control until the end of the war, the British, at American insistence and with higher priorities, dropped the demands.{{sfnm|1a1=Smith|1y=1989|1pp=46–63, esp. pp. 61–63|2a1=Carroll|2y=2001|2p=23}} |

|||

===American expansionism=== |

|||

American expansion into the Northwest Territory was being obstructed by indigenous leaders such as [[Tecumseh]], who were supplied and encouraged by the British. Americans on the western frontier demanded that interference be stopped.{{sfn|Kennedy|Cohen|Bailey|2010|p=244}} There is dispute, however, over whether or not the American desire to annex Canada brought on the war. Several historians believe that the capture of Canada was intended only as a means to secure a bargaining chip, which would then be used to force Britain to back down on the maritime issues. It would also cut off food supplies for Britain's West Indian colonies, and temporarily prevent the British from continuing to arm the Indians.{{sfn|Bowler|1988|pp=11–32}}{{sfnm|1a1=Stagg|1y=1981|1pp=3–34|2a1=Stagg|2y=1983|2loc={{page needed|date=September 2010}}|3a1=Horsman|3y=1962|3p=267|4a1=Hickey|4y=1989|4p=72|5a1=Brown|5y=1971|5p=128|6a1=Burt|6y=1940|6pp=305–310|7a1=Stuart|7y=1988|7p=76}} However, many historians believe that a desire to annex Canada was a cause of the war. This view was more prevalent before 1940, but remains widely held today.<ref>George F. G. Stanley, 1983, pg. 32 {{full citation needed|date=July 2013}}</ref><ref>David Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler, The War of 1812, pg4 {{full citation needed|date=June 2013}}<!--needs a date--></ref>{{sfnm|1a1=Pratt|1y=1925|1pp=9–15|2a1=Hacker|2y=1924|2pp=365–395|3a1=Hickey|3y=1989|3p=47|4a1=Carlisle|4a2=Golson|4y=2007|4p=44|5a1=Stagg|5y=2012|5pp=5–6|6a1=Tucker|6y=2011|6p=236|7a1=Nugent|7y=|7p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=_zDQlAp4T4wC&lpg=PA75&vq=The%20American%20yearning&pg=PA75#v=snippet&q=Expansion%20was%20not%20the%20only%20American%20objective&f=false 73–75]}}<ref>"War of 1812–1815 (Milestones 1801–1829). US Department of State, Office of the Historian, Web. 26 Apr. 2016</ref> Congressman [[Richard Mentor Johnson]] told Congress that the constant Indian atrocities along the Wabash River in Indiana were enabled by supplies from Canada and were proof that "the war has already commenced. ... I shall never die contented until I see England's expulsion from North America and her territories incorporated into the United States."<ref>Langguth, ''Union 1812'', p. 262.</ref> |

|||

Madison believed that British economic policies designed to foster imperial preference were harming the American economy and that as British North America existed, here was a conduit for American strugglers who were undercutting his trade policies, which thus required that the United States annex British North America.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=16}} Furthermore, Madison believed that the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence trade route might become the main trade route for the export of North American goods to Europe at the expense of the U.S. economy, and if the United States controlled the resources of British North America like timber which the British needed for their navy, then Britain would be forced to change its maritime policies which had so offended American public opinion.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=16}} Many Americans believed it was only natural that their country should shallow up North America with one Congressman, John Harper saying in a speech that "the Author of Nature Himself had marked our limits in the south, by the Gulf of Mexico and on the north, by the regions of eternal frost".{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=16}} [[Upper Canada]] (modern southern Ontario) had been settled mostly by Revolution-era exiles from the United States ([[United Empire Loyalist]]s) or postwar American immigrants. The Loyalists were hostile to union with the United States, while the immigrant settlers were generally uninterested in politics and remained neutral or supported the British during the war. The Canadian colonies were thinly populated and only lightly defended by the British Army. Americans then believed that many men in Upper Canada would rise up and greet an American invading army as liberators. That did not happen. One reason American forces retreated after one successful battle inside Canada was that they could not obtain supplies from the locals.{{sfn|Berton|2001|p=206}} But the Americans thought that the possibility of local support suggested an easy conquest, as former President [[Thomas Jefferson]] believed: "The acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching, and will give us the experience for the attack on Halifax, the next and final expulsion of England from the American continent".{{sfn|Hickey|2012|p=68}} |

|||

Annexation was supported by American border businessmen who wanted to gain control of Great Lakes trade.<ref>{{harvnb|Nugent|p=75}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:James Madison.jpg|thumb|upright|[[James Madison]], U.S. President, (1809–1817)]] |

|||

[[File:Lord Liverpool.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool|Lord Liverpool]], British Prime Minister, (1812–1827)]] |

|||

Carl Benn noted that the War Hawks' desire to annex the Canadas was similar to the enthusiasm for the annexation of [[Spanish Florida]] by inhabitants of the American South; both expected war to facilitate expansion into long-desired lands and end support for hostile Indian tribes (Tecumseh's Confederacy in the North and the Creek in the South).<ref>Benn, C., & Marston, D. (2006). Liberty or death: Wars that forged a nation. Oxford: Osprey Pub.</ref> |

|||

Stagg has examined the fate of the expansionist cause proposed by Hacker and Pratt in the 1920s: |

|||

{{quote|this 'expansionist' interpretation of the war can still be found in textbooks currently in use in the nation's high schools. It has also compounded popular confusion about the war by perpetuating an arid dispute over what should be deemed to be its 'real' or most important causes. Were these causes international or domestic in origin? That debate became both interminable and insoluble. Consequently, a new generation of historians by the 1960s ... repudiated the views of Hacker and Pratt.{{sfn|Stagg|2012|pp=5-6}}}} |

|||

Southern Congressman [[Felix Grundy]] considered it essential to acquire Canada to ''preserve'' domestic political balance, arguing that annexing Canada would maintain the free state-slave state balance, which might otherwise be thrown off by the acquisition of Florida and the settlement of the southern areas of the new [[Louisiana Purchase]].<ref>{{cite book|author=John Roderick Heller|title=Democracy's Lawyer: Felix Grundy of the Old Southwest|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u8mM8D9RVu4C&pg=PA98|year=2010|page=98}}</ref> However historian Richard Maass argued in 2015 that the expansionist theme is a myth that goes against the "relative consensus among experts that the primary U.S. objective was the repeal of British maritime restrictions". He argues that consensus among scholars is that the United States went to war "because six years of economic sanctions had failed to bring Britain to the negotiating table, and threatening the Royal Navy's Canadian supply base was their last hope." Maass agrees that theoretically expansionism might have tempted Americans, but finds that "leaders feared the domestic political consequences of doing so. Notably, what limited expansionism there was focused on sparsely populated western lands rather than the more populous eastern settlements [of Canada]."<ref>Richard W. Maass, "Difficult to Relinquish Territory Which Had Been Conquered": Expansionism and the War of 1812", ''Diplomatic History'' (Jan 2015) 39#1 pp 70–97 doi: 10.1093/dh/dht132 [http://dh.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2014/01/06/dh.dht132.short Abstract Online]</ref> |

|||

Horsman argued expansionism played a role as a secondary cause after maritime issues, noting that many historians have mistakenly rejected expansionism as a cause for the war. He notes that it was considered key to maintaining sectional balance between free and slave states thrown off by American settlement of the Louisiana Territory, and widely supported by dozens of War Hawk congressmen such as John A. Harper, Felix Grundy, Henry Clay, and Richard M. Johnson, who voted for war with expansion as a key aim. {{quote|In disagreeing with those interpretations that have simply stressed expansionism and minimized maritime causation, historians have ignored deep-seated American fears for national security, dreams of a continent completely controlled by the republican United States, and the evidence that many Americans believed that the War of 1812 would be the occasion for the United States to achieve the long-desired annexation of Canada ... Thomas Jefferson well-summarized American majority opinion about the war ... to say "that the cession of Canada ... must be a [[sine qua non]] [i.e. indispensable condition] at a treaty of peace".<ref name=Horsman87>Horsman, R.. (1987). On to Canada: Manifest Destiny and United States Strategy in the War of 1812. Michigan Historical Review, 13(2), 1–24. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20173101</ref>}} |

|||

However, Horsman states that in his view "the desire for Canada did not cause the War of 1812" and that "The United States did not declare war because it wanted to obtain Canada, but the acquisition of Canada was viewed as a major collateral benefit of the conflict."<ref name=Horsman87/> |

|||

Alan Taylor argues that many Republican congressmen, such as [[Richard M. Johnson]], [[John A. Harper]] and [[Peter B. Porter]], "longed to oust the British from the continent and to annex Canada". Southern Republicans largely opposed this, fearing an imbalance of free and slave states if Canada was annexed, while [[Anti-Catholicism in the United States|anti-Catholicism]] also caused many to oppose annexing mainly Catholic Lower Canada, believing its French-speaking inhabitants "unfit ... for republican citizenship". Even major figures such as [[Henry Clay]] and [[James Monroe]] expected to keep at least Upper Canada in the event of an easy conquest. Notable American generals, like [[William Hull]] were led by this sentiment to issue proclamations to Canadians during the war promising republican liberation through incorporation into the United States; a proclamation the government never officially disavowed. General [[Alexander Smyth]] similarly declared to his troops that when they invaded Canada "You will enter a country that is to become one of the United States. You will arrive among a people who are to become your fellow-citizens." A lack of clarity about American intentions undercut these appeals, however.<ref>{{cite book |last=Taylor |first=Alan |date= 2010 |title= The Civil War of 1812 |url= |location= |publisher= Random House |pages=137–139 |isbn=978-0-679-77673-4}}</ref> |

|||

David and Jeanne Heidler argue that "Most historians agree that the War of 1812 was not caused by expansionism but instead reflected a real concern of American patriots to defend United States' neutral rights from the overbearing tyranny of the British Navy. That is not to say that expansionist aims would not potentially result from the war."<ref>{{cite book|author1=David Stephen Heidler|author2=Jeanne T. Heidler|title=Manifest Destiny|year=2003|publisher=Greenwood Press|page=9}}</ref> |

|||

However, they also argue otherwise, saying that "acquiring Canada would satisfy America's expansionist desires", also describing it as a key goal of western expansionists, who, they argue, believed that "eliminating the British presence in Canada would best accomplish" their goal of halting British support for Indian raids. They argue that the "enduring debate" is over the relative importance of expansionism as a factor, and whether "expansionism played a greater role in causing the War of 1812 than American concern about protecting neutral maritime rights."<ref>David Heidler, Jeanne T. Heidler, ''The War of 1812'' (2002) pg. 4,</ref> |

|||

===U.S. political conflict=== |

|||

{{main article|Federalist Party|Opposition to the War of 1812 in the United States}} |

|||

While the British government was largely oblivious to the deteriorating North American situation because of its involvement in a continent-wide European War, the U.S. was in a period of significant political conflict between the [[Federalist Party]] (based mainly in the Northeast), which favoured a strong central government and closer ties to Britain, and the [[Democratic-Republican Party]] (with its greatest power base in the South and West), which favoured a weak central government, preservation of states' rights (including slavery), expansion into Indian land, and a stronger break with Britain. By 1812, the Federalist Party had weakened considerably, and the Republicans, with James Madison completing his first term of office and control of Congress, were in a strong position to pursue their more aggressive agenda against Britain.<ref>The American political background is detailed by Alan Taylor {{harv|Taylor|2010}}.</ref> Throughout the war, support for the U.S. cause was weak (or sometimes non-existent) in Federalist areas of the Northeast. Few men volunteered to serve; the banks avoided financing the war. The negativism of the Federalists, especially as exemplified by the [[Hartford Convention]] of 1814–15 ruined its reputation and the Party survived only in scattered areas. By 1815 there was broad support for the war from all parts of the country. This allowed the triumphant Republicans to adopt some Federalist policies, such as a national bank, which Madison reestablished in 1816.<ref>Donald R. Hickey, "Federalist Party Unity and the War of 1812." ''Journal of American Studies'' (1978) 12#1 pp. 23–39.</ref><ref>James M. Banner, ''To the Hartford Convention: The Federalists and the Origins of Party Politics in Massachusetts, 1789–1815'' (1970).</ref> |

|||

==Forces== |

|||

===American=== |

|||

The United States Navy (USN) had 7,250 sailors and marines in 1812.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} The American Navy was well trained and a professional force that fought well against the Barbary pirates and France in the Quasi-War.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} The USN had 13 ocean-going warships, three of them "super-frigates" and its principal problem was a lack of funding as many in Congress did not see the need for a strong navy.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} The American warships were all well-built ships that were equal, if not superior to British ships of a similar class (British shipbuilding emphasized quantity over quality). However, the biggest ships in the USN were frigates and the Americans had no ships-of-the-line capable of engaging in a fleet action with the Royal Navy at sea. On the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, the Americans constructed lake fleets which, both in 1813 and 1814, won pivotal battles on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain which forced British withdrawals from American territory.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20-21}} |

|||

On the high seas, the Americans could only pursue a strategy of [[Commerce raiding|''guerre de course'']] of taking British merchantmen via their frigates and privateers.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20 & 54-55}} Before the war, the USN was largely concentrated on the Atlantic coast and at the war's outbreak had only two gunboats on Lake Champlain, one brig on Lake Ontario and another brig in Lake Erie.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} |

|||

The United States Army was much larger than the British Army in North America, but leadership in the American officer corps was inconsistent with some officers proving themselves to be outstanding but many others inept, owing their positions to political favors.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} American soldiers were well trained and brave, but in the early battles were often led by officers of questionable ability.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} Congress was hostile to a standing army, and during the war, the U.S. government called out 450,000 men from the state militas, a number that was slightly smaller than the entire population of British North America.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} However, the state militias were poorly trained, armed and led. After the [[Battle of Bladensburg]] in 1814 in which the Maryland and Virginia militias were soundly defeated by the British Army, President Madison commented: "I could never have believed so great a difference existed between regular troops and a militia force, if I not witnessed the scenes of this day".{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=20}} |

|||

===British=== |

|||

The British Royal Navy was a well-led, professional force, described by the Canadian historian Carl Benn as the world's most powerful navy. However, as long as the war with France continued, North America was a secondary concern.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} In 1813, France had 80 ships-of-the-line while building another 35. Therefore, containing the French fleet had to be the main British naval concern.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} In Upper Canada, the British had the Provincial Marine was essential for keeping the army supplied since the roads in Upper Canada were abysmal.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} On Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence, the Royal Navy had two schooners while the Provincial Marine maintained four small warships on Lake Erie.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} |

|||

The British Army in North America was a very professional and well trained force, but suffered from being outnumbered.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} Regular regiments from Great Britain were bolstered by the so-called "Fencible" regiments which, while regular units of the British Army, were recruited from the North American colonies exclusively for service within North America. Regular units were well trained but spread thinly particularly in Upper Canada where only 1,600 regulars were available at the start of the conflict. <ref> http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/war-of-1812/</ref> |

|||

The militias of Upper Canada and Lower Canada had a much more lower level of military effectiveness.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=21}} Nevertheless, Canadian militia were often more reliable than their American counterparts, particularly when defending their own territory. Main Article: [[Canadian Units of the War of 1812]] |

|||

===Indian=== |

|||

The majority of First Nations in northern North America allied themselves with the British early in the conflict, either due to a recent history of steady American encroachment on their territory south of the border or to defend their own traditional territories in Canada. |

|||

Due to their lower population compared to whites, and lacking artillery, the Indian allies of the British avoided pitched battles and instead relied on irregular warfare, including raids and ambushes.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} Given their low population, it was crucial to avoid heavy losses and, in general, Indian chiefs would seek to only fight under favorable conditions; any battle that promised heavy losses was avoided if possible.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} The main Indian weapons were a mixture of tomahawks, knives, swords, rifles, clubs, arrows and muskets.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} Indian warriors were brave, but the need to avoid heavy losses meant that they would only fight under the most favorable conditions and their tactics favored a defensive as opposed to offensive style.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} |

|||

In the words of Benn, those Indians fighting with the Americans provided the U.S with their "most effective light troops" while the British desperately needed the Indian tribes to compensate for their numerical inferiority.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} The Indians, regardless of which side they fought for, saw themselves as allies, not subordinates and Indian chiefs did what they viewed as best for their tribes, much to the annoyance of both American and British generals, who often complained about the "unreliability" of the Indians.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=25}} |

|||

==Declaration of war== |

|||

[[File:1812 War Declaration.jpg|thumb|upright|U.S. Declaration of War]] |

|||

[[File:Proclamation Province of Upper Canada by Isaac Brock.jpg|upright|thumb|Proclamation by [[Isaac Brock]] in response to the U.S. declaration of war]] |

|||

{{Wikisource|US Declaration of War against the United Kingdom}} |

{{Wikisource|US Declaration of War against the United Kingdom}} |

||

On June |

On 1 June 1812, Madison sent a message to Congress recounting American grievances against Great Britain, though not specifically calling for a declaration of war. The [[United States House of Representatives|House of Representatives]] then deliberated for four days behind closed doors before voting 79 to 49 (61%) in favour of [[United States declaration of war upon the United Kingdom|the first declaration of war]]. The [[United States Senate|Senate]] concurred in the declaration by a 19 to 13 (59%) vote in favour. The declaration focused mostly on maritime issues, especially involving British blockades, with two thirds of the indictment devoted to such impositions, initiated by Britain's Orders in Council.{{efn|Hickey|1989|p=44}} The conflict began formally on 18 June 1812, when Madison signed the measure into law. He proclaimed it the next day.{{sfn|Woodworth|1812}} This was the first time that the United States had formally [[Declaration of war by the United States#Formal|declared war]] on another nation, and the Congressional vote was approved by the smallest margin of any declaration of war in America's history.{{sfn|Summer 1812: Congress}}{{sfn|Clymer|1991}} None of the 39 [[Federalist]]s in Congress voted in favour of the war, while other critics referred to it as "Mr. Madison's War".{{sfn|Hickey|1989|p=1}}{{sfn|Summer 1812: Congress}} Just days after war had been declared, a small number of Federalists in [[Baltimore]] were attacked for printing anti-war views in a newspaper, which eventually led to over a month of deadly [[1812 Baltimore riots|rioting]] in the city.{{sfn|Gilje|1980|p=551}} |

||

Prime Minister [[Spencer Perceval]] was [[Assassination of Spencer Perceval|assassinated]] in London on 11 May and [[Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool|Lord Liverpool]] came to power. He wanted a more practical relationship with the United States. On June 23, he issued a repeal of the [[Order in Council|Orders in Council]], but the United States was unaware of this, as it took three weeks for the news to cross the Atlantic.{{sfn|Toll|2006|p=329}} On 28 June 1812, {{HMS|Colibri|1809|6}} was dispatched from Halifax to New York under a flag of truce. She anchored off [[Sandy Hook, New Jersey|Sandy Hook]] on July 9 and left three days later carrying a copy of the declaration of war, British ambassador to the United States [[Augustus Foster]] and consul Colonel [[Thomas Henry Barclay]]. She arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia eight days later. The news of the declaration took even longer to reach London.{{sfnm|Stanley|1983|1p=4|Clarke|1812|2p=73}} |

|||

British commander [[Isaac Brock]] in Upper Canada received the news much faster. He issued a proclamation alerting citizens to the state of war and urging all military personnel "to be vigilant in the discharge of their duty", so as to prevent communication with the enemy and to arrest anyone suspected of helping the Americans.{{sfn|Proclamation: Province of Upper Canada|1812}}{{sfn|Turner|2011|p=311}} He also ordered the British garrison of [[Fort St. Joseph (Ontario)|Fort St. Joseph]] on [[Lake Huron]] to capture the American fort at [[Fort Mackinac|Mackinac]]. This fort commanded the [[Straits of Mackinac|passage between Lakes Huron and Michigan]], which was important to the fur trade. The British garrison, aided by fur traders of the [[North West Company]] and Sioux, Menominee, Winnebago, Chippewa, and Ottawa, immediately [[Siege of Fort Mackinac|besieged and captured Mackinac]].<ref>Alec R. Gilpin, ''The War of 1812 in the Old Northwest'', Michigan State University Press, p. 89</ref> |

|||

==Course of |

== Course of war == |

||

{{ |

{{see also|Timeline of the War of 1812}} |

||

The war was conducted in several theatres: |

|||

# The [[Canada–United States border]]: the [[Great Lakes region]] ([[Old Northwest]] and [[Upper Canada]]), the [[Niagara Frontier]], and the [[St. Lawrence River]] ([[New England]] and [[Lower Canada]]). |

|||

# At sea, principally the Atlantic Ocean and the [[East Coast of the United States|American east coast]]. |

|||

# The [[Gulf Coast of the United States|Gulf Coast]] and Southern United States (including the [[Creek War]] in the [[Alabama River]] basin). |

|||

# The [[Mississippi River]] basin. |

|||

=== |

=== Unpreparedness === |

||

[[File:Anglo American War 1812 Locations map-en.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|Northern theatre, War of 1812]] |

|||

Although the outbreak of the war had been preceded by years of angry diplomatic dispute, neither side was ready for war when it came. Britain was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the [[British Army]] was deployed in the [[Peninsular War]] (in Portugal and Spain), and the Royal Navy was compelled to blockade most of the coast of Europe. The number of British regular troops present in Canada in July 1812 was officially stated to be 6,034, supported by Canadian militia.{{sfn|Hickey|1989|pp=72–75}} Throughout the war, the British [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]] was the [[Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst|Earl of Bathurst]]. For the first two years of the war, he could spare few troops to reinforce North America and urged the [[commander-in-chief]] in North America (Lieutenant General Sir [[George Prévost]]) to maintain a defensive strategy. The naturally cautious Prévost followed these instructions, concentrating on defending [[Lower Canada]] at the expense of Upper Canada (which was more vulnerable to American attacks) and allowing few offensive actions. |

|||

The war had been preceded by years of diplomatic dispute, yet neither side was ready for war when it came. Britain was heavily engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, most of the British Army was deployed in the Peninsular War in Portugal and Spain, and the Royal Navy was blockading most of the coast of Europe.{{sfn|Hannay|1911|p=847}} The number of British regular troops present in Canada in July 1812 was officially 6,034, supported by additional Canadian militia.{{sfn|Hickey|1989|pp=72–75}} Throughout the war, the British [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies|War Secretary]] was [[Henry Bathurst, 3rd Earl Bathurst|Earl Bathurst]], who had few troops to spare for reinforcing North America defences during the first two years of the war. He urged Lieutenant General [[George Prévost]] to maintain a defensive strategy. Prévost, who had the trust of the Canadians, followed these instructions and concentrated on defending Lower Canada at the expense of Upper Canada, which was more vulnerable to American attacks and allowed few offensive actions. Unlike campaigns along the east coast, Prevost had to operate with no support from the Royal Navy.{{sfnm|Hannay|1911|1pp=22–24|Hickey|1989|2p=194}} |

|||

[[File:Battle of Queenston Heights, Artist Unknown.jpg|thumb|The ''[[Battle of Queenston Heights]]'' depicts the unsuccessful American landing on 13 October 1812]] |

|||

The United States was not prepared to prosecute a war, for Madison had assumed that the state militias would easily seize Canada and that negotiations would follow. In 1812, the regular army consisted of fewer than 12,000 men. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men, but the service was voluntary and unpopular; it offered poor pay, and there were few trained and experienced officers, at least initially.{{sfn|Quimby|1997|pp=2–12}} The militia objected to serving outside their home states, were not open to discipline, and performed poorly against British forces when outside their home states. American prosecution of the war suffered from its unpopularity, especially in [[New England]], where anti-war speakers were vocal. "Two of the Massachusetts members [of Congress], [[Ebenezer Seaver|Seaver]] and [[William Widgery|Widgery]], were publicly insulted and hissed on Change in Boston; while another, [[Charles Turner, Jr.|Charles Turner]], member for the [[Plymouth, Massachusetts|Plymouth]] district, and Chief-Justice of the Court of Sessions for that county, was seized by a crowd on the evening of August 3, [1812] and kicked through the town".{{sfn|Adams|1918|p=400}} The United States had great difficulty financing its war. It had disbanded its [[First Bank of the United States|national bank]], and private bankers in the Northeast were opposed to the war. The United States was able to obtain financing from London-based [[Barings Bank]] to cover overseas bond obligations.<ref>{{cite news |last=Hickey |first=Donald R. |url=http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/138230/donald-r-hickey/small-war-big-consequences |title= Small War, Big Consequences: Why 1812 Still Matters |work=[[Foreign Affairs]] |publisher=[[Council on Foreign Relations]] |date=November 2012 |deadurl=no |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116043836/http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/138230/donald-r-hickey/small-war-big-consequences |archivedate=2013-01-16 |accessdate=2014-07-26}}</ref> The failure of New England to provide militia units or financial support was a serious blow.{{sfn|Hickey|1989|p=80}} Threats of secession by New England states were loud, as evidenced by the Hartford Convention. Britain exploited these divisions, blockading only southern ports for much of the war and encouraging smuggling.{{sfn|Heidler|Heidler|1997|pp=233–34, 349–50, 478–79}} |

|||

The United States was also not prepared for war.<ref>{{Cite web |title=War Of 1812 {{!}} Encyclopedia.com |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/united-states-and-canada/us-history/war-1812 |access-date=2023-07-18 |website=www.encyclopedia.com}}</ref> Madison had assumed that the state militias would easily seize Canada and that negotiations would follow. In 1812, the regular army consisted of fewer than 12,000 men. Congress authorized the expansion of the army to 35,000 men, but the service was voluntary and unpopular; it paid poorly and there were initially few trained and experienced officers.{{sfn|Quimby|1997|pp=2–12}} The militia objected to serving outside their home states, they were undisciplined and performed poorly against British forces when called upon to fight in unfamiliar territory.{{sfn|Hannay|1911|p=847}} Multiple militias refused orders to cross the border and fight on Canadian soil.{{sfn|Dauber|2003|p=301}} |

|||

===Upper Canada=== |

|||

On July 12, 1812, General [[William Hull]] led an invading American force of about 1,000 untrained, poorly equipped militia across the [[Detroit River]] and occupied the Canadian town of Sandwich (now a neighborhood of [[Windsor, Ontario]]).<ref>Steven J. Rauch, "A Stain upon the Nation? A Review of the Detroit Campaign of 1812 in United States Military History," ''Michigan Historical Review,'' 38 (Spring 2012), 129–153.</ref> Hull was not an aggressive leader and dithered, knowing that only one of his regiments were regular United States army troops while the other three were composed of ill-trained militiamen who Hull feared would not stand up to the test of combat.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=30}} The British Provincial Marine seized an American ship on Lake Erie carrying Hull's supplies, which led Hull to cross the slower overland route to bring up his supplies, which additionally had to face the prospect of being ambushed by Indians loyal to Tecumseh.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=30}} On 17 July, the British captured Mackinac island, which led Hull to assume that all of the Indians in the Old Northwest would rise up against the Americans.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=30-31}} On 8 August, Hull and his troops (numbering 2,500 with the addition of 500 [[Canadians]]) retreated to Detroit, where they surrendered to a significantly smaller force of British regulars, Canadian militia and Native Americans, led by British Major General [[Isaac Brock]] and [[Shawnee]] leader [[Tecumseh]].{{sfn|Heidler|Heidler|1997|p=248}} The surrender not only cost the United States the village of Detroit, but control over most of the [[Michigan Territory]]. By capturing Detroit, Brock had secured his western flank for the moment, gave his forces much needed equipment, as the Upper Canada militia was short of arms, and persuaded the waving population of Upper Canada that the British could hold out.{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=34}} The Iroquois living on the Grand River, who until had ignoring Brock's orders to report to his command, now sent 450 warriors out to join the British..{{sfn|Benn|2002|p=34}} Several months later, the U.S. launched a second invasion of Canada, this time at the [[Niagara Peninsula|Niagara peninsula]]. On October 13, United States forces were again defeated at the [[Battle of Queenston Heights]], where General Brock was killed.{{sfn|Heidler|Heidler|1997|pp=437–8}} |

|||