University of Pennsylvania: Difference between revisions

Shrugcover (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Private university in Philadelphia, US}} |

|||

{{about|the private Ivy League school in Philadelphia|the public research school in University Park|Pennsylvania State University}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2023}} |

|||

{{short description|Private research university in Philadelphia}} |

|||

{{About|the private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia|the public research university with campuses across Pennsylvania|Pennsylvania State University}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2018}} |

|||

{{multiple issues| |

|||

{{overly detailed|date=June 2024}}{{Academic booster|date=July 2023}}}} |

|||

{{Infobox university |

{{Infobox university |

||

| name = University of Pennsylvania |

| name = University of Pennsylvania |

||

| former_names = {{ubli|Academy and Charitable School in the Province of Pennsylvania (1751–1755) | College of Philadelphia (1755–1779, 1789–1791)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html |title=Penn in the 18th Century |website=upenn.edu |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060428155156/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html |archive-date=April 28, 2006 |access-date=July 20, 2021}}</ref>| University of the State of Pennsylvania (1779{{refn|group=note|It was not until 1785 that the name was made official as between 1779 and 1785 name was simply "University" in Philadelphia—see {{cite web |url=https://secretary.upenn.edu/trustees-governance/statutes-trustees |title=Statutes of the Trustees |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=September 12, 2022}}}}–1791) }} |

|||

| former_names = Academy and Charitable School in the Province of Pennsylvania <small>(1751–1755)</small><br/>College of Philadelphia <small>(1755–1779)</small><br/>University of the State of Pennsylvania <small>(1779–1791)</small> |

|||

| image = UPenn shield with banner.svg |

|||

| image_name = UPenn_shield_with_banner.svg |

|||

| image_upright = 0. |

| image_upright = 0.75 |

||

| image_alt = Arms of the University of Pennsylvania |

| image_alt = Arms of the University of Pennsylvania |

||

| caption = [[Coat of arms of the University of Pennsylvania|Coat of arms]] |

|||

| latin_name = Universitas Pennsylvaniensis |

|||

| latin_name = Universitas Pennsylvaniensis<ref>{{cite web | url=https://secretary.upenn.edu/trustees-governance/frequently-asked-questions | title=Frequently Asked Questions | Office of the University Secretary }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Record of the Jubilee Celebrations of the University of Sydney |date=1903 |publisher=William Brooks and Co. |isbn=9781112213304 |publication-place=[[Sydney]], [[New South Wales]] |language=en-AU }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Actes du Jubilé de 1909 |date=1910 |publisher=Georg Keck & Cie |isbn=9781360078335 |publication-place=[[Geneva]], [[Switzerland]] |language=fr-CH }}</ref> |

|||

| motto = {{lang|la|Leges sine moribus vanae}} (Latin) |

|||

| motto = {{lang|la|Leges sine moribus vanae}} ([[Latin language|Latin]]) |

|||

| mottoeng = Laws without morals are useless |

|||

| mottoeng = "Laws without morals are useless" |

|||

| established = {{start date and age|1740|11|14}}{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"|The University officially uses 1740 as its founding date and has since 1899. The ideas and intellectual inspiration for the academic institution stem from 1749, with a pamphlet published by [[Benjamin Franklin]] (1705/1706–1790). When Franklin's institution was established, it inhabited a schoolhouse built on November 14, 1740 for another school, which never came to practical fruition.<ref name="archives.upenn.edu">{{cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history|title=Penn History Exhibits - University Archives and Records Center|website=archives.upenn.edu|access-date=January 31, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190822113907/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history|archive-date=August 22, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> Penn archivist Mark Frazier Lloyd noted, "In 1899, UPenn's Trustees adopted a resolution that established 1740 as the founding date, but good cases may be made for 1749, when Franklin first convened the Trustees, or 1751, when the first classes were taught at the affiliated secondary school for boys, Academy of Philadelphia, or 1755, when Penn obtained its collegiate charter to add a post-secondary institution, the College of Philadelphia."<ref name="upenn.edu">{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110603231438/http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231|archive-date=2011-06-03|title=A Penn Trivial Pursuit - Penn Current|date=June 3, 2011}}</ref> Princeton's library presents another diplomatically-phrased view.<ref name="princeton.edu">{{cite web|url=http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030319132644/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml|archive-date=2003-03-19|title=Seeley G. Mudd Library : FAQ Princeton vs. University of Pennsylvania: Which is the Older Institution?|date=March 19, 2003}}</ref>}} |

|||

| established = {{start date and age|1740|11|14}}{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"|The university officially uses 1740 as its founding date and has since 1899. The ideas and intellectual inspiration for the academic institution stem from 1749, with a pamphlet published by [[Benjamin Franklin]] (1705/1706–1790). When Franklin's institution was established, it inhabited a schoolhouse built on November 14, 1740, for another school, which never came to practical fruition.<ref name="archives.upenn.edu">{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history |title=Penn History Exhibits |publisher=University Archives and Records Center |access-date=January 31, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190822113907/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history |archive-date=August 22, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Penn archivist Mark Frazier Lloyd noted, "In 1899, UPenn's Trustees adopted a resolution that established 1740 as the founding date, but good cases may be made for 1749, when Franklin first convened the Trustees, or 1751, when the first classes were taught at the affiliated secondary school for boys, Academy of Philadelphia, or 1755, when Penn obtained its collegiate charter to add a post-secondary institution, the College of Philadelphia."<ref name="upenn.edu">{{cite web |url=http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110603231438/http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231 |archive-date=June 3, 2011 |title=A Penn Trivial Pursuit – Penn Current |date=June 3, 2011}}</ref> Princeton's library presents another diplomatically-phrased view.<ref name="princeton.edu">{{cite web |url=http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030319132644/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml |archive-date=March 19, 2003 |title=Seeley G. Mudd Library: FAQ Princeton vs. University of Pennsylvania: Which is the Older Institution?|date=March 19, 2003}}</ref>}} |

|||

| type = [[Private university|Private]] [[Doctoral university|research]] university |

|||

| type = [[Private university|Private]] [[research university]] |

|||

| affiliations = [[Association of American Universities|AAU]]<br />[[Consortium on Financing Higher Education|COFHE]]<br />[[National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities|NAICU]]<br />[[568 Group]]<br />[[Universities Research Association|URA]] |

|||

| accreditation = [[Middle States Commission on Higher Education|MSCHE]] |

|||

| endowment = $14.65 billion (2019)<ref name = endowment>As of June 30, 2019. {{cite web |url=https://www.nacubo.org/-/media/Nacubo/Documents/EndowmentFiles/2019-Endowment-Market-Values--Final-Feb-10.ashx? |title=U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised) |publisher=National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA |access-date=April 24, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

| academic_affiliations = {{hlist |

|||

| budget = $3.5 billion (2020)<ref>{{cite web |title=Operating Budget |url=https://www.budget.upenn.edu:44303/Operating_Budget/ |website=Office of Budget and Management Analysis |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=January 19, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191112170732/https://www.budget.upenn.edu:44303/Operating_Budget/ |archive-date=November 12, 2019 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

|[[Association of American Universities|AAU]] |

|||

| founder = [[Benjamin Franklin]] |

|||

|[[Consortium on Financing Higher Education|COFHE]] |

|||

| president = [[Amy Gutmann]] |

|||

|[[National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities|NAICU]]|[[Quaker Consortium|QC]] |

|||

| provost = [[Wendell Pritchett]] |

|||

|[[Universities Research Association|URA]] |

|||

| head_label = Board Chairman |

|||

}} |

|||

| head = [[David L. Cohen]]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://secure.www.upenn.edu/secretary/trustees/TrusteeNameList.html|publisher=Office of the University Secretary, Penn|date=January 1, 2018|access-date=March 15, 2018|title=The Trustees|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171004140026/https://secure.www.upenn.edu/secretary/trustees/TrusteeNameList.html|archive-date=October 4, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| |

| endowment = $21.0 billion (2023)<ref name = endowment>As of June 30, 2023. {{cite report |url=https://investments.upenn.edu/about-us |title=About Us Penn Office of Investments |publisher=Penn Office of Investments |date=June 30, 2023 |access-date=October 17, 2023 |archive-date=October 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231019034827/https://investments.upenn.edu/about-us |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

| |

| budget = $4.4 billion (2024)<ref>{{cite web |title=Operating Budget |url=https://budget.upenn.edu/operating-budget/ |publisher=Office of Budget and Management Analysis, University of Pennsylvania |access-date=2023-12-10 |archive-date=October 9, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231009003416/https://budget.upenn.edu/operating-budget/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

| founder = [[Benjamin Franklin]] |

|||

| undergrad = 10,019 (Fall 2019)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| president = [[J. Larry Jameson]] (interim)<!--J. Larry Jameson has been chosen as interim president (https://www.thedp.com/article/2023/12/penn-larry-jameson-interim-president).--> |

|||

| postgrad = 12,413 (Fall 2019)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| provost = [[John L. Jackson Jr.]] |

|||

| city = [[Philadelphia]] |

|||

| academic_staff = 4,793 (2018)<ref name="Facts">{{cite web |title=Penn: Penn Facts |url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/facts |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=January 18, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191023185249/https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts |archive-date=October 23, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| state = [[Pennsylvania]] |

|||

| students = {{gaps|23,374}} (fall 2022)<ref name="CDS">{{cite web |title=Common Data Set 2022–2023 |url=https://ira.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/UPenn-Common-Data-Set-2022-23-Jul-2023.pdf |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=Sep 12, 2023 |archive-date=Aug 3, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230803133606/https://ira.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/UPenn-Common-Data-Set-2022-23-Jul-2023.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| country = United States |

|||

| total_staff = {{gaps|39,859}} (fall 2020; includes health system)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts |title=Facts |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=February 1, 2020 |archive-date=January 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200124040550/https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| campus = Urban, {{convert|1085|acre|km2}} total:<br /> {{convert|299|acre|km2}}, [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] campus; <br />{{convert|694|acre|km2}}, [[New Bolton Center]]; <br />{{convert|92|acre|km2}}, [[Morris Arboretum]] |

|||

| undergrad = 9,760 (fall 2022)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| athletics = [[NCAA Division I]] –<br /> [[Ivy League]]<br />[[Philadelphia Big 5]]<br />[[City 6]] |

|||

| postgrad = {{gaps|13,614}} (fall 2022)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| colors = [[Shades of red#Penn red|Penn Red]] and [[Shades of blue#Penn blue|Penn Blue]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/styleguide-logo-branding|title=Logo & Branding Standards|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=April 1, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190723185326/https://www.upenn.edu/about/styleguide-logo-branding|archive-date=July 23, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><br />{{color box|#990000}} {{color box|#011F5B}} |

|||

| city = [[Philadelphia]] |

|||

| nickname = [[Penn Quakers|Quakers]] |

|||

| state = Pennsylvania |

|||

| website = {{URL|upenn.edu}} |

|||

| country = United States |

|||

| logo = University of Pennsylvania wordmark.svg |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|39|57|01|N|75|11|41|W|region:US-PA_type:edu|display=title,inline}} |

|||

| logo_upright = .7 |

|||

| campus = Large city |

|||

| campus_size = {{ubli|{{convert|1085|acre|ha}} (total); | {{convert|299|acre|ha}}, [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] campus; | {{convert|694|acre|ha}}, [[New Bolton Center]]; | {{convert|92|acre|ha}}, [[Morris Arboretum]]}} |

|||

<!--| pushpin_map = USA -->}} |

|||

| free_label2 = Newspaper |

|||

| free2 = ''[[The Daily Pennsylvanian]]'' |

|||

| sporting_affiliations = {{hlist|[[NCAA Division I FCS]] – [[Ivy League]]|[[Philadelphia Big 5]]|[[City 6]]|[[Intercollegiate Rowing Association|IRA]]|[[Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges|EARC]]|[[Eastern Association of Women's Rowing Colleges|EAWRC]]}} |

|||

| colors = {{college color list|team=Penn Quakers}} <!-- same as athletics, inserted automatically --> |

|||

| nickname = [[Penn Quakers|Quakers]] |

|||

| mascot = The Quaker |

|||

| website = {{Official URL}} |

|||

| logo = University of Pennsylvania wordmark.svg |

|||

| logo_upright = .67 |

|||

| free_label = |

|||

| free = <!--| pushpin_map = USA --> |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- Join the discussion on the article's talk page regarding the lead. --> |

<!-- Join the discussion on the article's talk page regarding the lead. --> |

||

<!-- Please do not make large changes to the lead without discussing them on the article's talk page. --> |

<!-- Please do not make large changes to the lead without discussing them on the article's talk page. --> |

||

<!-- Please keep the lead encyclopedic and factual. Please do not selectively cherry pick rankings or attempt to turn this into brochure ware. --> |

<!-- Please keep the lead encyclopedic and factual. Please do not selectively cherry pick rankings or attempt to turn this into brochure ware. --> |

||

<!-- There are already too many images on this page. Please do not add any further without Talk page discussion. And other than the initial Ben Franklin image, there should be no images in the left margin. --> |

|||

The '''University of Pennsylvania''' (commonly known as '''Penn'''{{refn|group=note|The registered trademark as the primary substitute for using the University's full name; it is part of the university's official brand.<ref name="branding">{{multiref2|1={{cite web |title=Penn Brand Standards |url=https://branding.web-resources.upenn.edu/ |website=UPenn Web Resources |publisher=University of Pennsylvania}} {{Webarchive |date= April 18, 2022 |url= https://web.archive.org/web/20220418015150/https://branding.web-resources.upenn.edu/}}|2= {{citation |title=UPenn Brand Guidelines |date= September 2022 |url=https://upenn.app.box.com/s/ya73qe5vsor49tlgqvv5pz2uz8yx750x |publisher=University of Pennsylvania}} }}</ref>}} or '''UPenn'''{{refn|group=note|name="name_style"|From ''The Pennsylvania Gazette'': "The University's online style guide says that while Penn is the officially sanctioned term, UPenn is 'permissible{{nbsp}}... in situations where it may help to distinguish Penn from other universities within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania."<ref>{{cite news |last1=Yagoda |first1=Ben |title=Penn v. UPenn |url=https://thepenngazette.com/penn-v-upenn/ |work=The Pennsylvania Gazette |date=29 August 2017}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211104102013/https://thepenngazette.com/penn-v-upenn |date=November 4, 2021}}</ref> ''UPenn'' is an element used in the university's domain name.}}) is a [[Private university|private]] [[Ivy League]] [[research university]] in [[Philadelphia]], Pennsylvania, United States. It is one of nine [[colonial colleges]] and was chartered prior to the [[United States Declaration of Independence|U.S. Declaration of Independence]] when [[Benjamin Franklin]], the university's founder and first president, advocated for an educational institution that trained leaders in academia, commerce, and [[public service]]. Penn identifies as the [[List of oldest universities in continuous operation|fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States]], though this representation is challenged by other universities since Franklin first convened the board of trustees in 1749, arguably making it the fifth-oldest.{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"}} |

|||

The '''University of Pennsylvania''' ('''Penn''' or '''UPenn''') is a [[Private university|private]] [[Ivy League]] [[research university]] in [[Philadelphia]], [[Pennsylvania]]. The university claims a founding date of 1740{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"}} and is one of the nine [[colonial colleges]] chartered prior to the [[U.S. Declaration of Independence]]. [[Benjamin Franklin]], Penn's founder and first president, advocated an educational program that trained leaders in commerce, government, and [[public service]], similar to a modern [[Liberal arts education|liberal arts]] curriculum.<ref name="Penn's Heritage"/> |

|||

The university has four undergraduate schools and 12 graduate and professional schools. Schools enrolling undergraduates include the [[University of Pennsylvania College of Arts & Sciences|College of Arts and Sciences]], the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science|School of Engineering and Applied Science]], the [[Wharton School]], and the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing|School of Nursing]]. Among its graduate schools are its [[University of Pennsylvania Law School|law school]], whose first professor [[James Wilson (Founding Father)|James Wilson]] participated in writing the first draft of the [[Constitution of the United States|U.S. Constitution]], its [[Perelman School of Medicine|medical school]], which was the first medical school established in North America, and the Wharton School, the nation's first collegiate business school. |

|||

In 2023, Penn ranked third among U.S. universities in [[List of countries by research and development spending|research expenditures]], according to the [[National Science Foundation]].<ref name="NCSES" >{{cite web |url=https://ncses.nsf.gov/surveys/higher-education-research-development/2023#survey-info |title=Higher Education Research and Development: Fiscal Year 2023 |publisher=National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics |date=November 25, 2024 |access-date=November 26, 2024 }}</ref> Its [[financial endowment|endowment]] is {{USD|21 billion|long=no}}, making it the [[List of colleges and universities in the United States by endowment|sixth-wealthiest private academic institution in the nation]] as of 2023. The University of Pennsylvania's main campus is located in the [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] neighborhood of [[West Philadelphia]], and is centered around [[College Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|College Hall]]. Notable campus landmarks include [[Houston Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|Houston Hall]], the first modern [[Student activity center|student union]], and [[Franklin Field]], the nation's first dual-level [[college football]] stadium and the nation's longest-standing [[NCAA Division I]] college football stadium in continuous operation.<ref name="10 old"/> The university's athletics program, the [[Penn Quakers]], fields varsity teams in 33 sports as a member of NCAA Division I's Ivy League conference. |

|||

Penn is also home to the first "[[Student activity center|student union]]" building and organization ([[Houston Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|Houston Hall]], 1896), the first Catholic student club in North America ([[Newman Center]], 1893),<ref>John Whitney Evans, ''Making the Best of a Bad Job? Newman Chaplains between the Code and the Council'', U.S. Catholic Historian, Vol. 11, No. 1, Sulpicians and Seminaries, Prelates and Priests (Winter, 1993), pp. 35–50.</ref> the first double-decker college football stadium ([[Franklin Field]], 1924 when second deck was constructed),<ref name="University Archives">{{cite web|last=Tannenbaum|first=Seth S.|title=Undergraduate Student Governance at Penn, 1895–2006|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/studtorg/stugovt/housclub.html|work=University Archives and Research Center|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=August 19, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170423224237/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/studtorg/stugovt/housclub.html|archive-date=April 23, 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.upenn.edu/about/history|title=Penn's Heritage {{!}} University of Pennsylvania|website=www.upenn.edu|language=en|access-date=2020-04-29}}</ref> and [[Morris Arboretum]], the official arboretum of the [[Pennsylvania|Commonwealth of Pennsylvania]]. The first general-purpose electronic computer ([[ENIAC]]) was developed at Penn and formally dedicated in 1946. In 2019, the university had an endowment of $14.65 billion, the [[List of colleges and universities in the United States by endowment|sixth-largest endowment]] of all universities in the United States,<ref name="endowment" /> as well as a research budget of $1.02 billion.<ref name="Penn: Penn Facts" /> The university's athletics program, the [[Penn Quakers|Quakers]], fields varsity teams in 33 sports as a member of the [[NCAA Division I]] [[Ivy League]] conference. |

|||

Penn alumni, trustees, and faculty include eight [[Founding Fathers of the United States]] who signed the [[United States Declaration of Independence|Declaration of Independence]],<ref name="upenn1">{{Cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/search/|title=Search|website=University Archives and Records Center}}</ref><ref name="upenn2"/> seven who signed the [[United States Constitution]],<ref name="upenn2"/> 24 members of the [[Continental Congress]], three [[President of the United States|presidents of the United States]],{{refn|group=note|name="Harrison"}} 38 Nobel laureates, nine foreign [[Head of state|heads of state]], three [[United States Supreme Court]] justices, at least four Supreme Court justices of foreign nations,<ref>see list with citations in Notable People section</ref> 32 [[United States Senate|U.S. senators]], 163 members of the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]], 19 [[Cabinet of the United States|U.S. Cabinet Secretaries]], 46 [[Governor (United States)|governors]], 28 [[State supreme court|State Supreme Court]] justices, 36 living undergraduate billionaires (the largest number of any U.S. college or university),<ref name="quartz"/> and five [[Medal of Honor]] recipients.<ref name="MoH Recipients">{{cite web |last1=Ahern |first1=Joseph-James |last2=Hawley |first2=Scott W. |date=January 2011 |title=Congressional Medals of Honor, Recipients from the Civil War |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/medal-of-honor |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190123201154/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/medal-of-honor |archive-date=January 23, 2019 |access-date=October 9, 2020 |publisher=Penn Libraries, University of Pennsylvania |website= University Archives and Records Center }}</ref><ref name="na">{{cite web |title=Frederick C. Murphy, Our Facility's Namesake |url=https://www.archives.gov/boston/exhibits/murphy |website=archives.gov |date=August 15, 2016 |publisher=National Archives at Boston |access-date=October 14, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

As of 2018, distinguished alumni include three [[U.S. Supreme Court]] justices, 32 [[U.S. senators]], 46 [[Governor (United States)|U.S. governors]], 163 members of the [[U.S. House of Representatives]], eight signers of the Declaration of Independence, 12 signers of the [[U.S. Constitution]], 24 members of the [[Continental Congress]], 14 foreign heads of state, and two [[President of the United States|presidents of the United States]], including the incumbent, [[Donald Trump]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://money.cnn.com/2014/09/16/luxury/top-colleges-with-billionaire-undergraduates/|title=Top 20 Colleges with the most billionaire alumni|agency=[[CNN]]|department=[[CNNMoney]]|date=September 17, 2014|access-date=September 17, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140920023934/http://money.cnn.com/2014/09/16/luxury/top-colleges-with-billionaire-undergraduates|archive-date=September 20, 2014|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="UBS and Wealth-X">{{cite web|quote=According to annual studies (UBS and Wealth-X Billionaire Census) by [[UBS]] and Wealth-X, the University of Pennsylvania has produced the most billionaires in the world, as measured by the number of undergraduate degree holders. Four of the top five schools were [[Ivy League]] institutions.|url=http://www.wealthx.com/articles/2014/which-universities-produce-the-most-billionaires/|title=Which Universities Produce the Most Billionaires?|access-date=December 30, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141231010617/http://www.wealthx.com/articles/2014/which-universities-produce-the-most-billionaires/|archive-date=December 31, 2014|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/notables/signers.html|title=Penn Signers of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence|publisher=Archives.upenn.edu|access-date=January 24, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170307090215/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/notables/signers.html|archive-date=March 7, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> As of October 2019, [[List of Nobel laureates by university affiliation|36 Nobel laureates]], 80 members of the [[American Academy of Arts and Sciences]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|title=Facts | University of Pennsylvania|publisher=Upenn.edu|access-date=January 24, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191023185249/https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|archive-date=October 23, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> 64 [[billionaires]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/18/the-universities-that-produce-the-most-billionaires.html|title=More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT, and Yale combined|first1=Kathleen|last1=Elkins|publisher=CNBC|date=May 18, 2018|access-date=January 30, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180522013005/https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/18/the-universities-that-produce-the-most-billionaires.html|archive-date=May 22, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> 29 [[Rhodes Scholarship|Rhodes Scholars]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/rhodes|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|title=Rhodes Scholarships|access-date=December 7, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200127024829/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/rhodes|archive-date=January 27, 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> 15 [[Marshall Scholarship|Marshall Scholars]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/marshall-students|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|title=Marshall Scholarships|access-date=December 7, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200127024809/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/marshall-students|archive-date=January 27, 2020|url-status=live}}</ref> and 16 [[Pulitzer Prize]] winners have been affiliated with the university. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{Main|History of the University of Pennsylvania}} |

|||

[[File:Benjamin_Franklin_by_Joseph_Duplessis_1778.jpg|thumb|[[Benjamin Franklin]] was the primary founder, benefactor, President of the Board of Trustees and a trustee of the [[The Academy and College of Philadelphia|Academy and College of Philadelphia]], which merged with the [[University of the State of Pennsylvania]] to form the University of Pennsylvania in 1791 ([[Joseph Duplessis]], c. 1785).]] |

|||

In 1740, a group of [[Philadelphia]]ns organized to erect a great preaching hall for [[George Whitefield]], a traveling [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] [[evangelism|evangelist]],<ref>see second footnote 9 in Extracts from the Benjamin Franklin published Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230826064004/https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 |date=August 26, 2023 }} "Note: The annotations to this document, and any other modern editorial content, are copyright the American Philosophical Society and Yale University. All rights reserved."</ref> which was designed and constructed by [[Edmund Woolley]]. It was the largest building in Philadelphia at the time, and thousands of people attended it to hear Whitefield preach.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory">{{cite book|title=A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770|publisher=George W. Jacobs & Co.|author=Montgomery, Thomas Harrison|year=1900|location=Philadelphia|lccn=00003240|title-link=:File:History of the University of Pennsylvania - Montgomery (1900).djvu}}</ref>{{rp|26}} |

|||

[[File:PA-Philadelphia-Penn.jpg|thumb|Academy and College of Philadelphia (c. 1780), 4th and Arch Streets, Philadelphia, home of what became the University from 1751 to 1801]] |

|||

[[File:House intended for the President Birch's Views Plate 13.jpg|thumb|"House intended for the President of the United States" from "[[Birch's Views of Philadelphia]]" (1800), home of the College of Philadelphia/University of Pennsylvania from 1801 to 1829]] |

|||

[[File:University of Pennsylvania, Ninth Street, above Chesnut, by Bartlett & French 2.jpg|thumb|Ninth Street Campus (above Chestnut Street) in [[stereographic]] image: Medical Hall (left) and College Hall (right), both built 1829–1830]] |

|||

The University of Pennsylvania considers itself the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, though this is contested by Princeton and Columbia Universities.{{refn|group=note| Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution. The College of Philadelphia (later Penn), [[Princeton University|College of New Jersey (later Princeton University)]] and [[Columbia University|King's College (later Columbia College, now Columbia University)]] all originated within a few years of each other. After initially designating 1750 as its founding date, Penn later considered 1749 to be its founding date for more than a century, including alumni observing a centennial celebration in 1849. In 1895, several elite universities in the United States convened in New York City as the "Intercollegiate Commission" at the invitation of [[John James McCook (lawyer)|John J. McCook]], a [[Union Army]] officer during the [[American Civil War]] and member of Princeton's board of trustees who chaired its Committee on Academic Dress. The primary purpose of the conference was to standardize American academic regalia, which was accomplished through the adoption of the [[Academic regalia in the United States|Intercollegiate Code on Academic Costume]]. This formalized protocol included a provision that henceforth [[academic procession]]s would place visiting dignitaries and other officials in the order of their institution's founding dates. The following year, Penn's ''The Alumni Register'' magazine, published by the General Alumni Society, began a campaign to retroactively revise the University's founding date to 1740, to become older than Princeton, which had been chartered in 1746. Three years later in 1899, Penn's board of trustees acceded to this alumni initiative and officially changed its founding date from 1749 to 1740, affecting its rank in academic processions as well as the informal bragging rights that come with the age-based hierarchy in academia generally. See "Building Penn's Brand" for more details on why Penn did this.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0902/thomas.html|title=Gazette: Building Penn's Brand (Sept/Oct 2002)|website=www.upenn.edu|access-date=January 25, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051120020503/http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0902/thomas.html|archive-date=November 20, 2005|url-status=live}}</ref> Princeton implicitly challenges this rationale,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.princeton.edu/meet-princeton/history|title=History|website=Princeton University|access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190805225330/https://www.princeton.edu/meet-princeton/history|archive-date=August 5, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> also considering itself to be the nation's fourth-oldest institution of higher learning.<ref>[https://www.princeton.edu/main/about/history/american-revolution/] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160403053852/http://www.princeton.edu/main/about/history/american-revolution/ |date=April 3, 2016 }}</ref> To further complicate the comparison, a [[University of Edinburgh]]-educated [[Presbyterian]] minister from Scotland, named [[William Tennent]] and his son [[Gilbert Tennent]] operated a "[[Log College]]" in [[Bucks County, Pennsylvania]], from 1726 until 1746; some have suggested a connection between it and Princeton because five members of Princeton's first Board of Trustees were affiliated with the "Log College", including Gilbert Tennent, William Tennent, Jr., and Samuel Finley, the latter of whom later became President of Princeton. All twelve members of Princeton's first Board of Trustees were leaders from the "[[The Old Side-New Side Controversy|New Side]]" or "[[Old and New Light|New Light]]" wing of the [[Presbyterian Church]] in the [[New Jersey]], [[New York (state)|New York]] and [[Pennsylvania]] areas.<ref>[https://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/founders.shtml] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131105013448/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/founders.shtml |date=November 5, 2013 }}</ref> This antecedent relationship, when considered a formal lineage with institutional continuity, would justify pushing Princeton's founding date back to 1726, earlier than Penn's 1740. However, Princeton has not done so, and a Princeton historian says that "the facts do not warrant" such an interpretation.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://etcweb1.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/log_college.html|title=Archived copy|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051117052303/http://etcweb1.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/log_college.html|archive-date=November 17, 2005|url-status=dead|access-date=January 30, 2006}}</ref> Columbia also implicitly challenges Penn's use of either 1750, 1749 or 1740, as it claims to be the fifth oldest institution of higher learning in the United States (after Harvard, William & Mary, Yale and Princeton), based upon its charter date of 1754 and Penn's charter date of 1755.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.columbia.edu/content/history|title=History - Columbia University in the City of New York|website=www.columbia.edu|access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517175032/https://www.columbia.edu/content/history|archive-date=May 17, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> Academic histories of American higher education generally list Penn as fifth or sixth, after Princeton and immediately before or after that of Columbia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ConspectusH/id/345|title=COH-03-057_Page-45|website=dmr.bsu.edu|access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200122150848/https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ConspectusH/id/345|archive-date=January 22, 2020|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/9120/article_RI234246.pdf?sequence=5 |title=AMERICAN COLONIAL COLLEGES |website=scholarship.rice.edu |format=PDF |access-date=2019-05-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116181127/http://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/9120/article_RI234246.pdf?sequence=5 |archive-date=January 16, 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3878/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00140.pdf?sequence=1 |title=THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN COLLEGESAND THEIR LIBRARIES IN THESEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES |last=Zubatsky |first=David |date=2007 |website=/www.ideals.illinois.edu |format=PDF |access-date=2019-05-16 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141028044908/https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3878/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00140.pdf?sequence=1 |archive-date=October 28, 2014 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In the fall of 1749, [[Benjamin Franklin]], a [[Founding Fathers of the United States|Founding Father]] and [[polymath]] in Philadelphia, circulated a pamphlet, "[[commons:File:Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (UC) - Benjamin Franklin (1931 1749).djvu|Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania]]," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|title=A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives|first=Steven Morgan|last=Friedman|website=Archives.upenn.edu|access-date=December 9, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100102143449/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|archive-date=January 2, 2010|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

Even Penn's account of its early history agrees that the original secondary school (the Academy of Philadelphia) did not add an institution of higher learning (the College of Philadelphia) until 1755, but university officials continue to make it their practice to assert their fourth-oldest place in academic processions. Other American universities that began as a colonial-era, early version of secondary schools such as [[St. John's College (Annapolis/Santa Fe)|St. John's College]] (founded as "King William's School" in 1696) and the [[University of Delaware]] (founded as "the Free Academy" in 1743) choose to march based upon the date they became institutions of higher learning. Penn History Professor Edgar Potts Cheyney was a member of the Penn class of 1883 who played a leading role in the 1896-1899 alumni campaign to change the university's formal founding date. According to Cheyney's later history of the event, the university did indeed consider its founding date to be 1749 for almost a century. However, it was changed with good reason, and primarily due to a publication about the university issued by the [[United States Secretary of Education|U.S. Commissioner of Education]] written by Francis Newton Thorpe, a fellow alumnus, and colleague in the Penn history department. The year 1740 is the date of the establishment of the first educational trust that the University had taken upon itself. Cheyney states further that "it might be considered a lawyer's date; it is a familiar legal practice in considering the date of any institution to seek out the oldest trust it administers". He also points out that Harvard's founding date is also the year in which the [[Massachusetts General Court]] (state legislature) resolved to establish a fund in a year's time for a "School or College". As well, Princeton claims its founding date as 1746, the date of its first charter. However, the exact words of the charter are unknown, the number and names of the trustees in the charter are unknown, and no known original is extant. Except for Columbia University, the majority of the American Colonial Colleges do not have clear-cut dates of foundation <ref>Edgar Potts Cheyney, "History of the University of Pennsylvania: 1740-1940", Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940: pp. 45-52.</ref>}} The university also considers itself as the [[first university in the United States]] with both undergraduate and graduate studies. |

|||

On June 16, 1755, the [[Academy and College of Philadelphia|College of Philadelphia]] was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction.<ref name="WoodHistory">{{cite book|lccn=07007833|oclc=760190902|title=The History of the University of Pennsylvania, from Its Origin to the Year 1827|publisher= McCarty and Davis|last=Wood|first=George Bacon|author-link=George Bacon Wood|year=1834|title-link=:s:en:The History of the University of Pennsylvania|page=13}}</ref> |

|||

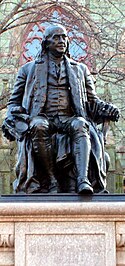

[[File:Benjamin Franklin statue in front of College Hall.JPG|thumb|right|This statue of [[Benjamin Franklin]] donated by Justus C. Strawbridge to the [[Philadelphia|City of Philadelphia]] in 1899 now sits in front of [[College Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|College Hall.]]<ref>{{Cite book|title=Ceremonies Attending the Unveiling of the Statue of Benjamin Franklin|url=https://archive.org/details/ceremoniesatten02stragoog|quote=justus c strawbridge.|access-date=November 24, 2007|last=Strawbridge|first=Justus C.|publisher=Allen, Lane & Scott|isbn=978-1-103-92435-6|year=1899}}</ref>]] |

|||

In 1740, a group of Philadelphians joined together to erect a great preaching hall for the traveling [[evangelism|evangelist]] [[George Whitefield]], who toured the American colonies delivering open-air sermons. The building was designed and built by [[Edmund Woolley]] and was the largest building in the city at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time it was preached in.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory">{{cite book|title=A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770|publisher=George W. Jacobs & Co.|author=Montgomery, Thomas Harrison|year=1900|location=Philadelphia|lccn=00003240|title-link=:File:History of the University of Pennsylvania - Montgomery (1900).djvu}}</ref>{{rp|26}} It was initially planned to serve as a [[charity school]] as well, but a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended. According to Franklin's autobiography, it was in 1743 when he first had the idea to establish an academy, "thinking the Rev. [[Richard Peters (priest)|Richard Peters]] a fit person to superintend such an institution". However, Peters declined a casual inquiry from Franklin and nothing further was done for another six years.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory"/>{{rp|30}} In the fall of 1749, now more eager to create a school to educate future generations, [[Benjamin Franklin]] circulated a pamphlet titled "[[commons:File:Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (UC) - Benjamin Franklin (1931 1749).djvu|Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania]]", his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|title=A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives|first=Steven Morgan|last=Friedman|publisher=Archives.upenn.edu|access-date=December 9, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100102143449/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|archive-date=January 2, 2010|url-status=dead}}</ref> Unlike the other [[colonial colleges]] that existed in 1749—[[Harvard]], [[College of William & Mary|William & Mary]], [[Yale]], and [[Princeton]]—Franklin's new school would not focus merely on education for the clergy. He advocated an innovative concept of higher education, one which would teach both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and doing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] priest [[William Smith (Episcopal priest)|William Smith]] (1727-1803), who became the first [[provost (education)|provost]], and other [[Board of Trustees|trustees]] strongly preferred the traditional curriculum.<ref name="Penn's Heritage">{{cite web|title=Penn's Heritage|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/history|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=May 8, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160422090345/http://www.upenn.edu/about/history|archive-date=April 22, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680-1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), pp. 30.</ref> |

|||

==Campus== |

|||

Franklin assembled a board of trustees from among the leading citizens of Philadelphia, the first such non-sectarian board in America. At the first meeting of the 24 members of the board of trustees on November 13, 1749, the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House (later renamed and famously known since 1776 as "[[Independence Hall (United States)|Independence Hall]]"), was offered without cost by [[James Logan (statesman)|James Logan]], its owner, the trustees realized that the building erected in 1740, which was still vacant, would be an even better site. The original sponsors of the dormant building still owed considerable construction debts and asked Franklin's group to assume their debts and, accordingly, their inactive trusts. On February 1, 1750, the new board took over the building and trusts of the old board. On August 13, 1751, the "Academy of Philadelphia", using the great hall at 4th and Arch Streets, took in its first secondary students. A charity school also was chartered on July 13, 1753,<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|12}} by the intentions of the original "New Building" donors, although it lasted only a few years. On June 16, 1755, the "[[College of Philadelphia]]" was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction.<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|13}} All three schools shared the same board of trustees and were considered to be part of the same institution.<ref name=autogenerated1/> The first commencement exercises were held on May 17, 1757.<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|14}} |

|||

[[File:37th and Spruce SEPTA station.jpg|thumb|Primary architecture firm of Penn's main campus, [[Cope and Stewardson]], were Penn Professors who designed this Quadrangle dormitory on [[Collegiate Gothic]] style. Image that was taken in 2007 includes a replica of a non operational 1920s trolley car (similar to version that used to run down Locust Street) and now forms part of an entrance to SEPTA's 37th Street subway station]] |

|||

Much of Penn's current architecture was designed by the [[Philadelphia]]-based architecture firm [[Cope and Stewardson]], whose owners were Philadelphia born and raised architects and professors at Penn who also designed [[Princeton University]] and a large part of [[Washington University in St. Louis]].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/walter-cope/ | title=Walter Cope | access-date=March 23, 2023 | archive-date=March 23, 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230323061145/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/walter-cope/ | url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/john-stewardson/ | title=John Stewardson | website=University Archives and Records Center | access-date=March 23, 2023 | archive-date=March 23, 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230323060904/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/john-stewardson/ | url-status=live |publisher=Penn Libraries, University of Pennsylvania}}</ref> They were known for having combined the [[Gothic architecture]] of the [[University of Oxford]] and [[University of Cambridge]] with the local landscape to establish the [[Gothic Revival architecture|Collegiate Gothic]] style.<ref>{{Philadelphia Architects and Buildings |ar=23024 |Cope & Stewardson (fl. 1885–1912)}}</ref> |

|||

Penn's main artery at center of [[University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District|Penn's Campus Historic District]] is Locust Walk, |

|||

a pedestrian only walkway first announced by Penn President, [[Harold Stassen]] in 1948.<ref> Stassen was quoted in Volume 47, no. 4 (December 1948) issue: [pages 13-15] of the ''Pennsylvania Gazette'' that Locust Walk would make Penn, “one of the most beautiful metropolitan campuses in the world. The plan will result in a campus that is both utilitarian and beautiful.” see https://archives.upenn.edu/digitized-resources/docs-pubs/institutional-planning/gazette-expansion-plans-revealed-1948/ retrieved December 5, 2024</ref> Work began in the summer of 1960, and was completed in in 1972.<ref>https://penntoday.upenn.edu/2015-10-22/record/record-locust-walk retrieved December 5, 2024</ref> |

|||

[[File:Penn campus 2.jpg|thumb|"The Quad" in the Fall, from Fisher-Hassenfeld College House, facing Ware College House]] |

|||

[[File:Locust Walk - UPenn (53589301557).jpg|thumb| Penn's main artery, Locust Walk, a pedestrian artery traversing six blocks from 40th Street to 35th Street in University City, in a photo taken on March 1, 2024]] |

|||

The institution of higher learning was known as the College of Philadelphia from 1755 to 1779. In 1779, not trusting then-provost the [[William Smith (Episcopalian priest)|Reverend William Smith]]'s [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|"Loyalist"]] tendencies, the revolutionary State Legislature created a [[University of the State of Pennsylvania]].<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite web|title=Penn in the 18th Century, University of Pennsylvania Archives|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html|publisher=Universdity of Pennsylvania|access-date=April 29, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060428155156/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html|archive-date=April 28, 2006|url-status=dead}}</ref> The result was a schism, with Smith continuing to operate an attenuated version of the College of Philadelphia. In 1791, the legislature issued a new charter, merging the two institutions into a new University of Pennsylvania with twelve men from each institution on the new board of trustees.<ref name=autogenerated1/> |

|||

The present core campus covers over {{convert|299|acre|ha}} in a contiguous area of West Philadelphia's University City section, and the older heart of the campus comprises the [[University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District]]. All of Penn's schools and most of its research institutes are located on this campus. The surrounding neighborhood includes several restaurants, bars, a large upscale grocery store, and a movie theater on the western edge of campus. Penn's core campus borders [[Drexel University]] and is a few blocks from the University City campus of [[Saint Joseph's University]], which absorbed [[University of the Sciences]] in Philadelphia in a merger, and [[The Restaurant School at Walnut Hill College]]. |

|||

[[Wistar Institute]], a cancer research center, is also located on campus. In 2014, a new seven-story glass and steel building was completed next to the institute's original brick edifice built in 1897 further expanding collaboration between the university and the Wistar Institute.<ref>{{cite news|last=Clarke|first=Dominique|title=Wistar strategic plan includes new building and research|url=http://thedp.com/index.php/article/2011/09/wistar_strategic_plan_includes_new_building_and_research|access-date=November 10, 2011 |newspaper=The Daily Pennsylvanian|date=September 26, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120121203226/http://thedp.com/index.php/article/2011/09/wistar_strategic_plan_includes_new_building_and_research |archive-date=January 21, 2012|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Penn has three claims to being the first university in the United States, according to university archives director Mark Frazier Lloyd: the 1765 founding of the first medical school in America<ref name=WDL1>{{cite web|title=University of Pennsylvania|url=http://www.wdl.org/en/item/9432|publisher=[[World Digital Library]]|access-date=February 14, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101150332/http://www.wdl.org/en/item/9432/|archive-date=January 1, 2014|url-status=live}}</ref> made Penn the first institution to offer both "undergraduate" and professional education; the 1779 charter made it the first American institution of higher learning to take the name of "University"; and existing colleges were established as seminaries (although, as detailed earlier, Penn adopted a traditional seminary curriculum as well).<ref name="first university">{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/firstuniv.html|title=The University of Pennsylvania: America's First University|publisher=University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania|access-date=April 29, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060711051514/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/firstuniv.html|archive-date=July 11, 2006|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

The Module 6 Utility Plant and Garage at Penn was designed by BLT Architects and completed in 1995. Module 6 is located at 38th and Walnut and includes spaces for 627 vehicles, {{convert|9000|sqft|m2|abbr=on}} of storefront retail operations, a 9,500-ton chiller module and corresponding extension of the campus chilled water loop, and a 4,000-ton ice storage facility.<ref>{{cite web|title=University of Pennsylvania Module 6 Utility Plant and Garage|url=http://www.blta.com/#/3/0/4/7/|publisher=BLT Architects|access-date=August 19, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110812175412/http://blta.com/#/3/0/4/7/|archive-date=August 12, 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

After being located in downtown Philadelphia for more than a century, the campus was moved across the [[Schuylkill River]] to property purchased from the [[Blockley Almshouse]] in [[West Philadelphia]] in 1872, where it has since remained in an area now known as [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]]. Although Penn began operating as an academy or secondary school in 1751 and obtained its collegiate charter in 1755, it initially designated 1750 as its founding date; this is the year that appears on the first iteration of the university seal. Sometime later in its early history, Penn began to consider 1749 as its founding date and this year was referenced for over a century, including at the centennial celebration in 1849.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/trustees.html|title=Penn Trustees 1749-1800|publisher=University of Pennsylvania University Archives|access-date=July 23, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121125023024/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/trustees.html|archive-date=November 25, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 1899, the board of trustees voted to adjust the founding date earlier again, this time to 1740, the date of "the creation of the earliest of the many educational trusts the University has taken upon itself".<ref>{{cite book|title=History of the University of Pennsylvania 1740–1940|last=Cheyney|first=Edward Potts|author-link=Edward Potts Cheyney|year=1940|publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press|location=Philadelphia|pages=46–48|url=http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_history/5/|access-date=August 19, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110524003401/http://repository.upenn.edu/penn_history/5/|archive-date=May 24, 2011|url-status=live}} Cheyney was a Penn professor and alumnus from the class of 1883 who advocated the change in Penn's founding date in 1899 to appear older than both Princeton and Columbia. The explanation, "It will have been noted that 1740 is the date of the creation of the earliest of the many educational trusts the University has taken upon itself," is Professor Cheyney's justification (pp. 47-48) for Penn retroactively changing its founding date, not language used by the Board of Trustees.</ref> The board of trustees voted in response to a three-year campaign by Penn's General Alumni Society to retroactively revise the university's founding date to appear older than Princeton University, which had been chartered in 1746.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/notables/alumpres.html|title=Presidents of Penn Alumni|website=www.archives.upenn.edu|access-date=August 24, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160719203832/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/people/notables/alumpres.html|archive-date=July 19, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

In 2010, in its first significant expansion across the [[Schuylkill River]], Penn purchased {{convert|23|acre}} at the northwest corner of 34th Street and Grays Ferry Avenue, the then site of [[DuPont]]'s Marshall Research Labs. In October 2016, with help from architects [[Matthias Hollwich]], [[Marc Kushner]], and [[KSS Architects]], Penn completed the design and renovation of the center piece of the project, a former paint factory named ''Pennovation Works'', which houses shared desks, wet labs, common areas, a pitch bleacher, and other attributes of a tech incubator. The rest of the site, known as South Bank, is a mixture of lightly refurbished industrial buildings that serve as affordable and flexible workspaces and land for future development. Penn hopes that "South Bank will provide a place for academics, researchers, and entrepreneurs to establish their businesses in close proximity to each other to facilitate cross-pollination of their ideas, creativity, and innovation," according to a March 2017 university statement.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pennovation.upenn.edu/news/tracking-evolution-industry-34th-and-grays-ferry |title=Tracking The Evolution Of Industry At 34th And Grays Ferry |last=Helmer |first=Madeleine |date=March 16, 2017 |publisher=Pennovation Works University of Pennsylvania |access-date=March 19, 2021 |archive-date=June 23, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210623194534/https://www.pennovation.upenn.edu/news/tracking-evolution-industry-34th-and-grays-ferry |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===Early campuses=== |

|||

The Academy of Philadelphia, a secondary school for boys, began operations in 1751 in an unused church building at 4th and Arch Streets which had sat unfinished and dormant for over a decade. Upon receiving a collegiate charter in 1755, the first classes for the College of Philadelphia were taught in the same building, in many cases to the same boys who had already graduated from The Academy of Philadelphia. In 1801, the university moved to the unused Presidential Mansion at 9th and Market Streets, a building that both George Washington and John Adams had declined to occupy while Philadelphia was the temporary national capital.<ref name="WoodHistory">{{cite book|lccn=07007833|oclc=760190902|title=The History of the University of Pennsylvania, from Its Origin to the Year 1827|publisher= McCarty and Davis|author=Wood, George Bacon|author-link=George Bacon Wood|year=1834|title-link=:s:en:The History of the University of Pennsylvania}}</ref> Classes were held in the mansion until 1829 when it was demolished. Architect [[William Strickland (architect)|William Strickland]] designed twin buildings on the same site, College Hall and Medical Hall (both 1829–1830), which formed the core of the Ninth Street Campus until Penn's move to West Philadelphia in the 1870s. |

|||

=== |

===Parks and arboreta=== |

||

{{Further|Morris Arboretum}} |

|||

[[File:U Penn Statue.jpg|thumb|Statue of the Reverend George Whitefield at the University of Pennsylvania]] |

|||

In 2007, Penn acquired about {{convert|35|acre|ha}} between the campus and the [[Schuylkill River]] at the former site of the [[Philadelphia Convention Hall and Civic Center|Philadelphia Civic Center]] and a nearby {{convert|24|acre|ha|adj=on}} site then owned by the [[United States Postal Service]]. Dubbed the Postal Lands, the site extends from [[Market Street (Philadelphia)|Market Street]] on the north to Penn's Bower Field on the south, including the former main regional U.S. Postal Building at 30th and Market Streets, now the regional office for the [[United States Internal Revenue Service|U.S. Internal Revenue Service]]. Over the next decade, the site became the home to educational, research, [[biomedical engineering|biomedical]], and [[Mixed-use development|mixed-use]] facilities. The first phase, comprising a park and athletic facilities, opened in the fall of 2011. |

|||

From its founding until construction of the [[Quadrangle Dormitories (University of Pennsylvania)|Quadrangle Dormitories]], which started construction in 1895, the student body did not live in university-owned housing as, with minor exceptions, there was none. Indeed a significant portion of the undergraduate population commuted from [[Delaware Valley]] and a large number of students resided in the Philadelphia area.<ref>{{cite book |last=Baltzell |first=Digby |date=1996 |title=Puritan Boston and Quaker Philadelphia |location=Piscataway, NJ |publisher=Transaction Publishers |page=253 |isbn=978-1560008309}}</ref> The medical school (with roughly half the students) was a significant exception to this trend as it attracted a more geographically diverse population of students. For example, as of the mid-1850s, over half of the population of the medical school was from the southern part of the United States.<ref name="auto">{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/pa-album/quad |title=The Quadrangle |last=Linck |first=Elizabeth |date=1990 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190219015644/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/pa-album/quad |archive-date=February 19, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/civil-war.pdf |title=National Crisis, Institutional Change: Penn and the Civil War |last=Pieczynski |first=Denise |date=1990 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190302024615/https://archives.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/civil-war.pdf |archive-date=March 2, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In September 2011, Penn completed the construction of the {{USD|46.5 million|long=no}}, {{convert|24|acre|ha|adj=on}} Penn Park, which features passive and active recreation and athletic components framed and subdivided by canopy trees, lawns, and meadows. It is located east of the Highline Green and stretches from [[Walnut Street (Philadelphia)|Walnut]] to [[South Street (Philadelphia)|South Street]]s. |

|||

By 1931, first-year students were required to live in the quadrangle unless they received official permission to live with their families or other relatives.<ref name="auto"/> However, throughout this period and into the early post-World War II period, the university continued to have a large commuting population.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/pa-album/modern |title=The Modern Urban University |last=Bessin |first=James |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190302024747/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/pa-album/modern |archive-date=March 2, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> As an example, into the late 1940s, two-thirds of Penn women students were commuters.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Puckett|first1= John |last2=Lloyd|first2= Mark |date=1995 |title=Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950-2000 |location=Philadelphia, PA |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |page=45 |isbn=978-0812246803}}</ref> |

|||

Penn maintains two arboreta. The first, the roughly {{convert|300|acre|sp=us|adj=on}} Penn Campus Arboretum at the University of Pennsylvania, encompasses the entire [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] main campus. The campus arboretum is an urban forest with over 6,500 trees representing 240 species of trees and shrubs, ten specialty gardens and five urban parks,<ref name="arbnet">{{cite web |url=http://www.arbnet.org/morton-register/penn-campus-arboretum-university-pennsylvania-0 |title=Penn Campus Arboretum at the University of Pennsylvania |website=arbnet.org |access-date=March 19, 2021 |archive-date=April 19, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210419031738/http://www.arbnet.org/morton-register/penn-campus-arboretum-university-pennsylvania-0 |url-status=live }}</ref> which has been designated as a Tree Campus USA<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.arborday.org/programs/tree-campus-higher-education/|title=Tree Campus Higher Education at arborday.org|website=arborday.org|access-date=December 19, 2023|archive-date=December 2, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231202212455/https://www.arborday.org/programs/tree-campus-higher-education/|url-status=live}}</ref> since 2009 and formally recognized as an accredited ArbNet Arboretum since 2017.<ref name="arbnet"/> Penn maintains an interactive website linked to Penn's comprehensive tree inventory, which allows users to explore Penn's entire collection of trees.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.facilities.upenn.edu/ |title=Welcome |work=University of Pennsylvania Facilities & Real Estate |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=March 19, 2021 |archive-date=March 4, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210304222559/https://www.facilities.upenn.edu/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The second arboretum, [[Morris Arboretum]], which serves as the official arboretum of the [[Pennsylvania|Commonwealth of Pennsylvania]], is 92 acres and includes over 13,000 labelled plants from over 2,500 types, representing the temperate floras of [[North America]], [[Asia]], and [[Europe]], with a primary focus on Asia. |

|||

After World War II, Penn began a capital spending program to overhaul its campus, especially student housing. A large number of students migrating to universities under the GI Bill, and the resultant increase in Penn's student population, highlighted that Penn had outgrown previous expansions, which ended during the Depression-era. Nonetheless, in addition to a significant student population from the Delaware Valley, Penn attracted international students and students from most of the 50 states as early as the 1960s.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/media/2017/04/integrated-development-plan-1962.pdf#page=13 |title=Integrated Development Plan |date=1962 |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190302024635/https://archives.upenn.edu/media/2017/04/integrated-development-plan-1962.pdf#page=13 |archive-date=March 2, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> Referring to the developments of this time period, Penn Trustee Paul Miller remarked, "[t]he bricks-and-mortar Capital Campaign of the Sixties...built the facilities that turned Penn from a commuter school to a residential one...."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/digitized-resources/docs-pubs/institutional-planning/almanac-franklins-promise-1989|title="'Keeping Franklin's Promise' is the Billion-Dollar Goal," The Almanac, 1989|website=University Archives and Records Center, University of Pennsylvania|access-date=March 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190218082006/https://archives.upenn.edu/digitized-resources/docs-pubs/institutional-planning/almanac-franklins-promise-1989|archive-date=February 18, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> By 1961, 79% of male undergraduates and 57% of female undergraduates lived on campus.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/media/2017/04/integrated-development-plan-1962.pdf#page=67 |title=Integrated Development Plan |date=1962 |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190302024635/https://archives.upenn.edu/media/2017/04/integrated-development-plan-1962.pdf#page=67 |archive-date=March 2, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{cite web| url = https://gis.penndot.gov/CRGISAttachments/SiteResource/H001351_04H.pdf| title = National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Compton and Bloomfield| access-date = 2023-09-01| author = George E. Thomas| date = August 1978| archive-date = August 14, 2022| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220814120207/https://gis.penndot.gov/CRGISAttachments/SiteResource/H001351_04H.pdf| url-status = live}}</ref> |

|||

===New Bolton Center=== |

|||

From 1930 to 1966, there were 54 documented [[Rowbottom (riot)|Rowbottom riots]], a student tradition of rioting which included everything from car smashing to panty raids.<ref name=Rowbottom>{{cite web|last=McConaghy|first=Mary D.|title=Student Traditions Rowbottom: Documented Rowbottoms, 1910–1970|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/traditions/rowbottom/list.html|work=University Archives and Records Center|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=August 25, 2011|author2=Ashish Shrestha|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210233901/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/traditions/rowbottom/list.html|archive-date=February 10, 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> After 1966, there were five more instances of "Rowbottoms", the latest occurring in 1980.<ref name=Rowbottom /> |

|||

{{main|New Bolton Center}} |

|||

Penn also owns the {{convert|687|acre|ha|adj=on}} [[New Bolton Center]], the research and large-animal health care center of its veterinary school.<ref name="arch">{{cite web| url = https://www.dot7.state.pa.us/ce/SelectWelcome.asp| title = National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania| publisher = CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System| format = Searchable database| access-date = March 25, 2021| archive-date = July 21, 2007| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070721014609/https://www.dot7.state.pa.us/ce/SelectWelcome.asp| url-status = dead}} ''Note:'' This includes {{cite web| url = https://www.dot7.state.pa.us/ce_imagery/phmc_scans/H096882_01H.pdf| title = Pennsylvania Historic Resource Survey Form: South Brook Farm| access-date = December 16, 2012| author = George E. Thomas| date = June 1991| archive-date = December 16, 2013| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131216182522/https://www.dot7.state.pa.us/ce_imagery/phmc_scans/H096882_01H.pdf| url-status = dead}}</ref> Located near [[Kennett Square, Pennsylvania|Kennett Square]], New Bolton Center received nationwide media attention when [[Kentucky Derby]] winner [[Barbaro (horse)|Barbaro]] underwent surgery at its Widener Hospital for injuries suffered while running in the [[Preakness Stakes]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/barbaro/|title=Barbaro|access-date=December 19, 2023|archive-date=April 4, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230404200850/https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/barbaro/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Libraries===<!-- This section is linked from [[NeXT]] --> |

|||

In 1965, Penn students learned that the university was sponsoring research projects for the United States' [[United States biological weapons program|chemical and biological weapons program]].<ref name="CB Controversy">{{cite journal|last=Herman|first=Edward S.|author2=Robert J. Rutman |author3=University of Pennsylvania |title=University of Pennsylvania's CB Warfare Controversy|journal=BioScience|date=August 1967|volume=17|issue=8|pages=526–529|jstor=1294007|doi=10.2307/1294007}}</ref> According to [[Edward S. Herman|Herman]] and Rutman, the revelation that "CB Projects Spicerack and Summit were directly connected with U.S. military activities in Southeast Asia", caused students to petition Penn president [[Gaylord Harnwell]] to halt the program, citing the project as being "immoral, inhuman, illegal, and unbefitting of an academic institution".<ref name="CB Controversy" /> Members of the faculty believed that an academic university should not be performing classified research and voted to re-examine the University agency which was responsible for the project on November 4, 1965.<ref name="CB Controversy"/> |

|||

{{Further|Van Pelt Library}} |

|||

[[File:Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center - IMG 6589.JPG|thumb|[[Van Pelt Library]], Penn's main library building]] |

|||

[[File:Furness library.jpg|thumb|Penn's first standalone library, built in 1891 and designed by [[Frank Furness]], {{Circa|1915}}]] |

|||

[[File:Furness Lib interior looking N UPenn.JPG|thumb|The interior of the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Design|School of Design]]'s library]] |

|||

Penn library system has grown into a system of 14 libraries with 400 [[full-time equivalent]] (FTE) employees and a total operating budget of more than {{USD|48 million|long=no}}.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.library.upenn.edu/about/access/visitors |title=Penn Libraries Visitor Information |newspaper=Penn Libraries |access-date=March 14, 2022 |archive-date=March 14, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220314193318/https://www.library.upenn.edu/about/access/visitors |url-status=live }}</ref> The library system has 6.19 million book and serial volumes as well as 4.23 million [[microform]] items and 1.11 million e-books.<ref name="Facts"/> It subscribes to over 68,000 print serials and e-journals.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://datafarm.library.upenn.edu/|title=Penn Library Data Farm|access-date=December 24, 2009|archive-date=March 17, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110317083950/http://datafarm.library.upenn.edu/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{citation |title= Data Farm|url =http://datafarm.library.upenn.edu/ |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110317083950/http://datafarm.library.upenn.edu/|archive-date=March 17, 2011|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

In 1983, members of the [[Animal Liberation Front]] broke into the Head Injury Clinical Research Laboratory in the School of Medicine and stole research audio and video tapes. The stolen tapes were given to [[People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals|PETA]] who edited the footage to create a film, ''[[Unnecessary Fuss]]''. As a result of media coverage and pressure from [[animal rights activism|animal rights activists]], the project was closed down.<ref name="Ethics Report">{{Cite web|url=https://www.onlineethics.org/cms/17252.aspx|title=OEC - Reflections on the Organizational Locus of the Office for Protection from Research Risks (Research Involving Human Participants V2)|website=onlineethics.org|first=Charles R|last=McCarthy|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100806205817/https://www.onlineethics.org/cms/17252.aspx|archive-date=August 6, 2010|publisher=[[National Academy of Sciences]]|quote=The university was put on probation by OPRR. The Head Injury Clinic was closed. The chief veterinarian was fired, the administration of animal facilities was consolidated, new training programs for investigators and staff were initiated, and quarterly progress reports to OPRR were required.}}</ref> |

|||

The university has 15 libraries. [[Van Pelt Library]] on the Penn campus is the university's main library. The other 14 are: |

|||

The school gained notoriety in 1993 for the [[water buffalo incident]] in which a student who told a group of black students to "shut up, you water buffalo" was charged with violating the university's racial harassment policy.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://partners.nytimes.com/books/first/k/kors-university.html|author1=Alan Charles Kors|author2=Harvey A. Silverglate|title=The Shadow University|work=The New York Times|access-date=August 17, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090709085033/http://partners.nytimes.com/books/first/k/kors-university.html|archive-date=July 9, 2009|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

*The [[Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania|Annenberg School for Communication]] library located on [[Walnut Street (Philadelphia)|Walnut Street]] between 36th and 37th Streets |

|||

*The Archaeology and Anthropology Library located at the [[University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology|Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology]] |

|||

*The Biddle Law Library located on campus on the 3500 block of Sansom Street at the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Law|School of Law]] |

|||

*The Chemistry Library located on campus on 3300 block of Spruce Street in the Chemistry Building |

|||

*The Dental Medicine Library on campus on the 4000 the block of [[Locust Street]] at the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine|Dental School]] |

|||

*The [[Fisher Fine Arts Library]] located on campus on the 3400 block of Woodland Avenue |

|||

*The Holman Biotech Commons library located on campus on the 3500 block of Hamilton Walk adjacent to the Robert Wood Johnson Pavilion at the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine|Medical School]] and the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing|Nursing School]] |

|||

*The Humanities and Social Sciences Library, including [[Weigle Information Commons]], located on campus between 34th and 35th streets on Locust Street in the Van Pelt Library |

|||