Ad hominem: Difference between revisions

Note: Arguments from authority in themselves is never valid, as an argument's validity rests 100% on the argument itself (and not on the expositor's authority). Please refer to Richard Feynman's "What is science?" for elaboration. Tag: Reverted |

Undid revision 1265982755 by Madhu Gopal (talk) Not required in the lead. |

||

| (190 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Attacking the person rather than the argument}} |

|||

{{Self reference|"Personal attack" redirects here. For the Wikipedia policy, see [[Wikipedia:No personal attacks]].}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Personal attack|the Wikipedia policy|Wikipedia:No personal attacks|selfref=yes}} |

|||

{{short description|Argumentative strategies, usually fallacious}} |

|||

{{ |

{{title language|la}} |

||

{{ |

{{Good article}} |

||

'''''Ad hominem''''' ({{langnf||Latin|to the person}}), short for '''''argumentum ad hominem''''', refers to several types of arguments, most of which are [[Fallacy#Informal fallacy|fallacious]]. Typically this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other attribute of the person making an argument rather than attacking the substance of the argument itself. This avoids genuine debate by creating a diversion to some irrelevant but often highly charged issue. The most common form of this fallacy is "A makes a claim ''x'', B asserts that A holds a property that is unwelcome, and hence B concludes that argument ''x'' is wrong". |

|||

{{Langnf|la|'''Ad hominem'''|to the person}}, short for '''{{lang|la|argumentum ad hominem}}''', refers to several types of arguments that are usually [[Fallacy#Informal fallacy|fallacious]]. Often currently this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other attribute of the person making an argument rather than the substance of the argument itself. This avoids genuine debate by creating a diversion often using a totally irrelevant, but often highly charged attribute of the opponent's character or background. The most common form of this fallacy is "A" makes a claim of "fact", to which "B" asserts that "A" has a personal trait, quality or physical attribute that is repugnant thereby going off-topic, and hence "B" concludes that "A" has their "fact" wrong{{snd}}without ever addressing the point of the debate. Many contemporary politicians routinely use {{lang|la|ad hominem}} attacks, some of which can be encapsulated to a derogatory nickname for a political opponent used instead of political argumentation. (But modern democracy requires that voters make character judgements of representatives, so opponents may reasonably criticize their character and motives.) |

|||

The valid types of ad hominem arguments are generally only encountered in specialized philosophical usage. These typically refer to the dialectical strategy of using the target's own beliefs and arguments against them, while not agreeing with the validity of those beliefs and arguments. ''Ad hominem'' arguments were first studied in [[ancient Greece]]. [[John Locke]] revived the examination of ''ad hominem'' arguments in the 17th century. |

|||

Other uses of the term {{lang|la|ad hominem}} are more traditional, referring to arguments tailored to fit a particular audience, and may be encountered in specialized philosophical usage. These typically refer to the dialectical strategy of using the target's own beliefs and arguments against them, while not agreeing with the validity of those beliefs and arguments. {{lang|la|Ad hominem}} arguments were first studied in [[ancient Greece]]; [[John Locke]] revived the examination of {{lang|la|ad hominem}} arguments in the 17th century. |

|||

== History == |

|||

A common misconception is that an {{lang|la|ad hominem}} attack is synonymous with an [[insult]]. This is not true, although some {{lang|la|ad hominem}} arguments may be insulting by the person receiving the argument. |

|||

== History == |

|||

<!--Ancient history--> |

<!--Ancient history--> |

||

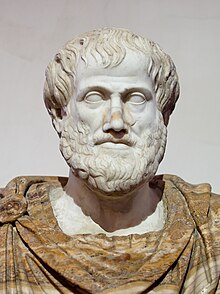

[[File:Aristotle Altemps Inv8575.jpg|thumb|Aristotle (384–322 |

[[File:Aristotle Altemps Inv8575.jpg|thumb|[[Aristotle]] (384–322 BC) is credited with raising the distinction between personal and logical arguments. |

||

The various types of ''ad hominem'' arguments have been known in the West since at least the ancient Greeks. [[Aristotle]], in his work ''[[Sophistical Refutations]]'', detailed the fallaciousness of putting the questioner but not the argument under scrutiny.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|p=82}} Many examples of ancient non-fallacious ''ad hominem'' arguments are preserved in the works of the [[Pyrrhonism|Pyrrhonist]] philosopher [[Sextus Empiricus]]. In these arguments, the concepts and assumptions of the opponents are used as part of a dialectical strategy against the opponents to demonstrate the unsoundness of their own arguments and assumptions. In this way, the arguments are to the person (''ad hominem''), but without attacking the properties of the individuals making the arguments.{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=2001|1p=207–209|2a1=Wong|2y=2017|2p=49}} |

|||

{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=2001|1p=208|2a1=Tindale|2y=2007|2p=82}}]] |

|||

<!--Modern era--> |

|||

Italian polymath [[Galileo Galilei]] and British philosopher [[John Locke]] also examined the argument from commitment, a form of the ''ad hominem'' argument, meaning examining an argument on the basis of whether it stands true to the principles of the person carrying the argument. In the mid-19th century, the modern understanding of the term ''ad hominem'' started to take shape, with the broad definition given by English logician [[Richard Whately]]. According to Whately, ''ad hominem'' arguments were "addressed to the peculiar circumstances, character, avowed opinions, or past conduct of the individual".{{sfn|Walton|2001|pp=208–210}} |

|||

The various types of {{lang|la|ad hominem}} arguments have been known in the West since at least the ancient Greeks. [[Aristotle]], in his work ''[[Sophistical Refutations]]'', detailed the fallaciousness of putting the questioner but not the argument under scrutiny.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|p=82}} His description was somewhat different from the modern understanding, referring to a class of [[sophistry]] that applies an ambiguously worded question about people to a specific person. The proper refutation, he wrote, is not to debate the attributes of the person ({{lang|la|solutio ad hominem}}) but to address the original ambiguity.{{sfn|Nuchelmans|1993|p=43}} Many examples of ancient non-fallacious {{lang|la|ad hominem}} arguments are preserved in the works of the [[Pyrrhonism|Pyrrhonist]] philosopher [[Sextus Empiricus]]. In these arguments, the concepts and assumptions of the opponents are used as part of a dialectical strategy against them to demonstrate the unsoundness of their own arguments and assumptions. In this way, the arguments are to the person ({{lang|la|ad hominem}}), but without attacking the properties of the individuals making the arguments.{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=2001|1p=207–209|2a1=Wong|2y=2017|2p=49}} This kind of argument is also known as "argument from commitment". |

|||

The earlier notion of ''ad hominem'' arguments would be maintained among later Catholic Aristotelian scholastics, into the 19th century and even the 20th century. For instance, the Dominican friar and Cardinal, [[Tommaso Maria Zigliara]], doubtlessly drawing on earlier scholastic discussions, distinguished between absolute and relative demonstrations, referring to the latter as ''ad hominem'' arguments: “An ‘absolute’ demonstration is ''one which proceeds from premises whose truth we admit and assume in order to then draw an inference, absolutely speaking,'' as when we demonstrate the real existence of God on the basis of the contingent character of creatures, and other such demonstrations. However, a ''relative'' (that is, ''ad hominem'') demonstration is ''one which proceeds from principles which are admitted by the person we are arguing against and which we assume for the sake of refutation, setting aside the question of the truth of such principles,'' as when someone assumes principles admitted by materialists or by rationalists, in order to convince them that their doctrine is false.”{{sfn|Zigliara|1900|p=157}} |

|||

<!--Modern era--> |

|||

Italian [[Galileo Galilei]] and British philosopher [[John Locke]] also examined the argument from commitment, a form of the {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument, meaning examining an argument on the basis of whether it stands true to the principles of the person carrying the argument. In the mid-19th century, the modern understanding of the term {{lang|la|ad hominem}} started to take shape, with the broad definition given by English logician [[Richard Whately]]. According to Whately, {{lang|la|ad hominem}} arguments were "addressed to the peculiar circumstances, character, avowed opinions, or past conduct of the individual".{{sfn|Walton|2001|pp=208–210}} |

|||

<!--Hablin and contemporary--> |

<!--Hablin and contemporary--> |

||

Over time, the term acquired a different meaning; by the beginning of the 20th century, it was linked to a logical fallacy, in which a debater, instead of disproving an argument, attacked their opponent. This approach was also popularized in philosophical textbooks of the mid-20th century, and it was challenged by |

Over time, the term acquired a different meaning; by the beginning of the 20th century, it was linked to a [[logical fallacy]], in which a debater, instead of disproving an argument, attacked their opponent. This approach was also popularized in philosophical textbooks of the mid-20th century, and it was challenged by Australian philosopher [[Charles Leonard Hamblin]] in the second half of the 20th century. In a detailed work, he suggested that the inclusion of a statement against a person in an argument does not necessarily make it a fallacious argument since that particular phrase is not a premise that leads to a conclusion. While Hablin's criticism was not widely accepted, Canadian philosopher [[Douglas N. Walton]] examined the fallaciousness of the {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument even further.{{sfn|van Eemeren|Grootendorst|2015|pp=615–626}} Nowadays, except within specialized philosophical usaɡe, use of the term {{lang|la|ad hominem}} signifies a straight attack at the character and ethos of a person, in an attempt to refute their argument.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=210}} |

||

== Terminology == |

== Terminology == |

||

The Latin phrase {{lang|la|argumentum ad hominem}} stands for 'argument against the person'.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|p=91}} {{lang|la|Ad}} here means 'against' but could also mean 'to' or 'towards'.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=71–72}} |

|||

The terms {{lang|la|ad mulierem}} and {{lang|la|ad feminam}} have been used specifically when the person receiving the criticism is female{{sfnm|1a1=Olivesi|1y=2010|2a1=Sommers|2y=1991}} but the term {{lang|la|hominem}} (accusative of {{lang|la|homo}}) was gender-neutral in Latin.{{sfn|Lewis|Short|1879|p=859-860}} |

|||

The Latin phrase ''argumentum ad hominem'' stands for "argument against the person".{{sfn|Tindale|2007|p=91}} "Ad" corresponds to "against" but it could also mean "to" or "towards".{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=71–72}} |

|||

== Types of ''ad hominem'' arguments == |

|||

The terms ''ad mulierem'' and ''ad feminam'' have been used specifically when the person receiving the criticism is female.{{sfnm|1a1=Olivesi|1y=2010|2a1=Sommers|2y=1991}} |

|||

== Types of ad hominem arguments == |

|||

===Fallacious types of ad hominem arguments=== |

|||

[[File:Graham's Hierarchy of Disagreement.svg|440px|thumb|Abusive ''Ad hominem'' lies near the bottom end of [[Graham's Hierarchy of Disagreement]]]] |

|||

{{see also|List of fallacies}} |

{{see also|List of fallacies}} |

||

Fallacious |

Fallacious {{lang|la|ad hominem}} reasoning is categorized among [[informal fallacies]], more precisely as a [[genetic fallacy]], a subcategory of [[fallacies of irrelevance]].{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=2008|1p=190|2a1=Bowell|2a2=Kemp|2y=2010|2pp=201–213|3a1=Copi|3y=1986|3pp=112–113}} |

||

{{lang|la|Ad hominem}} fallacies can be separated into various types, such as {{lang|la|tu quoque}}, circumstantial {{lang|la|ad hominem}}, guilt by association, and abusive {{lang|la|ad hominem}}. All of them are similar to the general scheme of {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument, that is instead of dealing with the essence of someone's argument or trying to refute it, the interlocutor is attacking the character of the proponent of the argument and concluding that it is a sufficient reason to drop the initial argument.{{sfn|van Eemeren|2001|p=142}} |

|||

==== Circumstantial ==== |

|||

{{main|Bulverism}} |

|||

''Circumstantial ad hominem'' is an attack on the [[bias]] of a source. It points out that someone is in a circumstance (for instance, their job, wealth, property, or relations) such that they are disposed to take a particular position. A simple example is: a father may tell his daughter not to start smoking because she will damage her health, and she may point out that he is or was a smoker. This does not alter the fact that smoking might cause various diseases. Her father's inconsistency is not a proper reason to reject his claim.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=211}} |

|||

=== ''Tu quoque'' === |

|||

Circumstantial ''ad hominem'' arguments are not necessarily fallacious. They can be fallacious because a disposition to make a certain argument does not make the argument invalid (this overlaps with the genetic fallacy - an argument that a claim is incorrect due to its source). They can also be sound arguments if the premises are correct and the bias is relevant to the argument.{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=1998|1pp=18–21|2a1=Wrisley|2y=2019|2pp=77–78}} This could be the case when someone (A) attacks the personality of another person (B), making an argument (a) while the personality of B is relevant to argument a, for example, B speaks from their position as an [[authority figure]]. |

|||

{{Main|Tu quoque}} |

|||

{{lang|la|Ad hominem tu quoque}} (literally 'you also') is a response to an {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument that itself goes {{lang|la|ad hominem}}.{{sfnm|1a1=Wrisley|1y=2019|1p=88|2a1=Walton|2y=2015|2pp=431–435|3a1=Lavery|3a2=Hughes|3y=2008|3p=132}} |

|||

=====Appeal to motive===== |

|||

{{main|Appeal to motive}} |

|||

''[[Appeal to motive]]'' is a special case of the ''ad hominem'' circumstantial argument in which an argument is challenged by calling into question the motives of its proposer. |

|||

{{lang|la|Tu quoque}} appears as: |

|||

=====''Ergo decedo''===== |

|||

{{main|Ergo decedo}} |

|||

''[[Ergo decedo]]''', [[Latin]] for "therefore leave" or "then go off", a truncation of ''argumentum ergo decedo'', also known as the ''traitorous critic fallacy'',<ref name=Copi>{{cite book |last= M. Copi |first=Irving |title=Introduction to Logic|year=2010|edition=14th }}</ref> denotes responding to the criticism of a critic by implying that the critic is motivated by undisclosed favorability or affiliation to an [[Ingroups and outgroups|out-group]], rather than responding to the criticism itself. The fallacy implicitly alleges that the critic does not appreciate the [[tradition|values and customs]] of the criticized group or is [[treason|traitorous]], and thus suggests that the critic should avoid the question or topic entirely, typically by leaving the criticized group.<ref name=Taylor>{{cite book |author-link=Charles Taylor (philosopher) |last=Taylor |first=Charles |title=Philosophical Arguments |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=1997}}</ref> |

|||

* A makes a claim ''a''. |

|||

==== Guilt by association ==== |

|||

* B attacks the character of A by claiming they hold negative property ''x''. |

|||

{{main|Association fallacy}} |

|||

* A defends themself by attacking B, saying they also hold the same property ''x''.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|p=89}} |

|||

Guilt by association, that is accusing an arguer because of his alleged connection with a discredited person or group, can sometimes also be a type of ''ad hominem'' fallacy when the argument attacks a source because of the similarity between the views of someone making an argument and other proponents of the argument.{{sfn|Walton|1998|pp=18–21}} |

|||

An example given by professor George Wrisley to illustrate the above is: |

|||

This form of the argument is as follows:{{sfn|Walton|1998|pp=18–21}} |

|||

# Individual S makes claim C. |

|||

# Individual S is also associated with Group G, who has an unfavorable reputation |

|||

# Therefore, individual S and his views are questionable. |

|||

<blockquote>A businessman and a politician are giving a lecture at a university about how good his company is and how nicely the system works. A student asks him "Is it true that you and your company are selling weapons to third world rulers who use those arms against their own people?" and the businessman replies "Is it true that your university gets funding by the same company that you are claiming is selling guns to those countries? You are not a white dove either". The student's {{lang|la|ad hominem}} accusation is not fallacious, as it is relevant to the narrative the businessman is trying to project. On the other hand, the businessman's attack on the student (that is, the student being inconsistent) is irrelevant to the opening narrative. So the businessman's {{lang|la|tu quoque}} response is fallacious.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=89–91}}</blockquote> |

|||

Academic Leigh Kolb gives as an example that the [[United States presidential election, 2008|2008 US vice‐presidential]] candidate [[Sarah Palin]] attacked [[Barack Obama]] for having worked with [[Bill Ayers]], who had been a leader in the [[Weather Underground]] terrorist group in the 1960s. Despite Obama denouncing every act of terrorism, he was still associated by his opponents with terrorism.{{sfn|Kolb|2019|pp=351–352}} |

|||

Canadian philosopher [[Christopher Tindale]] approaches somewhat different the {{lang|la|tu quoque}} fallacy. According to Tindale, a {{lang|la|tu quoque}} fallacy appears when a response to an argument is made on the history of the arguer. This argument is also invalid because it does not disprove the premise; if the premise is true, then source A may be a [[hypocrite]] or even changed their mind, but this does not make the statement less credible from a logical perspective. A common example, given by Tindale, is when a doctor advises a patient to lose weight, but the patient argues that there is no need for him to go on a diet because the doctor is also overweight.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|pp=94–96}} |

|||

Guilt by association is frequently found in social and political debates. It also appears after major events (such as scandals and terrorism) linked to a specific group. An example, given also by Leigh Kolb, is the peak of attacks against Muslims in the US after the [[September 11 attacks]].{{sfn|Kolb|2019|pp=351–352}} |

|||

=== Circumstantial === |

|||

{{ |

{{Main|Bulverism}} |

||

''Ad hominem tu quoque'' (literally: "You also") is a response to a personal attack (or ''ad hominem'' argument) that itself is a personal attack.{{sfnm|1a1=Wrisley|1y=2019|1p=88|2a1=Walton|2y=2015|2pp= 431–435|3a1=Lavery|3a2=Hughes|3y=2008|3p=132}} |

|||

Circumstantial {{lang|la|ad hominem}}' points out that someone is in circumstances (for instance, their job, wealth, property, or relations) such that they are disposed to take a particular position. It constitutes an attack on the [[bias]] of a source. As with other types of the argument, the circumstantial {{lang|la|ad hominem}} could be fallacious or not. It could be fallacious because a disposition to make a certain argument does not make the argument invalid; this overlaps with the genetic fallacy (an argument that a claim is incorrect due to its source). But it also may be a sound argument, if the premises are correct and the bias is relevant to the argument.{{sfnm|1a1=Walton|1y=1998|1pp=18–21|2a1=Wrisley|2y=2019|2pp=77–78}} |

|||

''Tu quoque'' appears as: |

|||

*A makes a claim ''a''. |

|||

*B attacks the character of A by saying they hold a ''property x'', which is bad. |

|||

*A defends themself by attacking B, saying they also hold the same ''property x''.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|p=89}} |

|||

A simple example is: a father may tell his daughter not to start smoking because she will damage her health, and she may point out that he is or was a smoker. This does not alter the fact that smoking might cause various diseases. Her father's inconsistency is not a proper reason to reject his claim.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=211}} |

|||

Here is an example given by philosophy professor George Wrisley to illustrate the above: A businessman and politician is giving a lecture at a University about how good his company is and how nicely the system works. A student asks him "Is it true that you and your company are selling weapons to third world rulers who use those arms against their own people?" and the businessman replies "is it true that your university gets funding by the same company that you are claiming is selling guns to those countries? You are not a white dove either". The ''ad hominem'' accusation of the student is relevant to the narrative the businessman tries to project thus not fallacious. On the other hand, the attack on the student (that is, the student being inconsistent) is irrelevant to the opening narrative. So the businessman's ''tu quoque'' response is fallacious.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=89–91}} |

|||

Douglas N. Walton, philosopher and pundit on informal fallacies, argues that a circumstantial {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument can be non-fallacious. This could be the case when someone (A) attacks the personality of another person (B), making an argument (a) while the personality of B is relevant to argument ''a'', i.e. B talks as an [[authority figure]]. To illustrate this reasoning, Walton gives the example of a witness at a trial: if he had been caught lying and cheating in his own life, should the jury take his word for granted? No, according to Walton.{{sfn|Walton|2001|p=213}} |

|||

Canadian philosopher [[Christopher Tindale]] approaches somewhat different the ''tu quoque'' fallacy. According to Tindale, a ''tu quoque'' fallacy appears when a response to an argument is made on the history of the arguer. This argument is also invalid because it does not disprove the premise; if the premise is true, then source A may be a [[hypocrite]] or even changed their mind, but this does not make the statement less credible from a logical perspective. A common example, given by Tindale, is when a doctor advises a patient to lose weight, but the patient argues that there is no need for him to go on a diet because the doctor is also overweight.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|pp=94–96}} |

|||

=== Guilt by association === |

|||

{{main| |

{{main|Association fallacy}} |

||

Guilt by association, that is accusing an arguer because of his alleged connection with a discredited person or group, can sometimes also be a type of {{lang|la|ad hominem}} fallacy when the argument attacks a source because of the similarity between the views of someone making an argument and other proponents of the argument.{{sfn|Walton|1998|pp=18–21}} |

|||

{{see also|"And you are lynching Negroes"}} |

|||

''[[Whataboutism]]'', also known as ''whataboutery'', is a variant of the ''tu quoque'' logical fallacy that attempts to discredit an opponent's position by charging them with [[hypocrisy]] without directly refuting or disproving their argument.<ref name=OLD>{{citation |url=https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/whataboutism |title=whataboutism |work=[[Oxford Living Dictionaries]] |year=2017 |access-date=21 July 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170309142742/https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/whataboutism |archive-date=9 March 2017 |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |quote=Origin - 1990s: from the way in which counter-accusations may take the form of questions introduced by 'What about —?'. ... Also called ''whataboutery''}}</ref><ref name=zimmer-def>{{cite news |work=[[The Wall Street Journal]] |access-date=22 July 2017 |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-roots-of-the-what-about-ploy-1497019827 |first=Ben |last=Zimmer |author-link=Ben Zimmer |title=The Roots of the 'What About?' Ploy |date=9 June 2017 |quote="Whataboutism" is another name for the logical fallacy of "tu quoque" (Latin for "you also"), in which an accusation is met with a counter-accusation, pivoting away from the original criticism. The strategy has been a hallmark of Soviet and post-Soviet propaganda, and some commentators have accused President Donald Trump of mimicking Mr. Putin's use of the technique.}}</ref><ref>{{citation |url=http://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/whataboutism |title=whataboutism |work=[[Cambridge Dictionary]] |ref=none}}</ref> |

|||

This form of the argument is as follows:{{sfn|Walton|1998|pp=18–21}} |

|||

====Abusive ''ad hominem''==== |

|||

{{see also|Name calling|Verbal abuse}} |

|||

The term "ad hominem" is sometimes used to refer to abusive language which is not directly connected to an argument over a particular proposition. For example, a politician who refers to an opponent as "a crook", might be accused of arguing "ad hominem".{{sfn|Tindale|2007|pp=92–93}}{{sfn|Hansen|2019|loc= 1. The core fallacies}}{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=123}} |

|||

# Individual S makes claim C. |

|||

==== Poisoning the well ==== |

|||

# Individual S is also associated with Group G, who has an unfavorable reputation |

|||

{{main|Poisoning the well}} |

|||

# Therefore, individual S and his views are questionable. |

|||

''Poisoning the well'' (or attempting to ''poison the well'') is a type of informal fallacy where adverse information about a target is preemptively presented to an audience with the intention of discrediting or ridiculing something that the target person is about to say. The term was first used in the sense of an ''ad hominem'' by [[John Henry Newman]] in his work ''[[Apologia Pro Vita Sua]]'' (1864).<ref name="walton">{{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |date=1987 |title=Informal Fallacies: Towards a Theory of Argument Criticisms |series=Pragmatics & beyond companion series |volume=4 |location=Amsterdam; Philadelphia |publisher=[[John Benjamins Publishing]] |page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=BGwTc1DhylQC&pg=PA218 218] |isbn=1556190107 |oclc=14586031 }} See also: {{cite web |url=http://www.newmanreader.org/works/apologia65/preface.html |title=Newman Reader – Apologia (1865) – Preface |website=newmanreader.org}}</ref> The origin of the term lies in [[well poisoning]], an ancient wartime practice of pouring poison into sources of [[fresh water]] before an invading army, to diminish the attacked army's strength. |

|||

Academic Leigh Kolb gives as an example that the [[2008 United States presidential election|2008 US vice-presidential]] candidate [[Sarah Palin]] attacked [[Barack Obama]] for having worked with [[Bill Ayers]], who had been a leader in the [[Weather Underground]] terrorist group in the 1960s. Despite Obama denouncing every act of terrorism, he was still associated by his opponents with terrorism.{{sfn|Kolb|2019|pp=351–352}} |

|||

===Valid types of ad hominem arguments=== |

|||

Guilt by association is frequently found in social and political debates. It also appears after major events (such as scandals and terrorism) linked to a specific group. An example, given also by Leigh Kolb, is the peak of attacks against Muslims in the US after the [[September 11 attacks]].{{sfn|Kolb|2019|pp=351–352}} |

|||

==== Argument from commitment ==== |

|||

An ''ad hominem'' argument from commitment is a type of valid argument that employs, as a dialectical strategy, the exclusive utilization of the beliefs, convictions, and assumptions of those holding the position being argued against, i.e., arguments constructed on the basis of what other people hold to be true. This usage is generally only encountered in specialist philosophical usage or in pre-20th century usages.{{sfn|Merriam-Webster|2019|loc=note1}} This type of argument is also known as the ''ex concessis'' argument (Latin for "from what has been conceded already").{{sfn|Walton|2001}} |

|||

=== |

===Abusive ''ad hominem''=== |

||

{{see also|Name calling|Verbal abuse}} |

|||

Ad hominem arguments are relevant where the person being criticised is advancing arguments from authority, or testimony based on personal experience, rather than proposing a formal syllogism. [https://newscentral24x7.com/how-ad-hominem-arguments-can-demolish-appeals-to-authority/] |

|||

Abusive {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument (or direct {{lang|la|ad hominem}}) is associated with an attack to the character of the person carrying an argument. This kind of argument, besides usually being fallacious, is also counterproductive, as a proper dialogue is hard to achieve after such an attack.{{sfn|Tindale|2007|pp=92–93}}{{sfn|Hansen|2019|loc=1. The core fallacies}}{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=123}} |

|||

Key issues in examining an argument to determine whether it is an {{lang|la|ad hominem}} fallacy or not are whether the accusation against the person stands true or not, and whether the accusation is relevant to the argument. An example is a dialogue at the court, where the attorney cross-examines an eyewitness, bringing to light the fact that the witness was convicted in the past for lying. If the attorney's conclusion is that the witness is lying, that would be wrong. But if his argument would be that the witness should not be trusted, that would not be a fallacy.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=86–87}} |

|||

An example is a dialogue at the court, where the attorney cross-examines an eyewitness, bringing to light the fact that the witness was convicted in the past for lying. This might suggest the conclusion that the witness should not be trusted, which would not be a fallacy.{{sfn|Wrisley|2019|pp=86–87}} Related issues arise with arguments from authority. If a witness claiming to a medical expert asserts, on the basis of their expert knowledge, that a particular product is harmless, an opponent could make the ad hominem argument that the witness' expertise is less than claimed, or that the witness has been paid by the makers of the product. |

|||

=== Argument from commitment === |

|||

More complex issues arise in cases where the conclusion is merely probable rather than deducible with certainty. An advocate for a particular proposition might present a body of evidence supporting that proposition while ignoring evidence against it. Pointing out that the advocate is not neutral, but has a conflict of interest, is a valid form of ad hominem argument. |

|||

An {{lang|la|ad hominem}} argument from commitment is a type of valid argument that employs, as a dialectical strategy, the exclusive use of the beliefs, convictions, and assumptions of those holding the position being argued against, i.e., arguments constructed on the basis of what other people hold to be true. This usage is generally only encountered in specialist philosophical usage or in pre-20th century usages.{{sfn|Merriam-Webster|2019|loc=note1}} This type of argument is also known as the {{lang|la|ex concessis}} argument (Latin for 'from what has been conceded already').{{sfn|Walton|2001}} |

|||

== |

== Use in debates== |

||

{{lang|la|Ad hominem}} fallacies are considered to be uncivil and do not help creating a constructive atmosphere for dialogue to flourish.{{sfn|Weston|2018|p=82}} An {{lang|la|ad hominem}} attack is an attack on the character of the target who tends to feel the necessity to defend himself or herself from the accusation of being hypocritical. Walton has noted that it is so powerful of an argument that it is employed in many political debates. Since it is associated with negativity and dirty tricks, it has gained a bad fame, of being always fallacious.{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=122}} |

|||

Author Eithan Orkibi, having studied Israeli politics prior to elections, described two other forms of {{lang|la|ad hominem}} attacks that are common during election periods. They both depend on the [[collective memory]] shared by both proponents and the audience. The first is the "precedent {{lang|la|ad hominem}}", according to which the previous history of someone means that they do not fit for the office. It goes like this: "My opponent was (allegedly) wrong in the past, therefore he is wrong now". The second one is a behavioral {{lang|la|ad hominem}}: "my opponent was not decent in his arguments in the past, so he is not now either". These kinds of attacks are based on the inability of the audience to have a clear view of the amount of false statements by both parts of the debate.{{sfn|Orkibi|2018|pp=497–498}} |

|||

===Improper usage=== |

|||

Contrary to popular belief, merely insulting someone is not a fallacious ''ad hominem''. A character attack is only considered a fallacious ''ad hominem'' if it is used in exchange for a genuine argument.{{sfn|Walton|2008|p=170}} |

|||

Examples: |

|||

* Pure abuse: "B" says of an opponent "A", "You are a moron". In this case, there is no argument, only abuse. |

|||

* Fallacious: ''A'' makes an argument, ''B'' responds with "You are a moron and you are also ugly, you cannot possibly be correct". ''B'' has not offered a genuine response or argument, only abuse - this is fallacious. |

|||

* Non-Fallacious: ''A'' makes an argument'', B'' responds with "(Genuine refutation of ''A's'' argument), also you are a moron". While potentially childish, ''B'' has genuinely offered a response to ''A's'' argument and has just bolted on an insult. This is not a fallacy, as an insult or character attack was not ''exchanged'' for an argument; rather one was provided ''alongside'' of an argument''.'' |

|||

=== Usage in debates=== |

|||

''Ad hominem'' fallacies are considered to be uncivil and do not help creating a constructive atmosphere for dialogue to flourish.{{sfn|Weston|2018|p=82}} An ''ad hominem'' attack is an attack on the character of the target who tends to feel the necessity to defend himself or herself from the accusation of being hypocritical. Walton has noted that it is so powerful of an argument that it is employed in many political debates. Since it is associated with negativity and dirty tricks, ''ad hominem'' attackes have erroneously been assumed to always be fallacious.{{sfn|Walton|2006|p=122}} |

|||

Eithan Orkibi describes two forms of ''ad hominem'' attacks that are common during election periods. The first is the ''precedent ad hominem'', according to which the previous history of someone means that they do not fit for the office. For example: "My opponent was (allegedly) wrong in the past, therefore he is wrong now". The second one is a ''behavioral ad hominem'': "My opponent was not decent in his arguments in the past, so he is not now either". These kinds of attacks are based on the inability of the audience to have a clear view of the amount of false statements by both parts of the debate.{{sfn|Orkibi|2018|pp=497–498}} |

|||

== Criticism as a fallacy == |

== Criticism as a fallacy == |

||

Walton has argued that |

Walton has argued that {{lang|la|ad hominem}} reasoning is not always fallacious, and that in some instances, questions of personal conduct, character, motives, etc., are legitimate and relevant to the issue,{{sfn|Walton|2008|p=170}} as when it directly involves hypocrisy, or actions contradicting the subject's words. |

||

The philosopher [[Charles Taylor (philosopher)|Charles Taylor]] has argued that |

The philosopher [[Charles Taylor (philosopher)|Charles Taylor]] has argued that {{lang|la|ad hominem}} reasoning (discussing facts about the speaker or author relative to the value of his statements) is essential to understanding certain moral issues due to the connection between individual persons and morality (or moral claims), and contrasts this sort of reasoning with the [[apodictic]] reasoning (involving facts beyond dispute or clearly established) of philosophical naturalism.{{sfn|Taylor|1995|pp=34–60}} |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

{{Portal|Philosophy}} |

{{Portal|Philosophy}} |

||

{{div col|colwidth=20em}} |

{{div col|colwidth=20em}} |

||

* [[ |

* "[[And you are lynching Negroes]]" |

||

* [[Argument from authority]] |

|||

* [[Appeal to emotion]] |

* [[Appeal to emotion]] |

||

* [[Appeal to motive]] |

|||

* ''[[The Art of Being Right]]'' |

|||

* [[Character assassination]] |

* [[Character assassination]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Dogpiling (Internet)]] |

||

* {{lang|la|[[Ergo decedo]]}} |

|||

* [[Fair Game (Scientology)]] |

|||

* [[Fair game (Scientology)]] |

|||

* [[Fake news]] |

* [[Fake news]] |

||

* [[False equivalence]] |

|||

* [[Fundamental attribution error]] |

* [[Fundamental attribution error]] |

||

* [[Gaslighting]] |

* [[Gaslighting]] |

||

* [[Godwin's law]] |

|||

* [[Hostile witness]] |

* [[Hostile witness]] |

||

* [[List of fallacies]] |

|||

* [[Negative campaigning]] |

* [[Negative campaigning]] |

||

* [[Poisoning the well]] |

|||

* [[Presumption of guilt]] |

* [[Presumption of guilt]] |

||

* [[Race card]] |

* [[Race card]] |

||

| Line 142: | Line 124: | ||

* [[Straw man]] |

* [[Straw man]] |

||

* [[Tone policing]] |

* [[Tone policing]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Whataboutism]] |

||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

| Line 150: | Line 132: | ||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

{{refbegin|colwidth=30em}} |

{{refbegin|colwidth=30em}} |

||

*{{cite book|last1=Bowell|first1=Tracy|last2=Kemp|first2=Gary|title=Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide|year=2010|publisher=Routledge|location=Abingdon, Oxon|isbn=978-0-415-47183-1}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Bowell |first1=Tracy |last2=Kemp |first2=Gary |title=Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide |year=2010 |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, Oxon |isbn=978-0-415-47183-1}} |

||

*{{cite book|last=Copi|first=Irving M.|title=Informal Logic|isbn=978-0-02-324940-2|publisher=Macmillan|year=1986}} |

* {{cite book |last=Copi |first=Irving M. |title=Informal Logic |isbn=978-0-02-324940-2 |publisher=Macmillan |year=1986}} |

||

*{{cite encyclopedia |last= |

* {{cite encyclopedia |last=Hansen |first=Hans |author-link= |editor-last=Zalta |editor-first=Edward N. |editor-link=Edward N. Zalta |encyclopedia=[[The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |title=Fallacies |trans-title= |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/fallacies/ |access-date= |language= |edition= |year=2019 |publisher= |series= |volume= |location= |id= |isbn= |oclc= |doi= |pages= |archive-url= |archive-date= |url-status= |quote=}} |

||

* {{cite book|last=Kolb|first=Leigh|chapter= |

* {{cite book |last=Kolb |first=Leigh |chapter=Guilt by Association |pages=351–353 |editor1=Robert Arp |editor2=Steven Barbone |editor3=Michael Bruce |doi=10.1002/9781119165811.ch83 |year=2019 |title=Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy |publisher=Wiley Blackwell |isbn=978-1-119-16580-4 |s2cid=187211421}} |

||

* {{cite book|last1=Lavery|first1=Jonathan |last2=Hughes|first2=Willam |title=Critical Thinking, fifth edition: An Introduction to the Basic Skills|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xL-qf5Hbkm0C&pg=PA132|date=27 May 2008|publisher=Broadview Press|isbn=978-1-77048-111-4}} |

* {{cite book |last1=Lavery |first1=Jonathan |last2=Hughes |first2=Willam |title=Critical Thinking, fifth edition: An Introduction to the Basic Skills |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xL-qf5Hbkm0C&pg=PA132 |date=27 May 2008 |publisher=Broadview Press |isbn=978-1-77048-111-4}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=Charlton |last2=Short |first2=Charles |title=A Latin Dictionary |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0059:entry=homo |date=1879 |publisher=Nigel Gourlay |isbn=9781999855789}} |

|||

* {{cite web | title=Definition of Ad Hominem | last= Merriam-Webster | year=2019 | url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ad+hominem| access-date=2020-01-08}} |

|||

* {{cite web |title=Definition of Ad Hominem |last=Merriam-Webster |year=2019 |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ad+hominem |access-date=2020-01-08}} |

|||

*{{Cite journal|last=Olivesi|first=Aurélie|date=2010-04-05|title=L'interrogation sur la compétence politique en 2007 : une question de genre ?|url=https://journals.openedition.org/quaderni/486|journal=Quaderni|language=fr|issue=72|pages=59–74|doi=10.4000/quaderni.486|issn=0987-1381|doi-access=free}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Nuchelmans |first=Gäbriel |chapter=On the Fourfold Root of the ''Argumentum ad Hominem'' |year=1993 |title=Empirical Logic and Public Debate |editor-last1=Krabbe |editor-first1=Erik C. W. |editor-last2=Dalitz |editor-first2=Renée José |editor-last3=Smit |editor-first3=Pier}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last=Orkibi | first=Eithan | title=Precedential Ad Hominem in Polemical Exchange: Examples from the Israeli Political Debate | journal=Argumentation | volume=32 | issue=4 | date=2018-02-27 | issn=0920-427X | doi=10.1007/s10503-018-9453-2 | pages=485–499 | s2cid=149120204 }} |

|||

*{{Cite journal |

* {{Cite journal |last=Olivesi |first=Aurélie |date=2010-04-05 |title=L'interrogation sur la compétence politique en 2007 : une question de genre ? |url=https://journals.openedition.org/quaderni/486 |journal=Quaderni |language=fr |issue=72 |pages=59–74 |doi=10.4000/quaderni.486 |issn=0987-1381 |doi-access=free}} |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Orkibi |first=Eithan |title=Precedential Ad Hominem in Polemical Exchange: Examples from the Israeli Political Debate |journal=Argumentation |volume=32 |issue=4 |date=2018-02-27 |issn=0920-427X |doi=10.1007/s10503-018-9453-2 |pages=485–499 |s2cid=254261480}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Taylor |first=Charles|author-link=Charles Taylor (philosopher) |title=Philosophical Arguments |year=1995 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=9780674664760 |pages=34–60 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iqtLAsIBZ2sC&q=explanation+and+practical+reason+charles+taylor&pg=PA34 |chapter=Explanation and Practical Reason}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal |last=Sommers |first=Christina |date=March 1991 |title=Argumentum ad feminam |journal=Journal of Social Philosophy |language=en |volume=22 |issue=1 |pages=5–19 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9833.1991.tb00016.x |issn=0047-2786}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Tindale|first=Christopher W. |title=Fallacies and Argument Appraisal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ved8b9Cr8Z8C|date=22 January 2007|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-46184-9}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last= |

* {{cite book |last=Taylor |first=Charles |author-link=Charles Taylor (philosopher) |title=Philosophical Arguments |year=1995 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=9780674664760 |pages=34–60 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iqtLAsIBZ2sC&dq=explanation+and+practical+reason+charles+taylor&pg=PA34 |chapter=Explanation and Practical Reason}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Tindale |first=Christopher W. |title=Fallacies and Argument Appraisal |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ved8b9Cr8Z8C |date=22 January 2007 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-46184-9}} |

|||

* {{cite book | last1=van Eemeren | first1=Frans H. |author-link=Frans H. van Eemeren| last2=Grootendorst | first2=Rob | title=Argumentation Library | chapter=The History of the Argumentum Ad Hominem Since the Seventeenth Century | publisher=Springer International Publishing | location=Cham | year=2015 | isbn=978-3-319-20954-8 | issn=1566-7650 | doi=10.1007/978-3-319-20955-5_32 }} |

|||

*{{cite book |last= |

* {{cite book |last=van Eemeren |first=F. H. |author-link=Frans H. van Eemeren |title=Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JpgfSPmaVFkC |year=2001 |publisher=Amsterdam University Press |isbn=978-90-5356-523-0}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=van Eemeren |first1=Frans H. |author-link=Frans H. van Eemeren |last2=Grootendorst |first2=Rob |title=Argumentation Library |chapter=The History of the Argumentum Ad Hominem Since the Seventeenth Century |publisher=Springer International Publishing |location=Cham |year=2015 |isbn=978-3-319-20954-8 |issn=1566-7650 |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-20955-5_32}} |

|||

* {{cite journal|last=Walton |first=Douglas N.|author-link=Douglas N. Walton| journal = Argumentation|year= 2001|volume=15|pages= 207–221 |url=http://www.dougwalton.ca/papers%20in%20pdf/01roots.pdf|title=Argumentation Schemes and Historical Origins of the Circumstantial Ad Hominem Argument|issue=2|doi=10.1023/A:1011120100277|s2cid=16864574|issn=0920-427X }} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Walton|first= |

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |title=Ad Hominem Arguments |publisher=University of Alabama Press |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-8173-0922-0}} |

||

*{{cite |

* {{cite journal |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |journal=Argumentation |year=2001 |volume=15 |pages=207–221 |url=http://www.dougwalton.ca/papers%20in%20pdf/01roots.pdf |title=Argumentation Schemes and Historical Origins of the Circumstantial Ad Hominem Argument |issue=2 |doi=10.1023/A:1011120100277 |s2cid=16864574 |issn=0920-427X}} |

||

*{{cite book |last=Walton|first= |

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |title=Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BpRUGM8nOdwC |year=2006 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-82319-7}} |

||

*{{cite book|last= |

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |title=Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach |year=2008 |publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Walton |first=Douglas N. |author-link=Douglas N. Walton |chapter=informal logic |editor=Audi Robert |title=The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OfoNngEACAAJ |date=27 April 2015 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-107-01505-0}} |

|||

*{{cite thesis |last= Wong|first= Andrew David|date= 2017|title= Unmitigated Skepticism: The Nature and Scope of Pyrrhonism |publisher= [[University of California]]|url=https://escholarship.org/content/qt6fk1n2b1/qt6fk1n2b1.pdf }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Weston |first=Anthony |title=A Rulebook for Arguments |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XhVNDwAAQBAJ |year=2018 |publisher=Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated |isbn=978-1-62466-655-1}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last= Wrisley|first=George|editor1= Robert Arp|editor2= Steven Barbone|editor3= Michael Bruce|chapter=Ad Hominem: Circumstantial| year=2019|title=Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy|publisher= Wiley Blackwell|isbn=978-1-119-16580-4|pages=77–82|doi=10.1002/9781119165811.ch9}} |

|||

* {{cite thesis |last=Wong |first=Andrew David |date=2017 |title=Unmitigated Skepticism: The Nature and Scope of Pyrrhonism |type= |chapter= |publisher=[[University of California]] |docket= |oclc= |url=https://escholarship.org/content/qt6fk1n2b1/qt6fk1n2b1.pdf |access-date=}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Zigliara|first=Tommaso|edition=12|title=Summa philosophica in usum scholarum|volume=1|year=1900|location=Paris|publisher=Briguet|author-link=Tommaso Maria Zigliara}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Wrisley |first=George |editor1=Robert Arp |editor2=Steven Barbone |editor3=Michael Bruce |chapter=Ad Hominem: Circumstantial |year=2019 |title=Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy |publisher=Wiley Blackwell |isbn=978-1-119-16580-4 |pages=77–82 |doi=10.1002/9781119165811.ch9 |s2cid=171674012}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

| Line 178: | Line 161: | ||

* {{PhilPapers|search|ad_hominem}} |

* {{PhilPapers|search|ad_hominem}} |

||

* [http://philosophy.lander.edu/logic/person.html Argumentum Ad Hominem] |

* [http://philosophy.lander.edu/logic/person.html Argumentum Ad Hominem] |

||

* [https://fallacycheck.com/fallacy/ad%20hominem Ad hominem] at Fallacy Check, with [https://fallacycheck.com/analyses/ad%20hominem examples] |

|||

{{Fallacies}} |

{{Fallacies}} |

||

{{Propaganda}} |

{{Propaganda}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Genetic fallacies]] |

[[Category:Genetic fallacies]] |

||

[[Category:Informal fallacies]] |

|||

[[Category:Latin logical phrases]] |

[[Category:Latin logical phrases]] |

||

[[Category:Latin words and phrases]] |

[[Category:Latin words and phrases]] |

||

[[Category:Propaganda techniques]] |

[[Category:Propaganda techniques]] |

||

[[Category:Pyrrhonism]] |

|||

[[Category:Rhetoric]] |

[[Category:Rhetoric]] |

||

[[Category:Informal fallacies]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 15:18, 29 December 2024

Ad hominem (Latin for 'to the person'), short for argumentum ad hominem, refers to several types of arguments that are usually fallacious. Often currently this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other attribute of the person making an argument rather than the substance of the argument itself. This avoids genuine debate by creating a diversion often using a totally irrelevant, but often highly charged attribute of the opponent's character or background. The most common form of this fallacy is "A" makes a claim of "fact", to which "B" asserts that "A" has a personal trait, quality or physical attribute that is repugnant thereby going off-topic, and hence "B" concludes that "A" has their "fact" wrong – without ever addressing the point of the debate. Many contemporary politicians routinely use ad hominem attacks, some of which can be encapsulated to a derogatory nickname for a political opponent used instead of political argumentation. (But modern democracy requires that voters make character judgements of representatives, so opponents may reasonably criticize their character and motives.)

Other uses of the term ad hominem are more traditional, referring to arguments tailored to fit a particular audience, and may be encountered in specialized philosophical usage. These typically refer to the dialectical strategy of using the target's own beliefs and arguments against them, while not agreeing with the validity of those beliefs and arguments. Ad hominem arguments were first studied in ancient Greece; John Locke revived the examination of ad hominem arguments in the 17th century.

A common misconception is that an ad hominem attack is synonymous with an insult. This is not true, although some ad hominem arguments may be insulting by the person receiving the argument.

History

[edit]

The various types of ad hominem arguments have been known in the West since at least the ancient Greeks. Aristotle, in his work Sophistical Refutations, detailed the fallaciousness of putting the questioner but not the argument under scrutiny.[2] His description was somewhat different from the modern understanding, referring to a class of sophistry that applies an ambiguously worded question about people to a specific person. The proper refutation, he wrote, is not to debate the attributes of the person (solutio ad hominem) but to address the original ambiguity.[3] Many examples of ancient non-fallacious ad hominem arguments are preserved in the works of the Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus. In these arguments, the concepts and assumptions of the opponents are used as part of a dialectical strategy against them to demonstrate the unsoundness of their own arguments and assumptions. In this way, the arguments are to the person (ad hominem), but without attacking the properties of the individuals making the arguments.[4] This kind of argument is also known as "argument from commitment".

Italian Galileo Galilei and British philosopher John Locke also examined the argument from commitment, a form of the ad hominem argument, meaning examining an argument on the basis of whether it stands true to the principles of the person carrying the argument. In the mid-19th century, the modern understanding of the term ad hominem started to take shape, with the broad definition given by English logician Richard Whately. According to Whately, ad hominem arguments were "addressed to the peculiar circumstances, character, avowed opinions, or past conduct of the individual".[5]

Over time, the term acquired a different meaning; by the beginning of the 20th century, it was linked to a logical fallacy, in which a debater, instead of disproving an argument, attacked their opponent. This approach was also popularized in philosophical textbooks of the mid-20th century, and it was challenged by Australian philosopher Charles Leonard Hamblin in the second half of the 20th century. In a detailed work, he suggested that the inclusion of a statement against a person in an argument does not necessarily make it a fallacious argument since that particular phrase is not a premise that leads to a conclusion. While Hablin's criticism was not widely accepted, Canadian philosopher Douglas N. Walton examined the fallaciousness of the ad hominem argument even further.[6] Nowadays, except within specialized philosophical usaɡe, use of the term ad hominem signifies a straight attack at the character and ethos of a person, in an attempt to refute their argument.[7]

Terminology

[edit]The Latin phrase argumentum ad hominem stands for 'argument against the person'.[8] Ad here means 'against' but could also mean 'to' or 'towards'.[9]

The terms ad mulierem and ad feminam have been used specifically when the person receiving the criticism is female[10] but the term hominem (accusative of homo) was gender-neutral in Latin.[11]

Types of ad hominem arguments

[edit]Fallacious ad hominem reasoning is categorized among informal fallacies, more precisely as a genetic fallacy, a subcategory of fallacies of irrelevance.[12]

Ad hominem fallacies can be separated into various types, such as tu quoque, circumstantial ad hominem, guilt by association, and abusive ad hominem. All of them are similar to the general scheme of ad hominem argument, that is instead of dealing with the essence of someone's argument or trying to refute it, the interlocutor is attacking the character of the proponent of the argument and concluding that it is a sufficient reason to drop the initial argument.[13]

Tu quoque

[edit]Ad hominem tu quoque (literally 'you also') is a response to an ad hominem argument that itself goes ad hominem.[14]

Tu quoque appears as:

- A makes a claim a.

- B attacks the character of A by claiming they hold negative property x.

- A defends themself by attacking B, saying they also hold the same property x.[15]

An example given by professor George Wrisley to illustrate the above is:

A businessman and a politician are giving a lecture at a university about how good his company is and how nicely the system works. A student asks him "Is it true that you and your company are selling weapons to third world rulers who use those arms against their own people?" and the businessman replies "Is it true that your university gets funding by the same company that you are claiming is selling guns to those countries? You are not a white dove either". The student's ad hominem accusation is not fallacious, as it is relevant to the narrative the businessman is trying to project. On the other hand, the businessman's attack on the student (that is, the student being inconsistent) is irrelevant to the opening narrative. So the businessman's tu quoque response is fallacious.[16]

Canadian philosopher Christopher Tindale approaches somewhat different the tu quoque fallacy. According to Tindale, a tu quoque fallacy appears when a response to an argument is made on the history of the arguer. This argument is also invalid because it does not disprove the premise; if the premise is true, then source A may be a hypocrite or even changed their mind, but this does not make the statement less credible from a logical perspective. A common example, given by Tindale, is when a doctor advises a patient to lose weight, but the patient argues that there is no need for him to go on a diet because the doctor is also overweight.[17]

Circumstantial

[edit]Circumstantial ad hominem' points out that someone is in circumstances (for instance, their job, wealth, property, or relations) such that they are disposed to take a particular position. It constitutes an attack on the bias of a source. As with other types of the argument, the circumstantial ad hominem could be fallacious or not. It could be fallacious because a disposition to make a certain argument does not make the argument invalid; this overlaps with the genetic fallacy (an argument that a claim is incorrect due to its source). But it also may be a sound argument, if the premises are correct and the bias is relevant to the argument.[18]

A simple example is: a father may tell his daughter not to start smoking because she will damage her health, and she may point out that he is or was a smoker. This does not alter the fact that smoking might cause various diseases. Her father's inconsistency is not a proper reason to reject his claim.[19]

Douglas N. Walton, philosopher and pundit on informal fallacies, argues that a circumstantial ad hominem argument can be non-fallacious. This could be the case when someone (A) attacks the personality of another person (B), making an argument (a) while the personality of B is relevant to argument a, i.e. B talks as an authority figure. To illustrate this reasoning, Walton gives the example of a witness at a trial: if he had been caught lying and cheating in his own life, should the jury take his word for granted? No, according to Walton.[20]

Guilt by association

[edit]Guilt by association, that is accusing an arguer because of his alleged connection with a discredited person or group, can sometimes also be a type of ad hominem fallacy when the argument attacks a source because of the similarity between the views of someone making an argument and other proponents of the argument.[21]

This form of the argument is as follows:[21]

- Individual S makes claim C.

- Individual S is also associated with Group G, who has an unfavorable reputation

- Therefore, individual S and his views are questionable.

Academic Leigh Kolb gives as an example that the 2008 US vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin attacked Barack Obama for having worked with Bill Ayers, who had been a leader in the Weather Underground terrorist group in the 1960s. Despite Obama denouncing every act of terrorism, he was still associated by his opponents with terrorism.[22]

Guilt by association is frequently found in social and political debates. It also appears after major events (such as scandals and terrorism) linked to a specific group. An example, given also by Leigh Kolb, is the peak of attacks against Muslims in the US after the September 11 attacks.[22]

Abusive ad hominem

[edit]Abusive ad hominem argument (or direct ad hominem) is associated with an attack to the character of the person carrying an argument. This kind of argument, besides usually being fallacious, is also counterproductive, as a proper dialogue is hard to achieve after such an attack.[23][24][25]

Key issues in examining an argument to determine whether it is an ad hominem fallacy or not are whether the accusation against the person stands true or not, and whether the accusation is relevant to the argument. An example is a dialogue at the court, where the attorney cross-examines an eyewitness, bringing to light the fact that the witness was convicted in the past for lying. If the attorney's conclusion is that the witness is lying, that would be wrong. But if his argument would be that the witness should not be trusted, that would not be a fallacy.[26]

Argument from commitment

[edit]An ad hominem argument from commitment is a type of valid argument that employs, as a dialectical strategy, the exclusive use of the beliefs, convictions, and assumptions of those holding the position being argued against, i.e., arguments constructed on the basis of what other people hold to be true. This usage is generally only encountered in specialist philosophical usage or in pre-20th century usages.[27] This type of argument is also known as the ex concessis argument (Latin for 'from what has been conceded already').[28]

Use in debates

[edit]Ad hominem fallacies are considered to be uncivil and do not help creating a constructive atmosphere for dialogue to flourish.[29] An ad hominem attack is an attack on the character of the target who tends to feel the necessity to defend himself or herself from the accusation of being hypocritical. Walton has noted that it is so powerful of an argument that it is employed in many political debates. Since it is associated with negativity and dirty tricks, it has gained a bad fame, of being always fallacious.[30]

Author Eithan Orkibi, having studied Israeli politics prior to elections, described two other forms of ad hominem attacks that are common during election periods. They both depend on the collective memory shared by both proponents and the audience. The first is the "precedent ad hominem", according to which the previous history of someone means that they do not fit for the office. It goes like this: "My opponent was (allegedly) wrong in the past, therefore he is wrong now". The second one is a behavioral ad hominem: "my opponent was not decent in his arguments in the past, so he is not now either". These kinds of attacks are based on the inability of the audience to have a clear view of the amount of false statements by both parts of the debate.[31]

Criticism as a fallacy

[edit]Walton has argued that ad hominem reasoning is not always fallacious, and that in some instances, questions of personal conduct, character, motives, etc., are legitimate and relevant to the issue,[32] as when it directly involves hypocrisy, or actions contradicting the subject's words.

The philosopher Charles Taylor has argued that ad hominem reasoning (discussing facts about the speaker or author relative to the value of his statements) is essential to understanding certain moral issues due to the connection between individual persons and morality (or moral claims), and contrasts this sort of reasoning with the apodictic reasoning (involving facts beyond dispute or clearly established) of philosophical naturalism.[33]

See also

[edit]- "And you are lynching Negroes"

- Argument from authority

- Appeal to emotion

- Appeal to motive

- The Art of Being Right

- Character assassination

- Dogpiling (Internet)

- Ergo decedo

- Fair game (Scientology)

- Fake news

- False equivalence

- Fundamental attribution error

- Gaslighting

- Godwin's law

- Hostile witness

- List of fallacies

- Negative campaigning

- Poisoning the well

- Presumption of guilt

- Race card

- Red herring

- Reputation

- Shooting the messenger

- Smear campaign

- Straw man

- Tone policing

- Whataboutism

References

[edit]- ^ Walton 2001, p. 208; Tindale 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Tindale 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Nuchelmans 1993, p. 43.

- ^ Walton 2001, p. 207–209; Wong 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Walton 2001, pp. 208–210.

- ^ van Eemeren & Grootendorst 2015, pp. 615–626.

- ^ Walton 2001, p. 210.

- ^ Tindale 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Wrisley 2019, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Olivesi 2010; Sommers 1991.

- ^ Lewis & Short 1879, p. 859-860.

- ^ Walton 2008, p. 190; Bowell & Kemp 2010, pp. 201–213; Copi 1986, pp. 112–113.

- ^ van Eemeren 2001, p. 142.

- ^ Wrisley 2019, p. 88; Walton 2015, pp. 431–435; Lavery & Hughes 2008, p. 132.

- ^ Wrisley 2019, p. 89.

- ^ Wrisley 2019, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Tindale 2007, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Walton 1998, pp. 18–21; Wrisley 2019, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Walton 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Walton 2001, p. 213.

- ^ a b Walton 1998, pp. 18–21.

- ^ a b Kolb 2019, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Tindale 2007, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Hansen 2019, 1. The core fallacies.

- ^ Walton 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Wrisley 2019, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Merriam-Webster 2019, note1.

- ^ Walton 2001.

- ^ Weston 2018, p. 82.

- ^ Walton 2006, p. 122.

- ^ Orkibi 2018, pp. 497–498.

- ^ Walton 2008, p. 170.

- ^ Taylor 1995, pp. 34–60.

Sources

[edit]- Bowell, Tracy; Kemp, Gary (2010). Critical Thinking: A Concise Guide. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47183-1.

- Copi, Irving M. (1986). Informal Logic. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-324940-2.

- Hansen, Hans (2019). "Fallacies". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Kolb, Leigh (2019). "Guilt by Association". In Robert Arp; Steven Barbone; Michael Bruce (eds.). Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 351–353. doi:10.1002/9781119165811.ch83. ISBN 978-1-119-16580-4. S2CID 187211421.

- Lavery, Jonathan; Hughes, Willam (27 May 2008). Critical Thinking, fifth edition: An Introduction to the Basic Skills. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-77048-111-4.

- Lewis, Charlton; Short, Charles (1879). A Latin Dictionary. Nigel Gourlay. ISBN 9781999855789.

- Merriam-Webster (2019). "Definition of Ad Hominem". Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- Nuchelmans, Gäbriel (1993). "On the Fourfold Root of the Argumentum ad Hominem". In Krabbe, Erik C. W.; Dalitz, Renée José; Smit, Pier (eds.). Empirical Logic and Public Debate.

- Olivesi, Aurélie (2010-04-05). "L'interrogation sur la compétence politique en 2007 : une question de genre ?". Quaderni (in French) (72): 59–74. doi:10.4000/quaderni.486. ISSN 0987-1381.

- Orkibi, Eithan (2018-02-27). "Precedential Ad Hominem in Polemical Exchange: Examples from the Israeli Political Debate". Argumentation. 32 (4): 485–499. doi:10.1007/s10503-018-9453-2. ISSN 0920-427X. S2CID 254261480.

- Sommers, Christina (March 1991). "Argumentum ad feminam". Journal of Social Philosophy. 22 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9833.1991.tb00016.x. ISSN 0047-2786.

- Taylor, Charles (1995). "Explanation and Practical Reason". Philosophical Arguments. Harvard University Press. pp. 34–60. ISBN 9780674664760.

- Tindale, Christopher W. (22 January 2007). Fallacies and Argument Appraisal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46184-9.

- van Eemeren, F. H. (2001). Crucial Concepts in Argumentation Theory. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-523-0.

- van Eemeren, Frans H.; Grootendorst, Rob (2015). "The History of the Argumentum Ad Hominem Since the Seventeenth Century". Argumentation Library. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20955-5_32. ISBN 978-3-319-20954-8. ISSN 1566-7650.

- Walton, Douglas N. (1998). Ad Hominem Arguments. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0922-0.

- Walton, Douglas N. (2001). "Argumentation Schemes and Historical Origins of the Circumstantial Ad Hominem Argument" (PDF). Argumentation. 15 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1023/A:1011120100277. ISSN 0920-427X. S2CID 16864574.

- Walton, Douglas N. (2006). Fundamentals of Critical Argumentation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82319-7.

- Walton, Douglas N. (2008). Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Walton, Douglas N. (27 April 2015). "informal logic". In Audi Robert (ed.). The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01505-0.

- Weston, Anthony (2018). A Rulebook for Arguments. Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-62466-655-1.

- Wong, Andrew David (2017). Unmitigated Skepticism: The Nature and Scope of Pyrrhonism (PDF) (Thesis). University of California.

- Wrisley, George (2019). "Ad Hominem: Circumstantial". In Robert Arp; Steven Barbone; Michael Bruce (eds.). Bad Arguments: 100 of the Most Important Fallacies in Western Philosophy. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 77–82. doi:10.1002/9781119165811.ch9. ISBN 978-1-119-16580-4. S2CID 171674012.

External links

[edit]- Ad hominem at PhilPapers

- Argumentum Ad Hominem

- Ad hominem at Fallacy Check, with examples