Montreal Metro: Difference between revisions

| (236 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | |||

{{about|the subway system}} |

{{about|the subway system}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Use Canadian English|date=October 2016}} |

{{Use Canadian English|date=October 2016}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date= |

{{Use mdy dates|date=June 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox public transit |

{{Infobox public transit |

||

| name = Montreal Metro |

| name = Montreal Metro |

||

| image = |

| image = Montreal public transit icons - Métro.svg |

||

| imagesize = 100px |

| imagesize = 100px |

||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| image2 = MontrealMetroMosaic.jpg |

| image2 = MontrealMetroMosaic.jpg |

||

| imagesize2 = 300px |

| imagesize2 = 300px |

||

| caption2 = Left to right, from top: [[Hector Guimard]]'s [[Paris Métro]] entrance at {{stms|Square- |

| caption2 = Left to right, from top: [[Hector Guimard]]'s [[Paris Métro]] entrance at {{stms|Square-Victoria–OACI}}; interior of the new [[MPM-10]] ("Azur") trains;<ref>{{cite news|title=Bombardier to lay off 145 workers in La Pocatière over Metro car production stall|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/bombardier-to-lay-off-145-workers-in-la-pocati%C3%A8re-over-metro-car-production-stall-1.2929926|access-date=April 4, 2015|work=CBC News|date=January 23, 2015}}</ref> MR-73 train at {{stms|Montmorency}} station; two MR-73 trains at {{stms|Plamondon}} station; ceramic mural at {{stms|Crémazie}} station |

||

| native_name = |

| native_name = {{native name|fr|Métro de Montréal}} |

||

| owner = |

| owner = |

||

| area served = |

| area served = |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

| start = |

| start = |

||

| end = |

| end = |

||

| stations = 68 |

| stations = 68 (5 under construction) |

||

| ridership = {{American transit ridership|QC Montreal HR daily}} ({{American transit ridership|dailydate}}){{American transit ridership|dailycitation}} |

|||

| annual_ridership = 383,147,700 (2018)<ref name="APTA-2018">{{cite web |url=https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2018-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf |title=APTA Q4 2018 Ridership Report |publisher=American Public Transportation Association |pages=36 |date=April 12, 2019 |access-date=April 12, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190508212304/https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2018-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf |archive-date=May 8, 2019 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

| annual_ridership = {{American transit ridership|QC Montreal HR annual}} ({{American transit ridership|annualdate}}){{American transit ridership|annualcitation}} |

|||

| chief_executive = |

| chief_executive = |

||

| website = |

| website = |

||

| began_operation = |

| began_operation = {{Start date and age|1966|10|14}} |

||

| operator = [[Société de transport de Montréal]] |

| operator = [[Société de transport de Montréal]] |

||

| character = |

| character = Fully underground |

||

| vehicles = 909<ref>http://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/pi_20-29.pdf#page71</ref> |

| vehicles = 909<ref>{{Cite web |date=October 29, 2019 |title=Programme des immobilisations 2020-2029 |url=http://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/pi_20-29.pdf#page71 |access-date=June 20, 2022 |website=Société de transport de Montréal |page=71 |language=fr}}</ref> |

||

| train_length = |

| train_length = |

||

| headway = |

| headway = |

||

| system_length = {{convert|69.2|km|mi|abbr=on}}<ref name="urbanrail">[http://www.urbanrail.net/am/monr/montreal.htm Montreal Metro] at urbanrail.net</ref><ref name="metrobits">[http://mic-ro.com/metro/metrocity.html?city=Montreal Montreal Metro] at metrobits.org</ref> |

| system_length = {{convert|69.2|km|mi|abbr=on}}<ref name="urbanrail">[http://www.urbanrail.net/am/monr/montreal.htm Montreal Metro] at urbanrail.net</ref><ref name="metrobits">[http://mic-ro.com/metro/metrocity.html?city=Montreal Montreal Metro] at metrobits.org</ref> |

||

| track_gauge = {{Track gauge|sg| |

| track_gauge = {{Track gauge|sg|lk=on}} with [[running pad]]s for the [[Rubber-tyred metro|rubber tired wheels]] outside of the [[Rail profile|steel rails]] |

||

| el = |

| el = {{750 V DC|conductor=guide bar}} |

||

| |

| top_speed = {{convert|72.4|km/h|mph|abbr=on}} |

||

| |

| map = {{Montreal Metro|inline=y}} |

||

| |

| map_state = collapsed |

||

| map_state = |

|||

| ridership = 1,421,200 (avg. weekday, Q4 2019)<ref name="APTA-2019">https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2019-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf</ref> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The '''Montreal Metro''' ({{langx|fr|Métro de Montréal}}, {{IPA|fr|metʁo də mɔ̃ʁeal|pron}}) is a [[Rubber-tyred metro|rubber-tired]] underground [[rapid transit]] system serving [[Greater Montreal]], Quebec, Canada. The metro, operated by the [[Société de transport de Montréal]] (STM), was inaugurated on October 14, 1966, during the tenure of Mayor [[Jean Drapeau]]. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | It has expanded since its opening from 22 stations on two lines to 68 stations on four lines totalling {{convert|69.2|km|mi}} in length,<ref name="urbanrail"/><ref name="metrobits"/> serving the north, east and centre of the [[Island of Montreal]] with connections to [[Longueuil]], via the [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|Yellow Line]], and [[Laval, Quebec|Laval]], via the [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange Line]]. |

||

| ⚫ | The Montreal Metro is Canada's |

||

| ⚫ | The Montreal Metro is Canada's busiest rapid transit system in terms of daily ridership, delivering an average of {{American transit ridership|QC Montreal HR daily}} daily unlinked passenger trips per weekday as of {{American transit ridership|dailydateasof}}.<ref name="APTA-2022">{{cite web |url=https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf |title=APTA Q4 2022 Ridership Report |publisher=American Public Transportation Association |pages=39 |date=March 1, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190508212304/https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf |archive-date=May 8, 2019 |url-status=live }}</ref> It is [[List of North American rapid transit systems by ridership|North America's third busiest]] rapid transit system, behind the [[New York City Subway]] and [[Mexico City Metro]]. In {{American transit ridership|annualdate}}, {{American transit ridership|QC Montreal HR annual}} trips on the Metro were completed.<ref name="APTA-2022"/> With the Metro and the newer driverless, steel-wheeled [[Réseau express métropolitain]], Montreal has one of North America's largest urban rapid transit systems, attracting the second-highest ridership per capita behind [[New York City]].<ref>{{cite web|author=Yonah Freemark |url=http://www.thetransportpolitic.com/2009/09/18/montreal-and-quebec-leaders-announce-irreversible-decision-to-expand-metro/ |title=Montréal and Québec Leaders Announce "Irreversible" Decision to Expand Métro – The Transport Politic |publisher=Thetransportpolitic.com |date=September 18, 2009 |access-date=March 10, 2011}}</ref> |

||

The Montreal Metro was inspired by the [[Paris Métro]], which is clearly seen in the Metro's station design and rolling stock.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.virgin-vacations.com/11-top-underground-transit-systems-in-the-world.aspx |title=Archived copy |access-date=February 16, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100213134525/http://www.virgin-vacations.com/11-top-underground-transit-systems-in-the-world.aspx |archive-date=February 13, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

[[File:St.JamesSt.-Montreal -1910.jpg|thumb|St. James/Saint-Jacques St. Streetcars in 1910]] |

[[File:St.JamesSt.-Montreal -1910.jpg|thumb|St. James/Saint-Jacques St. Streetcars in 1910]] |

||

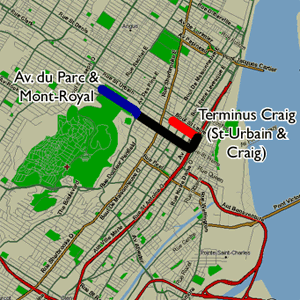

Urban transit began in [[Montreal]] in 1861 when a line of [[Horsecar|horse-drawn cars]] started to operate on Craig (now [[Saint Antoine Street|St-Antoine]]) and [[Notre-Dame Street|Notre-Dame]] streets. Eventually, as the |

Urban transit began in [[Montreal]] in 1861 when a line of [[Horsecar|horse-drawn cars]] started to operate on Craig (now [[Saint Antoine Street|St-Antoine]]) and [[Notre-Dame Street|Notre-Dame]] streets. Eventually, as the city grew, a comprehensive network of [[Streetcars in Montreal|streetcar]] lines provided service in most of the city. But urban congestion started to take its toll on streetcar punctuality, so the idea of an underground system was soon considered.<ref name="Clairoux2001_p112">{{harvsp|Clairoux|2001|p=11}}.</ref> |

||

=== Fifty years of projects === |

=== Fifty years of projects === |

||

In 1902, as European and American cities were inaugurating their first [[Rapid transit|subway systems]], the [[Government of Canada|federal government]] created the Montreal Subway Company to promote the idea in Canada. |

In 1902, as European and American cities were inaugurating their first [[Rapid transit|subway systems]], the [[Government of Canada|Canadian federal government]] created the Montreal Subway Company to promote the idea in Canada. |

||

Starting in 1910, many proposals were tabled but the Montreal Metro would prove to be an elusive goal. |

Starting in 1910, many proposals were tabled but the Montreal Metro would prove to be an elusive goal. The [[Montreal Street Railway Company]], the Montreal Central Terminal Company and the Montreal Underground and Elevated Railway Company all undertook fruitless negotiations with the city.<ref name="Clairoux2001_p112"/> A year later, the Comptoir Financier Franco-Canadien and the Montreal Tunnel Company proposed tunnels under the city centre and the [[Saint Lawrence River|Saint-Lawrence River]] to link the emerging [[South Shore (Montreal)|South Shore]] neighbourhoods but faced the opposition of railway companies.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.genealogieplanete.com/user/blogs/view/name_lisejolin/id_2861/title_Le-M-tro-de-Montr-al-les-projets-1902-1953/|title=Le Metro de Montreal : les projets 1902–1953|website=www.genealogieplanete.com|language=fr|access-date=October 24, 2016}}</ref> The [[Montreal Tramways Company]] (MTC) was the first to receive the approval of the provincial government in 1913 and four years to start construction.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/about/discover_the_stm_its_history/history/company-timeline|title=Company timeline|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 24, 2016}}</ref> The reluctance of elected city officials to advance funds foiled this first attempt. |

||

The issue of a subway remained present in the newspapers but [[World War I]] and the following recession |

The issue of a subway remained present in the newspapers but [[World War I]] and the following recession prevented any execution. The gradual return to financial health during the 1920s brought the MTC project back and attracted support from the [[premier of Quebec]].<ref name="Clairoux2001_p112" /> This new attempt was stalled by the [[Great Depression]], which saw the city's streetcar ridership atrophy. A subway proposal was next made by Mayor [[Camillien Houde]] in 1939 as a way to provide work for the jobless masses.<ref name=":0">{{Cite news|url=http://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/montreal-metro/|title=Montréal Metro|last=Gilbert|first=Dale|newspaper=The Canadian Encyclopedia|access-date=October 24, 2016}}</ref> |

||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="200"> |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="200"> |

||

| Line 65: | Line 63: | ||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

[[World War II]] and the [[Home front during World War II#Canada|war effort]] in [[Montreal]] resurrected |

[[World War II]] and the [[Home front during World War II#Canada|war effort]] in [[Montreal]] resurrected the idea of a metro. In 1944, the MTC proposed a two-line network, with one line running underneath [[Saint Catherine Street]] and the other under [[Saint Denis Street|Saint Denis]], [[Notre-Dame Street|Notre-Dame]] and [[Saint Jacques Street|Saint Jacques]] Streets.<ref>{{harvsp|Clairoux|2001|p=13}}.</ref> In 1953, the newly formed public Montreal Transportation Commission replaced streetcars with buses and proposed a single subway line reusing the 1944 plans and extending it all the way to [[Quebec Autoroute 40|Boulevard Crémazie]], right by the [[#Plateau d'Youville|D'Youville maintenance shops]].<ref name=":1">{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/about/discover_the_stm_its_history/history/50-years-metro-history|title=Métro history|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 25, 2016}}</ref> By this point, construction was already well underway on [[Toronto subway and RT|Canada's first subway line]] in [[Toronto]] under [[Yonge Street]], which would open in 1954. Still, Montreal councillors remained cautious and no work was initiated. For some of them, including [[Jean Drapeau]] during his first municipal term, public transit was a thing of the past.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

In 1959, a private company, the Société d'expansion métropolitaine, offered to build a [[rubber-tyred metro|rubber-tired metro]] but the Transportation Commission wanted its own network and rejected the offer.<ref>{{harvsp|Clairoux|2001|p=21}}.</ref> This |

In 1959, a private company, the Société d'expansion métropolitaine, offered to build a [[rubber-tyred metro|rubber-tired metro]] but the Transportation Commission wanted its own network and rejected the offer.<ref>{{harvsp|Clairoux|2001|p=21}}.</ref> This would be the last missed opportunity, for the re-election of [[Jean Drapeau]] as mayor and the arrival of his right-hand man, [[Lucien Saulnier]], would prove decisive. In the early [[1960 in Canada|1960s]], the [[Western world]] experienced an economic boom and [[Quebec]] underwent its [[Quiet Revolution]]. From August 1, 1960, many municipal services reviewed the project and on November 3, 1961, the Montreal City Council voted appropriations amounting to $132 million ($1.06 billion in 2016) to construct and equip an initial network {{convert|16|km}} in length.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

=== |

=== Construction === |

||

The 1961 plan reused several previous studies and planned three lines carved into the rock under the city centre to the most populated areas of the city. The City of Montreal (and its chief engineer [[Lucien L'Allier]]) were assisted in the detailed design and engineering of the Metro by French consultant [[SOFRETU]], owned by the operator of the [[Paris Métro]].<ref>{{Cite news |date=February 9, 1982 |title=LES PROJETS DE LA SOFRETU |language=fr |work=Le Monde.fr |url=https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1982/02/09/les-projets-de-la-sofretu_2886786_1819218.html |access-date=August 21, 2023}}</ref> The French influence is clearly seen in the station design and rolling stock of the Metro.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.virgin-vacations.com/11-top-underground-transit-systems-in-the-world.aspx |title=Top 11 Underground Transit Systems Throughout the World |access-date=February 16, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100213134525/http://www.virgin-vacations.com/11-top-underground-transit-systems-in-the-world.aspx |archive-date=February 13, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> [[Rubber-tyred metro|Rubber tires]] were chosen instead of steel ones, following the Parisian influence - as the rubber tired trains could use steeper grades and accelerate faster.<ref name=":8">{{Cite news |last=Magder |first=Jason |date=October 13, 2016 |title=The métro at 50: Building the network |work=[[Montreal Gazette]] |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/the-metro-at-50-building-the-network}}</ref> 80% of the tunnels were built through rock, as opposed to the traditional [[cut-and-cover]] method used for the construction of the [[Yonge Subway]] in Toronto.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

The 1961 plan reused several previous studies and planned three lines carved into the rock under the city centre to the most populated areas of the city. |

|||

=== The first two lines === |

|||

[[File:Plaque commemorative, station Berri-UQAM.JPG|thumb|left|[[Berri–UQAM station]] tablet]] |

[[File:Plaque commemorative, station Berri-UQAM.JPG|thumb|left|[[Berri–UQAM station]] tablet]] |

||

The main line, or Line 1 ([[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|Green Line]]) was to pass between the two most important arteries, [[Saint Catherine Street|Saint Catherine]] and [[Sherbrooke Street|Sherbrooke]] streets, more or less under the [[De Maisonneuve Boulevard]]. It would extend between the English-speaking west at [[Atwater station]] and French-speaking east at {{stms|Frontenac}}. Line 2 ([[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange Line]]) was to run from north of the downtown, from [[Crémazie station]] through various residential neighbourhoods to the business district at [[Place-d'Armes station]]. |

The main line, or Line 1 ([[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|Green Line]]) was to pass between the two most important arteries, [[Saint Catherine Street|Saint Catherine]] and [[Sherbrooke Street|Sherbrooke]] streets, more or less under the [[De Maisonneuve Boulevard]]. It would extend between the English-speaking west at [[Atwater station]] and French-speaking east at {{stms|Frontenac}}. Line 2 ([[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange Line]]) was to run from north of the downtown, from [[Crémazie station]] through various residential neighbourhoods to the business district at [[Place-d'Armes station]]. |

||

Construction of the first two lines began May 23, 1962 under the supervision of the Director of Public Works, |

Construction of the first two lines began May 23, 1962,<ref>{{Cite web |title=The métro at 50: A métro by Montrealers, for Montrealers |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreals-rubber-tired-metro-turns-50 |access-date=May 6, 2022 |website=montrealgazette |language=en-CA}}</ref> under the supervision of the Director of Public Works, Lucien L'Allier. On June 11, 1963, the construction costs for tunnels being lower than expected, Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] was extended by two stations at each end and the new termini became the {{stms|Henri-Bourassa}} and {{stms|Bonaventure}} stations.<ref name=":8" /> The project, which employed more than 5,000 workers at its height, and cost the lives of 12 of them, ended on October 14, 1966. The service was opened gradually between October 1966 and April 1967 as the stations were completed. |

||

==== Cancellation of Line 3==== |

==== Cancellation of Line 3==== |

||

[[File:1961-MetroMontreal.png|right|thumb|1961 project, showing the third line]] |

[[File:1961-MetroMontreal.png|right|thumb|1961 project, showing the third line]] |

||

A third line was planned. It was to use [[Canadian National Railway]] (CN) tracks passing under the [[Mount Royal Tunnel|Mount Royal]] to reach the northwest suburb of [[Cartierville]] from the city centre. Unlike the previous two lines, trains were to be partly running above ground. Negotiations with the CN and municipalities were stalling as [[Montreal]] was chosen in November 1962 to hold the [[World's fair|1967 Universal Exposition]] ([[Expo 67]]). Having to make a choice, the city decided that a number 4 line |

A third line was planned. It was to use [[Canadian National Railway]] (CN) tracks passing under the [[Mount Royal Tunnel|Mount Royal]] to reach the northwest suburb of [[Cartierville]] from the city centre. Unlike the previous two lines, trains were to be partly running above ground. Negotiations with the CN and municipalities were stalling as [[Montreal]] was chosen in November 1962 to hold the [[World's fair|1967 Universal Exposition]] ([[Expo 67]]). Having to make a choice, the city decided that a number 4 line [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] linking [[Montreal]] to the [[South Shore (Montreal)|South Shore]] suburbs following a plan similar to those proposed early in the 20th century was more necessary.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title=Le métro de Montréal|last=Bureau de transport métropolitain|publisher=Bureau de transport métropolitain|year=1983|isbn=2-920295-19-5|location=Bibliothèque nationale du Québec|language=fr}}</ref> |

||

Line 3 was never built and the number was never used again. The railway, already used for a [[Deux-Montagnes line|commuter train]] to the [[North Shore (Montreal)|North Shore]] at [[Deux-Montagnes, Quebec|Deux-Montagnes]], was completely renovated in the early [[1990 in Canada|1990s]] and effectively replaced the planned third line. The next line would thus be numbered 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. Subsequently, elements of the line, particularly the Deux-Montagnes commuter train, became the first line of the [[Réseau express métropolitain|Réseau Express Métropolitain]]. |

Line 3 was never built and the number was never used again. The railway, already used for a [[Deux-Montagnes line|commuter train]] to the [[North Shore (Montreal)|North Shore]] at [[Deux-Montagnes, Quebec|Deux-Montagnes]], was completely renovated in the early [[1990 in Canada|1990s]] and effectively replaced the planned third line. The next line would thus be numbered 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. Subsequently, elements of the line, particularly the Deux-Montagnes commuter train, became the first line of the [[Réseau express métropolitain|Réseau Express Métropolitain]]. |

||

==== Expo 67 ==== |

==== Expo 67 ==== |

||

The Montreal municipal administration asked municipalities of the [[South Shore (Montreal)|South Shore]] of the [[Saint Lawrence River]] which one would be interested in the Metro and [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]] got the link. Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] would therefore pass under the river, from [[Berri–UQAM station|Berri-de-Montigny station]], junction of Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] and Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]], to [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]]. A stop was added in between to access the site of Expo 67, built on two islands of the [[Hochelaga Archipelago]] in the river. [[Saint Helen's Island]], on which the station of the same name was built, was massively enlarged and consolidated with several nearby islands (including Ronde Island) using backfill excavated during the construction of the Metro. [[Notre Dame Island]], adjacent, was created from scratch with the same material. Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] was completed on April 1, 1967, in time for the opening of the World's Fair.<ref name=":2" /> |

The Montreal municipal administration asked municipalities of the [[South Shore (Montreal)|South Shore]] of the [[Saint Lawrence River]] which one would be interested in the Metro and [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]] got the link. Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] would therefore pass under the river, from [[Berri–UQAM station|Berri-de-Montigny station]], junction of Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] and Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]], to [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]].<ref name=":8" /> A stop was added in between to access the site of Expo 67, built on two islands of the [[Hochelaga Archipelago]] in the river. [[Saint Helen's Island]], on which the station of the same name was built, was massively enlarged and consolidated with several nearby islands (including Ronde Island) using backfill excavated during the construction of the Metro. [[Notre Dame Island]], adjacent, was created from scratch with the same material. Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] was completed on April 1, 1967, in time for the opening of the World's Fair.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

The first Metro network was completed with the public opening of Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] on April 28, 1967. The cities of [[Montreal]], [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]] and [[Westmount, Quebec|Westmount]] had assumed the entire cost of construction and equipment of $213.7 million ($1.6 billion in 2016). [[Montreal]] became the seventh city in North America to operate a subway. The 1960s being very optimistic years, Metro planning did not escape the general exuberance of the time, and a 1967 study |

The first Metro network was completed with the public opening of Line 4 [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|(Yellow Line)]] on April 28, 1967. The cities of [[Montreal]], [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]] and [[Westmount, Quebec|Westmount]] had assumed the entire cost of construction and equipment of $213.7 million ($1.6 billion in 2016). [[Montreal]] became the seventh city in North America to operate a subway. The 1960s being very optimistic years, Metro planning did not escape the general exuberance of the time, and a 1967 study, "Horizon 2000",<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://archivesdemontreal.com/2011/10/07/le-film-horizon-2000-devoile-en-1967/|title=Le film Horizon 2000 dévoilé en 1967 !|website=archivesdemontreal.com|publisher=Archives de Montréal|language=fr|access-date=October 26, 2016}}</ref> imagined a network of {{convert|160|km}} of tunnels for the year 2000.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://emdx.org/rail/metro/futur.php|title=Le futur n'était-il pas magnifique?|website=emdx.org|access-date=October 26, 2016}}</ref> |

||

=== Extensions and unbuilt lines === |

=== Extensions and unbuilt lines === |

||

| Line 94: | Line 92: | ||

==== Montreal Olympics ==== |

==== Montreal Olympics ==== |

||

The success of the Metro increased the pressure to extend the network to other populated areas, including the suburbs on the [[Island of Montreal]]. After being awarded, in May 1970, the [[1976 Summer Olympics]], a loan of $430 million ($2.7 billion in 2016) was approved by the MUC on February 12, 1971 to fund the extensions of Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] and Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] and the construction of a transverse line: Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. The [[Government of Quebec]] agreed to bear 60% of the costs. |

The success of the Metro increased the pressure to extend the network to other populated areas, including the suburbs on the [[Island of Montreal]]. After being awarded, in May 1970, the [[1976 Summer Olympics]], a loan of $430 million ($2.7 billion in 2016) was approved by the MUC on February 12, 1971, to fund the extensions of Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] and Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] and the construction of a transverse line: Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. The [[Government of Quebec]] agreed to bear 60% of the costs. |

||

The work on the extensions started October 14, 1971 with Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] towards the east to reach the site where the [[Olympic Stadium (Montreal)|Olympic Stadium]] was to be built and [[Quebec Autoroute 25|Autoroute 25]] ({{stms|Honoré-Beaugrand}} station) that could serve as a transfer point for visitors arriving from outside. The extensions were an opportunity to make improvements to the network, such as new trains, larger stations and even semi-automatic control. The first extension was completed in June 1976 just before the Olympics. Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] |

The work on the extensions started October 14, 1971, with Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] towards the east to reach the site where the [[Olympic Stadium (Montreal)|Olympic Stadium]] was to be built and [[Quebec Autoroute 25|Autoroute 25]] ({{stms|Honoré-Beaugrand}} station) that could serve as a transfer point for visitors arriving from outside. The extensions were an opportunity to make improvements to the network, such as new trains, larger stations and even semi-automatic control. The first extension was completed in June 1976 just before the Olympics. Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]] was later extended to the southwest to reach the suburbs of [[Verdun, Quebec|Verdun]] and [[LaSalle, Quebec|LaSalle]] with the {{stms|Angrignon}} as the terminus station, named after the park and zoo. This segment opened at September 1978. |

||

[[File:WTMTL T35 P1130349.JPG|thumb|{{stms|Radisson}} station on Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]]]] |

[[File:WTMTL T35 P1130349.JPG|thumb|{{stms|Radisson}} station on Line 1 [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|(Green Line)]]]] |

||

In the process, further extensions were planned and in 1975 spending was expected to reach reached $1.6 billion ($7.3 billion in 2016). Faced with these soaring costs, the Government of Quebec declared a moratorium May 19, 1976 to the all-out expansion desired by Mayor [[Jean Drapeau]]. Tenders were frozen, including those of Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] after the {{stms|Snowdon}} station and those of Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] whose works were yet already underway. A struggle then ensued between the MUC and the Government of Quebec as any extension could not be done without the agreement of both parties. The Montreal Transportation Office |

In the process, further extensions were planned and in 1975 spending was expected to reach reached $1.6 billion ($7.3 billion in 2016). Faced with these soaring costs, the Government of Quebec declared a moratorium May 19, 1976, to the all-out expansion desired by Mayor [[Jean Drapeau]]. Tenders were frozen, including those of Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] after the {{stms|Snowdon}} station and those of Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] whose works were yet already underway. A struggle then ensued between the MUC and the Government of Quebec as any extension could not be done without the agreement of both parties. The Montreal Transportation Office might have tried to put the government in front of a ''fait accompli'' by awarding large contracts to build the tunnel between {{stms|Namur}} station and the [[Bois-Franc (AMT)|Bois-Franc]] station just before the moratorium was in force.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://esteemfoundation.org/emdx//rail/metro/expansion.php|title=Expansion du réseau|website=esteemfoundation.org|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

||

==== Moratorium on |

==== Moratorium on expansion ==== |

||

[[File:Métro Acadie.jpg|thumb|{{stms|Acadie}} station on Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]]] |

[[File:Métro Acadie.jpg|thumb|{{stms|Acadie}} station on Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]]] |

||

In 1977, the newly elected government partially lifted the moratorium on the extension of Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] and the construction of Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. |

In 1977, the newly elected government partially lifted the moratorium on the extension of Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] and the construction of Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]]. In 1978, the STCUM proposed a map which includes a western extension of Line 5 (Blue Line) that includes stations in N.D.G., Montreal West, Ville St. Pierre, Lachine, LaSalle, and potentially beyond. |

||

Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] was gradually extended westward to {{stms|Place-Saint-Henri}} station in 1980 and to {{stms|Snowdon}} station in 1981. As the stations were completed, the service was extended. In December 1979 Quebec presented its "integrated transport plan" in which Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] was to be tunnelled to [[Du Collège station]] and Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] from {{stms|Snowdon}} station to [[Anjou, Quebec|Anjou]] station. The plan proposed no other underground lines as the government preferred the option of converting existing railway lines to overground Metro ones. The mayors of the MUC, initially reluctant, accepted this plan when |

Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] was gradually extended westward to {{stms|Place-Saint-Henri}} station in 1980 and to {{stms|Snowdon}} station in 1981. As the stations were completed, the service was extended. In December 1979 Quebec presented its "integrated transport plan" in which Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] was to be tunnelled to [[Du Collège station]] and Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] from {{stms|Snowdon}} station to [[Anjou, Quebec|Anjou]] station. The plan proposed no other underground lines as the government preferred the option of converting existing railway lines to overground Metro ones. The mayors of the MUC, initially reluctant, accepted this plan when Quebec promised in February 1981 to finance future extensions fully. The moratorium was then modestly lifted on Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] that reached [[Du Collège station]] in 1984 and finally {{stms|Côte-Vertu}} station in 1986. This line took the shape of an "U" linking the north of the island to the city centre and serving two very populous axes. |

||

The various moratoriums and technical difficulties encountered during the construction of the fourth line stretched |

The various moratoriums and technical difficulties encountered during the construction of the fourth line stretched the project over fourteen years. Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]], which runs through the centre of the [[island of Montreal]], crossed the east branch of Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] at the {{stms|Jean-Talon}} station in 1986 and its west branch at the [[Snowdon (Montreal Metro)|Snowdon)]] station in 1988. Because it was not crowded, the STCUM at first operated Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] weekdays only from 5:30 am to 7:30 pm and was circulating only three-car trains instead of the nine car trains in use along the other lines. Students from the [[Université de Montréal|University of Montreal]], the main source of customers, obtained extension of the closing time to 11:10 pm and then 0:15 am in 2002.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.metrodemontreal.com/blue/index.html|title=Line 5 – Blue|website=www.metrodemontreal.com|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

||

==== Recession and unfinished projects ==== |

==== Recession and unfinished projects ==== |

||

[[File:Metro montreal geographical map 1984.png|thumb|Metro lines and MUC proposed expansions in 1984]] |

[[File:Metro montreal geographical map 1984.png|thumb|Metro lines and MUC proposed expansions in 1984]] |

||

In the late 1980s, the original network length had nearly quadrupled in twenty years and exceeded that of Toronto, but the plans did not stop there. In its 1983–1984 scenario, the MUC planned a new underground Metro Line 7 [[White Line (Montreal Metro)|(White Line)]] ({{stms|Pie-IX}} station |

In the late 1980s, the original network length had nearly quadrupled in twenty years and exceeded that of Toronto, but the plans did not stop there. In its 1983–1984 scenario, the MUC planned a new underground Metro Line 7 [[White Line (Montreal Metro)|(White Line)]] ({{stms|Pie-IX}} station to [[Montréal-Nord]]) and several surface lines numbered [[Line 6 (Montreal Metro)|Line 6]] ([[Du Collège (Montreal Metro)|Du College]] station to [[Repentigny, Quebec|Repentigny]]), Line 8 ({{stms|Radisson}} station to [[Pointe-aux-Trembles]]), Line 10 ([[Vendôme (Montreal Metro)|Vendome]] station to [[Lachine, Quebec|Lachine]]) and Line 11 ({{stms|Angrignon}} terminus to [[LaSalle, Quebec|LaSalle]]). In 1985, a new government in Quebec rejected the project, replacing the Metro lines by commuter train lines in its own 1988 transport plan. Yet the provincial elections of 1989 approaching, the Line 7 [[White Line (Montreal Metro)|(White Line)]] project reappeared and the extensions of Line 5 [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|(Blue Line)]] to [[Anjou, Quebec|Anjou]] (''Pie-IX'', ''Viau'', ''Lacordaire'', ''Langelier'' and ''Galeries d'Anjou'') and Line 2 [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|(Orange Line)]] northward (''Deguire''/''Poirier'', ''Bois-Franc'' and ''Salaberry'') were announced. |

||

At the beginning of the 1990s, there was a significant deficit in public finances across |

At the beginning of the 1990s, there was a significant deficit in public finances across Canada, especially in Quebec, and an economic recession. Metro ridership decreased and the Government of Quebec removed subsidies for the operation of urban public transport.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/montreal/339029/achalandage-record-pour-le-transport-en-commun|title=Achalandage record pour le transport en commun|newspaper=Le Devoir|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> Faced with this situation, the extensions projects were put on hold and the MUC prioritized the renovation of its infrastructures. |

||

=== Creation of AMT, RTM, ARTM, and improvements === |

=== Creation of AMT, RTM, ARTM, and improvements === |

||

In 1996, the Government of Quebec created a supra-municipal agency, the ''Agence métropolitaine de transport'' (AMT), whose mandate is to coordinate the development of transport throughout the [[Greater Montreal]] area. The AMT was responsible, among others, for the development of the Metro and suburban trains. |

In 1996, the Government of Quebec created a supra-municipal agency, the ''Agence métropolitaine de transport'' (AMT), whose mandate is to coordinate the development of transport throughout the [[Greater Montreal]] area. The AMT was responsible, among others, for the development of the Metro and suburban trains. |

||

On June 1, 2017, the AMT was disbanded and replaced by two distinct agencies by the Loi 76 (English: |

On June 1, 2017, the AMT was disbanded and replaced by two distinct agencies by the Loi 76 (English: Law 76), the [[Autorité régionale de transport métropolitain]] (ARTM), mandated to manage and integrate road transport and public transportation in Greater Montreal; and the [[Réseau de transport métropolitain]] (RTM, publicly known as exo), which took over all operations from the former Agence métropolitaine de transport. RTM now operates Montreal's commuter rail and metropolitan bus services, and is the second busiest such system in Canada after [[Toronto]]'s [[GO Transit]]. |

||

==== Laval extension ==== |

==== Laval extension ==== |

||

| Line 124: | Line 122: | ||

==== Major renovations ==== |

==== Major renovations ==== |

||

Since 2004, most of the [[Société de transport de Montréal|STM's]] investments have been directed to rolling stock and infrastructure renovation programs.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/fr/a-propos/informations-entreprise-et-financieres/priorisation-des-projets-dinvestissements-2011-2020|title=Priorisation des Projets d'investissements 2011–2020 de 11,5 G$|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> New trains ([[MPM-10]]) |

Since 2004, most of the [[Société de transport de Montréal|STM's]] investments have been directed to rolling stock and infrastructure renovation programs.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/fr/a-propos/informations-entreprise-et-financieres/priorisation-des-projets-dinvestissements-2011-2020|title=Priorisation des Projets d'investissements 2011–2020 de 11,5 G$|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> New trains ([[MPM-10]]) have been delivered, replacing the older [[MR-63]] trains. Tunnels are being repaired and several stations, including {{stms|Berri–UQAM}}, have been several years in rehabilitation. Many electrical<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/service-updates/stm-works/guizot-rectifier-station|title=Guizot rectifier station|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> and ventilation structures<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/service-updates/stm-works/saint-timothee-mechanical-ventilation-station|title=Saint-Timothée mechanical ventilation station|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/service-updates/stm-works/saint-dominique-mechanical-ventilation-station|title=Saint-Dominique mechanical ventilation station|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> on the surface are in 2016 completely rebuilt to modern standards. In 2020, work to install [[cellular coverage]] in the Metro was completed.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Magder |first=Jason |date=December 3, 2020 |title=Cellular coverage now extended throughout Montreal métro network |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/cellular-coverage-now-extended-throughout-montreal-metro-network |access-date=August 29, 2023 |website=Montreal Gazette}}</ref> Station accessibility has also been improved, with over 26 of the 68 stations having elevators installed since 2007.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web |date=April 3, 2023 |title=McGill station becomes 26th accessible station in the métro network |url=https://www.stm.info/en/press/press-releases/2023/mcgill-station-becomes-26th-accessible-station-in-the-metro-network |access-date=April 4, 2023 |website=Société de transport de Montréal |language=en}}</ref> |

||

==== Réseau express métropolitain ==== |

|||

In August 2023, the first phase of the [[Réseau express métropolitain]] (REM) opened between [[Montreal Central Station|Gare Centrale]] and [[Brossard station|Brossard]].<ref name="July31">{{cite news |date=July 7, 2023 |title=Le REM ouvert au public le 31 juillet |newspaper=La Presse |url=https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/grand-montreal/2023-07-07/le-rem-ouvert-au-public-le-31-juillet.php |access-date=July 7, 2023 |lang=fr}}</ref> The system is independent of, but connects to and hence complements, the Metro. Built by [[CDPQ Infra]], part of the Quebec pension fund [[Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec]], the line will eventually run north-south across Montreal, with interchanges with the Metro at Gare Centrale (Bonaventure), McGill and Édouard-Montpetit.<ref>{{Cite web |date=October 10, 2019 |title=Réseau express métropolitain |url=https://www.cdpqinfra.com/en/projects/rem |access-date=August 22, 2023 |website=CDPQ Infra {{!}} Un modèle novateur pour les projets d’infrastructures |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

=== Future growth === |

=== Future growth === |

||

==== |

==== Blue line extension to Anjou ==== |

||

{{Main|Blue_Line_(Montreal_Metro)#Eastern_extension_to_Anjou|l1 = Blue line extension to Anjou}} |

|||

In December 2011, the AMT proposed its "Vision 2020" plan expanding the Line 5 ([[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|Blue]]) towards the borough of [[Anjou, Quebec|Anjou]] and Line 2 ([[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange]]) towards {{exos|Bois-Franc}} train station.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.railwaygazette.com/nc/news/single-view/view/montreacuteals-2020-vision.html |access-date=January 2, 2012|title=Railway Gazette: Montréal's 2020 vision|work=[[Railway Gazette International]]}}</ref> On September 20, 2013 the ''Société de transport de Montréal'' (STM) and provincial government announced the extension of the Line 5 east as far as Anjou with five new stations. After the [[Parti Québécois]] lost the [[2014 Quebec general election|2014 provincial election]], the future of the Blue Line extension came into question. The successor [[Quebec Liberal Party|Liberal]] government had expressed interest in extending mass-transit to the [[Montréal–Trudeau International Airport|Airport]] and implementing a [[light rail]] line on the new [[Champlain Bridge, Montreal|Champlain Bridge]] under construction. The project could cost up to $3 billion based on a February 2016 reassessment.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/montreal/201602/05/01-4947482-prolongement-de-la-ligne-bleue-du-metro-deux-fois-plus-cher-que-prevu.php|title=Prolongement de la ligne bleue du métro: deux fois plus cher que prévu|last=Lessard|first=Denis|newspaper=La Presse|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> Because of funding for infrastructure promised by the federal government in 2015, the Blue Line project remains a priority, according to Quebec and the STM.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://journalmetro.com/local/villeray-st-michel-parc-extension/actualites-villeray-st-michel-parc-extension/932420/canada-investirait-dans-le-prolongement-du-metro-de-montreal/|title=Ottawa investirait dans le prolongement du métro de Montréal|website=Métro|date=March 15, 2016|language=fr-CA|access-date=March 17, 2016}}</ref> In April 2018, the successor Liberal government, along with the Federal government, announced firm plans for the Anjou extension.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Bruemmer |first1=Rene |title=Montreal métro: Green light for Blue Line extension |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreal-metro-green-light-for-blue-line-extension |website=Montreal Gazette |date=April 10, 2018}}</ref> Construction on the Blue Line extension is slated to begin in 2021, with a completion date in 2026.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreal-metro-green-light-for-blue-line-extension |title=Montreal métro: Green light for Blue Line extension |first=René |last=Bruemmer |work=Montreal Gazette |date=9 April 2018 |access-date=4 May 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Following the opening of Line 5 ([[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|Blue]]) in the 1980s, various governments have proposed extending the line east to [[Anjou, Quebec|Anjou]]. In 2013, a proposal to extend the line to Anjou was announced by the STM and the Quebec government.<ref>{{cite web |title=Green light for Montreal métro's Blue Line extension |url=https://montrealgazette.com/a9tro+Blue+Line+extension/8938031/story.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130921210814/http://www.montrealgazette.com/a9tro%2BBlue%2BLine%2Bextension/8938031/story.html |archive-date=September 21, 2013 |access-date=September 21, 2013}}</ref> On April 9, 2018, premier of Quebec [[Philippe Couillard]] and Prime Minister [[Justin Trudeau]] announced their commitment to fund and complete the extension, then planned to open in 2026.<ref name=":32">{{Cite web |last=Bruemmer |first=René |date=April 9, 2018 |title=Montreal métro: Green light for Blue Line extension |url=https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/montreal-metro-green-light-for-blue-line-extension |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=Montreal Gazette |language=en-CA}}</ref> In March 2022, it was announced that the federal government had agreed to provide $1.3 billion to the extension, with further costs to be covered by the provincial government.<ref>{{Cite web |date=July 4, 2019 |title=New investments to extend the Montréal Metro's Blue line |url=https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2019/07/04/new-investments-extend-montreal-metros-blue-line |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=Prime Minister of Canada |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The {{Convert|6|km|adj=on}} extension will include five new stations, two bus terminals, a pedestrian tunnel connecting to the [[Pie-IX BRT]] and a new park-and-ride.<ref name=":13">{{Cite web |title=Blue line extension |url=https://www.stm.info/en/about/major_projects/major-metro-projects/blue-line-extension |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=Société de transport de Montréal |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=March 18, 2022 |title=Montreal Metro's Blue line extension finally a go, but province says it's behind schedule |url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/blue-line-metro-stm-government-funding-1.6389902 |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=CBC News}}</ref> Overall, the project is estimated to cost around $5.8 to $6.4 billion and is scheduled to be completed in 2030.<ref>{{Cite web |date=March 18, 2022 |title=Montreal to get its metro blue line extension in the east end by 2029 |url=https://montreal.citynews.ca/2022/03/18/montreal-metro-blue-line-extension/ |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=montreal.citynews.ca}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/blue-line-metro-extension-stalled-again-due-to-complexity-of-project-1.6578778 | title=Blue line Metro extension stalled again due to complexity of project | date=September 26, 2023 }}</ref> Initial construction work began in August 2022.<ref>{{Cite web |date=August 29, 2022 |title=Aujourd'hui, c'est le jour 1 des travaux du prolongement de la ligne bleue! 🤩🔵 |url=https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=614717083376075&set=a.410626200451832&type=3 |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=Facebook |publisher=[[Projet Montréal]] |language=fr |quote=Aujourd’hui, c’est le jour 1 des travaux du prolongement de la ligne bleue! 🤩🔵 C’est une étape importante pour le développement du transport collectif dans notre métropole. Le nouveau tronçon de la ligne bleue permettra de relier au reste du réseau des quartiers historiquement mal desservis par le métro.}}</ref> |

|||

==== Pink Line ==== |

==== Pink Line ==== |

||

In 2017, [[Valérie Plante]] proposed the [[Pink Line (Montreal Metro)|Pink Line]] as part of her campaign for the office of Mayor of Montreal. The new route would have 29 stations and would primarily northeastern Montreal with the downtown areas, as well as the western end of NDG and Lachine.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/new-metro-line-with-29-stations-would-cost-less-than-6b-projet-montréal-says-1.4348035|title=New Metro line with 29 stations would cost less than $6B, Projet Montréal says |date=October 10, 2017|newspaper=CBC}}</ref> The project has since been added to Quebec's 10-year infrastructure plan, and feasibility studies for the line's western section began in June 2021.<ref>{{cite web | last=Henriquez | first=Gloria | title=Pink line a key campaign promise once again for Projet Montréal - Montreal | website=Global News |date=September 16, 2021 | url=https://globalnews.ca/news/8197453/pink-line-campaign-promise-projet-montreal/ | access-date=November 15, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

In 2017, [[Valérie Plante]] proposed the [[Pink Line (Montreal Metro)|Pink Line]] as part of her campaign for the office of Mayor of Montreal.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/new-metro-line-with-29-stations-would-cost-less-than-6b-projet-montréal-says-1.4348035|title=New Metro line with 29 stations would cost less than $6B, Projet Montréal says |

|||

|date=Oct 10, 2017|newspaper=CBC}}</ref> The new route would have 29 stations and would primarily link northeastern Montreal with the Downtown areas, as well as the western end of NDG and Lachine. Plante was elected Mayor on November 5, 2017. |

|||

== Network == |

== Network == |

||

| Line 145: | Line 146: | ||

The [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|Yellow Line]] is the shortest line, with three stations, built for [[Expo 67]]. Metro lines that leave the [[Île de Montréal]] are the Orange Line, which continues to Laval, and the Yellow Line, which continues to [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]]. |

The [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|Yellow Line]] is the shortest line, with three stations, built for [[Expo 67]]. Metro lines that leave the [[Île de Montréal]] are the Orange Line, which continues to Laval, and the Yellow Line, which continues to [[Longueuil, Quebec|Longueuil]]. |

||

Metro service starts at 05:30, and the last trains start their run between 00:30 and 01:00 on weekdays and Sunday, and between 01:00 and 01:30 on Saturday. During rush hour, there are two to four minutes between trains on the [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange]] and [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|Green Lines]]. The frequency |

Metro service starts at 05:30, and the last trains start their run between 00:30 and 01:00 on weekdays and Sunday, and between 01:00 and 01:30 on Saturday. During rush hour, there are two to four minutes between trains on the [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange]] and [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|Green Lines]]. The frequency decreases to 12 minutes during late nights. |

||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

| Line 152: | Line 153: | ||

! rowspan="2" |From |

! rowspan="2" |From |

||

! rowspan="2" |To |

! rowspan="2" |To |

||

! rowspan="2" |Year |

! rowspan="2" |Year first opened |

||

! rowspan="2" |Year |

! rowspan="2" |Year last extended |

||

! rowspan="2" |Length |

! rowspan="2" |Length |

||

! rowspan="2" |Stations |

! rowspan="2" |Stations |

||

! colspan="3" | |

! colspan="3" |Frequency |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! Rush |

! Rush hour !! Off-peak !! Weekend |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{rint|montreal|metro|1}} || [[Green Line (Montreal Metro)|Green]]|| {{stms|Angrignon}} || {{stms|Honoré-Beaugrand}} || 1966 || 1978 || {{convert|22.1|km|abbr=on}} || 27 || 3–4 minutes || 4–10 minutes || 6–12 minutes |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{rint|montreal|metro|2}} || [[Orange Line (Montreal Metro)|Orange]]|| {{stms|Côte-Vertu}} || {{stms|Montmorency}} |

||

|| 1966 || 2007 || {{convert|30.0|km|abbr=on}} || 31 || 2–4 minutes || 4–10 minutes || 6–12 minutes |

|| 1966 || 2007 || {{convert|30.0|km|abbr=on}} || 31 || 2–4 minutes || 4–10 minutes || 6–12 minutes |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{rint|montreal|metro|4}} || [[Yellow Line (Montreal Metro)|Yellow]]|| {{stms|Berri–UQAM}} || {{stms|Longueuil–Université-de-Sherbrooke}} || 1967 || 1967 || {{convert|3.82|km|abbr=on}} || 3 || 3–5 minutes || 5–10 minutes || 5–10 minutes |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| {{rint|montreal|metro|5}} || [[Blue Line (Montreal Metro)|Blue]]|| {{stms|Snowdon}} || {{stms|Saint-Michel}} || 1986 || 1988 || {{convert|9.53|km|abbr=on}} || 12 || 3–5 minutes || 5–10 minutes || 8–11 minutes |

||

|} |

|} |

||

===Fares=== |

===Fares=== |

||

{{Main| |

{{Main|Opus card}} |

||

{{More citations needed section|date=November 2022}} |

|||

[[File:Turnstiles with OPUS reader at Bonaventure Metro Station in Montreal.jpg|thumb|left| |

[[File:Turnstiles with OPUS reader at Bonaventure Metro Station in Montreal.jpg|thumb|left|Older Opus card and magnetic ticket reader turnstile gate at {{stms|Bonaventure}} station]] |

||

The ''[[Société de transport de Montréal]]'' (STM) operates Metro and bus services in Montreal, and transfers between the two are free inside a 120-minute time frame after the first validation.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/fares/transit-fares/1-trip|title=1 trip|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

The ''[[Société de transport de Montréal]]'' (STM) operates Metro and bus services in Montreal, and transfers between the two are free inside a 120-minute time frame after the first validation.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/fares/transit-fares/1-trip|title=1 trip|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

||

On July 1, 2022, the [[ARTM]] reorganized its fare system into 4 zones: A, B, C, and D. The island of Montreal was placed in zone A and fares for zones B, C and D can be bought separately or together. The Metro fares are fully integrated with the [[Exo (public transit)|Exo commuter rail]] system, which links the metropolitan area to the outer suburbs via six interchange stations ({{stms|Bonaventure}}, {{stms|Lucien-L'Allier}}, {{stms|Vendôme}}, [[De La Concorde station|De la Concorde]], {{stms|Sauvé}}, and [[Park Avenue station (Montreal)|Parc]]) and the [[réseau express métropolitain]] (REM), scheduled to open in the second quarter of 2023. The fares for Exo, the REM and the Metro for zone A are only valid on the island of Montreal. In order to take the Exo, REM or Metro trains from Montreal to Laval (zone B), you must have the corresponding fares for that zone; for example, an all modes AB fare. |

|||

Fare payment is via a barrier system accepting magnetic tickets and [[Radio-frequency identification|RFID]] |

Fare payment is via a barrier system accepting magnetic tickets and [[Radio-frequency identification|RFID]]-like contactless cards. A rechargeable [[contactless smart card]] called [[Opus card|Opus]] was unveiled on April 21, 2008; it provides seamless integration with other transit networks of neighbouring cities by being capable of holding multiple transport tickets: tickets, books or subscriptions, a subscription for Montreal only and commuter train tickets.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/en/info/fares/opus-cards-and-other-fare-media|title=Opus cards and other fare media|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> Moreover, unlike the [[magnetic stripe card]]s, which had been sold alongside the new Opus cards up until May 2009, the contactless cards are not at risk of becoming demagnetized and rendered useless and do not require patrons to slide them through a reader. |

||

Since 2015, customers have been able to purchase an |

Since 2015, customers have been able to purchase an Opus card reader to recharge their personal card online from a computer.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/montreal/201507/09/01-4884277-la-carte-opus-pourra-etre-rechargee-en-ligne.php|title=La carte OPUS pourra être rechargée en ligne|newspaper=La Presse|language=fr|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> As of April 2024, the ARTM added an option to recharge an Opus card directly from the Chrono mobile app.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Recharge d’une carte OPUS avec un téléphone intelligent |url=https://www.artm.quebec/grands-projets/projet-concerto/recharge-opus/ |access-date=2024-08-10 |website=Autorité régionale de transport métropolitain {{!}} ARTM |language=fr-FR}}</ref> In 2016, the STM is developing a smart phone application featuring NFC technology, which could replace the Opus card.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/stm-mobile-payments-montreal-metro-android-1.3382059|title=STM developing mobile payment system for Android phones|newspaper=CBC News|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

||

===MétroVision=== |

===MétroVision=== |

||

[[File:STM-Metrovision.jpg|thumb|A MétroVision screen at {{stms|Place-des-Arts}} station]] |

[[File:STM-Metrovision.jpg|thumb|A MétroVision screen at {{stms|Place-des-Arts}} station]] |

||

Metro stations are equipped with MétroVision information screens displaying advertising, news headlines |

Metro stations are equipped with MétroVision information screens displaying advertising, news headlines and [[MétéoMédia]] weather information, as well as STM-specific information regarding service changes, service delays and other information about using the system. By the end of 2014, the STM had installed screens in all 68 stations. Berri–UQAM station was the first station to have these screens installed.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/fr/node/792|title=More Screens Added to the Subway System: Another Initiative to Better Inform the Clientele|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 27, 2016}}</ref> |

||

=== Ridership === |

=== Ridership === |

||

| Line 193: | Line 195: | ||

=== Funding === |

=== Funding === |

||

[[File:Place Bonaventure 01.jpg|left|thumb|[[Société de transport de Montréal|STM]] headquarters [[Place Bonaventure]]]] |

[[File:Place Bonaventure 01.jpg|left|thumb|[[Société de transport de Montréal|STM]] headquarters [[Place Bonaventure]]]] |

||

The network operations funding (maintenance, equipment purchase and salaries) is provided by the STM. |

The network operations funding (maintenance, equipment purchase and salaries) is provided by the STM. Tickets and subscriptions cover only 40% of the actual operational costs, with the shortfall offset by the [[urban agglomeration of Montreal]] (28%), the [[Montreal Metropolitan Community]] (5%) and the Government of Quebec (23%).<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=http://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/budget2016.pdf|title=Budget 2016|date=November 17, 2015|website=stm.info|language=fr}}</ref> |

||

The STM does not keep separate accounts for Metro and buses services, therefore the following figures include both activities. In 2016, direct operating revenue planned by the STM totalled $667 million. To compensate for the reduced rates, the city will pay $513 million plus $351 million from Quebec. For a budget of $1.53 billion, salaries account for 57% of expenditures, followed in importance by financial expenses (22%) resulting from a 2.85 billion debt. For the Metro only, wages represented 75% of the $292 million operating costs, before electricity costs (9%).<ref name=":4" /> |

The STM does not keep separate accounts for Metro and buses services, therefore the following figures include both activities. In 2016, direct operating revenue planned by the STM totalled $667 million. To compensate for the reduced rates, the city will pay $513 million plus $351 million from Quebec. For a budget of $1.53 billion, salaries account for 57% of expenditures, followed in importance by financial expenses (22%) resulting from a 2.85 billion debt. For the Metro only, wages represented 75% of the $292 million operating costs, before electricity costs (9%).<ref name=":4" /> |

||

| Line 201: | Line 203: | ||

=== Security === |

=== Security === |

||

[[File:Point assistance metro Montreal.jpg|thumb|Emergency station on a platform]] |

[[File:Point assistance metro Montreal.jpg|thumb|Emergency station on a platform]] |

||

Montreal Metro facilities are patrolled daily by 155 STM inspectors and 115 agents of the [[Service de police de la Ville de Montréal|Montreal Police Service]] (SPVM) assigned to the subway.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ici.radio-canada.ca/regions/montreal/2015/04/17/007-criminalite-metro-securite-stm.shtml|title=Quelle station de métro connaît le plus de crimes et de délits ?|website=Radio-Canada.ca|language=fr|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> They are in contact with the [[Command center|command centre]] of the Metro which has 2,000 cameras distributed on the network, coupled with a computerized visual recognition system.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.tvanouvelles.ca/2012/10/17/visite-du-centre-de-surveillance-de-la-stm|title=Visite du centre de surveillance de la STM|website=TVA Nouvelles|language=fr|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> |

Montreal Metro facilities are patrolled daily by 155 STM inspectors and 115 agents of the [[Service de police de la Ville de Montréal|Montreal Police Service]] (SPVM) assigned to the subway.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ici.radio-canada.ca/regions/montreal/2015/04/17/007-criminalite-metro-securite-stm.shtml|title=Quelle station de métro connaît le plus de crimes et de délits ?|website=Radio-Canada.ca|date=April 17, 2015 |language=fr|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> They are in contact with the [[Command center|command centre]] of the Metro which has 2,000 cameras distributed on the network, coupled with a computerized visual recognition system.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.tvanouvelles.ca/2012/10/17/visite-du-centre-de-surveillance-de-la-stm|title=Visite du centre de surveillance de la STM|website=TVA Nouvelles|date=October 17, 2012 |language=fr|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> |

||

On station platforms, emergency points are available with a telephone connected to the command centre, an emergency power supply cut-off switch and a fire extinguisher.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/fr/infos/reglements/voyager-en-securite/metro|title=Sécurité dans le métro|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> The power supply system is segmented into short sections that can be independently powered, so that following an incident a single train can be stopped while the others reach the nearest station. |

On station platforms, emergency points are available with a telephone connected to the command centre, an emergency power supply cut-off switch and a fire extinguisher.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.stm.info/fr/infos/reglements/voyager-en-securite/metro|title=Sécurité dans le métro|newspaper=Société de transport de Montréal|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> The power supply system is segmented into short sections that can be independently powered, so that following an incident a single train can be stopped while the others reach the nearest station. |

||

In tunnels, a raised path at trains level facilitates evacuation and allows people movement without walking on the tracks. Every 15 meters, directions are indicated by illuminated |

In tunnels, a raised path at trains level facilitates evacuation and allows people movement without walking on the tracks. Every 15 meters, directions are indicated by illuminated green signs. Every 150 meters, emergency stations with telephones, power switches and [[fire hose]]s can be found. At the ventilation shafts locations in the old tunnels or every 750 meters in recent tunnels sections (Laval), emergency exits reach the surface. |

||

On the surface, blue fire hydrants in the streets are [[dry riser]]s connected to the Metro fire control system. If a fire breaks out in tunnels, firefighters connect the red fire hydrant with the blue terminals to power the subway system. This decoupling prevents accidental flooding.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=6497,54397571&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL#jean_rmarcotte|title=Ville de Montréal – L'eau de Montréal – Saviez-vous que...|website=ville.montreal.qc.ca|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> |

On the surface, blue fire hydrants in the streets are [[dry riser]]s connected to the Metro fire control system. If a fire breaks out in tunnels, firefighters connect the red fire hydrant with the blue terminals to power the subway system. This decoupling prevents accidental flooding.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=6497,54397571&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL#jean_rmarcotte|title=Ville de Montréal – L'eau de Montréal – Saviez-vous que...|website=ville.montreal.qc.ca|access-date=October 30, 2016}}</ref> |

||

== Station design == |

== Station design == |

||

{{See also|:Category:Montreal Metro artists|l1=Montreal Metro artists}} |

|||

[[File:WTMTL T32 IMG 8262.JPG|left|thumb|{{stms|Préfontaine}} station entrance building]] |

[[File:WTMTL T32 IMG 8262.JPG|left|thumb|{{stms|Préfontaine}} station entrance building]] |

||

The design of the Metro was heavily influenced by Montreal's winter conditions. Unlike other cities' subways, nearly all station entrances in Montreal are set back from the sidewalk and completely enclosed; usually in small, separate buildings or within building facades. They are equipped with swivelling "butterfly" doors meant to mitigate the wind caused by [[Piston effect|train movements]] that can make doors difficult to open.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/stminfo/160311-infostm.pdf|title=L'effet piston|website=stm.info|language=fr}}</ref> The entire system runs underground and some stations are directly connected to buildings, making the Metro an integral part of Montreal's [[Underground City, Montreal|Underground City]]. |

The design of the Metro was heavily influenced by Montreal's winter conditions. Unlike other cities' subways, nearly all station entrances in Montreal are set back from the sidewalk and completely enclosed; usually in small, separate buildings or within building facades. They are equipped with swivelling "butterfly" doors meant to mitigate the wind caused by [[Piston effect|train movements]] that can make doors difficult to open.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/stminfo/160311-infostm.pdf|title=L'effet piston|website=stm.info|language=fr|access-date=October 29, 2016|archive-date=October 19, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211019094401/https://www.stm.info/sites/default/files/pdf/fr/stminfo/160311-infostm.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> The entire system runs underground and some stations are directly connected to buildings, making the Metro an integral part of Montreal's [[Underground City, Montreal|Underground City]]. |

||

The network has 68 stations, four of which have connections between Metro lines, and five connect to the commuter train network. They are mostly named after streets adjacent to them.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|url=http://www.metrodemontreal.com/faq/index.html|title=Frequently Asked Questions - metrodemontreal.com|website=www.metrodemontreal.com|access-date=October 29, 2016}}</ref> |

The network has 68 stations, four of which have connections between Metro lines, and five connect to the commuter train network. They are mostly named after streets adjacent to them.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|url=http://www.metrodemontreal.com/faq/index.html|title=Frequently Asked Questions - metrodemontreal.com|website=www.metrodemontreal.com|access-date=October 29, 2016}}</ref> |

||

[[File:Portes papillon station namur metro de montreal.jpg|thumb|{{stms|Namur}} swivelling doors]] |

[[File:Portes papillon station namur metro de montreal.jpg|thumb|{{stms|Namur}} swivelling doors]] |

||

The average distance between stations is {{convert|950|m|yd}}, with a minimum in the city centre between {{stms|Peel}} and {{stms|McGill}} stations {{convert|296|m|yd}} and a maximum between {{stms|Berri–UQAM}} and {{stms|Jean-Drapeau}} stations of {{convert|2.36|km|mi}}.<ref name=":3" /> Average station depth is {{convert|15|m}}. The deepest station of the network, {{ |

The average distance between stations is {{convert|950|m|yd}}, with a minimum in the city centre between {{stms|Peel}} and {{stms|McGill}} stations {{convert|296|m|yd}} and a maximum between {{stms|Berri–UQAM}} and {{stms|Jean-Drapeau}} stations of {{convert|2.36|km|mi}}.<ref name=":3" /> Average station depth is {{convert|15|m}}. The deepest station of the network, {{stn|Charlevoix||Montreal}}, has its {{stms|Honoré-Beaugrand}} bound platform located {{convert|29.6|m}} underground. The shallowest stations are {{stms|Angrignon}} and [[Longueuil–Université-de-Sherbrooke (Montreal Metro)|Longueuil-Université-de-Sherbrooke]] terminus, {{convert|4.3|m}} below surface.{{Citation needed|date=May 2011}} |

||

Platforms, {{convert|152.4|m}} long and at least {{convert|3.8|m}} wide, are positioned on either sides of the tracks except in the {{stms|Lionel-Groulx}}, {{stms|Snowdon}} and {{stms|Jean-Talon}} stations, where they are superimposed to facilitate transfers between lines in certain directions. {{ |

Platforms, {{convert|152.4|m}} long and at least {{convert|3.8|m}} wide, are positioned on either sides of the tracks except in the {{stms|Lionel-Groulx}}, {{stms|Snowdon}} and {{stms|Jean-Talon}} stations, where they are superimposed to facilitate transfers between lines in certain directions. {{stn|Charlevoix||Montreal}} and [[De L'Église (Montreal Metro)|De l'Eglise]] stations are designed with bunk platforms for engineering reasons, the basement rock in their area ([[shale]]s) being too brittle for a station with more footprint. The terminus stations of future extensions could be equipped with central platforms to accommodate a [[Balloon loop|turning loop]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/montreal/201305/29/01-4655818-metro-de-montreal-une-refonte-majeure-du-reseau.php|title=Métro de Montréal: une refonte majeure du réseau|last=Bisson|first=Bruno|newspaper=La Presse|language=fr|access-date=October 29, 2016}}</ref> |

||

=== Architectural design and public art === |

=== Architectural design and public art === |

||

| Line 227: | Line 228: | ||

Along with the [[Stockholm metro]], Montreal pioneered the installation of public art in the Metro among capitalist countries,{{Citation needed|date=October 2016}} a practice that beforehand was mostly found in socialist and communist nations (the [[Moscow Metro]] being a case in point). More than fifty stations are decorated with over one hundred works of public art, such as sculpture, stained glass, and murals by noted Quebec artists, including members of the famous art movement, the ''[[les Automatistes|Automatistes]]''. |

Along with the [[Stockholm metro]], Montreal pioneered the installation of public art in the Metro among capitalist countries,{{Citation needed|date=October 2016}} a practice that beforehand was mostly found in socialist and communist nations (the [[Moscow Metro]] being a case in point). More than fifty stations are decorated with over one hundred works of public art, such as sculpture, stained glass, and murals by noted Quebec artists, including members of the famous art movement, the ''[[les Automatistes|Automatistes]]''. |

||

Some of the most important works in the Metro include the stained-glass window at {{stms|Champ-de-Mars}} station, the masterpiece of major Quebec artist [[Marcelle Ferron]]; and the [[Hector Guimard|Guimard]] entrance at Square-Victoria-OACI station, largely consisting of parts from the [[Paris Métro entrances by Hector Guimard|famous entrances]] designed for the [[Paris Métro]], on permanent loan<ref name="loan">Interview Pierre Bourgeau by SRC oct 2006</ref> since 1966 by the [[Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens|RATP]] to commemorate its cooperation in constructing the Metro. Installed in 1967 (the 100th anniversary of Hector Guimard's birth), this is the only authentic Guimard entrance in use outside Paris.{{efn|Although reproductions using original molds were given to Mexico City ([[Bellas Artes metro station (Mexico City)|Bellas Artes station]] on [[Mexico City Metro Line 8|Line 8]]), Chicago ([[Van Buren Street station]] on the [[Metra]] network), Lisbon ([[Picoas (Lisbon Metro)|Picoas]] station on the [[Yellow Line (Lisbon Metro)|Yellow Line]]) and Moscow ([[Kiyevskaya ( |

Some of the most important works in the Metro include the stained-glass window at {{stms|Champ-de-Mars}} station, the masterpiece of major Quebec artist [[Marcelle Ferron]]; and the [[Hector Guimard|Guimard]] entrance at Square-Victoria-OACI station, largely consisting of parts from the [[Paris Métro entrances by Hector Guimard|famous entrances]] designed for the [[Paris Métro]], on permanent loan<ref name="loan">Interview Pierre Bourgeau by SRC oct 2006</ref> since 1966 by the [[Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens|RATP]] to commemorate its cooperation in constructing the Metro. Installed in 1967 (the 100th anniversary of Hector Guimard's birth), this is the only authentic Guimard entrance in use outside Paris.{{efn|Although reproductions using original molds were given to Mexico City ([[Bellas Artes metro station (Mexico City)|Bellas Artes station]] on [[Mexico City Metro Line 8|Line 8]]), Chicago ([[Van Buren Street station]] on the [[Metra]] network), Lisbon ([[Picoas (Lisbon Metro)|Picoas]] station on the [[Yellow Line (Lisbon Metro)|Yellow Line]]) and Moscow ([[Kiyevskaya (Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line)|Kiyevskaya]] station on the [[Arbatsko-Pokrovskaya line]]).}} |

||

===Accessibility=== |

===Accessibility=== |

||

[[File:Station Rosemont 67.JPG|left|thumb|{{stms|Rosemont}} station elevator |

[[File:Station Rosemont 67.JPG|left|thumb|{{stms|Rosemont}} station elevator under construction, 2016]] |

||

The Montreal Metro |

The Montreal Metro was a late adopter of accessibility compared to many metro systems (including those older than the Metro), much to the dismay and criticism of accessibility advocates in Montreal.<ref>{{cite web |last=Sutherland |first=Anne |url=https://montrealgazette.com/opinion/M%C3%A9tro+elevator+plans+stall/3984059/story.html |title=Métro elevator plans stall |publisher=Montrealgazette.com |date=December 15, 2010 |access-date=March 10, 2011 }}{{Dead link|date=May 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The first accessible stations on the system were the three stations in Laval, {{stms|Cartier}}, [[De La Concorde (Montreal Metro)|De la Concorde]] and {{stms|Montmorency}}, which opened in 2007 as part of the Orange Line extension. Four existing stations{{snd}}{{stms|Lionel-Groulx}}, {{stms|Berri–UQAM}}, {{stms|Henri-Bourassa}}, and {{stms|Côte-Vertu}}{{snd}}were made accessible between 2009 and 2010.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.journalmetro.com/linfo/article/310223--les-ascenseurs-des-stations-lionel-groulx-et-berri-uqam-maintenant-en-service |title="Les ascenseurs des stations Lionel-Groulx et Berri-UQAM maintenant en service." ''Métro'' (Montreal). September 14, 2009. Retrieved September 20, 2009 |publisher=Journalmetro.com |date=December 21, 2010 |access-date=March 10, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110727075321/http://www.journalmetro.com/linfo/article/310223--les-ascenseurs-des-stations-lionel-groulx-et-berri-uqam-maintenant-en-service |archive-date=July 27, 2011}}</ref> |

||

As of |