Isaias Afwerki: Difference between revisions

no-party he is recognized like a dictator Tag: Reverted |

|||

| (376 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|President of Eritrea since 1993}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2021}} |

|||

{{Hatnote|In this [[Eritrean name]], the name Afwerki is a [[patronymic]], and the person should be referred by the [[given name]], Isaias.}} |

|||

{{Short description|President of Eritrea}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2024}} |

|||

{{patronymic name|3=his}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

| honorific-prefix = [[His Excellency]] |

| honorific-prefix = [[Excellency|His Excellency]] |

||

| native_name = ኢሳይያስ ኣፍወርቂ |

| native_name = {{nobold|ኢሳይያስ ኣፍወርቂ}} |

||

| image = |

| image = Isaias Afwerki 2024 (cropped).jpg |

||

| caption = Isaias in |

| caption = Isaias in 2024 |

||

| |

| order = 1st |

||

| office = List of heads of state of Eritrea{{!}}President of Eritrea |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date and age|1946|2|2|df=y}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Asmara]], [[British Military Administration (Eritrea)|British Military Administration in Eritrea]] <br />{{small|(now [[Eritrea]])}} |

|||

| office = [[List of heads of state of Eritrea|President of Eritrea]] |

|||

| term_start = 24 May 1993 |

| term_start = 24 May 1993 |

||

| term_end = |

| term_end = |

||

| predecessor = '' |

| predecessor = ''Office established'' |

||

| successor = |

| successor = |

||

| office1 = President of the [[National Assembly of Eritrea|National Assembly]] |

| office1 = President of the [[National Assembly of Eritrea|National Assembly]] |

||

| term_start1 = 24 May 1993 |

| term_start1 = 24 May 1993 |

||

| term_end1 = |

| term_end1 = |

||

| predecessor1 = '' |

| predecessor1 = ''Office established'' |

||

| successor1 = |

| successor1 = |

||

| office2 = Chairman of the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] |

| office2 = Chairman of the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] |

||

| term_start2 = February 1994 |

| term_start2 = 16 February 1994 |

||

| term_end2 = |

| term_end2 = |

||

| predecessor2 = '' |

| predecessor2 = ''Party established'' |

||

| successor2 = |

| successor2 = |

||

| office3 = Secretary-General of the [[Provisional Government of Eritrea]] |

| office3 = Secretary-General of the [[Provisional Government of Eritrea]] |

||

| term_start3 = |

| term_start3 = 27 April 1991 |

||

| term_end3 = 24 May 1993 |

| term_end3 = 24 May 1993 |

||

| predecessor3 = '' |

| predecessor3 = ''Office established'' |

||

| successor3 = '' |

| successor3 = ''Office abolished'' |

||

| office4 = Leader of the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] |

| office4 = Leader of the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] |

||

| term_start4 = 12 January 1987 |

| term_start4 = 12 January 1987 |

||

| term_end4 = February 1994 |

| term_end4 = 16 February 1994 |

||

| predecessor4 = Romodan Mohammed Nur |

| predecessor4 = [[Romodan Mohammed Nur]] |

||

| successor4 = '' |

| successor4 = ''Party dissolved'' |

||

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|1946|02|02|df=y}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Asmara]], [[British Military Administration in Eritrea|British Administration in Eritrea]]<br />(present-day [[Eritrea]]) |

|||

| party = [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] |

| party = [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] |

||

| spouse = Saba Haile |

| spouse = Saba Haile |

||

| children = |

| children = 3 |

||

| education = [[Addis Ababa University]] (dropped out) |

|||

* Abraham |

|||

* Elsa |

|||

* Berhane}} |

|||

| signature = Isaias Afwerki's Signature.svg |

| signature = Isaias Afwerki's Signature.svg |

||

| allegiance = [[Eritrean Liberation Front|ELF]] (1966–1969)<br/>[[Eritrean People's Liberation Front|EPLF]] (1970–1994) |

|||

| battles = [[Eritrean War of Independence]]<br>[[Eritrean Civil War]]s |

|||

| nationality = Eritrean |

|||

| serviceyears = 1966–1991 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Isaias Afwerki''' ({{ |

'''Isaias Afwerki''' ({{langx|ti|ኢሳይያስ ኣፍወርቂ}},<ref>{{cite news|title=ፕረዚደንት ኢሳይያስ ኣፍወርቂ፡ ኣብ መልእኽቲ ሓድሽ ዓመት እንታይ ኣመልኪቱ?|date=2023-01-01|publisher=[[BBC World Service]]|lang=ti|url=https://www.bbc.com/tigrinya/articles/cz5ynvxkl86o.amp|accessdate=2024-05-21}}</ref> {{IPA-ti|isajas afwɐrkʼi|pron|En-us-Isaias Afwerki from Eritrea pronunciation (Voice of America).oga}}; born 2 February 1946)<ref>{{Cite web |date=1 May 2014 |title=President: Isaias Afwerki |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13349076 |access-date=18 December 2018 |website=BBC News |publisher=The BBC |archive-date=10 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181010202255/https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-13349076 |url-status=live }}</ref> is an Eritrean politician and partisan who has been the first and only [[List of heads of state of Eritrea|president of Eritrea]] since 1993. In addition to being president, Isaias has been the chairman of Eritrea's [[One-party state|sole legal political party]], the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] (PFDJ). |

||

Isaias joined the pro-independence [[Eritrean Liberation Front]] in 1966 and quickly rose through the ranks to become its leader in 1970, before defecting to form the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] (EPLF). Having consolidated power within this group, he led pro-independence forces to victory on 24 May 1991, ending the 30-year-old [[Eritrean War of Independence|war for independence]] from Ethiopia,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Perlez |first=Jane |date=16 June 1991 |title=Eritreans, Fresh From Victory, Must Now Govern |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/16/world/eritreans-fresh-from-victory-must-now-govern.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161126194943/http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/16/world/eritreans-fresh-from-victory-must-now-govern.html |archive-date=26 November 2016 |access-date=26 March 2021 |work=[[The New York Times]]}}</ref> before being elected president of the newly-founded country of Eritrea two years later. |

|||

Isaias is the chairperson of Eritrea's [[One-party state|sole legal political party]], the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] (PFDJ). He has faced accusations of [[totalitarianism]] and been cited for [[human rights]] violations by the [[United Nations]] and [[Amnesty International]].<ref name="NYT_torture_widespread" /><ref name="Amnesty_rampant_repression" /> In 2021, [[Reporters Without Borders]] ranked Eritrea, under the government of Isaias, last out of 180 countries in its [[Press Freedom Index]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=20 April 2020 |title=2021 World Press Freedom Index |url=https://rsf.org/en/ranking/2021 |access-date=21 April 2021 |website=RSF - Reporters without borders}}</ref> |

|||

Western scholars and historians have long considered Isaias to be a dictator, with Eritrea's [[Constitution of Eritrea|constitution]] remaining unenforced, electoral institutions effectively being nonexistent as well as a policy of [[Conscription in Eritrea|mass conscription]].<ref name="ochr">{{Cite web |title=OHCHR Report of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea |url=https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-i-eritrea/report-co-i-eritrea-0 |access-date=2022-11-20 |website=OHCHR |language=en |archive-date=13 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221013112741/http://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/co-i-eritrea/report-co-i-eritrea-0 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="hrw">{{Citation |last=Human Rights Watch |title=Eritrea: Events of 2016 |date=2017-01-12 |url=https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/eritrea |work=English |access-date=2022-11-20 |language=en |archive-date=23 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180823070518/https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2017/country-chapters/eritrea |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="bbc18">{{Cite news |date=2018-07-09 |title=Can Ethiopia's Abiy Ahmed make peace with 'Africa's North Korea'? |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |first=Fergal |last=Keane |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44771292 |access-date=2022-11-20 |archive-date=11 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181011144855/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44771292 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=The brutal dictatorship the world keeps ignoring |language=en-US |newspaper=The Washington Post |first=Adam |last=Taylor |date=12 June 2015 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/06/12/the-brutal-dictatorship-the-world-keeps-ignoring/ |access-date=2022-11-20 |issn=0190-8286 |archive-date=30 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210730161041/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/06/12/the-brutal-dictatorship-the-world-keeps-ignoring/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="de Waal">{{Cite news |first=Alex |last=de Waal |date=2022-09-02 |title=The Despotism of Isaias Afewerki |work=The Baffler |language=en-US |url=https://thebaffler.com/latest/the-despotism-of-isaias-afewerki-de-waal |access-date=2023-05-18 |archive-date=4 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220904232946/https://thebaffler.com/latest/the-despotism-of-isaias-afewerki-de-waal |url-status=live }}</ref> The [[United Nations]] and [[Amnesty International]] have cited him for [[human rights violations]].<ref name="NYT_torture_widespread">{{Cite news |last=Cumming-Bruce |first=Nick |date=8 June 2015 |title=Torture and Other Rights Abuses Are Widespread in Eritrea, U.N. Panel Says |work=[[The New York Times]] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/09/world/africa/eritrea-human-rights-abuses-afwerki-un-probe-crimes-against-humanity-committed.html |url-status=live |access-date=30 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200709220607/https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/09/world/africa/eritrea-human-rights-abuses-afwerki-un-probe-crimes-against-humanity-committed.html |archive-date=9 July 2020 |quote=has imposed a reign of fear through systematic and extreme abuses of the population that may amount to crimes against humanity}}</ref><ref name="Amnesty_rampant_repression">{{Cite web |date=9 May 2013 |title=Eritrea: Rampant repression 20 years after independence |url=https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/05/eritrea-rampant-repression-years-after-independence/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200809020019/https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2013/05/eritrea-rampant-repression-years-after-independence/ |archive-date=9 August 2020 |access-date=27 March 2022 |publisher=Amnesty International |language=en}}</ref> In 2024, [[Reporters Without Borders]] ranked Eritrea, under the government of Isaias, last out of 180 countries in its [[Press Freedom Index]].<ref name="rsf">{{cite web |year=2024 |title=2024 World Press Freedom Index |url=https://rsf.org/en/index |work=Reporters Without Borders |access-date=12 May 2022 |archive-date=7 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220507020451/https://rsf.org/en/index |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Early and personal life== |

|||

Isaias Afwerki was born in the Aba Shi'Aul district of [[Asmara]], Eritrea.<ref name="GlobalSecurity_2015_Isaias_profile" /><ref name="Historical Dictionary of Eritrea2010">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SYsgpIc3mrsC&q=Isaias+Afwerki&pg=PA313 |title=Historical Dictionary of Eritrea |date=14 October 2010 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-810-87505-0 |edition=2nd |page=313}}</ref> |

|||

==Early life and education== |

|||

Isaias attended Prince Makonnen High School (PMSS). In the early 1960s, he joined the nationalist Eritrean student movement.<ref name="Dictionary of African Biography2012" /> In 1965, he began his studies at the College of Engineering at Haile Selassie I University (now called [[Addis Ababa University]]) in [[Addis Ababa]], Ethiopia.<ref name="Dictionary of African Biography2012">{{Cite book |last=Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+born+1946&pg=RA2-PA160 |title=Dictionary of African Biography |last2=Steven J. Niven |date=2 February 2012 |publisher=OUP, US |isbn=978-0-19-538207-5 |pages=160–161}}</ref> |

|||

Isaias Afwerki was born on 2 February 1946<ref name=":IsaiasWashPost">{{cite news|title=Eritrea's President, His Excellency Isaias Afwerki|date=2000-04-07|newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/liveonline/00/world/afwerki_040700.htm|access-date=2024-01-01|archive-date=16 August 2000|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000816030836/http://washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/liveonline/00/world/afwerki_040700.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last=Plaut|first=Martin|title=Who is Is Isaias Afwerki, Eritrea's Enigmatic Dictator?|date=2016-11-01|website=[[Newsweek]]|url=https://www.newsweek.com/who-isaias-afwerki-eritreas-enigmatic-dictator-515761|access-date=2024-01-01|archive-date=2 January 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240102030127/https://www.newsweek.com/who-isaias-afwerki-eritreas-enigmatic-dictator-515761|url-status=live}}</ref> in the Aba Shi'Aul district of Asmara. His father, whose native village was Tselot, just outside of Asmara, was a minor functionary in the state tobacco monopoly, his mother was descended from [[Tigrayans|Tigrayan]] immigrants from the [[Enderta (Ethiopian District)|Enderta]] area [[Tigray ]]region of [[Ethiopia]].<ref>{{harvnb|Connell|Killion|2011|p=313}}</ref> |

|||

Isaias spent most of his youth in Asmara. He attended Prince Makonnen High School (PMSS)(now called Asmara Secondary School) where he engaged in discussions about nationalist Eritrean politics.<ref name="Dictionary of African Biography2012" /> In 1965, he began his studies at the College of Engineering at Haile Selassie I University (now called [[Addis Ababa University]]) in [[Addis Ababa]], Ethiopia, but due to lower scores in his first-year first semester he was supposed to retake the first semester which he didn't. However, he maintained his interest in Eritrean politics and informed his friends that he was planning to join the Eritrean rebels in the field.<ref name="Dictionary of African Biography2012">{{Cite book |last1=Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+born+1946&pg=RA2-PA160 |title=Dictionary of African Biography |last2=Steven J. Niven |date=2 February 2012 |publisher=OUP, US |isbn=978-0-19-538207-5 |pages=160–161 |access-date=2 October 2020 |archive-date=18 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230918084214/https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+born+1946&pg=RA2-PA160 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Plaut |first1=Martin |title=Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa's Most Repressive State |pages=109}}</ref> |

|||

Isaias met his wife, Saba Haile, in a village called Nakfa in the summer of 1981. They have three children: Abraham, Elsa, and Berhane.<ref>{{Cite web |year=2010 |title=Biography of Isaias Afwerki |url=http://www.madote.com/2010/11/president-isaias-afwerkis-biography.html |publisher=Madote}}</ref><ref>Hillary Rodham Clinton (2003), Oxford Dictionary of African Biography. Simon & Schuster, {{ISBN|0743222253}}.</ref><ref>Michela Wrong (2005), I Didn't Do it for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation. Fourth Estate, {{ISBN|9780007150960}}.</ref> |

|||

== Eritrean War of Independence == |

|||

Shortly before Eritrea declared independence, Isaias contracted [[Malaria|cerebral malaria]] and was flown to Israel for treatment.<ref>{{Cite news |date=12 June 2019 |title=Eritrea's 'ice bucket' bid to oust Isaias Afwerki |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48034365}}</ref> Arriving in a coma, he was treated at [[Sheba Medical Center]], where his life was saved.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Melman |first=Yossi |date=20 November 2020 |title=Israel, help us overthrow this autocratic regime] |work=[[Haaretz]] |url=https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-please-help-us-overthrow-eritrea-s-autocratic-regime-1.9317083 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20210118032937/https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-please-help-us-overthrow-eritrea-s-autocratic-regime-1.9317083 |archive-date=18 January 2021}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main article|Eritrean War of Independence}} |

|||

In September 1966, Isaias along with [[Haile Woldense]] and [[Mussie Tesfamichael]] traveled to [[Kassala, Sudan]], via Asmara to join the [[Eritrean Liberation Front]] (ELF). Isaias and his comrades had assumed the ELF was an inclusive revolutionary organization, but they soon realized that the movement was sectarian and generally hostile to Christians. Isaias, Haile and Mussie decided to organized subvertly, forming a secret clandestine cell. To seal their pact the three men signed an oath with their own blood, carving an 'E' on their right arms, symbolizing their determination to die for Eritrea. In 1967, the [[Government of the People's Republic of China|Chinese government]] took in five ELF recruits for political commissar training. Among those recruits were Isaias where he studied [[Maoism]] as well as the strategy and tactics of guerrilla warfare. On his return trip he was arrested by [[Saudi Arabia]]n authorities{{why?|date=October 2024}} while attempting to cross the [[Red Sea]] on a dhow, he was released nearly six months later.<ref name="Oxford" /> |

|||

Upon his return in 1968, Isaias was appointed as a political commissioner of the ELF's Zone 5 in the [[Hamasien]] region. He and other ELF members began to criticize the sectarian tendencies of the ELF. In 1969, further power struggles among the ELF leadership and the assassination of several Christian members led to the deflection of the ELF's Zone 5 which included Isaias. This group of around seventy fighters, led by Abraham Tewolde, withdrew to an isolated locality, Ala in northeast of the [[Akele Guzay]] near [[Dekemhare]] where they were joined by another small contingent of [[Kebessa]] fighters under [[Mesfin Hagos]], together they became known as the Ala group. Following Tewolde's death in late 1970, Isaias became the leader of the group.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pool |first1=David |title=From guerrillas to government: the Eritrean People's Liberation Front |pages=67}}</ref> |

|||

His nickname "Isu" was frequently used in conversation, including to refer to Isaias in his political capacity, and has appeared in news articles as well.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Isu-virus Demands the Eritrean Pro-Justice Movement to Forge Alliance With The Regional (YES-SEDS) Diaspora Communities |url=https://archive.assenna.com/isu-virus-demands-the-eritrean-pro-justice-movement-to-forge-alliance-with-the-regional-yes-seds-diaspora-communities/ |access-date=5 October 2021 |publisher=Assena}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The war in Tigray: Abiy, Isaias, and the Amhara elite |url=https://www.theafricareport.com/62232/the-war-in-tigray-abiy-isaias-and-the-amhara-elite/#:~:text=In%20the%20Millennium%20Hall%2C%20thousands%20of%20Addis%20Ababa%20elites%20gathered%20to%20give%20Isaias%20the%20reception%20of%20his%20life%2C%20with%20thunderous%20cries%20of%20%E2%80%9CIsu!%20Isu!%E2%80%9D%20resonating%20in%20the%20hall. |access-date=5 October 2021 |publisher=The Africa Report}}</ref> |

|||

In August 1971, this group of Christian deflectors held a meeting at Tekli (northern Red Sea) and founded the ''Selfi Natsinet'' (“Party of Independence“). They elected a leadership consisting of Isaias, [[Mesfin Hagos]], Tewolde Eyob, Solomon Woldemariam and Asmerom Gerezgiher. They then issued a highly polemical document written by Isaias called, ''Nihnan Elamanan'' (“We and Our Goals”), in which they explained the rationale for their decision to create a separate political organization instead of working within the ELF.<ref name="Oxford">{{Cite book |last=Akyeampong |first=Emmanuel Kwaku |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+biography&pg=RA2-PA160 |title=Dictionary of African Biography |date=2012 |publisher=Oxford University Press, USA |isbn=9780195382075 |language=en |access-date=2 October 2020 |archive-date=18 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230918084118/https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+biography&pg=RA2-PA160 |url-status=live }}</ref> The document accused the ELF of discriminating against Christian highlanders and killing reformist Christian ELF members. The document instead stressed the unity of the Eritrean nation and called for a "revolutionary organization with a revolutionary line". In August 1971, Selfi Natsinet joined the [[Popular Liberation Forces]] (PLF), forming a loose alliance with two other splinter groups, these three groups were jointly represented by [[Osman Saleh Sabbe]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pool |first1=David |title=From guerrillas to government: the Eritrean People's Liberation Front |pages=68}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Negash |first1=Tekeste |title=Eritrea and Ethiopia The Federal Experience |pages=153 |url=https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:272775/FULLTEXT01.pdf |access-date=8 March 2024 |archive-date=3 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240303013253/https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:272775/FULLTEXT01.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Eritrean independence movement== |

|||

In September 1966, Isaias left the university where he was studying and traveled to Kassala, Sudan, via Asmara to join the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). In 1967, the [[Government of the People's Republic of China|Chinese government]] donated light weapons and a small amount of cash to cover the cost of transport and provided training to ELF combatants. Isaias was among the first group that went to China in 1967 where he received intensive military training. Upon his return, he was appointed as a political commissioner of the ELF's Zone 5 in the Hamasen region.<ref name="Oxford" /> |

|||

In February 1972, the ELF declared war on the PLF resulting in a [[Eritrean Civil Wars#First Civil War|civil war]] that would last until 1974. During this time, a significant number of Asmara high school and University of Addis Ababa students were recruited which resulted in the Selfi Natsinet becoming the most powerful group within the PLF. A major crisis occurred when the Obel faction led by the former Sudanese army NCO Abu Tayyara, left the group in April 1973. Isaias then called for a more unified administration and military force, which led to the emergence of the [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front]] (EPLF) in August 1973. Internal agitation soon arose when the [[Marxist]] faction, led by his old friend Mussie Tesfamichael, called for more radical policies and began to accuse the movement of being too authoritarian. Isaias denounced his rivals in a publication and mobilized his supporters to arrest Mussie and other colleagues. After a brief trial, all eleven EPLF leaders including Mussie were executed on 11 August 1974. In 1977, EPLF held its first congress, at which Isaias was elected vice-secretary general.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pool |first1=David |title=From guerrillas to government: the Eritrean People's Liberation Front |pages=84}}</ref> |

|||

Isaias played a key role in the grassroots movement which rapidly gathered momentum and brought about the demise of the zonal divisions of the liberation army. Further, he played a vital role in the Tripartite Union, which challenged the ELF's leadership, the Supreme Council (Cairo), and the Revolutionary Command (Kassala). Soon after the commencement of sectarian violence in the early 1970s against members of the reform movement, those who were in the central highlands, including Isaias, withdrew to an isolated locality, Ala in northeastern AkkeleGuzay near Dekemhare. Here, they joined Abraham Tewolde, the former commander of the defunct Zone 5. Isaias became the leader after Abraham Tewolde died in battle.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

Although Isaias had to initially share power with others who led the EPLF, by the early 1980s he was able to transform it into the movement he envisioned. The EPLF became a tough nationalist organization controlled by a highly centralized inner party which made all the important decisions. From the mid 1980s, Isaias made a bid to marginalize the political core of the EPLF's founding leadership and pack the political bodies with men unwaveringly loyal to him. This coincided with the second congress of the EPLF in 1987, when he was elevated to the status of secretary-general of the organization. According to Dan Connell, this was approximately when Isaias took unquestioned control of the EPLF. As the leader of the Eritrean struggle against Ethiopian rule, Isaias became the icon of the resistance. In April 1991, the EPLF took Asmara from Ethiopian forces; the following month, they drove out Derg troops in the area. After the Derg was overthrown by the EPRDF on 28 May, Isaias quickly obtained U.S. support for Eritrean independence; in June 1991, his organization announced their desire to hold a United Nations-sponsored referendum.<ref name=":12">{{Cite book |last=Stapleton |first=Timothy J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VfdwEAAAQBAJ&dq=isaias+afwerki&pg=PA5 |title=Modern African Conflicts: An Encyclopedia of Civil Wars, Revolutions, and Terrorism |date=2022-06-30 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-4408-6970-9 |language=en |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017140756/https://books.google.com/books?id=VfdwEAAAQBAJ&dq=isaias+afwerki&pg=PA5 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Plaut |first1=Martin |title=Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa's Most Repressive State |pages=110}}</ref> |

|||

==Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF)== |

|||

In August 1971, a group of younger ELF members held a meeting at Tekli (northern Red Sea) and founded ''Selfi Natsinet'', commonly known as the Peoples Liberation Force (PLF). The group elected five leaders, including Isaias. Less than two months later, in October 1971, the group formed a committee to draft and issue a highly polemical document, ''Nihnan Elamanan'' (“We and Our Goals”), in which they explained in detail the rationales for their decision to create a separate political organization instead of working within the ELF.<ref name="Oxford">{{Cite book |last=Akyeampong |first=Emmanuel Kwaku |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39JMAgAAQBAJ&q=Isaias+Afwerki+biography&pg=RA2-PA160 |title=Dictionary of African Biography |date=2012 |publisher=Oxford University Press, USA |isbn=9780195382075 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Presidency (1993–present){{Anchor|Eritrea under Isaias Afwerki}} == |

|||

In 1977, EPLF held its first congress, at which Isaias was elected vice-secretary general. During the second congress of the EPLF in 1987, he was elevated to the status of secretary-general of the organization and in May 1991 became secretary-general of the Provisional Government of Eritrea. In April 1993, after a national referendum, he was elected as the president of the State of Eritrea by the National Assembly. In February 1994, the EPLF held its third congress, and Isaias was elected secretary-general of the Peoples Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) by an overwhelming majority of votes.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

{{Further|Politics of Eritrea}} |

|||

=== Independence of Eritrea === |

|||

==Post-independence== |

|||

{{Main|1993 Eritrean independence referendum}} |

|||

{{See also|Politics of Eritrea}} |

|||

In April 1993, a [[United Nations]]-supervised [[1993 Eritrean independence referendum|referendum]] on independence was held, and the following month Eritrea achieved ''[[de jure]]'' independence. Isaias was elected as the president of the State of Eritrea by the [[National Assembly (Eritrea)|National Assembly]] and declared the first [[head of state]], a position he has held ever since the end of the war for independence.<ref name="BBC2018" /> |

|||

[[File:Isaias Afwerki in 2002.jpg|thumb|180px|Isaias in 2002]] |

|||

[[File:Donald Rumsfeld with Isaias Afwerki.jpg|thumb|President Isaias Afwerki with U.S. Secretary of Defense [[Donald Rumsfeld]], December 2002]] |

|||

In April 1993, a [[United Nations]]-supervised [[1993 Eritrean independence referendum|referendum]] on independence was held, and the following month Eritrea achieved ''[[de jure]]'' independence. Isaias was declared the first [[head of state]], a position he has held ever since the end of the war for independence.<ref name="BBC2018" /> |

|||

On 16 February 1994, the EPLF held its third congress, renamed itself the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] (PFDJ) as part of its transition to a political party and Isaias was elected secretary-general by an overwhelming majority of votes.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Markakis |first=John |date=1995 |title=Eritrea's National Charter |journal=Review of African Political Economy |volume=22 |issue=63 |pages=126–129 |doi=10.1080/03056249508704109 |jstor=4006283 |issn=0305-6244 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Isaias undertook a series of economic reforms. He implemented a national service program in May 1994 in which individuals would serve for 18 months.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} Military training was the focus for the first six months, followed by awareness{{vague|date=October 2024}} of the country and expansion of its agricultural sector.<ref name=":12"/> |

|||

During the first few years of Isaias' administration, the institutions of governance were structured and put in place. This included the provision of an elected [[Community Courts of Eritrea|local judicial system]], as well as an expansion of the educational system into as many regions as possible.{{citation needed|date=December 2011}} The EPLF renamed itself the [[People's Front for Democracy and Justice]] (PFDJ) in February 1994 as part of its transition to a political party.{{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} He was hailed as a new type of African president. Then-US President Bill Clinton referred to him as a "renaissance African leader".<ref name="BBC2018" /> |

|||

=== Domestic policy === |

|||

In this sense, he strongly advocates the necessity for the development of indigenous political and economic institutions, while maintaining that Eritrea must pursue a development strategy that suits its internal conditions and available resources.<ref>{{Cite web |date=21 October 2009 |title=FACTBOX - Key quotes from Eritrean president |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLL474000 |publisher=Reuters}}</ref> The key element of such a policy includes ambitious infrastructure development campaigns both in terms of power, transport, and telecommunications, as well as with basic healthcare and educational facilities.<ref>{{Cite web |title=TimesInterview with Eritrea's Isaias Afewerki |url=https://www.ft.com/content/35b8905c-a44b-11de-92d4-00144feabdc0 |access-date=7 December 2018 |publisher=Financial Times}}</ref> |

|||

==== Elections ==== |

|||

Isaias oversaw an unexpected transformation of Eritrea's relations with Ethiopia in 2018. In June 2018, Ethiopia's newly elected prime minister [[Abiy Ahmed]] negotiated an end to the border war between the countries, including reciprocal visits by Isaias and Abiy in July 2018. Diplomatic and commercial ties between Ethiopia and Eritrea were re-established, and on 9 July 2018, the two leaders signed a Joint Declaration of Peace and Friendship that ended the state of war between their countries,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Isaias Afwerki |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaias-Afwerki |access-date=7 December 2018 |publisher=Encyclopedia Britannica}}</ref> and enunciated a framework of bilateral cooperation in the political, cultural, economic and security fields. This was widely acknowledged by numerous world leaders with the UAE Government awarding Isaias Afwerki the [[Order of Zayed]] (First Class) in recognition of his efforts to end the conflict.<ref>{{Cite web |date=24 July 2018 |title=UAE President awards Order of Zayed to Eritrean President, Ethiopian Prime Minister |url=http://wam.ae/en/details/1395302700507 |publisher=Emirates News Agency}}</ref> As part of closer ties between the two countries, the [[List of intelligence agencies#Ethiopia|Ethiopian]] and [[List of intelligence agencies#Eritrea|Eritrean intelligence agencies]] started close cooperation after July 2018, which worried Eritrean refugees in [[Addis Ababa]], some of whom were temporarily detained for three weeks during the [[Tigray War]], acquitted by Ethiopian courts, and only released two weeks after their acquittal.<ref name="Awate_Eritreans_in_ET_fear" /> |

|||

[[File:Defense.gov News Photo 021210-D-2987S-057.jpg|thumb|227x227px|[[President of Eritrea|President]] Isaias with U.S. [[United States Secretary of Defense|Secretary of Defense]] [[Donald Rumsfeld]], December 2002]]In his first few years Isaias was hailed as a new type of African president with then-US President [[Bill Clinton]] referring to him as a "renaissance African leader". However, in 1997, a new constitution was drawn up, but never enacted, and elections were cancelled.<ref name=":03">{{Cite web |last=Plaut |first=Martin |title=Eritrea's Isaias Afwerki: a tactical authoritarian who might be president for life |url=http://theconversation.com/eritreas-isaias-afwerki-a-tactical-authoritarian-who-might-be-president-for-life-147963 |access-date=2022-05-28 |website=The Conversation |date=25 October 2020 |language=en |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017141339/https://theconversation.com/eritreas-isaias-afwerki-a-tactical-authoritarian-who-might-be-president-for-life-147963 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="BBC2018" /> In an April 2000 speech at [[Princeton University]], Isaias said that "constitutionality, political pluralism and free and fair elections are naturally the best institutional tools" for achieving economic prosperity given the political and cultural realities of a specific country.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Palmer |first=Mark |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SATc3grT0cAC&pg=PA196 |title=Breaking the Real Axis of Evil: How to Oust the World's Last Dictators by 2025 |date=2005 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-7425-3255-7 |language=en |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017141006/https://books.google.com/books?id=SATc3grT0cAC&pg=PA196 |url-status=live }}</ref> However, a parliamentary election scheduled in 2001 was later postponed indefinitely. Although police are responsible for upholding internal security and the armed forces' external security, eyewitness reports exist of the armed forces engaging with demobilizing soldiers or civilian militias to complete the hybrid tasks of both. Civil authorities sometimes involve themselves with security forces in an [[abuse of power]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-12-09 |title=Eritrea-Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2020 |url=https://er.usembassy.gov/title-2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices-eritrea/ |access-date=2022-05-28 |website=U.S. Embassy in Eritrea |language=en-US |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017140435/https://er.usembassy.gov/title-2020-country-reports-on-human-rights-practices-eritrea/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In 2018, Isaias' former comrade, Andebrhan Welde Giorgis, said that Isaias went on to personalise power, and "having personalised power, he abused it to the maximum". Notwithstanding, during the African Unity summit in Cairo in 1993, Isaias had criticized other leaders for staying in power for too long, and he had also rejected a cult of personality.<ref name="BBC2018" /> |

|||

===Tigray War=== |

|||

{{POV section|date=June 2021}} |

|||

During the [[Tigray War]], that started on 4 November 2020 with a surprise attack on the Northern Command center of the [[Ethiopian National Defense Force]] (ENDF) by TPLF affiliated forces, there was widely acknowledged close cooperation between the ENDF and the [[Eritrean Defence Forces]] (EDF).<ref>{{Citation |title=Tigray crisis: Eritrea's role in Ethiopian conflict |date=28 December 2020 |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55295650 |work=BBC News |access-date=28 December 2020}}</ref> The war began after the TPLF, Tigray's ruling party, attacked the camps of the ENDF in Tigray and pushed them to Eritrea. The Eritrean forces joined hands with the ENDF and allegedly with the help of UAE armed drones counter-attacked the TPLF forces. There was alleged [[looting]] in [[Tigray Region]], including systematic, wide-scale looting in [[Aksum]] following the [[Aksum massacre]] in late November 2020.<ref>{{Cite web |date=26 February 2021 |title=The massacre in Axum |url=https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity |access-date=27 February 2021 |website=[[Amnesty International]]}}</ref> |

|||

In 2000, 15 ministers (including his vice president) wrote an open letter asking him to step down.<ref name="joh">{{Cite web |date=2018-04-11 |title=MERON ESTEFANOS, A CONVERSATION ON ERITREA WITH THOR HALVORSSEN, 18 min |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IQdeQ-9nXow |access-date=2023-05-18 |website=OFFinJOBURG |language=en |archive-date=18 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230518095207/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IQdeQ-9nXow |url-status=live }}</ref>{{rp|8:56}} On September 18, 2001, he closed the national press and prominent opposition leaders were arrested.<ref name="britannica">{{Cite web |title=Isaias Afwerki |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaias-Afwerki |access-date=7 December 2018 |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |archive-date=9 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181209124747/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isaias-Afwerki |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2010, when asked when elections would be held, he responded "Let's wait 3 or 4 decades".<ref name="joh" />{{rp|10:41}} |

|||

After several weeks of Ethiopian government denial of the presence of Eritrean troops in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Prime Minister admitted to the presence of Eritrean troops in Ethiopia and agreed to withdraw them. Under international pressure, on 26 March 2021, after a meeting between Ethiopian Prime Minister [[Abiy Ahmed]] and Isaias, it was announced that Eritrean troops will withdraw from the [[Tigray Region]]. As of 30 June 2021, the Eritrean forces had yet to withdraw from Tigray.<ref>{{Cite news |last=AP and AFP |date=26 March 2021 |title=Ethiopian PM: Eritrean troops to leave Tigray |work=[[Deutsche Welle]] |url=https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopian-pm-eritrean-troops-to-leave-tigray/a-57009807 |access-date=26 March 2021}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=26 February 2021 |title=Ethiopia: Eritrean troops' massacre of hundreds of Axum civilians may amount to crime against humanity |work=Amnesty International |url=https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity/ |access-date=5 April 2021 |quote=On 19 November 2020, Ethiopian and Eritrean military forces took control of Axum in a large-scale offensive, killing and displacing civilians with indiscriminate shelling and shooting. In the nine days that followed, the Eritrean military engaged in widespread looting of civilian property and extrajudicial executions. Witnesses could easily identify the Eritrean forces. They drove vehicles with Eritrean license plates, wore distinctive camouflage and footwear used by the Eritrean army and spoke Arabic or a dialect of Tigrinya not spoken in Ethiopia. Some bore the ritual facial scars of the Ben Amir, an ethnic group absent from Ethiopia. Finally, some of the soldiers made no secret of their identity; they openly told residents they were Eritrean.}}</ref> |

|||

== |

==== Economics ==== |

||

{{Main|Economy of Eritrea}} |

|||

In June 2015, a United Nations panel accused Isaias of leading a [[totalitarian government]] responsible for systematic [[human rights violations]] [[human rights in Eritrea|in Eritrea]] that may amount to [[crimes against humanity]].<ref name="NYT_torture_widespread">{{Cite news |date=8 June 2015 |title=Torture and Other Rights Abuses Are Widespread in Eritrea, U.N. Panel Says |work=[[The New York Times]] |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/09/world/africa/eritrea-human-rights-abuses-afwerki-un-probe-crimes-against-humanity-committed.html?_r=0 |access-date=30 March 2019 |quote=has imposed a reign of fear through systematic and extreme abuses of the population that may amount to crimes against humanity}}</ref> [[Amnesty International]] believes that the government of President Isaias Afwerki has imprisoned at least 10,000 political prisoners. Amnesty also claims that torture—for punishment, interrogation and coercion—is widespread.<ref name="Amnesty_rampant_repression">[https://www.amnesty.org/en/articles/news/2013/05/eritrea-rampant-repression-years-after-independence/ "Eritrea: Rampant repression 20 years after independence"], ''[[Amnesty International]]'', London, 9 May 2013. Retrieved on 30 March 2019.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Asmara,_banca_dell'eritrea.JPG|alt=Ornate, two-story red-brick building|thumb|The [[Bank of Eritrea]] in 2005]] |

|||

In 2009, Isaias advocated for the development of indigenous political and economic institutions, and a strategy that suited Eritrea's internal conditions and available resources.<ref name="reuters">{{Cite web |date=21 October 2009 |title=FACTBOX - Key quotes from Eritrean president |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLL474000 |website=Reuters |access-date=8 December 2018 |archive-date=9 December 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181209124353/https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSLL474000 |url-status=live }}</ref> The key elements were to include ambitious infrastructure development campaigns both in terms of power, transport, and telecommunications, as well as with basic healthcare and educational facilities.<ref>{{Cite web |title=TimesInterview with Eritrea's Isaias Afewerki |url=https://www.ft.com/content/35b8905c-a44b-11de-92d4-00144feabdc0 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221210/https://www.ft.com/content/35b8905c-a44b-11de-92d4-00144feabdc0 |archive-date=10 December 2022 |access-date=7 December 2018 |website=Financial Times}}</ref> |

|||

According to the [[World Bank]], Eritrea's recent growth has been associated with the agricultural (one-third of the economy and 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP)) and mining sectors (20 percent). [[Real gross domestic product|Real GDP]] grew by 12 percent in 2018, but fell 2.7 percent from 2015 to 2018. [[Deflation]] existed from 2016 to 2018 due to a currency change, and continued in 2018 after economic and trade ties with Ethiopia were reestablished.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |title=Overview |url=https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/eritrea/overview |access-date=2022-05-30 |website=World Bank |language=en |archive-date=28 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200628104503/https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/eritrea/overview |url-status=live }}</ref>[[File:VOA interviews Afewerki.JPG|thumb|229x229px|[[Voice of America]]'s Peter Clottey interviews Isaias in New York, 2011]]On 18 May 2012, Isaias said in a [[Voice of America|VOA]] interview that the country's development over two decades of independence was "a success story".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Eritrean President Discusses Path to Development |url=https://www.voanews.com/a/eritrean_president_discusses_path_to_development/727263.html |access-date=2022-05-30 |website=VOA |date=18 May 2012 |language=en |archive-date=25 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211025160636/https://www.voanews.com/a/eritrean_president_discusses_path_to_development/727263.html |url-status=live }}</ref> As a result of regional insecurity in 1998, Eritrea has a strong [[fiscal policy]] caused by a sharp drop in capital spending and reductions in revenue. Fiscal pressures, however, are likely to increase.<ref name=":6" /> |

|||

The [[government of Eritrea]] denies the allegations and in turn accuses Amnesty International of supporting a political agenda of "[[regime change]]".<ref>{{Cite tweet |number=1292190404390068230 |user=tsearaia |title=@amnestyusa For many countries like #Eritrea, @amnesty is a terrorist org hell-bent on destabilizing & destroying n…<!-- full text of tweet that Twitter returned to the bot (excluding links) added by TweetCiteBot. This may be better truncated or may need expanding (TW limits responses to 140 characters) or case changes. --> |date=8 August 2020}}</ref> |

|||

==== Human rights ==== |

|||

Although Isaias criticized other leaders during the African Unity summit in Cairo in 1993 for staying in power too long and rejected a cult of personality, his former comrade Andebrhan Welde Giorgis says Isaias went on to personalise power, and "having personalised power, he abused it to the maximum".<ref name="BBC2018" /> |

|||

{{Main article|Human rights in Eritrea}} |

|||

As of 2013, [[Amnesty International]] reported that the government of Isaias imprisoned at least 10,000 political prisoners. Amnesty also claimed that torture—for punishment, interrogation and coercion—is widespread.<ref name="Amnesty_rampant_repression" /> |

|||

In June 2015, a United Nations panel accused Isaias of leading a [[totalitarian government]] responsible for systematic [[human rights violations]] [[human rights in Eritrea|in Eritrea]] that may amount to [[crimes against humanity]].<ref name="NYT_torture_widespread" /> Norwegian academic [[Kjetil Tronvoll]] said that concentration camps for individuals from opposition groups and labor camps with makeshift facilities (often made from shipping containers) exist.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Plaut |first=Martin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vk8jDgAAQBAJ |title=Understanding Eritrea: Inside Africa's Most Repressive State |date=2016 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-066959-1 |pages=3 |language=en |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=19 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319192135/https://books.google.com/books?id=vk8jDgAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> The government has banned independent newspapers and arrested journalists critical of Isaias since 2001, including [[G-15 (Eritrea)|G-15]]: a group of People's Front for Democracy and Justice officials who appealed for an open election.<ref>{{Cite web |title=500,000 Refugees, 'Slavery-like' Compulsory Service, No National Elections, Border Conflicts & Secret Prisons: 5 Human Rights Crises in Eritrea |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/5-human-rights-crises-in-eritrea/ |access-date=2022-05-28 |website=FRONTLINE |language=en-US |archive-date=24 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230924182014/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/5-human-rights-crises-in-eritrea/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Eritrea is closed to human-rights organizations, who are forced to obtain information from [[émigré]]s.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-04-27 |title=Human Rights Situation in Eritrea |url=https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/04/27/human-rights-situation-eritrea |access-date=2022-05-28 |website=Human Rights Watch |language=en |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017141220/https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/04/27/human-rights-situation-eritrea |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The government has been accused of [[enforced disappearance]]s; torture; arbitrary detention, censorship; libel; human trafficking; criminalizing [[LGBT rights in Eritrea|same-sex activity]]; arbitrary and unlawful violations of privacy, judicial independence, freedom of speech, association, movement and [[Religion in Eritrea|religion]]; and forced labor (including national service [[Conscription in Eritrea|past the 18-month legal obligation]]). An August 2015 [[Human Rights Watch]] (HRW) report documented the use of unlawful force (torture and battery) by security authorities against prisoners, national service evaders, army deserters, asylum seekers without travel documents, and religious groups. In June 2018, a thirty-year-old man reportedly died as a result of torture and delayed medical treatment. He was arrested while attending the burial that March of Hajji Musa Mohammed Nur, director of an Islamic school.<ref>{{Cite web |date=28 May 2022 |title=Eritrea 2019 Human Rights Report |url=https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ERITREA-2019-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=20 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240520022245/https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ERITREA-2019-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Freedom in the World]] rated Eritrea "not free" in 2022; the country scored one out of 40 for [[political rights]] and two out of 60 for [[civil liberties]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Eritrea: Freedom in the World 2022 Country Report |url=https://freedomhouse.org/country/eritrea/freedom-world/2022 |access-date=2022-05-30 |website=Freedom House |language=en |archive-date=2 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231002165328/https://freedomhouse.org/country/eritrea/freedom-world/2022 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Foreign relations === |

|||

{{main article|Foreign relations of Eritrea}} |

|||

==== Ethiopia ==== |

|||

{{Main article|Eritrea–Ethiopia relations}} |

|||

{{See also|Eritrean–Ethiopian War|Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict|Eritrean involvement in the Tigray war}}During the [[Ethiopian Civil War]], the [[Tigray People's Liberation Front]] (TPLF) was initially inspired by the Eritreans and received assistance for their independence. By the 1980s and 1990s, the TPLF emerged as a powerful rebel group that increased its military skills in the revolutionary struggle. The groups disagreed and broke up in 1985.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Young |first=John |date=1996 |title=The Tigray and Eritrean Peoples Liberation Fronts: A History of Tensions and Pragmatism |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/161740 |journal=The Journal of Modern African Studies |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=105–120 |doi=10.1017/S0022278X00055221 |issn=0022-278X |jstor=161740 |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017141556/https://www.jstor.org/stable/161740 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Relics_of_War_on_Dahlak_Island.jpg|alt=A destroyed rocket launcher|thumb|Destroyed [[BM-21 Grad]], a relic of the [[Eritrean–Ethiopian War]] (1998–2000)]] |

|||

Eritrea has engaged in border conflicts since its independence, most notably a [[Eritrean–Ethiopian War|war between 1998 and 2000]]. The war began after Eritrea invaded Ethiopia over the disputed border of [[Badme]] on 6 May 1998, and resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths within two years.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2018-07-08 |title=Ethiopia-Eritrea border: Landmark summit aims to end conflict |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44756371 |access-date=2022-05-30 |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017140808/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-44756371 |url-status=live }}</ref> On 12 December 2000, Eritrea signed the [[Algiers Agreement (2000)|Algiers Agreement]] to end the war; however, the countries remained in a "no-war-no-peace" stalemate. Eritrea has security concerns about Ethiopia, particularly its support of weak, splintered Eritrean opposition groups. Isaias uses the disputed border to maintain a war footing and justify indefinite mass mobilization and repression. Eritrea supported Ethiopian rebel groups such as the [[Oromo Liberation Front]] (OLF) and the [[Ogaden National Liberation Front]] (ONLF) to undermine regional Ethiopian influence. In [[Somalia]], Eritrea has trained, armed, and financed militias opposed to the Ethiopian government during its [[Transitional Government of Ethiopia|transitional government]]. The UN Monitoring Group on Somalia recommended an embargo against Eritrea, Ethiopia and other states.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=Watch (Organization) |first=Human Rights |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P3zIY60yiYAC&q=isaias+afwerki+government |title=Service for Life: State Repression and Indefinite Conscription in Eritrea |date=2009 |publisher=Human Rights Watch |isbn=978-1-56432-472-6 |language=en |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=20 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240520022243/https://books.google.com/books?id=P3zIY60yiYAC&q=isaias+afwerki+government#v=snippet&q=isaias%20afwerki%20government&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In late 2008, the relationship between the countries was deemed strained; the Ethiopian Border Commission (EEBC) did not outline the border in November 2007. The United Nations Missions in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) ended in 2008, and Eritrean troops briefly occupied the Temporary Security Zone. Ethiopia remained in control of the EEBC's border inside Eritrea and reached Badme, triggering mass mobilization and high troop concentrations in the area.<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal |last=Lyons |first=Terrence |date=2009 |title=The Ethiopia-Eritrea Conflict and the Search for Peace in the Horn of Africa |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/27756259 |journal=Review of African Political Economy |volume=36 |issue=120 |pages=167–180 |doi=10.1080/03056240903068053 |issn=0305-6244 |jstor=27756259 |s2cid=154642333 |hdl=10.1080/03056240903068053 |hdl-access=free |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=10 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231010083714/https://www.jstor.org/stable/27756259 |url-status=live }}</ref> Eritrea's unchanged stance reinforced the EEBC'S decision, which was backed by international law; Ethiopia remained in ''de facto'' compliance and had strong relations with the UN.<ref name=":5" />[[File:Abiy Ahmed and Isaias Afwerki speaking in Eritrea 2019.jpg|thumb|225x225px|Ethiopian prime minister [[Abiy Ahmed]] with Isaias in March 2019]]In 2018, Isaias oversaw an unexpected transformation of Eritrea's relations with Ethiopia. The 20-year stalemate ended after Ethiopian [[Prime Minister of Ethiopia|Prime Minister]] [[Abiy Ahmed]] came to power in 2018. Abiy signed a "joint declaration of peace and friendship" at a bilateral [[2018 Eritrea–Ethiopia summit|summit]] on 9 July, restoring diplomatic and trade ties with Eritrea.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2020-12-28 |title=Tigray crisis: Eritrea's role in Ethiopian conflict |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55295650 |access-date=2022-05-30 |archive-date=28 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201228004936/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55295650 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="britannica" /> The agreement includes reopening [[Bure (disputed zone)|Burre]] to access the landlocked Ethiopian Port of Eritrea and [[Zalambessa]] for trade, and access to [[Ethio telecom]] and [[Ethiopian Airlines]].<ref>{{Cite news |date=2018-09-11 |title=Ethiopia-Eritrea border reopens after 20 years |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45475876 |access-date=2022-05-30 |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017140434/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45475876 |url-status=live }}</ref> On 16 September, Abiy signed another peace treaty with Isaias in [[Jeddah]]. Saudi Foreign Minister [[Adel al-Jubeir]] tweeted that the agreement "will contribute to strengthening security and stability in the region at large".<ref>{{Cite news |date=2018-09-16 |title=Ethiopian, Eritrean leaders sign peace agreement in Jeddah |language=en |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-eritrea-saudi-idUSKCN1LW0KV |access-date=2022-05-30 |archive-date=5 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230905184207/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-ethiopia-eritrea-saudi-idUSKCN1LW0KV |url-status=live }}</ref> This was widely acknowledged by numerous world leaders, with the [[UAE Government]] awarding Isaias the [[Order of Zayed]] (First Class) in recognition of his efforts to end the conflict.<ref>{{Cite web |date=24 July 2018 |title=UAE President awards Order of Zayed to Eritrean President, Ethiopian Prime Minister |url=http://wam.ae/en/details/1395302700507 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211229132551/http://wam.ae/en/details/1395302700507 |archive-date=29 December 2021 |access-date=8 December 2018 |agency=Emirates News Agency}}</ref> |

|||

After July 2018, the [[List of intelligence agencies#Ethiopia|Ethiopian]] and [[List of intelligence agencies#Eritrea|Eritrean intelligence agencies]] started a close cooperation. This worried Eritrean refugees in [[Addis Ababa]], some of whom were temporarily detained for three weeks, acquitted by Ethiopian courts, and only released two weeks after their acquittal.<ref name="Awate_Eritreans_in_ET_fear" /> |

|||

The [[Tigray war]] began on 3 November 2020 after the [[Tigray People's Liberation Front]], the former ruling party in Ethiopia, attacked the Northern Command center camps of the [[Ethiopian National Defense Force]] (ENDF) in Tigray and pushed them to Eritrea. The [[Eritrean Defence Forces]] joined hands with the ENDF and allegedly with the help of UAE armed drones counter-attacked the TPLF forces. There was alleged [[looting]] in [[Tigray Region]], including systematic, wide-scale looting in [[Axum]] following the [[Axum massacre]] in late November 2020.<ref>{{Cite web |date=26 February 2021 |title=The massacre in Axum |url=https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210226160802/https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AFR2537302021ENGLISH.PDF |archive-date=26 February 2021 |access-date=27 February 2021 |publisher=[[Amnesty International]]}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Tigray crisis: Eritrea's role in Ethiopian conflict |date=28 December 2020 |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55295650 |work=BBC News |access-date=28 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201228004936/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55295650 |url-status=live |archive-date=28 December 2020}}</ref> After several weeks of Ethiopian government denial of the presence of Eritrean troops in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Prime Minister admitted to the presence of Eritrean troops in Ethiopia and agreed to withdraw them. Under international pressure, on 26 March 2021, after a meeting between Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and Isaias, it was announced that Eritrean troops would withdraw from the [[Tigray Region]].<ref>{{Cite news |last=AP and AFP |date=26 March 2021 |title=Ethiopian PM: Eritrean troops to leave Tigray |publisher=[[Deutsche Welle]] |url=https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopian-pm-eritrean-troops-to-leave-tigray/a-57009807 |url-status=live |access-date=26 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220928063037/https://www.dw.com/en/ethiopian-pm-eritrean-troops-to-leave-tigray/a-57009807 |archive-date=28 September 2022}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=26 February 2021 |title=Ethiopia: Eritrean troops' massacre of hundreds of Axum civilians may amount to crime against humanity |publisher=Amnesty International |url=https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity/ |url-status=live |access-date=5 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210405210609/https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2021/02/ethiopia-eritrean-troops-massacre-of-hundreds-of-axum-civilians-may-amount-to-crime-against-humanity/ |archive-date=5 April 2021 |quote=On 19 November 2020, Ethiopian and Eritrean military forces took control of Axum in a large-scale offensive, killing and displacing civilians with indiscriminate shelling and shooting. In the nine days that followed, the Eritrean military engaged in widespread looting of civilian property and extrajudicial executions. Witnesses could easily identify the Eritrean forces. They drove vehicles with Eritrean license plates, wore distinctive camouflage and footwear used by the Eritrean army and spoke Arabic or a dialect of Tigrinya not spoken in Ethiopia. Some bore the ritual facial scars of the Ben Amir, an ethnic group absent from Ethiopia. Finally, some of the soldiers made no secret of their identity; they openly told residents they were Eritrean.}}</ref> |

|||

==== Sudan ==== |

|||

{{main article|Eritrea–Sudan relations}} |

|||

Relations between Eritrea and [[Sudan]] were initially hostile; shortly after independence in 1993, Eritrea charged Sudan with supporting the activities of [[Eritrean Islamic Jihad]], which carried out attacks against the Eritrean government.<ref name="loc20152">{{Cite encyclopedia |title="Ethiopia and Eritrea" |encyclopedia=Sudan: a country study |publisher=[[Federal Research Division]], [[Library of Congress]] |location=Washington, D.C. |url=https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/pdf/CS_Sudan.pdf |last=Shinn |first=David H. |date=2015 |editor-last=Berry |editor1-first=LaVerle |edition=5th |pages=280–282 |isbn=978-0-8444-0750-0 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150920183324/https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/pdf/CS_Sudan.pdf |archive-date=20 September 2015}}</ref> Eritrea broke relations with Sudan at the end of 1994, became a strong supporter of the [[Sudan People's Liberation Movement]]/[[Sudan People's Liberation Army]] (SPLA), and permitted the opposition [[National Democratic Alliance (Sudan)|National Democratic Alliance]] to locate its headquarters in the former Sudan embassy in Asmara.<ref name="loc20152" /> |

|||

Relations were later reestablished in December 2005.<ref>{{cite web |date=10 December 2005 |title=Sudan, Eritrea resume severed diplomatic relations |url=http://www.arabicnews.com/ansub/Daily/Day/051210/2005121017.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070116142921/http://www.arabicnews.com/ansub/Daily/Day/051210/2005121017.html |archive-date=16 January 2007 |website=ArabicNews.com}}</ref> A year later, Isaias and Sudanese president [[Omar al-Bashir]] met for the first time since 2001 in [[Khartoum]].<ref name=":2" /> Isaias later described relations with Sudan as resting on solid ground and having "bright prospects."<ref name="loc20152" /> Eritrea played a prominent role in brokering a peace agreement between the [[Sudanese government]] and [[Eastern Front (Sudan)|Sudan's Eastern Front]].<ref name="loc20152" /><ref>{{cite web |date=2006-04-18 |title=Sudan demands Eritrean mediation with eastern Sudan rebels |url=http://www.sudantribune.com/article.php3?id_article=15117 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060519014705/http://www.sudantribune.com/article.php3?id_article=15117 |archive-date=2006-05-19 |access-date=2006-06-07 |publisher=Sudan Tribune}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=2005-11-04 |title=Turabi terms USA "world's ignoramuses", fears Sudan's partition |url=http://www.sudantribune.com/article.php3?id_article=12393 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060718155147/http://www.sudantribune.com/article.php3?id_article=12393 |archive-date=2006-07-18 |access-date=2006-06-07 |publisher=Sudan Tribune}}</ref> |

|||

On 10 May 2014, the state-owned [[Sudan News Agency]] announced during Isaias' visit to the Al Jeili oil refinery that Sudan had agreed to supply Eritrea with fuel and boost its economic partnership. It was also reported that the Sudanese Electricity Company planned to supply a {{convert|45|km|adj=on}} power line from [[Kassala]] to the Eritrean town of [[Teseney]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Relations between Eritrea and Sudan continue to improve |url=http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1931813577&Country=Eritrea&topic=Politics&subtopic=_5 |access-date=2022-05-29 |website=country.eiu.com |archive-date=5 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230905221237/http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=1931813577&Country=Eritrea&topic=Politics&subtopic=_5 |url-status=live }}</ref> On 4 May 2021, Isaias visited Khartoum to discuss the ongoing border dispute between Ethiopia and Sudan. In conversation with [[Abdel Fattah al-Burhan|Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan]], head of Sudan's [[Transitional Sovereignty Council]], he raised regional issues and the long-time dispute over the [[Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Eritrea's president visits Sudan amid tensions over Ethiopia |url=https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-middle-east-sudan-africa-eritrea-579397fa054363da35a1e04f334f1efb |access-date=2022-05-29 |website=AP NEWS |date=4 May 2021 |language=en |archive-date=20 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240520022244/https://apnews.com/article/ethiopia-middle-east-sudan-africa-eritrea-579397fa054363da35a1e04f334f1efb |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==== Djibouti ==== |

|||

{{Main|Djibouti–Eritrea relations}} |

|||

{{See also|Djiboutian–Eritrean border conflict}} |

|||

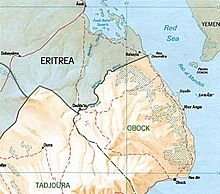

[[File:Djibouti-Eritrea_border_map.jpg|alt=See caption|thumb|Shaded relief map of Djibouti. The original map is from 1991, with the border between Ethiopia and Eritrea added in 2006.]] |

|||

Relations between Eritrea and [[Djibouti]] date back to 1991. The countries waged war in April 1996 when Djibouti accused Eritrea of shelling [[Ras Doumeira]], a small village bounded by Ethiopia's [[Afar Region]]. Eritrea was also accused of redrawing the map of the area. Eritrea denied both claims. The conflict worsened until May 1996, when Eritrean forces retreated from the area and Djibouti retracted the allegations. The Eritrean–Ethiopian War was a threat to and an opportunity for Djibouti. Ethiopia diverted trade through Djibouti via Eritrean ports, strengthening economic ties in accordance with the 1996 protocol. In 1999, Djibouti and Ethiopia signed a military cooperation agreement.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web |date=29 May 2022 |title=The Eritrea-Djibouti border dispute |url=https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/SITREP150908.PDF |access-date=9 October 2023 |archive-date=11 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180211134348/https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/SITREP150908.PDF |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

In 1998, Eritrea accused Djibouti of using its port to supply military equipment to Ethiopia. In June of that year, Djibouti deployed military force in the north to avoid an incursion during the war; French troops were involved with their Djiboutian counterparts. In 1999, France sent two frigates to guard against any approaches toward Ethiopia and Eritrea. Djiboutian President [[Hassan Gouled Aptidon]]'s November 1998 attempt to mediate the Eritrean–Ethiopian War during the [[Organisation of African Unity|Organization of African Unity]] (OAU) summit was rejected by Eritrea for perceived partiality. Djibouti expelled its Eritrean ambassadors and Tekest Ghebrai, an Eritrean national and the former executive secretary of the [[Intergovernmental Authority on Development]] (IGAD), was dismissed.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

The December 1997 treaty was deemed too weak. Eritrea accused Djibouti of siding with Ethiopia in 1999, and Djibouti accused Eritrea of supporting Djiboutian rebel groups in the Ras Doumeira area; Eritrea denied this. Rapprochement between the countries returned in March 2000, after mediation by [[Libya]]. Isaias visited Djibouti in 2001, and President [[Ismaïl Omar Guelleh]] visited Eritrea. This visit created a joint cooperative commission which would conduct an annual review. Guelleh sought a friendly relationship with Eritrea, despite their military imbalance.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

Guelleh visited the disputed area on 22 April 2008, and the Djiboutian Foreign Ministry said that the Eritrean position lay several kilometers inside Djiboutian territory. Eritrea denied an accusation that its soldiers had dug trenches, and military officials met two days later to compare the border map. Djibouti sent troops to the area. Guelleh said on 9 May that the "two armies are facing each other"; the situation was explosive, with hostile forces ready to dismantle Djiboutian sovereignty. With reported [[Qatar]]i mediation, both sides agreed to resolve the confrontation by negotiation.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

==== Somalia ==== |

|||

In July 2018, Eritrea and [[Somalia]] established diplomatic relations. On 28 July, Somalian president [[Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed]] began a three-day visit with Isaias in Asmara during which Somalia expressed solidarity with Eritrea in diplomacy and international politics.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-07-31 |title=For the first time in history, Somalia and Eritrea build a bilateral diplomatic relationship |url=https://thetimesofafrica.com/first-time-history-somalia-eritrea-build-bilateral-diplomatic-relationship/ |access-date=2022-05-30 |website=THE TIMES OF AFRICA |language=en-US |archive-date=17 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017140809/https://thetimesofafrica.com/first-time-history-somalia-eritrea-build-bilateral-diplomatic-relationship/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==== Russia ==== |

|||

{{Main|Eritrea–Russia relations}} |

|||

[[File:Vladimir Putin and Isaias Afwerki (2023-05-31).jpg|thumb|Isaias Afwerki with Russian President [[Vladimir Putin]] at the Kremlin in [[Moscow]] on 31 May 2023]]Along with Belarus, Syria, and North Korea, Eritrea was one of only four countries not including [[Russia]] to vote against a [[Eleventh emergency special session of the United Nations General Assembly|United Nations General Assembly resolution]] condemning Russia's [[Russian invasion of Ukraine|invasion of Ukraine]] in 2022.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.npr.org/2022/03/02/1083872077/u-n-set-to-hold-vote-that-would-demand-russia-end-war-in-ukraine|title=The U.N. approves a resolution demanding that Russia end the invasion of Ukraine|work=NPR|first=Peter|last=Granitz|date=2 March 2022|access-date=3 September 2023|archive-date=23 August 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230823170130/https://www.npr.org/2022/03/02/1083872077/u-n-set-to-hold-vote-that-would-demand-russia-end-war-in-ukraine|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-04-11 |title=Eritrea: Isaias' hostility to the West is about survivalism |url=https://www.theafricareport.com/192505/eritrea-isaias-hostility-to-the-west-is-about-survivalism/ |access-date=2022-05-28 |website=The Africa Report.com |language=en-US |archive-date=20 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240520022246/https://www.theafricareport.com/192505/eritrea-isaias-hostility-to-the-west-is-about-survivalism/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In July 2023, Isaias attended the [[2023 Russia–Africa Summit|Russia–Africa Summit]] in Saint Petersburg and met with Russian President [[Vladimir Putin]]. During the meeting with Putin, Isaias openly denied the existence of a war between Russia and [[Ukraine]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-07-29 |title=Eritrean, Burkina Faso leaders align with Russia, deny Putin's terrorist war |url=https://tvpworld.com/71644604/eritrean-burkina-faso-leaders-align-with-russia-deny-putins-terrorist-war |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230729225316/https://tvpworld.com/71644604/eritrean-burkina-faso-leaders-align-with-russia-deny-putins-terrorist-war |archive-date=2023-07-29 |website=[[TVP World]]}}</ref> |

|||

=== Forto incident === |

|||

{{Main|2013 Eritrean Army mutiny}} |

|||

About 100 soldiers broke into [[Forto]], the building housing the information-ministry correspondent for state television Eri-TV, on 21 January 2013 and surrounded the staff. They forced station director Asmelash Abraha to read a demand to release all prisoners of conscience and political prisoners and to implement the 1997 constitution. After he read two sentences, the station went off the air. Isaias' bodyguards were urged{{by whom?|date=October 2024}} to protect him, his palace, and his airport. Eri-TV returned to the air at 10 a.m. to report a snowstorm in Paris. The mutiny subsided after the government negotiated the release of the ministry's employees.<ref>{{Cite report |title=The Beginning of the End for President Isaias Afwerki? |author=International Crisis Group |pages=Page 3–Page 9 |jstor=resrep31952.6 |journal=Eritrea |year=2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

In the summer of 1981, Isaias met his wife, former [[Eritrean People's Liberation Front|EPLF]] fighter Saba Haile, in a village called [[Nakfa, Eritrea|Nakfa]]. As of 2010 they had three children: Abraham, Elsa, and Berhane.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |year=2010 |title=Biography of Isaias Afwerki |url=http://www.madote.com/2010/11/president-isaias-afwerkis-biography.html |publisher=Madote |access-date=9 December 2010 |archive-date=16 November 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101116013742/http://www.madote.com/2010/11/president-isaias-afwerkis-biography.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>Hillary Rodham Clinton (2003), Oxford Dictionary of African Biography. Simon & Schuster, {{ISBN|0743222253}}.</ref><ref>Michela Wrong (2005), I Didn't Do it for You: How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation. Fourth Estate, {{ISBN|9780007150960}}.</ref> |

|||

Shortly before [[Eritrea]] declared independence, Isaias contracted [[Malaria|cerebral malaria]] and was flown to [[Israel]] for treatment.<ref>{{Cite news |date=12 June 2019 |title=Eritrea's 'ice bucket' bid to oust Isaias Afwerki |work=BBC News |first=Teklemariam |last=Bekit |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48034365 |access-date=30 November 2020 |archive-date=11 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201211131540/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-48034365 |url-status=live }}</ref> Arriving in a coma, he was treated at [[Sheba Medical Center]], where he recovered after successful treatment.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Melman |first=Yossi |date=20 November 2020 |title=Israel, help us overthrow this autocratic regime] |work=[[Haaretz]] |url=https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-please-help-us-overthrow-eritrea-s-autocratic-regime-1.9317083 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20210118032937/https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-israel-please-help-us-overthrow-eritrea-s-autocratic-regime-1.9317083 |archive-date=18 January 2021}}</ref> As of 2019, he was a member of the [[Eritrean Orthodox Church]], one of the four legal churches in [[Eritrea]].<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=Eritrea: A country with several restrictions to freedom of religion or belief |url=https://www.ippforb.com/newsroom/2019/06/27eritrea-a-country-with-several-restrictions-to-freedom-of-religion-or-belief |access-date=2022-06-10 |website=IPPFORB |date=27 June 2019 |language=en-US |quote=The Eritrean government officially recognizes only four religions: the Eritrean Orthodox Church, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church of Eritrea. |archive-date=5 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220605150001/https://www.ippforb.com/newsroom/2019/06/27eritrea-a-country-with-several-restrictions-to-freedom-of-religion-or-belief |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

His nickname "Isu" was frequently used in conversation, and to refer to Isaias in his political capacity, and has appeared in news articles as well.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Isu-virus Demands the Eritrean Pro-Justice Movement to Forge Alliance With The Regional (YES-SEDS) Diaspora Communities |url=https://archive.assenna.com/isu-virus-demands-the-eritrean-pro-justice-movement-to-forge-alliance-with-the-regional-yes-seds-diaspora-communities/ |access-date=5 October 2021 |publisher=Assena |archive-date=19 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211019081644/https://archive.assenna.com/isu-virus-demands-the-eritrean-pro-justice-movement-to-forge-alliance-with-the-regional-yes-seds-diaspora-communities/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=29 January 2021 |title=The war in Tigray: Abiy, Isaias, and the Amhara elite |url=https://www.theafricareport.com/62232/the-war-in-tigray-abiy-isaias-and-the-amhara-elite/#:~:text=In%20the%20Millennium%20Hall%2C%20thousands%20of%20Addis%20Ababa%20elites%20gathered%20to%20give%20Isaias%20the%20reception%20of%20his%20life%2C%20with%20thunderous%20cries%20of%20%E2%80%9CIsu!%20Isu!%E2%80%9D%20resonating%20in%20the%20hall |access-date=5 October 2021 |publisher=The Africa Report |archive-date=19 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211019061448/https://www.theafricareport.com/62232/the-war-in-tigray-abiy-isaias-and-the-amhara-elite/#:~:text=In%20the%20Millennium%20Hall%2C%20thousands%20of%20Addis%20Ababa%20elites%20gathered%20to%20give%20Isaias%20the%20reception%20of%20his%20life%2C%20with%20thunderous%20cries%20of%20%E2%80%9CIsu!%20Isu!%E2%80%9D%20resonating%20in%20the%20hall |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

His training in China made him a great admirer of [[Mao Zedong]], but he reportedly hates [[Deng Xiaoping]].<ref>{{cite web |title=ISAIAS ZEDONG? |date=23 June 2011 |url=https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/8mepr/20102009-isaias-zedong |publisher=Aftenposten |access-date=30 September 2023 |archive-date=3 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231003025050/https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/8mepr/20102009-isaias-zedong |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Temperament === |

|||