Shamanic music: Difference between revisions

m copy editing, encyclopedise |

Adjustment of words |

||

| (36 intermediate revisions by 22 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Ritualistic music genre}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=March 2022}} |

|||

{{Multiple issues| |

{{Multiple issues| |

||

{{essay-like|date=July 2012}} |

{{essay-like|date=July 2012}} |

||

{{tone|date=July 2012}} |

{{tone|date=July 2012}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

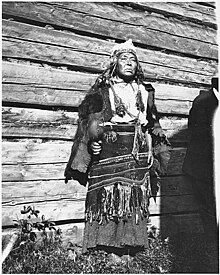

[[File:Gitksan man.jpg|thumb|right|Gitksan shaman with rattle]] |

|||

'''Shamanic music''' is music played either by actual shamans as part of their rituals, or by people who, whilst not themselves shamans, wish to evoke the cultural background of [[shamanism]] in some way. Therefore, '''Shamanic music''' includes both music used as part of shamans' rituals and music that refers to, or draws on, this. |

|||

'''Shamanic music''' is ritualistic music used in religious and spiritual ceremonies associated with the practice of [[shamanism]]. Shamanic music makes use of various means of producing music, with an emphasis on voice and rhythm. It can vary based on cultural, geographic, and religious influences. |

|||

Recently in [[Indigenous peoples of Siberia|Siberia]], music groups drawing on |

Recently in [[Indigenous peoples of Siberia|Siberia]], music groups drawing on knowledge of shamanic culture have emerged. In the West, shamanism has served as an imagined background to music meant to [[altered state of consciousness|alter a listener's state of mind]]. [[Culture of Korea|Korea]] and [[Tibetan culture|Tibet]] are two cultures where the music of shamanic rituals has interacted closely with other traditions. |

||

In shamanism, the shaman has a more active musical role than the medium in [[spirit possession]]. |

|||

[[Culture of Korea|Korea]] and [[Tibetan culture|Tibet]] are two cultures where the music of shamanic ritual has interacted closely with other traditions. |

|||

[[File:Gitksan man.jpg|thumb|right|Gitksan shaman with rattle]] |

|||

== Shamanic and musical performance == |

== Shamanic and musical performance == |

||

Since a Shamanic ritual includes a spiritual purpose and motive, it cannot be regarded as a musical performance, even though shamans use music (singing, drumming, and other instruments) in their rituals. Several things follow the ritual. First, a shamanic ritual performance is, above all, a series of actions and not a series of musical sounds.<ref>Mihály Hoppál, ''Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies'', in Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'', Istor Budapest 1997 p 129 "...the struggle with the harmful spirits during which great drumbeats indicated that the shaman had driven a "steel arrow" for each beat into the spirits of sickness."</ref> Second, the shaman's attention is directed inwards towards her or his visualization of the spirit world and communication with the spirits, and not outwards to any listeners who might be present.<ref>Tim Hodgkinson, ''Musicians, Carvers, Shamans'', Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006) p 9."Sergei Tumat (a Tuvan shaman who had previously studied music): "When I shamanize, I'm not here, not in the place where I'm playing the dungur drum, it's just my material body that's there: I'm away with the spirits, that's where my total attention is. If someone touches me, tries to get my attention there in the yurt, that's dangerous, it would be like falling a long way: so it's completely different from playing music to an audience, where you have to be there, to be attentive to what your material body is doing, to everything I learned in music school...""</ref> Third, it is important for the success of the ritual that it be given its own clearly defined context that is quite different from any kind of entertainment. Fourth, any theatrical elements that are added to impress an audience are of a type to make the contact with the spirits seem more real and not to suggest the performer's musical virtuosity. From a musical perspective, shamanic ritual performances have the distinctive feature of {{wt|en|discontinuity}}. Breaks may happen because a spirit is proving difficult to communicate with, or the shaman needs to call a different spirit. Typically, phases of the performance are broken off abruptly, perhaps to be restarted after a gap, perhaps not.<ref>Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001, p135-6</ref><ref>Ronald Hutton, ''The Shamans of Siberia'', Isle of Avalon Press, 1993, p29 and p31</ref><ref>Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235-7</ref> The rhythmic dimension of the music of shamans' rituals has been connected to the idea of both incorporating the rhythms of nature and magically re-articulating them.<ref>Carlo Serra, (in Italian)''Ritmo e ciclità nella cultura sciamanica'', in Antonello Colimberti (ed) ''Musiche e sciamani'', Textus, Milan 2000, p67</ref> |

|||

Although shamans use singing as well as drumming and sometimes other instruments, a shamanic ritual is not a musical performance in the normal sense, as it includes a fundamental spiritual motive and function. Several things follow from this. First, a shamanic ritual performance is, above all, a series of actions and not a series of musical sounds.<ref>Mihály Hoppál, ''Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies'', in Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'', Istor Budapest 1997 p 129 "...the struggle with the harmful spirits during which great drumbeats indicated that the shaman had driven a "steel arrow" for each beat into the spirits of sickness."</ref> Second, the shaman's attention is directed inwards towards her or his visualisation of the spirit world and communication with the spirits, and not outwards to any listeners who might be present.<ref>Tim Hodgkinson, ''Musicians, Carvers, Shamans'', Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006) p 9."Sergei Tumat (a Tuvan shaman who had previously studied music): "When I shamanize, I'm not here, not in the place where I'm playing the dungur drum, it's just my material body that's there: I'm away with the spirits, that's where my total attention is. If someone touches me, tries to get my attention there in the yurt, that's dangerous, it would be like falling a long way: so it's completely different from playing music to an audience, where you have to be there, to be attentive to what your material body is doing, to everything I learned in music school...""</ref> Third, it is important for the success of the ritual that it be given its own clearly defined context that is quite different from any kind of entertainment. Fourth, any theatrical elements that are added to impress an audience are of a type to make the contact with the spirits seem more real and not to suggest the performer's musical virtuosity. From a musical perspective shamanic ritual performances have the distinctive feature of {{wt|en|discontinuity}}. Breaks may happen because a spirit is proving difficult to communicate with, or the shaman needs to call a different spirit. Typically, phases of the performance are broken off abruptly, perhaps to be restarted after a gap, perhaps not.<ref>Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001, p135-6</ref><ref>Ronald Hutton, ''The Shamans of Siberia'', Isle of Avalon Press, 1993, p29 and p31</ref><ref>Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235-7</ref> The rhythmic dimension of the music of shamans' rituals has been connected to the idea of both incorporating the rhythms of nature and magically re-articulating them.<ref>Carlo Serra, (in Italian)''Ritmo e ciclità nella cultura sciamanica'', in Antonello Colimberti (ed) ''Musiche e sciamani'', Textus, Milan 2000, p67</ref> |

|||

== Shamanism and possession == |

== Shamanism and possession == |

||

It has been argued<ref>Gilbert Rouget, ''Music and Trance'', University of Chicago Press 1985 p125</ref> that shamanism and [[spirit possession]] involve contrasting kinds of special states of mind. The shaman actively enters the spirit world, negotiates with her or his helper spirit and then with other spirits as necessary, and moves between different territories of the spirit world. The possessed medium, on the other hand, is the passive recipient of a powerful spirit or god. This reflects the different uses of music involved. Possession music<ref>Fremont E.Besmer, ''Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance''. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983</ref> is typically longer in duration, [[Hypnosis|mesmeric]], loud, and intense, with climaxes of rhythmic intensity and volume to which the medium has learned to respond by entering a trance state: the music is not played by the medium but by one or more musicians. In shamanism, the music is played by the shaman, confirms the shaman's power (in the words of the shaman's song), and is used actively by the shaman to modulate movements and changes of state as part of an active journey within the spirit world. In both cases, the connection between music and an [[altered state of mind]] depends on both psychoacoustic and cultural factors, and the music cannot be said to 'cause' trance-states.<ref>Roberte Hamayon,(in French) ''Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme'', in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995, p155 seq.</ref> |

|||

It has been argued<ref>Gilbert Rouget, ''Music and Trance'', University of Chicago Press 1985 p125</ref> that shamanism and [[spirit possession]] involve contrasting kinds of special states of mind. The shaman actively enters the spirit world, negotiates with her or his own helper spirit and then with other spirits as necessary, and moves between different territories of the spirit world. The possessed medium, on the other hand, is the passive recipient of a powerful spirit or god. This reflects on the different uses of music involved. Possession music<ref>Fremont E.Besmer, ''Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance''. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983</ref> is typically long in duration, [[Hypnosis|mesmeric]], loud and intense, with climaxes of rhythmic intensity and volume to which the medium has learned to respond by entering a trance state: the music is not played by the medium but by one or more musicians. In shamanism, the music is played by the shaman, confirms the shaman's power (in the words of the shaman's song), and is used actively by the shaman to modulate movements and changes of state as part of an active journey within the spirit world. In both cases the connection between music and an [[altered state of mind]] depends on both psychoacoustic and cultural factors, and the music cannot be said to 'cause' trance-states.<ref>Roberte Hamayon,(in French) ''Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme'', in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995, p155 seq.</ref> |

|||

== Use of sounds == |

== Use of sounds == |

||

{{See also|Sound mimesis in various cultures|Imitation of sounds in shamanism}} |

{{See also|Sound mimesis in various cultures|Imitation of sounds in shamanism}} |

||

Sound is tactile; whereas visual information is experienced at the surface, auditory information seems to be both outside and inside the body.<ref>Walter Ong, ''Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word'', Methuen, 1982</ref> [[Sound mimesis in various cultures|In oral cultures in which survival involves close contact with nature, sound often connects inner feelings to features of the natural environment]]. In many cases, this holds also for the [[Imitation of sounds in shamanism|music in shamanistic practice, including e.g. onomatopoeia, imitation of animal cries etc.]] |

Sound is tactile; whereas visual information is experienced at the surface, auditory information seems to be both outside and inside the body.<ref>Walter Ong, ''Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word'', Methuen, 1982</ref> [[Sound mimesis in various cultures|In oral cultures in which survival involves close contact with nature, sound often connects inner feelings to features of the natural environment]]. In many cases, this holds also for the [[Imitation of sounds in shamanism|music in shamanistic practice, including e.g. onomatopoeia, imitation of animal cries etc.]] The shaman's use of sound is to catalyze an imaginary inner environment which is experienced as a sacred space-time in which the shaman travels and encounters spirits. Sound, passing constantly between inner and outer, connects this imaginary space with the actual space of the ritual in which the shaman is moving and making ritual actions and gestures. |

||

It has been suggested that the sound material used by the shaman constitutes a system of sounds.<ref>Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) ''La musica sciamanica'' . |

It has been suggested that the sound material used by the shaman constitutes a system of sounds.<ref>Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) ''La musica sciamanica'' . – Xenia – 2004, p. 2</ref> This idea of [[semiotics]] of the sound material would imply a symbolic language shared between the shaman and the surrounding community. However, the evidence suggests that any symbolic language elements are understood only by the shaman and perhaps by other shamans initiated by this shaman. In other words, the symbolic language, if there is one, is more likely to be shared with the spirits than with a human community.<ref>Michael Taussig, ''The Nervous System'' . – Routledge – 1992 p.177</ref> |

||

A shaman may use different sounds for different ritual purposes: |

A shaman may use different sounds for different ritual purposes: |

||

;Setting up the sound-space of the ritual: A very important element in [[Shamanism in Siberia|Siberian shamanism]] is the use of hanging metallic objects – possibly including small bells – attached to the shaman's ritual cloak and to the inside of the drum and also sometimes to the beater. This sets up a continuously moving sound field, heard as a single complex sound.<ref>Andrew Stiller, ''Handbook of Instrumentation'', University of California Press, 1985, p 121, {{ISBN|0-520-04423-1}}</ref> A further element is the spatialization of sound brought about not only by the shaman's movement but also by techniques of singing into the drum to create the illusion of the voice coming from elsewhere. Different individual shamans and different local traditions may use different sounds. For example, in the south of Tuva and in Mongolia the ''khoums'', or jaw harp is commonly used in shaman sing.<ref>Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001, p124</ref> |

|||

*'''Setting up the sound-space of the ritual''' |

|||

;Preparation: Particular sounds, like bells, may be used for purifying the place in which the ritual is to be performed.<ref>Marilyn Walker, ''Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia'', in |

|||

A very important element in [[Shamanism in Siberia|Siberian shamanism]] is the use of hanging metallic objects - possibly including small bells - attached to the shaman's ritual cloak and to the inside of the drum and also sometimes to the beater. This sets up a continuously moving sound field, heard as a single complex sound.<ref>Andrew Stiller, ''Handbook of Instrumentation'', University of California Press, 1985, p 121, {{ISBN|0-520-04423-1}}</ref> A further element is the spatialisation of sound brought about not only by the shaman's movement, but also by techniques of singing into the drum to create the illusion of the voice coming from elsewhere. Different individual shamans and different local traditions may use different sounds. For example, in the south of Tuva and in Mongolia the ''khomus'', or jaw harp is commonly used in shamanising.<ref>Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001, p124</ref> |

|||

*'''Preparation''' |

|||

Particular sounds, like bells, may be used for purifying the place in which the ritual is to be performed.<ref>Marilyn Walker, ''Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia'', in |

|||

Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p45</ref> This is because a ritual involving contact with the spirits is always potentially dangerous, and one of the dangers is that of pollution. |

Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p45</ref> This is because a ritual involving contact with the spirits is always potentially dangerous, and one of the dangers is that of pollution. |

||

;Calling and sending back spirits: A bell may also be used for calling or sending back spirits.<ref>Maria Kongin Seo, ''Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul'', Routledge 2002 p14</ref> Shamans will also imitate the sounds of birds and animals in order to call spirits.<ref>Theodore Levin, ''Where Rivers and Mountains Sing'', (Indiana University Press 2006)</ref> Sami shamanic singing, called [[Joik]], is also about summoning, for example, animal spirits, rather than singing about them or representing them: the spirit is experienced as being present.<ref>Tina Ramnarine, ''Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik'', Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009, p. 191</ref> |

|||

;Healing: Within shamanic ritual, sound can also be used as a healing power, conceived as a way of directing spiritual energy from the shaman into an afflicted person.<ref>Marilyn Walker, 2003, p46</ref> In [[Tuva]] sick persons are said to have been healed by the sound of a stringed instrument made from a tree struck by lightning. |

|||

*'''Calling and sending back spirits''' |

|||

A bell may also be used for calling or sending back spirits.<ref>Maria Kongin Seo, ''Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul'', Routledge 2002 p14</ref> Shamans will also imitate the sounds of birds and animals in order to call spirits.<ref>Theodore Levin, ''Where Rivers and Mountains Sing'', (Indiana University Press 2006)</ref> Sami shamanic singing, called [[Joik]], is also about summoning, for example, animal spirits, rather than singing about them or representing them: the spirit is experienced as being present.<ref>Tina Ramnarine, ''Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik'', Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009, p. 191</ref> |

|||

*'''Healing''' |

|||

Within shamanic ritual, sound can also be used as a healing power, conceived as a way of directing spiritual energy from the shaman into an afflicted person.<ref>Marilyn Walker, 2003, p46</ref> In [[Tuva]] sick persons are said to have been healed by the sound of a stringed instrument made from a tree struck by lightning. |

|||

== Shaman's song == |

== Shaman's song == |

||

The '''shaman's song''' – or ''largish''<ref>Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'' Istor Budapest 1997</ref> in Tuvan – is personal to the shaman<ref>Mihály Hoppál, ''Studies on Eurasian Shamanism'' in ''Shamans and Cultures'' in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258-288 Istor Budapest 1993</ref> and tells of her or his birthplace, initiation, ancestral pedigree, special gifts, and special connections to particular spirits. The melody and words are composed by the shaman and generally remain the same throughout the shaman's professional life. The ''largish'' is often sung near the beginning of the ritual and accompanied by drumming on the danger drum. It serves to remind the shaman of their shamanic identity and power. It proclaims the shaman's abilities and announces the shaman to the spirits. In some traditions, the shaman's song may be broken up into short sections, varied, and recombined in different performances.<ref>Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235</ref> |

|||

The '''shaman's song''' - or ''algysh'' <ref>Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'' Istor Budapest 1997</ref> in Tuvan - is personal to the shaman<ref>Mihály Hoppál, ''Studies on Eurasian Shamanism'' in ''Shamans and Cultures'' in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258-288 Istor Budapest 1993</ref> and tells of her or his birthplace, initiation, ancestral pedigree, special gifts and special connections to particular spirits. The melody and words are composed by the shaman and generally remain the same throughout the shaman's professional life. The ''algysh'' is often sung near the beginning of the ritual and accompanied by drumming on the dungur drum. It serves to remind the shaman of their shamanic identity and power. It proclaims the shaman's abilities and announces the shaman to the spirits. In some traditions the shaman's song may be broken up into short sections, varied and recombined in different performances.<ref>Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235</ref> |

|||

== Korean shamanic music == |

== Korean shamanic music == |

||

{{See also|Korean shamanism| |

{{See also|Korean shamanism|Musok eumak}} |

||

[[Korea]] is the only country where shamanism appears to have been a state religion practiced by the literate classes, during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC – 668 AD). Under successive dynasties, shamanism was gradually relegated to a popular or folk status with the arrival of [[Confucianism]], [[Taoism]], and [[Buddhism]]. The early official status of shamanism is the probable explanation for the fact that shamanic rituals in Korea developed highly complex and established forms. Correspondingly the music used in shamanic rituals is more elaborate in Korea than elsewhere. Furthermore, since the emergence of Korean contemporary nationalism, there has been a strong and sustained state intervention to preserve artistic traditions.<ref>Keith Howard, ''Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity'' v. 1 (SOAS Musicology Series) 2006</ref> All of these factors make it uniquely difficult in Korea to distinguish the 'pure' from hybrid and concert forms of shamanic ritual music. For example, ''[[Sinawi]]'' is a musical form that can be used in shamanic rituals or accompany folk dances, or for urban concert performances. In the ritual context ''Sinai,'' is often performed by a small ensemble with the ''change'' hour-glass drum and two melodic instruments, often the ''Taegu'' flute and the ''[[Piri (instrument)|piri]]'' oboe. In concert the ensemble is augmented with stringed instruments<ref>Kyo-Chul Chung CD notes for ''Seoul Ensemble of Traditional Music'' World Network 12, WDR 54.039.</ref> Modern ''Sinai'' is played in a minor mode in 12/8 time.<ref>CD notes for''A selection of Korean traditional music, volume 2''. Instrumental Music 2, SBCD-4380-2</ref> The role of music in Korean shamanism seems intermediary between the possession trance model and the Siberian model: in the ''Kut'' ritual, the music, played by musicians, first calls on the god to possess the ''mudang'' (shaman), then accompanies the god during their time in the shaman's body, then sends back and placates the god at the end.<ref>''Shamanism, The Spirit World of Korea'', eds Chai-shin Yu and R.Guisso, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley California 1988</ref> However, the shaman is the singer and dancer and the shaman directs the musicians.<ref>Lee Bo Hyeong CD notes for Kim Suk Chul Ensemble: ''Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard'', JVC, VICG-5261 (1993)</ref> |

|||

== Bön shamanic music and Buddhist music == |

== Bön shamanic music and Buddhist music == |

||

Before Buddhism came to Tibet, the local form of shamanism was '''[[Bön]]'''. Bön developed into an organised religion. When Buddhism arrived, both religions began competing with each other |

Before Buddhism came to Tibet, the local form of shamanism was '''[[Bön]]'''. Bön developed into an organised religion. When Buddhism arrived, both religions began competing with each other and incorporated many of each other's practices. The Bön shaman's drum on a pole became part of Tibetan Buddhist ritual music ensembles. Also, the shang – a kind of bell-cymbal – became incorporated into Buddhist rituals. It was formerly only used by shamans to clear away negative energy before shamanic rituals.<ref>Margaret J. Kartomi ''On concepts and classifications of musical instruments''University of Chicago Press, 1990 pp 75–83 {{ISBN|978-0-226-42549-8}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.frankperry.co.uk/Tibetan%20Bowls.htm |title=The Singing Bowls of Tibet |access-date=2009-03-16 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090216183730/http://frankperry.co.uk/Tibetan%20Bowls.htm |archive-date=2009-02-16 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thepathoflight.it/worken.php |title=The Path of Light |access-date=2009-03-16 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100613215026/http://www.thepathoflight.it/worken.php |archive-date=2010-06-13 }}</ref> |

||

The practice of giving a sonorous identity to deities, of calling them and sending them back by means of sounds, may well have entered Tibetan Buddhist ritual from Bön tradition.<ref>Mireille Helffer (in French)''Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain'' in ''L'Homme 171-2'', Paris 2004 pp |

The practice of giving a sonorous identity to deities, of calling them and sending them back by means of sounds, may well have entered Tibetan Buddhist ritual from Bön tradition.<ref>Mireille Helffer (in French)''Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain'' in ''L'Homme 171-2'', Paris 2004 pp 183–184</ref> |

||

== Adoption by popular music == |

== Adoption by popular music == |

||

From the late 1980s with the loosening up of political restrictions |

From the late 1980s with the loosening up of political restrictions several of Siberian native cultures underwent a cultural renaissance, shamans began to practice openly again, and musicians formed '''bands''' drawing on shamanic traditions. Cholbon<ref>Henri Lecomte,(in French) ''Approches Autochtones du Chamanisme Sibérien au début du XXI Siècle'', in ''Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19'', Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006</ref> and AiTal,<ref>Aimar Ventsel, ''Sakha Pop Music'' p.10 http://www.princeton.edu/~restudy/soyuz_papers/Ventsel.pdf{{dead link|date=March 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> in Sakha/Yakutsk, Biosyntes and early [[Yat-Kha]] in Tuva fall into this category. Nevertheless, the musicians involved, if sometimes unsure of their exact role, recognised an important difference between artists using shamanic themes and shamans themselves. In the West, bands began to apply the label 'shamanic' loosely to any music that might induce a trance state.<ref>Keith Howard, ''Sonic Transformations of Shamanic Representations'' in AHRP Research Centre Newsletter 4, SOAS 2004, p19</ref><ref>Terence McKenna, ''The Archaic revival'' Harper Collins 1991</ref> This was partly due to the rarity of actual recordings of shamans' rituals.<ref>Gilbert Rouget, ''Music and Trance'', University of Chicago Press 1985 p130</ref> Meanwhile, the British-Tuvan group [[K-Space (band)|K-Space]] developed ways of combining improvisation, electronics, and experimental recording and montage techniques with the more shamanic side of Tuvan traditional music. In Hungary [[Galloping Coroners|Vágtázó Halottkémek]]<ref>Kathryn Milun quotes Anna Szemere: ''Up From the Underground – The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary'' Penn State Press 2001, http://www.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces/vol1/milun.html {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090505141555/http://www.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces/vol1/milun.html |date=2009-05-05 }}</ref>(in English: Galloping Coroners) later [[Galloping Wonder Stag|Vágtázó Csodaszarvas]] set out under the banner of shamanpunk to use ethnographic materials as manuals on how to reach and communicate ecstatic states. From 2005 Vágtázó Csodaszarvas (Galloping Wonder Stag) continued Vágtázó Halottkémek music philosophy turning it into a neotraditional music style closer to world music, replacing electronic guitars and drums with acoustic folk instruments. |

||

== Discography == |

== Discography == |

||

[[File:Stepanida Borisova at Khan-Altay psytrance festival.JPG|thumb|Stepanida Borisova is the [[Yakuts|Yakut]] folk singer]] |

[[File:Stepanida Borisova at Khan-Altay psytrance festival.JPG|thumb|Stepanida Borisova is the [[Yakuts|Yakut]] folk singer]] |

||

''Mongolie Chamanes et Lamas'', Ocora C560059 (1994) |

* ''Mongolie Chamanes et Lamas'', Ocora C560059 (1994) |

||

* ''Shamanic and Narrative Songs from the Siberian Arctic'', Sibérie 1, Musique du Monde, BUDA 92564-2 |

|||

* ''Musiche e sciamani'', Musica del Mondo, Textus 001 (2000). Contains tracks assembled from the set of seven CDs of Siberian music on BUDA curated by Henri Lecomte. Sold with book (in Italian) ''Musiche e sciamani'', ed Antonello Colimberti, Textus 2000. |

|||

''Shamanic and Narrative Songs from the Siberian Arctic'', Sibérie 1, Musique du Monde, BUDA 92564-2 |

|||

* Kim Suk Chul / [[Kim Seok Chul]] Ensemble: ''Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard'', JVC, VICG-5261 (1993) |

|||

* ''Trommeln der Schamanen'', Tondokumente der Ausstellung, Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich (2007) |

|||

''Musiche e sciamani'', Musica del Mondo, Textus 001 (2000). Contains tracks assembled from the set of seven CDs of Siberian music on BUDA curated by Henri Lecomte. Sold with book (in Italian) ''Musiche e sciamani'', ed Antonello Colimberti, Textus 2000. |

|||

* ''Tuva, Among the Spirits'', Smithsonian Folkways SFW 40452 (1999) |

|||

* Stepanida Borisova, ''Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (1)'' SOASIS 17 (2008) |

|||

Kim Suk Chul / [[Kim Seok Chul]] Ensemble: ''Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard'', JVC, VICG-5261 (1993) |

|||

* Chyskyyrai, ''Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (2)'' SOASIS 18 (2008) |

|||

* Gendos Chamzyrzn, ''Kamlaniye'', Long Arms (Russia) CDLA 04070 (2004) |

|||

''Trommeln der Schamanen'', Tondokumente der Ausstellung, Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich (2007) |

|||

* ''Tabuk'', Contemporary Sakha Folk Music, Feelee LP (Russia) FL 3018/019 (1991) |

|||

''Tuva, Among the Spirits'', Smithsonian Folkways SFW 40452 (1999 ) |

|||

Stepanida Borisova, ''Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (1)'' SOASIS 17 (2008) |

|||

Chyskyyrai, ''Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (2)'' SOASIS 18 (2008) |

|||

Gendos Chamzyrzn, ''Kamlaniye'', Long Arms (Russia) CDLA 04070 (2004) |

|||

''Tabuk'', Contemporary Sakha Folk Music, Feelee LP (Russia) FL 3018/019 (1991) |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Fremont E.Besmer, ''Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance''. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983 |

*Fremont E.Besmer, ''Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance''. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983 |

||

*Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar, ''Musical Instruments as Paraphernalia of the Shamans in Northern Mongolia'', in ''Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis (New Series)'', ed Gisa Jähnichen, MV-Wissenschaft Verlag, 2017, p 1-32. |

|||

*Antonello Colimberti (ed) (in Italian) ''Musiche e sciamani'', Textus, Milan 2000 |

|||

Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar, ''Musical Instruments as Paraphernalia of the Shamans in Northern Mongolia'', in ''Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis (New Series)'', ed Gisa Jähnichen, MV-Wissenschaft Verlag, 2017, p 1-32. |

|||

*''Shamanism, The Spirit World of Korea'', eds Chai-shin Yu and R.Guisso, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley California 1988 |

|||

*Vilmos Diószegi, ''Tracing Shamans in Siberia'' Anthropological Publications, Netherlands 1968. |

|||

Antonello Colimberti (ed) (in Italian) ''Musiche e sciamani'', Textus, Milan 2000 |

|||

*Roberte Hamayon, (in French) ''Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme'', in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995. |

|||

*Roberte Hamayon, (in French) ''Gestes et Sons, Chamane et Barde'', in ''Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19'', Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006 |

|||

''Shamanism, The Spirit World of Korea'', eds Chai-shin Yu and R.Guisso, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley California 1988 |

|||

*Mireille Helffer (in French) ''Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain'' in ''L'Homme 171-2'', Paris 2004 |

|||

*Tim Hodgkinson, ''Musicians, Carvers, Shamans'', Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006) |

|||

Vilmos Diószegi, ''Tracing Shamans in Siberia'' Anthropological Publications, Netherlands 1968. |

|||

*Tim Hodgkinson, ''Siberian shamanism and improvised music'', Contemporary Music Review vol 14, parts 1–2, Netherlands, Harwood,1996. |

|||

*Mihály Hoppál, ''Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies'', in Mongush Kenin Lopsan ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'', Istor Budapest 1997 |

|||

Roberte Hamayon, (in French) ''Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme'', in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995. |

|||

*Mihály Hoppál, ''Studies on Eurasian Shamanism'' in ''Shamans and Cultures'' in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258–288 Istor Budapest 1993 |

|||

*Keith Howard, ''Sonic Transformations of Shamanic Representations'' in AHRP Research Centre Newsletter 4, SOAS 2004. |

|||

Roberte Hamayon, (in French) ''Gestes et Sons, Chamane et Barde'', in ''Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19'', Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006 |

|||

*Keith Howard, ''Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity'' v. 1 (SOAS Musicology Series) 2006 |

|||

*Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996. |

|||

Mireille Helffer (in French)''Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain'' in ''L'Homme 171-2'', Paris 2004 |

|||

*Ronald Hutton, ''The Shamans of Siberia'', Isle of Avalon Press, 1993 |

|||

*Margaret J. Kartomi, ''On concepts and classifications of musical instruments''University of Chicago Press, 1990 {{ISBN|978-0-226-42549-8}} |

|||

Tim Hodgkinson, ''Musicians, Carvers, Shamans'', Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006) |

|||

*Henri Lecomte, (in French) ''{{lang|fr|Approches Autochtones du Chamanisme Sibérien au début du XXI Siècle}}'', in ''Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19'', Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006 |

|||

*Theodore Levin, ''Where Rivers and Mountains Sing'', Indiana University Press 2006. |

|||

Tim Hodgkinson, ''Siberian shamanism and improvised music'', Contemporary Music Review vol 14, parts 1–2, Netherlands, Harwood,1996. |

|||

*Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'' Istor Budapest 1997 |

|||

*Terence McKenna, ''The Archaic revival'' Harper Collins 1991 |

|||

Mihály Hoppál, ''Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies'', in Mongush Kenin Lopsan ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'', Istor Budapest 1997 |

|||

*Rodney Needham, ''Percussion and Transition'', Man 2:606-14. 1967 |

|||

*Walter Ong, ''Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word'', Methuen, 1982 |

|||

Mihály Hoppál, ''Studies on Eurasian Shamanism'' in ''Shamans and Cultures'' in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258–288 Istor Budapest 1993 |

|||

*Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001. |

|||

*Tina Ramnarine, ''Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik'', Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009 |

|||

Keith Howard, ''Sonic Transformations of Shamanic Representations'' in AHRP Research Centre Newsletter 4, SOAS 2004. |

|||

*Gilbert Rouget, ''Music and Trance'', University of Chicago Press 1985 |

|||

*Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) ''La musica sciamanica'', Xenia 2004 |

|||

Keith Howard, ''Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity'' v. 1 (SOAS Musicology Series) 2006 |

|||

*Maria Kongin Seo, ''Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul'', Routledge 2002 |

|||

*Andrew Stiller, ''Handbook of Instrumentation'', University of California Press, 1985, {{ISBN|0-520-04423-1}} |

|||

Caroline Humphrey, ''Shamans and elders''. Oxford, OUP1996. |

|||

*Anna Szemere ''Up From the Underground – The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary'' Penn State Press 2001 |

|||

*Michael Taussig, ''The Nervous System'', Routledge 1992 |

|||

*Sevyan Vainshtein, ''The Tuvan Shaman's Drum and the ceremony of its Enlivening'', in V.Dioszegi (ed), ''Popular Beliefs and Folklore in Siberia'', Bloomington 1968 |

|||

*Aimar Ventsel, ''Sakha Pop Music'' http://www.princeton.edu/~restudy/soyuz_papers/Ventsel.pdf{{dead link|date=March 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} |

|||

Margaret J. Kartomi, ''On concepts and classifications of musical instruments''University of Chicago Press, 1990 {{ISBN|978-0-226-42549-8}} |

|||

*Marilyn Walker, ''Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia'', in Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p40-48 |

|||

*Damian Walter, ''The Medium of the Message: Shamanism as Localised Practice in the Nepal Himalayas'' in ''The Archaeology of Shamanism'', ed Neil Price, Routledge 2001 |

|||

Henri Lecomte,(in French) ''{{lang|fr|Approches Autochtones du Chamanisme Sibérien au début du XXI Siècle}}'', in ''Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19'', Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006 |

|||

Theodore Levin, ''Where Rivers and Mountains Sing'', Indiana University Press 2006. |

|||

Mongush Kenin Lopsan, ''Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva'' Istor Budapest 1997 |

|||

Terence McKenna, ''The Archaic revival'' Harper Collins 1991 |

|||

Rodney Needham, ''Percussion and Transition'', Man 2:606-14. 1967 |

|||

Walter Ong, ''Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word'', Methuen, 1982 |

|||

Carole Pegg, ''Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative'', University of Washington Press, 2001. |

|||

Tina Ramnarine, ''Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik'', Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009 |

|||

Gilbert Rouget, ''Music and Trance'', University of Chicago Press 1985 |

|||

Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) ''La musica sciamanica'', Xenia 2004 |

|||

Maria Kongin Seo, ''Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul'', Routledge 2002 |

|||

Andrew Stiller, ''Handbook of Instrumentation'', University of California Press, 1985, {{ISBN|0-520-04423-1}} |

|||

Anna Szemere ''Up From the Underground - The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary'' Penn State Press 2001 |

|||

Michael Taussig, ''The Nervous System'', Routledge 1992 |

|||

Sevyan Vainshtein, ''The Tuvan Shaman's Drum and the ceremony of its Enlivening'', in V.Dioszegi (ed), ''Popular Beliefs and Folklore in Siberia'', Bloomington 1968 |

|||

Aimar Ventsel, ''Sakha Pop Music'' http://www.princeton.edu/~restudy/soyuz_papers/Ventsel.pdf{{dead link|date=March 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} |

|||

Marilyn Walker, ''Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia'', in |

|||

Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p40-48 |

|||

Damian Walter, ''The Medium of the Message: Shamanism as Localised Practice in the Nepal Himalayas'' in ''The Archaeology of Shamanism'', ed Neil Price, Routledge 2001 |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

<references/> |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

| Line 162: | Line 108: | ||

* https://web.archive.org/web/20090216183730/http://frankperry.co.uk/Tibetan%20Bowls.htm |

* https://web.archive.org/web/20090216183730/http://frankperry.co.uk/Tibetan%20Bowls.htm |

||

* https://web.archive.org/web/20100613215026/http://www.thepathoflight.it/worken.php |

* https://web.archive.org/web/20100613215026/http://www.thepathoflight.it/worken.php |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shamanic Music}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shamanic Music}} |

||

Latest revision as of 06:11, 25 August 2024

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Shamanic music is ritualistic music used in religious and spiritual ceremonies associated with the practice of shamanism. Shamanic music makes use of various means of producing music, with an emphasis on voice and rhythm. It can vary based on cultural, geographic, and religious influences.

Recently in Siberia, music groups drawing on knowledge of shamanic culture have emerged. In the West, shamanism has served as an imagined background to music meant to alter a listener's state of mind. Korea and Tibet are two cultures where the music of shamanic rituals has interacted closely with other traditions.

In shamanism, the shaman has a more active musical role than the medium in spirit possession.

Shamanic and musical performance

[edit]Since a Shamanic ritual includes a spiritual purpose and motive, it cannot be regarded as a musical performance, even though shamans use music (singing, drumming, and other instruments) in their rituals. Several things follow the ritual. First, a shamanic ritual performance is, above all, a series of actions and not a series of musical sounds.[1] Second, the shaman's attention is directed inwards towards her or his visualization of the spirit world and communication with the spirits, and not outwards to any listeners who might be present.[2] Third, it is important for the success of the ritual that it be given its own clearly defined context that is quite different from any kind of entertainment. Fourth, any theatrical elements that are added to impress an audience are of a type to make the contact with the spirits seem more real and not to suggest the performer's musical virtuosity. From a musical perspective, shamanic ritual performances have the distinctive feature of discontinuity. Breaks may happen because a spirit is proving difficult to communicate with, or the shaman needs to call a different spirit. Typically, phases of the performance are broken off abruptly, perhaps to be restarted after a gap, perhaps not.[3][4][5] The rhythmic dimension of the music of shamans' rituals has been connected to the idea of both incorporating the rhythms of nature and magically re-articulating them.[6]

Shamanism and possession

[edit]It has been argued[7] that shamanism and spirit possession involve contrasting kinds of special states of mind. The shaman actively enters the spirit world, negotiates with her or his helper spirit and then with other spirits as necessary, and moves between different territories of the spirit world. The possessed medium, on the other hand, is the passive recipient of a powerful spirit or god. This reflects the different uses of music involved. Possession music[8] is typically longer in duration, mesmeric, loud, and intense, with climaxes of rhythmic intensity and volume to which the medium has learned to respond by entering a trance state: the music is not played by the medium but by one or more musicians. In shamanism, the music is played by the shaman, confirms the shaman's power (in the words of the shaman's song), and is used actively by the shaman to modulate movements and changes of state as part of an active journey within the spirit world. In both cases, the connection between music and an altered state of mind depends on both psychoacoustic and cultural factors, and the music cannot be said to 'cause' trance-states.[9]

Use of sounds

[edit]Sound is tactile; whereas visual information is experienced at the surface, auditory information seems to be both outside and inside the body.[10] In oral cultures in which survival involves close contact with nature, sound often connects inner feelings to features of the natural environment. In many cases, this holds also for the music in shamanistic practice, including e.g. onomatopoeia, imitation of animal cries etc. The shaman's use of sound is to catalyze an imaginary inner environment which is experienced as a sacred space-time in which the shaman travels and encounters spirits. Sound, passing constantly between inner and outer, connects this imaginary space with the actual space of the ritual in which the shaman is moving and making ritual actions and gestures.

It has been suggested that the sound material used by the shaman constitutes a system of sounds.[11] This idea of semiotics of the sound material would imply a symbolic language shared between the shaman and the surrounding community. However, the evidence suggests that any symbolic language elements are understood only by the shaman and perhaps by other shamans initiated by this shaman. In other words, the symbolic language, if there is one, is more likely to be shared with the spirits than with a human community.[12]

A shaman may use different sounds for different ritual purposes:

- Setting up the sound-space of the ritual

- A very important element in Siberian shamanism is the use of hanging metallic objects – possibly including small bells – attached to the shaman's ritual cloak and to the inside of the drum and also sometimes to the beater. This sets up a continuously moving sound field, heard as a single complex sound.[13] A further element is the spatialization of sound brought about not only by the shaman's movement but also by techniques of singing into the drum to create the illusion of the voice coming from elsewhere. Different individual shamans and different local traditions may use different sounds. For example, in the south of Tuva and in Mongolia the khoums, or jaw harp is commonly used in shaman sing.[14]

- Preparation

- Particular sounds, like bells, may be used for purifying the place in which the ritual is to be performed.[15] This is because a ritual involving contact with the spirits is always potentially dangerous, and one of the dangers is that of pollution.

- Calling and sending back spirits

- A bell may also be used for calling or sending back spirits.[16] Shamans will also imitate the sounds of birds and animals in order to call spirits.[17] Sami shamanic singing, called Joik, is also about summoning, for example, animal spirits, rather than singing about them or representing them: the spirit is experienced as being present.[18]

- Healing

- Within shamanic ritual, sound can also be used as a healing power, conceived as a way of directing spiritual energy from the shaman into an afflicted person.[19] In Tuva sick persons are said to have been healed by the sound of a stringed instrument made from a tree struck by lightning.

Shaman's song

[edit]The shaman's song – or largish[20] in Tuvan – is personal to the shaman[21] and tells of her or his birthplace, initiation, ancestral pedigree, special gifts, and special connections to particular spirits. The melody and words are composed by the shaman and generally remain the same throughout the shaman's professional life. The largish is often sung near the beginning of the ritual and accompanied by drumming on the danger drum. It serves to remind the shaman of their shamanic identity and power. It proclaims the shaman's abilities and announces the shaman to the spirits. In some traditions, the shaman's song may be broken up into short sections, varied, and recombined in different performances.[22]

Korean shamanic music

[edit]Korea is the only country where shamanism appears to have been a state religion practiced by the literate classes, during the Three Kingdoms period (57 BC – 668 AD). Under successive dynasties, shamanism was gradually relegated to a popular or folk status with the arrival of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. The early official status of shamanism is the probable explanation for the fact that shamanic rituals in Korea developed highly complex and established forms. Correspondingly the music used in shamanic rituals is more elaborate in Korea than elsewhere. Furthermore, since the emergence of Korean contemporary nationalism, there has been a strong and sustained state intervention to preserve artistic traditions.[23] All of these factors make it uniquely difficult in Korea to distinguish the 'pure' from hybrid and concert forms of shamanic ritual music. For example, Sinawi is a musical form that can be used in shamanic rituals or accompany folk dances, or for urban concert performances. In the ritual context Sinai, is often performed by a small ensemble with the change hour-glass drum and two melodic instruments, often the Taegu flute and the piri oboe. In concert the ensemble is augmented with stringed instruments[24] Modern Sinai is played in a minor mode in 12/8 time.[25] The role of music in Korean shamanism seems intermediary between the possession trance model and the Siberian model: in the Kut ritual, the music, played by musicians, first calls on the god to possess the mudang (shaman), then accompanies the god during their time in the shaman's body, then sends back and placates the god at the end.[26] However, the shaman is the singer and dancer and the shaman directs the musicians.[27]

Bön shamanic music and Buddhist music

[edit]Before Buddhism came to Tibet, the local form of shamanism was Bön. Bön developed into an organised religion. When Buddhism arrived, both religions began competing with each other and incorporated many of each other's practices. The Bön shaman's drum on a pole became part of Tibetan Buddhist ritual music ensembles. Also, the shang – a kind of bell-cymbal – became incorporated into Buddhist rituals. It was formerly only used by shamans to clear away negative energy before shamanic rituals.[28][29][30] The practice of giving a sonorous identity to deities, of calling them and sending them back by means of sounds, may well have entered Tibetan Buddhist ritual from Bön tradition.[31]

Adoption by popular music

[edit]From the late 1980s with the loosening up of political restrictions several of Siberian native cultures underwent a cultural renaissance, shamans began to practice openly again, and musicians formed bands drawing on shamanic traditions. Cholbon[32] and AiTal,[33] in Sakha/Yakutsk, Biosyntes and early Yat-Kha in Tuva fall into this category. Nevertheless, the musicians involved, if sometimes unsure of their exact role, recognised an important difference between artists using shamanic themes and shamans themselves. In the West, bands began to apply the label 'shamanic' loosely to any music that might induce a trance state.[34][35] This was partly due to the rarity of actual recordings of shamans' rituals.[36] Meanwhile, the British-Tuvan group K-Space developed ways of combining improvisation, electronics, and experimental recording and montage techniques with the more shamanic side of Tuvan traditional music. In Hungary Vágtázó Halottkémek[37](in English: Galloping Coroners) later Vágtázó Csodaszarvas set out under the banner of shamanpunk to use ethnographic materials as manuals on how to reach and communicate ecstatic states. From 2005 Vágtázó Csodaszarvas (Galloping Wonder Stag) continued Vágtázó Halottkémek music philosophy turning it into a neotraditional music style closer to world music, replacing electronic guitars and drums with acoustic folk instruments.

Discography

[edit]

- Mongolie Chamanes et Lamas, Ocora C560059 (1994)

- Shamanic and Narrative Songs from the Siberian Arctic, Sibérie 1, Musique du Monde, BUDA 92564-2

- Musiche e sciamani, Musica del Mondo, Textus 001 (2000). Contains tracks assembled from the set of seven CDs of Siberian music on BUDA curated by Henri Lecomte. Sold with book (in Italian) Musiche e sciamani, ed Antonello Colimberti, Textus 2000.

- Kim Suk Chul / Kim Seok Chul Ensemble: Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard, JVC, VICG-5261 (1993)

- Trommeln der Schamanen, Tondokumente der Ausstellung, Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich (2007)

- Tuva, Among the Spirits, Smithsonian Folkways SFW 40452 (1999)

- Stepanida Borisova, Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (1) SOASIS 17 (2008)

- Chyskyyrai, Vocal Evocations of Sakha-Yakutia (2) SOASIS 18 (2008)

- Gendos Chamzyrzn, Kamlaniye, Long Arms (Russia) CDLA 04070 (2004)

- Tabuk, Contemporary Sakha Folk Music, Feelee LP (Russia) FL 3018/019 (1991)

References

[edit]- Fremont E.Besmer, Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983

- Otgonbayar Chuluunbaatar, Musical Instruments as Paraphernalia of the Shamans in Northern Mongolia, in Studia Instrumentorum Musicae Popularis (New Series), ed Gisa Jähnichen, MV-Wissenschaft Verlag, 2017, p 1-32.

- Antonello Colimberti (ed) (in Italian) Musiche e sciamani, Textus, Milan 2000

- Shamanism, The Spirit World of Korea, eds Chai-shin Yu and R.Guisso, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley California 1988

- Vilmos Diószegi, Tracing Shamans in Siberia Anthropological Publications, Netherlands 1968.

- Roberte Hamayon, (in French) Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme, in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995.

- Roberte Hamayon, (in French) Gestes et Sons, Chamane et Barde, in Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19, Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006

- Mireille Helffer (in French) Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain in L'Homme 171-2, Paris 2004

- Tim Hodgkinson, Musicians, Carvers, Shamans, Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006)

- Tim Hodgkinson, Siberian shamanism and improvised music, Contemporary Music Review vol 14, parts 1–2, Netherlands, Harwood,1996.

- Mihály Hoppál, Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies, in Mongush Kenin Lopsan Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva, Istor Budapest 1997

- Mihály Hoppál, Studies on Eurasian Shamanism in Shamans and Cultures in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258–288 Istor Budapest 1993

- Keith Howard, Sonic Transformations of Shamanic Representations in AHRP Research Centre Newsletter 4, SOAS 2004.

- Keith Howard, Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity v. 1 (SOAS Musicology Series) 2006

- Caroline Humphrey, Shamans and elders. Oxford, OUP1996.

- Ronald Hutton, The Shamans of Siberia, Isle of Avalon Press, 1993

- Margaret J. Kartomi, On concepts and classifications of musical instrumentsUniversity of Chicago Press, 1990 ISBN 978-0-226-42549-8

- Henri Lecomte, (in French) Approches Autochtones du Chamanisme Sibérien au début du XXI Siècle, in Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19, Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006

- Theodore Levin, Where Rivers and Mountains Sing, Indiana University Press 2006.

- Mongush Kenin Lopsan, Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva Istor Budapest 1997

- Terence McKenna, The Archaic revival Harper Collins 1991

- Rodney Needham, Percussion and Transition, Man 2:606-14. 1967

- Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word, Methuen, 1982

- Carole Pegg, Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative, University of Washington Press, 2001.

- Tina Ramnarine, Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik, Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009

- Gilbert Rouget, Music and Trance, University of Chicago Press 1985

- Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) La musica sciamanica, Xenia 2004

- Maria Kongin Seo, Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul, Routledge 2002

- Andrew Stiller, Handbook of Instrumentation, University of California Press, 1985, ISBN 0-520-04423-1

- Anna Szemere Up From the Underground – The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary Penn State Press 2001

- Michael Taussig, The Nervous System, Routledge 1992

- Sevyan Vainshtein, The Tuvan Shaman's Drum and the ceremony of its Enlivening, in V.Dioszegi (ed), Popular Beliefs and Folklore in Siberia, Bloomington 1968

- Aimar Ventsel, Sakha Pop Music http://www.princeton.edu/~restudy/soyuz_papers/Ventsel.pdf[permanent dead link]

- Marilyn Walker, Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia, in Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p40-48

- Damian Walter, The Medium of the Message: Shamanism as Localised Practice in the Nepal Himalayas in The Archaeology of Shamanism, ed Neil Price, Routledge 2001

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mihály Hoppál, Tracing Shamanism in Tuva: A History of Studies, in Mongush Kenin Lopsan, Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva, Istor Budapest 1997 p 129 "...the struggle with the harmful spirits during which great drumbeats indicated that the shaman had driven a "steel arrow" for each beat into the spirits of sickness."

- ^ Tim Hodgkinson, Musicians, Carvers, Shamans, Cambridge Anthropology vol 25, no 3, (2005/2006) p 9."Sergei Tumat (a Tuvan shaman who had previously studied music): "When I shamanize, I'm not here, not in the place where I'm playing the dungur drum, it's just my material body that's there: I'm away with the spirits, that's where my total attention is. If someone touches me, tries to get my attention there in the yurt, that's dangerous, it would be like falling a long way: so it's completely different from playing music to an audience, where you have to be there, to be attentive to what your material body is doing, to everything I learned in music school...""

- ^ Carole Pegg, Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative, University of Washington Press, 2001, p135-6

- ^ Ronald Hutton, The Shamans of Siberia, Isle of Avalon Press, 1993, p29 and p31

- ^ Caroline Humphrey, Shamans and elders. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235-7

- ^ Carlo Serra, (in Italian)Ritmo e ciclità nella cultura sciamanica, in Antonello Colimberti (ed) Musiche e sciamani, Textus, Milan 2000, p67

- ^ Gilbert Rouget, Music and Trance, University of Chicago Press 1985 p125

- ^ Fremont E.Besmer, Horses, Musicians and Gods: The Hausa Cult of Possession-Trance. Ahmadu Bello UP 1983

- ^ Roberte Hamayon,(in French) Pour en finir avec la 'trance' et 'l'extase' dans l'étude du chamanisme, in Etudes mongoles et sibériennes 26: Variations Chamaniques 2, 1995, p155 seq.

- ^ Walter Ong, Orality and Literacy: The technologizing of the word, Methuen, 1982

- ^ Massimo Ruggero, (in Italian) La musica sciamanica . – Xenia – 2004, p. 2

- ^ Michael Taussig, The Nervous System . – Routledge – 1992 p.177

- ^ Andrew Stiller, Handbook of Instrumentation, University of California Press, 1985, p 121, ISBN 0-520-04423-1

- ^ Carole Pegg, Mongolian Music, Dance and Oral Narrative, University of Washington Press, 2001, p124

- ^ Marilyn Walker, Music as Knowledge in Shamanism and Other Healing Traditions of Siberia, in Arctic Anthropology.2003; 40(2): p45

- ^ Maria Kongin Seo, Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul, Routledge 2002 p14

- ^ Theodore Levin, Where Rivers and Mountains Sing, (Indiana University Press 2006)

- ^ Tina Ramnarine, Acoustemology, Indigeneity & Joik, Ethnomusicology vol 53, no 2, spring/summer 2009, p. 191

- ^ Marilyn Walker, 2003, p46

- ^ Mongush Kenin Lopsan, Shamanic Songs and Myths of Tuva Istor Budapest 1997

- ^ Mihály Hoppál, Studies on Eurasian Shamanism in Shamans and Cultures in Mihály Hoppál and Keith Howard eds pp258-288 Istor Budapest 1993

- ^ Caroline Humphrey, Shamans and elders. Oxford, OUP1996, p 235

- ^ Keith Howard, Perspectives on Korean Music: Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity v. 1 (SOAS Musicology Series) 2006

- ^ Kyo-Chul Chung CD notes for Seoul Ensemble of Traditional Music World Network 12, WDR 54.039.

- ^ CD notes forA selection of Korean traditional music, volume 2. Instrumental Music 2, SBCD-4380-2

- ^ Shamanism, The Spirit World of Korea, eds Chai-shin Yu and R.Guisso, Asian Humanities Press, Berkeley California 1988

- ^ Lee Bo Hyeong CD notes for Kim Suk Chul Ensemble: Shamanistic Ceremonies of the Eastern Seaboard, JVC, VICG-5261 (1993)

- ^ Margaret J. Kartomi On concepts and classifications of musical instrumentsUniversity of Chicago Press, 1990 pp 75–83 ISBN 978-0-226-42549-8

- ^ "The Singing Bowls of Tibet". Archived from the original on 2009-02-16. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ "The Path of Light". Archived from the original on 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Mireille Helffer (in French)Traditions musicales dans un monastère du Bouddhisme Tibétain in L'Homme 171-2, Paris 2004 pp 183–184

- ^ Henri Lecomte,(in French) Approches Autochtones du Chamanisme Sibérien au début du XXI Siècle, in Chamanisme et Possession, Cahiers de Musiques Traditionelles 19, Ateliers d'Ethnomusicologie, Genève, 2006

- ^ Aimar Ventsel, Sakha Pop Music p.10 http://www.princeton.edu/~restudy/soyuz_papers/Ventsel.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Keith Howard, Sonic Transformations of Shamanic Representations in AHRP Research Centre Newsletter 4, SOAS 2004, p19

- ^ Terence McKenna, The Archaic revival Harper Collins 1991

- ^ Gilbert Rouget, Music and Trance, University of Chicago Press 1985 p130

- ^ Kathryn Milun quotes Anna Szemere: Up From the Underground – The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary Penn State Press 2001, http://www.pum.umontreal.ca/revues/surfaces/vol1/milun.html Archived 2009-05-05 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- https://web.archive.org/web/20130724093513/http://vhk.mediastorm.hu/

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110622115511/http://www.soas.ac.uk/musicanddance/projects/project6/essays/file45912.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20090216183730/http://frankperry.co.uk/Tibetan%20Bowls.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100613215026/http://www.thepathoflight.it/worken.php