String Quartets, Op. 33 (Haydn): Difference between revisions

m Fixed consecutive punctuation error and general fixes (task 3) |

→top: "suspect"? what, are the quartets felons? |

||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Six string quartets by Joseph Haydn}} |

|||

{{Redirect|The Jokes|the 2004 comedy film|The Jokes (film)}} |

{{Redirect|The Jokes|the 2004 comedy film|The Jokes (film)}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} |

||

The '''Op. 33 String Quartets''' were written by [[Joseph Haydn]] in the summer and Autumn of 1781 for the Viennese publisher [[Artaria]]. This set of [[string quartet]]s has several nicknames, the most common of which is the "Russian" quartets, because Haydn dedicated the quartets to the [[Paul I of Russia|Grand Duke Paul of Russia]] and many (if not all) of the quartets were premiered on Christmas Day, 1781, at the Viennese apartment of the Duke's wife, the [[Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)|Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna]].<ref name="berger">Berger, Melvin. Guide to Chamber Music. New York: Dover, 1985. 196–201.</ref> |

The '''Op. 33 String Quartets''' were written by [[Joseph Haydn]] in the summer and Autumn of 1781 for the Viennese publisher [[Artaria]]. This set of [[string quartet]]s has several nicknames, the most common of which is the "Russian" quartets, because Haydn dedicated the quartets to the [[Paul I of Russia|Grand Duke Paul of Russia]] and many (if not all) of the quartets were premiered on Christmas Day, 1781, at the Viennese apartment of the Duke's wife, the [[Maria Feodorovna (Sophie Dorothea of Württemberg)|Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna]].<ref name="berger">Berger, Melvin. Guide to Chamber Music. New York: Dover, 1985. 196–201.</ref> Some scholars theorize that the "Russian" quartets were the inspiration for [[Haydn Quartets (Mozart)|Mozart's six string quartets dedicated to Haydn]],<ref>Adolfo Betti, "Quartet: its origins and development", in Cobbett (1929)</ref> but no direct evidence has been found. |

||

==Opus 33 No. 1== |

==Opus 33 No. 1== |

||

| Line 58: | Line 59: | ||

The "Rondo" results in an ABACA form. Chronologically, the first [[refrain]] (A) (mm. 1–35) beginning in E{{music|flat}} major, repeats each section, (a) and (ba), forming ({{not a typo|aababa}}). In the first episode (B) (mm. 36–71) beginning in A{{music|flat}} major, moves to F minor and finally resolves to E{{music|flat}} major at the beginning of the second refrain (A) (mm. 72–106), which is almost an exact repetition of the first refrain (aba) with the only change being the omission of the repeats. The second refrain is not only the arrival point of the [[Tonic (music)|tonic]], but is also the final point of [[modulation]] for the remainder of the piece. The piece then progresses to new thematic material in the second episode (C) (mm. 107–140), but, again, does not modulate to a new key. After the new material, the final refrain (A) (mm. 141–147), should be considered A' due to the refrain material being condensed. |

The "Rondo" results in an ABACA form. Chronologically, the first [[refrain]] (A) (mm. 1–35) beginning in E{{music|flat}} major, repeats each section, (a) and (ba), forming ({{not a typo|aababa}}). In the first episode (B) (mm. 36–71) beginning in A{{music|flat}} major, moves to F minor and finally resolves to E{{music|flat}} major at the beginning of the second refrain (A) (mm. 72–106), which is almost an exact repetition of the first refrain (aba) with the only change being the omission of the repeats. The second refrain is not only the arrival point of the [[Tonic (music)|tonic]], but is also the final point of [[modulation]] for the remainder of the piece. The piece then progresses to new thematic material in the second episode (C) (mm. 107–140), but, again, does not modulate to a new key. After the new material, the final refrain (A) (mm. 141–147), should be considered A' due to the refrain material being condensed. |

||

The 'joke' referred to in the nickname is to be found at the conclusion of this movement. It begins with a [[Glossary of musical terminology#G|grand pause]] that makes the audience wonder if the piece is over. This is followed by a sudden forte sixteenth note in the beginning of the [[Tempo#Basic tempo markings|adagio]] that shocks the audience. After this, the first violin plays the A [[Theme (music)|theme]] of the opening phrase with rests interrupting the music every two bars. The rests get progressively longer, giving the impression that the piece is over many times in a row, after which the music ends abruptly with a repeat of the movement's opening phrase, |

The 'joke' referred to in the nickname is to be found at the conclusion of this movement. It begins with a [[Glossary of musical terminology#G|grand pause]] that makes the audience wonder if the piece is over. This is followed by a sudden forte sixteenth note in the beginning of the [[Tempo#Basic tempo markings|adagio]] that shocks the audience. After this, the first violin plays the A [[Theme (music)|theme]] of the opening phrase with rests interrupting the music every two bars. The rests get progressively longer, giving the impression that the piece is over many times in a row, after which the music ends abruptly with a repeat of half of the movement's opening phrase, leaving the work hanging in mid-air. |

||

==Opus 33 No. 3== |

==Opus 33 No. 3== |

||

Latest revision as of 05:35, 10 July 2024

The Op. 33 String Quartets were written by Joseph Haydn in the summer and Autumn of 1781 for the Viennese publisher Artaria. This set of string quartets has several nicknames, the most common of which is the "Russian" quartets, because Haydn dedicated the quartets to the Grand Duke Paul of Russia and many (if not all) of the quartets were premiered on Christmas Day, 1781, at the Viennese apartment of the Duke's wife, the Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna.[1] Some scholars theorize that the "Russian" quartets were the inspiration for Mozart's six string quartets dedicated to Haydn,[2] but no direct evidence has been found.

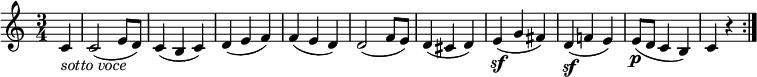

Opus 33 No. 1

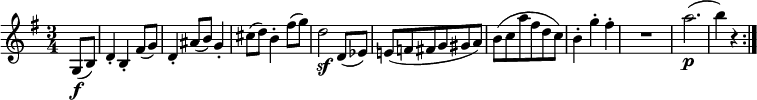

[edit]This quartet in B minor is numbered variously as No. 31, Hob. III:37, and FHE No. 70.

The first movement pretends to start in D major before settling in the home key of B minor,[3] echoed by Haydn's later quartet in B minor, Op. 64, No. 2.

Opus 33 No. 2

[edit]This quartet in E♭ major, nicknamed "The Joke" is numbered in variously as No. 30, Hob. III:38 and FHE No. 71.

Fourth movement

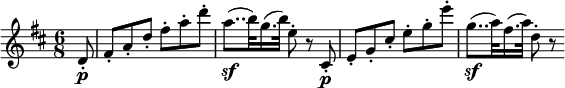

[edit]The fourth movement implemented a lighter character, originating from Haydn's first shift from the minuet to the scherzo. It also portrayed some new features in Haydn's compositions, for example, the Rondo form, which satisfied audiences since the form was becoming enormously popular at this time. In a letter to Artaria, Haydn boasted about his pieces by saying, they are "a new and entirely special kind". The rondo form of the final movement remains true to its definition by always returning to the tonic in the refrain.[4]

Form

[edit]The "Rondo" results in an ABACA form. Chronologically, the first refrain (A) (mm. 1–35) beginning in E♭ major, repeats each section, (a) and (ba), forming (aababa). In the first episode (B) (mm. 36–71) beginning in A♭ major, moves to F minor and finally resolves to E♭ major at the beginning of the second refrain (A) (mm. 72–106), which is almost an exact repetition of the first refrain (aba) with the only change being the omission of the repeats. The second refrain is not only the arrival point of the tonic, but is also the final point of modulation for the remainder of the piece. The piece then progresses to new thematic material in the second episode (C) (mm. 107–140), but, again, does not modulate to a new key. After the new material, the final refrain (A) (mm. 141–147), should be considered A' due to the refrain material being condensed.

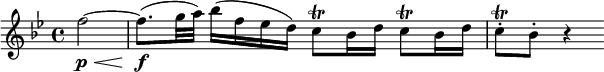

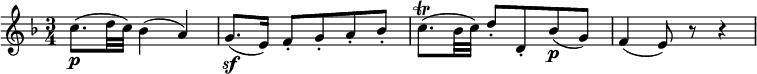

The 'joke' referred to in the nickname is to be found at the conclusion of this movement. It begins with a grand pause that makes the audience wonder if the piece is over. This is followed by a sudden forte sixteenth note in the beginning of the adagio that shocks the audience. After this, the first violin plays the A theme of the opening phrase with rests interrupting the music every two bars. The rests get progressively longer, giving the impression that the piece is over many times in a row, after which the music ends abruptly with a repeat of half of the movement's opening phrase, leaving the work hanging in mid-air.

Opus 33 No. 3

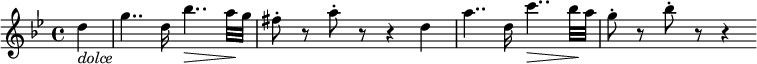

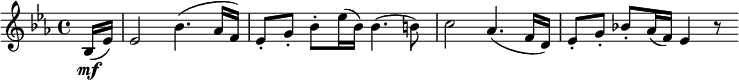

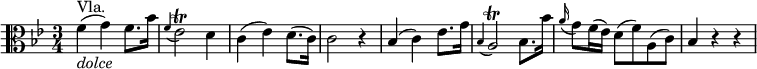

[edit]This quartet in C major, nicknamed "The Bird" is numbered variously as No. 32, Hob. III:39, and FHE No. 72.

The first movement opens with a melody in the first violin featuring repeated notes. Grace notes are inserted between the repeated notes which gives the melody a "birdlike quality"[1] and hence gives the quartet its nickname.

Opus 33 No. 4

[edit]This quartet in B♭ major is numbered in variously as No. 34, Hob. III:40 and FHE No. 73.

- Allegro moderato, 4

4

- Scherzo: Allegretto, 3

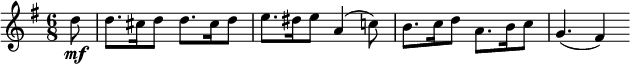

4![{ \relative d'' { \key bes \major \time 3/4

d4~ \mf d8.[ f16 es8. g16)] | f4( d bes) | c4~ c8.[ es16 d8. f16)] | es4( c a) |

bes2.~ | bes2 b4( | c4 ) es8.[ c16 a8. c16] | bes4 r r \bar ":|." }}](/upwiki/score/5/9/59mtmgph7gkzvt502fuj6vaabchqfzj/59mtmgph.png)

- Largo, 3

4 in E♭ major

- Finale: Presto, 2

4![{ \relative d' { \key bes \major \time 2/4

\partial 8 d16( \mf f) | bes8-. bes-. bes-. es16( d) | c8-. c-. c-. f16( es) | d8-.[ bes'( g es)] |

d4( c8) es16( c) | a8-. c'-. c-. a,16( c) | es8-. es,-. es-. d16( f) | bes8-. d-. d16( c bes a) | bes4 r8 \bar ":|." }}

\layout { \context {\Score \override SpacingSpanner.common-shortest-duration = #(ly:make-moment 1/8) }}](/upwiki/score/k/b/kb7qgcaplkc101jr1wz5arc5hjmesta/kb7qgcap.png)

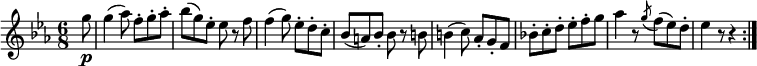

Opus 33 No. 5

[edit]This quartet in G major, nicknamed "How Do You Do", is numbered in variously as No. 29, Hob. III:41, and FHE No. 74.

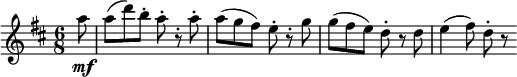

- Vivace assai, 2

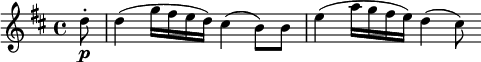

4![{ \relative d' { \key g \major \time 2/4

d4.( \pp e16 fis) | g4-. r8 \bar ".|:" b8 _\markup { \italic "poco" \musicglyph #"f" } |

\afterGrace b4.( { d32 c b } c8) | d8-.[ d-. d-. a-.] | \afterGrace a4.( { c32 b a } b8) |

c8-.[ c-. c-. g-.] | g2 | a4.( b16 c) | d,4.( e16 fis) | g4 \ff r8 }}](/upwiki/score/n/6/n6rc7kp5cdtn0cf5g7gq1rigrw74dwh/n6rc7kp5.png)

- Largo e cantabile, 4

4 in G minor

- Scherzo: Allegro, 3

4

- Finale: Allegretto, 6

8

The first theme of the opening movement begins and ends with the same rising four-note cadence that gives the quartet its nickname. When the cadence appears at the end of the movement, it is repeated so as to emphasize the end of the movement and not the beginning of the theme.

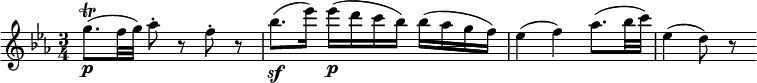

The second movement is an aria in G minor for first violin over a steady accompaniment in the other three instruments. The melody bears a strong resemblance to the oboe theme that begins the arioso "Che puro ciel" from Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice, which Haydn had directed at Eszterháza in 1778.[5] The movement contains what is essentially a written-out, accompanied cadenza from mm. 41–50, and soon afterwards ends with a unison pizzicato G.

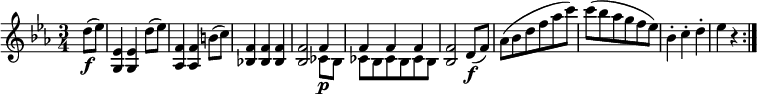

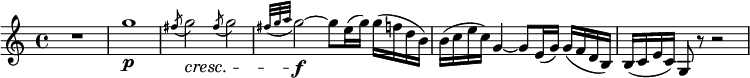

Opus 33 No. 6

[edit]This quartet in D major is numbered in variously as No. 33, Hob. III:42 and FHE No. 75.

- Vivace assai, 6

8

- Andante, 4

4 in D minor

- Scherzo: Allegretto, 3

4

- Finale: Allegretto, 2

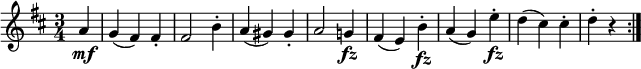

4![{ \relative d'' { \key d \major \time 2/4

\partial 8 d8-. \mf | d,8.( fis32 a) g8-. e-. | fis8-.[ g-. e-. a-.] | fis8-.[ b-. a-. gis-.] | gis4( a8) e'-. |

a,,8~( a32 cis e g!) fis8-. b-. \p | e,8.( fis32 g) a8-. d-. \f | b8-.[ e-. d-. cis-.] | cis4( d8) \bar ":|." }}](/upwiki/score/s/q/sqznn17pj2qhm6e6kfql5e5rcq483uf/sqznn17p.png)

The finale is in double variation form (A B A1 B1 A2) with themes in D major and D minor.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Berger, Melvin. Guide to Chamber Music. New York: Dover, 1985. 196–201.

- ^ Adolfo Betti, "Quartet: its origins and development", in Cobbett (1929)

- ^ Rosen, Charles (1997). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, New York: W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-00653-0.

- ^ Burkholder, J. Peter. (2006). Norton Anthology of Western Music. New York. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- ^ Heartz, Daniel, Mozart, Haydn and Early Beethoven 1781–1802, p. 315, Norton (2009), ISBN 978-0-393-06634-0

Bibliography

[edit]- Bernhard A. Macek (2012) Haydn, Mozart und die Großfürstin: Eine Studie zur Uraufführung der "Russischen Quartette" op. 33 in den Kaiserappartements der Wiener Hofburg. (Wien: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.) ISBN 3-901568-72-7.

- Richard Taruskin (2010). Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. The Oxford History of Western Music 2. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 542–555. ISBN 978-0-19-538482-6. (detailed analysis of the "Joke" Quartet).

}

\new Voice { \voiceTwo s fis8^1 | s8 fis[ s fis s fis]} >> \oneVoice | fis2( \p g4) \< |

g4-. g-. g-. | <b b,>2( \sf \> g4) \! | e4( cis) a-. | d4-. r \bar ":|." }}

\layout { \context {\Score \override SpacingSpanner.common-shortest-duration = #(ly:make-moment 1/4) }}](/upwiki/score/o/9/o9fqxoo57pww76lffjh3y4ajnlaf74f/o9fqxoo5.png)

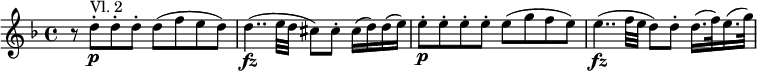

![{ \relative b { \key b \minor \time 2/4

\partial 4 b8-. \mf b-.| b8([ \trill d) fis-. fis-.] | fis4 b,8-. b-. | b8([ \trill e) g-. g-.] |

g4 ais,8-. ais-. | ais8([ cis) fis-. e-.] | \acciaccatura e8 \afterGrace d4( \trill { cis16 d) } cis4 |

b4. d8-. | d4( cis8) e-. | e4( dis8) fis-. | e8.( \trill fis16) g8-. g-. | fis8-. b,-. d16( cis b ais) | b4 }}

\layout { \context {\Score \override SpacingSpanner.common-shortest-duration = #(ly:make-moment 1/4) }}](/upwiki/score/0/e/0ezbvfqe646r62zr909z11dgffkf9qj/0ezbvfqe.png)

![{ \relative g'' { \key c \major \time 2/4

g8-.[ \p e-. g-. e-.] | g16-. f-. e-. f-. g8-. e-. | g16-. f-. e-. f-. g-. f-. e-. f-. | g16-. f-. e-. f-. g8-. e-. |

a8 \f a a16( g f g) | f8 f a16( g f g) | e8 e g16( f e d) | c4( b8) r \bar ":|." }}

\layout { \context {\Score \override SpacingSpanner.common-shortest-duration = #(ly:make-moment 1/8) }}](/upwiki/score/f/4/f4zfxy0rhxedx81t4acep2zxuqvjwxy/f4zfxy0r.png)