Daniel Sickles's leg: Difference between revisions

BrokenSegue (talk | contribs) →Leg wound and later display: add image |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Amputated appendage of a Union Army general}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

{{good article}} |

||

[[File:Sickles leg.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Broken leg bone and cannonball |Sickles's leg bones on display]] |

[[File:Sickles leg.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Broken leg bone and cannonball |Sickles's leg bones on display]] |

||

The [[amputated]] right leg of [[Union Army]] general [[Daniel Sickles]], lost after a cannonball wound suffered at the [[Battle of Gettysburg]] on July 2, 1863, is displayed at the [[National Museum of Health and Medicine]]. |

The [[amputated]] right lower leg of [[Union Army]] general [[Daniel Sickles]], lost after a cannonball wound suffered at the [[Battle of Gettysburg]] on July 2, 1863, is displayed at the [[National Museum of Health and Medicine]]. |

||

Sickles was a former [[New York (state)|New York]] politician who entered the army after the outbreak of the [[American Civil War]] in 1861. After originally commanding the [[Excelsior Brigade]], Sickles was promoted to [[Major general (United States)|major general]] in 1862 and later commanded the [[III Corps (Union Army)|III Corps]] at the battles of [[Battle of Chancellorsville|Chancellorsville]] and Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, Sickles moved the III Corps forward from his assigned position, and it was shattered by a [[Confederate States Army|Confederate]] attack. During the fighting, he was struck in the leg by a [[solid shot]]; the wound later required amputation above the knee. After the amputation, the limb was donated to the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine), where it was used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma. Sickles sometimes visited the limb afterwards, and it remains a popular attraction at the museum. |

Sickles was a former [[New York (state)|New York]] politician who entered the army after the outbreak of the [[American Civil War]] in 1861. After originally commanding the [[Excelsior Brigade]], Sickles was promoted to [[Major general (United States)|major general]] in 1862 and later commanded the [[III Corps (Union Army)|III Corps]] at the battles of [[Battle of Chancellorsville|Chancellorsville]] and Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, Sickles moved the III Corps forward from his assigned position, and it was shattered by a [[Confederate States Army|Confederate]] attack. During the fighting, he was struck in the leg by a [[solid shot]]; the wound later required amputation above the knee. After the amputation, the limb was donated to the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine), where it was used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma. Sickles sometimes visited the limb afterwards, and it remains a popular attraction at the museum. |

||

| Line 11: | Line 12: | ||

==Leg wound and later display== |

==Leg wound and later display== |

||

[[File:The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology - Figure 11.jpg|thumb|alt=Sickles above his shattered leg|Sickles and his shattered leg]] |

|||

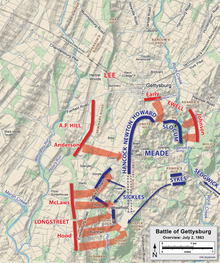

Early on July 2, 1863, with the Battle of Gettysburg ongoing, Sickles became concerned about the suitability of the position the III Corps was assigned to defend.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=90{{endash}}91}} He later decided to abandon the position he had been assigned and moved his troops forward to another line along the [[Emmitsburg Road]].{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=102{{endash}}103}} While this new position had some positive features, it was also exposed and the prior position had been adequate.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=95{{endash}}97}} Confederate troops commanded by [[James Longstreet]] attacked Sickles's new position, and the III Corps was overrun.{{sfn|Warner|2006|p=447}} With his line crumbling, Sickles rode up to the portion of III Corps at [[the Peach Orchard]], which was falling apart. After watching the retreat of the [[141st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment]], he headed towards the Trostle Farm.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|p=333}} |

Early on July 2, 1863, with the Battle of Gettysburg ongoing, Sickles became concerned about the suitability of the position the III Corps was assigned to defend.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=90{{endash}}91}} He later decided to abandon the position he had been assigned and moved his troops forward to another line along the [[Emmitsburg Road]].{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=102{{endash}}103}} While this new position had some positive features, it was also exposed and the prior position had been adequate.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=95{{endash}}97}} Confederate troops commanded by [[James Longstreet]] attacked Sickles's new position, and the III Corps was overrun.{{sfn|Warner|2006|p=447}} With his line crumbling, Sickles rode up to the portion of III Corps at [[the Peach Orchard]], which was falling apart. After watching the retreat of the [[141st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment]], he headed towards the Trostle Farm.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|p=333}} |

||

After riding onto a [[hillock|knoll]] for a better view of the fighting, Sickles was hit in the right leg by a {{convert|12|lb|kg|adj=on}} [[solid shot]].<ref name="pearlstein">{{cite web |last1=Pearlstein |first1=Kristen |title=Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles: His Contribution to the Army Medical Museum |url=https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/micrograph/index.cfm/posts/2021/maj_gen_daniel_e_sickles |publisher=National Museum of Health and Medicine |access-date=15 February 2022 |date=July 1, 2021}}</ref> The shot did not startle Sickles's horse, and he dismounted and a [[tourniquet]] was applied to the wound. After transferring command of the III Corps to [[David B. Birney]], Sickles was taken off the field on a stretcher while puffing on a cigar.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=333{{endash}}334}} The injury had broken both of the bones of his lower right leg.<ref name="demetrick">{{cite web |last1=DeMetrick |first1=Alex |title=Civil War General's Leg on Display In Maryland |url=https://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2011/05/17/civil-war-generals-leg-on-display-in-maryland/ | |

After riding onto a [[hillock|knoll]] for a better view of the fighting, Sickles was hit in the right leg by a {{convert|12|lb|kg|adj=on}} [[solid shot]].<ref name="pearlstein">{{cite web |last1=Pearlstein |first1=Kristen |title=Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles: His Contribution to the Army Medical Museum |url=https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/micrograph/index.cfm/posts/2021/maj_gen_daniel_e_sickles |publisher=[[National Museum of Health and Medicine]] |access-date=15 February 2022 |date=July 1, 2021 |archive-date=15 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220215032545/https://www.medicalmuseum.mil/micrograph/index.cfm/posts/2021/maj_gen_daniel_e_sickles |url-status=dead }}</ref> The shot did not startle Sickles's horse, and he dismounted and a [[tourniquet]] was applied to the wound. After transferring command of the III Corps to [[David B. Birney]], Sickles was taken off the field on a stretcher while puffing on a cigar.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|pp=333{{endash}}334}} The injury had broken both of the bones (the [[tibia]] and the [[fibula]]) of his lower right leg.<ref name="demetrick">{{cite web |last1=DeMetrick |first1=Alex |title=Civil War General's Leg on Display In Maryland |url=https://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2011/05/17/civil-war-generals-leg-on-display-in-maryland/ |website=[[WJZ-TV]] |access-date=15 February 2022 |date=May 7, 2011 |archive-date=15 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220215040438/https://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2011/05/17/civil-war-generals-leg-on-display-in-maryland/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The medical director of the III Corps, Thomas Sim, performed an [[amputation]] of Sickles's leg. It was initially thought that the cut could be made below the knee, but upon further inspection it was determined that the damage was more severe than first thought, and an amputation above the knee was required.<ref name="pearlstein" /> The general had been anesthetized with [[chloroform]] before the amputation.<ref name="wapo">{{cite news |last1=Wheeler |first1=Linda |title=Union General Remained Attached to Museum Display of Amputated Limb |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2001/07/12/union-general-remained-attached-to-museum-display-of-amputated-limb/bf1b7781-a2cc-468f-81dc-4e2bff7ac12c/ |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |access-date=15 February 2022 |date=July 12, 2001 |archive-date=27 August 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170827075428/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2001/07/12/union-general-remained-attached-to-museum-display-of-amputated-limb/bf1b7781-a2cc-468f-81dc-4e2bff7ac12c/ |url-status=live }}</ref> After the limb was cut off, it was kept, possibly by Sim.{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|p=334}} |

||

[[File:Viewing Major General Daniel E. Sickles leg (MIS 63-120-5), National Museum of Health and Medicine (4948091919).jpg|thumb|Viewing the leg at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (1963)]] |

|||

[[File:Gens. Sickles, Carr & Graham. Taken near Trostle's barn, Gettysburg Battlefield - on spot where General Sickles lost his leg, July 2nd, 1863 LCCN2004673094.jpg|thumb|alt=Sickles re-visiting the battlefield where he lost his leg|Sickles re-visiting the battlefield where he lost his leg]] |

|||

| ⚫ | Aware that the [[National Museum of Health and Medicine|Army Medical Museum]] (since renamed the National Museum of Health and Medicine) had been recently founded, Sickles had the leg forwarded to the museum in a coffin-shaped box, as it had begun accumulating "specimens of morbid anatomy".{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} The damaged [[tibia]] and [[fibula]] were stabilized with wire and used as a museum specimen.<ref name="pearlstein" /> The bones were used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma.<ref name="demetrick" /> Sickles recovered quickly from the wound,{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} but never held a field command again.{{sfn|Warner|2006|p=447}} He sometimes visited the limb on the anniversary of its loss,{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} and sometimes brought visitors with him, including, on one occasion, [[Mark Twain]] who stated that he believed the general valued the lost leg more than his still-extant one.<ref name="pearlstein" /> Upon his first visit to the limb, Sickles allegedly berated the museum for not preserving his foot as well.{{sfn|Hessler|2009|p=315}} He retired from the army in 1869, was a diplomat to Spain, served another term in Congress, and died |

||

| ⚫ | Aware that the [[National Museum of Health and Medicine|Army Medical Museum]] (since renamed the National Museum of Health and Medicine) had been recently founded, Sickles had the leg forwarded to the museum in a coffin-shaped box, as it had begun accumulating "specimens of morbid anatomy".{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} The damaged [[tibia]] and [[fibula]] were stabilized with wire and used as a museum specimen.<ref name="pearlstein" /> The bones were used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma.<ref name="demetrick" /> Sickles recovered quickly from the wound,{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} but never held a field command again.{{sfn|Warner|2006|p=447}} He sometimes visited the limb on the anniversary of its loss,{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} and sometimes brought visitors with him, including, on one occasion, [[Mark Twain]] who stated that he believed the general valued the lost leg more than his still-extant one.<ref name="pearlstein" /> Upon his first visit to the limb, Sickles allegedly berated the museum for not preserving his foot as well.{{sfn|Hessler|2009|p=315}} He retired from the army in 1869, was a diplomat to Spain, served another term in Congress, and died on May 3, 1914, at age 94.{{sfn|Warner|2006|p=447}} |

||

The leg bones have since been enclosed in a glass case{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|p=534 fn. 134}} and have been reported as of 2014 to be one of the museum's most requested exhibits.{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} For a time in 2011, the bones were displayed at [[Fort Detrick]],<ref name="demetrick" /> but as of 2021 are again displayed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.<ref name="pearlstein" /> The bones are attached to a wooden stand by metal prongs and are displayed next to a cannonball of the type that caused the wound.<ref name="wapo" /> |

The leg bones have since been enclosed in a glass case{{sfn|Pfanz|1987|p=534 fn. 134}} and have been reported as of 2014 to be one of the museum's most requested exhibits.{{sfn|Clarke|2014|p=1051}} For a time in 2011, the bones were displayed at [[Fort Detrick]],<ref name="demetrick" /> but as of 2021 are again displayed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.<ref name="pearlstein" /> The bones are attached to a wooden stand by metal prongs and are displayed next to a cannonball of the type that caused the wound.<ref name="wapo" /> |

||

==See also== |

|||

{{Commons}} |

|||

* [[Stonewall Jackson's arm]] |

|||

* [[Lord Uxbridge's leg]] |

|||

* [[Attempted theft of George Washington's skull]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 34: | ||

==Sources== |

==Sources== |

||

* {{cite journal |last=Clarke |first=Tim |

* {{cite journal |last=Clarke |first=Tim Jr. |title=Sickles' Leg and the Army Medical Museum |date=2014 |journal=[[Military Medicine (journal)|Military Medicine]] |volume=179 |issue=8 |page=1051 |pmid=25181725 |doi=10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00182|doi-access=free }} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Hessler |first=James A. |title=Sickles at Gettysburg |date=2009 |publisher=Savas Beatie |location=New York |isbn=978-1-932714-84-5}} |

* {{cite book |last=Hessler |first=James A. |title=Sickles at Gettysburg |date=2009 |publisher=Savas Beatie |location=New York |isbn=978-1-932714-84-5}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Pfanz |first=Harry W. |title=Gettysburg: The Second Day |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |date=1987 |location=Chapel Hill, North Carolina |isbn=978-0-8078-4730-5}} |

* {{cite book |last=Pfanz |first=Harry W. |title=Gettysburg: The Second Day |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |date=1987 |location=Chapel Hill, North Carolina |isbn=978-0-8078-4730-5}} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Warner |first=Ezra J. |author-link=Ezra J. Warner (historian) |title=Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders |date=2006 |orig- |

* {{cite book |last=Warner |first=Ezra J. |author-link=Ezra J. Warner (historian) |title=Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders |date=2006 |orig-date=1964 |publisher=Louisiana State University Press |location=Baton Rouge, Louisiana |isbn=0-8071-3149-0}} |

||

[[Category:Body parts of individual people]] |

[[Category:Body parts of individual people|Sickles, Daniel]] |

||

[[Category:Daniel Sickles]] |

[[Category:Daniel Sickles|Leg]] |

||

[[Category:Battle of Gettysburg]] |

[[Category:Battle of Gettysburg|Leg, Sickles, Daniel]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Amputation|Sickles, Daniel]] |

||

[[Category:American Civil War medicine]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 23:53, 2 October 2024

The amputated right lower leg of Union Army general Daniel Sickles, lost after a cannonball wound suffered at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863, is displayed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Sickles was a former New York politician who entered the army after the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861. After originally commanding the Excelsior Brigade, Sickles was promoted to major general in 1862 and later commanded the III Corps at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, Sickles moved the III Corps forward from his assigned position, and it was shattered by a Confederate attack. During the fighting, he was struck in the leg by a solid shot; the wound later required amputation above the knee. After the amputation, the limb was donated to the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine), where it was used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma. Sickles sometimes visited the limb afterwards, and it remains a popular attraction at the museum.

Background

[edit]

Sickles was born on October 20, 1819, in New York City. He entered politics and served in the United States Congress from 1857 to 1861. In 1859, he gained notoriety for shooting[1] Philip Barton Key II over an affair Key had with Sickles's wife. Sickles successfully pleaded temporary insanity for the first time in United States history.[2] After the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, he joined the Union Army and was commissioned a brigadier general. Originally commanding the Excelsior Brigade, he was promoted to major general in November 1862, and commanded a division at the Battle of Fredericksburg and the III Corps at the Battle of Chancellorsville; he would also lead the III Corps at the Battle of Gettysburg.[3]

Leg wound and later display

[edit]

Early on July 2, 1863, with the Battle of Gettysburg ongoing, Sickles became concerned about the suitability of the position the III Corps was assigned to defend.[4] He later decided to abandon the position he had been assigned and moved his troops forward to another line along the Emmitsburg Road.[5] While this new position had some positive features, it was also exposed and the prior position had been adequate.[6] Confederate troops commanded by James Longstreet attacked Sickles's new position, and the III Corps was overrun.[7] With his line crumbling, Sickles rode up to the portion of III Corps at the Peach Orchard, which was falling apart. After watching the retreat of the 141st Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment, he headed towards the Trostle Farm.[8]

After riding onto a knoll for a better view of the fighting, Sickles was hit in the right leg by a 12-pound (5.4 kg) solid shot.[9] The shot did not startle Sickles's horse, and he dismounted and a tourniquet was applied to the wound. After transferring command of the III Corps to David B. Birney, Sickles was taken off the field on a stretcher while puffing on a cigar.[10] The injury had broken both of the bones (the tibia and the fibula) of his lower right leg.[11] The medical director of the III Corps, Thomas Sim, performed an amputation of Sickles's leg. It was initially thought that the cut could be made below the knee, but upon further inspection it was determined that the damage was more severe than first thought, and an amputation above the knee was required.[9] The general had been anesthetized with chloroform before the amputation.[12] After the limb was cut off, it was kept, possibly by Sim.[13]

Aware that the Army Medical Museum (since renamed the National Museum of Health and Medicine) had been recently founded, Sickles had the leg forwarded to the museum in a coffin-shaped box, as it had begun accumulating "specimens of morbid anatomy".[2] The damaged tibia and fibula were stabilized with wire and used as a museum specimen.[9] The bones were used as a teaching example of battlefield trauma.[11] Sickles recovered quickly from the wound,[2] but never held a field command again.[7] He sometimes visited the limb on the anniversary of its loss,[2] and sometimes brought visitors with him, including, on one occasion, Mark Twain who stated that he believed the general valued the lost leg more than his still-extant one.[9] Upon his first visit to the limb, Sickles allegedly berated the museum for not preserving his foot as well.[14] He retired from the army in 1869, was a diplomat to Spain, served another term in Congress, and died on May 3, 1914, at age 94.[7]

The leg bones have since been enclosed in a glass case[15] and have been reported as of 2014 to be one of the museum's most requested exhibits.[2] For a time in 2011, the bones were displayed at Fort Detrick,[11] but as of 2021 are again displayed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.[9] The bones are attached to a wooden stand by metal prongs and are displayed next to a cannonball of the type that caused the wound.[12]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Warner 2006, p. 446.

- ^ a b c d e Clarke 2014, p. 1051.

- ^ Warner 2006, pp. 446–447.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, pp. 95–97.

- ^ a b c Warner 2006, p. 447.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, p. 333.

- ^ a b c d e Pearlstein, Kristen (July 1, 2021). "Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles: His Contribution to the Army Medical Museum". National Museum of Health and Medicine. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, pp. 333–334.

- ^ a b c DeMetrick, Alex (May 7, 2011). "Civil War General's Leg on Display In Maryland". WJZ-TV. Archived from the original on 15 February 2022. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ a b Wheeler, Linda (July 12, 2001). "Union General Remained Attached to Museum Display of Amputated Limb". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, p. 334.

- ^ Hessler 2009, p. 315.

- ^ Pfanz 1987, p. 534 fn. 134.

Sources

[edit]- Clarke, Tim Jr. (2014). "Sickles' Leg and the Army Medical Museum". Military Medicine. 179 (8): 1051. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00182. PMID 25181725.

- Hessler, James A. (2009). Sickles at Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-84-5.

- Pfanz, Harry W. (1987). Gettysburg: The Second Day. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4730-5.

- Warner, Ezra J. (2006) [1964]. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3149-0.