Soybean: Difference between revisions

Panoptical (talk | contribs) ←Undid revision 110115675 by 165.138.163.5 (talk) |

Eithersummer (talk | contribs) m Fixed grammar Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App section source |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Legume grown for its edible bean}} |

|||

{{Taxobox |

|||

{{Redirect|Soy}} |

|||

| color = lightgreen |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

| name = Soybean |

|||

{{Use American English|date=September 2024}} |

|||

| image = Soybean.USDA.jpg |

|||

{{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=3}} |

|||

| image_width = 240px |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2020}} |

|||

| regnum = [[Plant]]ae |

|||

{{Speciesbox |

|||

| phylum = [[Flowering plant|Magnoliophyta]] |

|||

| image = Soybean.USDA.jpg |

|||

| classis = [[Magnoliopsida]] |

|||

| |

| genus = Glycine |

||

| species = max |

|||

| familia = [[Fabaceae]] |

|||

| authority = ([[Carl Linnaeus|L.]]) [[Elmer Drew Merrill|Merr.]] |

|||

| subfamilia = [[Faboideae]] |

|||

| synonyms = |

|||

| genus = ''[[Glycine (plant)|Glycine]]'' |

|||

* ''Dolichos soja'' <small>L.</small> |

|||

| species = '''''G. max''''' |

|||

* ''Glycine angustifolia'' <small>[[Friedrich Anton Wilhelm Miquel|Miq.]]</small> |

|||

| binomial = ''Glycine max'' |

|||

* ''Glycine gracilis'' <small>[[Boris Vassilievich Skvortsov|Skvortsov]]</small> |

|||

| binomial_authority = ([[Carolus Linnaeus|L.]]) [[Elmer Drew Merrill|Merr.]] |

|||

* ''Glycine hispida'' <small>([[Conrad Moench|Moench]]) [[Carl Maximowicz|Maxim.]]</small> |

|||

* ''Glycine soja'' <small>sensu [[auctorum|auct.]]</small> |

|||

* ''Phaseolus max'' <small>L.</small> |

|||

* ''Soja angustifolia'' <small>Miq.</small> |

|||

* ''Soja hispida'' <small>Moench</small> |

|||

* ''Soja japonica'' <small>[[Gaetano Savi|Savi]]</small> |

|||

* ''Soja max'' <small>([[Carl Linnaeus|L.]]) [[Charles Vancouver Piper|Piper]]</small> |

|||

* ''Soja soja'' <small>[[Gustav Karl Wilhelm Hermann Karsten|H. Karst.]]</small> |

|||

* ''Soja viridis'' <small>Savi</small> |

|||

| synonyms_ref = <ref name=eol>{{cite web |url=http://eol.org/pages/641527/overview |title=''Glycine max''|publisher=[[Encyclopedia of Life]] (EoL)|access-date=16 February 2012}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox Chinese |

|||

|c=大豆 |

|||

|l="large bean" |

|||

|p=dàdòu |

|||

|mi={{IPAc-cmn|d|a|4|.|d|ou|4}} |

|||

|altname=Southern Chinese name |

|||

|s2=黄豆 |

|||

|t2=黃豆 |

|||

|l2="yellow bean" |

|||

|p2=huángdòu |

|||

|j2=wong<sup>4</sup>-dau<sup>6</sup> |

|||

|y2=wòhng-dauh |

|||

|ci2={{IPAc-yue|w|ong|4|-|d|au|6}} |

|||

|h2=vòng-theu |

|||

|poj2=n̂g-tāu |

|||

|kanji=大豆<ref>Generally written in ''katakana'', not ''kanji''.</ref> |

|||

|kana=ダイズ |

|||

|romaji=daizu |

|||

|hanja=大豆 |

|||

|hangul=대두 (or 메주콩) |

|||

|rr=daedu (or mejukong) |

|||

|qn=đậu tương (or đỗ tương)<br />đậu nành |

|||

|chuhan=豆漿 |

|||

|chunom=豆𥢃 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''soybean''', '''soy bean''', or '''soya bean''' ('''''Glycine max''''')<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.plantnames.unimelb.edu.au/Sorting/Glycine.html#max |title=''Glycine max'' |publisher=[[Multilingual Multiscript Plant Name Database]] |access-date=16 February 2012}}</ref> is a species of [[legume]] native to [[East Asia]], widely grown for its edible [[bean]], which has numerous uses. |

|||

{{nutritionalvalue | name=Soybean, green raw | kJ=125.52 | protein=3.04 g | fat=0.18 g | satfat=0.046 g | monofat = 0.022 g | polyfat = 0.058 g| carbs=5.94 g | calcium_mg=13 | copper_mg = 0.164 | iron_mg=0.91 | magnesium_mg=21 | phosphorus_mg=54 | potassium_mg=149 | sodium_mg=6 | zinc_mg=0.41 | vitA_ug=1 | vitB6_mg=0.088 | vitB12_ug=0 | vitC_mg=13.2 | vitK_ug=33| water=90.4 g | fiber=1.8 g | sugars=4.13 g | right=1 | source_usda=1}} |

|||

Traditional unfermented food uses of soybeans include [[soy milk]], from which [[tofu]] and [[tofu skin]] are made. Fermented soy foods include [[soy sauce]], [[fermented bean paste]], [[nattō]], and [[tempeh]]. Fat-free (defatted) soybean meal is a significant and cheap source of protein for animal feeds and many [[TV dinner|packaged meals]].<ref name="rotundo">{{cite journal |vauthors=Rotundo JL, Marshall R, McCormick R, Truong SK, Styles D, Gerde JA, Gonzalez-Escobar E, Carmo-Silva E, Janes-Bassett V, Logue J, Annicchiarico P, de Visser C, Dind A, Dodd IC, Dye L, Long SP, Lopes MS, Pannecoucque J, Reckling M, Rushton J, Schmid N, Shield I, Signor M, Messina CD, Rufino MC |title=European soybean to benefit people and the environment |journal=Scientific Reports |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=7612 |date=March 2024 |pmid=38556523 |pmc=10982307 |doi=10.1038/s41598-024-57522-z|bibcode=2024NatSR..14.7612R }}</ref> For example, soybean products, such as [[textured vegetable protein]] (TVP), are ingredients in many meat and [[dairy]] substitutes.<ref name=rotundo/><ref name=Riaz2006>{{cite book |last=Riaz |first=Mian N. |title=Soy Applications in Food |publisher=CRC Press |location=Boca Raton, FL |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-8493-2981-4 }}</ref> |

|||

The '''soybean''' ([[American English|U.S.]]) or '''soya bean''' ([[British English|UK]]) (''Glycine max'') is a species of [[legume]] native to [[East Asia|Eastern Asia]]. It is an [[annual plant]] that may vary in growth, habit, and height. It may grow prostrate, not growing higher than 20 cm (7.8 inches), or even stiffly erect up to 2 meters (6.5 feet) in height. The pods, stems, and leaves are covered with fine brown,or gray, pubescence. The [[leaf|leaves]] are trifoliolate (sometimes with 5 leaflets), and the leaflets are 6-15 cm (2-6 inches) long and 2-7 cm (1-3 inches) broad. The leaves fall before the seeds are mature. The small, inconspicuous, self-fertile flowers are borne in the axil of the leaf and are white, pink or purple. The [[fruit]] is a hairy [[legume|pod]] that grows in clusters of 3-5, with each pod 3-8 cm (1-3 inches) long and usually containing 2-4 (rarely more) [[seed]]s 5-11 mm in diameter. |

|||

Soybeans contain significant amounts of [[phytic acid]], [[dietary minerals]] and [[B vitamins]]. [[Soybean oil|Soy vegetable oil]], used in food and industrial applications, is another product of processing the soybean crop. Soybean is a common protein source in feed for farm animals that in turn yield animal protein for human consumption.<ref name=rotundo/> |

|||

Like [[maize|corn]] and some other crops of long domestication, the relationship of the modern soybean to wild-growing species can no longer be traced with any degree of certainty. It is a cultural variety (a [[cultigen]]) with a very large number of [[cultivar]]s. However, it is known that the progenitor of the modern soybean was a vine-like plant, that grew prone on the ground. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

Beans are classed as [[pulses]] whereas soybeans are classed as [[oilseeds]]. The word soy is derived from the [[Japanese language|Japanese]] word 醤油 (''shoyu'') ([[soy sauce|soy sauce/soya sauce]]). |

|||

The word "soy" derives from the Japanese ''soi'', a regional variant of ''shōyu'', meaning "soy sauce".<ref>{{Cite OED|soy|6140796016}}</ref> |

|||

== Physical characteristics == |

|||

Soybeans occur in various sizes, and in several [[husk|hull]] or seed coat colors, including black, brown, blue, yellow, and mottled. The hull of the mature bean is hard, water resistant, and protects the [[cotyledon]] and [[hypocotyl]] (or "germ") from damage. If the seed coat is cracked the seed will not [[germinate]]. The scar, visible on the seed coat, is called the hilum (colors include black, brown, buff, gray and yellow) and at one end of the hilum is the micropyle, or small opening in the seed coat which can allow the absorption of water. |

|||

The name of the genus, ''Glycine'', comes from [[Carl Linnaeus|Linnaeus]]. When naming the genus, Linnaeus observed that one of the species within the genus had a sweet root. Based on the sweetness, the Greek word for sweet, ''glykós'', was Latinized.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last1=Hymowitz |first1=T. |last2=Newell |first2=C.A. |date=1981-07-01 |title=Taxonomy of the genus ''Glycine'', domestication and uses of soybeans |journal=[[Economic Botany]] |language=en |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=272–88 |doi=10.1007/BF02859119 |bibcode=1981EcBot..35..272H |s2cid=21509807 }}</ref> The genus name is not related to the amino acid [[glycine]].{{Citation needed|date=July 2021}} |

|||

It is a remarkable fact that seeds such as soybeans, containing very high levels of [[soy protein]], can undergo [[desiccation]] yet survive and revive after water absorption. A.Carl Leopold, son of [[Aldo Leopold]], set out twenty years ago to answer this very question at the [[Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research]] at [[Cornell University]]. Studying the survival of soybeans and corn he found each to have a range of soluble [[carbohydrate]]s protecting the seed's cell viability.<ref>{{cite journal | quotes = | last = Blackman | first = SA | authorlink = | coauthors = Obendorf RL, Leopold AC | date = | year = 1992 | month = Sept | title = Maturation Proteins and Sugars in Desiccation Tolerance of Developing Soybean Seeds | journal = Plant Physiol. | volume = 100 | issue = 1 | pages = 225-30 | doi = | id = {{PMC|1075542}} | url = http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1075542 | format = 1.2M PDF, or scanned pages | accessdate = 2006-10-21 }}</ref> Patents were awarded to him in the early 1990s on techniques for protecting "biological membranes" and proteins in the dry state. |

|||

==Description== |

|||

==Chemical composition of the seed== |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=July 2021}} |

|||

The oil and protein content together account for about 60% of dry soybeans by weight; protein at 40% and oil at 20%. The remainder consists of 35% carbohydrate and about 5% ash. Soybean cultivars comprise approximately 8% seed coat or hull, 90% [[cotyledons]] and 2% [[hypocotyl]] axis or germ. |

|||

Like most plants, soybeans grow in distinct [[Plant morphology|morphological]] stages as they develop from seeds into fully mature plants. |

|||

The majority of [[soy protein]] is a relatively heat-stable storage protein. It is this heat-stability of the soy protein that enables soy food products requiring high temperature cooking, such as [[tofu]], soymilk and textured vegetable protein (soy flour) to be made. |

|||

===Germination=== |

|||

The principal soluble [[carbohydrates]], saccharides, of mature soybeans are the disaccharide [[sucrose]](range 2.5-8.2%), the trisaccharide [[raffinose]]( 0.1-1.0%) composed of one sucrose molecule connected to one molecule of [[galactose]], and the tetrasaccharide [[stachyose]](1.4 to 4.1%) composed of one sucrose connected to two molecules of galactose. |

|||

The first stage of growth is [[germination]], a method which first becomes apparent as a seed's [[radicle]] emerges.<ref name=MP197Chapter2>{{cite book |last1=Purcell |first1=Larry C. |last2=Salmeron |first2=Montserrat |last3=Ashlock |first3=Lanny |title=Arkansas Soybean Production Handbook – MP197 |date=2014 |chapter=Chapter 2 |chapter-url=http://www.uaex.edu/publications/pdf/mp197/chapter2.pdf |publisher=University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service|location=Little Rock|pages=1–8 |url=http://www.uaex.edu/publications/mp-197.aspx |access-date=21 February 2016 |archive-date=March 4, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304011452/http://www.uaex.edu/publications/mp-197.aspx }}</ref> This is the first stage of root growth and occurs within the first 48 hours under ideal growing conditions. The first [[photosynthesis|photosynthetic]] structures, the [[cotyledon]]s, develop from the [[hypocotyl]], the first plant structure to emerge from the soil. These cotyledons both act as leaves and as a source of nutrients for the immature plant, providing the seedling nutrition for its first 7 to 10 days.<ref name=MP197Chapter2 /> |

|||

While the oligosaccharides raffinose and stachyose protect the viability of the soybean seed from desiccation{see above section on physical characteristics} they are not digestible sugars and therefore contribute to [[flatulence]] and abdominal discomfort in humans and other monogastric animals. Undigested oligosaccharides are broken down in the intestine by native microbes producing gases such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen, nitrogen, methane, etc. |

|||

[[File:Glycine max 003.JPG|thumb|Fruits/pods]] |

|||

Since soluble soy carbohydrates are found mainly in the [[whey]] and are broken down during fermentation, soy concentrate, [[soy protein]] isolates, [[tofu]], soy sauce, and sprouted soybeans are without flatus activity. On the other hand, there may be some beneficial effects to ingesting oligosaccharides such as raffinose and stachyose, namely, encouraging indigenous [[bifidobacteria]] in the colon against [[putrefactive]] bacteria. |

|||

===Maturation=== |

|||

The insoluble carbohydrates in soybeans consist of the complex polysaccharides [[cellulose]], [[hemicellulose]], and [[pectin]]. The majority of soybean carbohydrates can be classed as belonging to [[dietary fiber]]. |

|||

The first true leaves develop as a pair of [[Leaf#Divisions of the blade|single blades]].<ref name=MP197Chapter2 /> Subsequent to this first pair, mature [[Plant stem|nodes]] form compound leaves with three blades. Mature [[trifoliolate]] leaves, having three to four [[leaflet (botany)|leaflets]] per leaf, are often between {{convert|6|and|15|cm|in|frac=2|abbr=on}} long and {{convert|2|and|7|cm|in|frac=2|abbr=on}} broad. Under ideal conditions, stem growth continues, producing new nodes every four days. Before flowering, roots can grow {{convert|2|cm|in|frac=8|abbr=on}} per day. If [[rhizobia]] are present, [[root nodule|root nodulation]] begins by the time the third node appears. Nodulation typically continues for 8 weeks before the [[Rhizobia#Infection and signal exchange|symbiotic infection]] process stabilizes.<ref name=MP197Chapter2 /> The final characteristics of a soybean plant are variable, with factors such as genetics, [[soil quality]], and climate affecting its form; however, fully mature soybean plants are generally between {{convert|50|and|125|cm|in|-1|abbr=on}} in height<ref name=MP197Chapter19>{{cite book |last1=Purcell |first1=Larry C. |last2=Salmeron |first2=Montserrat |last3=Ashlock |first3=Lanny |title=Arkansas Soybean Production Handbook – MP197 |date=2000 |chapter=Chapter 19: Soybean Facts |chapter-url=http://www.uaex.edu/publications/pdf/mp197/chapter19.pdf |publisher=University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service |location=Little Rock, AR |page=1 |url=http://www.uaex.edu/publications/mp-197.aspx |access-date=5 September 2016 |archive-date=March 4, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304011452/http://www.uaex.edu/publications/mp-197.aspx }}</ref> and have rooting depths between {{convert|75|and|150|cm|in|-1|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bennett |first1=J. Michael |last2=Rhetoric |first2=Emeritus |last3=Hicks |first3=Dale R. |last4=Naeve |first4=Seth L. |last5=Bennett |first5=Nancy Bush |title=The Minnesota Soybean Field Book |date=2014 |publisher=[[University of Minnesota Extension]]|location=St Paul, MN |page=33 |url=http://www.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/soybean/docs/minnesota-soybean-field-book.pdf |access-date=16 September 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130930151502/http://www1.extension.umn.edu/agriculture/soybean/docs/minnesota-soybean-field-book.pdf |archive-date=September 30, 2013 }}</ref> |

|||

===Flowering=== |

|||

Flowering is [[Photoperiodism|triggered by day length]], often beginning once days become shorter than 12.8 hours.<ref name=MP197Chapter2 /> This trait is highly variable however, with different [[Variety (botany)|varieties]] reacting differently to changing day length.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Shurtleff |first1=William |author-link=William Shurtleff |last2=Aoyagi |first2=Akiko |author-link2=Akiko Aoyagi |title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland (1735–2015): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook |date=2015 |publisher=Soyinfo Center|location=Lafayette|isbn=978-1-928914-80-8 |page=490 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0gtpCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA490}}</ref> Soybeans form inconspicuous, self-fertile flowers which are borne in the [[axil]] of the leaf and are white, pink or purple. Though they do not require pollination, they are attractive to bees, because they produce nectar that is high in sugar content.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Reisig |first=Dominic |title=Soybean flowering, pollination, and bees |url=http://www.ncagr.gov/pollinators/documents/DominicReisig-NCPollinatorProtectionSoybeans.pdf |website=[[North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services]] |access-date=July 15, 2021 |archive-date=June 28, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210628160525/http://www.ncagr.gov/pollinators/documents/DominicReisig-NCPollinatorProtectionSoybeans.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> Depending on the soybean variety, node growth may cease once flowering begins. Strains that continue nodal development after flowering are termed "[[Indeterminate growth|indeterminates]]" and are best suited to climates with longer growing seasons.<ref name=MP197Chapter2 /> Often soybeans drop their leaves before the seeds are fully mature. |

|||

[[File:Soybean flowers.png|thumb|Small, purple flowers]] |

|||

The fruit is a hairy pod that grows in clusters of three to five, each pod is {{convert|3|–|8|cm|in|frac=2|abbr=on}} long and usually contains two to four (rarely more) [[seed]]s 5–11 mm in diameter. Soybean seeds come in a wide variety of sizes and [[husk|hull]] colors such as black, brown, yellow, and green.<ref name=MP197Chapter19 /> Variegated and bicolored seed coats are also common. |

|||

===Seed resilience=== |

|||

[[File:Soybeanvarieties.jpg|thumb|Bean varieties]] |

|||

The hull of the mature bean is hard, water-resistant, and protects the [[cotyledon]] and [[hypocotyl]] (or "germ") from damage. If the seed coat is cracked, the seed will not [[germinate]]. The scar, visible on the seed coat, is called the [[Hilum (biology)|hilum]] (colors include black, brown, buff, gray and yellow) and at one end of the hilum is the [[Micropyle (botany)|micropyle]], or small opening in the seed coat which can allow the absorption of water for sprouting. |

|||

Some seeds such as soybeans containing very high levels of [[soy protein|protein]] can undergo [[desiccation]], yet survive and revive after water absorption. [[A. Carl Leopold]] began studying this capability at the [[Boyce Thompson Institute for Plant Research]] at [[Cornell University]] in the mid-1980s. He found soybeans and corn to have a range of soluble [[carbohydrate]]s protecting the seed's cell viability.<ref>{{cite journal |pages=225–30 |doi=10.1104/pp.100.1.225 |title=Maturation Proteins and Sugars in Desiccation Tolerance of Developing Soybean Seeds |year=1992 |last1=Blackman |first1=S.A. |last2=Obendorf |first2=R.L. |last3=Leopold |first3=A.C. |journal=[[Plant Physiology (journal)|Plant Physiology]] |volume=100 |pmid=16652951 |issue=1 |pmc=1075542}}</ref> Patents were awarded to him in the early 1990s on techniques for protecting biological membranes and proteins in the dry state. |

|||

=== Chemistry === |

|||

Together, [[protein]] and [[soybean oil]] content account for 56% of dry soybeans by weight (36% protein and 20% [[fat]]. The remainder consists of 30% [[carbohydrate]]s, 9% water and 5% [[Ash (analytical chemistry)|ash]].<ref>See ''[[#Nutrition|Nutrition]]'' table</ref> Soybeans comprise approximately 8% seed coat or hull, 90% [[cotyledon]]s and 2% [[hypocotyl]] axis or germ.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Encyclopedia of Grain Science |last=Corke, Walker and Wrigley |publisher=[[Academic Press]] |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-12-765490-4}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=November 2015}} |

|||

== Taxonomy == |

|||

The genus ''Glycine'' may be divided into two subgenera, ''[[Glycine (subgenus)|Glycine]]'' and ''[[Soja (subgenus)|Soja]]''. The subgenus ''Soja'' includes the cultivated soybean, ''G. max'', and the wild soybean, treated either as a separate species ''[[Glycine soja|G. soja]]'',<ref name="SingNelsChun06">{{cite book |last1=Singh |first1=Ram J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lQ9bcjETlrIC&pg=PA15 |title=Genetic Resources, Chromosome Engineering, and Crop Improvement: Oilseed Crops, Volume 4 |last2=Nelson |first2=Randall L. |last3=Chung |first3=Gyuhwa |date=November 2, 2006 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-8493-3639-3 |location=[[London]] |page=15}}</ref> or as the subspecies ''G. max'' subsp. ''soja''.<ref name="POWO_920989-1">{{cite web |title=''Glycine max subsp. soja'' (Siebold & Zucc.) H.Ohashi |url=https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:920989-1 |access-date=2023-01-28 |work=Plants of the World Online |publisher=Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew}}</ref> The cultivated and wild soybeans are [[Annual plant|annuals]]. The wild soybean is native to [[China]], [[Japan]], [[Korea]] and [[Russia]].<ref name="SingNelsChun06" /> The subgenus ''Glycine'' consists of at least 25 wild [[perennial]] species: for example, ''[[Glycine canescens|G. canescens]]'' and ''[[Glycine tomentella|G. tomentella]]'', both found in [[Australia]] and [[Papua New Guinea]].<ref>{{cite conference |last=Hymowitz |first=Theodore |date=August 9, 1995 |editor-last=Sinclair |editor-first=J.B. |editor2-last=Hartman |editor2-first=G.L. |title=Evaluation of Wild Perennial ''Glycine'' Species and Crosses For Resistance to Phakopsora |location=[[Urbana, IL]], US |publisher=National Soybean Research Laboratory |pages=33–37 |book-title=Proceedings of the Soybean Rust Workshop}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Newell |first1=C.A. |last2=Hymowitz |first2=T. |date=March 1983 |title=Hybridization in the Genus ''Glycine'' Subgenus ''Glycine'' Willd. (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae) |journal=[[American Journal of Botany]] |volume=70 |issue=3 |pages=334–48 |doi=10.2307/2443241 |jstor=2443241}}</ref> Perennial soybean (''[[Neonotonia wightii]]'') belongs to a different genus. It originated in Africa and is now a widespread pasture crop in the tropics.<ref>Heuzé V., Tran G., Giger-Reverdin S., Lebas F., 2015. Perennial soybean (''Neonotonia wightii''). Feedipedia, a programme by [[Institut national de la recherche agronomique|INRA]], [[CIRAD]], Association Française de Zootechnie and [[FAO]]. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/293 Last updated on September 30, 2015, 15:09</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=''Neonotonia wightii'' in Global Plants on JSTOR |url=https://plants.jstor.org/compilation/Neonotonia.wightii |website=Global Plants on JSTOR}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Factsheet – ''Neonotonia wightii'' |url=http://www.tropicalforages.info/key/Forages/Media/Html/Neonotonia_wightii.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170601233037/http://tropicalforages.info/key/Forages/Media/Html/Neonotonia_wightii.htm |archive-date=June 1, 2017 |access-date=January 19, 2014 |work=tropicalforages.info}}</ref> |

|||

Like some other crops of long domestication, the relationship of the modern soybean to wild-growing species can no longer be traced with any degree of certainty.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Shekhar, Hossain |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H2m_DAAAQBAJ&q=the+relationship+of+the+modern+soybean+to+wild-growing+species+can+no+longer+be+traced+with+any+degree+of+certainty&pg=PA223 |title=Exploring the Nutrition and Health Benefits of Functional Foods |author2=Uddin, Howlader |author3=Zakir Hossain |author4=Kabir, Yearul |date=July 22, 2016 |publisher=IGI Global |isbn=978-1-5225-0592-1 |page=223 |access-date=22 November 2017}}</ref> It is a [[cultigen]] with a very large number of [[cultivar]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Ghulam Raza |author2=Mohan B. Singh |author3=Prem L. Bhalla |date=June 11, 2017 |editor1-last=Atanassov |editor1-first=Atanas |title=In Vitro Plant Regeneration from Commercial Cultivars of Soybean |journal=[[BioMed Research International]] |volume=2017 |page=7379693 |doi=10.1155/2017/7379693 |pmc=5485301 |pmid=28691031 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

== Ecology == |

|||

Like many legumes, soybeans can [[nitrogen fixation|fix atmospheric nitrogen]], due to the presence of [[symbiosis|symbiotic]] bacteria from the [[Rhizobia]] group.<ref>{{cite web |author=Jim Deacon |date=April 5, 2023 |title=The Nitrogen cycle and Nitrogen fixation |url=http://www.biology.ed.ac.uk/archive/jdeacon/microbes/nitrogen.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116214211/http://www.biology.ed.ac.uk/archive/jdeacon/microbes/nitrogen.htm |archive-date=January 16, 2013 |access-date=November 6, 2012 |publisher=Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Edinburgh}}</ref> |

|||

== Cultivation == |

|||

[[File:Soy beans.jpg|thumb|Soybean crops in [[Minnesota]]]] |

|||

[[File:AreialSeedingPlane.jpg|thumb|United States|alt=[[Biplane]], US field, [[cropduster|cropdusting]]]] |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=July 2021}} |

|||

===Conditions=== |

|||

[[File:Sembrado de soja en argentina.jpg|upright=1.2|thumb|[[Argentina]]|alt=Fields in [[Argentina]]]] |

|||

Cultivation is successful in climates with hot summers, with optimum growing conditions in mean temperatures of {{convert|20|to|30|C|F|round=5}}; temperatures of below {{convert|20|C|F|round=5}} and over {{convert|40|C|F|round=5}} stunt growth significantly. They can grow in a wide range of soils, with optimum growth in moist [[Alluvium|alluvial soil]]s with good organic content. Soybeans, like most legumes, perform [[nitrogen fixation]] by establishing a [[symbiotic]] relationship with the bacterium ''[[Bradyrhizobium japonicum]]'' ([[synonym (taxonomy)|syn.]] ''Rhizobium japonicum''; Jordan 1982). This ability to fix nitrogen allows farmers to reduce nitrogen [[fertilizer]] use and increase yields when growing other crops in [[Crop rotation|rotation]] with soy.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Corn and Soybean Rotation Effect - Wisconsin Corn Agronomy |url=http://corn.agronomy.wisc.edu/AA/A014.aspx |website=corn.agronomy.wisc.edu |access-date=2020-05-17 |archive-date=August 7, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200807071753/http://corn.agronomy.wisc.edu/AA/A014.aspx |url-status=dead }}</ref> There may be some trade-offs, however, in the long-term abundance of [[Soil organic matter|organic material in soils]] where soy and other crops (for example, [[Maize|corn]]) are grown in rotation.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Corn and soybean rotation could pose long-term tradeoffs for soil health |url=https://phys.org/news/2019-10-corn-soybean-rotation-pose-long-term.html |website=phys.org |language=en |access-date=2020-05-17}}</ref> For best results, though, an inoculum of the correct strain of bacteria should be mixed with the soybean (or any legume) seed before planting. Modern crop [[cultivar]]s generally reach a height of around {{convert|1|m|ft|0|abbr=on}}, and take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. |

|||

===Soils=== |

|||

Soil scientists [[Edson Lobato]] (Brazil), [[Andrew McClung]] (U.S.), and [[Alysson Paolinelli]] (Brazil) were awarded the 2006 [[World Food Prize]] for transforming the ecologically biodiverse savannah of the [[Cerrado]] region of Brazil into highly productive cropland that could grow profitable soybeans.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.worldfoodprize.org/en/laureates/20002009_laureates/2006_lobato_mcclung_paolinelli/|title=2006: Lobato, McClung, Paolinelli - The World Food Prize - Improving the Quality, Quantity and Availability of Food in the World|first=Global Reach Internet Productions, LLC-Ames, IA-|last=globalreach.com|website=www.worldfoodprize.org}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first = Susan|last = Lang|title = Cornell Alumnus Andrew Colin McClung Reaps 2006 World Food Prize|url = http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/June06/World.Food.prize.ssl.html|work =Chronicle Online |publisher = Cornell University|date = June 21, 2006|access-date =February 18, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://e360.yale.edu/feature/the_cerrado_brazils_other_biodiversity_hotspot_loses_ground/2393/ |title=The Cerrado: Brazil's Other Biodiverse Region Loses Ground|date=April 14, 2011|last=Pearce|first=Fred|publisher=Yale University|access-date=February 18, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.1023/A:1024191913296|title = The success of BNF in soybean in Brazil| journal=[[Plant and Soil]]| volume=252| pages=1–9|year = 2003|last1 = Alves|first1 = Bruno J.R.| last2=Boddey| first2=Robert M.| last3=Urquiaga| first3=Segundo| issue=1 | bibcode=2003PlSoi.252....1A |s2cid = 10143668}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Soybean rust.jpg|upright=0.9|thumb|[[Soybean rust]]]] |

|||

===Contamination concerns=== |

|||

Human [[sewage sludge]] can be used as fertilizer to grow soybeans. Soybeans grown in sewage sludge likely contain elevated concentrations of metals.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Molybdenum Uptake by Forage Crops Grown on Sewage Sludge-Amended Soils in the Field and Greenhouse|url=http://soilandwater.bee.cornell.edu/publications/McBrideJEQ00.pdf|journal=[[Journal of Environmental Quality]]|date=May–June 2000|volume=29|issue=3|last1=McBride|first1=M.B.|last2=Richards|first2=B.K.|last3=Steenhuis|first3=T.|last4=Spiers|first4=G.|pages=848–54|doi=10.2134/jeq2000.00472425002900030021x|bibcode=2000JEnvQ..29..848M }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Residual Effects of Sewage Sludge on Soybean: II. Accumulation of Soil and Symbiotically Fixed Nitrogen|journal=[[Journal of Environmental Quality]]|date=December 9, 1985|volume=16|issue=2|last1=Heckman|first1=J.R.|last2=Angle|first2=J.S.|last3=Chaney|first3=R.L.|pages=118–24|doi=10.2134/jeq1987.00472425001600020005x}}</ref> |

|||

===Pests=== |

|||

{{Further|List of soybean diseases}} |

|||

Soybean plants are vulnerable to a wide range of [[bacterial crop disease|bacterial diseases]], [[fungal crop disease|fungal diseases]], [[viral crop disease|viral diseases]], and parasites. |

|||

The primary bacterial diseases include [[bacterial blight]], [[bacterial pustule]] and [[downy mildew]] affecting the soybean plant.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://gardenandme.com/soybean/|title=Soybean plant - How to grow, care, pest control and uses of soybeans|date=June 5, 2020|website=Garden And Me}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Japanese beetle]] ('''''Popillia japonica''''') poses a significant threat to agricultural crops, including soybeans, due to its voracious feeding habits. Found commonly in both urban and suburban areas, these beetles are frequently observed in agricultural landscapes where they can cause considerable damage to crops like corn, soybeans, and various fruits. <ref>{{Cite web |title=Japanese beetle - Popillia japonica |url=https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/orn/beetles/japanese_beetle.htm |access-date=2024-04-25 |website=entnemdept.ufl.edu}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=EENY350/IN630: Japanese Beetle, Popillia japonica Newman (Insecta: Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) |url=https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN630 |access-date=2024-04-25 |website=Ask IFAS - Powered by EDIS |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

[[Soybean cyst nematode]] (SCN) is the worst pest of soybean in the US. Losses of 30%<ref name="Missouri" /> or 40%<ref group="RM" name="Tylka-40-sympt">"You can literally have 40% yield loss with no symptoms," says Greg Tylka, [[Iowa State University Extension|Iowa State University (ISU) Extension]] nematologist.</ref> are common even without symptoms. |

|||

The [[Helicoverpa zea|corn earworm moth and bollworm]] (Helicoverpa zea) is a common and destructive pest of soybean growth in Virginia.<ref>Herbert, Ames, Cathy Hull, and Eric Day. "Corn Earworm Biology and Management in Soybeans." [[Virginia Cooperative Extension]], [[Virginia State University]] (2009).</ref> |

|||

Soybeans are consumed by [[whitetail deer]] which may damage soybean plants through feeding, trampling and bedding, reducing [[crop yield]]s by as much as 15%.<ref name="ag">{{cite web|url=https://www.morningagclips.com/controlling-white-tailed-deer-in-soybeans|title=Controlling white-tailed deer in soybeans|date=16 January 2018|publisher=Morning AgClips – Michigan|access-date=9 May 2019}}</ref> [[Groundhog]]s are also a common pest in soybean fields, living in burrows underground and feeding nearby. One den of groundhogs can consume a tenth to a quarter of an acre of soybeans.<ref name="brant">{{cite web|url=https://www.lancasterfarming.com/news/columnists/soybean-farmers-warranted-in-waging-war-on-groundhogs/article_f6e6a210-2995-521f-8655-aa19efe373c3.html|title=Soybean Farmers Warranted in Waging War on Groundhogs|date=9 September 2016|publisher=[[Lancaster Farming]]|author=Brant, Jesse D|access-date=9 May 2019}}</ref> [[animal repellent|Chemical repellents]] or [[firearm]]s are effective for controlling pests in soybean fields.<ref name=ag/><ref name=brant/> |

|||

{{anchor|Fungi|Fungus|Funguses}} |

|||

Soybeans suffer from the fungus ''[[Pythium spinosum]]'' in [[Arkansas]] and [[Indiana]] (United States), and China.<ref name="P-spinosum-US-Nat-Fung-Coll">{{cite web |

|||

| title=U.S. National Fungus Collections Database results |

|||

| website=Fungal Databases, [[U.S. National Fungus Collections]] |

|||

| date=2020-12-08 |

|||

| url=http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/new_allViewGenBank.cfm?thisName=Pythium%20spinosum&organismtype=Fungus |

|||

| access-date=2020-12-08 |

|||

}}{{Dead link|date=November 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> |

|||

In Japan and the United States, the [[Soybean dwarf virus]] (SbDV) causes a disease in soybeans and is transmitted by aphids.<ref name="harrison2005">{{Cite journal |last1=Harrison |first1=Barbara |last2=Steinlage |first2=Todd A. |last3=Domier |first3=Leslie L. |last4=D'Arcy |first4=Cleora J. |date=January 2005 |title=Incidence of Soybean dwarf virus and Identification of Potential Vectors in Illinois |journal=Plant Disease |language=en |volume=89 |issue=1 |pages=28–32 |doi=10.1094/PD-89-0028 |doi-access=free |pmid=30795280 |issn=0191-2917 }}</ref> |

|||

===Cultivars=== |

|||

====Disease resistant cultivars==== |

|||

[[plant disease resistance|Resistant varieties]] are available. In Indian cultivars, Nataraj ''et al.'' 2020 find that anthracnose caused by ''[[Colletotrichum truncatum]]'' is resisted by a combination of 2 major genes.<ref name="identification">{{Cite journal|issue=4|pages=393–409|year=2021|volume=22|last1=Boufleur|first1=Thais R.|last2=Ciampi-Guillardi|first2=Maisa|last3=Tikami|first3=Ísis|last4=Rogério|first4=Flávia|last5=Thon|first5=Michael R.|last6=Sukno|first6=Serenella A.|last7=Massola Júnior|first7=Nelson S.|last8=Baroncelli|first8=Riccardo|journal=[[Molecular Plant Pathology]]|s2cid=231969160|pmid=33609073|pmc=7938629|doi=10.1111/mpp.13036|title=Soybean anthracnose caused by ''Colletotrichum'' species: Current status and future prospects}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|issue=6|volume=67|year=2020|last1=Nataraj|first1=Vennampally|last2=Maranna|first2=Shivakumar|last3=Kumawat|first3=Giriraj|last4=Gupta|first4=Sanjay|last5=Rajput|first5=Laxman Singh|last6=Kumar|first6=Sanjeev|last7=Sharma|first7=Amar Nath|last8=Bhatia|first8=Virender Singh|journal=Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution|s2cid=211730576|doi=10.1007/s10722-020-00917-4|pages=1449–1456|title=Genetic inheritance and identification of germplasm sources for anthracnose resistance in soybean [''Glycine max'' (L.) Merr.]}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

=====PI 88788===== |

|||

The vast majority of cultivars in the US have [[soybean cyst nematode resistance]] (SCN resistance), but rely on [[soybean cyst nematode#PI 88788|only one breeding line (PI 88788)]] as their sole source of resistance.<ref group="RM" name="PI-88788">Reliance on the main genetic source of SCN resistance (PI 88788)may be helping SCN to overcome SCN-resistant varieties. Out of 807 resistant varieties listed by ISU this year, just 18 had a genetic background outside of PI 88788. "We have lots of varieties to pick from, but the genetic background is not as diverse as we would like it to be," says Tylka.</ref> (The resistance genes provided by PI 88788, {{Visible anchor|Peking}}, and {{Visible anchor|PI 90763}} were [[genome mapping|characterized]] in 1997.)<ref name="Concibido-et-al-1997">{{cite journal|issue=1|last1=Concibido|first1=Vergel C.|last2=Lange|first2=Douglas A.|last3=Denny|first3=Roxanne L.|last4=Orf|first4=James H.|last5=Young|first5=Nevin D.|title=Genome Mapping of Soybean Cyst Nematode Resistance Genes in 'Peking', PI 90763, and PI 88788 Using DNA Markers|journal=[[Crop Science (journal)|Crop Science]]|volume=37|year=1997|doi=10.2135/cropsci1997.0011183x003700010046x|pages=258–264}}</ref> As a result, for example, in 2012 only 18 cultivars out of 807 recommended by the [[Iowa State University Extension]] had any ancestry outside of PI 88788. By 2020 the situation was still about the same: Of 849 there were 810 with some ancestry from PI 88788,<ref name="Iowa-other-resist">{{cite web | title=Soybean varieties with SCN resistance other than PI 88788 | website=Integrated Crop Management | publisher=[[Iowa State University#Birth of cooperative extension|Iowa State University Extension]] | url=http://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2020/12/soybean-varieties-scn-resistance-other-pi-88788 | access-date=2021-03-12}}</ref><ref name="Iowa-resist">{{cite web | title=SCN-resistant Soybean Varieties for Iowa - By the Numbers | website=Integrated Crop Management | publisher=[[Iowa State University#Birth of cooperative extension|Iowa State University Extension]] | url=http://crops.extension.iastate.edu/cropnews/2020/11/scn-resistant-soybean-varieties-iowa-numbers | access-date=2021-03-12}}</ref> 35 from Peking, and only 2 from PI 89772. (On the question of exclusively PI 88788 ancestry, that number was not available for 2020.)<ref name="Iowa-resist" /> That was speculated to be in 2012<ref group="RM" name="overcome-resis">There have been cases where SCN has clipped yields of SCN-resistant varieties. Reliance on the main genetic source of SCN resistance (PI 88788)may be helping SCN to overcome SCN-resistant varieties.</ref>—and was clearly by 2020<ref name="Iowa-other-resist" />—producing SCN populations that are virulent on PI 88788. |

|||

=== Production === |

|||

{{main|List of countries by soybean production}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; clear:left; width:18em; text-align:center;" |

|||

! colspan=2|Soybean production – 2020 |

|||

|- |

|||

! style="background:#ddf; width:75%;"| Country |

|||

! style="background:#ddf; width:25%;"| <small>Production (millions of [[tonne]]s)</small> |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{BRA}} ||122 |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{USA}} ||113 |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{ARG}} ||49 |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{CHN}} ||20 |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{IND}} ||11 |

|||

|- |

|||

| {{PAR}} ||11 |

|||

|- |

|||

| '''World'''||'''353''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan="2" style="text-align: center;" | <small>Source: [[Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database|FAOSTAT]]<ref name="faostat19">{{cite web|publisher=United Nations, Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division, FAOSTAT|title=Soybean production in 2019, Crops/World regions/Production quantity (from pick lists)|url=http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/|access-date=8 February 2021|date=2019}}</ref></small> |

|||

|} |

|||

[[File:PRODUCTION OF SOYBEANS (2018).svg|thumb|<ref name="FAO-2020-production-map" />|alt=Production of soybeans (2018)<ref name="FAO-2020-production-map">{{Cite book|title=World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2020|publisher=[[FAO]]|year=2020|isbn=978-92-5-133394-5|location=[[Rome]]|doi=10.4060/cb1329en|s2cid=242794287}}</ref>]] |

|||

In 2020, world production of soybeans was over 353 million tonnes, led by Brazil and the United States combined with 66% of the total (table). Production has dramatically increased across the globe since the 1960s, but particularly in South America after a cultivar that grew well in low latitudes was developed in the 1980s.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Cattelan|first1=Alexandre José|last2=Dall'Agnol|first2=Amélio|date=2018-01-01|title=The rapid soybean growth in Brazil|url=https://www.ocl-journal.org/articles/ocl/abs/2018/01/ocl170039/ocl170039.html|journal=[[OCL (journal)|OCL]]|language=en|volume=25|issue=1|pages=D102|doi=10.1051/ocl/2017058|doi-access=free}}</ref> The rapid growth of the industry has been primarily fueled by large increases in [[Western pattern diet|worldwide demand for meat]] products, particularly in developing countries like China, which alone accounts for more than 60% of imports.<ref>{{Cite web|title=OEC - Soybeans (HS92: 1201) Product Trade, Exporters and Importers|url=https://oec.world/en/profile/hs92/1201/|website=oec.world|language=en|access-date=2020-05-17|archive-date=April 4, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200404122328/https://oec.world/en/profile/hs92/1201/|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

==== Environmental issues ==== |

|||

{{Seealso|Deforestation of the Amazon rainforest}} |

|||

In spite of the Amazon "Soy Moratorium", soy production continues to play a significant role in [[deforestation]] when its indirect impacts are taken into account, as land used to grow soy continues to increase. This land either comes from [[pasture]] land (which increasingly supplants forested areas), or areas outside the Amazon not covered by the moratorium, such as the [[Cerrado]] region. Roughly one-fifth of deforestation can be attributed to expanding land use to produce oilseeds, primarily for soy and [[palm oil]], whereas the expansion of [[beef]] production accounts for 41%. The main driver of deforestation is the global demand for meat, which in turn requires huge tracts of land to grow feed crops for livestock.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://ourworldindata.org/drivers-of-deforestation |title=Drivers of Deforestation |last=Ritchie |first=Hannah |author1-link=Hannah Ritchie |date= February 9, 2021|journal=[[Our World in Data]] |access-date=March 20, 2021 }}</ref> Around 80% of the global soybean crop is used to feed livestock.<ref>{{cite news |last= Liotta|first= Edoardo|date=August 23, 2019 |title=Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat|url=https://www.vice.com/en_in/article/bjwzk4/feeling-sad-about-the-amazon-fires-stop-eating-meat |work=[[Vice Media|Vice]] |access-date=August 25, 2019|quote=Soy is the most important protein in animal feed, with 80 percent of the world's soybean crop fed to livestock.}}</ref> |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=July 2021}} |

|||

Soybeans were a crucial crop in East Asia long before written records began.<ref>Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko. 2013. History of Whole Dry Soybeans, Used as Beans, or Ground, Mashed or Flaked (240 BCE to 2013). Lafayette, California. 950 pp.</ref> The origin of soy bean cultivation remains scientifically debated. The closest living relative of the soybean is ''[[Glycine soja]]'' (previously called ''G. ussuriensis''), a legume native to central China.<ref name=britannica>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/557184/soybean |title=Soybean |encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] Online |access-date=February 18, 2012}}</ref> There is evidence for soybean domestication between 7000 and 6600 BC in China, between 5000 and 3000 BC in Japan and 1000 BC in Korea.<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011">{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Gyoung-Ah |last2=Crawford |first2=Gary W. |last3=Liu |first3=Li |last4=Sasaki |first4=Yuka |last5=Chen |first5=Xuexiang |title=Archaeological Soybean (''Glycine max'') in East Asia: Does Size Matter? |journal=[[PLOS ONE]] |date=November 4, 2011 |volume=6 |issue=11 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0026720 |pages=e26720 |pmid=22073186 |pmc=3208558|bibcode=2011PLoSO...626720L |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

The first unambiguously domesticated, [[cultigen]]-sized soybean was discovered in Korea at the [[Mumun pottery period|Mumun]]-period Daundong site.<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /><ref name="Stark-2017">{{cite book|last1=Stark|first1=Miriam T.|title=Archaeology of Asia|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-4051-5303-4|page=81|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z4_bT2SJ-HUC&pg=PA81|access-date=18 April 2017|language=en|date=15 April 2008}}</ref> Prior to [[Fermentation (food)|fermented]] products such as fermented black soybeans (''[[douchi]]''), ''jiang'' (Chinese miso), [[soy sauce]], [[tempeh]], [[nattō]], and [[miso]], soy was considered sacred for its beneficial effects in [[crop rotation]], and it was eaten by itself, and as [[bean curd]] and [[soy milk]]. |

|||

Soybeans were introduced to [[Java]] in [[Malay Archipelago]] circa 13th century or probably earlier. By the 17th century through their trade with Far East, soybeans and its products were traded by European traders (Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch) in Asia, and reached Indian Subcontinent by this period.{{citation needed|date=July 2022}} By the 18th century, soybeans were introduced to the Americas and Europe from China. Soy was introduced to Africa from China in the late 19th century, and is now widespread across the continent. |

|||

===East Asia=== |

|||

[[File:Leiden University Library - Seikei Zusetsu vol. 18, page 023 - 穭豆 - Glycine max (L.) Merr., 1804.jpg|thumb|''[[Seikei Zusetsu]]'' (1804)|alt=[[Botanical illustration]], ''[[Seikei Zusetsu]]'' (1804)]] |

|||

The cultivation of soybeans began in the eastern half of northern China by 2000 BC, but is almost certainly much older.<ref name=Murphy>{{cite book |title=People, Plants and Genes: The Story of Crops and Humanity |url=https://archive.org/details/peopleplantsgene00murp_652 |url-access=limited |location=New York |publisher=Oxford University Press |pages=[https://archive.org/details/peopleplantsgene00murp_652/page/n146 122]–123 |year=2007 |last= Murphy |first= Denis J.}}</ref> The earliest documented evidence for the use of ''Glycine'' of any kind comes from charred plant remains of wild soybean recovered from Jiahu in [[Henan province]] China, a [[Neolithic]] site occupied between 9000 and 7800 calendar years ago (cal bp).<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /> An abundance of archeological charred soybean specimens have been found centered around this region.<ref>Zhao Z. 2004. "Floatation: a paleobotanic method in field archaeology". [[Archaeology (journal)|Archaeology]] 3: 80–87.</ref> |

|||

According to the ancient Chinese myth, in 2853 BC, the legendary [[Shennong|Emperor Shennong]] of China proclaimed that five plants were sacred: soybeans, rice, wheat, barley, and [[millet]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.soya.be/history-of-soybeans.php|title=History of Soybeans|publisher=Soya – Information about Soy and Soya Products|access-date=February 18, 2012}}</ref> Early Chinese records mention that soybeans were a gift from the region of [[Yangtze River delta]] and Southeast China.<ref name="Britannica Educational Publishing p. 48">The History of Agriculture By Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 48</ref> The ''[[Great Soviet Encyclopedia]]'' claims soybean cultivation originated in China about 5000 years ago.<ref>''[[Great Soviet Encyclopedia]]'', ed. A. M. Prokhorov (New York: Macmillan, London: Collier Macmillan, 1974–1983) 31 volumes, three volumes of indexes. Translation of third Russian edition of ''Bol'shaya Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya''</ref> Some scholars suggest that soybean originated in China and was domesticated about 3500 BC.<ref name=Siddiqi>{{cite book |last=Siddiqi |first=Mohammad Rafiq |year=2001 |title=Tylenchida: Parasites of Plants and Insects |location=New York |publisher=CABI Pub.}}</ref> Recent research, however, indicates that seeding of wild forms started early (before 5000 BC) in multiple locations throughout East Asia.<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /> |

|||

Soybeans became an important crop by the Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BC) in China. However, the details of where, when, and under what circumstances soybean developed a close relationship with people are poorly understood. Soybean was unknown in South China before the Han period.<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /> From about the first century AD to the [[Age of Discovery]] (15–16th centuries), soybeans were introduced into across South and Southeast Asia. This spread was due to the establishment of sea and land trade routes. The earliest Japanese textual reference to the soybean is in the classic ''[[Kojiki]]'' (''Records of Ancient Matters''), which was completed in AD 712. |

|||

The oldest preserved soybeans resembling modern varieties in size and shape were found in [[archaeological site]]s in [[Korea]] dated about 1000 BC.<ref name="Britannica Educational Publishing p. 48"/><ref name=stark>{{cite book |last=Stark|first=Miriam T. |title=Archaeology of Asia (Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology) |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |location=Hoboken, NJ |year=2005 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PoDFdOstSNwC&pg=PA81|page=81|isbn=978-1-4051-0213-1|access-date=February 18, 2012}}</ref> [[Radiocarbon dating]] of soybean samples recovered through [[flotation (archaeology)|flotation]] during excavations at the Early [[Mumun]] period Okbang site in Korea indicated soybean was cultivated as a food crop in around 1000–900 BC.<ref name=stark /> Soybeans from the Jōmon period in Japan from 3000 BC<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /> are also significantly larger than wild varieties.<ref name="Lee-et-al-2011" /><ref>Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko. 2012. ''History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Japan''. Lafayette, California.</ref> |

|||

===Southeast Asia=== |

|||

Soybeans were mentioned as ''kadêlê'' (modern [[Indonesian language|Indonesian]] term: {{Lang|id|kedelai}})<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/indonesian-english/kedelai|title=kedelai translate Indonesian to English: Cambridge Dictionary|website=dictionary.cambridge.org|language=en|access-date=2018-01-21}}</ref> in an [[old Javanese]] manuscript, Serat [[Sri Tanjung]], which dates to 12th- to 13th-century [[Java]].<ref name="Historia">{{cite web | title=Sejarah Tempe| author=Hendri F. Isnaeni | date=9 July 2014| publisher=Historia |url=http://historia.id/kuliner/sejarah-tempe | language=id | access-date= 21 January 2018}}</ref> By the 13th century, the soybean had arrived and cultivated in Indonesia; it probably arrived much earlier however, carried by traders or merchants from Southern China.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/139|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Southeast Asia (1770–2010)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|isbn=978-1-928914-30-3|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi|year=2010}}</ref> |

|||

The earliest known reference to it as "[[tempeh]]" appeared in 1815 in the [[Serat Centhini]] manuscript.<ref>''The Book of Tempeh'', 2nd ed., by W. Shurtleff and A. Aoyagi (2001, Ten Speed Press, p. 145)</ref> The development of tempeh fermented soybean cake probably took place earlier, circa 17th century in Java. |

|||

===Indian subcontinent=== |

|||

By the 1600s, soy sauce spread from southern Japan across the region through the [[Dutch East India Company]] (VOC). |

|||

[[File:Soya Bean.jpg|thumb|From a high-altitude area of [[Nepal]]]] |

|||

[[File:Soyabean field.jpg|thumb|[[India]]|alt=Field in India]] |

|||

While the origins and history of Soybean cultivation in the [[Eastern Himalayas]] is debated, it was potentially introduced from southern [[China]], more specifically [[Yunnan]] province.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Shurtleff |first1=William |url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/140 |title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in South Asia / Indian Subcontinent (1656–2010) |last2=Aoyagi |first2=Akiko |publisher=Soy Info Center |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-928914-31-0 |access-date=February 18, 2012}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Tamang |first=Jyoti Prakash |date=September 2024 |title=Unveiling kinema: blending tradition and science in the Himalayan fermented soya delicacy |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=29 |doi=10.1186/s42779-024-00247-1 |doi-access=free |issn=2352-619X}}</ref> Alternatively, it could have reached here through traders from [[Indonesia]] via [[Myanmar]]. [[Northeast India]] is viewed as a passive micro-centre within the soybean secondary gene centre. Central India is considered a tertiary gene centre particularly the area encompassing Madhya Pradesh which is also the country largest soybean producer.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

===Iberia=== |

|||

In 1603, "[[Nippo Jisho|Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam]]", a famous Japanese-Portuguese dictionary, was compiled and published by Jesuit priests in Nagasaki. It contains short but clear definitions for about 20 words related to soyfoods—the first in any European language. |

|||

The Luso-Hispanic traders were familiar with soybeans and soybean product through their trade with Far East since at least the 17th century. However, it was not until the late 19th century that the first attempt to cultivate soybeans in the Iberian peninsula was undertaken. In 1880, the soybean was first cultivated in Portugal in the [[Botanical Garden of the University of Coimbra|Botanical Gardens at Coimbra]] (Crespi 1935). |

|||

In about 1910 in Spain the first attempts at Soybean cultivation were made by the Count of San Bernardo, who cultivated soybeans on his estates at Almillo (in southwest Spain) about 48 miles east-northeast of Seville.<ref>Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A. 2015. "History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Spain and Portugal (1603–2015)." Lafayette, California: Soyinfo Center. (624 references; 23 photos and illustrations. Free online.)</ref> |

|||

===North America=== |

|||

Soybeans were first introduced to North America from China in 1765, by [[Samuel Bowen]], a former [[East India Company]] sailor who had visited China in conjunction with [[James Flint (merchant)|James Flint]], the first Englishman legally permitted by the Chinese authorities to learn Chinese.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| title = An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730–1815 |

|||

| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=_I0_gkKKMM8C&pg=PA147 |

|||

| last1 = Chaplin |

|||

| first1 = J.E. |

|||

| year = 1996 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-8078-4613-1 |

|||

| publisher = University of North Carolina Press |

|||

| page = 147}}</ref> The first "New World" soybean crop was grown on [[Skidaway Island, Georgia]], in 1765 by Henry Yonge from seeds given him by Samuel Bowen.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Hymowitz|first=T.|date=1970-10-01|title=On the domestication of the soybean|journal=[[Economic Botany]]|language=en|volume=24|issue=4|pages=408–21|doi=10.1007/BF02860745|bibcode=1970EcBot..24..408H |s2cid=26735964|url=http://elartu.tntu.edu.ua/handle/lib/43629 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.caes.uga.edu/extension/irwin/anr/Vol29.1.pdf.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923195804/http://www.caes.uga.edu/extension/irwin/anr/Vol29.1.pdf.pdf |archive-date=September 23, 2015 |publisher=Georgia Soybean News |website=caes.uga.edu |title=Another First for Georgia Agriculture |author=Roger Boerma |page=5 |volume=1 |issue=1 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=360&dat=19940831&id=9eMyAAAAIBAJ&pg=6901,2669493&hl=en|publisher=The Rockmart Journal|title=Soybeans planted first in Georgia|date=21 August 1994|website=Google News Archive}}</ref> Bowen grew soy near [[Savannah, Georgia]], possibly using funds from Flint, and made soy sauce for sale to England.<ref name="Coastalfields Press">{{cite book|title=Eat Your Food! Gastronomical Glory from Garden to Gut: A Coastalfields Cookbook, Nutrition Textbook, Farming Manual and Sports Manual|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BtZ2oNGyv6AC&pg=PR2|access-date=4 May 2013|date=April 2007|publisher=Coastalfields Press|isbn=978-0-9785944-8-0}}</ref> Although soybean was introduced into North America in 1765, for the next 155 years, the crop was grown primarily for [[forage]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nsrl.uiuc.edu/aboutsoy/history4.html |title=About Soy - Soybeans: The Success Story - p.4|date=November 22, 2003 |website=National Soybean Research Laboratory - [[University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign]] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031122134643/http://www.nsrl.uiuc.edu/aboutsoy/history4.html |archive-date=November 22, 2003 }}</ref> |

|||

In 1831, the first soy product "a few dozen India Soy" [sauce] arrived in Canada. Soybeans were probably first cultivated in Canada by 1855, and definitely in 1895 at [[Ontario Agricultural College]].<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/137|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Canada (1831–2010)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|isbn=978-1-928914-28-0|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi|year=2010}}</ref> |

|||

It was not until [[Lafayette Mendel]] and [[Thomas Burr Osborne (chemist)|Thomas Burr Osborne]] showed that the nutritional value of soybean seeds could be increased by cooking, moisture or heat, that soy went from a farm animal feed to a human food.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.aces.uiuc.edu/vista/html_pubs/irspsm91/kunitz.html|title=The Kunitz Soybean Variety|work=uiuc.edu|date=2018-02-20|first = Theodore|last =Hymowitz}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://cropsci.illinois.edu/news/scientists-create-new-low-allergen-soybean|title= Scientists create new low-allergen soybean|work=illinois.edu|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150605195117/http://cropsci.illinois.edu/news/scientists-create-new-low-allergen-soybean|archive-date=June 5, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

William Morse is considered the "father" of modern soybean agriculture in America. In 1910, he and [[Charles Piper]] (Dr. C. V. Piper) began to popularize what was regarded as a relatively unknown Oriental peasant crop in America into a "golden bean", with the soybean becoming one of America's largest and most nutritious farm crops.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/HSS/morse_and_piper.php|title=William J. Morse and Charles V. Piper|work=soyinfocenter.com|first1= William |last1=Shurtleff |first2=Akiko|last2= Aoyagi|date =2004}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/147|title=William J. Morse – History of His Work with Soybeans and Soyfoods (1884–1959) – SoyInfo Center |publisher=soyinfocenter.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Piper |first1=Charles V. |author1-link=Charles Piper |last2=Morse |first2=William J. |year=1923 |title=The Soybean |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6hRCAAAAYAAJ |series=Agricultural and Biological Publications |location=New York |publisher=McGraw-Hill Book Company |oclc=252589754 |via=Google Books}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Soybeans 2021 US map.pdf|frameless|alt=Planted area 2021 US map by state|left|upright=2.0]] |

|||

Prior to the 1920s in the US, the soybean was mainly a [[forage]] crop, a source of oil, meal (for feed) and industrial products, with very little used as food. However, it took on an important role after World War I. During the [[Great Depression]], the drought-stricken ([[Dust Bowl]]) regions of the United States were able to use soy to regenerate their soil because of its nitrogen-fixing properties. Farms were increasing production to meet with government demands, and [[Henry Ford]] became a promoter of soybeans.<ref name=":3">{{Cite news|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-12-07/history-of-soybeans-in-u-s-could-take-turn-in-trump-s-trade-war?srnd=premium|title=How Soybeans Became Ubiquitous |newspaper=Bloomberg.com |date=December 7, 2019 |publisher=Bloomberg News |access-date=2019-12-07}}</ref> In 1931, Ford hired chemists [[Robert Boyer (chemist)|Robert Boyer]] and Frank Calvert to produce [[artificial silk]]. They succeeded in making a textile fiber of spun soy protein fibers, hardened or tanned in a [[formaldehyde]] bath, which was given the name [[Azlon]]. It never reached the commercial market. Soybean oil was used by [[Ford Motor Company|Ford]] in [[Soy paint|paint]] for the automobiles,<ref name="Schwarcz">{{cite book |author=Joe Schwarcz|title=The Fly in the Ointment: 63 Fascinating Commentaries on the Science of Everyday Life |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rmIbClRzfeoC&pg=PA193 |access-date=4 May 2013 |year=2004 |publisher=ECW Press |isbn=978-1-55022-621-8|page=193}}</ref> as well as a fluid for shock absorbers. |

|||

During World War II, soybeans became important in both North America and Europe chiefly as substitutes for other protein foods and as a source of edible oil. During the war, the soybean was discovered as [[fertilizer]] due to [[nitrogen fixation]] by the [[United States Department of Agriculture]]. |

|||

Prior to the 1970s, Asian-Americans and Seventh-Day Adventists were essentially the only users of soy foods in the United States.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Roth |first=Matthew |year=2018 |title=Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America |location=Lawrence, KS |publisher=University Press of Kansas|page=109 |isbn=978-0-7006-2633-5 |oclc=1012618664 }}</ref> "The soy foods movement began in small pockets of the counterculture, notably the Tennessee commune named simply [[The Farm (Tennessee)|The Farm]], but by the mid-1970s a vegetarian revival helped it gain momentum and even popular awareness through books such as [[William Shurtleff|''The Book of Tofu'']]."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Roth |first=Matthew |year=2018 |title=Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America |location=Lawrence, KS |publisher=University Press of Kansas|page=201 |isbn=978-0-7006-2633-5 |oclc=1012618664 }}</ref> |

|||

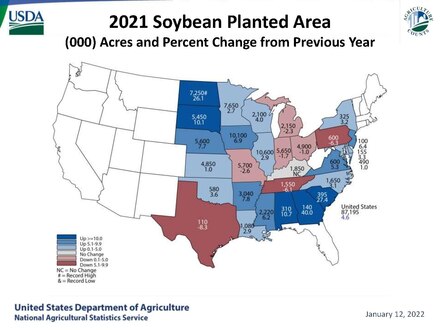

Although practically unseen in 1900, by 2000 soybean plantings covered more than 70 million acres,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Roth |first=Matthew |year=2018 |title=Magic Bean: The Rise of Soy in America |location=Lawrence, KS |publisher=University Press of Kansas|page=8 |isbn=978-0-7006-2633-5 |oclc=1012618664 }}</ref> second only to corn, and it became America's largest cash crop.{{citation needed|date=February 2022}} In 2021, 87,195,000 acres were planted, with the largest acreage in the states of Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota.<ref>{{cite web |title=2021 Soybean Planted Area (000) Acres and Percent Change from Previous Year |url=https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/graphics/soyacm.pdf |website=USDA-National Agricultural Statistics Service |publisher=USDA |access-date=4 February 2022 |date=12 January 2022}}</ref> |

|||

===Caribbean and West Indies=== |

|||

The soybean arrived in the Caribbean in the form of soy sauce made by Samuel Bowen in Savannah, Georgia, in 1767. It remains only a minor crop there, but its uses for human food are growing steadily.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/126|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in the Caribbean / West Indies (1767–2008)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi}}</ref> |

|||

===Mediterranean area=== |

|||

The soybean was first cultivated in Italy by 1760 in the Botanical Garden of Turin. During the 1780s, it was grown in at least three other botanical gardens in Italy.<ref>Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A. (2015). ''History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Italy (1597–2015)''. Lafayette, California: Soyinfo Center. 618 pp. (1,381 references; 93 photos and illustrations. Free online.)</ref> The first soybean product, soy oil, arrived in [[Anatolia]] during 1909 under [[Ottoman Empire]].<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=urb6IPmxwU8C&q=soybean+turkey&pg=PA7|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in the Middle East: Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook|last1=Shurtleff|first1=William|last2=Aoyagi|first2=Akiko|date=2008|publisher=Soyinfo Center|isbn=978-1-928914-15-0|language=en}}</ref> The first clear cultivation occurred in 1931.<ref name=":2" /> This was also the first time that soybeans were cultivated in Middle East.<ref name=":2" /> By 1939, soybeans were cultivated in Greece.<ref>Matagrin. 1939. "Le Soja et les Industries du Soja," p. 47–48</ref><ref>Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A. 2015. "History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Greece, the European Union and Small Western European Countries (1939–2015)." Lafayette, California: Soyinfo Center. 243 pp. (462 references; 20 photos and illustrations. Free online. {{ISBN|978-1-928914-81-5}}).</ref> |

|||

===Australia=== |

|||

Wild soybeans were discovered in northeastern Australia in 1770 by explorers Banks and Solander. In 1804, the first soyfood product ("Fine India Soy" [sauce]) was sold in Sydney. In 1879, the first domesticated soybeans arrived in Australia, a gift of the Minister of the Interior Department, Japan.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/138|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Australia, New Zealand and Oceania (1770–2010)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|isbn=978-1-928914-29-7|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi|year=2010}}</ref> |

|||

===France=== |

|||

The soybean was first cultivated in France by 1779 (and perhaps as early as 1740). The two key early people and organizations introducing the soybean to France were the Society of Acclimatization (starting in 1855) and [[Li Shizeng|Li Yu-ying]] (from 1910). Li started a large tofu factory, where the first commercial soyfoods in France were made.<ref>Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A.; 2015. "History of Soybeans and Soyfood in France (1665–2015)". Lafayette, California; Soyinfo Center. 1,202 pp. (3,405 references; 145 photos and illustrations. Free online).</ref> |

|||

===Africa=== |

|||

The soybean first arrived in Africa via Egypt in 1857.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/134|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Africa (1857–2009)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|isbn=978-1-928914-25-9|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi|date=2009}}</ref> Soya Meme (Baked Soya) is produced in the village called Bame Awudome near [[Ho, Ghana|Ho]], the capital of the [[Volta Region]] of [[Ghana]], by the [[Ewe people]] of Southeastern Ghana and southern Togo. |

|||

===Central Europe=== |

|||

In 1873, Professor [[Friedrich J. Haberlandt]] first became interested in soybeans when he obtained the seeds of 19 soybean varieties at the [[Vienna World Exposition]] (Wiener Weltausstellung). He cultivated these seeds in Vienna, and soon began to distribute them throughout Central and Western Europe. In 1875, he first grew the soybeans in Vienna, then in early 1876 he sent samples of seeds to seven cooperators in central Europe, who planted and tested the seeds in the spring of 1876, with good or fairly good results in each case.<ref name="shurtleff">Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi, A. 2015. "History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Austria and Switzerland (1781–2015)." Lafayette, California: Soyinfo Center. 705 pp. (1444 references; 128 photos and illustrations). Free online. {{ISBN|978-1-928914-77-8}}.</ref> Most of the farmers who received seeds from him cultivated them, then reported their results. Starting in February 1876, he published these results first in various journal articles, and finally in his ''magnum opus'', Die Sojabohne (The Soybean) in 1878.<ref name=shurtleff/> In northern Europe, [[lupin]] (lupine) is known as the "soybean of the north".<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/17/business/energy-environment/soy-substitute-edges-its-way-into-european-meals.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0|title=Soy Substitute Edges Its Way Into European Meals|last=Ross|first=Kate|newspaper=New York Times|date=November 16, 2011|access-date=February 28, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

===Central Asia=== |

|||

The soybean is first in cultivated Transcaucasia in Central Asia in 1876, by the Dungans. This region has never been important for soybean production.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/123|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Central Asia (1876–2008)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi}}</ref> |

|||

===Central America=== |

|||

The first reliable reference to the soybean in this region dates from Mexico in 1877.<ref name=book-128>{{cite web|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/128|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in Mexico and Central America (1877–2009)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi}}</ref> |

|||

===South America=== |

|||

The soybean first arrived in South America in Argentina in 1882.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.soyinfocenter.com/books/132|title=History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in South America (1882–2009)|publisher=Soy Info Center|access-date=February 18, 2012|isbn=978-1-928914-23-5|first1=William|last1=Shurtleff|first2=Akiko|last2=Aoyagi|year=2009}}</ref> |

|||

Andrew McClung showed in the early 1950s that with soil amendments the [[Cerrado]] region of Brazil would grow soybeans.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.news.cornell.edu/stories/2006/06/cornellian-reaps-2006-world-food-prize|title=Cornell alumnus Andrew Colin McClung reaps 2006 World Food Prize|publisher=news.cornell.edu – Cornell Chronicle}}</ref> In June 1973, when soybean futures markets mistakenly portended a major shortage, the [[Presidency of Richard Nixon|Nixon administration]] imposed an embargo on soybean exports. It lasted only a week, but Japanese buyers felt that they could not rely on U.S. supplies, and the rival Brazilian soybean industry came into existence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.agpolicy.org/weekcol/217.html|title=Policy Pennings, by Daryll E. Ray, Agricultural Policy Analysis Center|website=www.agpolicy.org|access-date=2019-12-07}}</ref><ref name=":3" /> This led Brazil to become the world's largest producer of soybeans in 2020, with 131 million tons.<ref>[https://revistagloborural.globo.com/Noticias/Agricultura/noticia/2020/06/brasil-deve-colher-131-milhoes-de-toneladas-de-soja-na-safra-202021-aponta-usda.html Brasil deve colher 131 milhões de toneladas de soja na safra 2020/21, aponta USDA]</ref> |

|||

Industrial soy production in South America is characterized by wealthy management who live far away from the production site which they manage remotely. In Brazil, these managers depend heavily on advanced technology and machinery, and agronomic practices such as zero tillage, high pesticide use, and intense fertilization. One contributing factor is the increased attention on the Brazilian [[Cerrado]] in [[Bahia]], Brazil by US farmers in the early 2000s. This was due to rising values of scarce farmland and high production costs in the US Midwest. There were many promotions of the Brazilian Cerrado by US farm producer magazines and market consultants who portrayed it as having cheap land with ideal production conditions, with infrastructure being the only thing it was lacking. These same magazines also presented Brazilian soy as inevitably out-competing American soy. Another draw to investing was the insider information about the climate and market in Brazil. A few dozen American farmers purchased varying amounts of land by a variety of means including finding investors and selling off land holdings. Many followed the [[Ethanol fuel|ethanol]] company model and formed an [[Limited liability company|LLC]] with investments from neighboring farmers, friends, and family while some turned to investment companies. Some soy farmers either [[Liquidation|liquidated]] their Brazilian assets or switched to remote management from the US to return to farming there and implement new farming and business practices to make their US farms more productive. Others planned to sell their now expensive Bahia land to buy land cheaper land in the frontier regions of [[Piauí]] or [[Tocantins]] to create more soybean farms.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ofstehage |first=Andrew L. |date=2018-05-10 |title=Financialization of work, value, and social organization among transnational soy farmers in the Brazilian Cerrado |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/sea2.12123 |journal=Economic Anthropology |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=274–285 |doi=10.1002/sea2.12123 |issn=2330-4847}}</ref> |

|||

==Genetics== |

|||

Chinese [[landrace]]s were found to have a slightly higher genetic diversity than inbred lines by Li ''et al.'', 2010.<ref name="Hinze-et-al-2017" /> Specific locus amplified fragment sequencing (SLAF-seq) has been used by Han ''et al.'', 2015 to study the genetic history of the [[crop domestication|domestication process]], perform [[genome-wide association study|genome-wide association studies]] (GWAS) of [[agronomic trait|agronomically relevant traits]], and produce [[high-density linkage map]]s.<ref name="Rasheed-et-al-2017">{{cite journal | last1=Rasheed | first1=Awais | last2=Hao | first2=Yuanfeng | last3=Xia | first3=Xianchun | last4=Khan | first4=Awais | last5=Xu | first5=Yunbi | last6=Varshney | first6=Rajeev K. | last7=He | first7=Zhonghu | title=Crop Breeding Chips and Genotyping Platforms: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives | journal=[[Molecular Plant]] | volume=10 | issue=8 | year=2017 | doi=10.1016/j.molp.2017.06.008 | pages=1047–1064 | s2cid=33780984 | pmid=28669791| doi-access=free }}</ref> An [[SNP array]] was developed by Song ''et al.'', 2013 and has been used for research and [[crop breeding|breeding]];<ref name="Hulse-Kemp-et-al-2015">{{cite journal | last1=Hulse-Kemp | first1=Amanda M|last2=Lemm | first2=Jana | last3=Plieske | first3=Joerg | last4=Ashrafi | first4=Hamid | last5=Buyyarapu | first5=Ramesh | last6=Fang | first6=David D | last7=Frelichowski | first7=James | last8=Giband | first8=Marc | last9=Hague | first9=Steve | last10=Hinze | first10=Lori L | last11=Kochan | first11=Kelli J | last12=Riggs | first12=Penny K | last13=Scheffler | first13=Jodi A | last14=Udall | first14=Joshua A | last15=Ulloa | first15=Mauricio | last16=Wang | first16=Shirley S | last17=Zhu | first17=Qian-Hao | last18=Bag | first18=Sumit K | last19=Bhardwaj | first19=Archana | last20=Burke | first20=John J | last21=Byers | first21=Robert L | last22=Claverie | first22=Michel | last23=Gore | first23=Michael A | last24=Harker | first24=David B | last25=Islam | first25=Mohammad Sariful | last26=Jenkins | first26=Johnie N | last27=Jones | first27=Don C | last28=Lacape | first28=Jean-Marc | last29=Llewellyn | first29=Danny J | last30=Percy | first30=Richard G | last31=Pepper | first31=Alan E | last32=Poland | first32=Jesse A | last33=Mohan Rai | first33=Krishan | last34=Sawant | first34=Samir V | last35=Singh | first35=Sunil Kumar | last36=Spriggs | first36=Andrew | last37=Taylor | first37=Jen M | last38=Wang | first38=Fei | last39=Yourstone | first39=Scott M | last40=Zheng | first40=Xiuting | last41=Lawley | first41=Cindy T | last42=Ganal | first42=Martin W | last43=Van Deynze | first43=Allen | last44=Wilson | first44=Iain W | last45=Stelly | first45=David M | title=Development of a 63K SNP Array for Cotton and High-Density Mapping of Intraspecific and Interspecific Populations of ''Gossypium'' spp. | journal=G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics | volume=5 | issue=6 | date=2015-06-01 | doi=10.1534/g3.115.018416 | pages=1187–1209 | pmid=25908569 | pmc=4478548 | s2cid=11590488}}</ref> the same team applied their array in Song ''et al.'', 2015 against the USDA Soybean Germplasm Collection and obtained mapping data that are expected to yield [[association mapping]] data for such traits.<ref name="Hinze-et-al-2017">{{cite journal|last1=Hinze | first1=Lori L. | last2=Hulse-Kemp | first2=Amanda M. | last3=Wilson | first3=Iain W. | last4=Zhu | first4=Qian-Hao | last5=Llewellyn | first5=Danny J. | last6=Taylor | first6=Jen M. | last7=Spriggs | first7=Andrew | last8=Fang | first8=David D. | last9=Ulloa | first9=Mauricio | last10=Burke | first10=John J. | last11=Giband | first11=Marc | last12=Lacape | first12=Jean-Marc | last13=Van Deynze | first13=Allen | last14=Udall | first14=Joshua A. | last15=Scheffler | first15=Jodi A. | last16=Hague | first16=Steve | last17=Wendel | first17=Jonathan F. | last18=Pepper | first18=Alan E. | last19=Frelichowski | first19=James | last20=Lawley | first20=Cindy T. | last21=Jones | first21=Don C. | last22=Percy | first22=Richard G. | last23=Stelly | first23=David M. | title=Diversity analysis of cotton (''Gossypium hirsutum'' L.) germplasm using the CottonSNP63K Array | journal=BMC Plant Biology | volume=17 | issue=1 | date=2017-02-03 | page=37 | doi=10.1186/s12870-017-0981-y | pmid=28158969 | pmc=5291959 | s2cid=3969205 | doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

{{Vanchor|Rpp1-R1}} is a [[crop fungal disease resistance gene|resistance gene]] against [[soybean rust]].<ref name="Show-Me-Your-ID" /> Rpp1-R1 is an [[R gene]] (NB-LRR) providing resistance against the rust pathogen ''[[Phakopsora pachyrhizi]]''.<ref name="Show-Me-Your-ID" /> Its synthesis product includes a [[ULP1 protease]].<ref name="Show-Me-Your-ID"> |

|||

{{ Cite journal |

|||

| doi=10.1042/ebc20210084 |

|||

| pmc=9528084 |

|||

| pmid=35635051 |

|||

| title=Show me your ID: NLR immune receptors with integrated domains in plants |

|||

| date=2022 |

|||

| last1=Marchal |

|||

| first1=Clemence |

|||

| last2=Michalopoulou |

|||

| first2=Vassiliki A. |

|||