Museo del Prado: Difference between revisions

ce opening to reflect npov and removed promotion |

No edit summary |

||

| (81 intermediate revisions by 46 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description| |

{{short description|National art museum in Madrid, Spain}} |

||

{{redirect|Prado}} |

{{redirect|Prado}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Multiple issues| |

|||

{{Copy edit|date=July 2022|for=being needlessly promotional. Needs to be rewritten as an encyclopaedia article}} |

|||

{{Peacock|date=July 2022}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|date=July 2022}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2015}} |

|||

{{WikidataCoord}} |

|||

{{Infobox museum |

{{Infobox museum |

||

| name = Museo Nacional del Prado |

| name = Museo Nacional del Prado |

||

| image = |

| image = Museo del Prado 2016 (25185969599).jpg |

||

| caption = Front façade (Velázquez entrance) in 2016 |

|||

| image_size = 270px |

|||

| caption = Exterior of the Prado Museum |

|||

| mapframe-zoom = 16 |

| mapframe-zoom = 16 |

||

| established = 1819 |

| established = {{start date|1819|11|19|df=y}} |

||

| dissolved = |

| dissolved = |

||

| location = Paseo del Prado, [[Madrid]], |

| location = [[Paseo del Prado]], [[Madrid]], Spain |

||

| type = [[Art museum]], [[ |

| type = [[Art museum]], [[historic site]] |

||

| visitors = 3,337,550 (2023)<ref>{{Cite web |title=El Museo Nacional del Prado ha recibido 3.337.550 visitas en 2023 |url=https://www.museodelprado.es/actualidad/noticia/el-museo-nacional-del-prado-ha-recibido-3337550/b55843d0-7f92-d776-e29b-e217004f4716 |access-date=2 September 2024 |website=museodelprado.es |publisher=Museo Del Prado |archive-date=23 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240523231209/https://www.museodelprado.es/actualidad/noticia/el-museo-nacional-del-prado-ha-recibido-3337550/b55843d0-7f92-d776-e29b-e217004f4716 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[List of most-visited art museums|Ranked 13th globally]] (2023)<ref name="Art Newspaper data">{{Cite web |last=Cheshire |first=Lee |last2=da Silva |first2=José |date=27 March 2023 |title=The 100 most popular art museums in the world—who has recovered and who is still struggling? |url=https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/03/27/the-100-most-popular-art-museums-in-the-worldwho-has-recovered-and-who-is-still-struggling |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230328204505/https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/03/27/the-100-most-popular-art-museums-in-the-worldwho-has-recovered-and-who-is-still-struggling |archive-date=28 March 2023 |access-date=8 July 2023 |website=[[The Art Newspaper]]}}</ref> |

|||

| visitors = 852,161 (2020)<ref>''[[The Art Newspaper]]'', Marc h 31,2021 </ref><br/>[[List of most-visited art museums|Ranked 16th globally]] (2020)<ref name="worldranking">[http://www.museus.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/TheArtNewspaper2013_ranking.pdf Top 100 Art Museum Attendance], ''[[The Art Newspaper]]'', 2014. Retrieved on 15 July 2014.</ref> |

|||

| director = Miguel Falomir<ref>{{Cite web |last=Barrigós, Concha |date=21 March 2017 |title=Miguel Falomir, nuevo director del Prado: "Nunca, nunca pediré el traslado del 'Guernica'" |url=http://www.20minutos.es/noticia/2991133/0/miguel-falomir-nuevo-director-museo-prado/ |access-date=1 April 2017 |publisher=[[20 minutos]] |archive-date=16 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221016094032/https://www.20minutos.es/noticia/2991133/0/miguel-falomir-nuevo-director-museo-prado/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| director = Miguel Falomir<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| publictransit = {{plainlist| |

|||

| url=http://www.20minutos.es/noticia/2991133/0/miguel-falomir-nuevo-director-museo-prado/ |

|||

* [[Banco de España (Madrid Metro)|Banco de España]] {{rint|madrid|metro}} {{rint|madrid|2}} |

|||

| title=Miguel Falomir, nuevo director del Prado: "Nunca, nunca pediré el traslado del 'Guernica'" |

|||

* [[Estación del Arte (Madrid Metro)|Estación del Arte]] {{rint|madrid|metro}} {{rint|madrid|1}} }} |

|||

| access-date=1 April 2017 |

|||

|website = {{URL|https://www.museodelprado.es/en|museodelprado.es}} |

|||

| author=Barrigós, Concha |

|||

| logo= Logo del Museo Nacional del Prado.png |

|||

| date=21 March 2017 |

|||

| logo_size= 270px |

|||

| publisher=[[20 minutos]] |

|||

| map_type= |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

| former_name= |

|||

|publictransit = *[[Madrid Atocha railway station|Atocha Main Line Station]] |

|||

| embedded = |

|||

*[[Banco de España (Madrid Metro)|Banco de España Underground Station]] |

|||

|website = [http://www.museodelprado.es www.museodelprado.es] |

|||

|logo=[[File:Logo del Museo Nacional del Prado.png|270px]]|map_type=|former_name= |

|||

| embedded = |

|||

{{Infobox historic site |

{{Infobox historic site |

||

| embed = yes |

| embed = yes |

||

| name = |

| name = |

||

| native_name = |

| native_name = |

||

| native_language = |

| native_language = |

||

| locmapin = |

|||

|image = Museo del Prado 2016 (25185969599).jpg |

|||

|caption = Museo del Prado (front [[façade]]) |

|||

| locmapin = |

|||

| location = |

| location = |

||

| area = |

| area = |

||

| built = |

| built = |

||

| architect = [[Juan de Villanueva]] |

| architect = [[Juan de Villanueva]] |

||

| architecture = |

| architecture = |

||

| governing_body = |

| governing_body = |

||

| designation1 = Spain |

| designation1 = Spain |

||

| designation1_offname = Museo Nacional del Prado |

| designation1_offname = Museo Nacional del Prado |

||

| Line 55: | Line 43: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Museo |

The '''Museo del Prado''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|p|r|ɑː|d|oʊ}} {{respell|PRAH|doh}}; {{IPA|es|muˈseo ðel ˈpɾaðo}}), officially known as '''Museo Nacional del Prado''', is the main Spanish national [[art museum]], located in central [[Madrid]]. It houses collections of [[Art of Europe|European art]], dating from the 12th century to the early 20th century, based on the former [[Spanish royal collection]], and the single best collection of [[Spanish art]]. Founded as a museum of [[painting]]s and [[sculpture]] in 1819, it also contains important collections of other types of works. The numerous works by [[Francisco Goya]], the single most extensively represented artist, as well as by [[Hieronymus Bosch]], [[El Greco]], [[Peter Paul Rubens]], [[Titian]], and [[Diego Velázquez]], are some of the highlights of the collection. Velázquez and his keen eye and sensibility were also responsible for bringing much of the museum's fine collection of Italian masters to Spain, now one of the largest outside of Italy. |

||

The collection currently comprises around 8,200 drawings, 7,600 paintings, 4,800 prints, and 1,000 sculptures, in addition to many other works of art and historic documents. As of 2012, the museum displayed about 1,300 works in the main buildings, while around 3,100 works were on temporary loan to various museums and official institutions. The remainder were in storage.<ref name="collection">{{Cite web |title=The Collection: origins |url=http://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/origins/ |access-date=15 November 2012 |publisher=Museo Nacional del Prado |archive-date=13 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150913013530/https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/origins/ |url-status=dead }}See also ''Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas'', 1996, Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid, No ISBN, which lists about 7,800 paintings. Many works have been passed to the Museo Reina Sofia and other museums over the years; others are on loan or in storage. On the new displays, see [http://www.europapress.es/cultura/noticia-museo-prado-reordena-agranda-20090302171352.html El Prado se reordena y agranda. europapress.es here (in Spanish)] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006081332/http://www.europapress.es/cultura/noticia-museo-prado-reordena-agranda-20090302171352.html |date=6 October 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

The Museo del Prado has a collection of approximately 8,200 drawings, 8,600 paintings, 4,800 prints, and 1,000 sculptures and displays around 1,300 at any time, while roughly 3,100 are lent on temporary loan. Due to the [[COVID-19 pandemic]], attendance in 2020 dropped 76 percent to 852,161. Nonetheless, the Prado was ranked as the [[list of most-visited art museums|16th most-visited art museum]] in the world in 2020.<ref>"The Art Newspaper", 31 march 2021</ref> |

|||

Due to the [[COVID-19 pandemic]], in 2020 attendance plunged by 76 percent to 852,161. Nonetheless, the Prado was ranked as the 16th most-visited museum in the [[list of most-visited art museums]] in the world in 2020.<ref>"The Art Newspaper", 31 March 2021</ref> It is one of the [[list of largest art museums|largest]] museums in Spain. |

|||

The Prado, with the nearby [[Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum]] and the [[Museo Reina Sofía]], forms part of the Madrid's [[Golden Triangle of Art]]. |

|||

The Prado and the nearby [[Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum]] and the [[Museo Reina Sofía]] form Madrid's Golden Triangle of Art along the [[Paseo del Prado]], which was included in the [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage]] list in 2021. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The building that is now the home of the Museo Nacional del Prado was designed in 1785 by architect of the [[Enlightenment in Spain]] [[Juan de Villanueva]] on the orders of [[Charles III of Spain|Charles III]] to house the Natural History Cabinet. Nonetheless, the building's final function was not decided until the monarch's grandson, [[Ferdinand VII]], encouraged by his wife, Queen [[Maria Isabel of Portugal|María Isabel de Braganza]], decided to use it as a new Royal Museum of Paintings and Sculptures. The |

The building that is now the home of the ''Museo Nacional del Prado'' was designed in 1785 by architect of the [[Enlightenment in Spain]] [[Juan de Villanueva]] on the orders of [[Charles III of Spain|Charles III]] to house the Natural History Cabinet. Nonetheless, the building's final function was not decided until the monarch's grandson, [[Ferdinand VII]], encouraged by his wife, Queen [[Maria Isabel of Portugal|María Isabel de Braganza]], decided to use it as a new Royal Museum of Paintings and Sculptures. The royal museum, which would soon become known as the National Museum of Painting and Sculpture, and subsequently the Museo Nacional del Prado, opened to the public for the first time in November 1819. It was created with the double aim of showing the [[Spanish royal collection|works of art belonging to the Spanish Crown]] and to demonstrate to the rest of Europe that Spanish art was of equal merit to any other national school. Also, this museum needed several renovations during the 19th and 20th centuries, because of the increase of the collection as well as the increase of the public who wants to see all the collection that the museum hosted.<ref>{{Cite web |date=13 November 2020 |title=La historia del Museo del Prado |url=https://www.vipealo.com/blog/la-historia-del-museo-del-prado/ |access-date=13 November 2020 |website=Vipealo |archive-date=22 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201122075923/https://www.vipealo.com/blog/la-historia-del-museo-del-prado/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

[[File:Grand hall d'exposition au Musée du Prado.JPG|thumb|left |

[[File:Grand hall d'exposition au Musée du Prado.JPG|thumb|left|In the main exhibition hall, first floor]] |

||

The first catalogue of the |

The first catalogue of the museum, published in 1819 and solely devoted to Spanish painting, included 311 paintings, although at that time the museum housed 1,510 from the various royal residences, the Reales Sitios, including works from other schools. The exceptionally important royal collection, which forms the nucleus of the present-day {{lang|es|Museo del Prado}}, started to increase significantly in the 16th century during the time of [[Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor|Charles V]] and continued under the succeeding Habsburg and Bourbon monarchs. Their efforts and determination led to the royal collection being enriched by some of the masterpieces now to be seen in the Prado. These include ''[[The Descent from the Cross (van der Weyden)]]'' by [[Rogier van der Weyden]], ''[[The Garden of Earthly Delights]]'' by [[Hieronymous Bosch]], ''[[The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest]]'' by [[El Greco]], ''[[Death of the Virgin (Mantegna)]]'' by [[Andrea Mantegna|Mantegna]], ''The Holy Family'', known as "[[La Perla (painting)]]", by [[Raphael]], ''[[Equestrian Portrait of Charles V]]'' by [[Titian]], ''[[The Washing of the Feet|Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet]]'' by [[Tintoretto]], [[Dürer]]'s ''[[Self-portrait at 26]]'', ''[[Las Meninas]]'' by Velázquez, ''[[The Three Graces (Rubens, Madrid)|The Three Graces]]'' by Rubens, and ''[[The Family of Charles IV]]'' by Goya.{{fact|date=August 2020}} |

||

{{multiple image |

{{multiple image |

||

| Line 71: | Line 61: | ||

| width = 220 |

| width = 220 |

||

| header = [[Francisco Goya]] |

| header = [[Francisco Goya]] |

||

| image1 =Goya Maja naga2.jpg |

| image1 = Goya Maja naga2.jpg |

||

| alt1 = |

| alt1 = |

||

| caption1 = |

| caption1 = {{Lang|es|[[La maja desnuda]]}}, oil on canvas, ({{Circa|1797–1800}}) |

||

| image2 = Goya Maja ubrana2.jpg |

| image2 = Goya Maja ubrana2.jpg |

||

| alt2 = |

| alt2 = |

||

| caption2 = |

| caption2 = {{Lang|es|[[La maja vestida]]}}, oil on canvas, ({{Circa|1797–1800}}) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

In addition to works from the [[Spanish royal collection]], other holdings increased and enriched the |

In addition to works from the [[Spanish royal collection]], the other holdings increased and enriched the museum with further masterpieces, such as the two Majas by Goya. Among the now closed museums whose collections have been added to that of the Prado were the [[Museo de la Trinidad]] in 1872, and the [[Museo de Arte Moderno (Madrid)|Museo de Arte Moderno]] in 1971. In addition, numerous legacies, donations and purchases have been of crucial importance for the growth of the collection. Various works entered the Prado from the Museo de la Trinidad, including ''The Fountain of Grace'' by the School of Van Eyck, the Santo Domingo and San Pedro Martír altarpieces painted for the monastery of Santo Tomás in Ávila by [[Pedro Berruguete]], and the [[Doña María de Aragón Altarpiece|five canvases]] by El Greco executed for the Colegio de doña María de Aragón. Most of the Museum's 19th-century paintings come from the former Museo de Arte Moderno, including works by the Madrazos, [[José de Madrazo y Agudo]] and [[Federico de Madrazo]], [[Vicente López Portaña|Vicente López]], [[Carlos de Haes]], [[Eduardo Rosales]] and [[Sorolla]].{{fact|date=August 2020}} |

||

Upon the deposition of [[Isabella II of Spain|Isabella II]] in 1868, the museum was nationalized and acquired the new name of "Museo del Prado". The building housed the royal collection of arts, and it rapidly proved too small. The first enlargement to the museum took place in 1918. Since the creation of the Museo del Prado more than 2,300 paintings have been incorporated into its collection, as well as numerous sculptures, prints, drawings and works of art through bequests, donations and purchases, which account for most of the New Acquisitions. Numerous bequests have enriched the |

Upon the deposition of [[Isabella II of Spain|Isabella II]] in 1868, the museum was nationalized and acquired the new name of "{{lang|es|Museo del Prado|italic=no}}". The building housed the royal collection of arts, and it rapidly proved too small. The first enlargement to the museum took place in 1918. Since the creation of the {{lang|es|Museo del Prado}} more than 2,300 paintings have been incorporated into its collection, as well as numerous sculptures, prints, drawings and works of art through bequests, donations and purchases, which account for most of the New Acquisitions. Numerous bequests have enriched the museum's holdings, such as the outstanding collection of medals left to the museum by Pablo Bosch; the drawings and items of decorative art left by Pedro Fernández Durán as well as [[Van der Weyden]]'s masterpiece, ''[[Duran Madonna]]''; and the Ramón de Errazu bequest of 19th-century paintings. Particularly important donations include Barón Emile d'Erlanger's gift of Goya's Black Paintings in 1881. Among the numerous works that have entered the collection through purchase are some outstanding ones acquired in recent years including two works by El Greco, ''The Fable'' and ''The Flight into Egypt'' acquired in 1993 and 2001, Goya's ''[[The Countess of Chinchon]]'' bought in 2000, Velázquez's ''Portrait of Ferdinando Brandani'', acquired in 2003, Bruegel's ''[[The Wine of Saint Martin's Day]]'' bought in 2010 and Fra Angelico's ''Madonna of the Pomegranate'' purchased in 2016.{{fact|date=August 2020}} |

||

[[File:Velázquez en El Prado.JPG|left|thumb|upright|[[Statue of Velázquez (Madrid)|Statue of Diego Velázquez]] by [[Aniceto Marinas]] (1899), dominating the Velázquez entrance.]] |

|||

Between 1873 and 1900, the Prado helped decorate city halls, new universities, and churches. During the [[Second Spanish Republic]] from 1931 to 1936, the focus was on developing provincial museums. During the [[Spanish Civil War]], upon the recommendation of the [[League of Nations]], the museum staff removed 353 paintings, 168 drawings and the Dauphin's Treasure and sent the art to [[Valencia (city in Spain)|Valencia]], then later to [[Girona]], and finally to [[Geneva]]. The art had to be returned across French territory in night trains to the museum upon the commencement of World War II. During the early years of the dictatorship of [[Francisco Franco]], many paintings were sent to embassies.<ref name="riding">{{ |

Between 1873 and 1900, the Prado helped decorate city halls, new universities, and churches. During the [[Second Spanish Republic]] from 1931 to 1936, the focus was on developing provincial museums. During the [[Spanish Civil War]], upon the recommendation of the [[League of Nations]], the museum staff removed 353 paintings, 168 drawings and the Dauphin's Treasure and sent the art to [[Valencia (city in Spain)|Valencia]], then later to [[Girona]], and finally to [[Geneva]]. The art had to be returned across French territory in night trains to the museum upon the commencement of World War II. During the early years of the dictatorship of [[Francisco Franco]], many paintings were sent to embassies.<ref name="riding">{{Cite news |last=Alan Riding |date=1 August 1990 |title=The Prado Finds Out What It Has and Where |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/01/arts/the-prado-finds-out-what-it-has-and-where.html |access-date=15 November 2012 |work=[[The New York Times]] |archive-date=17 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130617202410/http://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/01/arts/the-prado-finds-out-what-it-has-and-where.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

The main building was enlarged with short pavilions in the rear between 1900 and 1960. The next enlargement was the incorporation of two buildings (nearby but not adjacent) into the institutional structure of the museum: the [[Casón del Buen Retiro]], which is equipped to display up to 400 paintings and which housed the bulk of the 20th-century art from 1971 to 1997, and the [[Salón de Reinos]] (Throne building), formerly the Army Museum. |

|||

[[File:Velázquez en El Prado.JPG|left|thumb|150px|A main promenade entrance is dominated by [[Statue of Velázquez (Madrid)|this 1899 bronze statue of Diego Velázquez]], by Aniceto Marinas]] |

|||

The main building was enlarged with short pavilions in the rear between 1900 and 1960. The next enlargement was the incorporation of two buildings (nearby but not adjacent) into the institutional structure of the museum: the [[Casón del Buen Retiro]], which is equipped to display up to 400 paintings and which housed the bulk of the 20th-century art from 1971 to 1997, and the [[Salón de Reinos]] (Throne building), formerly the Army Museum. |

|||

In 1993, an extension proposed by the Prado's director at the time, Felipe Garin, was quickly abandoned after a wave of criticism.<ref name="expand">{{ |

In 1993, an extension proposed by the Prado's director at the time, Felipe Garin, was quickly abandoned after a wave of criticism.<ref name="expand">{{Cite news |last=Alan Riding |date=1 May 1995 |title=The Prado Embarks On Plans to Expand Into a Complex |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/01/arts/the-prado-embarks-on-plans-to-expand-into-a-complex.html |access-date=15 November 2012 |work=New York Times |archive-date=17 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130617205208/http://www.nytimes.com/1995/05/01/arts/the-prado-embarks-on-plans-to-expand-into-a-complex.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In the late 1990s, a $14 million roof work forced the Velázquez masterpiece ''Las Meninas'' to change galleries twice.<ref name="goodman">{{Cite news |last=Al Goodman |date=19 November 1998 |title=At Long Last, Expanding Spain's Treasure Chest |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/19/arts/arts-abroad-at-long-last-expanding-spain-s-treasure-chest.html |access-date=15 November 2012 |work=The New York Times}}</ref> In 1998, the Prado annex in the nearby Casón del Buen Retiro closed for a $10 million two-year overhaul that included three new underground levels. In 2007, the museum finally executed [[Rafael Moneo]]'s project to expand its exposition room to 16,000 square meters, hoping to increase the yearly number of visitors from 1.8 million to 2.5 million. |

||

[[File:Interior of Prado Museum Madrid.jpg| |

[[File:Interior of Prado Museum Madrid.jpg|thumb|The cafeteria in the underground extension by Rafael Moneo]] |

||

A glass-roofed and wedge-shaped foyer now contains the museum's shops and cafeteria, removing them from the main building to make more room for galleries.<ref name="goodman"/> The 16th-century Cloister of Jerónimo has been removed stone by stone to make foundations for increased stability of surrounding buildings and will be re-assembled in the new museum's extension. Hydraulic jacks had to be used to prevent the basement walls from falling during construction. |

A glass-roofed and wedge-shaped foyer now contains the museum's shops and cafeteria, removing them from the main building to make more room for galleries.<ref name="goodman" /> The 16th-century Cloister of Jerónimo has been removed stone by stone to make foundations for increased stability of surrounding buildings and will be re-assembled in the new museum's extension. Hydraulic jacks had to be used to prevent the basement walls from falling during construction. |

||

<ref>{{ |

<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chronology of the extension |url=http://www.museodelprado.es/en/la-institucion/the-extension/chronology-of-the-extension/ |access-date=15 November 2012 |publisher=Museo Nacional del Prado |archive-date=21 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130621025124/http://www.museodelprado.es/en/la-institucion/the-extension/chronology-of-the-extension/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> The enlargement is an underground building which connects the main building to another one entirely reconstructed. |

||

In November 2016, it was announced that British architect [[Norman Foster]], in a joint project with Carlos Rubio Carvajal, is to renovate the [[Salón de Reinos|Hall of Realms]], which once formed part of the Buen Retiro palace and transform it into a $32 million extension of the Prado. The museum announced the selection of Foster and Rubio after a jury reviewed the proposals of the eight competition finalists – including [[David Chipperfield]], [[Rem Koolhaas]] and [[Eduardo Souto de Moura]] – |

In November 2016, it was announced that British architect [[Norman Foster]], in a joint project with Carlos Rubio Carvajal, is to renovate the [[Salón de Reinos|Hall of Realms]], which once formed part of the Buen Retiro palace and transform it into a $32 million extension of the Prado. The museum announced the selection of Foster and Rubio after a jury reviewed the proposals of the eight competition finalists – including [[David Chipperfield]], [[Rem Koolhaas]] and [[Eduardo Souto de Moura]] –<ref>Hannah McGivern (25 November 2016), [http://theartnewspaper.com/news/norman-foster-to-design-prado-extension-in-historic-palace-/ Norman Foster to design Prado extension in historic palace] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161127024204/http://theartnewspaper.com/news/norman-foster-to-design-prado-extension-in-historic-palace-/ |date=27 November 2016 }} ''[[The Art Newspaper]]''.</ref> who had already been shortlisted from an initial list of 47 international teams of architects.<ref name="nytimes.com">Raphael Minder (25 November 2016), [https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/25/arts/design/norman-foster-to-remodel-palace-for-prado-extension.html Norman Foster to Remodel Palace for Prado Extension] ''[[New York Times]]''.</ref> The building was acquired by the Prado in 2015, after having served as an army museum until 2005. The project is designed to give the Prado about 61,500 square feet of additional available space, of which about 27,000 square feet will be used to exhibit works.<ref name="nytimes.com" /> Only in 2021, the Spanish government approved the plans and awarded the project 36 million euros.<ref>Gareth Harris (30 September 2021), [https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/09/30/prado-extension-designed-by-norman-foster-finally-gets-the-green-light Prado extension designed by Norman Foster finally gets the green light] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210930202609/https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/09/30/prado-extension-designed-by-norman-foster-finally-gets-the-green-light |date=30 September 2021 }} ''[[The Art Newspaper]]''.</ref> |

||

==Historic structure== |

==Historic structure== |

||

{{multiple image |

|||

[[File:Museo del Prado (Madrid) 19.jpg|thumb|The Goya Gate in the north façade of the museum.]] |

|||

| direction = vertical |

|||

| width = 220 |

|||

| header = |

|||

| image1 = Museo del Prado (Madrid) 19.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = |

|||

| caption1 = North façade (Goya entrance) |

|||

| image2 = Madrid-Prado Museum-Murillo.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

| caption2 = South façade (Murillo entrance) |

|||

}} |

|||

The |

The Prado Museum building is one of the buildings constructed during the reign of [[Charles III of Spain|Charles III]] (Carlos III) as part of a grandiose building scheme designed to bestow upon [[Madrid]] a monumental urban space. The building was initially conceived by [[José Moñino y Redondo, conde de Floridablanca|José Moñino y Redondo, count of Floridablanca]], and was commissioned in 1785 by Charles III for the ''reurbanización'' of the Paseo del Prado. To this end, Charles III called on one of his favorite architects, [[Juan de Villanueva]], author also of the nearby Botanical Garden and the City Hall of Madrid.<ref name="chronology">{{Cite web |title=Chronology of Museo del Prado, 1785 |url=http://www.museodelprado.es/index.php?id=904 |access-date=15 November 2012 |publisher=Museo Nacional del Prado |language=es |archive-date=15 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121015133249/http://www.museodelprado.es/index.php?id=904 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

The ''prado'' ("meadow") that was where the museum now stands gave its name to the area, the Salón del Prado (later [[Paseo del Prado]]), and to the museum itself upon [[nationalisation]]. Work on the building stopped at the conclusion of Charles III's reign and throughout the [[Peninsular War]] and was only initiated again during the reign of Charles III's grandson, [[Ferdinand VII of Spain|Ferdinand VII]]. The premises had been used as headquarters for the [[cavalry]] and a [[gunpowder]]-store for the [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon]]ic troops based in Madrid during the war. |

The ''prado'' ("meadow") that was where the museum now stands gave its name to the area, the Salón del Prado (later [[Paseo del Prado]]), and to the museum itself upon [[nationalisation]]. Work on the building stopped at the conclusion of Charles III's reign and throughout the [[Peninsular War]] and was only initiated again during the reign of Charles III's grandson, [[Ferdinand VII of Spain|Ferdinand VII]]. The premises had been used as headquarters for the [[cavalry]] and a [[gunpowder]]-store for the [[Napoleon I of France|Napoleon]]ic troops based in Madrid during the war. |

||

The next renovations that this |

The next renovations that this museum will undergo will be conducted by British architect Norman Foster. This renovation was approved in June 2020 and is expected to take a minimum of four years.<ref>{{Cite web |date=25 June 2019 |title=Así es la ampliación del Museo del Prado de Norman Foster |url=https://www.abc.es/cultura/abci-ampliacion-museo-prado-norman-foster-201906251802_noticia.html?ref=https:%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F |access-date=13 November 2020 |website=ABC}}</ref> |

||

==Special exhibitions== |

|||

Between 8 November 2011 and 25 March 2012, a group of 179 works of art were brought to the Museo del Prado from the [[Hermitage Museum]] in [[St. Petersburg]].<ref name="hermitage">{{cite web| url=http://www.museodelprado.es/en/exhibitions/exhibitions/at-the-museum/tesoros-del-hermitage/| title=The Hermitage in the Prado| publisher=Museo Nacional del Prado| access-date=15 November 2012}}</ref> Notable works included: |

|||

* ''[[:File:Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn - A Scholar.JPG|A Scholar]]'' (1631), by [[Rembrandt]] |

|||

* ''[[The Lute Player (Caravaggio)|The Lute Player]]'' (c. 1596), by [[Caravaggio]] |

|||

* ''[[Ecstasy of Saint Teresa]]'' (1647), by [[Gian Lorenzo Bernini|Bernini]] |

|||

* ''[[Game of Bowls]]'' (1908), by [[Henri Matisse]] |

|||

* ''Bouquet of Cornflowers with Stems of Oats in a Vase'' (c. 1900), by [[House of Fabergé]] |

|||

* ''[[List of works by Claude Monet|Pond at Montgeron]]'' (1876), by [[Claude Monet]] |

|||

* ''Belt buckle with a monster attacking a horse'', (4th–3rd century BC), (gold ornament from Peter I's [[Siberia]]n Collection) |

|||

* ''Moonrise, Two Men on the Shore'' (c. 1900), by [[Caspar David Friedrich]] |

|||

* [[:File:Kandinsky - Composition VI (1913).jpg|Composition VI]] (1913), by [[Wassily Kandinsky]] |

|||

* ''Metaphysical Still life'' (1918), by [[Giorgio Morandi]] |

|||

Conversely, for the first time in its 200-year history, the Museo del Prado has toured an exhibition of its renowned collection of Italian masterpieces at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, from 16 May 2014 until 31 August 2014. Many of the works have never before left Spain. |

|||

==Nearby museums== |

|||

A few meters away we can find two museums of important international relevance, such as [[Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum]] and the [[Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía|Museo Reina Sofía]]. |

|||

Nearby is the [[Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando]]. The [[National Archaeological Museum of Spain|Museo Arqueológico]] houses some art of [[Ancient Egypt]], [[Mesopotamia]], [[Ancient Greece|Greece]], and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]] formerly in the collection of the Prado. |

|||

The [[Museo Naval de Madrid|Naval Museum]], managed by the [[Ministry of Defence (Spain)|Ministry of Defence]], is also nearby. |

|||

==Management== |

|||

===Funding=== |

|||

Until the early 2000s, the Prado's annual income was approximately $18 million, $15 million of which came from the government and the remainder from private contributions, publications, and admissions.<ref name="kimmelman">{{cite news| author=Michael Kimmelman| date=21 November 1993| url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/21/arts/art-view-new-brooms-sweep-madrid-s-museums.html| title=New Brooms Sweep Madrid's Museums| work=The New York Times| access-date=15 November 2012| author-link=Michael Kimmelman}}</ref> In 2001, the conservative government of [[José María Aznar]] decided to change the museum's financing platform, ushering in a public-private partnership. Under its new bylaws, which the [[Cortes Generales]] approved in 2003, the Prado must gradually reduce its level of state support to 50 percent from 80 percent. In exchange, the museum gained control of the budget — now roughly €35 million — and the power to raise money from corporate donations and merchandising. However, its recent €150 million expansion was paid for by the Spanish state.<ref name="fuchs">{{cite news| author=Dale Fuchs| date=24 December 2004| url=https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/24/business/worldbusiness/24iht-wbspot24_ed3_.html| title=The art of financing the Prado| work=New York Times| access-date=15 November 2012}}</ref> |

|||

In 1991, [[Manuel Villaescusa]] bequeathed his fortune of nearly $40 million in Madrid real estate to the Prado, to be used solely for the acquisition of paintings. The museum subsequently sold Villaescusa's buildings to realize income from them. The bequest suddenly made the Prado one of the most formidable bidders for paintings in the world.<ref name="kimmelman"/> |

|||

===Directors=== |

|||

The first four directors were drawn from nobility. From 1838 to 1960, the directors were mostly artists. Since then, most of them have been [[art history|art historians]]. |

|||

{{div col}} |

|||

*[[José Gabriel de Silva-Bazán, 10th Marquess of Santa Cruz|The Marquess of Santa Cruz]], 1817–1820 |

|||

*[[Pedro de Alcántara Téllez-Girón, 2nd Prince of Anglona|The Prince of Anglona]], 1820–1823 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|José Idiáquez Carvajal|es}}, 1823–1826 |

|||

*[[José Rafael de Silva Fernández de Híjar, 12th Duke of Híjar|The Duke of Híjar]], 1826–1838 |

|||

*[[José de Madrazo]], 1838–1857 |

|||

*[[Juan Antonio de Ribera]], 1857–1860 |

|||

*[[Federico de Madrazo]], 1860–1868 |

|||

*[[Antonio Gisbert]], 1868–1873 |

|||

*[[Francisco Sans Cabot]], 1873–1881 |

|||

*[[Federico de Madrazo]], 1881–1894 |

|||

*[[Vicente Palmaroli]], 1894–1896 |

|||

*[[Francisco Pradilla]], 1896–1898 |

|||

*[[Luis Álvarez Catalá]], 1898–1901 |

|||

*[[José Villegas Cordero]], 1901–1918 |

|||

*[[Aureliano de Beruete y Moret]], 1918–1922 |

|||

*[[Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor]], 1922–1931 |

|||

*[[Ramón Pérez de Ayala]], 1931–1936 |

|||

*[[Pablo Ruiz Picasso]], 1936–1939 |

|||

*[[Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor]], 1939–1960 |

|||

*[[Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón]], 1960–1968 |

|||

*[[Diego Angulo Íñiguez]], 1968–1971 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Xavier de Salas Bosch|es}}, 1971–1978 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|José Manuel Pita Andrade|es}}, 1978–1981 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Federico Sopeña|es}}, 1981–1983 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Alfonso Pérez Sánchez|es}}, 1983–1991 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Felipe Garín Llombart|es}}, 1991–1993 |

|||

*[[Francisco Calvo Serraller]], 1993–1994 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|José María Luzón Nogué|es}}, 1994–1996 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Fernando Checa Cremades|es}}, 1996–2002 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Miguel Zugaza Miranda|es}}, 2002–2017 |

|||

*{{Interlanguage link multi|Miguel Falomir|es}}, 2017 – present |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

== Collection highlights == |

== Collection highlights == |

||

{{main|Spanish royal collection}} |

|||

{{Details|:Category:Collections of the Museo del Prado}} |

|||

{{Details|:Category:Collection of the Museo del Prado}} |

|||

{{see also|British paintings in the Museo del Prado}} |

{{see also|British paintings in the Museo del Prado}} |

||

[[File:El jardín de las Delicias, de El Bosco.jpg|thumb|260px|[[Hieronymus Bosch]], ''[[The Garden of Earthly Delights]]'', between 1480 and 1505 |

[[File:El jardín de las Delicias, de El Bosco.jpg|thumb|260px|[[Hieronymus Bosch]], ''[[The Garden of Earthly Delights]]'', between 1480 and 1505]] |

||

[[File:Las Meninas, by Diego Velázquez, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|thumb|260px|[[Diego Velázquez]], ''[[Las Meninas]]'', between 1656 and 1657 |

[[File:Las Meninas, by Diego Velázquez, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|thumb|260px|[[Diego Velázquez]], ''[[Las Meninas]]'', between 1656 and 1657]] |

||

[[File:Velázquez - El Triunfo de Baco o Los Borrachos (Museo del Prado, 1628-29).jpg|thumb|260px|[[Diego Velázquez]], ''[[The Triumph of Bacchus]]'', 1628–29]] |

[[File:Velázquez - El Triunfo de Baco o Los Borrachos (Museo del Prado, 1628-29).jpg|thumb|260px|[[Diego Velázquez]], ''[[The Triumph of Bacchus]]'', 1628–29]] |

||

[[File:La Anunciación, de Fra Angelico.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Fra Angelico]], ''Annunciation'', 1430–32]] |

|||

[[File:Raphael Spasimo.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Raphael]], ''[[Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary]]'', 1517]] |

|||

[[File:The Triumph of Death P001393.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Pieter Bruegel the Elder]], ''[[The Triumph of Death]],'' c. 1562]] |

|||

[[File:La adoración de los Reyes Magos (Rubens, Prado).jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Adoration of the Magi]]'', 1609/1628-1629]] |

|||

[[File:The Three Graces, by Peter Paul Rubens, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Three Graces,]]'' c.1635]] |

|||

===Selected works=== |

===Selected works=== |

||

<gallery widths=" |

<gallery widths="160" heights="160" perrow="5"> |

||

File:Weyden-descendimiento-prado-Ca-1435.jpg|[[Rogier van der Weyden]], ''[[The Descent from the Cross (van der Weyden)|The Descent from the Cross]]'', c. 1435 |

File:Weyden-descendimiento-prado-Ca-1435.jpg|[[Rogier van der Weyden]], ''[[The Descent from the Cross (van der Weyden)|The Descent from the Cross]]'', c. 1435 |

||

File:Andrea Mantegna 047.jpg|[[Andrea Mantegna]], ''[[Death of the Virgin (Mantegna)|Death of the Virgin]]'', c. 1461 |

File:Andrea Mantegna 047.jpg|[[Andrea Mantegna]], ''[[Death of the Virgin (Mantegna)|Death of the Virgin]]'', c. 1461 |

||

| Line 188: | Line 119: | ||

File:Albrecht Dürer - Self-Portrait at 26 - WGA6925.jpg|[[Albrecht Dürer]] ''[[Self-Portrait (Dürer, Madrid)|Self-portrait]]'', 1498 |

File:Albrecht Dürer - Self-Portrait at 26 - WGA6925.jpg|[[Albrecht Dürer]] ''[[Self-Portrait (Dürer, Madrid)|Self-portrait]]'', 1498 |

||

File:Albrecht Dürer - Adam and Eve (Prado) 2.jpg|[[Albrecht Dürer]] ''[[Adam and Eve (Dürer)|Adam and Eve]]'', 1507 |

File:Albrecht Dürer - Adam and Eve (Prado) 2.jpg|[[Albrecht Dürer]] ''[[Adam and Eve (Dürer)|Adam and Eve]]'', 1507 |

||

File:Fernando yañez-santa catalina-prado.jpg|[[Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina]], ''Saint Catherine of Alexandria'', c. 1510 |

|||

File:Portrait of a Cardinal, by Raffael, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Raphael]], ''[[Portrait of a Cardinal (Raphael)|Portrait of a Cardinal]]'', c. 1510–11 |

File:Portrait of a Cardinal, by Raffael, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Raphael]], ''[[Portrait of a Cardinal (Raphael)|Portrait of a Cardinal]]'', c. 1510–11 |

||

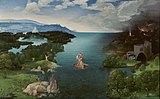

File:Crossing the River Styx.jpg|[[Joachim Patinir]], ''[[ |

File:Crossing the River Styx.jpg|[[Joachim Patinir]], ''[[Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx]]'', c. 1515–1524 |

||

File:El Lavatorio (Tintoretto).jpg|[[Tintoretto]], ''[[Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet (Tintoretto)|Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet]]'', c. 1518 |

File:El Lavatorio (Tintoretto).jpg|[[Tintoretto]], ''[[Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet (Tintoretto)|Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet]]'', c. 1518 |

||

File:Rafael - La Perla.JPG|[[Raphael]], ''[[La Perla (painting)|The Pearl]]'', c. |

File:Rafael - La Perla.JPG|[[Raphael]], ''[[La Perla (painting)|The Pearl]]'', c. 1518–1520 |

||

File:Correggio Noli Me Tangere.jpg|[[Correggio]], ''[[Noli me tangere (Correggio)|Noli me tangere]]'', c. 1525 |

File:Correggio Noli Me Tangere.jpg|[[Correggio]], ''[[Noli me tangere (Correggio)|Noli me tangere]]'', c. 1525 |

||

File:Bacanal de los andrios.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[The Bacchanal of the Andrians|Bacchanal of the Andrians]]'', c. 1523–1526 |

File:Bacanal de los andrios.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[The Bacchanal of the Andrians|Bacchanal of the Andrians]]'', c. 1523–1526 |

||

File:Carlos V en Mühlberg, by Titian, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[Equestrian Portrait of Charles V]]'', c. 1548 |

File:Carlos V en Mühlberg, by Titian, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[Equestrian Portrait of Charles V]]'', c. 1548 |

||

File:La Gloria (Tiziano).jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[La Gloria (Titian)]]'', c. 1554 |

|||

File:Tizian 091.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[The Fall of Man (Titian)|The Fall of Man]]'', c. 1570 |

File:Tizian 091.jpg|[[Titian]], ''[[The Fall of Man (Titian)|The Fall of Man]]'', c. 1570 |

||

File:Trinidad El Greco2.jpg|[[El Greco]], '' |

File:Trinidad El Greco2.jpg|[[El Greco]], ''[[Holy Trinity (El Greco)]]'', 1577–1579 |

||

File:El caballero de la mano en el pecho, by El Greco, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[El Greco]], ''[[The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest|The Knight with His Hand on His Breast]]'', c. 1580 |

File:El caballero de la mano en el pecho, by El Greco, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[El Greco]], ''[[The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest|The Knight with His Hand on His Breast]]'', c. 1580 |

||

File:Venus y Adonis (Veronese).jpg|[[Paolo Veronese]], ''[[Venus and Adonis (Veronese, Madrid)|Venus and Adonis]]'', c. 1580 |

File:Venus y Adonis (Veronese).jpg|[[Paolo Veronese]], ''[[Venus and Adonis (Veronese, Madrid)|Venus and Adonis]]'', c. 1580 |

||

File:David and Goliath by Caravaggio.jpg|[[Caravaggio]], ''[[David and Goliath (Caravaggio)|David and Goliath]]'', 1600 |

File:David and Goliath by Caravaggio.jpg|[[Caravaggio]], ''[[David and Goliath (Caravaggio)|David and Goliath]]'', 1600 |

||

File:Ciego tocando la zanfonía (Georges de La Tour).jpg| |

File:Ciego tocando la zanfonía (Georges de La Tour).jpg|[[Georges de La Tour]], ''Ciego tocando la zanfonía'', 1610–1630 |

||

File:Hipómenes y Atalanta (Reni).jpg| |

File:Hipómenes y Atalanta (Reni).jpg|[[Guido Reni]], ''[[Atalanta and Hippomenes|Hipómenes y Atalanta]]'', 1618–19 |

||

File:La adoración de los pastores (El Greco).jpg|[[El Greco]], ''[[The Adoration of the Shepherds (El Greco, Madrid)]]'', 1577–1579 |

|||

File:Landscape with Sea and Mountains (1).jpg|[[Joos de Momper]], ''[[Landscape with Sea and Mountains]]'', c. 1623 |

File:Landscape with Sea and Mountains (1).jpg|[[Joos de Momper]], ''[[Landscape with Sea and Mountains]]'', c. 1623 |

||

Gaspar de Crayer - Caritas Romana (Prado).jpg| |

File:Gaspar de Crayer - Caritas Romana (Prado).jpg|[[Gaspar de Crayer]], ''[[Caritas Romana (de Crayer)|Caritas Romana]]'', c. 1625 |

||

File:El Parnaso (Poussin).jpg|[[Nicolas Poussin]], ''[[Parnassus (Poussin)|Parnassus]]'', c. 1630–31 |

File:El Parnaso (Poussin).jpg|[[Nicolas Poussin]], ''[[Parnassus (Poussin)|Parnassus]]'', c. 1630–31 |

||

File:Artemisia, by Rembrandt, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Rembrandt]], ''[[Judith at the Banquet of Holofernes|Artemisia]]'', c. 1634 |

File:Artemisia, by Rembrandt, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Rembrandt]], ''[[Judith at the Banquet of Holofernes|Artemisia]]'', c. 1634 |

||

| Line 211: | Line 145: | ||

File:El sueño de Jacob, por José de Ribera.jpg|[[José de Ribera]], ''[[Jacob's Dream]]'', 1639 |

File:El sueño de Jacob, por José de Ribera.jpg|[[José de Ribera]], ''[[Jacob's Dream]]'', 1639 |

||

File:Peter Paul Rubens 115.jpg|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Judgment of Paris (Rubens)|The Judgement of Paris]]'', 1638–39 |

File:Peter Paul Rubens 115.jpg|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Judgment of Paris (Rubens)|The Judgement of Paris]]'', 1638–39 |

||

File:Paisaje con el embarco en Ostia de Santa Paula Romana (Gellée).jpg| |

File:Paisaje con el embarco en Ostia de Santa Paula Romana (Gellée).jpg|[[Claude Lorrain]] ''[[Landscape with St Paula of Rome Embarking at Ostia|El embarque de santa Paula]]'', 1639–40 |

||

File:Francisco de Zurbarán 006.jpg|[[Francisco de Zurbarán]], ''[[Agnus Dei, (Zurbarán)|Agnus Dei]]'', 1635–1640 |

File:Francisco de Zurbarán 006.jpg|[[Francisco de Zurbarán]], ''[[Agnus Dei, (Zurbarán)|Agnus Dei]]'', 1635–1640 |

||

File:Bodegón de recipientes (Zurbarán).jpg|[[Francisco de Zurbarán]], ''[[Still Life with Pots]]'', c. 1650 |

|||

File:Murillo immaculate conception.jpg|[[Bartolomé Esteban Murillo]], ''[[The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables|La Inmaculada de Soult]]'', 1678 |

File:Murillo immaculate conception.jpg|[[Bartolomé Esteban Murillo]], ''[[The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables|La Inmaculada de Soult]]'', 1678 |

||

File:The Immaculate Conception, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Giovanni Battista Tiepolo]], ''The Immaculate Conception'', 1767 |

File:The Immaculate Conception, by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|[[Giovanni Battista Tiepolo]], ''The Immaculate Conception'', 1767 |

||

File:El Tres de Mayo, by Francisco de Goya, from Prado thin black margin.jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[The Third of May 1808]] |

File:El Tres de Mayo, by Francisco de Goya, from Prado thin black margin.jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[The Third of May 1808]]'', 1814 |

||

File:Goya Dog.jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[The Dog (Goya)|The Dog]] |

File:Goya Dog.jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[The Dog (Goya)|The Dog]]'', 1819–1823 |

||

File:Francisco de Goya, Saturno devorando a su hijo (1819-1823).jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[Saturn Devouring His Son]]'', 1819–1823 |

File:Francisco de Goya, Saturno devorando a su hijo (1819-1823).jpg|[[Francisco Goya]], ''[[Saturn Devouring His Son]]'', 1819–1823 |

||

File:Paul Baudry - The Pearl and the Wave - c 1862 - Detroit Institute of Arts.jpg|[[Paul Baudry]], [[The Pearl and the Wave]], 1862 |

File:Paul Baudry - The Pearl and the Wave - c 1862 - Detroit Institute of Arts.jpg|[[Paul Baudry]], ''[[The Pearl and the Wave]]'', 1862 |

||

File:Fusilamiento de Torrijos (Gisbert).jpg|[[Antonio Gisbert Pérez]], ''[[Execution of Torrijos and his Companions on the Beach at Málaga]]'', 1882 |

File:Fusilamiento de Torrijos (Gisbert).jpg|[[Antonio Gisbert Pérez]], ''[[Execution of Torrijos and his Companions on the Beach at Málaga]]'', 1882 |

||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

==Management== |

|||

[[File:La Anunciación, de Fra Angelico.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Fra Angelico]], ''Annunciation'', 1430–32]] |

|||

[[File:Raphael Spasimo.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Raphael]], ''[[Christ Falling on the Way to Calvary]]'', 1517]] |

|||

[[File:The Triumph of Death P001393.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Pieter Bruegel the Elder]], ''[[The Triumph of Death]]'', c. 1562]] |

|||

[[File:La adoración de los Reyes Magos (Rubens, Prado).jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Adoration of the Magi]]'', 1609/1628–1629]] |

|||

[[File:The Three Graces, by Peter Paul Rubens, from Prado in Google Earth.jpg|thumbnail|260px|[[Peter Paul Rubens]], ''[[The Three Graces (Rubens, Madrid)|The Three Graces]]'', c. 1635]] |

|||

===Funding=== |

|||

In 1991, [[Manuel Villaescusa]] bequeathed his fortune of nearly $40 million in Madrid real estate to the Prado, to be used solely for the acquisition of paintings. The museum subsequently sold Villaescusa's buildings to realize income from them. The bequest suddenly made the Prado one of the most formidable bidders for paintings in the world.<ref name="kimmelman" /> |

|||

Until the early 2000s, the Prado's annual income was approximately $18 million, $15 million of which came from the government and the remainder from private contributions, publications, and admissions.<ref name="kimmelman">{{Cite news |last=Michael Kimmelman |author-link=Michael Kimmelman |date=21 November 1993 |title=New Brooms Sweep Madrid's Museums |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/21/arts/art-view-new-brooms-sweep-madrid-s-museums.html |access-date=15 November 2012 |work=The New York Times |archive-date=17 June 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130617191056/http://www.nytimes.com/1993/11/21/arts/art-view-new-brooms-sweep-madrid-s-museums.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2001, the conservative government of [[José María Aznar]] decided to change the museum's financing platform, ushering in a public-private partnership. Under its new bylaws, which the [[Cortes Generales]] approved in 2003, the Prado must gradually reduce its level of state support to 50 percent from 80 percent. In exchange, the museum gained control of the budget — which was roughly €35 million in 2004 — and the power to raise money from corporate donations and merchandising.<ref name="fuchs" /> However, its 2004 €150 million expansion was paid for by the Spanish state.<ref name="fuchs">{{Cite news |last=Dale Fuchs |date=24 December 2004 |title=The art of financing the Prado |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/24/business/worldbusiness/24iht-wbspot24_ed3_.html |access-date=15 November 2012 |work=New York Times}}</ref> |

|||

===Directors=== |

|||

The first four directors were drawn from nobility. From 1838 to 1960, the directors were mostly artists. Since then, most of them have been [[art history|art historians]]. |

|||

{{div col}} |

|||

* [[José Gabriel de Silva-Bazán, 10th Marquess of Santa Cruz|The Marquess of Santa Cruz]], 1817–1820 |

|||

* [[Pedro de Alcántara Téllez-Girón, 2nd Prince of Anglona|The Prince of Anglona]], 1820–1823 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|José Idiáquez Carvajal|es}}, 1823–1826 |

|||

* [[José Rafael de Silva Fernández de Híjar, 12th Duke of Híjar|The Duke of Híjar]], 1826–1838 |

|||

* [[José de Madrazo]], 1838–1857 |

|||

* [[Juan Antonio de Ribera]], 1857–1860 |

|||

* [[Federico de Madrazo]], 1860–1868 |

|||

* [[Antonio Gisbert]], 1868–1873 |

|||

* [[Francisco Sans Cabot]], 1873–1881 |

|||

* [[Federico de Madrazo]], 1881–1894 |

|||

* [[Vicente Palmaroli]], 1894–1896 |

|||

* [[Francisco Pradilla]], 1896–1898 |

|||

* [[Luis Álvarez Catalá]], 1898–1901 |

|||

* [[José Villegas Cordero]], 1901–1918 |

|||

* [[Aureliano de Beruete y Moret]], 1918–1922 |

|||

* [[Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor]], 1922–1931 |

|||

* [[Ramón Pérez de Ayala]], 1931–1936 |

|||

* [[Pablo Ruiz Picasso]], 1936–1939 |

|||

* [[Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor]], 1939–1960 |

|||

* [[Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón]], 1960–1968 |

|||

* [[Diego Angulo Íñiguez]], 1968–1971 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Xavier de Salas Bosch|es}}, 1971–1978 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|José Manuel Pita Andrade|es}}, 1978–1981 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Federico Sopeña|es}}, 1981–1983 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Alfonso Pérez Sánchez|es}}, 1983–1991 |

|||

* [[Felipe Garín Llombart]], 1991–1993 |

|||

* [[Francisco Calvo Serraller]], 1993–1994 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|José María Luzón Nogué|es}}, 1994–1996 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Fernando Checa Cremades|es}}, 1996–2002 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Miguel Zugaza Miranda|es}}, 2002–2017 |

|||

* {{Interlanguage link multi|Miguel Falomir|es}}, 2017 – present |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

==In Google Earth== |

==In Google Earth== |

||

In 2009, the Prado Museum selected 14 of its most important paintings to be displayed in [[Google Earth]] and [[Google Maps]] at extremely high resolution, with the largest displayed at 14,000 [[megapixel]]s. The images' zoom capability allows for close-up views of paint texture and fine detail.<ref>{{ |

In 2009, the Prado Museum selected 14 of its most important paintings to be displayed in [[Google Earth]] and [[Google Maps]] at extremely high resolution, with the largest displayed at 14,000 [[megapixel]]s. The images' zoom capability allows for close-up views of paint texture and fine detail.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Tremlett |first=Giles |author-link=Giles Tremlett |date=14 January 2009 |title=Online gallery zooms in on Prado's masterpieces (even the smutty bits) |url=https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/14/museums-internet-google-earth-prado |access-date=5 March 2019 |work=[[The Guardian]] |publisher=[[Guardian News & Media Limited]] |location=London |archive-date=2 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202105601/https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/14/museums-internet-google-earth-prado |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The Prado in Google Earth |url=https://www.google.com/intl/en/landing/prado/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090117180611/http://www.google.com/intl/en/landing/prado/ |archive-date=17 January 2009 |access-date=24 January 2009 |website=[[Google.com]]}}</ref> |

||

==Nearby museums== |

|||

A few meters away there are two museums of international significance, the [[Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum]] and the [[Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía|Museo Reina Sofía]]. |

|||

Nearby is the [[Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando]]. The [[National Archaeological Museum of Spain|Museo Arqueológico]] houses the archaeological collections formerly in the collection of the Prado, with works from Spain, [[Ancient Egypt]], [[Mesopotamia]], [[Ancient Greece|Greece]], and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]]. |

|||

The [[Museo Naval de Madrid|Naval museum]], managed by the [[Ministry of Defence (Spain)|Ministry of Defence]], is also nearby. |

|||

==Special exhibitions== |

|||

Between 8 November 2011 and 25 March 2012, a group of 179 works of art were brought to the Museo del Prado from the [[Hermitage Museum]] in [[St. Petersburg]].<ref name="hermitage">{{Cite web |title=The Hermitage in the Prado |url=http://www.museodelprado.es/en/exhibitions/exhibitions/at-the-museum/tesoros-del-hermitage/ |access-date=15 November 2012 |publisher=Museo Nacional del Prado |archive-date=20 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130820223941/http://www.museodelprado.es/en/exhibitions/exhibitions/at-the-museum/tesoros-del-hermitage/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> Notable works included: |

|||

* ''[[:File:Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn - A Scholar.JPG|A Scholar]]'' (1631), by [[Rembrandt]] |

|||

* ''[[The Lute Player (Caravaggio)|The Lute Player]]'' (c. 1596), by [[Caravaggio]] |

|||

* ''[[Ecstasy of Saint Teresa]]'' (1647), by [[Gian Lorenzo Bernini|Bernini]] |

|||

* ''[[Game of Bowls]]'' (1908), by [[Henri Matisse]] |

|||

* ''Bouquet of Cornflowers with Stems of Oats in a Vase'' (c. 1900), by [[House of Fabergé]] |

|||

* ''[[List of works by Claude Monet|Pond at Montgeron]]'' (1876), by [[Claude Monet]] |

|||

* ''Belt buckle with a monster attacking a horse'', (4th–3rd century BC), (gold ornament from Peter I's [[Siberia]]n Collection) |

|||

* ''Moonrise, Two Men on the Shore'' (c. 1900), by [[Caspar David Friedrich]] |

|||

* [[:File:Kandinsky - Composition VI (1913).jpg|Composition VI]] (1913), by [[Wassily Kandinsky]] |

|||

* ''Metaphysical Still life'' (1918), by [[Giorgio Morandi]] |

|||

Conversely, for the first time in its 200-year history, the Museo del Prado has toured an exhibition of its renowned collection of Italian masterpieces at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, from 16 May 2014 until 31 August 2014. Many of the works have never before left Spain.{{citation needed|date=April 2024}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[List of largest art museums]] |

|||

* [[Josefa Bayeu (painting)]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 229: | Line 237: | ||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

*Alcolea Blanch, Santiago. ''The Prado'', translated by Richard-Lewis Rees and Angela Patricia Hall. |

* Alcolea Blanch, Santiago. ''The Prado'', translated from the Spanish by Richard-Lewis Rees and Angela Patricia Hall. New York: Abrams 1991. {{ISBN|0-8109-8147-5}} |

||

*Araujo Sánchez, Ceferino. ''Los museos de España''. Madrid 1875. |

* Araujo Sánchez, Ceferino. ''Los museos de España''. Madrid 1875. |

||

*Blanco, Antonio. ''Museo del Prado. Catálago de la Escultura. I Esculturas clásicas. II. Escultura, copia e imitaciones de las antiguas) (siglos XVI–XVIII)''. Madrid 1957. |

* Blanco, Antonio. ''Museo del Prado. Catálago de la Escultura. I Esculturas clásicas. II. Escultura, copia e imitaciones de las antiguas) (siglos XVI–XVIII)''. Madrid 1957. |

||

*Luca de Tena, Consuelo and Mena, Manuela. ''Guía actualizada del Prado''. Madrid: Alfiz 1985. |

* Luca de Tena, Consuelo and Mena, Manuela. ''Guía actualizada del Prado''. Madrid: Alfiz 1985. |

||

*Rumeu de Armas, Antonio. ''Origen y fundación del Museo del Prado''. Madrid: Instituto de España 1980. |

* Rumeu de Armas, Antonio. ''Origen y fundación del Museo del Prado''. Madrid: Instituto de España 1980. |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons and category|Museo del Prado}} |

{{Commons and category|Museo del Prado}} |

||

*{{Official website}} |

* {{Official website}} |

||

*[https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion Masterworks in the collection] |

* [https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion Masterworks in the collection] |

||

*[https://www.google.com/intl/en/landing/prado/ Prado in Google Earth |

* [https://www.google.com/intl/en/landing/prado/ Prado] in [[Google Earth]] (extra high resolution) |

||

{{Prado Museum}} |

{{Prado Museum}} |

||

| Line 247: | Line 255: | ||

{{Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities}} |

{{Princess of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

{{WikidataCoord}} |

|||

[[Category:Museo del Prado| ]] |

[[Category:Museo del Prado| ]] |

||

| Line 254: | Line 263: | ||

[[Category:Bien de Interés Cultural landmarks in Madrid]] |

[[Category:Bien de Interés Cultural landmarks in Madrid]] |

||

[[Category:Tourism in Madrid]] |

[[Category:Tourism in Madrid]] |

||

[[Category:Art museums established in 1819]] |

[[Category:Art museums and galleries established in 1819]] |

||

[[Category:1819 establishments in Spain]] |

[[Category:1819 establishments in Spain]] |

||

[[Category:Juan de Villanueva buildings]] |

[[Category:Juan de Villanueva buildings]] |

||

| Line 260: | Line 269: | ||

[[Category:Cultural tourism in Spain]] |

[[Category:Cultural tourism in Spain]] |

||

[[Category:Buildings and structures in Jerónimos neighborhood, Madrid]] |

[[Category:Buildings and structures in Jerónimos neighborhood, Madrid]] |

||

[[Category:Charles III of Spain]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 03:27, 16 December 2024

| |

Front façade (Velázquez entrance) in 2016 | |

| |

| Established | 19 November 1819 |

|---|---|

| Location | Paseo del Prado, Madrid, Spain |

| Type | Art museum, historic site |

| Visitors | 3,337,550 (2023)[1] Ranked 13th globally (2023)[2] |

| Director | Miguel Falomir[3] |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | museodelprado.es |

| Architect | Juan de Villanueva |

| Official name | Museo Nacional del Prado |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 1962 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0001374 |

The Museo del Prado (/ˈprɑːdoʊ/ PRAH-doh; Spanish pronunciation: [muˈseo ðel ˈpɾaðo]), officially known as Museo Nacional del Prado, is the main Spanish national art museum, located in central Madrid. It houses collections of European art, dating from the 12th century to the early 20th century, based on the former Spanish royal collection, and the single best collection of Spanish art. Founded as a museum of paintings and sculpture in 1819, it also contains important collections of other types of works. The numerous works by Francisco Goya, the single most extensively represented artist, as well as by Hieronymus Bosch, El Greco, Peter Paul Rubens, Titian, and Diego Velázquez, are some of the highlights of the collection. Velázquez and his keen eye and sensibility were also responsible for bringing much of the museum's fine collection of Italian masters to Spain, now one of the largest outside of Italy.

The collection currently comprises around 8,200 drawings, 7,600 paintings, 4,800 prints, and 1,000 sculptures, in addition to many other works of art and historic documents. As of 2012, the museum displayed about 1,300 works in the main buildings, while around 3,100 works were on temporary loan to various museums and official institutions. The remainder were in storage.[4]

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020 attendance plunged by 76 percent to 852,161. Nonetheless, the Prado was ranked as the 16th most-visited museum in the list of most-visited art museums in the world in 2020.[5] It is one of the largest museums in Spain.

The Prado and the nearby Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and the Museo Reina Sofía form Madrid's Golden Triangle of Art along the Paseo del Prado, which was included in the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2021.

History

[edit]The building that is now the home of the Museo Nacional del Prado was designed in 1785 by architect of the Enlightenment in Spain Juan de Villanueva on the orders of Charles III to house the Natural History Cabinet. Nonetheless, the building's final function was not decided until the monarch's grandson, Ferdinand VII, encouraged by his wife, Queen María Isabel de Braganza, decided to use it as a new Royal Museum of Paintings and Sculptures. The royal museum, which would soon become known as the National Museum of Painting and Sculpture, and subsequently the Museo Nacional del Prado, opened to the public for the first time in November 1819. It was created with the double aim of showing the works of art belonging to the Spanish Crown and to demonstrate to the rest of Europe that Spanish art was of equal merit to any other national school. Also, this museum needed several renovations during the 19th and 20th centuries, because of the increase of the collection as well as the increase of the public who wants to see all the collection that the museum hosted.[6]

The first catalogue of the museum, published in 1819 and solely devoted to Spanish painting, included 311 paintings, although at that time the museum housed 1,510 from the various royal residences, the Reales Sitios, including works from other schools. The exceptionally important royal collection, which forms the nucleus of the present-day Museo del Prado, started to increase significantly in the 16th century during the time of Charles V and continued under the succeeding Habsburg and Bourbon monarchs. Their efforts and determination led to the royal collection being enriched by some of the masterpieces now to be seen in the Prado. These include The Descent from the Cross (van der Weyden) by Rogier van der Weyden, The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch, The Nobleman with his Hand on his Chest by El Greco, Death of the Virgin (Mantegna) by Mantegna, The Holy Family, known as "La Perla (painting)", by Raphael, Equestrian Portrait of Charles V by Titian, Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet by Tintoretto, Dürer's Self-portrait at 26, Las Meninas by Velázquez, The Three Graces by Rubens, and The Family of Charles IV by Goya.[citation needed]

In addition to works from the Spanish royal collection, the other holdings increased and enriched the museum with further masterpieces, such as the two Majas by Goya. Among the now closed museums whose collections have been added to that of the Prado were the Museo de la Trinidad in 1872, and the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1971. In addition, numerous legacies, donations and purchases have been of crucial importance for the growth of the collection. Various works entered the Prado from the Museo de la Trinidad, including The Fountain of Grace by the School of Van Eyck, the Santo Domingo and San Pedro Martír altarpieces painted for the monastery of Santo Tomás in Ávila by Pedro Berruguete, and the five canvases by El Greco executed for the Colegio de doña María de Aragón. Most of the Museum's 19th-century paintings come from the former Museo de Arte Moderno, including works by the Madrazos, José de Madrazo y Agudo and Federico de Madrazo, Vicente López, Carlos de Haes, Eduardo Rosales and Sorolla.[citation needed]

Upon the deposition of Isabella II in 1868, the museum was nationalized and acquired the new name of "Museo del Prado". The building housed the royal collection of arts, and it rapidly proved too small. The first enlargement to the museum took place in 1918. Since the creation of the Museo del Prado more than 2,300 paintings have been incorporated into its collection, as well as numerous sculptures, prints, drawings and works of art through bequests, donations and purchases, which account for most of the New Acquisitions. Numerous bequests have enriched the museum's holdings, such as the outstanding collection of medals left to the museum by Pablo Bosch; the drawings and items of decorative art left by Pedro Fernández Durán as well as Van der Weyden's masterpiece, Duran Madonna; and the Ramón de Errazu bequest of 19th-century paintings. Particularly important donations include Barón Emile d'Erlanger's gift of Goya's Black Paintings in 1881. Among the numerous works that have entered the collection through purchase are some outstanding ones acquired in recent years including two works by El Greco, The Fable and The Flight into Egypt acquired in 1993 and 2001, Goya's The Countess of Chinchon bought in 2000, Velázquez's Portrait of Ferdinando Brandani, acquired in 2003, Bruegel's The Wine of Saint Martin's Day bought in 2010 and Fra Angelico's Madonna of the Pomegranate purchased in 2016.[citation needed]

Between 1873 and 1900, the Prado helped decorate city halls, new universities, and churches. During the Second Spanish Republic from 1931 to 1936, the focus was on developing provincial museums. During the Spanish Civil War, upon the recommendation of the League of Nations, the museum staff removed 353 paintings, 168 drawings and the Dauphin's Treasure and sent the art to Valencia, then later to Girona, and finally to Geneva. The art had to be returned across French territory in night trains to the museum upon the commencement of World War II. During the early years of the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, many paintings were sent to embassies.[7]

The main building was enlarged with short pavilions in the rear between 1900 and 1960. The next enlargement was the incorporation of two buildings (nearby but not adjacent) into the institutional structure of the museum: the Casón del Buen Retiro, which is equipped to display up to 400 paintings and which housed the bulk of the 20th-century art from 1971 to 1997, and the Salón de Reinos (Throne building), formerly the Army Museum.

In 1993, an extension proposed by the Prado's director at the time, Felipe Garin, was quickly abandoned after a wave of criticism.[8] In the late 1990s, a $14 million roof work forced the Velázquez masterpiece Las Meninas to change galleries twice.[9] In 1998, the Prado annex in the nearby Casón del Buen Retiro closed for a $10 million two-year overhaul that included three new underground levels. In 2007, the museum finally executed Rafael Moneo's project to expand its exposition room to 16,000 square meters, hoping to increase the yearly number of visitors from 1.8 million to 2.5 million.

A glass-roofed and wedge-shaped foyer now contains the museum's shops and cafeteria, removing them from the main building to make more room for galleries.[9] The 16th-century Cloister of Jerónimo has been removed stone by stone to make foundations for increased stability of surrounding buildings and will be re-assembled in the new museum's extension. Hydraulic jacks had to be used to prevent the basement walls from falling during construction. [10] The enlargement is an underground building which connects the main building to another one entirely reconstructed.

In November 2016, it was announced that British architect Norman Foster, in a joint project with Carlos Rubio Carvajal, is to renovate the Hall of Realms, which once formed part of the Buen Retiro palace and transform it into a $32 million extension of the Prado. The museum announced the selection of Foster and Rubio after a jury reviewed the proposals of the eight competition finalists – including David Chipperfield, Rem Koolhaas and Eduardo Souto de Moura –[11] who had already been shortlisted from an initial list of 47 international teams of architects.[12] The building was acquired by the Prado in 2015, after having served as an army museum until 2005. The project is designed to give the Prado about 61,500 square feet of additional available space, of which about 27,000 square feet will be used to exhibit works.[12] Only in 2021, the Spanish government approved the plans and awarded the project 36 million euros.[13]

Historic structure

[edit]The Prado Museum building is one of the buildings constructed during the reign of Charles III (Carlos III) as part of a grandiose building scheme designed to bestow upon Madrid a monumental urban space. The building was initially conceived by José Moñino y Redondo, count of Floridablanca, and was commissioned in 1785 by Charles III for the reurbanización of the Paseo del Prado. To this end, Charles III called on one of his favorite architects, Juan de Villanueva, author also of the nearby Botanical Garden and the City Hall of Madrid.[14]

The prado ("meadow") that was where the museum now stands gave its name to the area, the Salón del Prado (later Paseo del Prado), and to the museum itself upon nationalisation. Work on the building stopped at the conclusion of Charles III's reign and throughout the Peninsular War and was only initiated again during the reign of Charles III's grandson, Ferdinand VII. The premises had been used as headquarters for the cavalry and a gunpowder-store for the Napoleonic troops based in Madrid during the war.

The next renovations that this museum will undergo will be conducted by British architect Norman Foster. This renovation was approved in June 2020 and is expected to take a minimum of four years.[15]

Collection highlights

[edit]

Selected works

[edit]-

Andrea Mantegna, Death of the Virgin, c. 1461

-

Antonello da Messina, The Dead Christ Supported by an Angel, c. 1475

-

Albrecht Dürer Self-portrait, 1498

-

Albrecht Dürer Adam and Eve, 1507

-

Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1510

-

Raphael, Portrait of a Cardinal, c. 1510–11

-

Joachim Patinir, Landscape with Charon Crossing the Styx, c. 1515–1524

-

Tintoretto, Christ Washing the Disciples' Feet, c. 1518

-

Correggio, Noli me tangere, c. 1525

-

Titian, Bacchanal of the Andrians, c. 1523–1526

-

Titian, Equestrian Portrait of Charles V, c. 1548

-

Titian, La Gloria (Titian), c. 1554

-

Titian, The Fall of Man, c. 1570

-

El Greco, Holy Trinity (El Greco), 1577–1579

-

Paolo Veronese, Venus and Adonis, c. 1580

-

Caravaggio, David and Goliath, 1600

-

Georges de La Tour, Ciego tocando la zanfonía, 1610–1630

-

Guido Reni, Hipómenes y Atalanta, 1618–19

-

Gaspar de Crayer, Caritas Romana, c. 1625

-

Nicolas Poussin, Parnassus, c. 1630–31

-

Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda, 1634–35

-

Diego Velázquez, Mars Resting, 1639–1641

-

José de Ribera, Jacob's Dream, 1639

-

Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgement of Paris, 1638–39

-

Claude Lorrain El embarque de santa Paula, 1639–40

-

Francisco de Zurbarán, Agnus Dei, 1635–1640

-

Francisco de Zurbarán, Still Life with Pots, c. 1650

-

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The Immaculate Conception, 1767

-

Francisco Goya, The Dog, 1819–1823

-

Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823

Management

[edit]

Funding

[edit]In 1991, Manuel Villaescusa bequeathed his fortune of nearly $40 million in Madrid real estate to the Prado, to be used solely for the acquisition of paintings. The museum subsequently sold Villaescusa's buildings to realize income from them. The bequest suddenly made the Prado one of the most formidable bidders for paintings in the world.[16]

Until the early 2000s, the Prado's annual income was approximately $18 million, $15 million of which came from the government and the remainder from private contributions, publications, and admissions.[16] In 2001, the conservative government of José María Aznar decided to change the museum's financing platform, ushering in a public-private partnership. Under its new bylaws, which the Cortes Generales approved in 2003, the Prado must gradually reduce its level of state support to 50 percent from 80 percent. In exchange, the museum gained control of the budget — which was roughly €35 million in 2004 — and the power to raise money from corporate donations and merchandising.[17] However, its 2004 €150 million expansion was paid for by the Spanish state.[17]

Directors

[edit]The first four directors were drawn from nobility. From 1838 to 1960, the directors were mostly artists. Since then, most of them have been art historians.

- The Marquess of Santa Cruz, 1817–1820

- The Prince of Anglona, 1820–1823

- José Idiáquez Carvajal, 1823–1826

- The Duke of Híjar, 1826–1838

- José de Madrazo, 1838–1857

- Juan Antonio de Ribera, 1857–1860

- Federico de Madrazo, 1860–1868

- Antonio Gisbert, 1868–1873

- Francisco Sans Cabot, 1873–1881

- Federico de Madrazo, 1881–1894

- Vicente Palmaroli, 1894–1896

- Francisco Pradilla, 1896–1898

- Luis Álvarez Catalá, 1898–1901

- José Villegas Cordero, 1901–1918

- Aureliano de Beruete y Moret, 1918–1922

- Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, 1922–1931

- Ramón Pérez de Ayala, 1931–1936

- Pablo Ruiz Picasso, 1936–1939

- Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, 1939–1960

- Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón, 1960–1968

- Diego Angulo Íñiguez, 1968–1971

- Xavier de Salas Bosch, 1971–1978

- José Manuel Pita Andrade, 1978–1981

- Federico Sopeña, 1981–1983

- Alfonso Pérez Sánchez, 1983–1991

- Felipe Garín Llombart, 1991–1993

- Francisco Calvo Serraller, 1993–1994

- José María Luzón Nogué, 1994–1996

- Fernando Checa Cremades, 1996–2002

- Miguel Zugaza Miranda, 2002–2017

- Miguel Falomir, 2017 – present

In Google Earth

[edit]In 2009, the Prado Museum selected 14 of its most important paintings to be displayed in Google Earth and Google Maps at extremely high resolution, with the largest displayed at 14,000 megapixels. The images' zoom capability allows for close-up views of paint texture and fine detail.[18][19]

Nearby museums

[edit]A few meters away there are two museums of international significance, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum and the Museo Reina Sofía.

Nearby is the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. The Museo Arqueológico houses the archaeological collections formerly in the collection of the Prado, with works from Spain, Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and Rome.

The Naval museum, managed by the Ministry of Defence, is also nearby.

Special exhibitions

[edit]Between 8 November 2011 and 25 March 2012, a group of 179 works of art were brought to the Museo del Prado from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.[20] Notable works included:

- A Scholar (1631), by Rembrandt

- The Lute Player (c. 1596), by Caravaggio

- Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647), by Bernini

- Game of Bowls (1908), by Henri Matisse

- Bouquet of Cornflowers with Stems of Oats in a Vase (c. 1900), by House of Fabergé

- Pond at Montgeron (1876), by Claude Monet

- Belt buckle with a monster attacking a horse, (4th–3rd century BC), (gold ornament from Peter I's Siberian Collection)

- Moonrise, Two Men on the Shore (c. 1900), by Caspar David Friedrich