Naginata: Difference between revisions

Galamazoo12 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

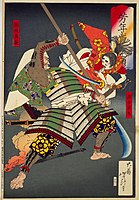

Ergative rlt (talk | contribs) that's obviously a modern depiction of a warrior monk |

||

| (649 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Type of Japanese polearm}} |

|||

[[Image:Samurai_with_Naginata.jpg|thumb|A samurai wielding a naginata]] |

|||

{{Italic title|reason=[[:Category:Japanese words and phrases]]}} |

|||

{{Infobox weapon |

|||

| name = {{Nihongo|Naginata|なぎなた, 薙刀}} |

|||

| image = File:薙刀, Naginata.jpg |

|||

| caption = A ''naginata'' blade forged by Osafune Katsumitsu. [[Muromachi period]], 1503, [[Tokyo National Museum]] |

|||

| type = [[Polearm]] |

|||

| used_by = [[Samurai]], [[Onna-musha]], [[Naginatajutsu]] practitioners |

|||

<!-- Type selection -->| sheath_type = [[Japanese lacquerware|Lacquered wood]] |

|||

| head_type = |

|||

| haft_type = |

|||

| image_size = 350 |

|||

| origin = Japan |

|||

| is_bladed = yes |

|||

<!-- Production history -->| production_date = [[Heian period]] or [[Kamakura period]] until present. |

|||

<!-- General specifications -->| weight = {{Convert|650|g|oz}} and more |

|||

| length = {{Convert|205|-|260|cm|in}} |

|||

| part_length = {{Convert|85|-|100|cm|in}} |

|||

<!-- Bladed weapon specifications -->| blade_type = Curved, single-edged |

|||

| hilt_type = wood, horn, lacquer |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''''naginata''''' ({{linktext|なぎなた}}, {{linktext|薙刀}}) is a [[polearm]] and one of several varieties of traditionally made Japanese blades (''[[Japanese sword|nihontō]]'').<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PtBci2GslUkC&q=nihonto+refers+to&pg=PA150 |title=The Development of Controversies: From the Early Modern Period to Online Discussion Forums, Volume 91 of Linguistic Insights. Studies in Language and Communication|author=Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani|publisher=Peter Lang|year=2008|isbn=978-3-03911-711-6|page=150}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f-RsCs5dJRwC&q=traditionally+made+a+Japanese+sword+nihonto&pg=PA144|title=The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Mythology, Complete Idiot's Guides|author=Evans Lansing Smith, Nathan Robert Brown|publisher=Penguin|year=2008|isbn=978-1-59257-764-4|page=144}}</ref> ''Naginata'' were originally used by the [[samurai]] class of feudal Japan, as well as by [[ashigaru]] (foot soldiers) and [[sōhei]] (warrior monks).<ref name="books.google.com">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P-Nv_LUi6KgC&q=naginata&pg=PA158|title=Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation|author=Thomas A. Green, Joseph R. Svinth|publisher=ABC-CLIO|year=2010|page=158|isbn=9781598842449}}</ref> The naginata is the iconic weapon of the [[onna-musha]], a type of female warrior belonging to the Japanese nobility. A common misconception is that the Naginata is a type of sword, rather than a polearm. |

|||

'''Naginata''' (なぎなた, 長刀 or 薙刀) is a [[pole weapon]] that was traditionally used in [[Japan]] by members of the [[samurai]] class. It has become associated with [[women]] and in modern Japan it is studied by women more than men; whereas in [[Europe]] and [[Australia]]<!-- And not America too? --> naginata is practiced predominantly (but not exclusively) by [[men]]. A naginata consists of a wood shaft with a curved blade on the end; it is similar to the European [[glaive]]. Usually it also had a sword-like guard ([[tsuba]]) between the blade and shaft. |

|||

==Description== |

|||

The martial art of wielding the naginata is called ''[[naginatajutsu|naginata-jutsu]]''. Most naginata practice today is in a modernised form, a [[Gendai Budō|gendai budo]] called ''[[Atarashii naginata]]'', in which competitions also are held. Use of the naginata is also taught within the [[Bujinkan]] and in some [[koryu]] schools. Naginata practitioners may wear a modified form of the protective [[armour]] worn by [[kendo]] practitioners, known as [[bogu]]. |

|||

A ''naginata'' consists of a wooden or metal pole with a curved single-edged blade on the end; it is similar to the Chinese [[guan dao]]<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=mqTP18US1asC&dq=naginata+guan+dao&pg=PA494 ''Encyclopedia technical, historical, biographical and cultural martial arts of the Far East'', Authors Gabrielle Habersetzer , Roland Habersetzer, Publisher Amphora Publishing, 2004], {{ISBN|2-85180-660-2}}, {{ISBN|978-2-85180-660-4}} P.494</ref> or the European [[glaive]].<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=IQ3FAZG94ZsC&dq=naginata+glaive&pg=PA139 ''Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior'', Author Clive Sinclaire, Publisher Globe Pequot, 2004], {{ISBN|1-59228-720-4}}, {{ISBN|978-1-59228-720-8}} P.139</ref> Similar to the katana, naginata often have a round handguard (''[[tsuba]]'') between the blade and shaft, when mounted in a [[koshirae]] (furniture). The 30 cm to 60 cm (11.8 inches to 23.6 inches) ''naginata'' blade is forged in the same manner as traditional [[Japanese sword]]s. The blade has a long tang [[Commons:Category:Nakago (naginata)|(''nakago'')]] which is inserted in the [[Commons:Category:Naginata nagaye (ebu)|shaft]]. |

|||

The blade is removable and is secured by means of a wooden peg called [[Commons:Category:Mekugi|''mekugi'']] (目釘) that passes through a hole ([[Commons:Category:Mekugi-ana|''mekugi-ana'']]) in both the tang and the shaft. |

|||

The shaft ranges from 120 cm to 240 cm (47.2 inches to 94.5 inches) in length and is oval shaped. The area of the shaft where the tang sits is the [[Commons:Category:tachiuchi (tachiuke)|''tachiuchi'' or ''tachiuke'']]. The tachiuchi/tachiuke would be reinforced with metal rings ([[Commons:Category:Naginata dogane (semegane)|''naginata dogane'' or ''semegane'']]), and/or metal sleeves [[Commons:Category:Naginata (sakawa)|(''sakawa'')]] and wrapped with cord ([[Commons:Category:Naginata (san-dan maki)|''san-dan maki'']]). The end of the shaft has a heavy metal end cap ([[Commons:Category:Naginata ishizuki (hirumaki)|''ishizuki'' or ''hirumaki'']]). When not in use the blade would be covered with a [[Commons:Category:Saya (naginata)|wooden sheath]].<ref name="books.google.com"/> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

[[File:Naginata2.JPG|thumb|upright=0.5|Mounting for ''naginata'', [[Edo period]]]] |

|||

The term "naginata" first appeared in the ''[[Kojiki]]'' in 712 CE and was used by [[Sohei]] warrior priests during the [[Nara period|Nara Period]], around 750 CE. It originated from the Chinese Guan Dao. In the [[painting]]s of battlefield scenes made during the [[Tengyo no Ran]] in 936 CE, the naginata can be seen in use. It was in 1086, in the book ''Ōshū Gosannenki'' ("A Diary of Three Years in [[Ōshū]]") that the use of the naginata in combat is first recorded. In this period the naginata was regarded as an extremely effective weapon by warriors. |

|||

[[File:Yōshū_Chikanobu_Tomoe_Gozen.jpg|thumb|[[Tomoe Gozen]], an "[[onna-musha]]", wields a naginata on horseback.]] |

|||

[[File:A Fighting Monk, Military Costumes in Old Japan..jpg|thumb|A Meiji-era depiction of a sōhei (warrior monk) with a naginata]] |

|||

It is assumed that the ''naginata'' was developed from an earlier weapon type of the later 1st millennium AD, the ''[[hoko yari]]''.<ref name="Draeger">{{cite book|last=Draeger|first=David E.|title=Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts|publisher= Kodansha International|year=1981|page=208|isbn=978-0-87011-436-6}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Ratti|first=Oscar|author2=Adele Westbrook|title=Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan|publisher=Castle Books|year=1999|isbn=978-0-7858-1073-5|page=[https://archive.org/details/secretsofsamurai00osca_0/page/241 241]|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/secretsofsamurai00osca_0/page/241}}</ref> Another assumption is that the ''naginata'' was developed by lengthening the hilt of the ''[[tachi]]'' at the end of the Heian period, and it is not certain which theory is correct.<ref name = "toukennagi">[https://web.archive.org/web/20201124014052/https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/25694/ Basic knowledge of naginata and nagamaki.] Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World</ref> |

|||

During the Gempei War ([[1180]]-[[1185]]), in which the [[Taira clan]] was pitted against [[Minamoto no Yoritomo]] of the [[Minamoto clan]], the naginata rose to a position of particularly high esteem. [[Cavalry]] battles had become more important by this time, and the naginata proved excellent at dismounting cavalry and disabling riders. The widespread adoption of the naginata as a battlefield weapon forced the introduction of ''[[Greave|sune-ate]]'' (shin guards) as a part of Japanese armor. The rise of importance for the naginata can be seen as being mirrored by the European [[Pike (weapon)|pike]], another long pole weapon employed against mounted warriors. An excellent example of the role of women in Japanese society and martial culture at this time is [[Hangaku|Itagaki]], who, famous for her naginata skills, led the [[garrison]] of 3,000 warriors stationed at [[Toeizakayama castle]]. Ten thousand [[Hōjō clan]] warriors were dispatched to take the castle, and Itagaki led her troops out of the castle, killing a significant number of the attackers before being overpowered. |

|||

It is generally believed that ''naginata'' first appeared in the [[Heian period]] (794–1185).<ref name ="en20p35"/> The term ''naginata'' first appeared in historical documents in the Heian period. The earliest clear references to ''naginata'' date from 1146.<ref name = "karl F">{{cite book|author1-link=Karl Friday|last=Friday|first=Karl F.|title= Samurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan|url=https://archive.org/details/samuraiwarfarest00frid_779|url-access=limited|year=2004|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0-203-39216-4|page=[https://archive.org/details/samuraiwarfarest00frid_779/page/n100 86]}}</ref> In ''[[Honchō Seiki]]'' compiled from 1150 to 1159 in the late Heian period, it is recorded that Minamoto no Tsunemitsu mentioned that his weapon was a ''naginata''.<ref name ="en20p35">Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p.35. {{ISBN|978-4651200408}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:ShoinNaginata2.jpg|left|thumb|225px|Students at [[Kobe Shoin Women's University]] wearing modern armor for naginata sparring, minus helmet.]] |

|||

In the early Heian period, battles were mainly fought using ''[[yumi]]'' (longbow) on horseback, but in the late Heian period, battles on foot began to increase and ''naginata'' also came to be used on the battlefield. The ''naginata'' was appreciated because it was a weapon that could maintain an optimum distance from the enemy in close combat.<ref name = "toukennagi"/> During the [[Genpei War]] (1180–1185), in which the [[Taira clan]] was pitted against the [[Minamoto clan]], the ''naginata'' rose to a position of particularly high esteem, being regarded as an extremely effective weapon by warriors.<ref name="WBAR">{{cite book|last=Ratti|first=Oscar|author2=Adele Westbrook|title=Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan|publisher=[[Tuttle Publishing]]|year=1991|page=484|isbn=978-0-8048-1684-7}}</ref> ''[[The Tale of the Heike]]'', which records the Genpei War, there are descriptions such as ''ō naginata'' (lit. big ''naginata'') and ''ko naginata'' (lit. little ''naginata''), which show that ''naginata'' of various lengths were used.<ref name ="en20p35"/> The ''naginata'' proved excellent at dismounting cavalry and disabling riders. The widespread adoption of the ''naginata'' as a battlefield weapon forced the introduction of [[greave]]s as a part of [[Japanese armor]]. [[Ōyamazumi Shrine]] houses two ''naginata'' that are said to have been dedicated by [[Tomoe Gozen]] and [[Benkei]] at the end of the Heian period and they are designated as [[Important Cultural Property (Japan)|Important Cultural Property]].<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20210724065108/https://www.touken-world.jp/religious-building/6526/ "Ōyamazumi Shrine"]. Nagoya Token Museum Nagoya Token World.</ref> |

|||

During the [[Edo period|Edo Period]], as the naginata became less useful for men on the battlefield, it became a symbol of the social status of women of the samurai class. A functional naginata was often a traditional part of a samurai daughter's [[dowry]]. Although they did not typically fight as normal soldiers, women of the samurai class were expected to be capable of defending their homes while their husbands were away at war. The naginata was considered one of the weapons most suitable for women, as it allows a woman to keep a male opponent at a distance, where his greater height, weight, and upper body strength offers less of an advantage. |

|||

However, according to [[Karl Friday]], there were various notations for ''naginata'' in the Heian period and the earliest physical evidence for ''naginata'' was in the middle of the Kamakura period, so there is a theory that says when they first appeared is unclear.<ref name = "karl F"/> Earlier 10th through 12th century sources refer to "long swords" that while a common medieval term or orthography for ''naginata'', could also simply be referring to conventional swords; one source describes a ''naginata'' being drawn with the verb {{Nihongo|2=抜く|3=nuku}}, commonly associated with swords, rather than {{Nihongo|2=外す|3=hazusu}}, the verb otherwise used in medieval texts for unsheathing ''naginata''.<ref name = "karl F"/> Some 11th and 12th century mentions of ''hoko'' may actually have been referring to ''naginata''.<ref>Friday (2004), page 87</ref> The commonly assumed association of the ''naginata'' and the ''[[sōhei]]'' is also unclear. Artwork from the late-13th and 14th centuries depict the ''sōhei'' with ''naginata'' but do not appear to place any special significance to it: the weapons appear as just one of a number of others carried by the monks, and are used by ''samurai'' and commoners as well.<ref>{{cite book|last= Adolphson|first=Mikael S.|title=The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sōhei in Japanese History|url= https://archive.org/details/teethclawsbuddha00adol|url-access= limited|year=2007| publisher=University of Hawai'i Press|isbn=978-0-8248-3123-3|pages=[https://archive.org/details/teethclawsbuddha00adol/page/n147 130]–133}}</ref> Depictions of ''naginata''-armed ''sōhei'' in earlier periods were created centuries after the fact, and are likely using the ''naginata'' as a symbol to distinguish the ''sōhei'' from other warriors, rather than giving an accurate portrayal of the events.<ref>Adolphson (2007), pp. 137, 140</ref> |

|||

By the 17th century the rise in popularity of [[firearm]]s caused a great decrease in the appearance of the naginata on the [[battlefield]]. |

|||

After the [[Ōnin War]] (1467–1477) in the [[Muromachi period]], large-scale group battles started in which mobilized {{transliteration|ja|[[ashigaru]]}} (foot soldiers) fought on foot and in close quarters, and {{transliteration|ja|[[yari]]}} (spear), {{transliteration|ja|[[yumi]]}} (longbow), and {{transliteration|ja|[[Tanegashima (gun)|tanegashima]]}} (Japanese matchlock) became the main weapons. This made {{transliteration|ja|naginata}} and {{transliteration|ja|[[tachi]]}} obsolete on the battlefield, and they were often replaced with the {{transliteration|ja|[[nagamaki]]}} and short, lightweight {{transliteration|ja|[[katana]]}}.<ref name = "toukennagi"/><ref name = "toukenssw">[https://web.archive.org/web/20201226054428/https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/45927/ Arms for battle - spears, swords, bows.] Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World</ref><ref name ="en20p42">Kazuhiko Inada (2020), ''Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords''. p42. {{ISBN|978-4651200408}}</ref><ref name="rekishi200940">''歴史人'' September 2020. pp.40-41. {{ASIN|B08DGRWN98}}</ref> |

|||

Due to the influence of [[Westernization]] after the [[Meiji Restoration]] the perceived value of [[martial arts]], the naginata included, dropped severely. It was from this time that the focus of training became the strengthening of the will and the forging of the mind and body. During the [[Shōwa period|Showa period]], naginata training became a part of the [[public school]] system. |

|||

In the [[Edo period]] (1603–1867), the hilts of {{transliteration|ja|naginata}} were often cut off and made into {{transliteration|ja|katana}} or {{nihongo3|short sword||[[wakizashi]]}}. This practice of cutting off the hilt of an {{transliteration|ja|ōdachi}}, {{transliteration|ja|tachi}}, {{transliteration|ja|naginata}}, or {{transliteration|ja|nagamaki}} and remaking it into a shorter {{transliteration|ja|katana}} or {{transliteration|ja|wakizashi}} due to changes in tactics is called {{nihongo3||磨上げ|suriage}} and was common in Japan at the time.<ref name = "toukennagi"/><ref name="nagoyanaga">{{cite web|url=https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/55511/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220118160507/https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/55511/|script-title=ja:長巻とは|language=ja|publisher=The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World|archive-date=18 January 2022|access-date=10 June 2023}}</ref> In Japan there is a saying about swords: "No sword made by modifying a {{transliteration|ja|naginata}} or a {{transliteration|ja|nagamaki}} is dull in cutting" (薙刀(長巻)直しに鈍刀なし). The meaning of this saying is that {{transliteration|ja|naginata}} and {{transliteration|ja|nagamaki}} are equipment for actual combat, not works of art or offerings to the {{transliteration|ja|[[kami]]}}, and that the sharpness and durability of swords made from their modifications have been proven on the battlefield.<ref name="nagoyanaga">{{cite web|url=https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/55511/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220118160507/https://www.touken-world.jp/tips/55511/|script-title=ja:長巻とは|language=ja|publisher=The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World|archive-date=18 January 2022|access-date=10 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://katana-kaitori.com/6789|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230327204541/https://katana-kaitori.com/6789|script-title=ja:薙刀の魅力とは?現代にも受け継がれる長柄武器について解説します|language=ja|publisher=The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World|date=22 July 2022|archive-date=27 March 2023|access-date=10 June 2023}}</ref> |

|||

Martial arts training in Japan was banned for five years by the [[Allies of World War II|Allied Forces]] after Japan's [[surrender]] at the end of [[World War II]]. After the lifting of the ban in [[1950]], a modern form of naginata training, known as ''Atarashii naginata'' (New naginata), was developed. Since World War II, naginata has primarily been practiced as a sport with a particular emphasis on [[etiquette]] and [[discipline]], rather than as military training. |

|||

In the peaceful Edo period, weapons' value as battlefield weapons became diminished and their value for martial arts and self-defense rose. The ''naginata'' was accepted as a status symbol and self-defense weapon for women of nobility, resulting in the image that "the Naginata is the main weapon used by women".<ref name = "toukennagi"/> |

|||

==Construction== |

|||

The naginata, like many weapons, can be customized to fit the build of the bearer. Generally, the naginata shaft is the height of the bearer's body, with the blade mounted atop usually measuring two or three [[shaku]] (one shaku is equivalent to 11.93 inches, or 303 mm) long. Unlike most polearms, the shaft is [[oval]] in cross section to allow easy orientation of the blade, and ranges from 5 to 7 feet (1.5 to 2.1 meters) long. The blade is usually curved, sometimes strongly so, towards the tip. As with Japanese swords, naginata blades were forged blades, made with differing degrees of hardness on the spine and edge to retain a sharp edge but also be able to absorb the stress of impact. Some naginata blades may, in fact, have been recycled [[katana]] blades. |

|||

In the [[Meiji (era)|Meiji era]], it gained popularity along sword martial arts. From the [[Taishō|Taisho era]] to the post-War era, the ''naginata'' became popular as a martial art for women, mainly due to the influence of government policies.<ref name = "toukennagi"/> |

|||

Note also at the opposite end of a naginata, the ''[[ishizuki]]'', (a metal end-cap, often spiked, which functioned as a counterweight to the blade) was attached, rendering the naginata an effective weapon whichever end was put forward. |

|||

Although associated with considerably smaller numbers of practitioners, a number of "koryu bujutsu" systems (traditional martial arts) which include older and more combative forms of ''[[naginatajutsu]]'' remain existent, including Suio Ryu, Araki Ryu, Tendo Ryu, Jikishinkage ryu, Higo Koryu, Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu, Toda-ha Buko Ryu, and Yoshin ryu, some of which have authorized representatives outside Japan. |

|||

In contemporary naginatajutsu, there are two general constructions. The first, the ''[[kihon yo]]'', is carved from one piece of Japanese white oak and is used for the practice of katas (forms). This is quite light, and may or may not feature the tsuba between the blade and shaft sections. The second type, the ''[[shiai yo]]'', uses a similar wooden shaft, but the blade is constructed from bamboo and is replaceable as it can break through hard contact. This type is used in atarashii naginata, the bamboo blade being a lot more forgiving on the target than a wooden or metal blade. |

|||

==Contemporary construction== |

|||

Many of the imitation "naginata" for sale to the public are not actually naginata at all, as may be concluded from the above details on proper construction. Specifically, these imitations have shorter, rounded shafts, very short blades, and screw-together sections. |

|||

In contemporary ''naginatajutsu'', two types of practice ''naginata'' are in common use. |

|||

The ''naginata'' used in ''atarashii naginata'' (新しいなぎなた), the ''shiai-yo'', has an oak shaft and a bamboo "blade" (''habu''). It is used for practice, forms competitions, and sparring. It is between {{convert|210|cm|abbr=on}} and {{convert|225|cm|abbr=on}} in length and must weigh over {{convert|650|g|abbr=on}}.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=P-Nv_LUi6KgC&dq=naginata&pg=PA161 ''Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation'', Thomas A. Green, Joseph R. Svinth, ABC-CLIO, 2010 P.161]</ref> The "blade" is replaceable. They are often broken or damaged during sparring and can be quickly replaced, being attached to the shaft with tape. |

|||

==Usage== |

|||

[[Image:ShoinNaginata1.jpg|right|thumb|225px|Students at Shoin practicing naginata forms]] |

|||

The naginata used by ''koryū'' practitioners has an oak shaft and blade, carved from a single piece of wood, and may incorporate a disc-shaped guard (''[[tsuba]]''). It is called a ''kihon-yo''. |

|||

Naginata can be used to stab, but due to their relatively balanced center of mass, are often spun and turned to proscribe a large radius of reach. The curved blade makes for an effective tool for cutting due to the increased length of cutting surface. In the hands of a skilled practitioner, one 5-foot (1.5 m) tall wielder could conceivably cover and attack in 380 square feet (35 m²) of open, level ground with a 5 foot (1.5 m) shaft, 3 foot (1 m) blade, 3 foot (1 m) reach. Naginatas were often used by foot soldiers to create space on the battlefield. They have several situational advantages over a sword. Their reach was longer, allowing the wielder to keep out of reach of his opponent. The long shaft offered it more leverage in comparison to the hilt of the [[katana]], enabling the naginata to cut more efficiently. The weight of the weapon gave power to strikes and cuts, even though the weight of the weapon is usually thought of as a disadvantage. The weight at the end of the shaft and the shaft itself can be used both offensively and defensively. Swords, on the other hand, can be used to attack faster, have longer cutting edges (and therefore more striking surface and less area to grab), and were able to be more precisely controlled in the hands of an experienced swordsman. |

|||

== |

==Contemporary usage== |

||

{{Main|Naginatajutsu}} |

|||

* [[Tomoe Gozen]] |

|||

[[File:Naginatajutsu_no_5°_Torneio_Brasileiro.jpg|right|thumb|A naginatajutsu tournament in Brazil, organised by the Confederação Brasileira de Kobudo]] |

|||

''Naginata'' can be used to batter, stab, or hook an opponent,<ref name="cats">Katz 2009</ref> but due to their relatively balanced center of mass, are often spun and turned to proscribe a large radius of reach. The curved blade provides a long cutting surface without increasing the overall length of the weapon. |

|||

Historically, the ''naginata'' was often used by foot soldiers to create space on the battlefield. They have several situational advantages over a sword. Their reach is longer, allowing the wielder to keep out of the reach of opponents. The weight of the weapon gave power to strikes and cuts, even though the weight of the weapon is usually thought of as a disadvantage. The weight at the end of the shaft (''ishizuki''), and the shaft itself (''ebu'') can be used offensively and defensively. |

|||

The martial art of wielding the ''naginata'' is known as ''[[naginatajutsu]]''. Most ''naginata'' practice today is in a modernised form, a ''[[Gendai Budō|gendai budō]]'' called ''atarashii Naginata'' ("new Naginata"<ref name="books.google.com"/>), which is organized into regional, national, and international federations, who hold competitions and award ranks. Use of the ''naginata'' is also taught within the ''[[Bujinkan]]'' and in some ''[[koryū]]'' schools such as [[Suiō-ryū|Suio Ryu]] and [[Tendō-ryū]]. |

|||

''Naginata'' practitioners wear an ''[[uwagi]]'', [[Obi (martial arts)|''obi'']], and ''[[hakama]]'', similar to that worn by ''[[kendo]]'' practitioners, although the ''uwagi'' is generally white. For sparring, armor known as ''[[bōgu]]'' is worn. ''Bōgu'' for ''naginatajutsu'' adds {{Nihongo|shin guards|脛当|sune-ate}} and the {{Nihongo|gloves|小手|kote}} have a singulated index finger, unlike the mitten-style gloves used for ''kendo''. |

|||

==Gallery== |

|||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> |

|||

File:Antique_Japanese_naginata_blade.jpg|Antique ''naginata'' blade, [[Tokyo National Museum]] |

|||

File:Naginata(2).JPG|A ''naginata'' made in the [[Kamakura period]] |

|||

File:Naginata1.JPG|Two ''naginata'' |

|||

File:Antique Japanese naginata 1.jpg|''Naginata'' blade and a ''saya'' |

|||

File:Antique Japanese (samurai) naginata blade 5.jpg| |

|||

File:Naginata blade.jpg| |

|||

File:Antique Japanese (samurai) naginata.JPG| |

|||

File:Antique Japanese (samurai) naginata.jpg| |

|||

File:Antique Japanese (samurai) naginata 4.jpg| |

|||

File:Samurai wearing kusari katabira (chain armor).jpg|1870 photograph of samurai and retainers wearing mail armour and holding ''naginata'' |

|||

File:Tomoe-Gozen.jpg|The ''[[onna-musha]]'' [[Tomoe Gozen]] on horseback with a ''naginata'' |

|||

File:NDL-DC 1302763-Tsukioka Yoshitoshi-芳年武者无類 源牛若丸・熊坂長範-明治16-crd.jpg|A duel between [[Minamoto no Yoshitsune|Ushiwakamaru]], who uses a ''[[tachi]]'', and [[Kumasaka]] Chohan, a bandit leader who uses a ''naginata''. From [[Yoshitoshi]]'s [[ukiyo-e]] series, ''Warriors Trembling with Courage''. |

|||

File:Takayama-Ukon.jpg|Samurai [[Takayama Ukon]] with a ''naginata''. Ukiyo-e printed by [[Utagawa Yoshiiku]] (1867). |

|||

File:Yoshitoshi - Ronin lunging forward cph.3g08656.jpg|A [[ronin]] with a ''katana'' and ''naginata'' |

|||

File:Dog - Hata Rokurozaemon with his dog.jpg|Depiction of samurai Hata Rokurozaemon carrying a ''naginata'' |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Guan dao]] |

|||

* [[Budo]] |

|||

* [[Yari]] |

|||

* [[Martial arts]] |

|||

* [[Bisento]] |

* [[Bisento]] |

||

* [[Dao (Chinese sword)|Dadao]] |

|||

* [[Glaive]] |

|||

* [[Guandao]] |

|||

* [[Halberd]] |

* [[Halberd]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Podao]] |

||

* [[Woldo]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==Sources== |

|||

* [[Clive Sinclair]]: ''Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior''. Lyons Press, 2004, {{Isbn|978-1-59228-720-8}}, p. 110. |

|||

* [[George Cameron Stone]], Donald J. LaRocca: ''A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor: In All Countries and in All Times''. Publisher: Courier Dover Publications, 1999, {{Isbn|978-0-486-40726-5}} (Reprint), p. 463f. |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons category}} |

|||

* [http://www.naginata.jp/eng/eng1.html Japan Naginata Union] |

|||

* [http:// |

* [http://international-naginata.org/ International Naginata Federation] {{In lang|ja}} |

||

* [http://www.naginata. |

* [http://www.naginata.jp/english.html All Japan Naginata Federation] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20120204081704/http://home.earthlink.net/~steinrl/nihonto.htm Richard Stein's Japanese sword guide] |

|||

* [http://nawa.wakr.asn.au/ Naginata Association of Western Australia] |

|||

* [http://www.scnf.org/history2.html |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20050802082426/http://www.scnf.org/history2.html Additional History of the Naginata]—Southern California Naginata Federation |

||

* [http://www.koryu.com/guide/naginata.html Naginatajutsu Resources] at Koryu.com |

|||

{{Japanese (samurai) weapons, armour and equipment}} |

|||

{{commonscat}} |

|||

{{Polearms}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Japanese women in warfare|*]] |

[[Category:Japanese women in warfare|*]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Edged and bladed weapons]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Japanese sword types]] |

||

[[Category:Polearms of Japan]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Polearms]] |

||

[[Category:Samurai polearms]] |

|||

[[es:Naginata]] |

|||

[[Category:Sport in Japan]] |

|||

[[fr:Naginata]] |

|||

[[it:Naginata]] |

|||

[[la:Nanguinata]] |

|||

[[ja:薙刀術]] |

|||

[[pl:Naginata]] |

|||

[[ru:Нагината]] |

|||

[[sr:Нагината]] |

|||

[[fi:Naginata]] |

|||

[[sv:Naginata]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 23:17, 5 January 2025

| Naginata (なぎなた, 薙刀) | |

|---|---|

A naginata blade forged by Osafune Katsumitsu. Muromachi period, 1503, Tokyo National Museum | |

| Type | Polearm |

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Service history | |

| Used by | Samurai, Onna-musha, Naginatajutsu practitioners |

| Production history | |

| Produced | Heian period or Kamakura period until present. |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 650 grams (23 oz) and more |

| Length | 205–260 centimetres (81–102 in) |

| Blade length | 85–100 centimetres (33–39 in) |

| Blade type | Curved, single-edged |

| Hilt type | wood, horn, lacquer |

| Scabbard/sheath | Lacquered wood |

The naginata (なぎなた, 薙刀) is a polearm and one of several varieties of traditionally made Japanese blades (nihontō).[1][2] Naginata were originally used by the samurai class of feudal Japan, as well as by ashigaru (foot soldiers) and sōhei (warrior monks).[3] The naginata is the iconic weapon of the onna-musha, a type of female warrior belonging to the Japanese nobility. A common misconception is that the Naginata is a type of sword, rather than a polearm.

Description

[edit]A naginata consists of a wooden or metal pole with a curved single-edged blade on the end; it is similar to the Chinese guan dao[4] or the European glaive.[5] Similar to the katana, naginata often have a round handguard (tsuba) between the blade and shaft, when mounted in a koshirae (furniture). The 30 cm to 60 cm (11.8 inches to 23.6 inches) naginata blade is forged in the same manner as traditional Japanese swords. The blade has a long tang (nakago) which is inserted in the shaft.

The blade is removable and is secured by means of a wooden peg called mekugi (目釘) that passes through a hole (mekugi-ana) in both the tang and the shaft. The shaft ranges from 120 cm to 240 cm (47.2 inches to 94.5 inches) in length and is oval shaped. The area of the shaft where the tang sits is the tachiuchi or tachiuke. The tachiuchi/tachiuke would be reinforced with metal rings (naginata dogane or semegane), and/or metal sleeves (sakawa) and wrapped with cord (san-dan maki). The end of the shaft has a heavy metal end cap (ishizuki or hirumaki). When not in use the blade would be covered with a wooden sheath.[3]

History

[edit]

It is assumed that the naginata was developed from an earlier weapon type of the later 1st millennium AD, the hoko yari.[6][7] Another assumption is that the naginata was developed by lengthening the hilt of the tachi at the end of the Heian period, and it is not certain which theory is correct.[8]

It is generally believed that naginata first appeared in the Heian period (794–1185).[9] The term naginata first appeared in historical documents in the Heian period. The earliest clear references to naginata date from 1146.[10] In Honchō Seiki compiled from 1150 to 1159 in the late Heian period, it is recorded that Minamoto no Tsunemitsu mentioned that his weapon was a naginata.[9]

In the early Heian period, battles were mainly fought using yumi (longbow) on horseback, but in the late Heian period, battles on foot began to increase and naginata also came to be used on the battlefield. The naginata was appreciated because it was a weapon that could maintain an optimum distance from the enemy in close combat.[8] During the Genpei War (1180–1185), in which the Taira clan was pitted against the Minamoto clan, the naginata rose to a position of particularly high esteem, being regarded as an extremely effective weapon by warriors.[11] The Tale of the Heike, which records the Genpei War, there are descriptions such as ō naginata (lit. big naginata) and ko naginata (lit. little naginata), which show that naginata of various lengths were used.[9] The naginata proved excellent at dismounting cavalry and disabling riders. The widespread adoption of the naginata as a battlefield weapon forced the introduction of greaves as a part of Japanese armor. Ōyamazumi Shrine houses two naginata that are said to have been dedicated by Tomoe Gozen and Benkei at the end of the Heian period and they are designated as Important Cultural Property.[12]

However, according to Karl Friday, there were various notations for naginata in the Heian period and the earliest physical evidence for naginata was in the middle of the Kamakura period, so there is a theory that says when they first appeared is unclear.[10] Earlier 10th through 12th century sources refer to "long swords" that while a common medieval term or orthography for naginata, could also simply be referring to conventional swords; one source describes a naginata being drawn with the verb nuku (抜く), commonly associated with swords, rather than hazusu (外す), the verb otherwise used in medieval texts for unsheathing naginata.[10] Some 11th and 12th century mentions of hoko may actually have been referring to naginata.[13] The commonly assumed association of the naginata and the sōhei is also unclear. Artwork from the late-13th and 14th centuries depict the sōhei with naginata but do not appear to place any special significance to it: the weapons appear as just one of a number of others carried by the monks, and are used by samurai and commoners as well.[14] Depictions of naginata-armed sōhei in earlier periods were created centuries after the fact, and are likely using the naginata as a symbol to distinguish the sōhei from other warriors, rather than giving an accurate portrayal of the events.[15]

After the Ōnin War (1467–1477) in the Muromachi period, large-scale group battles started in which mobilized ashigaru (foot soldiers) fought on foot and in close quarters, and yari (spear), yumi (longbow), and tanegashima (Japanese matchlock) became the main weapons. This made naginata and tachi obsolete on the battlefield, and they were often replaced with the nagamaki and short, lightweight katana.[8][16][17][18]

In the Edo period (1603–1867), the hilts of naginata were often cut off and made into katana or wakizashi (short sword). This practice of cutting off the hilt of an ōdachi, tachi, naginata, or nagamaki and remaking it into a shorter katana or wakizashi due to changes in tactics is called suriage (磨上げ) and was common in Japan at the time.[8][19] In Japan there is a saying about swords: "No sword made by modifying a naginata or a nagamaki is dull in cutting" (薙刀(長巻)直しに鈍刀なし). The meaning of this saying is that naginata and nagamaki are equipment for actual combat, not works of art or offerings to the kami, and that the sharpness and durability of swords made from their modifications have been proven on the battlefield.[19][20]

In the peaceful Edo period, weapons' value as battlefield weapons became diminished and their value for martial arts and self-defense rose. The naginata was accepted as a status symbol and self-defense weapon for women of nobility, resulting in the image that "the Naginata is the main weapon used by women".[8]

In the Meiji era, it gained popularity along sword martial arts. From the Taisho era to the post-War era, the naginata became popular as a martial art for women, mainly due to the influence of government policies.[8]

Although associated with considerably smaller numbers of practitioners, a number of "koryu bujutsu" systems (traditional martial arts) which include older and more combative forms of naginatajutsu remain existent, including Suio Ryu, Araki Ryu, Tendo Ryu, Jikishinkage ryu, Higo Koryu, Tenshin Shoden Katori Shinto Ryu, Toda-ha Buko Ryu, and Yoshin ryu, some of which have authorized representatives outside Japan.

Contemporary construction

[edit]In contemporary naginatajutsu, two types of practice naginata are in common use.

The naginata used in atarashii naginata (新しいなぎなた), the shiai-yo, has an oak shaft and a bamboo "blade" (habu). It is used for practice, forms competitions, and sparring. It is between 210 cm (83 in) and 225 cm (89 in) in length and must weigh over 650 g (23 oz).[21] The "blade" is replaceable. They are often broken or damaged during sparring and can be quickly replaced, being attached to the shaft with tape.

The naginata used by koryū practitioners has an oak shaft and blade, carved from a single piece of wood, and may incorporate a disc-shaped guard (tsuba). It is called a kihon-yo.

Contemporary usage

[edit]

Naginata can be used to batter, stab, or hook an opponent,[22] but due to their relatively balanced center of mass, are often spun and turned to proscribe a large radius of reach. The curved blade provides a long cutting surface without increasing the overall length of the weapon.

Historically, the naginata was often used by foot soldiers to create space on the battlefield. They have several situational advantages over a sword. Their reach is longer, allowing the wielder to keep out of the reach of opponents. The weight of the weapon gave power to strikes and cuts, even though the weight of the weapon is usually thought of as a disadvantage. The weight at the end of the shaft (ishizuki), and the shaft itself (ebu) can be used offensively and defensively.

The martial art of wielding the naginata is known as naginatajutsu. Most naginata practice today is in a modernised form, a gendai budō called atarashii Naginata ("new Naginata"[3]), which is organized into regional, national, and international federations, who hold competitions and award ranks. Use of the naginata is also taught within the Bujinkan and in some koryū schools such as Suio Ryu and Tendō-ryū.

Naginata practitioners wear an uwagi, obi, and hakama, similar to that worn by kendo practitioners, although the uwagi is generally white. For sparring, armor known as bōgu is worn. Bōgu for naginatajutsu adds shin guards (脛当, sune-ate) and the gloves (小手, kote) have a singulated index finger, unlike the mitten-style gloves used for kendo.

Gallery

[edit]-

Antique naginata blade, Tokyo National Museum

-

A naginata made in the Kamakura period

-

Two naginata

-

Naginata blade and a saya

-

1870 photograph of samurai and retainers wearing mail armour and holding naginata

-

The onna-musha Tomoe Gozen on horseback with a naginata

-

A duel between Ushiwakamaru, who uses a tachi, and Kumasaka Chohan, a bandit leader who uses a naginata. From Yoshitoshi's ukiyo-e series, Warriors Trembling with Courage.

-

Samurai Takayama Ukon with a naginata. Ukiyo-e printed by Utagawa Yoshiiku (1867).

-

A ronin with a katana and naginata

-

Depiction of samurai Hata Rokurozaemon carrying a naginata

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani (2008). The Development of Controversies: From the Early Modern Period to Online Discussion Forums, Volume 91 of Linguistic Insights. Studies in Language and Communication. Peter Lang. p. 150. ISBN 978-3-03911-711-6.

- ^ Evans Lansing Smith, Nathan Robert Brown (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to World Mythology, Complete Idiot's Guides. Penguin. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-59257-764-4.

- ^ a b c Thomas A. Green, Joseph R. Svinth (2010). Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation. ABC-CLIO. p. 158. ISBN 9781598842449.

- ^ Encyclopedia technical, historical, biographical and cultural martial arts of the Far East, Authors Gabrielle Habersetzer , Roland Habersetzer, Publisher Amphora Publishing, 2004, ISBN 2-85180-660-2, ISBN 978-2-85180-660-4 P.494

- ^ Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior, Author Clive Sinclaire, Publisher Globe Pequot, 2004, ISBN 1-59228-720-4, ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8 P.139

- ^ Draeger, David E. (1981). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. Kodansha International. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6.

- ^ Ratti, Oscar; Adele Westbrook (1999). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Castle Books. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-7858-1073-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Basic knowledge of naginata and nagamaki. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World

- ^ a b c Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p.35. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ a b c Friday, Karl F. (2004). Samurai, Warfare and the State in Early Medieval Japan. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-203-39216-4.

- ^ Ratti, Oscar; Adele Westbrook (1991). Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan. Tuttle Publishing. p. 484. ISBN 978-0-8048-1684-7.

- ^ "Ōyamazumi Shrine". Nagoya Token Museum Nagoya Token World.

- ^ Friday (2004), page 87

- ^ Adolphson, Mikael S. (2007). The Teeth and Claws of the Buddha: Monastic Warriors and Sōhei in Japanese History. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-0-8248-3123-3.

- ^ Adolphson (2007), pp. 137, 140

- ^ Arms for battle - spears, swords, bows. Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum, Touken World

- ^ Kazuhiko Inada (2020), Encyclopedia of the Japanese Swords. p42. ISBN 978-4651200408

- ^ 歴史人 September 2020. pp.40-41. ASIN B08DGRWN98

- ^ a b 長巻とは (in Japanese). The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ 薙刀の魅力とは?現代にも受け継がれる長柄武器について解説します (in Japanese). The Nagoya Japanese Sword Museum Nagoya Touken World. 22 July 2022. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, Thomas A. Green, Joseph R. Svinth, ABC-CLIO, 2010 P.161

- ^ Katz 2009

Sources

[edit]- Clive Sinclair: Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8, p. 110.

- George Cameron Stone, Donald J. LaRocca: A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor: In All Countries and in All Times. Publisher: Courier Dover Publications, 1999, ISBN 978-0-486-40726-5 (Reprint), p. 463f.

External links

[edit]- International Naginata Federation (in Japanese)

- All Japan Naginata Federation

- Richard Stein's Japanese sword guide

- Additional History of the Naginata—Southern California Naginata Federation

- Naginatajutsu Resources at Koryu.com