Black holes in fiction: Difference between revisions

TompaDompa (talk | contribs) →Time dilation: Copyediting. |

|||

| (894 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|none}} |

|||

==Background Science== |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=November 2017}} |

|||

The concept of a body so massive that even light could not escape goes back to the late 18th century. With the development of [[General Relativity]], it was realized that such bodies would have other odd properties. The idea was developed further, though the term '[[black hole]] was only coined in 1967 and did not become the norm until later. These hypothetical objects were also called ''frozen stars''. |

|||

[[File:BH LMC.png|alt=Refer to caption|thumb|Simulated view of a black hole in front of the [[Large Magellanic Cloud]], with [[gravitational lens]]ing visible]] |

|||

{{Spatial anomalies in fiction}} |

|||

[[Black hole]]s, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing—including light—can escape them, have been depicted in fiction since at least the [[pulp era]] of [[science fiction]], before the term ''black hole'' was coined. A common portrayal at the time was of black holes as hazards to spacefarers, a motif that has also recurred in later works. The concept of black holes became popular in science and fiction alike in the 1960s. Authors quickly seized upon the [[General relativity|relativistic]] effect of [[gravitational time dilation]], whereby time passes more slowly closer to a black hole due to its immense gravitational field. Black holes also became a popular means of [[space travel in science fiction]], especially when the notion of [[wormhole]]s emerged as a relatively plausible way to achieve [[faster-than-light]] travel. In this concept, a black hole is connected to its theoretical opposite, a so-called [[white hole]], and as such acts as a gateway to another point in space which might be very distant from the point of entry. More exotically, the point of emergence is occasionally portrayed as another point in time—thus enabling [[time travel]]—or even an entirely [[Parallel universes in fiction|different universe]]. |

|||

More fanciful depictions of black holes that do not correspond to their known or predicted properties also appear. As nothing inside the [[event horizon]]—the distance away from the black hole where the [[escape velocity]] exceeds the [[speed of light]]—can be observed from the outside, authors have been free to employ [[artistic license]] when depicting the interiors of black holes. A small number of works also portray black holes as being sentient. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Roger Zelazny]]'s SF novel ''[[Creatures of Light and Darkness]]'' contains the concept, something called Skagganauk Abyss where there is no space or time. |

|||

Besides [[stellar-mass black hole]]s, [[Supermassive black hole|supermassive]] and especially [[Micro black hole|micro black holes]] also make occasional appearances. Supermassive black holes are a common feature of modern [[space opera]]. Recurring themes in stories depicting micro black holes include [[Black hole starship|spaceship propulsion]], threatening or causing the destruction of the Earth, and serving as a source of gravity in [[Space settlement|outer-space settlements]]. |

|||

The ''[[Black Sun (disambiguation)|Black Sun]]'' in [[Arthur C. Clarke]]'s ''[[The City and the Stars]]'' (1956) is sometimes interpreted as a black hole. It is definitely made so in [[Gregory Benford]]'s ''Beyond the Fall of Night'' (1990).. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Popularisation== |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

As a growing number of scientists began to believe Black Holes were real, and as they began to appear in works of popular science, they also became frequent elements in Science Fiction stories: |

|||

| quote = [V]irtually the whole of [[gravitational physics]] can be understood using [[Newtonian theory]]. As far as real-world [[astrophysics]] goes, the most important exception to this is the existence of black holes. It's probably no coincidence that black holes also happen to be by far the most popular astrophysical phenomena found in [[science fiction]]. |

|||

| author = Andrew May |

|||

| source = ''How Space Physics Really Works: Lessons from Well-Constructed Science Fiction''<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /> |

|||

| width = 390px |

|||

}} |

|||

The general concept of [[black hole]]s, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing—including light—can escape them, was first proposed by [[John Michell]] in 1783 and developed further in the framework of [[Albert Einstein]]'s theory of [[general relativity]] by [[Karl Schwarzschild]] in 1916.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> Serious scientific attention remained relatively limited until the 1960s, the same decade the term ''black hole'' was coined,{{Efn|Often credited to [[John Archibald Wheeler]], who maintained that he merely popularized the term. See {{Section link|Black hole|Etymology}} for further details.}} though objects with the overall characteristics of black holes<!-- Stableford says that "The idea of black holes had been vaguely anticipated in such constructs as [...]", Westfahl says "one occasionally encounters equivalent sorts of celestial bodies in science fiction stories of the pulp era", and Langford says "Pathological stars with some properties of black holes were imagined before the term was coined." --> had made appearances in fiction decades earlier during the [[pulp era]] of science fiction.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=Westfahl |first=Gary |title=[[Science Fiction Literature through History: An Encyclopedia]] |date=2021 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-4408-6617-3 |pages=159–162 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |author-link=Gary Westfahl |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WETPEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA159}}</ref><ref name="StablefordBlackHole">{{Cite book |last=Stableford |first=Brian |title=[[Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia]] |date=2006 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-415-97460-8 |pages=65–67 |language=en |chapter=Black Hole |author-link=Brian Stableford |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uefwmdROKTAC&pg=PA65}}</ref><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=Langford |first=David |title=[[The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders]] |date=2005 |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-32951-7 |editor-last=Westfahl |editor-first=Gary |editor-link=Gary Westfahl |pages=89–91 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |author-link=David Langford |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/greenwoodencyclo0000unse_k2b9/page/89/mode/2up}}</ref><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="LuokkalaBlackHoles">{{multiref2|{{Cite book |last=Luokkala |first=Barry B. |title=Exploring Science Through Science Fiction |date=2013 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-1-4614-7891-1 |pages=31–34 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |author-link=Barry Luokkala |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rQwJAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA31}}|{{Cite book |last=Luokkala |first=Barry B. |title=Exploring Science Through Science Fiction |date=2019 |publisher=Springer Nature |isbn=978-3-030-29393-2 |edition=Second |pages=35–39 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |author-link=Barry Luokkala |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GJO7DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA35}} |

|||

}}</ref> Examples of this include [[E. E. Smith]]'s 1928 novel ''[[The Skylark of Space]]'' with its "black sun", {{Interlanguage link|Frank K. Kelly|WD=Q81196257}}'s 1935 short story "[[Starship Invincible]]" with its "Hole in Space"<!-- Capitalized thusly by the sources. -->, and [[Nat Schachner]]'s 1938 short story "[[Negative Space (short story)|Negative Space]]"—all of which portray the black holes {{lang|fr|[[wikt:avant_la_lettre|avant la lettre]]}} as hazards to spacefarers.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /> Later works that nevertheless predate the adoption of the current terminology include [[Fred Saberhagen]]'s 1965 short story "[[Masque of the Red Shift]]" with its "hypermass" and the 1967 ''[[Star Trek: The Original Series|Star Trek]]'' episode "[[Tomorrow Is Yesterday]]" with its "black star".<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="LuokkalaBlackHoles" /> |

|||

== Time dilation == |

|||

* [[Larry Niven]] wrote several short stories based on [[Micro black hole|mini-black holes]], including ''[[The Hole Man]]'' (1974) and ''[[The Borderland of Sol]]'' in ''[[Tales of Known Space]]'', 1975. |

|||

Once black holes gained mainstream popularity, many of the early works featuring black holes focused on the concept of [[gravitational time dilation]], whereby time passes more slowly closer to a black hole due to the effects of general relativity.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> One consequence of this is that the process of crossing the [[event horizon]]—the distance away from the black hole where the [[escape velocity]] exceeds the [[speed of light]]—appears to an outside observer to take an infinite amount of time.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> In [[Poul Anderson]]'s 1968 short story "[[Kyrie (short story)|Kyrie]]", a [[Telepathy|telepathic]] scream from a being falling into a black hole thus becomes drawn out for eternity.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=Edwards |first=Malcolm |author-link=Malcolm Edwards |title=[[The Science Fiction Encyclopedia]] |date=1979 |publisher=[[Doubleday (publisher)|Doubleday]] |others=Associate Editor: [[John Clute]]; Technical Editor: Carolyn Eardley; Contributing Editors: [[Malcolm Edwards]], [[Brian Stableford]] |isbn=978-0-385-14743-9 |editor-last=Nicholls |editor-first=Peter |editor-link=Peter Nicholls (writer) |edition=First US |series=Dolphin Books |location=Garden City, New York |pages=75–76 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sciencefictionen0000unse/page/74/mode/2up}}</ref><ref>{{multiref2|{{Cite book |last=Nahin |first=Paul J. |author-link=Paul J. Nahin |title=Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction |date=2001 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-0-387-98571-8 |edition=Second |pages=542–543 |language=en |chapter=Tech Note 11: Time and Gravity |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=39KQY1FnSfkC&pg=PA542}}|{{Cite book |last=Nahin |first=Paul J. |author-link=Paul J. Nahin |title=Time Machine Tales: The Science Fiction Adventures and Philosophical Puzzles of Time Travel |date=2017 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-3-319-48862-2 |series=Science and Fiction |pages=146 |language=en |chapter=Time Dilation |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-48864-6_3 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4NfJDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA146}}}}</ref> Similarly, a spaceship appears forever immovable at the event horizon in [[Brian Aldiss]]'s 1976 short story "[[The Dark Soul of the Night]]",<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> and in [[Frederik Pohl]]'s 1977 novel ''[[Gateway (novel)|Gateway]]'', an astronaut is wracked with [[survivor's guilt]] over the deaths of his companions during an encounter with a black hole, compounded by the process appearing to still be ongoing.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> Later sequels in Pohl's [[Heechee Saga]], from the 1980 novel ''[[Beyond the Blue Event Horizon]]'' onward, portray time dilation being exploited by [[Extraterrestrial life|aliens]] who reside near a black hole to experience the passage of time more slowly than the rest of the universe;<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheTimeFactor">{{Cite book |last1=Lambourne |first1=R. J. |title=Close Encounters?: Science and Science Fiction |last2=Shallis |first2=M. J. |last3=Shortland |first3=M. |date=1990 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-0-85274-141-2 |pages=60–62 |language=en |chapter=The Time Factor |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z7iaZENKoV4C&pg=PA60<!-- Also available at https://archive.org/details/closeencounterss0000lamb/page/60/mode/2up -->}}</ref> other aliens do likewise in [[David Brin]]'s 1984 short story "[[The Crystal Spheres]]" while waiting for the universe to be more filled with life, and in [[Alastair Reynolds]]'s 2000 novel ''[[Revelation Space]]'', they do it to hide.<ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /> In [[Bill Johnson (author)|Bill Johnson]]'s 1982 short story "[[Meet Me at Apogee]]", travel to various levels of time dilation is commercialized, used by people with incurable diseases among others.<ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles">{{Cite web |last=Fraknoi |first=Andrew |author-link=Andrew Fraknoi |date=January 2024 |title=Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index |url=https://astrosociety.org/file_download/inline/7b5edc23-7a89-46c1-a6b3-33a30ed4c876 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240210011957/https://astrosociety.org/file_download/inline/7b5edc23-7a89-46c1-a6b3-33a30ed4c876 |archive-date=2024-02-10 |archive-format=PDF |access-date=2024-06-21 |website=[[Astronomical Society of the Pacific]] |pages=3–4 |format=PDF |edition=7.3}}</ref> In the 2014 film ''[[Interstellar (film)|Interstellar]]'', a [[Blanet|planet orbits a black hole]] so closely that it experiences extreme time dilation, with time passing approximately 60,000<!-- 7 years / 1 hour ≈ 60,000 --> times slower than on Earth.<ref name="LuokkalaBlackHoles" /><ref name="UnderstandingBlackHolesThroughScienceFiction" /> |

|||

* [[Frederik Pohl]]'s [[Heechee]] series includes black holes of several sorts. This starts with ''[[Gateway (novel)|Gateway]]'' (1976). |

|||

* [[Stephen Baxter]]'s 2004 novel ''[[Exultant (Stephen Baxter)|Exultant]]'' features a war between humans and aliens based around a [[Supermassive black hole|supermassive black hole]] at the core of our galaxy. |

|||

== |

== Space travel == |

||

{{See also|Space travel in science fiction|Wormholes in fiction}} |

|||

Black holes have also been portrayed as ways to travel through space.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /><ref name="MammothBlackHole" /> In particular, they often serve as a means to achieve [[faster-than-light]] travel.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /><ref name="MammothBlackHole" /> The proposed mechanism involves travelling through the [[Gravitational singularity|singularity]] at the center of a black hole and emerging at some other, perhaps very distant, place in the universe.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> More exotically, the point of emergence is occasionally portrayed as another point in time—thus enabling [[time travel]]—or even an entirely [[Parallel universes in fiction|different universe]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=May |first=Andrew |chapter=A Few Words about Black Holes |title=How Space Physics Really Works: Lessons from Well-Constructed Science Fiction |publisher=Springer |year=2023 |isbn=978-3-031-33950-9 |series=Science and Fiction |pages=52–56 |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-33950-9_2 |author-link=<!-- No article at present (July 2023); Ph.D. in astrophysics from Manchester University; not one of the people listed at [[Andrew May]] --> |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zKXIEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA52}}</ref><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=Bloom |first=Steven D. |title=The Physics and Astronomy of Science Fiction: Understanding Interstellar Travel, Teleportation, Time Travel, Alien Life and Other Genre Fixtures |date=2016 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-0-7864-7053-2 |pages=38–43 |language=en |chapter=Stellar Evolution: Supernovas, Pulsars, and Black Holes |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8NbIDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA38}}</ref> To explain why the immense gravitational field of the black hole does not crush the travellers and their vessels, the special theorized properties of [[rotating black hole]]s are sometimes invoked by authors;<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> astrophysicists [[Steven D. Bloom]] and [[Andrew May (astrophysicist)|Andrew May]] argue that the strong [[tidal force]]s would nevertheless invariably be fatal, May pointing specifically to [[spaghettification]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles" /> According to ''[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]]'', early stories employing black holes for this purpose tended to use alternative terminology to obfuscate the underlying issues.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> Thus, [[Joe Haldeman]]'s 1974 [[fix-up]] novel ''[[The Forever War]]'', where a network of black holes is used for interstellar warfare, calls them "[[collapsar]]s", while [[George R. R. Martin]]'s 1972 short story "[[The Second Kind of Loneliness]]" has a "nullspace vortex".<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /> |

|||

* In ''[[Star Trek: The Motion Picture]]'' (1979), it is stated that ''Voyager 6'' disappeared into "what they used to call a black hole". |

|||

* ''[[Black Hole (2006 film)|Black Hole]]'' is the title of a science fiction movie released in 2006. It is unrelated to the 1979 film. |

|||

* In ''[[Event Horizon]]'' (1997), a spaceship is created to travel faster than light by a machine that creates an artificial black hole to travel to Alpha Centauri. The ship actually passes into an unknown dimension. |

|||

Speculation that black holes might be connected to their hypothetical opposites, [[white hole]]s, soon followed—the resulting arrangement being known as a [[wormhole]].<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEWhiteHoles">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2021 |title=White Holes |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/white_holes |access-date=2024-06-24 |edition=4th |author1-last=Stableford |author1-first=Brian |author1-link=Brian Stableford |author2-last=Nicholls |author2-first=Peter |author2-link=Peter Nicholls (writer) |author3-last=Langford |author3-first=David |author3-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref><ref name="SFEWormholes">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2016 |title=Wormholes |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/wormholes |access-date=2024-06-24 |edition=4th |author1-last=Langford |author1-first=David |author1-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> Wormholes were appealing to writers due to their relative theoretical plausibility as a means of faster-than-light travel,<ref name="SFE1979BlackHoles" /> and they were further popularized by speculative works of non-fiction such as [[Adrian Berry, 4th Viscount Camrose|Adrian Berry]]'s 1977 book ''[[The Iron Sun: Crossing the Universe Through Black Holes]]''.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> Black holes and associated wormholes thus quickly became commonplace in fiction; according to [[science fiction scholar]] [[Brian Stableford]], writing in the 2006 work ''[[Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia]]'', "wormholes became the most fashionable mode of [[interstellar travel]] in the last decades of the twentieth century".<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> [[Ian Wallace (author)|Ian Wallace]]'s 1979 novel ''[[Heller's Leap]]'' is a [[murder mystery]] involving a journey through a black hole.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Hall |first=Loay |date=October 1979<!-- see https://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pl.cgi?339178 for further information --> |editor-last=Barron |editor-first=Neil |editor-link=Neil Barron |title=Review: ''Heller's Leap'' by Ian Wallace |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K9P1T0doSpkC&pg=PA121 |magazine=[[Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review]] |pages=121 |volume=1 |issue=9 |issn=0163-4348}}</ref> [[Joan D. Vinge]]'s 1980 novel ''[[The Snow Queen (Vinge novel)|The Snow Queen]]'' is set on a [[circumbinary planet]] where a black hole between the [[binary star]]s serves as the gateway between the system and the outside world,<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Stableford |first=Brian |author-link=Brian Stableford |title=The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places |date=1999 |publisher=Wonderland Press |isbn=978-0-684-84958-4 |pages=303 |chapter=Tiamat |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofscie0000unse/page/302/mode/2up}}</ref> while [[Paul Preuss (author)|Paul Preuss]]'s 1980 novel ''[[The Gates of Heaven (novel)|The Gates of Heaven]]'' and its 1981 follow-up<!-- The two "[comprise] a very loose sequence", according to SFE. --> ''[[Re-Entry (novel)|Re-Entry]]'' feature black holes that are used for travel through both space and time.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2022 |title=Preuss, Paul |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/preuss_paul |access-date=2024-06-25 |edition=4th |author1-last=Clute |author1-first=John |author1-link=John Clute |author2-last=Langford |author2-first=David |author2-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> In the 1989 [[anime]] film ''[[Garaga (film)|Garaga]]'', human [[Space colonization|colonization of the cosmos]] is enabled by interstellar gateways associated with black holes.<ref name="SFEGaraga">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2021 |title=Garaga |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/garaga |access-date=2024-07-07 |edition=4th |author1-last=Pearce |author1-first=Steven |author1-link=<!-- No article at present (July 2024) --> |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> The entire Earth is transported through a wormhole in [[Roger MacBride Allen]]'s 1990 novel ''[[The Ring of Charon]]''.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> Travel between universes is depicted in Pohl and [[Jack Williamson]]'s 1991 novel ''[[The Singers of Time]]'',<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> the concept having earlier made a more fanciful appearance in the 1975 film ''[[The Giant Spider Invasion]]'', where the spiders of the title arrive at Earth through a black hole.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2017 |title=Giant Spider Invasion, The |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/giant_spider_invasion_the |access-date=2024-06-25 |edition=4th |author1-last=Nicholls |author1-first=Peter |author1-link=Peter Nicholls (writer) |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> In the 2009 film ''[[Star Trek (2009 film)|Star Trek]]'', a black hole created to neutralize a [[supernova]] threat has the side-effect of transporting two nearby spaceships into the past, where they end up [[Alternate history|altering the course of history]].<ref name="LuokkalaBlackHoles" /> In [[Bolivian science fiction]] writer [[Giovanna Rivero]]'s 2012 novel ''[[Helena 2022: La vera crónica de un naufragio en el tiempo]]'', a spaceship ends up in 1630s Italy as a result of an accidental encounter with a black hole.<ref name="SFEBolivia">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2020 |title=Bolivia |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/bolivia |access-date=2024-07-07 |edition=4th |author1-last=Rodrigo-Mendizábal |author1-first=Iván |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> |

|||

==Television== |

|||

* In the television SF-adventure series ''[[Andromeda (TV series)|Andromeda]]'' (2000), a black hole slows time for the hero, allowing him to survive into a new era. |

|||

== Small and large == |

|||

* Several adventures in the British television series [[Doctor Who]] feature black holes, notably [[The Impossible Planet]] and [[The Satan Pit]]. |

|||

Black holes need not necessarily be [[Stellar-mass black hole|stellar-mass]]; the decisive factor is whether sufficient mass is contained within a small enough space—the [[Schwarzschild radius]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="LuokkalaBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles" /> The principal mechanism of black hole formation is the [[gravitational collapse]] of a [[Stellar evolution#Massive stars|massive star]], but other origins have been hypothesized, including so-called [[primordial black hole]]s forming shortly after the [[Big Bang]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles" /> Primordial black holes could theoretically be of virtually any conceivable size, though the smallest ones would by now have evaporated into nothing due to the [[Quantum mechanics|quantum mechanical]] effect known as [[Hawking radiation]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /> |

|||

* In the [[Blake's Seven]] story "Breakdown" the [[Liberator]] travels through a black hole. |

|||

*In the [[Stargate SG-1]] episode [[A Matter of Time]] a wormhole is opened to a planet near the event horizon of a black hole. |

|||

{{Anchor|Micro black holes|Quantum black holes}}The concept of [[micro black hole]]s was first theorized in the 1970s, and quickly became popular in science fiction.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /> In [[Larry Niven]]'s 1974 short story "[[The Hole Man]]", a microscopic black hole is used as a murder weapon by exploiting the tidal effects at short range,<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /> and in Niven's 1975 short story "[[The Borderland of Sol]]", one is used by [[space pirate]]s to capture spaceships.<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /> Small black holes are [[Black hole starship|used to power spaceship propulsion]] in [[Arthur C. Clarke]]'s 1975 novel ''[[Imperial Earth]]'', [[Charles Sheffield]]'s 1978 short story "[[Killing Vector]]", and the 1997 film ''[[Event Horizon (film)|Event Horizon]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2022 |title=Black Holes |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/black_holes |access-date=2023-12-26 |edition=4th |author1-last=Stableford |author1-first=Brian |author1-link=Brian Stableford |author2-last=Nicholls |author2-first=Peter |author2-link=Peter Nicholls (writer) |author3-last=Langford |author3-first=David |author3-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /><ref name="MammothBlackHole" /> Artificial black holes that are created unintentionally at nuclear facilities appear in [[Michael McCollum]]'s 1979 short story "[[Scoop (short story)|Scoop]]" and [[Martin Caidin]]'s 1980 novel ''[[Star Bright (novel)|Star Bright]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /> In [[David Langford]]'s 1982 novel ''[[The Space Eater]]'', a small black hole is used as a weapon against a rebellious planet.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Nicoll |first=James |author-link=James Nicoll |date=2000-05-07 |title=Lost Voices 18: ''The Space Eater'' by David Langford |url=https://jamesdavisnicoll.com/mists-of-time/lost-voices-18-the-space-eater-by-david-langford |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231003033049/https://jamesdavisnicoll.com/mists-of-time/lost-voices-18-the-space-eater-by-david-langford |archive-date=2023-10-03 |access-date=2024-06-28 |website=James Nicoll Reviews}}</ref> Earth is endangered by miniature black holes in [[Gregory Benford]]'s 1985 novel ''[[Artifact (novel)|Artifact]]'', [[Thomas Thurston Thomas]]'s 1986 novel ''[[The Doomsday Effect]]'', and Brin's 1990 novel ''[[Earth (Brin novel)|Earth]]'', and the planet's destruction in this way forms part of the backstory in [[Dan Simmons]]'s 1989 novel ''[[Hyperion (Simmons novel)|Hyperion]]'',<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /> while the [[Moon]]'s destruction by a small black hole is depicted in [[Paul J. McAuley]]'s 1990 short story "[[How We Lost the Moon]]" and is suspected to have occurred in [[Neal Stephenson]]'s 2015 novel ''[[Seveneves]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /> Small black holes are used as a way to provide an [[artificial gravity]] of sorts by placing them inside [[Space settlement|inhabited structures]] or [[Colonization of the asteroid belt|settled asteroids]] in Sheffield's 1989 novel ''[[Proteus Unbound]]'', Reynolds's 2008 novel ''[[House of Suns]]'', and [[Iain M. Banks]]'s 2010 novel ''[[Surface Detail]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> The titular material in [[Wil McCarthy]]'s 2000 novel ''[[The Collapsium]]'' is made up of a lattice of micro black holes and makes [[teleportation]] possible.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="MammothBlackHole" /> |

|||

{{Anchor|Supermassive black holes}}At the opposite end of the spectrum, black holes can have masses comparable to that of an entire [[galaxy]].<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /> [[Supermassive black hole]]s, with masses that can be in excess of billions of times the [[Solar mass|mass of the Sun]], are thought to [[Central massive object|exist in the center of most galaxies]].<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles" /> Sufficiently large and massive black holes would have a low average [[density]] and could theoretically contain intact stars and planets within their event horizons.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles">{{Cite book |last=Langford |first=David |author-link=David Langford |title=[[The Science in Science Fiction]] |date=1983 |publisher=Knopf |isbn=0-394-53010-1 |editor-last=Nicholls |editor-first=Peter |editor-link=Peter Nicholls (writer) |location=New York |pages=84–85 |chapter=Stars, neutron stars and black holes |oclc=8689657 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/scienceinscience00nich/page/84/mode/2up}}</ref> An enormous yet low-density black hole of this kind appears in [[Barry N. Malzberg]]'s 1975 novel ''[[Galaxies (novel)|Galaxies]]''.<ref name="TheTimeFactor" /><ref name="TheScienceInScienceFictionStarsNeutronStarsAndBlackHoles" /> In Benford's [[Galactic Center Saga]], starting with the 1977 novel ''[[In the Ocean of Night]]'', the vicinity of the supermassive black hole at the [[Galactic Center]] of the [[Milky Way]] is an attractive destination for spacefaring civilizations due to the high concentration of stars that can serve as sources of energy in the region; a similar use is found for a regular-sized black hole in Benford's 1986 short story "[[As Big as the Ritz]]", where its [[accretion disk]] provides ample [[solar energy]] for a space habitat.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Stableford |first=Brian |author-link=Brian Stableford |title=The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places |date=1999 |publisher=Wonderland Press |isbn=978-0-684-84958-4 |pages=52–53 |chapter=Brotherworld |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofscie0000unse/page/52/mode/2up}}</ref> McAuley's 1991 novel ''[[Eternal Light (novel)|Eternal Light]]'' involves a journey to the central supermassive black hole to investigate a [[hypervelocity star]] on a trajectory towards the [[Solar System]].<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Trudel |first=Jean-Louisliv |author-link=Jean-Louis Trudel |date=2000 |title=Review: ''Eternal Light'' |url=https://www.sfsite.com/07a/el84.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000901045854/https://www.sfsite.com/07a/el84.htm |archive-date=2000-09-01 |access-date=2024-06-27 |website=[[SF Site]]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Mann |first=George |author-link=George Mann (writer) |title=The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction |date=2001 |publisher=Carroll & Graf Publishers |isbn=978-0-7867-0887-1 |location=New York |pages=200 |language=en |chapter=McAuley, Paul J. |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/mammothencyclope00mann/page/200/mode/2up}}</ref> Says ''The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'', "the [[Sagittarius A*|immense black hole at the galactic core]] has become almost a [[cliché]] of contemporary [[space opera]]" such as [[Greg Egan]]'s 2008 novel ''[[Incandescence (novel)|Incandescence]]''.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> |

|||

== Hazards to spacefarers == |

|||

The pulp-era motif of black holes posing danger to spacefarers resurfaced decades later following the popularization of black holes in fiction.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /> In the 1975 ''[[Space: 1999]]'' episode "[[Black Sun (Space 1999)|Black Sun]]", one threatens to destroy the Moon [[World ship|as it travels through space]]; the episode was one of those included in [[Edwin Charles Tubb]]'s 1975 [[novelization]] ''[[Breakaway (novel)|Breakaway]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="BloomSupernovasPulsarsAndBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Muir |first=John Kenneth |author-link=John Kenneth Muir |title=Exploring Space: 1999: An Episode Guide and Complete History of the Mid-1970s Science Fiction Television Series |date=2015 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-0-7864-5527-0 |pages=27–30 |language=en |chapter=Black Sun |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5E8-mw_OrnoC&pg=PA28}}</ref> In [[Isaac Asimov]]'s 1976 short story "[[Old-fashioned (short story)|Old-fashioned]]", astronauts surmise that an unseen object keeping them in orbit must be a modestly-sized black hole, having wreaked havoc with their spaceship through tidal forces.<ref name="May2023AFewWordsAboutBlackHoles" /> In [[Edward Bryant]]'s 1976 novel ''[[Cinnabar (novel)|Cinnabar]]'', a computer self-destructs by intentionally entering a black hole.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /> In [[Mildred Downey Broxon]]'s 1978 short story "[[Singularity (short story)|Singularity]]", scientists study a civilization on a planet that will shortly be destroyed by an approaching black hole.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=D'Ammassa |first=Don |author-link=Don D'Ammassa |title=Twentieth-century Science-fiction Writers |date=1986 |publisher=St. James Press |isbn=978-0-912289-27-4 |editor-last=Smith |editor-first=Curtis C. |pages=85–86 |language=en |chapter=Broxon, Mildred Downey |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/twentiethcentury0000unse_v9c2/page/86/mode/2up}}</ref> [[John Varley (author)|John Varley]]'s 1978 short story "[[The Black Hole Passes]]" depicts an outpost in the [[Oort cloud]] being imperilled by a small black hole.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=Nicoll |first=James |author-link=James Nicoll |date=2015-07-05 |title=The tragedy of John Varley |url=https://jamesdavisnicoll.com/review/the-tragedy-of-john-varley |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240125022058/https://jamesdavisnicoll.com/review/the-tragedy-of-john-varley |archive-date=2024-01-25 |access-date=2024-06-29 |website=James Nicoll Reviews}}</ref> In [[Stephen Baxter (author)|Stephen Baxter]]'s 1993 short story "[[Pilot (short story)|Pilot]]", a spaceship [[Penrose process|extracts energy]] from a rotating black hole's [[ergosphere]] to widen its event horizon and cause a pursuer to fall into it<!-- As the story itself (see https://www.stephen-baxter.com/stories.html#pilot) puts it: "[The spaceship] took so much spin from the black hole that [it] almost stopped it rotating altogether. It became a Schwarzschild hole. Without spin, its event horizon expanded, filling up the equatorial belt where the ergosphere had been. [The spaceship] had clipped the ergosphere safely. The [pursuer], following [its] trajectory exactly, had fallen straight into the expanded event horizon." -->.<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /> Black holes also appear as obstacles in the 2007 video game ''[[Super Mario Galaxy]]''.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Armelli |first=Paolo |date=2014-01-27 |title=I buchi neri non esistono, ma non ditelo agli autori di fantascienza |trans-title=Black holes do not exist, but don't tell science fiction authors that |url=https://www.wired.it/play/libri/2014/01/27/buchi-neri-hawking-fantascienza/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240301102111/https://www.wired.it/play/libri/2014/01/27/buchi-neri-hawking-fantascienza/ |archive-date=2024-03-01 |access-date=2024-07-07 |website=[[Wired (magazine)|Wired]] Italia |language=it-IT}}</ref> |

|||

== Interior == |

|||

Black holes have been depicted with varying degrees of accuracy to the scientific understanding of them. Because what lies beyond the event horizon is unknown and by definition unobservable from outside, authors have been free to employ [[artistic license]] when depicting the interiors of black holes.<ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="UnderstandingBlackHolesThroughScienceFiction">{{Cite web |last=Johnson |first=David Kyle |author-link=David Kyle Johnson |date=2019-06-19 |title=Understanding Black Holes Through Science Fiction |url=https://www.sciphijournal.org/index.php/2019/06/19/understanding-black-holes-through-science-fiction/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200920043430/https://www.sciphijournal.org/index.php/2019/06/19/understanding-black-holes-through-science-fiction/ |archive-date=2020-09-20 |access-date=2021-09-16 |website=[[Sci Phi Journal]] |language=en-GB}}</ref><ref name="MammothBlackHole" /> The 1979 film ''[[The Black Hole (1979 film)|The Black Hole]]'', noted for its inaccurate portrayal of the known properties of black holes discernible from without<!-- Stableford comments that it "pays scant attention to the scientific niceties of the concept", Langford calls it "execrated" and writes that it "abandons all connection with speculative physics", Lambourne et al. say "Many of the scientific prerequisites for the behaviour of objects in the vicinity of black holes are manifest, but not always correctly.", and Johnson comments that "The science in the film is monumentally inaccurate, especially regarding how it depicts its black hole." -->, depicts the inside as an otherworldly place bearing the hallmarks of [[Christianity|Christian]] conceptions of the [[afterlife]].<ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="TheTimeFactor" /><ref name="UnderstandingBlackHolesThroughScienceFiction" /> In Benford's 1990 novel ''[[Beyond the Fall of Night]]'', a sequel to Clarke's 1948 novel ''[[Against the Fall of Night]]'', the inside of a black hole is used as a prison, a role it also serves in [[Alan Moore]] and [[Dave Gibbons]]'s 1985 [[Superman]] comic book story "[[For the Man Who Has Everything]]".<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /> Alien lifeforms inhabit the interior of a black hole in McCarthy's 1995 novel ''[[Flies from the Amber]]''.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="StablefordBlackHole" /> Expeditions into black holes to explore the interior are depicted in [[Geoffrey A. Landis]]'s 1998 short story "[[Approaching Perimelasma]]" and Egan's 1998 short story "[[The Planck Dive]]".<ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="FraknoiBlackHoles" /> |

|||

== Sentient == |

|||

{{See also|Stars in fiction#Sentient|Sun in fiction#Sentient|Extrasolar planets in fiction#Living}} |

|||

{{Anchor|Living}}In much the same way as stars—and, to a lesser extent, planets—have been [[Anthropomorphism|anthropomorphized]] as living and thinking beings, so have black holes.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFELivingWorlds">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2022 |title=Living Worlds |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/living_worlds |access-date=2024-06-30 |edition=4th |author1-last=Stableford |author1-first=Brian |author1-link=Brian Stableford |author2-last=Langford |author2-first=David |author2-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> An intelligent, talking black hole appears in Varley's 1977 short story "[[Lollipop and the Tar Baby]]".<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref>{{Cite web |date=1986-08-01 |title=Review: ''Worlds Apart: An Anthology of Lesbian and Gay Science Fiction and Fantasy'' |url=https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/a/camilla-eric-garber-lyn-paleo-eds-decarnin/worlds-apart-an-anthology-of-lesbian-and-gay-sc/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240630211505/https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/a/camilla-eric-garber-lyn-paleo-eds-decarnin/worlds-apart-an-anthology-of-lesbian-and-gay-sc/ |archive-date=2024-06-30 |access-date=2024-06-30 |website=[[Kirkus Reviews]] |language=en}}</ref> In Sheffield's ''Proteus Unbound'', microscopic black holes are determined to contain intelligence through signals emanating from them.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEInformationTheory">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2015 |title=Information Theory |encyclopedia=[[The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction]] |url=https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/information_theory |access-date=2024-06-30 |edition=4th |author1-last=Wessells |author1-first=Henry |author2-last=Langford |author2-first=David |author2-link=David Langford |editor1-last=Clute |editor1-first=John |editor1-link=John Clute |editor2-last=Langford |editor2-first=David |editor2-link=David Langford |editor3-last=Sleight |editor3-first=Graham |editor3-link=Graham Sleight}}</ref> In Benford's 2000 novel ''[[Eater (novel)|Eater]]'', a black hole that is sentient as a result of electromagnetic interactions in its accretion disk seeks to devour the Solar System.<ref name="WestfahlBlackHoles" /><ref name="GreenwoodBlackHoles" /><ref name="SFEBlackHoles" /><ref name="MammothBlackHole">{{Cite book |last=Mann |first=George |title=The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction |date=2001 |publisher=Carroll & Graf Publishers |isbn=978-0-7867-0887-1 |location=New York |pages=468–469 |language=en |chapter=Black Hole |author-link=George Mann (writer) |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/mammothencyclope00mann/page/468/mode/2up}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

<imagemap> |

|||

*[[Black holes]] (the science behind it all) |

|||

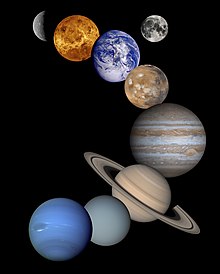

File:Solar system.jpg|alt=A photomontage of the eight planets and the Moon|thumb|Clicking on a planet leads to the article about its depiction in fiction. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

circle 1250 4700 650 [[Neptune in fiction]] |

|||

circle 2150 4505 525 [[Uranus in fiction]] |

|||

circle 2890 3960 610 [[Saturn in fiction]] |

|||

circle 3450 2880 790 [[Jupiter in fiction]] |

|||

circle 3015 1770 460 [[Mars in fiction]] |

|||

circle 2370 1150 520 [[Earth in science fiction]] |

|||

circle 3165 590 280 [[Moon in science fiction]] |

|||

circle 1570 785 475 [[Venus in fiction]] |

|||

circle 990 530 320 [[Mercury in fiction]] |

|||

</imagemap> |

|||

* [[Neutron stars in fiction]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Supernovae in fiction]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Notelist}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* {{Cite book |last=Bly |first=Robert W. |author-link=Robert W. Bly |title=The Science in Science Fiction: 83 SF Predictions That Became Scientific Reality |date=2005 |publisher=[[BenBella Books]] |others=Consulting Editor: [[James E. Gunn|James Gunn]] |isbn=978-1-932100-48-8 |pages=67–74 |language=en |chapter=Black Holes |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/scienceinscience0000blyr/page/66/mode/2up}} |

|||

{{Astronomical locations in fiction}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Science fiction}} |

|||

*[http://library.thinkquest.org/C0110369/Scifi.htm The Truth About Black Holes: Science Fiction] |

|||

{{Black holes}} |

|||

*[http://blackholes.stardate.org/basics/basic.php?id=1 Black Holes: Stranger Than Fiction] |

|||

{{Portal bar|Astronomy|Stars|Spaceflight|Outer space|Solar System}} |

|||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Fiction about black holes| ]] |

||

[[Category:Black holes|Fiction]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 19:21, 10 November 2024

| Spatial anomalies in fiction |

|---|

|

Black holes in fiction • Portable hole • Teleportation in fiction • Wormholes in fiction • Stargate • Warp drive • Hyperspace • Time travel in fiction |

|

|

Black holes, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing—including light—can escape them, have been depicted in fiction since at least the pulp era of science fiction, before the term black hole was coined. A common portrayal at the time was of black holes as hazards to spacefarers, a motif that has also recurred in later works. The concept of black holes became popular in science and fiction alike in the 1960s. Authors quickly seized upon the relativistic effect of gravitational time dilation, whereby time passes more slowly closer to a black hole due to its immense gravitational field. Black holes also became a popular means of space travel in science fiction, especially when the notion of wormholes emerged as a relatively plausible way to achieve faster-than-light travel. In this concept, a black hole is connected to its theoretical opposite, a so-called white hole, and as such acts as a gateway to another point in space which might be very distant from the point of entry. More exotically, the point of emergence is occasionally portrayed as another point in time—thus enabling time travel—or even an entirely different universe.

More fanciful depictions of black holes that do not correspond to their known or predicted properties also appear. As nothing inside the event horizon—the distance away from the black hole where the escape velocity exceeds the speed of light—can be observed from the outside, authors have been free to employ artistic license when depicting the interiors of black holes. A small number of works also portray black holes as being sentient.

Besides stellar-mass black holes, supermassive and especially micro black holes also make occasional appearances. Supermassive black holes are a common feature of modern space opera. Recurring themes in stories depicting micro black holes include spaceship propulsion, threatening or causing the destruction of the Earth, and serving as a source of gravity in outer-space settlements.

Early depictions

[edit][V]irtually the whole of gravitational physics can be understood using Newtonian theory. As far as real-world astrophysics goes, the most important exception to this is the existence of black holes. It's probably no coincidence that black holes also happen to be by far the most popular astrophysical phenomena found in science fiction.

The general concept of black holes, objects whose gravity is so strong that nothing—including light—can escape them, was first proposed by John Michell in 1783 and developed further in the framework of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916.[2][3][4][5] Serious scientific attention remained relatively limited until the 1960s, the same decade the term black hole was coined,[a] though objects with the overall characteristics of black holes had made appearances in fiction decades earlier during the pulp era of science fiction.[2][3][4][5][6] Examples of this include E. E. Smith's 1928 novel The Skylark of Space with its "black sun", Frank K. Kelly's 1935 short story "Starship Invincible" with its "Hole in Space", and Nat Schachner's 1938 short story "Negative Space"—all of which portray the black holes avant la lettre as hazards to spacefarers.[2][3] Later works that nevertheless predate the adoption of the current terminology include Fred Saberhagen's 1965 short story "Masque of the Red Shift" with its "hypermass" and the 1967 Star Trek episode "Tomorrow Is Yesterday" with its "black star".[4][6]

Time dilation

[edit]Once black holes gained mainstream popularity, many of the early works featuring black holes focused on the concept of gravitational time dilation, whereby time passes more slowly closer to a black hole due to the effects of general relativity.[3][5] One consequence of this is that the process of crossing the event horizon—the distance away from the black hole where the escape velocity exceeds the speed of light—appears to an outside observer to take an infinite amount of time.[4][7] In Poul Anderson's 1968 short story "Kyrie", a telepathic scream from a being falling into a black hole thus becomes drawn out for eternity.[4][7][8] Similarly, a spaceship appears forever immovable at the event horizon in Brian Aldiss's 1976 short story "The Dark Soul of the Night",[3][7] and in Frederik Pohl's 1977 novel Gateway, an astronaut is wracked with survivor's guilt over the deaths of his companions during an encounter with a black hole, compounded by the process appearing to still be ongoing.[4][7] Later sequels in Pohl's Heechee Saga, from the 1980 novel Beyond the Blue Event Horizon onward, portray time dilation being exploited by aliens who reside near a black hole to experience the passage of time more slowly than the rest of the universe;[2][4][5][9] other aliens do likewise in David Brin's 1984 short story "The Crystal Spheres" while waiting for the universe to be more filled with life, and in Alastair Reynolds's 2000 novel Revelation Space, they do it to hide.[10] In Bill Johnson's 1982 short story "Meet Me at Apogee", travel to various levels of time dilation is commercialized, used by people with incurable diseases among others.[10] In the 2014 film Interstellar, a planet orbits a black hole so closely that it experiences extreme time dilation, with time passing approximately 60,000 times slower than on Earth.[6][11]

Space travel

[edit]Black holes have also been portrayed as ways to travel through space.[5][7][12][13] In particular, they often serve as a means to achieve faster-than-light travel.[3][5][7][13] The proposed mechanism involves travelling through the singularity at the center of a black hole and emerging at some other, perhaps very distant, place in the universe.[5][7] More exotically, the point of emergence is occasionally portrayed as another point in time—thus enabling time travel—or even an entirely different universe.[1][5][14] To explain why the immense gravitational field of the black hole does not crush the travellers and their vessels, the special theorized properties of rotating black holes are sometimes invoked by authors;[5][7] astrophysicists Steven D. Bloom and Andrew May argue that the strong tidal forces would nevertheless invariably be fatal, May pointing specifically to spaghettification.[1][14] According to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, early stories employing black holes for this purpose tended to use alternative terminology to obfuscate the underlying issues.[5] Thus, Joe Haldeman's 1974 fix-up novel The Forever War, where a network of black holes is used for interstellar warfare, calls them "collapsars", while George R. R. Martin's 1972 short story "The Second Kind of Loneliness" has a "nullspace vortex".[5][10][12]

Speculation that black holes might be connected to their hypothetical opposites, white holes, soon followed—the resulting arrangement being known as a wormhole.[2][3][15][16] Wormholes were appealing to writers due to their relative theoretical plausibility as a means of faster-than-light travel,[7] and they were further popularized by speculative works of non-fiction such as Adrian Berry's 1977 book The Iron Sun: Crossing the Universe Through Black Holes.[3][5] Black holes and associated wormholes thus quickly became commonplace in fiction; according to science fiction scholar Brian Stableford, writing in the 2006 work Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia, "wormholes became the most fashionable mode of interstellar travel in the last decades of the twentieth century".[3][5] Ian Wallace's 1979 novel Heller's Leap is a murder mystery involving a journey through a black hole.[5][17] Joan D. Vinge's 1980 novel The Snow Queen is set on a circumbinary planet where a black hole between the binary stars serves as the gateway between the system and the outside world,[5][12][18] while Paul Preuss's 1980 novel The Gates of Heaven and its 1981 follow-up Re-Entry feature black holes that are used for travel through both space and time.[3][4][19] In the 1989 anime film Garaga, human colonization of the cosmos is enabled by interstellar gateways associated with black holes.[20] The entire Earth is transported through a wormhole in Roger MacBride Allen's 1990 novel The Ring of Charon.[3][5] Travel between universes is depicted in Pohl and Jack Williamson's 1991 novel The Singers of Time,[5] the concept having earlier made a more fanciful appearance in the 1975 film The Giant Spider Invasion, where the spiders of the title arrive at Earth through a black hole.[4][21] In the 2009 film Star Trek, a black hole created to neutralize a supernova threat has the side-effect of transporting two nearby spaceships into the past, where they end up altering the course of history.[6] In Bolivian science fiction writer Giovanna Rivero's 2012 novel Helena 2022: La vera crónica de un naufragio en el tiempo, a spaceship ends up in 1630s Italy as a result of an accidental encounter with a black hole.[22]

Small and large

[edit]Black holes need not necessarily be stellar-mass; the decisive factor is whether sufficient mass is contained within a small enough space—the Schwarzschild radius.[1][5][6][14] The principal mechanism of black hole formation is the gravitational collapse of a massive star, but other origins have been hypothesized, including so-called primordial black holes forming shortly after the Big Bang.[1][12][14] Primordial black holes could theoretically be of virtually any conceivable size, though the smallest ones would by now have evaporated into nothing due to the quantum mechanical effect known as Hawking radiation.[1][3][5][12]

The concept of micro black holes was first theorized in the 1970s, and quickly became popular in science fiction.[4][5][12] In Larry Niven's 1974 short story "The Hole Man", a microscopic black hole is used as a murder weapon by exploiting the tidal effects at short range,[1][3][10] and in Niven's 1975 short story "The Borderland of Sol", one is used by space pirates to capture spaceships.[4][10][12] Small black holes are used to power spaceship propulsion in Arthur C. Clarke's 1975 novel Imperial Earth, Charles Sheffield's 1978 short story "Killing Vector", and the 1997 film Event Horizon.[2][3][5][10][13] Artificial black holes that are created unintentionally at nuclear facilities appear in Michael McCollum's 1979 short story "Scoop" and Martin Caidin's 1980 novel Star Bright.[2][3] In David Langford's 1982 novel The Space Eater, a small black hole is used as a weapon against a rebellious planet.[2][3][23] Earth is endangered by miniature black holes in Gregory Benford's 1985 novel Artifact, Thomas Thurston Thomas's 1986 novel The Doomsday Effect, and Brin's 1990 novel Earth, and the planet's destruction in this way forms part of the backstory in Dan Simmons's 1989 novel Hyperion,[2][3][4] while the Moon's destruction by a small black hole is depicted in Paul J. McAuley's 1990 short story "How We Lost the Moon" and is suspected to have occurred in Neal Stephenson's 2015 novel Seveneves.[2][5][10] Small black holes are used as a way to provide an artificial gravity of sorts by placing them inside inhabited structures or settled asteroids in Sheffield's 1989 novel Proteus Unbound, Reynolds's 2008 novel House of Suns, and Iain M. Banks's 2010 novel Surface Detail.[2][5] The titular material in Wil McCarthy's 2000 novel The Collapsium is made up of a lattice of micro black holes and makes teleportation possible.[3][4][5][13]

At the opposite end of the spectrum, black holes can have masses comparable to that of an entire galaxy.[1] Supermassive black holes, with masses that can be in excess of billions of times the mass of the Sun, are thought to exist in the center of most galaxies.[5][14] Sufficiently large and massive black holes would have a low average density and could theoretically contain intact stars and planets within their event horizons.[5][12] An enormous yet low-density black hole of this kind appears in Barry N. Malzberg's 1975 novel Galaxies.[9][12] In Benford's Galactic Center Saga, starting with the 1977 novel In the Ocean of Night, the vicinity of the supermassive black hole at the Galactic Center of the Milky Way is an attractive destination for spacefaring civilizations due to the high concentration of stars that can serve as sources of energy in the region; a similar use is found for a regular-sized black hole in Benford's 1986 short story "As Big as the Ritz", where its accretion disk provides ample solar energy for a space habitat.[2][3][24] McAuley's 1991 novel Eternal Light involves a journey to the central supermassive black hole to investigate a hypervelocity star on a trajectory towards the Solar System.[3][25][26] Says The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, "the immense black hole at the galactic core has become almost a cliché of contemporary space opera" such as Greg Egan's 2008 novel Incandescence.[5]

Hazards to spacefarers

[edit]The pulp-era motif of black holes posing danger to spacefarers resurfaced decades later following the popularization of black holes in fiction.[2][3] In the 1975 Space: 1999 episode "Black Sun", one threatens to destroy the Moon as it travels through space; the episode was one of those included in Edwin Charles Tubb's 1975 novelization Breakaway.[2][14][27] In Isaac Asimov's 1976 short story "Old-fashioned", astronauts surmise that an unseen object keeping them in orbit must be a modestly-sized black hole, having wreaked havoc with their spaceship through tidal forces.[1] In Edward Bryant's 1976 novel Cinnabar, a computer self-destructs by intentionally entering a black hole.[2][4] In Mildred Downey Broxon's 1978 short story "Singularity", scientists study a civilization on a planet that will shortly be destroyed by an approaching black hole.[3][28] John Varley's 1978 short story "The Black Hole Passes" depicts an outpost in the Oort cloud being imperilled by a small black hole.[3][10][29] In Stephen Baxter's 1993 short story "Pilot", a spaceship extracts energy from a rotating black hole's ergosphere to widen its event horizon and cause a pursuer to fall into it.[3][10] Black holes also appear as obstacles in the 2007 video game Super Mario Galaxy.[30]

Interior

[edit]Black holes have been depicted with varying degrees of accuracy to the scientific understanding of them. Because what lies beyond the event horizon is unknown and by definition unobservable from outside, authors have been free to employ artistic license when depicting the interiors of black holes.[5][11][13] The 1979 film The Black Hole, noted for its inaccurate portrayal of the known properties of black holes discernible from without, depicts the inside as an otherworldly place bearing the hallmarks of Christian conceptions of the afterlife.[3][4][9][11] In Benford's 1990 novel Beyond the Fall of Night, a sequel to Clarke's 1948 novel Against the Fall of Night, the inside of a black hole is used as a prison, a role it also serves in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's 1985 Superman comic book story "For the Man Who Has Everything".[2][5] Alien lifeforms inhabit the interior of a black hole in McCarthy's 1995 novel Flies from the Amber.[2][3] Expeditions into black holes to explore the interior are depicted in Geoffrey A. Landis's 1998 short story "Approaching Perimelasma" and Egan's 1998 short story "The Planck Dive".[4][10]

Sentient

[edit]In much the same way as stars—and, to a lesser extent, planets—have been anthropomorphized as living and thinking beings, so have black holes.[2][31] An intelligent, talking black hole appears in Varley's 1977 short story "Lollipop and the Tar Baby".[2][4][5][32] In Sheffield's Proteus Unbound, microscopic black holes are determined to contain intelligence through signals emanating from them.[2][4][5][33] In Benford's 2000 novel Eater, a black hole that is sentient as a result of electromagnetic interactions in its accretion disk seeks to devour the Solar System.[2][4][5][13]

See also

[edit]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Often credited to John Archibald Wheeler, who maintained that he merely popularized the term. See Black hole § Etymology for further details.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i May, Andrew (2023). "A Few Words about Black Holes". How Space Physics Really Works: Lessons from Well-Constructed Science Fiction. Science and Fiction. Springer. pp. 52–56. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-33950-9_2. ISBN 978-3-031-33950-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Westfahl, Gary (2021). "Black Holes". Science Fiction Literature through History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 159–162. ISBN 978-1-4408-6617-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Stableford, Brian (2006). "Black Hole". Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 65–67. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Langford, David (2005). "Black Holes". In Westfahl, Gary (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 89–91. ISBN 978-0-313-32951-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Stableford, Brian; Nicholls, Peter; Langford, David (2022). "Black Holes". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e

- Luokkala, Barry B. (2013). "Black Holes". Exploring Science Through Science Fiction. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-1-4614-7891-1.

- Luokkala, Barry B. (2019). "Black Holes". Exploring Science Through Science Fiction (Second ed.). Springer Nature. pp. 35–39. ISBN 978-3-030-29393-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Edwards, Malcolm (1979). "Black Holes". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). The Science Fiction Encyclopedia. Dolphin Books. Associate Editor: John Clute; Technical Editor: Carolyn Eardley; Contributing Editors: Malcolm Edwards, Brian Stableford (First US ed.). Garden City, New York: Doubleday. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-385-14743-9.

- ^

- Nahin, Paul J. (2001). "Tech Note 11: Time and Gravity". Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction (Second ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 542–543. ISBN 978-0-387-98571-8.

- Nahin, Paul J. (2017). "Time Dilation". Time Machine Tales: The Science Fiction Adventures and Philosophical Puzzles of Time Travel. Science and Fiction. Springer. p. 146. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-48864-6_3. ISBN 978-3-319-48862-2.

- ^ a b c Lambourne, R. J.; Shallis, M. J.; Shortland, M. (1990). "The Time Factor". Close Encounters?: Science and Science Fiction. CRC Press. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-0-85274-141-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fraknoi, Andrew (January 2024). "Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index" (PDF). Astronomical Society of the Pacific (7.3 ed.). pp. 3–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Johnson, David Kyle (19 June 2019). "Understanding Black Holes Through Science Fiction". Sci Phi Journal. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Langford, David (1983). "Stars, neutron stars and black holes". In Nicholls, Peter (ed.). The Science in Science Fiction. New York: Knopf. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-394-53010-1. OCLC 8689657.

- ^ a b c d e f Mann, George (2001). "Black Hole". The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 468–469. ISBN 978-0-7867-0887-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Bloom, Steven D. (2016). "Stellar Evolution: Supernovas, Pulsars, and Black Holes". The Physics and Astronomy of Science Fiction: Understanding Interstellar Travel, Teleportation, Time Travel, Alien Life and Other Genre Fixtures. McFarland. pp. 38–43. ISBN 978-0-7864-7053-2.

- ^ Stableford, Brian; Nicholls, Peter; Langford, David (2021). "White Holes". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Langford, David (2016). "Wormholes". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Hall, Loay (October 1979). Barron, Neil (ed.). "Review: Heller's Leap by Ian Wallace". Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Review. Vol. 1, no. 9. p. 121. ISSN 0163-4348.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (1999). "Tiamat". The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places. Wonderland Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-684-84958-4.

- ^ Clute, John; Langford, David (2022). "Preuss, Paul". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Pearce, Steven (2021). "Garaga". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter (2017). "Giant Spider Invasion, The". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Rodrigo-Mendizábal, Iván (2020). "Bolivia". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Nicoll, James (7 May 2000). "Lost Voices 18: The Space Eater by David Langford". James Nicoll Reviews. Archived from the original on 3 October 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Stableford, Brian (1999). "Brotherworld". The Dictionary of Science Fiction Places. Wonderland Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-684-84958-4.

- ^ Trudel, Jean-Louisliv (2000). "Review: Eternal Light". SF Site. Archived from the original on 1 September 2000. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Mann, George (2001). "McAuley, Paul J.". The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7867-0887-1.

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth (2015). "Black Sun". Exploring Space: 1999: An Episode Guide and Complete History of the Mid-1970s Science Fiction Television Series. McFarland. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-0-7864-5527-0.

- ^ D'Ammassa, Don (1986). "Broxon, Mildred Downey". In Smith, Curtis C. (ed.). Twentieth-century Science-fiction Writers. St. James Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-912289-27-4.

- ^ Nicoll, James (5 July 2015). "The tragedy of John Varley". James Nicoll Reviews. Archived from the original on 25 January 2024. Retrieved 29 June 2024.

- ^ Armelli, Paolo (27 January 2014). "I buchi neri non esistono, ma non ditelo agli autori di fantascienza" [Black holes do not exist, but don't tell science fiction authors that]. Wired Italia (in Italian). Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Stableford, Brian; Langford, David (2022). "Living Worlds". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ "Review: Worlds Apart: An Anthology of Lesbian and Gay Science Fiction and Fantasy". Kirkus Reviews. 1 August 1986. Archived from the original on 30 June 2024. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Wessells, Henry; Langford, David (2015). "Information Theory". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 30 June 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Bly, Robert W. (2005). "Black Holes". The Science in Science Fiction: 83 SF Predictions That Became Scientific Reality. Consulting Editor: James Gunn. BenBella Books. pp. 67–74. ISBN 978-1-932100-48-8.