Atari, Inc.: Difference between revisions

m It was defunt in 1984 Tag: Reverted |

Far larger than many companies. Singling out Apple adds nothing to the article. |

||

| (63 intermediate revisions by 31 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Short description|American video game developer (1972–1992)}} |

||

{{about|the first company named Atari|information on the Atari brand and its history |Atari|the current company|Atari, Inc. (1993–present)}} |

{{about|the first company named Atari|information on the Atari brand and its history |Atari|the current company|Atari, Inc. (1993–present)}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2017}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2017}} |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| logo_size = 175 |

| logo_size = 175 |

||

| logo_caption = The Atari logo, also known as the "Fuji" |

| logo_caption = The Atari logo, also known as the "Fuji" |

||

| fate = All operating divisions sold off in 1984–85. Merged into parent company in 1992. |

|||

| fate = Home console and computer business sold to [[Jack Tramiel]], becoming [[Atari Corporation]]. Arcade business retained by [[Warner Communications|Warner]] and renamed to [[Atari Games]]. |

|||

| successors = {{unbulleted list|Atari Games|[[Atari Corporation]]}} |

| successors = {{unbulleted list|[[Atari Games]]|[[Atari Corporation]]}} |

||

| foundation = {{Start date and age|1972|06|27}} |

| foundation = {{Start date and age|1972|06|27}} |

||

| defunct = {{End date and age| |

| defunct = {{End date and age|1992|06|26}} |

||

| location = {{unbulleted list|[[Sunnyvale, California|Sunnyvale]], [[California]], [[United States]]|[[New York City]], [[New York (state)|New York]], United States}} |

| location = {{unbulleted list|[[Sunnyvale, California|Sunnyvale]], [[California]], [[United States]]|[[New York City]], [[New York (state)|New York]], United States}} |

||

| industry = [[Video game industry|Video games]] |

| industry = [[Video game industry|Video games]] |

||

| founders = {{unbulleted list|[[Nolan Bushnell]]|[[Ted Dabney]]}} |

| founders = {{unbulleted list|[[Nolan Bushnell]]|[[Ted Dabney]]}} |

||

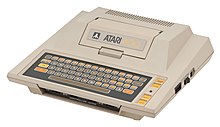

| products = {{unbulleted list|[[Pong]]|[[Atari 2600]]|[[Atari 8-bit |

| products = {{unbulleted list|[[Pong]]|[[Atari 2600]]|[[Atari 8-bit computers]]|[[Atari 5200]]}} |

||

| num_employees = <!--peak number of employees--> |

| num_employees = <!--peak number of employees--> |

||

| parent = [[Warner Communications]] ( |

| parent = [[Warner Communications]] (1976–1990) <br> [[Time Warner]] (1990–1992) |

||

| subsid = [[Chuck E. Cheese]] (1977–1978) <br> [[Kee Games]] (1973–1978) |

| subsid = [[Chuck E. Cheese]] (1977–1978) <br> [[Kee Games]] (1973–1978) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

From 1978 through 1982, Atari continued to expand at a great pace and was the leading company in the growing video game industry. Its arcade games such as ''[[Asteroids (video game)|Asteroids]]'' helped to usher in a [[golden age of arcade video games|golden age of arcade games]] from 1979 to 1983, while the arcade conversion of [[Taito]]'s ''[[Space Invaders]]'' for the VCS became the console's system seller and [[killer application]]. Atari's success drew new console manufacturers to the market, including [[Mattel Electronics]] and [[Coleco]], and fostered [[third-party developer]]s such as [[Activision]] and [[Imagic]]. |

From 1978 through 1982, Atari continued to expand at a great pace and was the leading company in the growing video game industry. Its arcade games such as ''[[Asteroids (video game)|Asteroids]]'' helped to usher in a [[golden age of arcade video games|golden age of arcade games]] from 1979 to 1983, while the arcade conversion of [[Taito]]'s ''[[Space Invaders]]'' for the VCS became the console's system seller and [[killer application]]. Atari's success drew new console manufacturers to the market, including [[Mattel Electronics]] and [[Coleco]], and fostered [[third-party developer]]s such as [[Activision]] and [[Imagic]]. |

||

Looking to stave off new competition in 1982, Atari leaders made |

Looking to stave off new competition in 1982, Atari leaders made decisions that resulted in overproduction of units and games that did not meet sales expectations. Atari had also ventured into the [[home computer]] market with their first [[Atari 8-bit computers|8-bit computers]], but their products did not fare as well as their competitors'. Atari lost more than {{USD|530 million}} in 1983, leading to Kassar's resignation and the appointment of [[James J. Morgan]] as CEO. Morgan attempted to turn Atari around with layoffs and other cost-cutting efforts, but the company's financial hardships had already reverberated through the industry, leading to the [[Video game crash of 1983|1983 crash]] that devastated the U.S. video game market. |

||

Warner Communications sold the home console and computer division of Atari to [[Jack Tramiel]] in July 1984, who then renamed his company [[Atari Corporation]]. Atari, Inc. was renamed Atari Games, Inc. after the sale. In 1985, Warner formed a new corporation jointly with Namco, [[Atari Games|AT Games, Inc.]], which acquired the coin-operated assets of Atari Games, Inc. |

Warner Communications sold the home console and computer division of Atari to [[Jack Tramiel]] in July 1984, who then renamed his company [[Atari Corporation]]. Atari, Inc. was renamed Atari Games, Inc. after the sale. In 1985, Warner formed a new corporation jointly with Namco, [[Atari Games|AT Games, Inc.]], which acquired the coin-operated assets of Atari Games, Inc. AT Games was subsequently renamed Atari Games Corporation. Atari Games, Inc. was then renamed Atari Holdings, Inc. and remained a non-operating subsidiary of Warner Communications and its successor, Time Warner, until being merged back into the parent company in 1992. |

||

=={{anchor|Origin}}Origins== |

=={{anchor|Origin}}Origins== |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

While studying at the [[University of Utah]], electrical engineering student [[Nolan Bushnell]] had a part-time job at an [[amusement arcade]], where he became familiar with arcade [[electro-mechanical game]]s. He watched customers play and helped maintain the machinery, while learning how it worked and developing his understanding of how the game business operates.<ref name="NGen23">{{cite magazine |title=The Great Videogame Swindle? |magazine=[[Next Generation (magazine)|Next Generation]] |issue=23 |publisher=[[Imagine Media]] |date=November 1996 |pages=211–229 |url=https://archive.org/details/NextGeneration23Nov1996P2/page/n72}}</ref> |

While studying at the [[University of Utah]], electrical engineering student [[Nolan Bushnell]] had a part-time job at an [[amusement arcade]], where he became familiar with arcade [[electro-mechanical game]]s. He watched customers play and helped maintain the machinery, while learning how it worked and developing his understanding of how the game business operates.<ref name="NGen23">{{cite magazine |title=The Great Videogame Swindle? |magazine=[[Next Generation (magazine)|Next Generation]] |issue=23 |publisher=[[Imagine Media]] |date=November 1996 |pages=211–229 |url=https://archive.org/details/NextGeneration23Nov1996P2/page/n72}}</ref> |

||

In 1968, Bushnell graduated, became an employee of [[Ampex]] in San Francisco and worked alongside [[Ted Dabney]]. The two found they had shared interests and became friends. |

In 1968, Bushnell graduated, became an employee of [[Ampex]] in San Francisco and worked alongside [[Ted Dabney]]. The two found they had shared interests and became friends. Bushnell shared with Dabney his gaming-pizza parlor idea, and had taken him to the computer lab at [[Stanford University centers and institutes|Stanford Artificial Intelligence Laboratory]] to see the games on those systems.<ref name="edge">{{cite magazine | title = The Untold Atari Story | first= Leonard | last = Herman | date = April 2009 | volume =200 | magazine = [[Edge (magazine)|Edge]] | pages = 94–99 }}</ref> They jointly developed the concept of using a standalone computer system with a monitor and attaching a coin slot to it to play games on.<ref name="edge"/> |

||

To create the game, Bushnell and Dabney decided to start a partnership called Syzygy Engineering, each putting in {{USD|250}} of their own funds to support it.<ref name="edge"/> They had also asked fellow Ampex employee Larry Bryan to participate, and while he had been on board with their ideas, he backed out when asked to contribute financially to starting the company.<ref name="rise and fall chp2">{{cite book | title= |

To create the game, Bushnell and Dabney decided to start a partnership called Syzygy Engineering in 1971, each putting in {{USD|250}} of their own funds to support it.<ref name="edge"/><ref>{{cite video|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=763CFRuxovo|date=November 24, 2022|title=The Evolution of Video Games: Pong's 50-Year Legacy|author=The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age|work=[[YouTube]]|access-date=November 5, 2024|url-status=live|archive-date=July 31, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240731201714/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=763CFRuxovo}}</ref> They had also asked fellow Ampex employee Larry Bryan to participate, and while he had been on board with their ideas, he backed out when asked to contribute financially to starting the company.<ref name="rise and fall chp2">{{cite book | title= Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari | first= Scott |last= Cohen | date = 1984 | publisher =[[McGraw-Hill]] | isbn =9780070115439| chapter=Chapter 2 | pages=15–24 }}</ref> |

||

Bushnell and Dabney worked with [[Nutting Associates]] to manufacture their product. Dabney developed a method of using video circuitry components to mimic functions of a computer for a much cheaper cost and a smaller space. Bushnell and Dabney used this to develop a variation on ''[[Spacewar!]]'' called ''[[Computer Space]]'' where the player shot at two [[UFO]]s. Nutting manufactured the game. While they were developing this, they joined Nutting as engineers, but they also made sure that Nutting placed a "Syzygy Engineered" label on the control panel of each ''Computer Space'' game sold to reflect their work in the game.<ref name="edge"/><ref name="syzygy engineering">{{cite web |

Bushnell and Dabney worked with [[Nutting Associates]] to manufacture their product. Dabney developed a method of using video circuitry components to mimic functions of a computer for a much cheaper cost and a smaller space. Bushnell and Dabney used this to develop a variation on ''[[Spacewar!]]'' called ''[[Computer Space]]'' where the player shot at two [[UFO]]s. Nutting manufactured the game. While they were developing this, they joined Nutting as engineers, but they also made sure that Nutting placed a "Syzygy Engineered" label on the control panel of each ''Computer Space'' game sold to reflect their work in the game.<ref name="edge"/><ref name="syzygy engineering">{{cite web |

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

| title = Al Alcorn Interview |

| title = Al Alcorn Interview |

||

| date = March 11, 2008 |

| date = March 11, 2008 |

||

| url=http://retro.ign.com/articles/858/858351p1.html |

| url = http://retro.ign.com/articles/858/858351p1.html |

||

| access-date = September 11, 2008 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| archive-date = February 10, 2012 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120210151258/http://retro.ign.com/articles/858/858351p1.html |

|||

| url-status = live |

|||

| ⚫ | }}</ref><ref name="nolanmagnavox">{{cite web |author=Ador Yano |url=http://www.ralphbaer.com/video_game_history.htm |title=Video game history |publisher=Ralphbaer.com |access-date=November 29, 2012 |archive-date=December 23, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111223011401/http://www.ralphbaer.com/video_game_history.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="1up">{{cite web|url=http://www.1up.com/do/feature?pager.offset=3&cId=3159462 |title=Videogames Turn 40 Years Old |publisher=1up |url-status=dead |archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20160522220814/http://www.1up.com/do/feature?pager.offset=3&cId=3159462 |archive-date=May 22, 2016 |df=mdy }}</ref> which would go on to be named ''[[Pong]]''. Bushnell had Alcorn use Dabney's video circuit concepts to help develop the game, believing it would be a first prototype, but Alcorn's success impressed both Bushnell and Dabney, leading them to believe they had a major success on hand and prepared to offer the game to Bally as part of the contract.<ref name="edge"/> |

||

Meanwhile, Bushnell and Dabney had gone to incorporate the firm, but found that [[Syzygy (astronomy)|Syzygy]] (an astronomical term) already existed in California. |

Meanwhile, Bushnell and Dabney had gone to incorporate the firm, but found that [[Syzygy (astronomy)|Syzygy]] (an astronomical term) already existed in California. Bushnell enjoyed the strategy board game ''[[Go (game)|Go]]'', and in considering various terms from the game, they chose to name the company ''[[Atari (go)|atari]]'', a Japanese term {{linktext|当たり}} that in the context of the game means a state where a [[Rules of go#Stones|stone]] or group of stones is imminently in danger of being taken by one's opponent (equivalent to the concept of [[check (chess)|check]] in [[chess]]).<ref name="edge"/> Other terms Bushnell had offer included ''[[List of Go terms#Gote.2C sente and tenuki|sente]]'' (when a Go player has the initiative; Bushnell would use this term years later to name [[Sente Technologies|another company of his]]) and ''[[Hane (Go)|hane]]'' (a ''Go'' move to go around an opponent's pieces).<ref name="rise and fall chp2"/> Atari was incorporated in the state of California on June 27, 1972.<ref name="rise and fall chp2"/><ref name="inc1972">[https://web.archive.org/web/20071016062150/http://kepler.ss.ca.gov/corpdata/ShowAllList?QueryCorpNumber=C0654542 California Secretary of State - California Business Search - Corporation Search Results]</ref> |

||

Bushnell and Dabney offered to license ''Pong'' to both Bally and its Midway subsidiary, but both companies rejected it because it required two players. Instead, Bushnell and Dabney opted to create a test unit themselves and see how it was received at a local establishment.<ref name="edge"/> By August 1972, the first ''Pong'' was completed. It consisted of a black and white television from [[Walgreens]], the special game hardware, and a coin mechanism from a laundromat on the side which featured a milk carton inside to catch coins. It was placed in a [[Sunnyvale, California|Sunnyvale]] tavern by the name of Andy Capp's to test its viability.<ref>[[Retro gamer]] issue 83. In the chair with Allan Alcorn</ref> The test was extremely successful, so the company created twelve more test units, ten which were distributed across other local bars.<ref name="edge"/> They found that the machines were averaging around {{USD|400}} a week each; in several cases, when bar owners reported that the machines were malfunctioning, Alcorn found that it was due to the coin collector had been overflowing with quarters, shorting out the coin slot mechanism.<ref name="edge"/> They reported these numbers to Bally, who still had not decided on taking the license. Bushnell and Dabney realized that they needed to expand on the game but formally needed to get out of their contract with Bally. Bushnell told Bally that they could offer to make another game for them, but only if they rejected ''Pong''; Bally agreed, letting Atari off the hook for the pinball machine design as well.<ref name="edge"/> |

Bushnell and Dabney offered to license ''Pong'' to both Bally and its Midway subsidiary, but both companies rejected it because it required two players. Instead, Bushnell and Dabney opted to create a test unit themselves and see how it was received at a local establishment.<ref name="edge"/> By August 1972, the first ''Pong'' was completed. It consisted of a black and white television from [[Walgreens]], the special game hardware, and a coin mechanism from a laundromat on the side which featured a milk carton inside to catch coins. It was placed in a [[Sunnyvale, California|Sunnyvale]] tavern by the name of Andy Capp's to test its viability.<ref>[[Retro gamer]] issue 83. In the chair with Allan Alcorn</ref> The test was extremely successful, so the company created twelve more test units, ten which were distributed across other local bars.<ref name="edge"/> They found that the machines were averaging around {{USD|400}} a week each; in several cases, when bar owners reported that the machines were malfunctioning, Alcorn found that it was due to the coin collector had been overflowing with quarters, shorting out the coin slot mechanism.<ref name="edge"/> They reported these numbers to Bally, who still had not decided on taking the license. Bushnell and Dabney realized that they needed to expand on the game but formally needed to get out of their contract with Bally. Bushnell told Bally that they could offer to make another game for them, but only if they rejected ''Pong''; Bally agreed, letting Atari off the hook for the pinball machine design as well.<ref name="edge"/> |

||

After talks to release ''Pong'' through Nutting and several other companies broke down, Bushnell and Dabney decided to release Pong on their own,<ref name="computerspace" /> and Atari, Inc. transformed into a coin-op design and production company. Using investments and funds from a coin-operated machine route, they leased a former concert hall and roller rink in [[Santa Clara, California|Santa Clara]] to produce ''Pong'' cabinets on their own with hired help for the production line. Bushnell had also set up arrangements with local coin-op-game distributors to help move units. Atari shipped their first commercial ''Pong'' unit in November 1972. Over 2,500 ''Pong'' cabinets were made in 1973, and by the end of its production in 1974, Atari had made over 8,000 ''Pong'' cabinets.<ref name="rise and fall chp3">{{cite book | title= |

After talks to release ''Pong'' through Nutting and several other companies broke down, Bushnell and Dabney decided to release Pong on their own,<ref name="computerspace" /> and Atari, Inc. transformed into a coin-op design and production company. Using investments and funds from a coin-operated machine route, they leased a former concert hall and roller rink in [[Santa Clara, California|Santa Clara]] to produce ''Pong'' cabinets on their own with hired help for the production line. Bushnell had also set up arrangements with local coin-op-game distributors to help move units. Atari shipped their first commercial ''Pong'' unit in November 1972. Over 2,500 ''Pong'' cabinets were made in 1973, and by the end of its production in 1974, Atari had made over 8,000 ''Pong'' cabinets.<ref name="rise and fall chp3">{{cite book | title= Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari | first= Scott |last= Cohen | date = 1984 | publisher =[[McGraw-Hill]] | isbn =9780070115439| chapter= Chapter 3 | pages=25 }}</ref> |

||

Atari could not produce ''Pong'' cabinets fast enough to meet the new demand, leading to a number of existing companies in the electro-mechanical games industry and new ventures to produce their own versions of ''Pong''.<ref name="down many times"/> [[Ralph H. Baer]], who had patented the concepts behind the Odyssey through his employer [[Sanders Associates]], felt ''Pong'' and these other games infringed on his ideas. [[Magnavox]] filed suit against Atari and others in April 1974 for patent infringement.<ref>{{cite news| title = Magnavox Sues Firms Making Video Games, Charges Infringement| newspaper = The Wall Street Journal| date = 17 April 1974}}</ref> Under legal counsel's advice, Bushnell opted to have Atari settle out of court with Magnavox by June 1976, agreeing to pay {{USD|1,500,000|long=no}} in eight installments for a perpetual license for Baer's patents and to share technical information and grant a license to use the technology found in all current Atari products and any new products announced between June 1, 1976, and June 1, 1977.<ref name="Ultimate-Legal">{{cite book| title = [[Ultimate History of Video Games]]| first = Steven| last = Kent| authorlink = Steven L. Kent| pages = 45–48| chapter = And Then There Was Pong| publisher = Three Rivers Press| isbn = 0-7615-3643-4| year = 2001}}</ref><ref name="atari fun chp5"/> |

Atari could not produce ''Pong'' cabinets fast enough to meet the new demand, leading to a number of existing companies in the electro-mechanical games industry and new ventures to produce their own versions of ''Pong''.<ref name="down many times"/> [[Ralph H. Baer]], who had patented the concepts behind the Odyssey through his employer [[Sanders Associates]], felt ''Pong'' and these other games infringed on his ideas. [[Magnavox]] filed suit against Atari and others in April 1974 for patent infringement.<ref>{{cite news| title = Magnavox Sues Firms Making Video Games, Charges Infringement| newspaper = The Wall Street Journal| date = 17 April 1974}}</ref> Under legal counsel's advice, Bushnell opted to have Atari settle out of court with Magnavox by June 1976, agreeing to pay {{USD|1,500,000|long=no}} in eight installments for a perpetual license for Baer's patents and to share technical information and grant a license to use the technology found in all current Atari products and any new products announced between June 1, 1976, and June 1, 1977.<ref name="Ultimate-Legal">{{cite book| title = [[Ultimate History of Video Games]]| first = Steven| last = Kent| authorlink = Steven L. Kent| pages = 45–48| chapter = And Then There Was Pong| publisher = Three Rivers Press| isbn = 0-7615-3643-4| year = 2001}}</ref><ref name="atari fun chp5"/> |

||

===Early arcade and home games (1973–1976)=== |

===Early arcade and home games (1973–1976)=== |

||

Around 1973, Bushnell began to expand out the company, moving their corporate headquarters to [[Los Gatos, California|Los Gatos]].<ref name="atari fun chp3"/> Bushnell contracted graphic design artist [[George Opperman]], who ran his own design firm, to create a logo for Atari. Opperman has stated that the logo that was selected was based on the letter "A" but considering Atari's success with ''Pong'', created the logo to fit the "A" shape, with two players on opposite sides of a center line. However, some within Atari at this time dispute this, stating that Opperman had provided several different possible designs and this was the one selected by Bushnell and others. The logo first appeared on Atari's arcade game ''[[Space Race (video game)|Space Race]]'' in 1973, and had become known as the "Fuji" due to its resemblance to [[Mount Fuji]]. In 1976, Atari hired Opperman to establish the company's own art and design division.<ref>{{cite book | last = Lapetino | first |

Around 1973, Bushnell began to expand out the company, moving their corporate headquarters to [[Los Gatos, California|Los Gatos]].<ref name="atari fun chp3"/> Bushnell contracted graphic design artist [[George Opperman]], who ran his own design firm, to create a logo for Atari. Opperman has stated that the logo that was selected was based on the letter "A" but considering Atari's success with ''Pong'', created the logo to fit the "A" shape, with two players on opposite sides of a center line. However, some within Atari at this time dispute this, stating that Opperman had provided several different possible designs and this was the one selected by Bushnell and others. The logo first appeared on Atari's arcade game ''[[Space Race (video game)|Space Race]]'' in 1973, and had become known as the "Fuji" due to its resemblance to [[Mount Fuji]]. In 1976, Atari hired Opperman to establish the company's own art and design division.<ref>{{cite book | last = Lapetino | first = Tim | title = Art of Atari | publisher = [[Dynamite Entertainment]] | date = 2016 | isbn = 9781524101060 | pages = 36–37 }}</ref> |

||

From late 1972 to early 1973, a rift in the business relationship between Bushnell and Dabney began to develop, with Dabney feeling he was being pushed to the side by Bushnell while Bushnell saw Dabney as a potential roadblock to his larger plans for Atari.<ref name="atari fun chp3"/> By March 1973, Dabney formally left Atari, selling his portion of the company for {{USD|250,000}}.<ref name="wired">{{cite magazine | url = https://www.wired.com/story/inside-story-of-pong-excerpt/ |

From late 1972 to early 1973, a rift in the business relationship between Bushnell and Dabney began to develop, with Dabney feeling he was being pushed to the side by Bushnell while Bushnell saw Dabney as a potential roadblock to his larger plans for Atari.<ref name="atari fun chp3"/> By March 1973, Dabney formally left Atari, selling his portion of the company for {{USD|250,000}}.<ref name="wired">{{cite magazine | url = https://www.wired.com/story/inside-story-of-pong-excerpt/ | title = The Inside Story of Pong and the Early Days of Atari | first = Leslie | last = Berlin | date = November 11, 2017 | access-date = May 26, 2018 | magazine = [[Wired (magazine)|Wired]] | archive-date = May 27, 2018 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180527120715/https://www.wired.com/story/inside-story-of-pong-excerpt/ | url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="atari fun chp3">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Chapter 3| pages = [https://archive.org/details/atariincbusiness0000gold/page/93 93–96] | chapter-url = https://archive.org/details/atariincbusiness0000gold/page/93 }}</ref><ref name="nytimes">{{cite web | url = https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/obituaries/ted-dabney-dead-atari-pong.html | title = Ted Dabney, a Founder of Atari and a Creator of Pong, Dies at 81 | first = Nellie | last = Bowles | date = May 31, 2018 | access-date = June 1, 2018 | work = [[The New York Times]] | archive-date = November 8, 2019 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191108220548/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/31/obituaries/ted-dabney-dead-atari-pong.html | url-status = live }}</ref> While Dabney would continue to work for Bushnell on other ventures, including [[Chuck E. Cheese|Pizza Time Theaters]], he had a falling out with Bushnell and ultimately left the video game industry.<ref name="edge"/> |

||

In mid-1973, Atari acquired [[Cyan Engineering]], a computer engineering firm founded by Steve Mayer and Larry Emmons, following a consulting contract with Atari. Bushnell established Atari's internal Grass Valley Think Tank at Cyan to promote research & development of new games and products.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

In mid-1973, Atari acquired [[Cyan Engineering]], a computer engineering firm founded by Steve Mayer and Larry Emmons, following a consulting contract with Atari. Bushnell established Atari's internal Grass Valley Think Tank at Cyan to promote research & development of new games and products.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

||

| Line 81: | Line 85: | ||

Atari secretly spawned a "competitor" called [[Kee Games]] in September 1973,<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/glixel/news/lists/ataris-forgotten-arcade-classics-w485407/quadrapong-w485411|title=Atari's Forgotten Arcade Classics|magazine=Rolling Stone|access-date=2017-12-08|archive-date=December 8, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171208101429/http://www.rollingstone.com/glixel/news/lists/ataris-forgotten-arcade-classics-w485407/quadrapong-w485411|url-status=dead}}</ref> headed by Bushnell's next door neighbor Joe Keenan, to circumvent [[pinball]] distributors' insistence on exclusive distribution deals; both Atari and Kee could market (virtually) the same game to different distributors, with each getting an "exclusive" deal.<ref name="rise and fall chp4"/> Kee was further led by Atari employees: Steve Bristow, a developer that worked under Alcorn on arcade games, Bill White, and Gil Williams. While early Kee games were near-copies of Atari's own games, Kee began developing their own titles such as that drew distributor interest to Kee and effectively helping Bushnell to realize the disruption of the exclusive distribution deals.<ref name="rise and fall chp4"/> |

Atari secretly spawned a "competitor" called [[Kee Games]] in September 1973,<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/glixel/news/lists/ataris-forgotten-arcade-classics-w485407/quadrapong-w485411|title=Atari's Forgotten Arcade Classics|magazine=Rolling Stone|access-date=2017-12-08|archive-date=December 8, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171208101429/http://www.rollingstone.com/glixel/news/lists/ataris-forgotten-arcade-classics-w485407/quadrapong-w485411|url-status=dead}}</ref> headed by Bushnell's next door neighbor Joe Keenan, to circumvent [[pinball]] distributors' insistence on exclusive distribution deals; both Atari and Kee could market (virtually) the same game to different distributors, with each getting an "exclusive" deal.<ref name="rise and fall chp4"/> Kee was further led by Atari employees: Steve Bristow, a developer that worked under Alcorn on arcade games, Bill White, and Gil Williams. While early Kee games were near-copies of Atari's own games, Kee began developing their own titles such as that drew distributor interest to Kee and effectively helping Bushnell to realize the disruption of the exclusive distribution deals.<ref name="rise and fall chp4"/> |

||

In 1974, Atari began to see financial struggles and Bushnell was forced to lay off half the staff.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari was facing increased competition from new arcade game producers, many which made [[video game clone|clones]] of ''Pong'' and other Atari games. An accounting mistake caused them to lose money on the release of ''[[Gran Trak 10]]''.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari also tried to open a division in Japan as Atari Japan to sell their games through, but the venture had several roadblocks. In a 2018 interview Alcorn described the situation as "an utter disaster beyond recognition".<ref name=oral>{{cite web|title=Atari's Hard-Partying Origin Story: An Oral History|date=July 19, 2018|url=https://medium.com/s/story/ataris-hard-partying-origin-story-an-oral-history-c438b0ce9440}}</ref> Bushnell said "We didn't realize that Japan was a closed market, and so we were in violation of all kinds of rules and regulations of the Japanese, and they were starting to give us a real bad time."<ref name=oral/> Gordon "fixed all that for us for a huge commission" according to Bushnell.<ref name=oral/> Atari sold Atari Japan to [[Namco]] for {{USD|500,000|long=no}}, through which Namco would be the exclusive distributor of Atari's games in Japan.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Bushnell has claimed that deals arranged by Gordon saved Atari.<ref>{{cite |

In 1974, Atari began to see financial struggles and Bushnell was forced to lay off half the staff.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari was facing increased competition from new arcade game producers, many which made [[video game clone|clones]] of ''Pong'' and other Atari games. An accounting mistake caused them to lose money on the release of ''[[Gran Trak 10]]''.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari also tried to open a division in Japan as Atari Japan to sell their games through, but the venture had several roadblocks. In a 2018 interview Alcorn described the situation as "an utter disaster beyond recognition".<ref name=oral>{{cite web|title=Atari's Hard-Partying Origin Story: An Oral History|date=July 19, 2018|url=https://medium.com/s/story/ataris-hard-partying-origin-story-an-oral-history-c438b0ce9440|access-date=May 1, 2019|archive-date=May 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190501093128/https://medium.com/s/story/ataris-hard-partying-origin-story-an-oral-history-c438b0ce9440|url-status=live}}</ref> Bushnell said "We didn't realize that Japan was a closed market, and so we were in violation of all kinds of rules and regulations of the Japanese, and they were starting to give us a real bad time."<ref name=oral/> Gordon "fixed all that for us for a huge commission" according to Bushnell.<ref name=oral/> Atari sold Atari Japan to [[Namco]] for {{USD|500,000|long=no}}, through which Namco would be the exclusive distributor of Atari's games in Japan.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Bushnell has claimed that deals arranged by Gordon saved Atari.<ref>{{cite news|title=Marin investor bets on an impulse - SFGate|newspaper=Sfgate |date=July 2, 1995|url=https://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Marin-investor-bets-on-an-impulse-3142764.php|access-date=May 1, 2019|archive-date=May 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190501101034/https://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Marin-investor-bets-on-an-impulse-3142764.php|url-status=live |last1=Abate |first1=Tom }}</ref> Gordon further suggested that Atari merge Kee Games into Atari in September 1974, just ahead of the release of ''[[Tank (video game)|Tank]]'' in November 1974. ''Tank'' was a success in the arcade, and Atari was able to reestablish its financial stability by the end of the year.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/><ref name="atari fun intermission pains">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Intermission: Growing Pains }}</ref> In the merger, Joe Keenan was kept on as president of Atari while Bushnell stayed at CEO.<ref name="rise and fall chp4">{{cite book | title= Zap! The Rise and Fall of Atari | first= Scott |last= Cohen | date = 1984 | publisher =[[McGraw-Hill]] | isbn =9780070115439| chapter= Chapter 4 }}</ref> |

||

Having avoided bankruptcy, Atari continued to expand on its arcade game offerings in 1975. The additional financial stability also allowed Atari to pursue new product ideas. One of these was the idea of a home version of ''Pong'', a concept they had first considered as early as 1973. The cost of integrated circuits to support a home version had fallen enough to be suitable for a home console by 1974, and initial design work on console began in earnest in late 1974 by Alcorn, Harold Lee and Bob Brown. Atari struggled to find a distributor for the console but eventually arranged a deal with [[Sears]] to make 150,000 units by the end of 1975 for the holiday season. Atari was able to meet Sears' order with additional {{USD|900,000|long=no}} investments during 1975. The home ''Pong'' console (branded as Sears Tele-Game) was high-demand product that season, and established Atari with a viable home console division in addition to their arcade division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> By 1976, Atari began releasing home ''Pong'' consoles, including ''Pong'' variants, under their own brand name.<ref name="Gamesutra-Pong">{{cite web| url = http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php| title = The History Of Pong: Avoid Missing Game to Start Industry| first = Bill| last = Loguidice| author2 = Matt Barton| website = [[Gamasutra]]| date = 9 January 2009| access-date = 10 January 2009| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090112004852/http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php| archive-date = 12 January 2009| url-status = live| df = dmy-all}}</ref> The success of home ''Pong'' drew a similar range of competitors to this market, including [[Coleco]] with their [[Coleco Telstar series|Telstar series]] of consoles.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

Having avoided bankruptcy, Atari continued to expand on its arcade game offerings in 1975. The additional financial stability also allowed Atari to pursue new product ideas. One of these was the idea of a home version of ''Pong'', a concept they had first considered as early as 1973. The cost of integrated circuits to support a home version had fallen enough to be suitable for a home console by 1974, and initial design work on console began in earnest in late 1974 by Alcorn, Harold Lee and Bob Brown. Atari struggled to find a distributor for the console but eventually arranged a deal with [[Sears]] to make 150,000 units by the end of 1975 for the holiday season. Atari was able to meet Sears' order with additional {{USD|900,000|long=no}} investments during 1975. The home ''Pong'' console (branded as Sears Tele-Game) was high-demand product that season, and established Atari with a viable home console division in addition to their arcade division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> By 1976, Atari began releasing home ''Pong'' consoles, including ''Pong'' variants, under their own brand name.<ref name="Gamesutra-Pong">{{cite web| url = http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php| title = The History Of Pong: Avoid Missing Game to Start Industry| first = Bill| last = Loguidice| author2 = Matt Barton| website = [[Gamasutra]]| date = 9 January 2009| access-date = 10 January 2009| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090112004852/http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3900/the_history_of_pong_avoid_missing_.php| archive-date = 12 January 2009| url-status = live| df = dmy-all}}</ref> The success of home ''Pong'' drew a similar range of competitors to this market, including [[Coleco]] with their [[Coleco Telstar series|Telstar series]] of consoles.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

||

[[File:Atari-2600-Wood-4Sw-Set.jpg|right|thumb|The third version of the Atari [[Atari 2600|Video Computer System]] sold from 1980 to 1982]] |

[[File:Atari-2600-Wood-4Sw-Set.jpg|right|thumb|The third version of the Atari [[Atari 2600|Video Computer System]] sold from 1980 to 1982]] |

||

In 1975, Bushnell started an effort to produce a flexible video game console that was capable of playing all four of Atari's then-current games. Bushnell was concerned that arcade games took about {{US$|250,000|long=no}} to develop and had about a 10% chance of being successful. Similarly, dedicated home consoles had cost about {{USD|100,000|long=no}} to design but with increased competition, had a limited practical shelf-life of a few months. Instead, a programmable console with swappable games would be far more lucrative.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Development took place at Cyan Engineering, which initially had serious difficulties trying to produce such a machine. However, in early 1976, [[MOS Technology]] released the first inexpensive microprocessor, the [[MOS Technology 6502|6502]], which had sufficient performance for Atari's needs.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari hired [[Joseph C. Decuir|Joe Decuir]] and [[Jay Miner]] to develop the hardware and custom [[Television Interface Adaptor]] for this new console.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Their project, under the codename of "Stella", would become the [[Atari Video Computer System]] (Atari VCS). |

In 1975, Bushnell started an effort to produce a flexible video game console that was capable of playing all four of Atari's then-current games. Bushnell was concerned that arcade games took about {{US$|250,000|long=no}} to develop and had about a 10% chance of being successful. Similarly, dedicated home consoles had cost about {{USD|100,000|long=no}} to design but with increased competition, had a limited practical shelf-life of a few months. Instead, a programmable console with swappable games would be far more lucrative.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Development took place at [[Cyan Engineering]], which initially had serious difficulties trying to produce such a machine. However, in early 1976, [[MOS Technology]] released the first inexpensive microprocessor, the [[MOS Technology 6502|6502]], which had sufficient performance for Atari's needs.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Atari hired [[Joseph C. Decuir|Joe Decuir]] and [[Jay Miner]] to develop the hardware and custom [[Television Interface Adaptor]] for this new console.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Their project, under the codename of "Stella", would become the [[Atari Video Computer System]] (Atari VCS). |

||

===Workplace culture=== |

===Workplace culture=== |

||

Atari, as a private company under Bushnell, gained a reputation for relaxed employee policies in areas such as formal hours and dress codes, and company-sponsored recreational activities involving alcohol, [[marijuana]], and hot tubs.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Board and management meetings to discuss new ideas moved from formal events at hotel meeting rooms to more casual gatherings at Bushnell's home, Cyan Engineering, and a coastal resort in [[Pajaro Dunes, California|Pajaro Dunes]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/><ref name="inc bushnell 1984"/> Dress codes were considered atypical for a professional setting, with most working in jeans and tee shirts.<ref name="inc bushnell 1984"/> Many of the workers hired early on to construct games were [[hippie]]s who knew enough to help to solder components together and took minimal wages.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Several former employees, speaking in years that followed, described this as the common culture of the 1970s and not unique to Atari.<ref name="kotaku female atari">{{Cite web | url = https://kotaku.com/sex-pong-and-pioneers-what-atari-was-really-like-ac-1822930057 | title = Sex, Pong, And Pioneers: What Atari Was Really Like, According To Women Who Were There | first = Cecilia | last = D'Anastasio | date = February 12, 2018 | access-date = February 12, 2018 | work = [[Kotaku]] }}</ref><ref name="polygon gdc">{{cite web | url = https://www.polygon.com/2018/1/31/16955152/nolan-bushnell-gdc-pioneer-award-notnolan-metoo | title = GDC cancels achievement award for Atari founder after outcry | first= |

Atari, as a private company under Bushnell, gained a reputation for relaxed employee policies in areas such as formal hours and dress codes, and company-sponsored recreational activities involving alcohol, [[marijuana]], and hot tubs.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Board and management meetings to discuss new ideas moved from formal events at hotel meeting rooms to more casual gatherings at Bushnell's home, Cyan Engineering, and a coastal resort in [[Pajaro Dunes, California|Pajaro Dunes]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/><ref name="inc bushnell 1984"/> Dress codes were considered atypical for a professional setting, with most working in jeans and tee shirts.<ref name="inc bushnell 1984"/> Many of the workers hired early on to construct games were [[hippie]]s who knew enough to help to solder components together and took minimal wages.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Several former employees, speaking in years that followed, described this as the common culture of the 1970s and not unique to Atari.<ref name="kotaku female atari">{{Cite web | url = https://kotaku.com/sex-pong-and-pioneers-what-atari-was-really-like-ac-1822930057 | title = Sex, Pong, And Pioneers: What Atari Was Really Like, According To Women Who Were There | first = Cecilia | last = D'Anastasio | date = February 12, 2018 | access-date = February 12, 2018 | work = [[Kotaku]] | archive-date = February 12, 2018 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180212212019/https://kotaku.com/sex-pong-and-pioneers-what-atari-was-really-like-ac-1822930057 | url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="polygon gdc">{{cite web | url = https://www.polygon.com/2018/1/31/16955152/nolan-bushnell-gdc-pioneer-award-notnolan-metoo | title = GDC cancels achievement award for Atari founder after outcry | first = Owen | last = Good | date = January 31, 2018 | accessdate = April 8, 2021 | work = [[Polygon (website)|Polygon]] | archive-date = March 10, 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210310120808/https://www.polygon.com/2018/1/31/16955152/nolan-bushnell-gdc-pioneer-award-notnolan-metoo | url-status = live }}</ref> |

||

This approach changed in 1978 after [[Ray Kassar]] was brought on from Warner initially to help with marketing but eventually took on a larger role in the company, displacing Bushnell and Keenan, and instituting more formal employee policies for the company.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

This approach changed in 1978 after [[Ray Kassar]] was brought on from Warner initially to help with marketing but eventually took on a larger role in the company, displacing Bushnell and Keenan, and instituting more formal employee policies for the company.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

||

| Line 95: | Line 99: | ||

==As a subsidiary of Warner Communications== |

==As a subsidiary of Warner Communications== |

||

===Under Nolan Bushnell (1976–1978)=== |

===Under Nolan Bushnell (1976–1978)=== |

||

Ahead of entering the home console market, Atari recognized they needed additional capital to support this market, and though they had acquired smaller investments through 1975, they needed a larger infusion of funds.<ref name="atari fun chp5"/> Bushnell had considered [[public company|going public]], then tried to sell the company to [[MCA Inc.|MCA]] and [[Disney]] but they passed. Instead, after at least six months of negotiations in 1976, Atari took an acquisition offer from [[Warner Communications]] for {{USD|28 million|long=no}} that was completed in November 1976, of which Bushnell received {{USD|15 million|long=no}}. Bushnell was kept as chairman and CEO while Keenan was retained as president.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/><ref name="NGen4">{{cite journal|title=What the Hell has Nolan Bushnell Started? |journal=[[Next Generation (magazine)|Next Generation]]|issue=4|publisher=[[Imagine Media]]|date=April 1995|pages=6–11}}</ref> |

Ahead of entering the home console market, Atari recognized they needed additional capital to support this market, and though they had acquired smaller investments through 1975, they needed a larger infusion of funds.<ref name="atari fun chp5"/> Bushnell had considered [[public company|going public]], then tried to sell the company to [[MCA Inc.|MCA]] and [[Disney]] but they passed. Instead, after at least six months of negotiations in 1976, Atari took an acquisition offer from [[Warner Communications]] for {{USD|28 million|long=no}} that was completed in November 1976, of which Bushnell received {{USD|15 million|long=no}}. Bushnell was kept as chairman and CEO while Keenan was retained as president.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/><ref name="NGen4">{{cite journal|title=What the Hell has Nolan Bushnell Started? |journal=[[Next Generation (magazine)|Next Generation]]|issue=4|publisher=[[Imagine Media]]|date=April 1995|pages=6–11}}</ref> Atari had about $40 million in annual revenue;{{r|libes198205}} for Warner, the deal represented an opportunity to buoy its underperforming film and music business divisions.<ref name="inc bushnell 1984">{{cite magazine | url = https://www.inc.com/magazine/19841001/136.html | title = When The Magic Goes | first = Steve | last = Goll | date = October 1, 1984 | accessdate = April 2, 2021 | magazine = [[Inc. (magazine)|Inc.]] | archive-date = March 10, 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210310075000/http://www.inc.com/magazine/19841001/136.html | url-status = live }}</ref> Along with Warner's purchase, Atari had established its new headquarters in the Moffett Park area in [[Sunnyvale, California]].<ref name="atari fun chp5">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Chapter 5 }}</ref> |

||

[[File:Atarivideomusic.png|thumb|right|Atari Video Music]] |

[[File:Atarivideomusic.png|thumb|right|Atari Video Music]] |

||

During Atari's negotiations with Warner, [[Fairchild Camera and Instrument]] announced the [[Fairchild Channel F]]. The Channel F was the first programmable home console that used cartridges to play different games.<ref name="fc fairchild carts">{{cite web | url = https://www.fastcompany.com/3040889/the-untold-story-of-the-invention-of-the-game-cartridge | title = The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge | first |

During Atari's negotiations with Warner, [[Fairchild Camera and Instrument]] announced the [[Fairchild Channel F]]. The Channel F was the first programmable home console that used cartridges to play different games.<ref name="fc fairchild carts">{{cite web | url = https://www.fastcompany.com/3040889/the-untold-story-of-the-invention-of-the-game-cartridge | title = The Untold Story Of The Invention Of The Game Cartridge | first = Benj | last = Edwards | date = January 22, 2015 | accessdate = April 9, 2021 | work = [[Fast Company]] | archive-date = January 11, 2020 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200111161144/https://www.fastcompany.com/3040889/the-untold-story-of-the-invention-of-the-game-cartridge | url-status = live }}</ref> Following Warner's acquisition, they provided {{USD|120 million|long=no}} into Stella's development, allowing Atari to complete the console by early 1977.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Its announcement on June 4, 1977, may have been delayed until after June 1, 1977, to wait out the terms of the Magnavox settlement from the earlier ''Pong'' patent lawsuit so they would not have to disclose information on it.<ref name="atari fun chp5"/> The Atari VCS was released in September 1977.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Most of the [[launch title]]s for the console were games based on Atari's successful arcade games, such as ''[[Combat (video game)|Combat]]'' that incorporated elements of both ''Tank'' and ''[[Jet Fighter (video game)|Jet Fighter]]''.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> The company made around 400,000 Atari VCS units for the 1977 holiday season, most which were sold but the company had lost around {{USD|25 million|long=no}} due to production problems that caused some units to be delivered late to retailers.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2">{{cite web | url = https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3766/atari_the_golden_years__a_.php?print=1 | title = Atari: The Golden Years -- A History, 1978-1981 | first = Steve | last = Fulton | date = August 21, 2008 | accessdate = April 6, 2021 | work = [[Gamasutra]] | archive-date = September 17, 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210917215026/https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/3766/atari_the_golden_years__a_.php?print=1 | url-status = live }}</ref> |

||

In addition to the VCS, Atari continued to manufacture dedicated home console units through 1977 though discontinued these by 1978 and destroyed their unsold stock.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Another one-off device from the consumer products division released in 1977 was [[Atari Video Music]], a computerized device that |

In addition to the VCS, Atari continued to manufacture dedicated home console units through 1977 though discontinued these by 1978 and destroyed their unsold stock.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> Another one-off device from the consumer products division released in 1977 was [[Atari Video Music]], a computerized device that takes an audio input and creates graphics displays to a monitor. The unit did not sell well and was discontinued in 1978.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

||

Atari continued its arcade game line as it built up its consumer division. ''[[Breakout (video game)|Breakout]]'' in 1976 was one of Atari's last games based on [[transistor–transistor logic]] (TTL) discrete logic design before the company transitioned to [[microprocessor]]s. It was engineered by [[Steve Wozniak]] based on Bushnell's concept of a single-player ''Pong'', and using as few TTL chips as possible from an informal challenge given to Wozniak by |

Atari continued its arcade game line as it built up its consumer division. ''[[Breakout (video game)|Breakout]]'' in 1976 was one of Atari's last games based on [[transistor–transistor logic]] (TTL) discrete logic design before the company transitioned to [[microprocessor]]s. It was engineered by [[Steve Wozniak]] based on Bushnell's concept of a single-player ''Pong'', and using as few TTL chips as possible from an informal challenge given to Wozniak by Atari employee [[Steve Jobs]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari">{{cite web | url = http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/130414/the_history_of_atari_19711977.php?print=1 | title = The History of Atari: 1971-1977 | first = Steve | last = Fulton | date = November 6, 2007 | access-date = September 11, 2018 | work = [[Gamasutra]] | archive-date = September 12, 2018 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180912021902/http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/130414/the_history_of_atari_19711977.php?print=1 | url-status = live }}</ref> ''Breakout'' was successful, selling around 11,000 units, and Atari still struggled to meet demand. Atari exported a limited number of units to Namco via its prior Atari Japan venture, and led Namco to create its own clone of the game to meet demand in Japan, and helped to establish Namco as a major company in the Japanese video game industry. Subsequently, Atari moved to microprocessors for its arcade games such as ''Cops ‘N Robbers'', ''[[Sprint 2]]'', ''Tank 8'', and ''[[Night Driver (video game)|Night Driver]]''.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

||

[[File:Chuck E Cheese's - 13907585523 01.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Chuck E. Cheese]] franchise was first developed by Bushnell at Atari in 1977.]] |

[[File:Chuck E Cheese's - 13907585523 01.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Chuck E. Cheese]] franchise was first developed by Bushnell at Atari in 1977.]] |

||

Alongside continuing work in arcade game development and their preparations to launch the Atari VCS, Atari launched two more products in 1977. The first was their Atari Pinball division, which included [[Steve Ritchie (pinball designer)|Steve Ritchie]] and [[Eugene Jarvis]].<ref name="atari fun intermission pinball">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Intermission: Balls of Steel }}</ref> Around 1976, Atari had been concerned that arcade operators were getting nervous on the prospects of future arcade games, and thus launched their own pinball machines to accompany their arcade games. Atari's pinball machines were built following the technology principles they had learned from arcade and home console games, using [[solid-state electronics]] over electro-mechanical components to make them easier to design and repair. The division released about ten different pinball units between 1977 and 1979. Many of the machines were considered to be innovative for their time but were difficult to produce and meet distributors' demand.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> The second new venture in 1977 was the first of the [[Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatre|Pizza Time Theatre]] (later known as Chuck E. Cheese), based on the pizza arcade concept that Bushnell had from the start. At this stage, the concept also allowed Atari to bypass problems with getting their arcade games placed into arcades by effectively controlling the arcade itself, while also creating a family-friendly environment. The first restaurant/arcade launched in [[San Jose, California]] in May 1977.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

Alongside continuing work in arcade game development and their preparations to launch the Atari VCS, Atari launched two more products in 1977. The first was their Atari Pinball division, which included [[Steve Ritchie (pinball designer)|Steve Ritchie]] and [[Eugene Jarvis]].<ref name="atari fun intermission pinball">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Intermission: Balls of Steel }}</ref> Around 1976, Atari had been concerned that arcade operators were getting nervous on the prospects of future arcade games, and thus launched their own pinball machines to accompany their arcade games. Atari's pinball machines were built following the technology principles they had learned from arcade and home console games, using [[solid-state electronics]] over electro-mechanical components to make them easier to design and repair. The division released about ten different pinball units between 1977 and 1979. Many of the machines were considered to be innovative for their time but were difficult to produce and meet distributors' demand.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> The second new venture in 1977 was the first of the [[Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatre|Pizza Time Theatre]] (later known as Chuck E. Cheese), based on the pizza arcade concept that Bushnell had from the start. At this stage, the concept also allowed Atari to bypass problems with getting their arcade games placed into arcades by effectively controlling the arcade itself, while also creating a family-friendly environment. The first restaurant/arcade launched in [[San Jose, California]], in May 1977.<ref name="gamasutra history atari"/> |

||

Atari hired in more programmers after releasing the VCS to start a second wave of games for release in 1978. In contrast to the launch titles that were inspired by Atari's arcade games, the second batch of games released in 1978 were more novel ideas including some based on board games, and were more difficult to sell.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Warner's Manny Gerard, who oversaw Atari, brought in [[Ray Kassar]], formerly a vice president at [[Burlington Industries]], to help market Atari's products. Kassar was hired in February 1978 as president of the Atari consumer division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Kassar helped to develop a commercialization strategy for these games through 1978, and oversaw the creation of a new marketing campaign featuring multiple celebrities unified under the slogan "Don't Watch TV Tonight, Play It", and bringing in celebrities to help advertise these games. Kassar also instituted programs to increase production of the VCS and improve [[quality assurance]] of the console and games. As they approached the end of 1978, Atari had prepared 800,000 VCS units, but sales were languishing ahead of the holiday sales period.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

Atari hired in more programmers after releasing the VCS to start a second wave of games for release in 1978. In contrast to the launch titles that were inspired by Atari's arcade games, the second batch of games released in 1978 were more novel ideas including some based on board games, and were more difficult to sell.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Warner's Manny Gerard, who oversaw Atari, brought in [[Ray Kassar]], formerly a vice president at [[Burlington Industries]], to help market Atari's products. Kassar was hired in February 1978 as president of the Atari consumer division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Kassar helped to develop a commercialization strategy for these games through 1978, and oversaw the creation of a new marketing campaign featuring multiple celebrities unified under the slogan "Don't Watch TV Tonight, Play It", and bringing in celebrities to help advertise these games. Kassar also instituted programs to increase production of the VCS and improve [[quality assurance]] of the console and games. As they approached the end of 1978, Atari had prepared 800,000 VCS units, but sales were languishing ahead of the holiday sales period.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

||

Kassar's influence on Atari grew throughout 1978, leading to conflict between Bushnell and Warner Communications. Among other concerns about the direction Kassar was taking the company, Bushnell cautioned Warner that they needed to continue to innovate on the home console and could not simply release games for the VCS indefinitely like a music business.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> In a November 1978 meeting with Warner Communications, Bushnell said to Gerard that they had produced far too many VCS units to be sold that season and Atari's consumer division would suffer a major loss. However, Kassar's marketing plan, alongside the influence of the arcade hit ''[[Space Invaders]]'' from [[Taito]], led to a large surge in VCS sales, and Atari's consumer division ended the year with {{USD|200 million|long=no}} in sales.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

Kassar's influence on Atari grew throughout 1978, leading to conflict between Bushnell and Warner Communications. Among other concerns about the direction Kassar was taking the company, Bushnell cautioned Warner that they needed to continue to innovate on the home console and could not simply release games for the VCS indefinitely like a music business.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> In a November 1978 meeting with Warner Communications, Bushnell said to Gerard that they had produced far too many VCS units to be sold that season and Atari's consumer division would suffer a major loss. However, Kassar's marketing plan, alongside the influence of the arcade hit ''[[Space Invaders]]'' from [[Taito]], led to a large surge in VCS sales, and Atari's consumer division ended the year with {{USD|200 million|long=no}} in sales.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Warner removed Bushnell as chairman and co-CEO of the company, but offered to let him stay on as a director and creative consultant. Bushnell refused and left the company. Bushnell purchased the rights for Pizza Time Theatre for {{USD|500,000|long=no}} from Warner before leaving.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Keenan was moved to Atari's chairman and Kassar assigned as president after Bushnell's departure; Keenan left the company a few months later to join Bushnell in managing Pizza Time Theatre, and Kassar was promoted to CEO and chairman of Atari.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/><ref name="atari fun chp7">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Chapter 7 }}</ref> |

||

===Under Ray Kassar ( |

=== Under Ray Kassar (1979–1982) === |

||

With Bushnell's departure, Kassar implemented significant changes in the workplace culture in early 1979 to make it more professional, and cancelled several of the engineering programs that Bushnell had established. Kassar also had expressed some frustration with the programmers at Atari, and was known to have called them "spoiled brats" and "prima donnas" at times.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

With Bushnell's departure, Kassar implemented significant changes in the workplace culture in early 1979 to make it more professional, and cancelled several of the engineering programs that Bushnell had established. Kassar also had expressed some frustration with the programmers at Atari, and was known to have called them "spoiled brats" and "prima donnas" at times.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

||

The changes in management style led to rising tensions from the game developers at Atari who had been used to freedom in developing their titles. One example was ''[[Superman (Atari 2600)|Superman]]'' in 1979, one of the first movie tie-ins that had been sought by Warner to accompany the release of [[Superman (1978 film)|the 1978 film]]. Warner, through Kassar, had pressured [[Warren Robinett]] to convert his game-in-progress ''[[Adventure (1980 video game)|Adventure]]'' from a generic adventure game to the ''Superman''-themed title. Robinett refused, but did help fellow programmer [[John Dunn (software developer)|John Dunn]] to make the conversion after he volunteered.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Further, after Warner refused to include programmer credits into game manuals over concern that competitors may try to hire them away, Robinett secretly stuck his name into ''Adventure'' in one of the first known [[Easter egg (media)|Easter eggs]] as to bypass this issue.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> The transition from Bushnell to Kassar led to a large number of departures from the company over the next few years.<ref name="atari fun chp7"/> Four of Atari's programmers—David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Larry Kaplan, and Alan Miller—whose games had contributed collectively to over 60% of the company's game sales in 1978, left Atari in mid-1979 after requesting and being denied additional compensation for their performance, and formed [[Activision]] in October of that year to make their own Atari VCS games based on their knowledge of the console.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Similarly, [[Rob Fulop]], who programmed the arcade conversion of ''[[Missile Command]]'' for the VCS in 1981 that sold over 2.5 million units, received only a minimal bonus that year, and left with other disgruntled Atari programmers to form [[Imagic]] in 1981.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

The changes in management style led to rising tensions from the game developers at Atari who had been used to freedom in developing their titles. One example was ''[[Superman (Atari 2600)|Superman]]'' in 1979, one of the first movie tie-ins that had been sought by Warner to accompany the release of [[Superman (1978 film)|the 1978 film]]. Warner, through Kassar, had pressured [[Warren Robinett]] to convert his game-in-progress ''[[Adventure (1980 video game)|Adventure]]'' from a generic adventure game to the ''Superman''-themed title. Robinett refused, but did help fellow programmer [[John Dunn (software developer)|John Dunn]] to make the conversion after he volunteered.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Further, after Warner refused to include programmer credits into game manuals over concern that competitors may try to hire them away, Robinett secretly stuck his name into ''Adventure'' in one of the first known [[Easter egg (media)|Easter eggs]] as to bypass this issue.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> The transition from Bushnell to Kassar led to a large number of departures from the company over the next few years.<ref name="atari fun chp7"/> Four of Atari's programmers—David Crane, Bob Whitehead, Larry Kaplan, and Alan Miller—whose games had contributed collectively to over 60% of the company's game sales in 1978, left Atari in mid-1979 after requesting and being denied additional compensation for their performance, and formed [[Activision]] in October of that year to make their own Atari VCS games based on their knowledge of the console.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Similarly, [[Rob Fulop]], who programmed the arcade conversion of ''[[Missile Command]]'' for the VCS in 1981 that sold over 2.5 million units, received only a minimal bonus that year, and left with other disgruntled Atari programmers to form [[Imagic]] in 1981.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

||

Beginning in 1979, the Atari coin-operated games division started releasing cabinets incorporating [[vector graphics]] displays after the success of the Cinematronics game [[Space Wars]] in 1977–78. Their first vector graphics game, ''[[Lunar Lander (1979 video game)|Lunar Lander]]'', was a modest success, but their second arcade title, ''[[Asteroids (video game)|Asteroids]]'', was highly popular, displacing ''Space Invaders'' as the most popular game in the United States.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Atari produced over 70,000 ''Asteroids'' cabinets, and made an estimated {{USD|150 million|long=no}} from sales.<ref>{{cite magazine |magazine=[[Retro Gamer]] |issue=68 |publisher=[[Imagine Publishing]] |year=2009 |url=http://www.rawbw.com/~delman/pdf/making_of_Asteroids.pdf |title=The Making of Asteroids |access-date=December 18, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131219041721/http://www.rawbw.com/~delman/pdf/making_of_Asteroids.pdf |archive-date=December 19, 2013 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> ''Asteroids'' along with ''Space Invaders'' helped to usher in the [[golden age of arcade video games]] that lasted until around 1983; Atari contributed several more games that were considered part of this golden age, including ''[[Missile Command]]'', ''[[Centipede (video game)|Centipede]]'', and ''[[Tempest (video game)|Tempest]]''.<ref>{{cite book| last = Kent| first = Steven L.| author-link = Steven L. Kent| title = The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon| publisher = [[Three Rivers Press]]| year = 2001| isbn = 0-7615-3643-4 }}</ref><ref name="verge history">{{cite web | url = https://www.theverge.com/2013/1/16/3740422/the-life-and-death-of-the-american-arcade-for-amusement-only | title = For Amusement Only: the life and death of the American arcade | first= Laura | last = June | date = January 16, 2013 | access-date = August 13, 2020 | work = [[The Verge]] }}</ref> |

Beginning in 1979, the Atari coin-operated games division started releasing cabinets incorporating [[vector graphics]] displays after the success of the Cinematronics game [[Space Wars]] in 1977–78. Their first vector graphics game, ''[[Lunar Lander (1979 video game)|Lunar Lander]]'', was a modest success, but their second arcade title, ''[[Asteroids (video game)|Asteroids]]'', was highly popular, displacing ''Space Invaders'' as the most popular game in the United States.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Atari produced over 70,000 ''Asteroids'' cabinets, and made an estimated {{USD|150 million|long=no}} from sales.<ref>{{cite magazine |magazine=[[Retro Gamer]] |issue=68 |publisher=[[Imagine Publishing]] |year=2009 |url=http://www.rawbw.com/~delman/pdf/making_of_Asteroids.pdf |title=The Making of Asteroids |access-date=December 18, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131219041721/http://www.rawbw.com/~delman/pdf/making_of_Asteroids.pdf |archive-date=December 19, 2013 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> ''Asteroids'' along with ''Space Invaders'' helped to usher in the [[golden age of arcade video games]] that lasted until around 1983; Atari contributed several more games that were considered part of this golden age, including ''[[Missile Command]]'', ''[[Centipede (video game)|Centipede]]'', and ''[[Tempest (video game)|Tempest]]''.<ref>{{cite book| last = Kent| first = Steven L.| author-link = Steven L. Kent| title = The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon| publisher = [[Three Rivers Press]]| year = 2001| isbn = 0-7615-3643-4 }}</ref><ref name="verge history">{{cite web | url = https://www.theverge.com/2013/1/16/3740422/the-life-and-death-of-the-american-arcade-for-amusement-only | title = For Amusement Only: the life and death of the American arcade | first = Laura | last = June | date = January 16, 2013 | access-date = August 13, 2020 | work = [[The Verge]] | archive-date = October 6, 2014 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20141006081005/http://www.theverge.com/2013/1/16/3740422/the-life-and-death-of-the-american-arcade-for-amusement-only | url-status = live }}</ref> |

||

[[File:Atari-400-Comp.jpg|thumb|The [[Atari 400]] was released in 1979.]] |

[[File:Atari-400-Comp.jpg|thumb|The [[Atari 400]] was released in 1979.]] |

||

A project to design a successor to the VCS started as soon as the system shipped in mid-1977. The original development team, including Meyer, Miner and Decuir, estimated the VCS had a lifespan of about three years, and decided to build the most powerful machine they could given that time frame. They set a goal to be able to support 1978-vintage arcade games, as well as features of the upcoming [[personal computer]] such as the [[Apple II]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> The project resulted in the first home computers from Atari, the [[Atari 8-bit |

A project to design a successor to the VCS started as soon as the system shipped in mid-1977. The original development team, including Meyer, Miner and Decuir, estimated the VCS had a lifespan of about three years, and decided to build the most powerful machine they could given that time frame. They set a goal to be able to support 1978-vintage arcade games, as well as features of the upcoming [[personal computer]] such as the [[Apple II]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> The project resulted in the first home computers from Atari, the [[Atari 8-bit computers|Atari 800 and Atari 400]], both launched in 1979. These computer systems were mostly [[Proprietary software|closed systems]], and most of the initial games were developed by Atari, drawing from programmers from the VCS line.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Sales into early 1980 were poor and there was little to distinguish the computer line from the current console products. In March 1980, the company released ''[[Star Raiders]]'', a space combat game developed by [[Doug Neubauer]] based on ''[[Star Trek (1971 video game)|Star Trek]]'' game that had been popular on mainframe computers. ''Star Raiders'' became the Atari 400/800 system seller, but quickly emphasized the lack of software for the computers due to the system's closed nature and the limited rate that Atari's programmers could produce titles.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Third-party programmers found means to get technical information about the computer specifications either directly from Atari employees or from [[reverse engineering]], and by late 1980, third-party applications and games began to emerge for the 8-bit computer family, and the specialized magazine ''[[ANALOG Computing]]'' was established for Atari computer programmers to share programming information. While Atari did not formally release development information, they supported this external community by launching the [[Atari Program Exchange]] (APX) in 1981, a mail-order service that programmers could offer their applications and games to other users of Atari's 8-bit computers.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> By this point, Atari's computers were facing new competition from the [[VIC-20]].<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> |

||

A short-lived Atari Electronics division was created to make [[electronic game]]s that ran from 1979 to 1981. They successfully released one product, a handheld version of Atari's arcade ''[[Touch Me (arcade game)|Touch Me]]'' game, which played similar to ''[[Simon (game)|Simon]]'', in 1979. The division began work on ''Cosmos'', a system that was to combine LED lights and a holographic screen. Atari had promoted the game at the 1981 CES, but following Alcorn's departure in 1981, opted not to follow through on making it and closed down the Electronics division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/><ref name="atari fun intermission">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Intermission: Back to Our Grass Roots }}</ref> |

A short-lived Atari Electronics division was created to make [[electronic game]]s that ran from 1979 to 1981. They successfully released one product, a handheld version of Atari's arcade ''[[Touch Me (arcade game)|Touch Me]]'' game, which played similar to ''[[Simon (game)|Simon]]'', in 1979. The division began work on ''Cosmos'', a system that was to combine LED lights and a holographic screen. Atari had promoted the game at the 1981 CES, but following Alcorn's departure in 1981, opted not to follow through on making it and closed down the Electronics division.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/><ref name="atari fun intermission">{{cite book | title = Atari Inc: Business is Fun | first1 = Marty | last1 = Goldberg | first2 = Curt | last2 = Vendel | year = 2012 | isbn = 978-0985597405 | publisher = Sygyzy Press | chapter=Intermission: Back to Our Grass Roots }}</ref> |

||

| Line 127: | Line 131: | ||

Until 1980, the Atari VCS was the only major programmable console on the market and Atari the only supplier for its games, but that year is when Atari began to experience its first major competition as [[Mattel Electronics]] brought the [[Intellivision]] to market.<ref name="down many times"/> Activision also released its first set of third-party games for the Atari VCS.<ref name="gamasutra history atari 2"/> Atari took action against Activision starting 1980, first by trying to tarnish the company's reputation, then by taking legal action accusing the four programmers of stealing trade secrets and violating [[non-disclosure agreement]]s. This lawsuit was eventually settled out of court in 1982, with Activision agreeing to pay a small license fee to Atari for every game sold. This effectively validated Activision's development model and made them the first [[third-party developer]] in the industry.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1537/the_history_of_activision.php?print=1 |title=The History Of Activision |work=Gamasutra |first=Jeffrey |last=Flemming |access-date=December 30, 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220122651/http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/1537/the_history_of_activision.php?print=1 |archive-date=December 20, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0202/052.html#788254c31a16 |title=Activision's Unlikely Hero |first=Peter |last=Beller |date=January 15, 2009 |access-date=February 12, 2019 |work=[[Forbes (magazine)|Forbes]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170806105646/https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0202/052.html#788254c31a16 |archive-date=August 6, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> |